行动与反抗

——挪威建筑师的成就

2017-07-12汉斯斯科特英格里德赫尔辛阿尔莫斯HansSkotteIngeridHelsingAlmaas

汉斯·斯科特,英格里德·赫尔辛·阿尔莫斯/Hans Skotte, Ingerid Helsing Almaas

司马蕾 译/Translated by SIMA Lei

行动与反抗

——挪威建筑师的成就

汉斯·斯科特,英格里德·赫尔辛·阿尔莫斯/Hans Skotte, Ingerid Helsing Almaas

司马蕾 译/Translated by SIMA Lei

建筑师的工作往往与占主导地位的权力结构相关,或在某些社会中与政治相关。在挪威,建筑职业从第二次世界大战以来就与政治发展密切相关,尤其在住宅领域的重建工作中。在住宅建造经济下的城市发展日益偏向技术治国主义化,而1960和1970年代出现了强烈的反抗,无论是公众还是职业建筑师都开始聚焦于环保观念。在城市中心之外,国家政策致力于支持区域经济的发展,在现代福利国家进程中,建筑师在塑造小型社区的实体环境中起到关键作用。而今,建筑职业受到的外界影响日渐减小,很多充满创造才能的挪威建筑师将他们的工作变成影响挪威本土以及全球的资源和灵感。

挪威,战后重建,住宅政策,技术治国主义,保护,政策福利,性别平等,北欧模式

建筑是一项具有社会性的工作,因此,建筑师的工作势必与其所在社会的社会和经济事件发生联系。汉斯·斯科特和英格里德·赫尔辛·阿尔莫斯认为,在20世纪下半叶的挪威,这种联系表现得尤为紧密。虽然建筑行业的政治影响力在各个时代有盛衰波动,但那些有才能的建筑师们取得的成就却能跨越时空,给身处各个时代的人们带来灵感。

建筑师的工作总是与他们所处的社会中普遍存在的权力结构或政治息息相关。因此,建筑实际上反映了那些有能力雇用建筑师的人心中的愿望和象征。从金字塔、帕提农神庙到帕拉迪奥和普金的作品莫不体现着这种映射。当西方文化输出到世界其他地方时,建筑也成为了殖民政策的一部分;而当这些殖民地在300年之后开始为自由斗争时,建筑也是彰显其独立性的重要标志。进入20世纪后,现代主义建筑则展现出新形式的国家的愿景。即使在今天,对于诸如“归零地”一类的建筑,我们除了将其看作高度政治化的象征,又能如何理解它呢?

然而,建筑也不仅仅是出自训练有素的建筑师的产物。基于比较合理的估计,我们可以认为全球仅有约5%的建筑环境是由受过训练的建筑师设计的。其余的建筑要么是由工程师主导建造的,要么就是由当地人自行修建的。不过在挪威,建筑师在塑造现代化的建筑环境方面比在大多数国家更有主导权——至少直到最近都是如此。这主要是因为挪威的经济发达,经济力量给予了我们不断扩大和翻新建筑物的能力,这一不停更替的过程也和我们历史上喜爱使用寿命较短的木材来建造建筑的传统有关。这种建筑环境与形成它的政治力量之间的互惠性在所有的社会中都可以见到,但即便如此,建筑师和建筑物在现代挪威的发展中也可能比在其他许多国家发挥着更重要的政治作用。挪威(图1)人口稀少,在1950年代初期仅有约300万人(今天则上升到了约520万人),这些人口分布在相当于内蒙古的2/3规模的约325,000km2的土地上。因此,即使在20世纪,无论用哪种标准看,建筑在挪威都是个很小的行业,其卓越的影响力主要源于建筑师们在二次大战后的岁月中承担的专业承诺和社会责任。

战后重建

要理解今天的故事和昨天的历史间的关系,我们需要先了解一些战前的社会线索。挪威在历史上没有过封建制度或贵族王朝来建造国家性的建筑或宫殿。战前的挪威拥有的是基于渔业的强大的沿海经济(图2),并实行着包含着内在不平等性的传统土地所有制度。在经历了19世纪的工业化之后,劳工运动成为了一个重要的政治力量,到1930年代,这一力量已经成为了挪威政界的主宰。许多建筑师也加入了这一运动,他们的参与大多是出于信仰,而不是出于阶级原因。他们主要关注城市发展和住房的问题(图3),这些领域在过去则由房地产的投机者所主导。他们的努力促成了战前时期的首个合作住房计划(图4)。但战争结束了这一切——挪威在1940-1945年间遭到德军的占领,到了战后,许多事情都发生了变化。1945年战争结束后带来的战略性飞跃改变了建筑师遵照行事的政治现实,建筑师也开始参与改变现实社会。因此,这正是我们的故事开始的地方。

挪威:挪威人口仅500多万,分布于大小约为德国的面积之上/Norway. The population of Norway, just over 5 million people, are spread over an area the size of Germany. (图片来源/Photo: https://pixabay.com/en/norway-fjord-villagepanorama-954895/)

沿海渔业传统:Fembøring渔船连同其他渔船是挪威沿海地区生活的必要组成/Coastal fishing traditions. The open Fembøring and other open fishing boats were essential for life along the Norwegian coast. (图片来源/Photo: lofotenfolkehogskole.no)

Architecture is a social endeavour, and so the work of architects is bound to the social and economic events of any society. In Norway in the last half of the 20th Century, this connection has been particularly close, argues Hans Skotte and Ingerid Helsing Almaas. But though the political influence of the profession may wax and wane, the work of talented architects remain as an inspiration across time and place.

The work of architects always relates to the prevailing power structures, or politics, in the societies in which they are engaged. As such, architecture reflects the aspirations of and symbolises those who can afford to engage architects. This has manifested itself from the pyramids and the Parthenon to Palladio and Pugin. Architecture was part of the colonial framework as Western culture imposed itself on other parts of the world, and it was a significant symbol of the independence when these same colonies fought for liberation 300 years later. Into the 20th Century, modernist architecture displayed the aspirations of newly established nations. Today, how are we to understand the architecture of Ground Zero, for example, if not as a highly charged political symbol?

Yet architecture is much wider than merely the output of trained architects. At a reasonable estimate, a mere 5% of the global built environment stems from the work of trained architects. The rest is the work of engineers at one end of the scale or vernacular self-builders at the other. In Norway, however, architects have been more dominant in shaping our modern environment than in most countries - at least until recently. This is primarily the consequence of the strength of the Norwegian economy and the capacity this has given us to constantly extend and renew our building stock, a practice which also relates to our historical dependency on the relatively short lifespan of timber structures. The reciprocity between the built environment and the political forces that shape it is of course visible in all advanced societies, but even so architects and architecture may have played a more significant political role in the development of modern Norway than in many other countries. Norway (Fig.1) is scarcely populated, with a population of about 3 million people in the early 1950s (rising to about 5.2 million today), spread across a land mass of some 325,000 square kilometres, about two-thirds the size of Inner Mongolia. So even well into the 20th Century the architecture profession was small by any standard, and the influence it had was predominantly grounded in the professional commitment and social responsibilities that architects shouldered in the years following World War II.

Post-war reconstruction

Acknowledging that the story of today rests on the history of yesterday, some threads into Norway's pre-war past are required. Historically, Norway has had no feudal system or aristocracy to construct country estates or palaces. The country has a strong coastal economy based on fisheries (Fig.2), and an agrarian tradition with its own built-in inequalities. Following industrialisation in the 19th Century, the labour movement emerged as a significant political force, which in the 1930s came to dominate much of Norwegian politics. Many architects joined the movement, usually more out of conviction than class. Those within the movement focused their energies primarily on urban development and housing (Fig.3), which was until then the domain of property speculators. These efforts resulted in the first co-operative housing programs (Fig.4) of the pre-war period. However the Second World War put an end to all that - Norway was under German occupation from 1940-1945, and after the war many things changed. The strategic leap that took place after the end of the war in 1945 significantly changed the political realities in which architects acted, realities that architects also helped change.Therefore, this is where our story will start.

托尔绍夫:位于奥斯陆托尔绍夫的新古典主义住宅,由市政住房当局设计并于1918-1923年建成/Torshov. Theneoclassical housing blocks at Torshov in Oslo were designed by the municipal housing authorities and built 1918-1923.(图片来源/Photo: krogsveen.no, http://krogsveen.no/Selgebolig/Solgte-boliger/Bolig/Leilighet/Agathe-Groendahls-gate-5-891158696)

艾塔斯塔德:“Etterstad Palace”是奥斯陆最早的合作住宅项目,由雅各布·克里斯蒂·谢兰设计,于1931年建成/ Etterstad. The "Etterstad Palace", one of the first co-operative housing projects in Oslo, was designed by Jacob Christie Kielland and completed in 1931.(图片来源/Photo: obosno/ wikimedia commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:OBOS-borettslaget_Etterstad_1..jpg)

瑞典房子的现状:位于克里斯蒂安松的瑞典房子现状/ Swedish houses today. The Swedish houses as they appear today, in Kristiansund. (图片来源/Photo: 由作者汉斯·斯科特提供/provided by Hans Skotte)

敌对势力长达5年的占领彻底破坏了挪威最北部地区的基础设施,建筑师们从这里开始了行动。除了重启经济发展,住房建设是人们优先关注的行业(图5、6)。在这一乐观的战后年代建设的住宅项目具有很强的社会关注度,房屋和公寓的功能性往往很强,甚至比现在的开发商建设的住宅实用性更高。体现国家公共意愿、具备专业性和社会信任度,这使得建筑师成为了建设战后环境的中心角色之一。在战争中经历了流亡的人们带回了关于现代住宅和城镇、区域规划方面的创新性思想——刘易斯·芒福德在这一领域产生了重要的影响力。一些返回祖国的建筑师在战后重建的国家机构中继续担任战略职务,他们很快叫停了在战争年代制定的重建计划(图7),因为这些计划显得过于“德式”,也太老套了。他们想寻找一种更为现代化和国际化的规划方法。然而,因为时间的紧迫性和当时专业能力的局限性,大多在战时制定的计划还是得到了实施——虽然他们有着明显的“德国味”。

从功能至上到对反技术治国运动

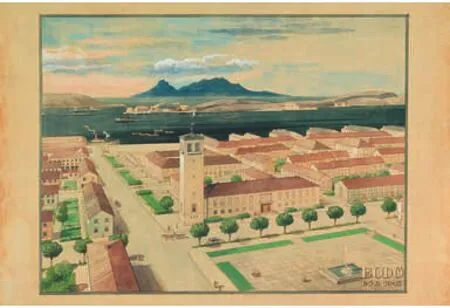

7博德:二战后的博德重建规划,由斯维勒·彼得森主持的BSR事务所设计;水彩画作者雅各布·汉森,1943年/Bodø. Plan for the reconstruction of Bodø after World War II, by BSR, the office for reconstruction headed by architect Sverre Pedersen. Watercolour by Jacob Hanssen, 1943.(图片来源/ Photo: The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Norway/Dag André Ivarsøy)

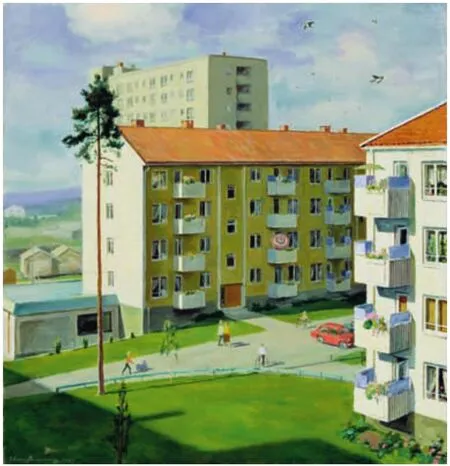

8兰贝斯特:位于奥斯陆兰贝斯特的住宅方案,由弗罗德·林南和奥拉夫·特韦滕于1950年设计,水彩画作者阿尔内·斯滕森/Lambertseter. Scheme for housing at Lambertseter in Oslo by Frode Rinnan and Olav Tveten, 1950. Watercolour by Arne Stenseng.(图片来源/Photo: Oslo Museum)

住房不仅仅是由建筑设计、砖头和砂浆组成的。居住,无论作为动词还是名词,都和家庭息息相关。在战后的挪威,政府鼓励人们拥有自己的家,希望人们进行储蓄并将钱投入到建设自己的家园中去。同时,政府也对保护私有财产进行了立法,并用相关的经济激励措施来支持这一政治前提。挪威的战后住宅(图8)由独立运营的合作社来组织开发,由新建的国家住房银行资助其建设,并由居民自身来对其进行管理。这使得建筑师能与用户群体保持密切的联系,可能也解释了早期的战后住房项目为何功能性特别优越。但是在整个1950年代末和1960年代,建筑师的政治作用和影响力逐渐被削弱了。住房和建筑逐渐成为了可量化的商品,由官僚来进行开发管理。这一时代的建筑只注重数字。在奥斯陆的周边建起了第一个具有普适性的高层郊区居住区 (图9),这一住区的建筑由许多著名的建筑师进行设计,各种建筑风格被统一在“实用主义”的标签之下。这一崇尚技术性的转变发生在了二战后的世界大多数地区,催生了全球性的反应,并最终导致了1968年5月在巴黎发生的学生骚乱以及随之而来的反殖民主义思潮。

9阿梅鲁德:1968年,哈康·米耶尔瓦和佩尔·挪森为阿梅鲁德的6000居民规划的住宅项目/Ammerud. Håkon Mjelva and Per Norseng planned the housing project for 6000 people at Ammerud, 1968. (图片来源/Photo: Office for Cultural Heritage, Oslo; http://www.oppdaggroruddalen. no/Omraader/Ammerud/Plan-og-arkitektur/Arkitektur-ogplanlegging)

10布林肯,1978年:对奥斯陆的历史街区坎彭的保护工作/ Brinken, 1978. Working to preserve the historic neighbourhood of Kampen, Oslo, 1978. (图片来源/Photo: Robert Lorange/kampenhistorielag.no)

建筑是一种社会化的活动,因此大多数的建筑师都是公众眼中的专业人士。随着这种要求变革的思潮的产生,许多被边缘化了的建筑师重新进入了公众视野。这些建筑师首先代表了反对由官僚主义或技术治国主义来主导城市规划的声音,出现在了从都柏林或者说柏林,再到简·雅各布斯的纽约等诸多城市。此后,建筑专业的人士开始提出新的城市问题解决方案,并根据新时代的需求着手开发务实的物质干预手段。这也是城市保护运动的开始:根据城市技术专家的论证,本来要组织拆迁的旧城,通常属于工人阶级社区的这些地区突然沐浴在了新的阳光之下,并被赋予了新的价值。许多建筑师亲自参与到保留和恢复整个街区旧建筑的项目中去(图10)。他们不仅广泛活动,也通过公开抗议让今天许多被我们认为是城镇中最珍贵资源的历史街区在被拆除的命运中幸免。活跃在这些辩论和反抗计划背后的常常是建筑师和建筑学专业的学生。

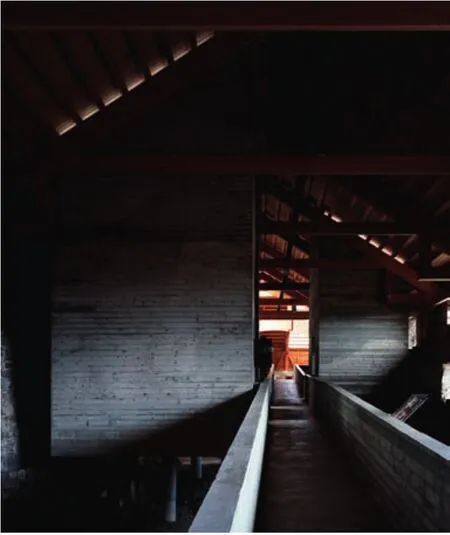

11 Storhamarlåven:海德马克博物馆,哈马尔;过去与现在相交,斯维勒·费恩,1967-2005/Storhamarlåven. Hedmark Museum, Hamar. Where past and present meet. Sverre Fehn 1967-2005. (摄影/Photo: Helene Binet)

12沿海渔业:现今位于罗弗敦的沿海渔业仍部分依靠小型渔船/Coastal fisheries. Today's coastal fishing at Lofoten is still partially done from small boats.(图片来源/Photo: Einar Stamnes/Aftenposten)

Emerging from five years of hostile occupation and the total devastation of the built infrastructure of the northernmost part of Norway, the architects mobilised. Aside from kick-starting the economy, housing became the prioritised sector (Fig.5, 6).The housing units built during the optimistic postwar years had a strong social focus, and the houses and apartments were often of a higher standard of usability even than those built by today's housing developers. The sense of a common national purpose, embodying professional and social trust, made architects some of the central actors in the shaping of the post-war environment. However, those who had been in exile during the war brought back innovative ideas on modern housing and on town and regional planning - Lewis Mumford became an important influence in this respect. Some of these returning architects went on to hold strategic positions in the state apparatus for postwar reconstruction, and they soon put a stop to the reconstruction plans that had been drawn up during the war years (Fig.7), as they were seen as being too "German" or too old fashioned. They wanted a more modern and international approach. However, due to time constraints and the limited professional capacity available, most of the war time plans were in fact implemented - despite their perceived "German-ness".

From functionalism to the reaction against technocracy

Housing is more than architectural design, bricks and mortar. Housing, both as a verb and a noun, is about the home. In post-war Norway, people were encouraged to own homes and to save and invest their savings in their homes. Property legislation and economic incentives were introduced to support this political premise. Norwegian postwar housing (Fig.8) was organised as independent co-operatives, funded by the new State Housing Bank and managed by the inhabitants themselves. This brought the architects into close contact with the user groups, which may explain the highly functional quality of the early post-war housing programs. However throughout the late 1950s and 1960s the architects' political role and influence waned. Housing and architecture gradually became all about numbers, in other words, it was a quantifiable commodity, managed by bureaucrats.The first repetitive high rise suburbs (Fig.9) sprang up around Oslo, designed by respectable architects in a style loosely labelled "pragmatism". In general this technocratic shift took place throughout most of the post-WWII world, and finally resulted in a world-wide reaction, culminating in the student riots in Paris in May 1968, and the counter-culture that followed.

Architecture is a social endeavour, making most architects publicly minded professionals. Consequently, a great number of the marginalised architects re-entered the scene as this shift took place. First as voices of opposition to the bureaucratic or technocratic approach that dominated urban planning, as was the case throughout many cities, from Dublin or Berlin to Jane Jacobs' New York. Next, architecture professionals started proposing novel urban solutions and developing actual physical interventions in response to the demands of a new age. These times also witnessed the birth of urban conservation: old, often working class neighbourhoods, scheduled for demolition by city technocrats, were suddenly seen in a new light and given new values. Many architects engaged personally and practically in saving and restoring whole quarters of old buildings (Fig.10). Not only did they prevail, but much of what are today the most cherished historic neighbourhoods of our towns and cities were saved from destruction by these public protests. Behind the arguments and counter-proposals were often architects and architecture students.

These were times of critical change. The protests were the first signs of opposition to the bureaucratic state. What followed was a political shift: individualisation, privatisation and finally neo-liberalism - and a cultural postmodernism which also engulfed architecture. Internationally, architects followed the flow of capital with an increasing inward-looking obsession with theorising and aesthetics. As societal trust in the profession waned and the sense of common purpose slowly evaporated even in Norway, so did the concept of "public" housing. Housing became less a question of providing people with homes and more a question of providing them with investment opportunities.

Still, impressive architectural work was being done during these years by exceptional architects. Storhamarlåven (Fig.11), the museum project at Hamar by Sverre Fehn, is an outstanding example - grounded as it is in a sophisticated and profound discussion of the interplay between built history and the architecture of today. Also within the postmodern idiom some fine buildings emerged. However, these were individual endeavours, not a consequence of societal solidarity or public policy. It took a couple of decades, well into the 1990s, before architecture again started to emerge as a politically relevant force with the power to make a societal contribution.

Building to support the districts

Although around 80% of the 5.2 million people in Norway live in towns and urban centres scattered thinly across the whole of the country, only the capital, Oslo, reaches over one million inhabitants. This demographic pattern of a thin spread of small towns and villages is a result of the political strength of the periphery, very much a legacy of the country's history and its dependence on natural resources, namely small scale farming and fishing (Fig.12). Norway has a coastline of 25,000 kilometres, almost twice the length of the coast of China, which gives ready access to rich fishing grounds. This decentralised pattern of population has been protected by post-war policy and supported by state investments in the outlying districts, investments like schools, kindergartens, hospitals and health facilities, care homes, cultural (Fig.13) and religious institutions and sports facilities. This has in turn has called for architectural interventions to define the public sphere. Up until the turn of the 20th Century, architectural competitions were held to ensure that these investments were of the high architectural quality that their underlying social purpose called for.

这是个孕育重大变革的时代。抗议是反对官僚主义治国的第一阶段。紧接着而来的是政治上的转变:个人化、私有化,以及最后到达新自由主义和一些后现代主义的文化思潮都开始影响建筑。在国际上,建筑师追逐着资本的流动方向,越来越沉迷于对理论和美学的内在追求。即使在挪威,社会对建筑专业的信任度也逐渐衰减,公众的共同目标感缓慢消失,“公共”住房的概念也是如此。对住房问题的探讨开始更少关注如何让人们承载他们的家,转而关注如何为人们提供投资机会。

不过即使在这些年,那些杰出的建筑师仍然在创造令人印象深刻的建筑作品。由斯维勒·费恩在哈马尔设计的博物馆项目Storhamarlåven(图11)就是一个杰出的例子,这一项目探讨了历史街区与今天的现代建筑之间复杂而深刻的相互作用关系。在后现代的语境中也出现了一些精品建筑。然而,这些作品都是凭借个人努力,而不是社会团结或公共政策作用的结果。直到几十年后的1990年代,建筑才再次开始成为具有社会贡献作用的政治力量。

支持地区发展的建筑

虽然挪威520万人口中约80%都居住在全国各地的城镇和城市中,但只有首都奥斯陆才有超过百万人口的居民。这种居民稀疏地分布在各个小城镇和村庄中的人口模式是首都外的政治力量角力的结果,也源于国家的历史传统中对自然资源、小规模农业和渔业(图12)的依赖。挪威拥有25,000km的海岸线,几乎是中国海岸线长度的两倍,可以方便地到达资源丰富的渔场。这种去中心化的人口格局受到战后政策的保护,国家对首都外地区的投资也得到保护,投资的对象包括了学校、幼儿园、医院和保健设施、护理院、文化(图13)和宗教机构以及体育设施等。这种政治模式要求通过建筑的干预来界定公共领域。到了20世纪初,各地都会通过举办建筑设计竞赛来确保这些投资能得到和其所体现的社会目的相匹配的高质量建筑。

所有这些设施的兴建都是为了支持当地的地区活动,或是为居住在大城市中心地区以外的人们提供平等的机会。其中对儿童看护设施的投资也是1960和1970年代妇女解放运动的结果。挪威现在是在两性平等方面世界排名最高的国家之一,因此在建设幼儿园和儿童日托中心方面存在着根深蒂固的性别优先政策。通过这一系列的公共项目(图14),建筑师和规划师为全国建筑环境的现代化建设做出了贡献,也许在某些方面也帮助了边远地区的社区保持了存在的目的感,甚至是自豪感。

这些散布的社区中的许多都在“美景路线”沿途,在这些异常美丽的风景中有公路穿过。近年来,挪威公路行政管理局已经投入数百万经费,为旅客建造休息站(图15),让人们能在沿途驻留、观赏景观;由年轻建筑师设计的这些宝石般的小建筑提升了人们欣赏挪威拥有的令人窒息的美景时的体验。这些投资也被视为对当地旅游业的公共资助,因此也符合广义的地区发展政策。

国家旅游线路计划是在1990年代初制定的一项政治举措。当时,建筑学正处在重新进入影响国家政治的时期,这一计划得到了当时的文化部长奥瑟·克莱韦兰作为一个艺术家的个人倡议。在那之前的几年中,很少有人关注城市环境的公共场所属性。而这一计划带动了相关立法,确保了城市设计的最低标准,也成立了相关的政府组织来传播好的想法,推动市政当局和公共机构为其所处的物质环境承担更多的责任。

在这几年中,国际建筑界也开始对挪威建筑师的一些工作感兴趣。这反过来又有助于巩固建筑师在国内的地位,并且允许他们尝试更多具有探索性和国际影响力的工作。大约10年前,政府通过与建筑行业的密切合作,发布了第一个国家性的建筑政策。这是一个值得称赞的倡议——虽然迄今为止似乎还没有因此产生任何广受好评或是具有实质性的建筑作品。

发达的经济与本地人才

世界上第一位研究和平学的教授约翰·加尔通为经济和社会发展的“北欧模式”发明了一个简短却广为流传的解释:发展=生产×分配。北欧模式受到世界银行和世界各国进步经济学家的好评,至今仍是全球化经济发展的参考模板。各种不同版本的加尔通原则在二战后期间指导了挪威的经济政策和公众理念。在其指引下,世界银行的研究显示挪威是世界上不平等性最低的国家之一。但是,我们同时也是全球新自由主义经济的成员,社会的平等性正因此面临威胁。挪威的建筑学和建筑业作为政治现实的一部分,也正面临新的挑战。面对这种情况,国家的法律和良好的文化政策能起的作用通常不大。但挪威的情况有其独特之处。

13 弗莱克峡湾文化中心,海伦与哈德建筑事务所,2016/FlekkeThord Cultural Centre. FlekkeThord Cultural Centre. Helen & Hard, 2016. (摄影/Photo: Jiri Havran)

14 富鲁塞特图书馆,奥斯陆:一个多功能面向说有年龄层的公共场所;Rodeo建筑事务所,2016/Furuset Library, Oslo. A place for many activites and people of all ages. Rodeo Arkitekter, 2016.(摄影/Photo: Sverre Christian Jarild)

罗尔斯蒂根瞭望台:国家旅游线路上的罗尔斯蒂根瞭望平台,雷于尔夫·拉姆斯塔建筑事务所,2012/Trollstigen lookout. Lookout platform on the National Tourist Route Trollstigen. Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter, 2012. (图片来源/ Photo: © 2011 diephotodesigner.de; www.diephotodesigner. de)

These public facilities were constructed to support local activities and initiatives or to secure equal opportunities for people living outside the large urban centres. Investing in child-care facilities was also a result of the women's liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s. As Norway is now one of the top-scoring countries (Fig. 14) in the world when it comes to gender equality, there are deep-rooted gender policies embedded in the construction of kindergartens and day-care centres. Through the whole range of public projects, architects and planners have contributed to the modernisation of the built environment throughout the whole country, and may in some ways also have helped outlying local communities retain a sense of purpose, even pride.

Many of these "off-the-grid" communities are reached by way of "scenic routes", roads passing through exceptionally beautiful landscapes. In recent years, the Norwegian Public Roads Administration have invested millions in creating rest stops for travellers (Fig.15), places to stop and view the landscape along these routes. These rest stops are frequently small gems designed by young architects, heightening the experience of passing through the beautiful and breath-taking landscapes that Norway has to offer. These investments are also conceived as publicly funded support for the local tourist industry, and as such are also in line with a broader regional development policy.

The National Tourist Route Program was the result of a political initiative in the early 1990s. At that time, architecture was returning to the stage of national politics, primarily through the initiatives of the then-Minister of Culture Åse Kleveland, an artist in her own right. During the preceding years, the public aspect of the urban environment had been given scant attention. This changed as laws were passed securing minimum standards of urban design, and government organisations were established to propagate good ideas and nudge municipalities and public institutions to take on a broader responsibility for their immediate physical environment.

亚历山德里亚图书馆:斯内赫塔于1989年获得位于埃及亚历山德里亚的新图书馆国际设计竞赛,该项目于2001年完工/Alexandria Library. Snøhetta won the international competition for a new library at Alexandria in Egypt in 1989. The building was completed in 2001. (图片来源/ Photo: Snøhetta)

During these years, the international architectural press began to take an interest in the work of Norwegian architects. This in turn helped to strengthen their domestic standing, and allowed for more explorative and internationally commended work. About ten years ago the Government - in close collaboration with the profession - issued their first national architecture policy. Though it was a laudable initiative, nothing sensational or even tangible seems to have emerged from it so far.

Economic success and local talent

Johan Galtung, the world's first professor in Peace Studies, is the author of a short and much popularised explanation of the "Nordic model" of economic and social development: Development = production × distribution. The Nordic model has been much praised by the World Bank and progressive economists throughout the world, and it remains a fixture in the global economic discourse. Different versions of Galtung's principle have guided the economic policies as well as public perceptions in Norway throughout the post-WWII era. As a result, Norway is one of the world's least unequal countries, according to the World Bank. But we are partners in the global neo-liberal economy, and as such that social equity is under threat. Norwegian architecture, and the business of architecture as part and parcel of this political reality, are also facing new challenges. Under such circumstances national laws and well-intended cultural policies play a lesser role. Yet Norway emerges unique.

卡西亚合作社:蒂因-特内斯图恩建筑事务所于2011年在苏门答腊岛设计的肉桂生产训练中心,在当地居民和建筑学生协助下建成/Cassia Coop. TYIN tegnestue designed a training centre for cinnamon production on Sumatra in 2011, built with the help of local people and architecture students.(图片来源/Photo: Pasi Aalto/TYIN tegnestue)

Why? Norway has oil. Since the early 1970s the oil economy has made Norway enviously rich, both as a nation and as private citizens. Though there are fewer and fewer people employed in the oil industry, the income from nationalised offshore oil extraction has filled public coffers for decades. We have had the means to build buildings, resources that could have exploded into architectural excess echoing the oil nations of the Middle East. But this never happened. In Norway, the ethos of social equality still prevails - albeit under some stress. This has to some extent prevented us from channelling our riches into luxurious structures - in the recent competition for a new government building in Oslo, for example, the only qualities specifically required by the programme were that the building be "modest" and expressive of "Norwegian values".

Furthermore, we have had a steady trickle of architectural talent capable of giving form to this social ideal. Snøhetta are a case in point. After winning the international competition for the Alexandria Library (Fig.16) in 1989 as mere youngsters, they have not only become international "starchitects", but more importantly they have made innovative contributions to Norwegian architecture and design at home. Snøhetta as a national brand has thus played a crucial role in heightening public awareness of architecture within Norway today.

论及原因,是因为挪威有石油。自1970年代初以来,无论作为一个国家或是作为个人公民,石油经济都使我们富裕得引人称羡。虽然石油工业的从业人数已经越来越少,但国家近海石油开采的收入已经满足了未来数十年的公共财政所需。我们具备的建造技术,以及拥有的资源足以造出超越中东石油国家的宏大建筑物,但却从来没有这么做过。这是因为在挪威,虽然面临一些压力,社会平等的精神仍然盛行。这在一定程度上阻止了我们将财富转化为豪华的建筑物,例如最近在奥斯陆的一座新政府大楼的竞标中,计划书中唯一的一项对设计品质的要求就是建筑物要“温和”,能体现“挪威的价值观”。

此外,我们也拥有一个稳定的建筑人才库,有能力实践这种社会理想。斯内赫塔建筑事务所就是一个例子。 他们作为一群年轻人在1989年获得了亚历山德里亚图书馆(图16)的国际竞赛大奖,之后不仅成为了国际上的“明星建筑师”,更重要的是为挪威的建筑和设计方面做出了创新性的贡献。作为一个民族品牌,斯内赫塔在提高挪威当今的建筑的意识方面发挥了至关重要的作用。

除了斯内赫塔之外,一些其他挪威公司也一直活跃在国际舞台上,其中的大多数是规模较大的公司。较小的公司则依靠国内的工作量就已经足够运营了。不过目前,建筑行业正在经由合并和收购发生重组,规模较小的建筑、景观和工程类公司常常被较大的公司并购,而这些大公司通常是国际化的工程咨询公司。这种情况反映了现行的商业环境,以及与建筑行业相关的新的国家规章和制度。传统的建筑师和客户之间的联系方式也因此被严重削弱;建筑师现在主要是与工程承包商之间发生关系了,有些人会说建筑师是被承包商“束缚”了。在城市规划领域,这也导致了“由承包商驱动”的城市发展实践,这一力量越来越多地打破了委托建筑师和规划师来为公共利益服务的传统——在由左派和右派共同组成的中间派政府的一贯政策下,本应该服务公众的规划目标开始让位于私人投资者的经济利益。

建筑界的反抗

自行车驿站:位于利勒斯特伦火车站的自行车驿站,远距离的上班族可以在搭乘火车前停放他们的自行车;由多个建筑师设计,2016/Bicycle hotel. Bicycle hotel at Lillestrøm train station, where commuters can park their bicycles before getting the train. Various Architects, 2016.(摄影/Photo: Ibrahim Elhayawan)

但是,我们也再次看到了建筑师们的反抗。新的建筑从业者们基于不同的目标创立了各自的小公司,这些小公司具有多元性和互补性,许多公司坚持将焦点放在本地区,但也和其他小公司建立战略合作伙伴关系。这些努力需要成本来支持,许多小公司在维持经营和实现新想法上挣扎着,其中的一部分获得了成功,更有一些则获得了巨大的成功。蒂因-特内斯图恩建筑师事务所(图17)也许是最热门的例子。继在南方国家开展了一系列基于社会目的的小型实践并得到广泛报道后,他们成了唯一被邀请参加2016年威尼斯建筑双年展主展览的斯堪的纳维亚公司。蒂因-特内斯图恩的创始人在开始创业时只是学生,但在几年间,他们在国际建筑新闻界获得的报道比包括斯内赫塔在内的其他斯堪的纳维亚建筑公司更广泛。尽管他们的作品到目前为止都较为温和,但他们所获得的关注也证明了建筑行业的转变:建筑师正在脱离他们的后现代美学专家的角色,转而关注当今时代面临的更为迫切的挑战,例如社会公平和全球资源的可持续利用。

建筑与政治间有着千丝万缕的联系,而政治也与公众情绪密不可分。建筑师在二战之后扮演的直接政治角色的时代早已过去了。对于当今挪威个性化的消费者来说,建筑主要传递的是个人兴趣。目前的右派保守政府已经将住房和城市发展完全托付给了自由市场经济。挪威的建筑师现在还不能大幅地影响公众情绪,从而恢复在政治上的重要地位。他们仍然在政治上被边缘化,专业发挥的空间也受到承包商和一系列专业顾问的挤压。面对当前的建筑实践与资源短缺、气候变化问题之间不可避免的冲突矛盾,他们有可能起到的潜在关键作用也许也会因为那些将可持续性(图18)作为市场发展机会的专家的存在而被减弱。例如,节能现在已经成为整个建筑行业的关注焦点,但这并不是一个由建筑师主导的专业领域。不过,社会的可持续性目前尚未明确地被定义,因此挪威的建筑界也并未完全失去其重要性(图19)。

在过去的10多年间,挪威的建筑师们针对21世纪人类面临的重大挑战,实验、调查、设计并建造了一些真正具有创新性的建筑(图20)。这些建筑不止于遵循法律法规的要求,也不屈从官僚政府的指引,而是通过对空间和物质的具有创造性的革新和设计来回应社会问题。无论这些作品的作者们的政治影响力如何,这些建筑都将成为未来的挪威和海外建筑师们的参考和资源。

In addition to Snøhetta, there are a handful of other Norwegian firms consistently active on the international scene, most of them being larger firms. Smaller practices have had mostly plenty of work at home. Currently however, the profession is being restructured through agglomeration and acquisitions, whereby smaller firms of architects, landscape architects and engineers are bought up by larger, often international consultancies. This is a response to the prevailing business climate as well as to new national rules and regulations governing the building industry. As a result, however, the traditional link between architect and client has been severely weakened and architects are now mostly contractually linked, some would say "chained", to a contractor. In the field of urban planning this has led to a practice of "contractor driven" urban development, which is increasingly outmanoeuvring the traditional public interest mandate of architects and planners - public aims have been giving way to the interests of private investors, with the blessing of a succession of centrist governments both from the left and the right.

Architectural reactions

But again, we see architects react. Small startups are being established by new practitioners with different aims, small firms diversify and collaborate whilst others stubbornly continue to work with a local focus and in strategic partnership with other small offices. Though these efforts come at a cost and a lot of smaller firms struggle both economically and in the realisation of new ideas, some succeed while others succeed magnificently. TYIN tegnestue (Fig.17) is perhaps the most arresting case in point. Following a string of small, socially motivated and widely published projects in the global south, they were the only Scandinavian office to be invited to the main exhibition of the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. TYIN began as mere students, but a few years ago they had had a wider coverage in the international architectural press than any other Scandinavian architecture practice, Snøhetta included. Though their oeuvre so far is modest, the attention they have received bears witness to a shift in the profession: architects are leaving their postmodern role of aesthetic specialists to focus on addressing the more urgent challenges of our time, like social equity and a sustainable use of global resources.

Architecture is inextricably linked to politics, and politics is inextricably linked to public sentiment. The direct political role architects played in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War is long gone. For the individualised consumer citizen of present-day Norway, architecture is an issue of only passing interest. The current right-wing conservative government has left the architecture of housing and urban development completely in the hands of the market. Architects in Norway have not yet been able to significantly influence public sentiment and thereby reclaim political prominence. They remain politically marginalised and professionally squeezed between contractors and an array of specialised consultants. Their potentially pivotal role in the inevitable showdown between current building practices and resource scarcity and climate change may be eclipsed by specialists who see sustainability (Fig.18) as a market opportunity. Energy conservation, for example, is by now established as a concern for the whole of the building industry, by no means a specialist domain for architects. Social sustainability, however, has yet to be clearly defined but nevertheless, it is an area where the Norwegian architectural profession has never entirely lost focus (Fig.19).

Architects in Norway have over the last decade or so experimented, investigated, designed and built truly innovative buildings (Fig.20) responding to the momentous challenges of the 21st Century. This is not guided by the requirements of laws and regulations or by bureaucratic demands, but rather through sheer creative spatial and material innovation and design. Irrespective of the political influence of their authors, these built works will be a reference and a resource for future architects in Norway and abroad.

Action and Reaction: The Work of Architects in Norway

The work of architects always relates to the prevailing power structures, or politics, within the societies in which they are engaged. In Norway the architectural profession has been grounded in political developments since the Second World War, starting with reconstruction efforts, particularly in the area of housing. As the economy of housing construction made urban development increasingly technocratic, the 1960s and 1970s saw a strong public as well as professional reaction which focused on conservation and environmental values. Outside the urban centres, national policy was dedicated to supporting regional economies, and architects have been essential in shaping the physical environment of smaller communities throughout the modern welfare state. Today, as the profession operates within a narrowing band of influence, the creative talent of many Norwegian architects makes their work a resource and an inspiration in Norway and abroad.

Norway, post-war reconstruction, housing politics, technocracy, conservation, public welfare, gender equality, the Nordic model

学生住宅:位于特隆赫姆的学生住宅。挪威最高的用交错层压木材(CLT)建造的结构之一;MDH 建筑事务所,2017/Student housing. Student housing in Trondheim. One of the tallest structures in the country built with CLT-elements (cross-laminated timber). MDH Arkitekter, 2017。(摄影/Photo: Ivan Brodey)

斯迈斯特回收中心:位于奥斯陆斯迈斯特的回收中心,公众可以直接向此中心运送回收物品;隆格瓦建筑事务所,2015/Smestad recycling. Recycling centre at Smestad in Oslo, where the public can deliver goods for recycling. Longva arkitekter, 2015. (摄影/Photo: Einar Aslaksen)

挪威科技大学建筑与设计学院,《建筑N》/Faculty of Architecture and Design, NTNU; Arkitektur N

2017-05-10