童道明:戏剧,是对另一种生活的渴望

2017-07-05张婷ZhangTing译曹宇光CaoYuguang

文张婷 Zhang Ting译曹宇光Cao Yuguang

童道明:戏剧,是对另一种生活的渴望

Tong Daoming: Theatre, Aspiration for a Different Kind of Life

文张婷 Zhang Ting译曹宇光Cao Yuguang

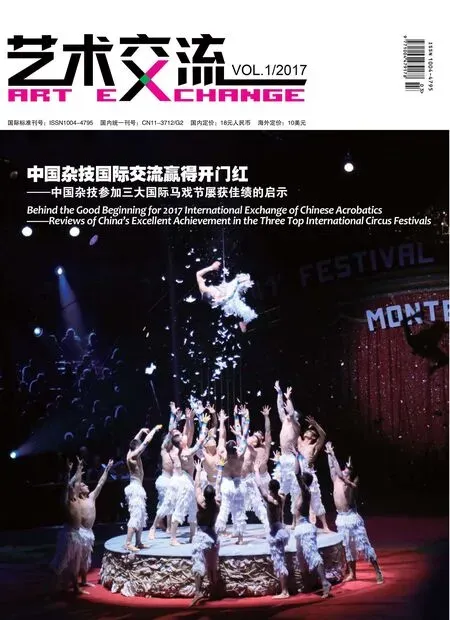

《三滴水》剧照Stage Photo of Three Drops of Water

提到“童道明”这个名字,很多人的第一印象都是著名的戏剧评论家、俄罗斯文学研究者,而在不久前的第七届南锣鼓巷戏剧节中,一出体量不大、舞台简朴更未有知名演员出演的《三滴水》,却收获了很多观众的好评;人们更惊奇地发现,写下这一作品的,正是如今已79岁的童道明。

1956年,19岁的童道明考入莫斯科大学,邂逅戏剧、亦邂逅影响他一生研究与创作的契诃夫;而60年后的今天,距离完成第一部剧本也已经10年,他仍旧笔耕不辍——“我的戏未见得是有多好,但我想让人们看到,戏还可以是这样的。”在社科院专家宿舍楼一间简朴的屋中,谈起自己写的戏,童道明如是说。

《三滴水》由《幽默是烫出来的》《我没有来晚吧?》与《风来雾散》三个喜剧小品组成,之所以取名“三滴水”,源于俄罗斯剧作家罗佐夫的《四滴水》。“罗佐夫把四个情节并不相关的故事放在一起,每个故事都像一滴水,能以小见大,反映一点什么。我也写了几个小品,想把它们放在一起。”童道明直言,“我们现在的小品大多是搞笑的,而我希望追求的是幽默,是能令人会心一笑的。”

没有常见于时下小品中的网络段子,没有刻薄的讽刺;有的只是微妙、细品之下更觉温暖的一连串日常中的趣事与微妙的情感。《风来雾散》的故事发生在文学期刊的编辑部里,演出现场,当剧中的女编辑在与诗歌作者沟通,朗诵起马雅可夫斯基的诗歌《好》时,笔者留意到,身边上了年纪的观众也在台下轻声背诵。“我记得当年留学时,问起我的俄罗斯同学最近过得怎么样,他就用了这首诗中的一句回答我——‘生活很好,生活得很好’。”在作品中多次出现诗歌,是童道明创作的一个特点,对此他谈到:“写着写着,会觉得戏剧与诗歌是更接近的。我的第四个剧本《歌声从哪里来》,里面的主人公是一位诗歌爱好者;而当我写到第六个剧本《一双眼睛两条河》时,主角是一位诗人,我就为剧中这位诗人写诗。我对契诃夫也一直有这样的感觉,他的戏剧比小说更接近于诗,在他的戏剧中,人物的台词离我们的现实生活是有距离,是有诗意的。这是写剧让我很愉快的原因——可以从现实生活中跳出来,做一种诗意的表达。”

说到契诃夫,童道明讲起1959年,自己在莫斯科大学文学系读三年级时,要写一篇题为《论契诃夫戏剧的现实主义象征》的学年论文。他的老师拉克申让他去列宁图书馆,将所有有关契诃夫的书目写在卡片上。“我将卡片做好后,他逐一看过,告诉我哪本需要细读,哪本不需要读,哪本只需要读其中的第几章。拉克申老师只比我年长4岁,但他对契诃夫有如此精到的了解,让我吃惊,更感到敬佩。1959年还是中苏关系的蜜月期,论文写完后,拉克申老师告诉我:‘童,我给你的论文打优秀,不是因为你是中国人。’当时他给我的评语是,一篇独立思考的论文,写得饶有趣味。当我准备回国的时候,他说,‘童,我希望你今后都不要放弃对戏剧、对契诃夫的兴趣’。这句话,影响了我的一生。”

“在俄罗斯念书的时候,一张学生票就相当于在学生食堂吃一顿午饭的价格,非常便宜。那段时间我看了很多戏,不只是契诃夫的,还有莎士比亚等剧作家的。”童道明讲到,“记得有一次去看《哈姆雷特》,坐在我前面是我们学校资历最深的一位院士。看他的样子就知道,他肯定不是第一回看这个戏了。为了反复欣赏自己喜欢的作品,甚至跟我们这些穷学生一起坐在很靠后的位置,这让我记忆犹新。”在童道明看来,俄罗斯之所以是戏剧大国,一个重要的原因在于那里有了不起的观众。

1990年,莫斯科艺术剧院总导演叶甫列莫夫受著名表演艺术家于是之的邀请,为北京人艺排演契诃夫的名剧《海鸥》,当时与童道明有过不少接触。“他非常奇怪,刚到北京就问我,中国有没有戏剧博物馆?我说,天津有一个,北京大概只有梅兰芳故居。他居然什么名胜古迹都没有去,就专门去了天津的戏剧博物馆和梅兰芳故居。”

莫斯科艺术剧院由斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基和丹钦科在1898年创建,而叶甫列莫夫版的《海鸥》抛开斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基的导演大纲,给出了仅有一个亭子在移动的假定性舞台,创新可谓大胆。“我记得他说:‘如果我现在还照搬斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基,那就意味着对斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基的背叛’。”童道明说,让他印象深刻的还有,叶甫列莫夫对《海鸥》主题的总结——对另一种生活的渴望。“我写的第一个剧本《我是海鸥》,也正是这样的一个主题。男女主人公都有对另一种生活的渴望,但两个人的渴望是不一样的。1996年是契诃夫的《海鸥》问世100周年,我完成了这个剧本,但写完就搁在那里了。”

“我写戏很大的动力,来自于是之的一句话。他探望病重的英若诚回来时对我说,最大的遗憾,是中国的舞台上少有真正为知识分子说话的戏。于是我下定决心要写知识分子,第二个剧本《塞纳河少女的面模》,就写的是我一直敬重的老所长、诗人冯至,写完也没有发表。”直到2009年9月17日,冯至先生诞辰100周年的那天,这部作品才被第一次搬上舞台,在蓬蒿剧场演出。

从《我是海鸥》到《塞纳河少女的面模》,再到《秋天的忧郁》《歌声从哪里来》《蓦然回首》……78岁时,童道明完成了自己的第十个剧本——《神圣的战争》。没有反面人物,是他作品的另一特点。说到这点,他还讲起一件挺有意思的事:有位上海戏剧学院戏文系的学生来看他,说“童老师,如果你的剧本是我们写的,在老师那里是通不过的”。“后来我想明白他说的是什么了,就是戏剧冲突不够尖锐,因为没有反面人物。”在童道明看来,这个创作上的“欠缺”亦是受契诃夫的影响,“他的剧本里都没有反面人物,当我自己开始写剧本之后,才能够体会为什么是这样的。善良的契诃夫,具有强烈的悲悯情怀,写不出坏人来。他不着力于写人与人之间的冲突,也因此开辟了一个新的戏剧种类。”童道明说,“戏剧好比一个女人,她有娘家——文学,也有婆家——舞台艺术;但随着导演中心制的流行,现在戏剧的文学性正在减弱。戏剧的文学性,不是具有强烈戏剧冲突的故事,也不是华丽的辞藻,而应该是展现人的精神生活和内心世界。”

独立思考,饶有趣味——求学时,恩师拉克申的评语,多年来被童道明谨记在心,并视作努力的方向。而他在创作《契诃夫和米奇诺娃》时,更巧借剧中角色“契诃夫”之口,说出了这样一段台词——“我刚刚写完一篇小说,我就把小说里的一段话念出来,送给你和你的朋友们:‘将自己的全部生命贡献给一项事业,从而让自己成为一个有情趣的人,也成为一个能让有情趣的人喜欢的人’。”

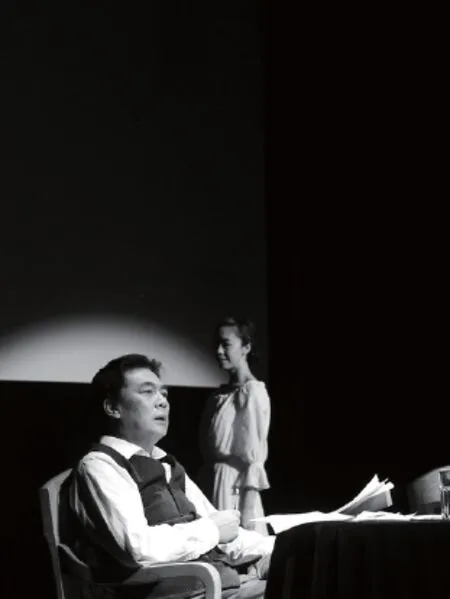

话剧《爱恋·契诃夫》剧照 王雨晨摄影Stage Photo of the Drama Affection in Love—Chekhov Taken by Wang Yuchen

话剧《塞纳河少女的面模》剧照Stage Photo of Face Mold of a Girl by Seine River

话剧《爱恋·契诃夫》剧照 王雨晨摄影Stage Photo of the Drama Affection in Love—Chekhov Taken by Wang Yuchen

When talking about Tong Daoming, many people will mention his first impression as a well-known theatre critic and researcher of Russian literature. However, in the 7th Beijing Nanluoguxiang Performing Arts Festival lately, a drama titled Three Drops of Water with a moderate plot, simple stage and ordinary cast was well-received by many audiences who surprisingly found that its author was just Tong Daoming, a senior citizen at the age of 79.

In 1956, Tong, at the age of 19, was admitted into Moscow University where he encountered theatre and Anton Chekhov, both of which have determined his lifelong research and creation. Today, after 60 years have passed by and a decade since his virgin script, he has never ceased his writing. “My plays are not necessarily perfect, but I would like to remind people that drama can be realized in my way.” Tong said when talking about his own works in a simple room of Experts’ Dorm at Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS).

The play Three Drops of Water consists of three comedies namely Humor is Boiled, Am I Late? and Wind Dismisses Fog. Its title is obviously a tribute to the play Four Drops of Water by Russian playwright Viktor Rozov. “Rozov just gathered four irrelevant stories, but every story, like a drop of water, did reflect a significant truth. Likewise, I wrote some tiny stories and piece them together.” Tong frankly uttered, “Though currently most comedies are just for laughs, I prefer to present humor that enables audiences to give a thought after laughing.”

In Tong’s play, we can find neither popular web-jokes nor mean satire. Instead, a series of daily interesting things and subtle feelings in his play will make audiences feel cozy in deep appreciation. The story of Wind Dismisses Fog is set in an editorial office of a literary magazine, and in the communications with poetry authors, the female editor recited some lines of the poem Good by Mayakovsky on live. At that moment, we can easily find that some elderly audiences couldn’t help reciting this familiar poem as well. “I still remember that when I asked one of my Russian fellow students how he was during my overseas study, he would invariably answer with a line of this poem—‘life is good, and I live a good life.’” The frequent occurrence of poetry is a significant characteristic of Tong’s plays. His explanation is as follows: “During my writing, I’ve come to realize that theatre is quite similar to poetry. In my fourth play Where Comes the Singing, the hero was a fan of poetry while in my sixth play A Pair of Eyes and Two Rivers the hero was a poet whose poetry was actually mine. I share this feeling about Anton Chekhov whose play, in contrast with his fiction, was much closer to poetry. In his play, the roles’ lines are of poetic sense and therefore keep a distance from our reality. That’s also why I enjoy composing plays—I can jump out of real life for a poetic expression”.

Upon Anton Chekhov, Tong mentioned his semester thesis titled On the Symbol of Realism in Chekhov’s Theatre when he was a junior student at Literature Department of Moscow University in 1959. Lakshin, his tutor, told him to collect all the references about Checkhov in Lenin Library and write down their names on a card. “When I completed that card, he looked through it very carefully and marked which book to read intensively, which to ignore and which to read a certain chapter only. Though he was merely four years older, his sophisticated knowledge about Chekhov indeed surprised me and aroused my admiration. The year 1959 was still within the honeymoon between China and Soviet Union. After I completed my thesis, Lakshin said to me, ‘Tong, I decide to give A to your thesis, but not because you come from China.’ As his comment said, ‘it is an essay with independent thinking and full of interesting ideas’. Before I set off back home, he said in all sincerity, ‘Tong, I hope that you will never give up interest in theatre or Chekhov’, which has influenced my entire life.” Tong recalled.

“During my study in Russia, a student’s admission was quite cheap, only at the mere price of a lunch at the canteen. At that time, I watched many plays, not only of Chekhov, but also other dramatists’ such as Shakespeare.” Tong said, “Once when I watched the play Hamlet, I found that an academician of the highest seniority was sitting in the front row of mine. From his facial expression, I could tell that he must have watched this play for several times. In order to appreciate his favorite play once and again,he never minded taking such a back seat with a group of poor students like me, which has impressed on my mind for good.” As far as Tong is concerned, as a great power of theatre, Russia is always blessed with many such extraordinary audiences as that figure.

In 1990, at the invitation of Chinese well-known performing artist Yu Shizhi, Oleg Efremov, the chief director of Moscow Art Theatre came to rehearse the Chekhov’s masterpiece The Seagull for Beijing People’s Art Theatre, and thus had quite a few contacts with Tong. "He was a queer guy, and upon his arrival in Beijing, he asked me if there was any theatre museum in China. I told him that there was one in Tianjin and in Beijing, the former residence of Master Mei Lanfang could be regarded as one. Then he paid a special visit to the theatre museum in Tianjian and Mei’s residence rather than any other places of tourist interest" .

The Moscow Art Theatre was established by Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko in 1898. However, the Efremov’s version of The Seagull had nothing at all to do with the Stanislavski’s director outline and showed bold innovation by presenting a moving pavilion as presumptive stage. “I still remember his following words, ‘if I totally copy Stanislavski’s version, that is nothing but betrayal of this theatre master.’” Tong recalled. What impressed him most was Efremov’s conclusion about the theme of the play—aspiration for a different kind of life. “My first play I’m a Seagull shared the same theme, and the hero and the heroine have their respective aspirations for a different kind of life, though the contents of their aspirations vary. The year 1996 was the 100th anniversary of the publication of Chekhov’s The Seagull and I completed my script in the same year, but there is no more follow-up.”

“My motivation for theatre creation comes from a meaningful word from Yu Shizhi who returned from a visit to Ying Ruocheng in severe illness—the biggest regret on China’s stage is lack of plays that speak for the intellectual. At this word, I was determined to choose Chinese intellectual as the hero of my following plays. My second play Face Mold of a Girl by Seine River is about Feng Zhi, a poet and elder head of Foreign Language Institute of CASS who I always respect. I just left it alone after completion.” Tong said. It was on September 17, 2009, the 100th anniversary of Master Feng Zhi’s birth that this play was presented on the stage of Penghao Theatre for the very first time.

From I’m Seagull to Face Mold of a Girl by Seine River, then to Autumn’s Melancholy, Where Comes the Singing and Total Retrospect, at the age of 78, Tong completed his 10th play Holy War. The absence of antagonist is another characteristic of his works. For this point, Tong told us an interesting story. A student from Department of Dramatic Literature of Shanghai Theatre Academy once came to see him and said,“Mr. Tong, supposing your play is our assignment, our teacher will never give it a pass.” “Later I came to realize that his point was that there is no antagonist in my play and therefore the dramatic conflict is not sharp enough.” As far as Tong can see, this flaw is also the outcome of Chekhov’s influence. “There is no antagonist either in Chekhov’s scripts and it was not until I began to compose my own script that I came to realize the reason. As a kind-hearted writer with a strong compassion, Chekhov was unable to present a bad guy. He never intended for an interpersonal conflict and thus opened up a new category in drama.”Tong said, “Just like a married woman, theatre has her own mother—literature and her own motherin-law—stage arts. Nevertheless, along with the fashion of director-core system, the literary feature of theatre is considerably reduced. Rather than a story with an intense dramatic conflict or florid rhetoric, the literary feature of a play ought to be a showcase of a person’s spiritual life and inner world.”

Such comments from his teacher Lakshin during his days in Russia as “independent thinking”, “full of interesting ideas” still linger in Tong’s mind as his direction for endeavor. When he composed the play Chekhov and Mizinova, he made a conclusion through the following line of the hero (Chekhov): “I’ve just completed a novel and I would like to quote a sentence from it as souvenir for you and your friends—‘by dedicating my entire life to a certain cause, I have turned myself into a person of good taste and a person favored by those of good taste’”.