Conversation with presence:A narrative inquiry into the learning experience of Chinese students studying nursing at Australian universities

2017-07-05CarolChunfengWang

Carol Chunfeng Wang

School of Nursing and Midwifery,Edith Cowan University,Perth,Australia

Conversation with presence:A narrative inquiry into the learning experience of Chinese students studying nursing at Australian universities

Carol Chunfeng Wang

School of Nursing and Midwifery,Edith Cowan University,Perth,Australia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Narrative inquiry

Story

Voice

International education

International students

Chinese students

Aim:the aim of this methodological article is to re flect on and extend current understandings of the possibilities of narrative inquiry research giving voice to students,and to expand the power of story by sharing the philosophical,theoretical,and methodological considerations of narrative inquiry in an international education context.

Background:there has been much discussion about the need in providing a‘voice’to people across the society,who feel marginalised in many contexts,including international students.There is limited research about Chinese students studying in Australia.In particular,the learning experience of Chinese nursing students has not been fully explored nor understood.

Discussion:to enhance teaching and learning in international education contexts,and to cater better to international students,it is important to understand their experiences and perspectives.There is no better way to achieve this levelof understanding than to let students'voices be heard,to let them speak for and about themselves because reality exists within these students'perceptions.

Conclusions:in the context of international education,narrative inquiry as a research methodology, when used with sensitivity and re flexivity,through the power of stories,offers a new dimension in the international education research.

©2017 Shanxi Medical Periodical Press.Publishing services by Elsevier B.V.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1.Introduction

There has been substantialdiscussion aboutthe need to provide a‘voice’to people across the society,who feelmarginalized in many contexts,including international students.1e5

A systematic review identi fi ed gaps in the existing literature. There is limited research on Chinese students studying in Australia. In particular,the learning experience of Chinese nursing students has neither been fully explored nor fully understood.6

To fi ll the research gap,Chinese nursing students need an opportunity to tell their stories and make their‘voice’heard rather than having the views,understandings and considerations held by Australian education bodies speak for them.6e8The aim in giving a voice to the students is to have them construct their own stories instead ofhaving the authorities and educators constructstories for them.7

In the context of internationaleducation,narrative inquiry as a research methodology,when used with sensitivity and re flexivity,9could add a new dimension to internationaleducation research.5,6

The purpose of this article is to explore and interpret the‘ontology(the nature of reality),epistemology(the nature of knowledge),and methodology(how that knowledge may be gained)’10aspects of the constructivist view that shaped and de fi ned my research,the‘Chinese nursing students at Australian universities:a narrative inquiry into their motivation,learning experience,and future career planning’.11Therefore,the aim ofthis methodologicalarticle is to re flecton and extend the possibilities of narrative inquiry research by giving a voice to students as wellas to expand the power of story within an international education context by sharing the philosophical,theoretical,and methodologicalconsiderations ofnarrative inquiry.My intention here is use the project as an example exploration of the issues Iraise.

The underpinning research structure of the‘Chinese nursing students at Australian universities:A narrative inquiry into their motivation,learning experience,and future career planning’project is shown in Fig.1,which is adapted from Tuli.10

Fig.1.The research structure of‘Chinese nursing students at Australian universities:a narrative inquiry into their motivation,learning experience,and future career planning’project.

Knowledge is created through socialinteractions within cultural settings.12e15The world is socially assembled,multifaceted,and constantly changing.To understand human values,beliefs,the meanings of social phenomena,and the complexity of the world, we need to understand cultural activities and experiences.10,16e19I am interested in understanding and unfolding the underlying structures and past experiences that affect the perceptions of individuals and groups.

To enhance teaching and learning for internationalstudents and thereby address their speci fi c learning needs,it is important to understand their experiences and perspectives.An optimalway to achieve this is to let their voices be heard,letting them speak for and about themselves.Reality exists within the students,especially their perceptions,because truth and value making is socially constructed and people make their own meaning of socialrealities.15

By understanding the stories of Chinese nursing students' learning experiences at Australian universities,Australian educators may gain insight into how to approach teaching and learning more effectively.Speci fi cally,nursing students'narrative accounts will enable Australian educators to understand this cohort of students better and thereby reconsider whether their taken-forgranted knowledge as educators fi ts within the context of international education.Moreover,educators may become more cognizantofwhat they do notknow about teaching and learning in internationaleducation.

2.Philosophical thought

2.1.Ontological considerations

Ontology refers to the nature of reality.10Since our origins, humans have been telling stories;narrative is centralto human life, and our narrative instinct was built to tell stories and share experiences.As was articulated by Barthes and Duisit,‘Narrative is present at all times,in allplaces,in allsocieties;indeed,narrative starts the very history of mankind…Like life itself,it is there,international,trans-historical,transcultural’.20Narrative allows us to comprehend,describe,and act within previous experiences;the story is how we make sense of the world.21,22Thus,we are interpretive beings,and storytelling is in our blood.When we seek to make sense ofthe stories we have lived,these processes can shape our lives in powerful ways.Our stories are created by connectingevents together over time;these events can shape the perceptions of our past as wellas have implications for our present and future actions.By telling and retelling stories,we interact and respond to and with one another;we share and understand who we are,who we have been,and who we are becoming.As Greene23describes‘some ofus may like pure theory,theology,or philosophy,but allof us like stories.It's where we see the spirit best’.23For me,stories heal and soothe the body and spirit as well as provide hope and courage to explore and grow.The process of storytelling,a fundamental element in narrative inquiry,provides the opportunity for dialogue and re flection,both intertwined and cyclical.

In narrative inquiry,ontological questions12e14,24to be considered are as follows:What is true?What exists?What is real?What are the fundamentalparts ofthe world and how they are related to each other?The purpose of these questions is to understand and describe the underlying structures that affect individuals'and groups'perceptions.14

A qualitative ontological perspective is underpinned by relativism.13,14Research in relativism involves searching for meaning in individuals'experiences such that relativism views reality as only existing within a context.Multiple perceptual constructions constitute reality.These realities are induced by experiences and social interactions;therefore,each person has his/her own reality. Relativism believes that realities are co-constructed;‘truths’are subjective,dynamic,and contextual,making knowledge contextual.Multiple,yetcon flicting truths are stilltrue and perceptions or truths may change with time.12e14,24

Relativism is an ontological perspective that leads to the constructivist paradigm of research.17,25Constructivists believe human beings construct meaning or reality based on interactions with their socialenvironments.They believe reality is created in the mind ofthe observer;thatis,we do notdiscoverknowledge,we constructit. Therefore,itispossible to have multiple,socially constructed realities.

The primary ontologicalconsideration in my research was to understand and describe the underlying structures that affect Chinese nursing students'learning experiences at Australian universities.The literature review6highlighted that there is a dearth of primary research on Chinese students studying in Australia.In particular,the learning experience of Chinese nursing students has neither been fully explored nor fully understood.Chinese nursing students'voices and narratives could challenge educational traditions,norms,and practice in an internationaleducation context.Teaching and learning could be improved if we capture these students'voices,as heard in their stories,and then re flect on,analyze and make sense of these experiences.Thisapproach willenable nurse educatorsto learn about and understand the collective needs ofstudents.

Rather than categorizing research data and viewing them from an objective stance,generalizing for ef fi ciency or to develop‘laws’, my research approach adopted the philosophical underpinnings of narrative inquiry,which acknowledges human experiences are dynamic and constantly in flux.26Stories could provide a primary means of understanding the pattern of an individuallife and story‘makes the implicitexplicit,the hidden seen,the unformed formed, and the confusing clear’.27

There is a growing interest in narrative inquiry for two reasons. One is a critique of the inherent strengths and weaknesses of conventionalpositivist research methods and another is a focus on the individualand the individual's construction ofknowledge.28My research aimed to highlight the possibilities that narrative inquiry offers through the power of stories.

2.2.Epistemologicalconsiderations

Epistemology is the nature of knowledge.10Stories are fundamental ways our brain organizes our experience of the world and then processes and presents the complex information in manageable narrative forms so that we can understand events that have occurred.After all,it is much easier to remember a story than a random collection offacts.We tellstories so thatwe can know what is happening;we listen to stories so we can understand how people think,or have thought,helping to understand their experiences. Narrative is an organization,acting as one way of thinking, knowing,and communicating about the world,which helps us to make sense of our experience.This in turn,helps us understand much more about our own history,literature,and ourselves. Therefore, storytelling is connected to knowing and knowledge.20e22

The epistemology of narrative research understands the world as created,understood,and experienced by individuals or groups in their interactions with other people and the broader social context.16,18,19,22,29The nature of narrative inquiry is constructive and inductive;that is,it is concerned with encounters,the process, and the deeper understanding of the research phenomenon.It is less concerned with generalizability.30The role and function of narrative research is to make sense of and to understand the complexity ofindividualsituations under research.To achieve this, it is important that the researcher builds a trusting relationship with participants to add depth and richness to the data.5The‘narrative researcher is in a dual role-in an intimate relationship with the participant and in a professionally responsible role in the scholarly community’.31

The epistemologicalquestions to be considered10,16,18,19,22,29are as follows:How do we learn?What is knowledge?How do people getto know something?Whatis true knowledge?How may a beliefbe justi fi ed?How do we know that something is true?And, what is the relationship between the participants and the researcher?

Constructivism believes that researchers and participants are co-makers of fi ndings.The research involves collaboration between the participants and researchers such that the research methods used are grounded on the interactive relationship between researchers and participants.5,30

Additionally,the epistemologicalview ofempiricism posits that true knowledge is established in response to our senses.Experience and observations are important references when beliefs and claims are justi fi ed and proven.32

Empiricist John Locke believed that knowledge comes from experience.24He believed there are only two ways we can acquire knowledge,sensation(look,listen,and touch)and re flection.24,32We obtain information from our senses.We see,hear,touch, taste,and smell things.The other way we obtain information is through ideas,which Locke called re flection.An example for this claim is:How would you explain colors to a blind person who has never been able to see?Locke believed the truth is only produced through our sensation;truth has nothing to do with the thing itself. For example,think about color:When you see a color changes under different lighting,is the color really in the object itself,or does it have to do with the way we perceive color under different conditions when we receive it?

Dewey,Johnson,Geertz,Bateson,Czarniawska,Coles,and Polkinghor had tremendous in fluence on narrative inquiry.22The theoretical underpinning of narrative inquiry is‘telling a story about oneself involves telling a story about choice and action, which have integrally moral and ethical dimensions’.33Therefore, narrative inquiry aims to‘sign up many truths/narratives’,33instead of fi nding one generalizable truth.The process of unfolding the story is thoughtto‘have the potentialto transform the participants' experiences’.33This is further expressed by McMillan and Price:‘Narrative performances not only provide sites to represent and to deconstruct diverse and ever-changing experiences of identitiesformation,but they are also potential spaces for democratic meaning making’.34

Instead of engaging numbers,statistical inference,and probability to provide a way of knowing and achieving reliability,‘narrative inquirers embrace the metaphoric quality of language and the connectedness and coherence ofthe extended discourse of the story entwined with exposition,argumentation,and description’.31Narrative inquiry desires to understand the human world instead of insisting on a single kind of truth.35The conception of validity and reliability in non-qualitative research relies on statistics that can prevent other ways of knowing.Rather than favoring the power of prediction and generalization,narrative inquiry aims at‘understanding the complexity of the individual’.31The process of telling,unfolding,and retelling the story itself is‘primarily an artful endeavor,it should be interpreted as an art form’.27van Manen beautifully settled this as such:‘After all,it is lived experience that we are attempting to describe,and lived experience cannot be captured in conceptualabstractions’.36

With respect to the voices and experiences portrayed in my research,a narrative inquiry helped to extend our present understanding of the common everyday learning experiences of international students in an Australian nursing program.Nurse educators may reconsider whether their taken-for-granted knowledge fi ts within the context of international education and may become more cognizant of what they do not know about the teaching and learning of international students.These reconsiderations and awareness could shift their teaching and learning approach to new or different understandings.While listening to and reading the students'narratives,I,as a researcher, interacted with the meaning and focused on what the students experienced rather than what I knew,which might be concealed rather than apparent.37

In narrative inquiry,both participants and researchers came to the interview with considerations of their own pasts and futures. The focus of the research may shift as participants concentrate on what is important to them.By trying to understand the narratives we create,we are better able to understand ourselves,our own literature,and our own history.In my research,as a methodology, narrative inquiry considers the participants as authors of their stories instead of the objects of research.10,31,38This highlights an empowering and enabling process for participants to make meaning oftheirown truths,value theirown creation ofknowledge through the process,and convey their interpretations freely,which they may not have had the opportunity to achieve with an outsider of the research.10

3.Methodological considerations

Narrative inquiry was fi rst used by Connelly and Clandinin39as a methodology to describe teachers'personal stories.Through stories,narrative researchers look for ways to understand and represent the lived experiences of participants.22,40This is supported by Lemley and Mitchell:

A burgeoning interest in narrative inquiry underscores how stories can explain experiences as well as serve as a catalyst for personaland socialchange in the lives ofthe participants telling the stories and in the lives of their audience.26

Narrative approaches permit a rich portrayal of individuals' experiences and search for the meaning that individuals tied to their experiences in a speci fi c context.Narrative inquiry ampli fi es voices that would have been silenced41and employs narrative as a way of communicating reality.42

My research aimed to revealthe experience of Chinese nursing students studying at Australian universities to honor and authenticate the voices of international nursing students from the mainland of China.Through the shared stories they possess,we have gained a deeper understanding of their experiences in Australia and how they strived for social and cultural change for themselves and others.Hearing stories,interpreting the fi eld texts of human experience,discovering and understanding the lived experience of Chinese nursing students studying at Australian universities was achieved through narrative inquiry.Whatwas then produced is an expanded understanding of human existence.43

Broadly,my research investigated‘the meaning of the lived experiences for several individuals about a concept or the phenomenon’.44The research employed narrative inquiry as the methodology because there is a‘long overdue recognition of the sound ofsilence,a sudden painfulawareness of the extent to which human voices have been systematically excluded from the kinds of traditional research texts’.45It was concerned with what is essentially irreplaceable because‘As persons,we are incomparable,unclassi fi able,uncountable,and irreplaceable’46cited in.36This approach allowed the participants to voice their experiences without constraints.

Ihave used narrative inquiry to understand internationalnursing students'experience and their interactions with others as an alternative way of knowing that involves curiosity,interest,caring,and passion.35The living and thinking of the research was grounded within Clandinin and Connelly's22understandings ofexperience as the centralaspect of narrative inquiry.They wrote that:

Because experience is our concern,we fi nd ourselves trying to avoid strategies,tactics,rules,and techniques that flow out of theoreticalconsiderations of narrative.Our guiding principle in an inquiry is to focus on experience and to follow where it leads.22

Engaged with a narrative inquiry viewpoint and using fi eld texts from multiple sources,the research intended to describe and interpret the rich narrative accounts of Chinese international nursing students'learning experiences in Australia.Ibegan from a not-knowing,inquisitive position and focused on questions that helped the storytellers address their senses,feelings,thoughts, attitudes,and ideas in the events they experienced.This illuminated portraits that captured vivid representations of their lived experiences.47

The intent of my research was to seek how international students make meaning of their experiences with the understanding that those meanings were various and context dependent.By using a narratives format to present fi ndings,I gained rich layers of information and understanding aboutthe particularities ofthis group of nursing students from their point of view.This knowledge has given me,as the researcher,as well as readers and nursing educators insights to recognize what parts of these stories educators could apply to their own practice in education.

Narrative research,arts-based inquiry,is simply an elegant and exceptionally useful way to uncover the nuances and details of lived experience.Narrative inquiry is not simply storytelling. Instead,it is a method of inquiry that uses storytelling to uncover nuances and enrich the analyses we can perform;also,narrating the fi ndings can lead to fresh insights and understandings.

4.Design

Clandinin and Connelly's expansion of narrative inquiry as a research methodology is deeply shaped by philosopher John Dewey.48e50As a philosopher of experience,Dewey,based his principles on interaction and continuity,theorized the key terms personal,social,temporal,and situation to describe the characteristics of experience.For him,to research life and education was to research experience,because education,life,and experience are one and the same.The research ofexperience is centralto narrative inquiry.49,50

The educational theorist John Dewey's48e50three-dimensional space narrative structure approach(interaction,continuity and situation)to fi nd meaning in research is centralto his philosophy of experience in a personal and social context.This approach posits that to understand people,such as international nursing students from mainland China,we need to examine not only their personal experiences but also their interactions with other people.Dewey's three-dimensionalapproach had a major in fluence on my research and the practice of narrative inquiry in many disciplines,such as education.The sense of fluidity in storytelling,moving from the past to the present or into the future,is at the heart of Dewey's theory of experience in the fi eld of education.

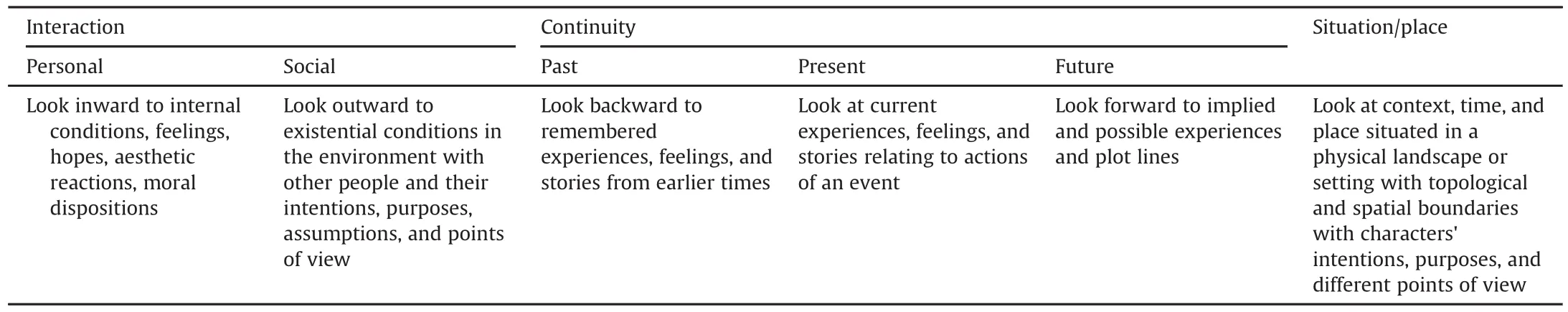

Based on Dewey's theories,Clandinin and Connelly22advanced the three aspects of this narrative approach,personal and social (interaction);past,present,and future(continuity);and place(situation),as shown on Table 1:

As detailed in Table 1,interaction includes both personal and socialcharacteristics.Using this framework,the researcher needs to focus on questions and analyze transcripts or fi eld texts of the participant's personal experiences along with his/her interactions with other people in relation to the story.These other people could have different purposes,interpretations,and opinions on the topic of the story,which will also inform the analysis.22

Continuity or temporality is essential to narrative research.To support this,when analyzing the transcript or fi eld texts for information,the researcher needs to consider the participants'past and present experiences,as illustrated in the description ofactions ofan event,and those actionsthey describe aslikely to occurinthe future.22

The situation or place also needs to be analyzed in a transcriptor fi eld texts.To do this,the researcher needs to search in the participant's landscape for speci fi c situations that give meaning to the narrative,such as the participant's physicalplaces or the sequence of the places and the impact these places have on shaping their experiences.22

As for my participants,I was once an international nursing student from mainland China.When I was working within the three-dimensional narrative inquiry space,my own experiences of being an international student would have been relevant to their narratives.As Clandinin and Connelly22state‘itis impossible…as a researcher to stay silent or to present a kind of perfect,idealized, inquiring,moralizing self’.Hence,due to my experiences as an internationalstudent,Iworked within the‘space’(past,present,and future)of my participants and myself.In doing so,my own unknown stories came to light as much as those of my participants.

I have seen myself in the midst of the three-dimensional narrative inquiry space;I have seen myself in the middle of my participants'stories and my own stories.My background gave me entry to their world and the reverse was true such that my voice was part of the story.

In the study,it was important that Iwas transparent about my interests to ensure a trusting relationship with the participants.It was also importantthat Iprovided a fullexplanation ofthe research before starting so that participants would not feel surprised or deceived later,ifor when they may have read the published report.

As guided by Clandinin31:‘this interpersonal dynamic requires that we be good containers,that we can listen empathically but nonjudgmentally,feeling from within the participant's emotional space rather than from the locus of our own idiosyncratic reactions'.31

5.Methods

My research gathered narratives via fi eld texts from multiple sources.The fi eld texts(usually called data)were created by participants and the researcher to present aspects of experience. Because the way that researchers enter the inquiry fi eld in fluences whatthey intend to discover,the data collection process is selective and the fi eld texts are shaped by the selective interestor disinterest of the researcher and/or participants.Therefore,composing fi eld texts was an interpretive and contextualized process of the text construction.22

5.1.Field texts

Engaged with a narrative inquiry viewpoint,I collected fi eld texts from multiple sources,including individual in-depth interviews,group discussions,observations,and conversations.

Factors affecting Chinese international students'communication challenges,such as English language barriers,6were alleviated by conducting interviews with students in their preferred language (Mandarin and/or English). All participants were given pseudonyms.

Studies acknowledged that culture determines communication behaviors.27,45,51Confucianism has been deeply embedded in Chinese culture.Having been exposed to the value of Confucianism, Chinese students often present with certain characteristics in their communication patterns,such as respectfulness toward teachers; saving face,indirect behaviors in verbal communication,gestures and facialexpressions,and quietness and silence.51At this cultural level,my ethnic background(Chinese),my personalexperiences as an international student,and my role as a nurse educator helped participants to be open and share their views and experiences.

5.2.Interviews

As explained by Chou,Tu,and Huang:‘In a life story interview, the interviewee is a storyteller,the narrator of the story being told, whereas the interviewer is a guide,or director,in this process.The two together are collaborators,composing and constructing a story the teller can be pleased with’.27

The participants hold the power of knowledge because they are the only experts on their lived experience.During the interviewprocess,as the researcher,what Ihad to offer to my participants was respectful and interested attention instead of my views.Via the practice sessions Ihad undertaken prior to conducting interviews,I also managed to minimize my personalbiases and culturally based assumptions.I remained open-minded to others'experiences.I conducted individual personal interviews,which took between 2 and 3 h each.I met participants at venues,such as public areas; of fi ces;cafes at university;or wherever was most convenient,quiet and comfortable for them.These interviews were in-depth and mostly involved the participant talking about his/her experience in Australia.An interview guide and interview probes were used as conversation starters and were only necessary during the interview. The interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed by me.

Table 1 The three-dimensional space narrative structure.

Iasked questions,such as‘What is your learning experience in Australia?’as an open-ended question thatwas a‘way ofinitiating a research conversation that re flects dynamic and organic,dialogical processes’.47As cited in Chou et al.,27Douglas(1985)suggested:

The most helpful questions would be those that guide the storyteller toward the feeling level.This is where the interview becomes active,and interactive,at its best,and where the most meaning in a person's life comes from.Getting to a deeper levelof reality can be achieved in various ways,from speci fi c types of questions to comments to sympathetic and responsive listening. The more interest,empathy,caring,warmth,and acceptance that can be shown,the deeper the response level will be.It is when these qualities are present in the interview that it can become a creative search for mutualunderstanding.

5.3.Group discussions

Ialso conducted a focus-group interview that gave the participants opportunities to re flect on their learning experiences in Australia while listening to other participants'stories.My participants developed comfortable friendships with each other due to the sharing of their interesting experiences prior to and during their time in Australia.The topics they shared included,but were not limited to,learning subjects,graduate attributes,food and eating habits,transportation,language,social life,happiness, friendship,dreams and ambitions.The interview took two hours and was audio recorded and then transcribed by me.

5.4.Conversation

I also encouraged my participants to communicate with me regularly via emails or any other media to update their experiences. Ialso sentthe regular group phone messages asking how they were doing and encouraging continualcommunication with me.

5.5.Data analysis

Data analysis was a process of making sense out of the fi eld texts.Based on the essences thatwere encoded inside ofthe stories and,expanded outward,the analysis was ampli fi ed to the fullest possible extent of resonance while considering multiple aspects, such as the entire substance of the fi led texts.I considered the nuances of tone,pauses,and breaks in the conversation;the observation of participants'interactions with other people and their social culturaldiscourse;their past and present experiences; their physicalplaces;and their dreams and ambitions.22

In analysis,the research employed both narrative representations and thematic analyzing approaches.

5.6.Thematic analysis

In using thematic analyses,I analyzed fi eld texts to‘arrive at themes that illuminate the content and hold within or cross stories’.52Thematic analysis is transparent,adaptable and rich in detail to translate different aspects of the research focus.It consists of speci fi c guidelines for‘identifying,analyzing and reporting patterns(themes)within the data and describing data in rich details’.53

In my research,the process ofthematic analysis followed the six phases(Table 2)outlined by Braun and Clarke.53

5.6.1.Phase one

Phase one involved attentive listening,transcribing,and becoming familiar with the raw data.As the researcher,I was the main instrument in the research.Once Ihad listened to the audio recording of the interviews several times,Icompleted the English transcriptions verbatim.For those interviews conducted in Mandarin,I fi rst translated them into English and then employed a professionalMandarin and English speaker to check the accuracy of the translations.Participants also checked the interpretation of the gathered transcripts.This check is a major step in narrative inquiry to preserve the integrity and authenticity of the stories told by participants.

This task took time and patience,but it was a valuable experience.It permitted me to be deeply engaged with the fi eld texts and enhanced my understanding for further exploration.Ialso‘checked the transcriptions back against the original audio recording for accuracy frequently to acquire authentic information from the interviews.53

5.6.2.Phase two

In exploring the fi eld texts,Ibegan the coding processes,which involved attending to fi eld texts in detail and then extracting the essence to capture tentative ideas for codes,issues and visible themes.54,55During this process,Igave equal attention to all fi eld texts.In retaining accounts from the fi eld texts,I coded as many potential themes as possible.Several meaningful sections were coded more than once to acquire a comprehensive thematic map.16,53

5.6.3.Phase three

In this phase,to identify themes,Icollected,combined,re fi ned, and incorporated the codes into potential themes and sub themes relevant to the research questions and literature.In this ongoingcoding and recoding process,the codes and themes were developed into further re fi ned levels to assist in explaining the thematic relationships in an in-depth analysis within and across the topics.16Ialso grouped the information that might need to be discarded in the next reviewing phase.

Table 2 Phases of thematic analysis.

5.6.4.Phase four

In this phase,themes were reviewed and re fi ned to warrant their adequacy,authenticity and trustworthiness.The thematic map generated in this phase presented links and relationships between themes.Ichecked the themes with the original data and re-examined the thematic map to ascertain the robustness and uniformity of themes.

5.6.5.Phase fi ve

In this phase,with a detailed analysis,I de fi ned and further re fi ned the themes to ascertain the essence of each one that was relevant to the research questions.Following carefulconsideration, a succinct name was assigned to each theme.

Once thematic categories were created,the data were imported to a software program Nvivo,a popular and highly recognized software program for information management,reporting,and representation.It allows the researcher to categorize and store information as wellas create texturaland structuralpresentations, allowing for management of the information in an effective way. This allowed for rearranging and restructuring the themes to capture complex relationships and patterns.

5.6.6.Phase six

This phase involved writing a scholarly report to interpret the complex information ofthe fi eld texts and to presentthe fi ndings in a succinct and coherent account.

5.7.Narrative representations

Ire-wrote each theme using a three-dimensionalapproach,and represented the themes in a narrative format.I categorized each story in the sections,parts,or chapters ofmy reportthatelaborated on an essential aspect of the phenomenon of the research.Each heading,named the theme that is being described in that section, and complex phenomena were further subdivided in subsuming themes.22,36,56,57

In narrative representations,Ijoined the themes by representing them in the style ofnarratives/stories.The created stories were narrative representations,an explanation of the phenomenon in my research.As Clandinin31explained,‘the creation of the story itself may be considered an act of narrative analysis’.

When Ire-wrote my participants'stories in such a way to sustain the originaland express coherence through time,my narrative inquiry was a lived experience.Iwas notonly collecting fi eld texts,I was presenting the shared stories in a way that preserved the integrity of the told experiences.Clandinin and Connelly22emphasized that the research text in narrative inquiry should be an‘adequate’and‘authentic’narrative.Irespected and honored my participants'voices and stories as a narrative researcher.Iwas also aware of Bruner's58comments regarding the relationship of memory and imagination.He says,‘Through narrative,we construct,reconstruct,in some ways reinvent yesterday and tomorrow…The human mind… can never fully and faithfully recapture the past,but neither can it escape from it’.58

Instead of a frequency count or coding of selected terms as sometimes occurs in‘thematic analysis’,interpreting the meaning of the lived experience is a process of insightful discovery,as‘the notion of theme may best be understood by explaining its methodological and philosophical character’.36I listened to audio recordings multiple times,read and re-read transcriptions and other fi eld texts multiple times,and analyzed and tried to understand the meaning of the fi eld texts according to the research questions.Ithen collaborated with the participants by checking and negotiating the meaning oftheir stories.Drafts ofeach participant's story were sent to each participant for veri fi cation and feedback. When the veri fi cation and feedback were collected,the stories were revised according to their suggestions and comments.This member-checking phase of interpretation was the core of my research because it gave direct access to the participants'interpretation of their stories.Imarked notes,categorized the data by themes using thematic analysis procedures,and then re-storied using the three-dimensional approach that most accurately conveyed the research participants'meaning.40The participants' quotes were present within the fi ndings because the participant voice is centralto the telling.Lemley and Mitchell26suggested‘the richness of detail in the participants’quotations conveys identity more powerfully than any interpretation.Placing the participant as the primary teller allows the reader to interpret the participant's story instead of a researcher's interpretation’.26

In the process oftelling and retelling stories,in the metaphorical three-dimensional inquiry space of narrative inquiry,my participants and I moved backward and forward,inward and outward through time,from the personalto the social,shifting situation and place.Within this three-dimensionalinquiry space,as the contents of our stories were woven alongside each other,continuity and resonance shaped and reshaped our knowledge and understanding of our experiences.22

6.Conclusions

This paper has summarized the key philosophical,theoretical and methodological perspectives that underpinned the‘Chinese nursing students at Australian universities:a narrative inquiry into their motivation,learning experience,and future career planning’research project as wellas the issues around narrative inquiry and voice.

To enhance teaching and learning for internationalstudents and meet their speci fi c needs,it is important to understand their experiences and perceptions.There is no better way to achieve this than to let their voices be heard,letting them speak for and about themselves.Reality exists within the students,namely in their perceptions.When used with sensitivity and re flexivity,through the power ofstories,narrative inquiry as a research methodology offers a new dimension in international education research.Narrative inquiry gives a voice to students,enabling educators to hear and understand theircollective needs,which provides insights into how teaching and learning experiences can be improved for them.

Conflicts of interest

There is no con flict of interest.

1.Finney N,Rishbeth C.Engaging with marginalised groups in public open space research:the potential of collaboration and combined methods.Plan Theor Pract.2006;7:27e46.

2.De Souza R.Motherhood,migration and methodology:giving voice to the“other”.Qual Rep.2004;9:463e482.

3.Sokoloff NJ,Dupont I.Domestic violence at the intersections of race,class,and gender challenges and contributions to understanding violence against marginalized women in diverse communities.Violence Against Women. 2005;11:38e64.

4.Ashby C.Whose“voice”is it anyway?:Giving voice and qualitative research involving individuals that type to communicate.Disabil Stud Q.2011;31.

5.Wang CC,Geale S.The power of story:narrative inquiry as a methodology in nursing research.Int J Nurs Sci.2015;2:195e198.

6.Wang CC,Andre K,Greenwood KM.Chinese students studying at Australian universities with speci fi c reference to nursing students:a narrative literature review.Nurse Educ Today.2015;35:609e619.

7.Gubrium A.Digital storytelling:an emergent method for health promotion research and practice.Health Promot Pract.2009;10:186e191.

8.Hull GA,Katz ML.Crafting an agentive self:case studies of digital storytelling. Res Teach English.2006;41:43e81.

9.Ellis CS,Bochner A.Autoethnography,personal narrative,re flexivity: researcher as subject.In:The Handbook of Qualitative Research.London:Sage Publisher;2000.

10.Tuli F.The basis of distinction between qualitative and quantitative research in social science:re flection on ontological,epistemological and methodological perspectives.Ethiop J Educ Sci.2011;6:97e108.

11.Wang CC.Chinese Nursing Students at Australian Universities:A Narrative Inquiry into Their Motivation,Learning Experience,and Future Career Planning.Edith Cowan University;2017.

12.Dall WH,Boas F.Museums of ethnology and their classi fi cation.Science. 1887;9:612e614.

13.Locke A.The concept of race as applied to social culture.Howard Rev.1924;1: 290e299.

14.Glazer M.Cultural Relativism.McAllen:Texas;2011.

15.Mutch C.Doing Educational Research:A Practitioner's Guide to Getting Started. Wellington,N.Z:NZCER Press;2005.

16.Maxwell JA.Qualitative Research Design:An Interactive Approach.Thousand Oaks:SAGE Publications;2013.

17.Lincoln YS,Lynham SA,Guba EG.Paradigmatic controversies,contradictions, and emerging con fluences,revisited.In:The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research.4.2011:97e128.

18.Merriam SB.Case Study Research in Education:A Qualitative Approach.San Francisco:Jossey-Bass Publishers;1988.

19.Bogdan R,Biklen SK.Qualitative Research for Education.Allyn&Bacon;1997.

20.Barthes R,Duisit L.An introduction to the structural analysis of narrative.New Literary Hist.1975;6:237e272.

21.Singh S.Narrative and theory:formalism's recurrent return.Br Yearb Int Law. 2014;84:304e343.

22.Clandinin DJ,Connelly FM.Narrative Inquiry:Experience and Story in Qualitative Research.San Francisco:Jossey-Bass Publishers;2000.

23.Greene M.Releasing the Imagination:Essays on Education,the Arts,and Social Change.San Francisco:Jossey-Bass Publishers;1995.

24.Yolton JW.John Locke&Education.New York:Random House;1971.

25.Guba EG,Lincoln YS.Competing paradigms in qualitative research.In:Handbook of Qualitative Research.1994:2.

26.Lemley CK,Mitchell RW.Narrative Inquiry:Stories Lived,Stories Told 1ed.Chichester:Wiley;2011.

27.Chou MJ,Tu YC,Huang KP.Confucianism and character education:a Chinese view.J Soc Sci.2013;9:59e66.

28.Trahar S.Using narrative inquiry as a research method:an introduction to using critical event narrative analysis in research on learning and teaching by leonard webster,and patricie mertova.Compare J Comp Educ.2008;38: 367e368.

29.Yvonna Guba EG.Naturalistic Inquiry.Los Angeles:Sage Publications;1985.

30.Ulin PR,Robinson ET,Tolley EE.Qualitative Methods in Public Health:A Field Guide for Applied Research.John Wiley&Sons;2012.

31.Clandinin DJ.Handbook of Narrative Inquiry:Mapping a Methodology.Thousand Oaks,Calif:Sage Publications;2007.

32.Woolhouse RS.The Empiricists.USA:Oxford University Press;1988.

33.Hunter SV.Analysing and representing narrative data:the long and winding road.Curr Narratives.2010;1:44e54.

34.McMillan S,Price MA.Through the looking glass:our autoethnographic journey through research mind-fi elds.Qual Inq.2010;16:140e147.

35.Pinnegar S,Daynes JG.Locating narrative inquiry historically.Handbook of Narrative Inquiry:Mapping a Methodology.3e342007.

36.van Manen M.Researching Lived Experience:Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy.London,Ont:Althouse Press;1990.

37.Lopez KA,Willis DG.Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology:their contributions to nursing knowledge.Qual Health Res.2004;14:726e735.

38.Casey K.I Answer with My Life:Life Histories of Women Teachers Working for Social Change.New York:Routledge;1993.

39.Connelly FM,Clandinin DJ.Stories of experience and narrative inquiry.Educ Res.1990;19:2e14.

40.Creswell JW.Educational Research:Planning,Conducting,and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research.Upper Saddle River,N.J:Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall;2005.

41.Trahar S.Contextualising Narrative Inquiry:Developing Methodological Approaches for Local Contexts.Hoboken:Taylor and Francis;2013.

42.Riessman CK.Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences.Los Angeles:Sage Publications;2008.

43.Polkinghorne DE.Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences.Suny Press;1988.

44.Creswell JW.Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design:Choosing Among Five Traditions.Thousand Oaks,Calif:Sage Publications;1998.

45.Scollon R,Scollon SW,Jones RH.Intercultural Communication:A Discourse Approach.Malden,MA:Wiley-Blackwell;2012.

46.Auden WH.A short defense of poetry.In:Address given at a Round-table Conference on“Tradition and Innovation in Contemporary Literature”at the International PEN Conference in Budapest.1967:15.

47.Etherington K,Bridges N.Narrative case study research:on endings and six session reviews.Counselling Psychotherapy Res.2011;11:11e22.

48.Dewey J.Logic:The Theory of Inquiry.1938.The later works(1953),1e5491925.

49.Dewey J.Having an Experience.Art as Experience.New York,Minton:Balch& Co;1934:36e59.

50.Dewey J.Experience and Education.New York:Simon and Schuster;1938.

51.Xu Y,Davidhizar R.Intercultural communication in nursing education:when Asian students and American faculty converge.JNurs Educ.2005;44:209e215.

52.Ellis C.The Ethnographic I:A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Rowman Altamira;2004:196.

53.Braun V,Clarke V.Using thematic analysis in psychology.Qual Res Psych. 2006;3:77e101.

54.Glesne C.Becoming Qualitative Researchers:An Introduction.Boston,Mass: Pearson;2011.

55.Merriam SB.Qualitative Research:A Guide to Design and Implementation. Hoboken:Jossey-Bass Publisher;2014.

56.Creswell JW.Educational Research:Planning,Conducting,and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research.Upper Saddle River,N.J:Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall;2008.

57.Ollerenshaw JA,Creswell JW.Narrative research:a comparison of two restorying data analysis approaches.Qual Inq.2002;8:329e347.

58.Bruner JS.Making Stories:Law,Literature,Life.London:Harvard University Press;2003.

How to cite this article:Wang CC.Conversation with presence: A narrative inquiry into the learning experience of Chinese students studying nursing at Australian universities.Chin Nurs Res. 2017;4:43e50.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cnre.2017.03.002

20 June 2016

E-mail address:c.wang@ecu.edu.au.

Peer review under responsibility of Shanxi Medical Periodical Press.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cnre.2017.03.002

2095-7718/©2017 Shanxi MedicalPeriodical Press.Publishing services by Elsevier B.V.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Received in revised form 14 September 2016

Accepted 25 December 2016

Available online 30 March 2017

杂志排行

Frontiers of Nursing的其它文章

- Prevalence and associated factors of health problems among Indonesian farmers*

- Burnout and work-family con flict among nurses during the preparation for reevaluation of a grade A tertiary hospital

- Comparative research on the prognostic ability of improved early warning and APACHE II evaluation for hospitalized patients in the emergency department*

- Training indicators and quantitative criteria for emergency nurse specialists*

- Changing trends and in fluencing factors of the quality of life of chemotherapy patients with breast cancer*

- The application of the necessity-concerns framework in investigating adherence and beliefs about immunosuppressive medication among Chinese liver transplant recipients*