第四章:老汉口特有的茶馆文化

2017-07-03

第四章:老汉口特有的茶馆文化

Chapter 4:The Unique Tea House Culture of Old Hankou

老汉口的茶馆始于何年,尚无从查考。但在老汉口人的印象中,汉口茶馆却有着特殊的记忆。很多市民每天做完事,都会到茶馆聊天、乘凉或者看戏、听评书。茶馆是市民聚会最方便且最适宜的地方。

There is no frame of reference for which year tea houses started cropping up in Old Hankou, but tea houses get many old-timers in Hankou waxing nostalgic. Tea houses are a part of these people’s daily routine. After work, many locals can be spotted in tea houses, chatting, enjoying the cool refreshing atmosphere, watching opera or listening to storytellers telling historical or traditional anecdotes. Tea houses are the most convenient and comfortable places to gather.

▲老汉口茶馆生意兴隆,茶客盈门 Customers filling the tea house in old Hankou

▲茶叶担夫 Polebearers carrying tea

19世纪初,范锴(清朝嘉道年间人士)在《汉口丛谈》有载:“后湖之有茶肆,相传自湖心亭始,近若涌金泉、第五家、翠芗、惠芳、习习亭、丽春轩之名为著,皆在下路雷祖殿、三元殿后。其余尚有数十处。”

另有资料显示:到宣统元年(1909),汉口的茶馆多达250家,占武汉三镇茶馆的60%。张之洞督鄂后,伴随工商业的迅猛发展,汉口的人口日益增加,茶馆生意更为兴旺。1931年武汉大水后,百业萧条,大批失业者涌入茶馆,茶馆生意格外兴隆。1933年,茶馆竟增至1373家。

这些茶楼中,较著名的有接驾嘴心怡茶楼,生成里口的味春茶馆,民生路口的话雅茶楼,永安市场的汉天春茶楼,后花楼街的德意茶馆,江汉路上的洞天居茶楼,以玩雀鸟著称的临城茶馆等等。

汉口茶馆以规模划分,25张茶桌以上算是一等,15~25张茶桌的为二等,5~10张桌子的系三等,5桌以下的属四等。

大茶馆大都集中于闹市区,其茶客多是工商圈内人物;中小茶馆则遍及街头巷陌,茶客亦因地段而别;狭道小街上的茶馆,茶客往往是各类手工业者;沿江沿河及铁路边的茶馆,是水陆办货客商及码头装卸工人的休闲之所;而设在公园与游览地的茶馆,则是游客休憩处。

从1861年汉口开埠到1949年中华人民共和国成立,将近百年的岁月,汉口城市经历了各种各样的历史变迁:张之洞治鄂的短暂繁荣、辛亥革命的战火破坏与重建、沦陷区日本铁蹄的蹂躏,不可预测的水灾火灾。

这里有各地商人、政客、帮会、警察、普通市民、码头工人、妓女、江湖艺人……不同层次、不同类别的人往往都愿意选择茶馆作为他们进行交易、宣传思想、秘密政治、搜集信息、休闲娱乐、挡风避雨的地方。所以,近代汉口的茶馆在历史发展中,就形成了各种各样的层次、种类,为满足不同的人群需要;各种不同人群的自然选择,也形成了不同茶馆之间的特点和文化。

Early in the 19th century, Fan Kai, a man who lived during the period between the reign of Emperor Jia Qing and Dao Guang of the Qing Dynasty, recorded in The Collected Writings on Hankou,“Houhu District was said to have tea houses since the opening of Huxinting Tea House. The most recent popular ones, including Yongjinquan, Diwujia, Cuixiang, Huifang, Xixixuan and Lichunxuan, all sit roadside behind the Thunder God Temple and the Temple of the Gods of Heaven, Earth and Water. The remaining dozens are yet to be counted.”

Other information shows that tea houses in Hankou numbered as many as 250 by the year of 1909, beginning of Emperor Xuantong’s reign in the QingDynasty, accounting for 60% of the total tea houses at the three main boroughs of Wuhan. After Zhang Zhidong became governor of Hubei, the tea house business flourished right alongside the extraordinary development of commerce and industry in the area, meanwhile the population of Hankou increased. In 1931, unemployed workers flocked to tea houses en masse during an economic downturn that occurred in the wake of a terrible flood, yet the tea house business remained untouched by recession and was all the more prosperous. The number of tea houses increased to 1,373 by the year 1933.

The famous local tea houses included, Xinyi Tea House at Jie Jiazui, Weichun Tea House at Shengcheng Likou, Huaya Tea House at Minsheng Road, Hantianchun Tea House at Yong’an Market, Deyi Tea House at Houhualou Street, Dongtianju Tea House at Jianghan Road, and Lincheng Tea House, which was famous for its bird play.

Tea houses in Hankou were categorized by size: those with more than 25 tables are top tier, those with 15 to 25 tables are second tier, those with 5 to 10 tables are third tier, and those with fewer than five tables are forth ttiieerr..

Most of the big tea houses were clustered in the downtown area, and the majority of the patronss are members of the local business and industrial community. Medium and small tea houses were scatered here,there and everywhere, and those who frequent the smaller-scaallee joints were typically a diverse subset of the local craftsmen; the tea houses bordering the rivers, lakes and railroads were fun zones for local merchants and longshoremen, while tea houses in parkss or tourist sites were the rest stops for weary travelers.

Approximately 100 years have passed from 1861,the year when Hankou Port opened to world trade, and the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. During that time Hankou has gone through every conceivable historical transformation: from the short-lived renaissance of Zhang Zhidong era to the utter destruction brought on by Xinhai Revolution (in 1911) and the subsequent reconstruction to the devastation of the Japanese occupation, and to the unforeseeable floods and fires.

Tea houses here were frequented by business people, politicians, the underworld, policemen, urbanites, longshoremen, harlots, buskers; all types of people from every social stratum and walk of life made tea houses their preferred place for wheeling and dealing, conceiving promotional ideology, conducting hush-hush political deals, information gathering, recreation, or just simply taking shelter from the elements. Thus, the recent historical development has formed a Hankou tea house culture as unique and multifarious as the tea houses that serve it. The differing demands of different people naturally and gradually evolved the characteristics and culture of the tea house that matches his or her own particular style.

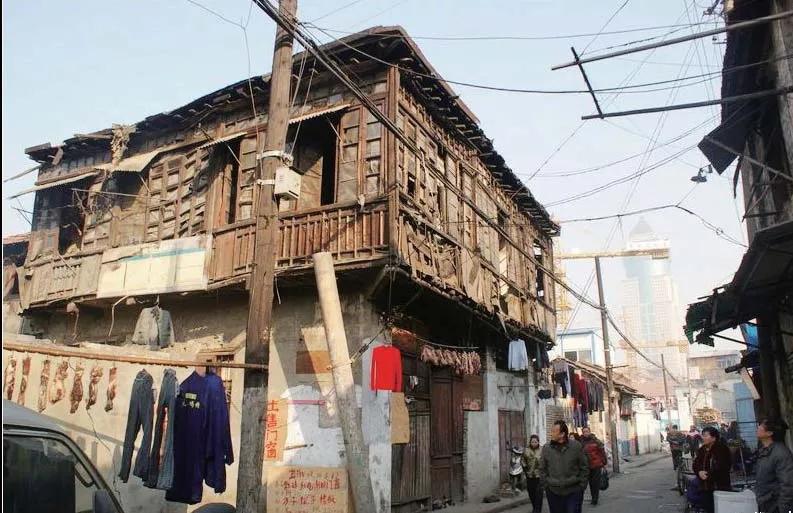

▲龄鹤茶馆旧址 Linghe Tea House before it was demolished

民国汉口的茶馆,分为“清水”和“浑水”两种。清水茶馆以卖茶为主,茶馆里不打牌不唱戏。“浑水茶馆”既卖茶,又有唱戏、卖曲、打牌、赌博及其他娱乐活动。这些都形成了汉口茶馆丰富的内涵。它并非一个静止的老房子,而是一种活生生的汉口人的生活和历史。

生活在不同城市阶层中的汉口人,对汉口的茶馆有着他们固执的爱好——

或许一位码头工人,做了一天的苦力,挣到一些微薄的工资,除去开销已经所剩无几。夜幕降临,繁星满天,热风吹拂,匆匆吃过晚饭后,他急忙忙赶到最近的一家简陋的茶馆。这里茶资便宜,而且晚间会有说书、小曲。虽然设备简陋,但看着是那样亲切。不一会儿,小小的茶馆就挤满了各式各样的茶客。他们是这个城市的底层人,穿着粗布衣服,品着廉价的茶水,全神贯注盯着前面台上的演出,可能是说书,也可能是江湖艺人的小曲演唱,或是杂耍、皮影戏,精彩的演出不时会引起满堂喝彩。

与此同时,在汉口的另外一些茶馆中却可能上演着另一种不同的生活。这里空间开阔、设施豪华、或有包间、上好的檀木桌椅,来这里喝茶的人出手阔绰,一掷千金。来这里喝茶,不仅仅是喝茶,讲的还是排场,京剧、汉剧、楚剧名角轮番上场。也许在某一个茶馆不为人注意的角落,一个秘密的政治计划正在筹备,或茶馆的阴暗处几双诡秘的眼睛正密切注视着茶馆中人的一举一动,以便得到有效的情报。

1938年武汉沦陷后,汉口茶馆业只残存有250家,从此一蹶不振,直到解放前,武汉三镇一共只有茶馆300余家。然而,直到如今,这些著名的不著名的茶馆大多已不复存在。

当地媒体《武汉晚报》曾刊登过一篇关于花楼街拆迁的文章。文章说:“花楼街103号,矗立着一栋暗红色雕栏窗户的老屋,这就是有着近百年历史的广益桥龄鹤茶馆旧址。”

如今,龄鹤茶馆旧址早已随着花楼街改造而被拆除。老汉口的茶馆仅剩下位于前进一路的鹤阳茶馆还保留至今。

鹤阳茶馆位于汉口民主一街与前进一路的西北转角处,是移动两层的砖混结构、红瓦楼房,临街二楼是现在已不多见的木结构阳台。它的二楼直到上世纪六十年代仍在经营茶馆。据说,湖北的第一个全国象棋冠军李义庭经常在这家茶馆下棋。

历经近百年的风风雨雨,老楼保存完好。据居住在这里的老汉口人介绍,这是一家“浑水”茶馆。每天,附近的居民都能听见楼上的锣鼓声,抬头看得见化了妆的演员。那时候,时断时续的楚戏的悲腔在夜晚的天空飘荡……

During the Republican Era (1911-1949), tea houses in Hankou were divided into two types,“pure” and “fusion.” The “pure” tea houses focused solely on tea drinking with no card games or opera performances. “Fusion” tea houses were not only for tea drinking, but also for enjoying operas, music, cards and other entertainment activities. These different types of tea houses enriched and enlivened Hankou tea houses. The tea house was not simply an old building in a static location but was imbued with the life and history of Hankou people.

Old Hankou’s varying social classes hold tenaciously to their own particular ways of passing the time at tea houses.

Perhaps a dockhand has worked his fingers to the bone for the whole day, earned his meager wage, and after factoring out his expenses, would not have two bucks to rub together. Yet as the night falls, as the twinkling stars fill the sky, as the night winds begin to blow, after wolfing down his supper he would still prefer to scurry over to the nearest shabby little tea house to pass the night away.

The tea is cheap and there is entertainment like storytelling and music. Though the décor at this type of tea house is not much to speak of, the atmosphere is nonetheless warm and cozy.

By and by, this tiny tea house is overflowing with customers from every stratum of the lower classes. Though dressed in two-bit attire and imbibing on low-grade tea, they are nevertheless engrossed in the performances which are, perhaps a book being read with great panache, or the impassioned song and dance of a local busker, or perhaps a heartpounding show of acrobatic prowess, or perhaps an enchanting performance of shadow puppet theater. Whatever it is, it’s sure to bring the house down.

Meanwhile, at other tea houses, there is another kind of life altogether being lived out on the other side of Hankou. The upscale tea houses have luxurious facilities and décor, expensive tables with chairs made of ebony, and private rooms. The customers are high rollers and spend money like water. They come not only for the tea but also to flaunt their wealth and social status while Peking opera, Han opera and Chu opera play in turn. Perhaps there is a secret political plan being devised in an obscure corner of some tea houses, or a pair or two of prying eyes peeping at the patrons from a shadowy area of some other tea house, trying to steal some intelligence.

During the Japanese occupation of Wuhan since 1938, the number of remaining tea house in Hankou were on the decline and fell to 250, with only 300 tea houses existing in the three boroughs of Wuhan all the way up to the time of the liberation. And even now, most of these tea houses do not exist anymore, regardless of whether they were once famous or not.

The local Wuhan Evening News once published an article about the demolition of Hualou Street, which mentioned there was an old building with dark red caved window at 103 Hualou Street. It was the former site of Linghe Tea House at Guangyi Qiao with nearly a century of history behind it.

Now, Linghe Tea House has been demolished, and the only old tea house left in Hankou is Heyang Tea House at No.1 Qianjin Road.

Heyang Tea House is located at the northwest corner of the intersection of Minzhu No. 1 road and Qianjin No.1 road in Hankou. It is a two-story brick building with a red tile roof. The second floor had a wooden balcony that can be rarely seen nowadays. It had operated as a tea house until the 1960s. It’s said that Li Yiting, the first national chess champion in Hubei, often played chess there.

The old building is still well preserved after nearly a century. People who have lived in the neighborhood for many years say it used to be a“fusion” tea house. Every day, people living nearby could hear the sound of gongs and drums and catch sight of actors in full costume inside the building. At that time, the melancholy strains of Chu opera could be heard from time to time during the night.

▲鹤阳茶馆 Heyang Tea House

俗话说,“下汉口,坐茶馆”。在汉口,茶馆生活已经成为人们生活中不可或缺的一部分,或者说成为汉口城市市民生活的一种方式。当年的茶客中曾流行不少“口头禅”,颇能反映昔年社会背景与民间风俗——

“不是光棍,不开茶馆”。开茶馆虽本小利大,但常有地痞流氓寻衅闹事,故茶馆老板必以青洪帮或军警宪特头目作后台。

“行时的酒馆,背时的茶馆”。行时即生意好,背时则指生意差。生意好做的时候,都上酒馆;不好做的时候,都泡茶馆。

“上午皮包水,下午水包皮”。有的茶客喜欢兼营澡堂的茶馆,尤其是隆冬,上午喝茶,下午泡澡堂。如此一天下来,既过了茶瘾,又驱寒取暖,好不惬意。当然,能这样悠闲的,多为有钱人家。

“前世打爷骂娘,今生落得跑堂,吃的是粗茶淡饭,睡的是八只脚的床”。茶馆伙计通称“茶房”或“跑堂”,工作不分白天黑夜,薪水微薄,伙食差,晚上无固定睡床,只好将两张茶桌拼拢当床。可叹他们还迷信“前世有过,今生报应”。

茶馆,无疑是一个“小社会”,它是老汉口的一个缩影。

As the saying goes, “When in Hankou, refresh yourself at a teahouse,” it is an indispensable part of Hankou residents’ lives. It’s a lifestyle choice for them. Back in the day, there were many popular“pet phrases” that spread among customers at tea houses, which quite appropriately reflect the social background and folk customs of the time.

“Do not run a tea house if you are not single.”Despite the fact that running a tea house was a low cost, high profit venture, many ruffians would come around looking for a fight, so the tea houses had to be backed by local triads or leaders of police or military.

“A tavern in bullish times, a tea house in bearish times.” Bullish times means business is good, bearish times means business is bad. While a busy tavern could satisfy people’s taste buds in times of prosperity, people would prefer staying at quiet tea houses to enjoy tea and tranquility in times of hardship. Therefore, tea houses were often popular in times of a down economy.

“In the morning skin surrounds water, in the afternoon water surrounds skin.” Essentially, this refers to drinking tea in the morning and taking a bath in the afternoon. This saying showed that some customers preferred a tea house equipped with a bathhouse, especially in cold winter. They could enjoy drinking tea in the morning and taking a bath in the afternoon. While it’s a fantastic way to relax, it’s only for the financially well endowed.

“Sinners in the previous life, would they become tea house servers in this life. Coarse and plain foods they eat in the day, eight-legged hard table bed they sleep on in the night.” Servers who work at tea houses were often called “cha fang” or “pao tang.” They work day and night with a little salary, eat simple foods and have no formal bed to sleep in. Instead, they would sleep on a “bed” of two tea tables moved together. What’s worse, superstitious as they were, they would always say, “What goes around, comes around,” and believe it to be their karma.

There is no doubt that the tea house is a “society in miniature,” and a microcosm of old Hankou.