Gemcitabine-based combination therapy compared with gemcitabine alone for advanced pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials

2017-06-19

Hangzhou, China

Gemcitabine-based combination therapy compared with gemcitabine alone for advanced pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials

Shui-Fang Jin, Zhao-Kun Fan, Lei Pan and Li-Ming Jin

Hangzhou, China

BACKGROUND: Pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive malignancies and chemotherapy is an effective strategy for advanced pancreatic cancer. Gemcitabine (GEM) is one of first-line agents. However, GEM-based combination therapy has shown promising efficacy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. This meta-analysis aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of GEM-based combination therapy versus GEM alone in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer.

DATA SOURCES: A comprehensive search of literature was performed using PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. A quantitative meta-analysis was performed based on the inclusion criteria from all eligible randomized controlled trials. The outcome indicators included overall survival (OS), 6-month survival, 1-year survival, progression-free survival/time-to-progression (PFS/TTP), and toxicities.

RESULTS: A total of nine randomized controlled trials involving 1661 patients were included in this meta-analysis. There was significant improvement in the GEM-based combination therapy with regard to the OS (HR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.76-0.95,P=0.003), PFS (HR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.65-0.90,P=0.002), 6-month survival (RR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.01-1.17,P=0.03), and the overall toxicity (RR=1.68, 95% CI: 1.52-1.86,P<0.01). However, there was no significant difference in the 1-year survival.

CONCLUSIONS: GEM-based combination chemotherapy might improve the OS, 6-month survival, and PFS in advanced pancreatic cancer. However, combined therapy also added toxicity.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2017;16:236-244)

gemcitabine; pancreatic cancer; chemotherapy; cisplatin; S-1; meta-analysis

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive malignancies, the fourth leading cause of cancerrelated death.[1,2]The National Cancer Institute reported that 39 590 patients died of pancreatic cancer in 2014 in the United States.[3]Because pancreatic cancer has no specific clinical manifestation including laboratory test and images, it is difficult to make early diagnosis. The majority of patients are in advanced stage of pancreatic cancer when diagnosed and 90% of the cancers are unresectable. The 5-year survival rate is less than 4%.[4]Most of the patients need treatments other than surgery. Chemotherapy is one of them. It is well documented that chemotherapy prolongs the survival time of patients with pancreatic cancer.[5,6]Up to now, many different chemotherapeutic drugs can be used to treat pancreatic cancer and patients can benefit from these treatments.[7-9]Therefore, chemotherapy plays a very important role in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. At present, gemcitabine (GEM) single-agent chemotherapy is one of the first-line drugs in advanced pancreatic cancer treatments.[10,11]There is currently no standard chemotherapeutic regimen worldwide. The chemotherapeutic failure of the first-line reagent may be due to reagent itself ortreatment plan. Therefore, identification of novel reagents and chemotherapeutic combinations is critical for improving the outcome and diminishing the side effects.

For further observation of GEM in the synergistic effect of chemotherapy, many researchers carried out GEM-based combination therapy trials, notably the united cisplatin and/or S-1 study.[11-13]Most clinical randomized controlled trials (RCT), according to the double medicine GEM combination chemotherapy effect, have achieved better efficacy than that of monotherapy. However, some RCTs indicated an adverse outcome. Whether the double medicine GEM combination chemotherapy is better than the single-reagent treatment is not clear. The present meta-analysis compared the efficacy and safety between double medicine GEM combination chemotherapy and single-agent chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer.

Methods

Literature search

A comprehensive search of literature was performed using PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The terms are: pancreas, pancreatic cancer, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, pancreatic neoplasms, gemzar, gemcitabine and GEM. Date of last search: May 30, 2016.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

All prospective, controlled, randomized studies published as originals or abstracts were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were: (1) pathologically confirmed advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic cancer; (2) baseline Karnofsky performance status score ≥50% and normal organ function; (3) double drugs on the basis of GEM combination chemotherapy and its comparison with single standard chemotherapy, the combination group adopts double medicine GEM combined scheme, GEM group used GEM only; and (4) without anti-tumor therapy (induding surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy) within 6 months before trial. And the exclusion criteria were: (1) without a full-text and non-published conference abstracts; (2) letters, reviews, commentaries, case reports, editorials; (3) non-RCT clinical trials. For duplicated literature reports, the most comprehensive ones were selected.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The literatures identified from the defined sources were assessed independently by two authors. The discrepancies between the two authors were resolved after discussing among all of the authors. If one author concluded an abstract to be eligible, the full-text of article was retrieved and reviewed in detail. Missing data from the original article was obtained from the investigators. If the same trial appeared on different publications, the final data of the trial was chosen. The following parameters were extracted: (1) first author’s name, the study type and year of publication; (2) patient characteristics, number of eligible patients, chemotherapy regimens, study design, and follow-ups; (3) treatment outcome, such as overall survival (OS), 6-month and 1-year survival rates, progression-free survival/time-to-progression (PFS/TTP) and toxicities. For response assessment, we used trials that included patients with measurable or assessable diseases, and that were analyzed mainly with WHO’s criteria. Toxicity pro files were reported according to the WHO’s criteria. All disputes and divergences were resolved through discussion. Statistician was consulted if necessary.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed with RevMan software (version 8.2, Cochrane). The primary end point included OS. The second end points included 6-month and 1-year survival rates, PFS/TTP, and side effects. TTP was de fined as the period from randomization to documented disease progression and PFS from randomization to disease progression. In almost all of the trials, patients recruited with relatively healthy status died of disease progression. PFS therefore in real practice is dif ficult to be separated from TTP and we did not speci fically separate them in analysis. All variables were de fined as dichotomous data (e.g., 6-month survival rate used variables as follows: the alive or dead at 6-month after randomization). We standardized the therapeutic results by obtaining the risk ratio (RR) between the GEM combination group and the GEM group. The hazard ratio (HR) with 95% con fidence intervals (CIs) was estimated directly or indirectly from the reported data. The OS and PFS were calculated2by HR in this study. The Chi-square basedQ-test andIstatistics test were used to assess heterogeneity of studies.[14]The random-effects model was used if there was heterogeneity between the studies; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. APvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically signi ficant.

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

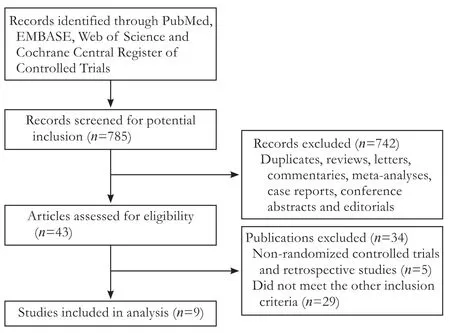

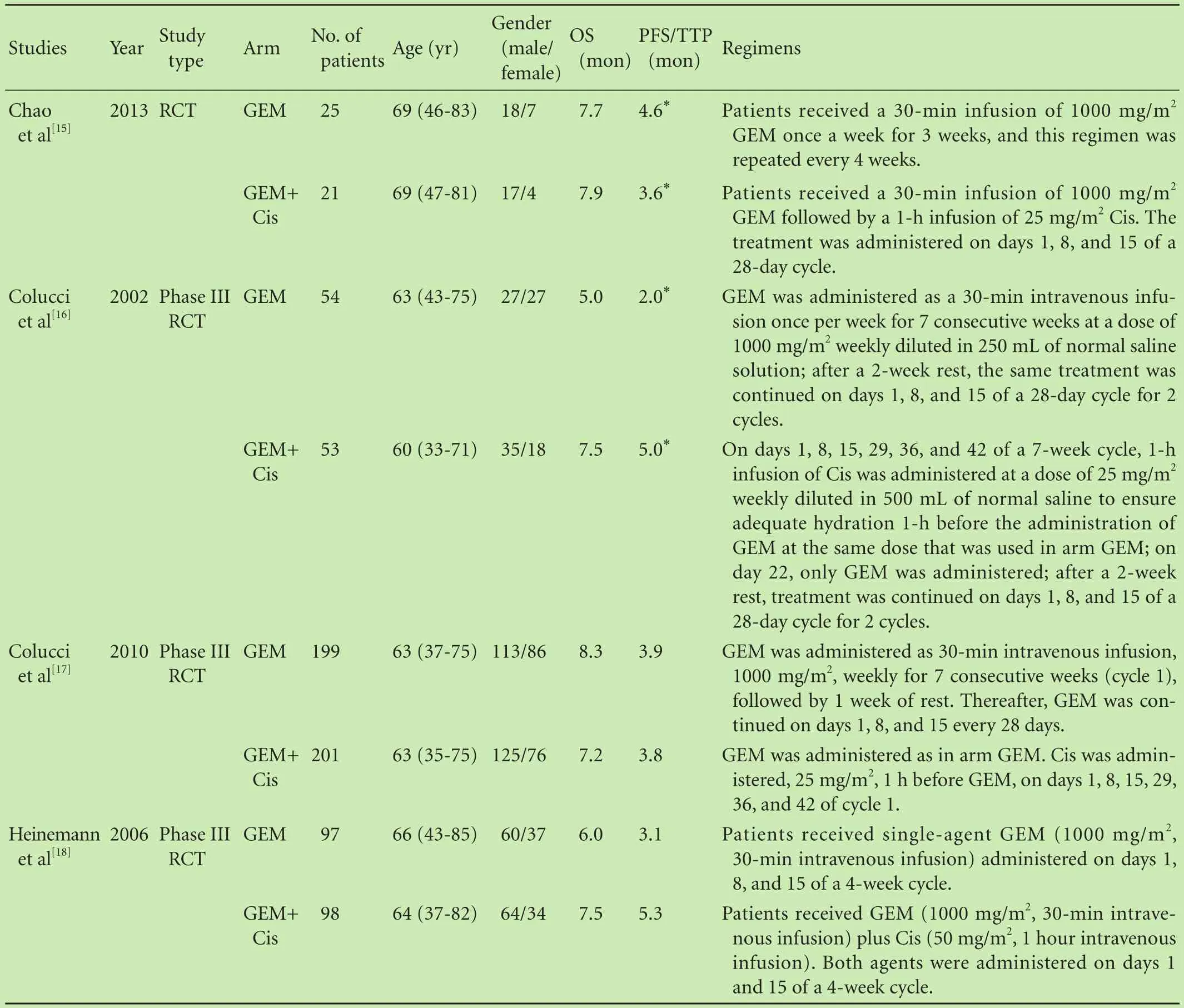

The flowchart of our study is shown in Fig. 1. Nine studies were eligible for this meta-analysis.[15-23]Characteristics of the 9 included studies are shown in Table. The 9 RCTs involving 1661 patients were analyzed. Among them, 827 patients were allocated to the GEM combina-tion group and 834 in the GEM group.

All selected trials were prospective, randomized and well designed, and the clinical characteristics were matched for age, gender, tumor stage, and study type. All patients were confirmed histologically or cytologically pancreatic cancer, with the same baseline data and without evidence of selection bias. Of the 9 trials, seven were randomized phase II/III trials. The 6-month and 1-year survival rates were extracted from 8 trials.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study selection procedure for included trials.

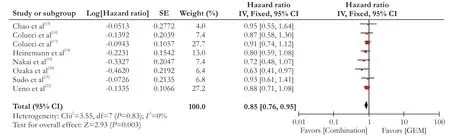

Overall survival

Nine studies reported the median overall survival. The hazard ratio (HR) of overall survival was calculated or acquired from eight RCTs. There was no heterogeneity in these studies (I2=0%,P=0.83), and a fixed-effectsmodel was employed for meta-analysis of HR. The HR was lower in the patients treated with GEM combination group than that with GEM alone group (P〈0.05). The GEM combination group had higher overall survival than the GEM alone group (HR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.76-0.95,P=0.003) (Fig. 2).

Table. Characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis

Table. Characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis

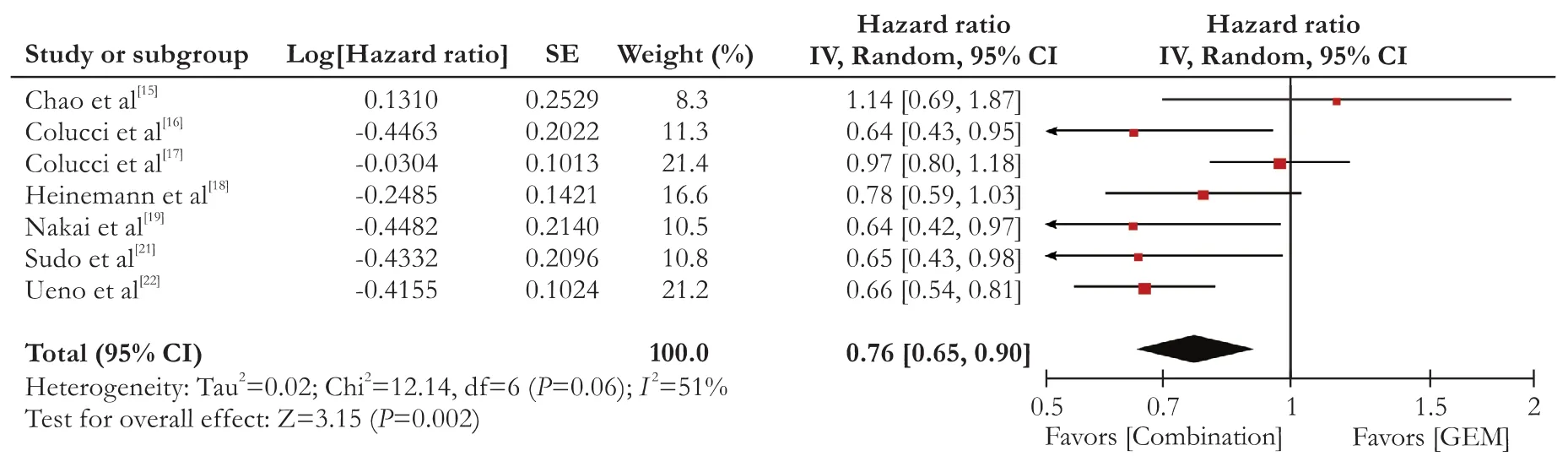

Progression-free survival

Seven trials reported the HR value of PFS. The patients from the seven studies were divided into two groups, GEM combination and GEM alone. The heterogeneity of the outcome of PFS between the two groups was significant (I2=51%,P=0.06). A random-effects model was adopted. The PFS in GEM combination group was higher than that in the GEM alone group. Overall, there was a significant increase of the PFS in GEM combination group compared with that in the GEM alone group (HR=0.76, 95% CI: 0.65-0.90,P=0.002). There was a signi ficant improvement (76%) in GEM combination group (Fig. 3).

Six-month and 1-year survival rates

After pooling the relevant 6-month survival data, no heterogeneity among the studies (I2=32%,P=0.17) was found; therefore, a fixed-effects model was employed for meta-analysis of RR. The overall meta-analysis revealed that RR was lower for the patients treated with GEM combination than that with GEM alone (RR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.01-1.17,P=0.03) (Fig. 4).

There was no statistically signi ficant inter-group difference that existed in the 1-year survival rate (RR=1.16; 95% CI: 0.91-1.49;P=0.23). And there was a small intergroup heterogeneity in the 1-year survival rate (I2=47%,P=0.07) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2. Forest plots of included studies between the GEM combination versus GEM groups in overall survival (OS).

Fig. 3. Forest plots of included studies between the GEM combination versus GEM groups in progression-free survival (PFS).

Fig. 4. Forest plots of included studies between the GEM combination versus GEM groups in 6-month survival rate.

Fig. 5. Forest plots of included studies between the GEM combination versus GEM groups in 1-year survival rate.

Toxicity

The grade 3/4 toxic effects of chemotherapy were summarized in Fig. 6. Main toxic effects were analyzed. Neutropenia (38.1%) was the most frequent grade 3/4 toxicity in both groups. As compared with GEM alone, GEM combination group signi ficantly increased the incidence of leukopenia (RR=1.88; 95% CI: 1.49-2.37;P〈0.01), neutropenia (RR=1.62; 95% CI: 1.41-1.87;P〈0.01), thrombocytopenia (RR=1.65; 95% CI: 1.25-2.20;P〈0.01), anemia (RR=1.41; 95% CI: 1.07-1.88;P〈0.05), nausea/ vomiting (RR=2.97; 95% CI: 1.85-4.75;P〈0.01) and diarrhea/constipation (RR=1.93; 95% CI: 1.07-3.46;P〈0.05), while showing no difference in the incidence of anorexia (RR=1.16; 95% CI: 0.75-1.81;P=0.51). After data pooling of the seven toxicities, we found that the GEM combination group had higher toxicity compared with that of GEM alone group (RR=1.68, 95% CI: 1.52-1.86,P〈0.01).

(To be continued)

Fig. 6. Forest plots of included studies between the GEM combination versus GEM groups in toxicities (grade 3/4).

Discussion

GEM is considered a basic chemotherapeutic reagent for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Based on the available evidence, GEM-based combination regimen may be promising in advanced pancreatic cancer.[24-26]National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines indicated that GEM improves the therapeutic effect in the GEM-based combination regimen.[27]

In this study, The PFS in advanced pancreatic cancer patients treated with GEM-based combination chemotherapy was significantly superior to that with GEM mono-chemotherapy in the first half year. These indicated that GEM-based combination chemotherapy of advanced pancreatic cancer can significantly improve the 6-month survival rate. However, GEM-based combination chemotherapy do not significantly improve the 1-year survival rate of patients. Similarly, Banu et al[28]also reported that combination chemotherapy could improve short-term (6-month) survival rate, not the 1-year survival rate. We speculated that the survival time of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer is short, once the patients are in the late-stage, the patient’s physical status deteriorates and the body’s sensitivity to chemotherapy drugs decreases, and even the resistance to chemotherapy also decreases.

The second end points of this analysis was side effects of chemotherapy. The data showed that GEM-based combination chemotherapy of advanced pancreatic cancer significantly increased the toxicity reaction, and it mainly manifested the toxicity in blood and digestive system. This result was also consistent with another meta-analysis.[29]Because of the effect of cytotoxicity of the platinum, we proposed that platinum drug is not suit-able for elder patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and poor physical situation. Therefore, GEM combined with cisplatin is more beneficial in patients with better physical situation.

One limitation of our meta-analysis is that the data were extracted from the English literature only. RCT published in other languages may cover a wider range of combination regimens. Heterogeneity among trials is another limitation. Although we applied a random-effects model that takes possible heterogeneity into consideration, there were still many factors causing heterogeneity, e.g., different drug combination, infusion methods.

In conclusion, GEM-based combination chemotherapy significantly improves 6-month survival rate and overall survival rate compared with GEM mono-chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, but increases the side effects as well. The chemotherapeutic effect on patients with advanced pancreatic cancer not only depends on the therapeutic plan, but also on the patient’s health status, such as physiological condition and laboratory data. Pros and cons, the more effective drug or drug combination might also have worse side effects. The survival rate at the end may be not that different. We should rationally individualize the chemotherapeutic regimen for patient with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Contributors:JSF and JLM performed the research and wrote the first draft. JSF, FZK and PL collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. JLM is the guarantor.

Funding:This study was supported by grants from the Scientific Research Foundation of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Zhejiang Province (2015ZA081), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY14H030006), Foundation for Young Scientists of Zhejiang Province Traditional Chinese Medicine (2011ZQ008), and the Health and Family Planning Committee of Zhejiang Province (2012KYB143).

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:277-300.

2 Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2013. Ann Oncol 2013;24:792-800.

3 Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9-29.

4 Kamisawa T, Wood LD, Itoi T, Takaori K. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2016;388:73-85.

5 Squadroni M, Fazio N. Chemotherapy in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010;14:386-394.

6 Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:1073-1081.

7 Reni M, Cereda S, Rognone A, Belli C, Ghidini M, Longoni S, et al. A randomized phase II trial of two different 4-drug combinations in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: cisplatin, capecitabine, gemcitabine plus either epirubicin or docetaxel (PEXG or PDXG regimen). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:115-123.

8 Ghaneh P, Smith R, Tudor-Smith C, Raraty M, Neoptolemos JP. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant strategies for pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008;34:297-305.

9 Katz MH, Fleming JB, Lee JE, Pisters PW. Current status of adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Oncologist 2010;15:1205-1213.

10 Petrelli F, Coinu A, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, Barni S. Progression-free survival as surrogate endpoint in advanced pancreatic cancer: meta-analysis of 30 randomized first-line trials. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2015;14:124-131.

11 Heinemann V. Gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer: a comparative analysis of randomized trials. Semin Oncol 2002;29:9-16.

12 Cao C, Kuang M, Xu W, Zhang X, Chen J, Tang C. Gemcitabine plus S-1: a hopeful frontline treatment for Asian patients with unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2015;45:1122-1130.

13 Inal A, Kos FT, Algin E, Yildiz R, Dikiltas M, Unek IT, et al. Gemcitabine alone versus combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of multicenter study. Neoplasma 2012;59:297-301.

14 Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539-1558.

15 Chao Y, Wu CY, Wang JP, Lee RC, Lee WP, Li CP. A randomized controlled trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus gemcitabine alone in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2013;72:637-642.

16 Colucci G, Giuliani F, Gebbia V, Biglietto M, Rabitti P, Uomo G, et al. Gemcitabine alone or with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective, randomized phase III study of the Gruppo Oncologia dell’Italia Meridionale. Cancer 2002;94:902-910.

17 Colucci G, Labianca R, Di Costanzo F, Gebbia V, Cartenì G, Massidda B, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with single-agent gemcitabine as firstline treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: the GIP-1 study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1645-1651.

18 Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schönekös H, Rost A, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3946-3952.

19 Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, Tsujino T, Toda N, et al. A multicentre randomised phase II trial of gemcitabine alone vs gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer: GEMSAP study. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1934-1939.

20 Ozaka M, Matsumura Y, Ishii H, Omuro Y, Itoi T, Mouri H, et al. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1combination versus gemcitabine alone in the treatment of unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer (Japan Clinical Cancer Research Organization PC-01 study). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:1197-1204.

21 Sudo K, Ishihara T, Hirata N, Ozawa F, Ohshima T, Azemoto R, et al. Randomized controlled study of gemcitabine plus S-1 combination chemotherapy versus gemcitabine for unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2014;73:389-396.

22 Ueno H, Ioka T, Ikeda M, Ohkawa S, Yanagimoto H, Boku N, et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1640-1648.

23 Wang X, Ni Q, Jin M, Li Z, Wu Y, Zhao Y, et al. Gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus cisplatin for in 42 patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2002;24:404-407.

24 Spadi R, Brusa F, Ponzetti A, Chiappino I, Birocco N, Ciuffreda L, et al. Current therapeutic strategies for advanced pancreatic cancer: A review for clinicians. World J Clin Oncol 2016;7:27-43.

25 Hess V, Pratsch S, Potthast S, Lee L, Winterhalder R, Widmer L, et al. Combining gemcitabine, oxaliplatin and capecitabine (GEMOXEL) for patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma (APC): a phase I/II trial. Ann Oncol 2010;21:2390-2395.

26 Rougier P, Riess H, Manges R, Karasek P, Humblet Y, Barone C, et al. Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallelgroup phase III study evaluating aflibercept in patients receiving first-line treatment with gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:2633-2642.

27 Zhao YP. Interpretation of the Chinese edition of NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Guideline 2011. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2011;49:771-773.

28 Banu E, Banu A, Fodor A, Landi B, Rougier P, Chatellier G, et al. Meta-analysis of randomised trials comparing gemcitabinebased doublets versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Drugs Aging 2007;24:865-879.

29 Ciliberto D, Botta C, Correale P, Rossi M, Caraglia M, Tassone P, et al. Role of gemcitabine-based combination therapy in the management of advanced pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:593-603.

July 26, 2016

Accepted after revision February 16, 2017

Author Affiliations: Intensive Care Unit (Jin SF and Fan ZK) and Department of Oncology (Pan L), First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou 310006, China; Department of General Surgery, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, Hangzhou 310014, China (Jin LM)

Li-Ming Jin, MD, Department of General Surgery, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, Hangzhou 310014, China (Tel: +86-571-85893418; Email: hz_jlm@163.com)

© 2017, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(17)60022-5

Published online May 23, 2017.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Patients with early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma have poor prognosis

- Combined cavo-atrial thrombectomy and hepatectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Traditional surgical planning of liver surgery is modified by 3D interactive quantitative surgical planning approach: a single-center experience with 305 patients

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International

- Crosstalk of liver immune cells and cell death mechanisms in different murine models of liver injury and its clinical relevance

- Circulating autoantibodies to endogenous erythropoietin are associated with chronic hepatitis C virus infection-related anemia