青岛近海路氏双髻鲨群体遗传学分析

2017-05-16娜王航宁刘淑德涂忠高天翔

宋 娜王航宁刘淑德涂 忠高天翔

(1. 中国海洋大学水产学院, 青岛 266003; 2. 乳山市水产技术推广站, 乳山 264500; 3. 山东省水生生物资源养护管理中心, 烟台 264003)

青岛近海路氏双髻鲨群体遗传学分析

宋 娜1王航宁2刘淑德3涂 忠3高天翔1

(1. 中国海洋大学水产学院, 青岛 266003; 2. 乳山市水产技术推广站, 乳山 264500; 3. 山东省水生生物资源养护管理中心, 烟台 264003)

研究采集了青岛近海23尾路氏双髻鲨(Sphyrna lewini), 通过线粒体DNA控制区片段对其遗传多样性进行分析。研究结果显示: 在23个个体的控制区序列上存在13个变异位点, 未检测到插入/缺失位点; 检测到7个单倍型, 其中3个为个体共享单倍型(Hap1、Hap3和Hap5), 4个为个体独有单倍型; 青岛近海路氏双髻鲨呈现中等水平的单倍型多样度和较低的核苷酸多样度; 与已报道的日照、霞浦群体间的遗传分化指数Fst值分别为–0.0571和–0.0328, 表明青岛群体与其他两个群体间不存在显著差异。以Sphyrna zygaena为外群构建NJ系统树显示本研究中7个单倍型共分成两支, 分别与来自太平洋、印度洋的单倍型类群聚类。中国近海的路氏双髻鲨作为一个具有较低遗传多样性的濒危物种, 其资源保护更应该引起足够的重视。

路氏双髻鲨; 遗传多样性; 濒危物种; 资源保护

路氏双髻鲨(学名: Sphyrna lewini; 英文名: the scalloped hammerhead shark)是双髻鲨属(Sphyrna)中一种全球性热带和暖温带水域分布的鲨鱼[1,2],分类上隶属于真鲨目(Carcharhiniformes)、双髻鲨科(Sphyrnidae)。双髻鲨因具有特殊横向延伸的头部而得名, 路氏双髻鲨是其中体型较大的种类, 其生性凶猛, 喜食小型鱼类, 繁殖方式为胎生, 一次可产下15至31尾幼鲨。与其他类型海洋鱼类相比较,鲨鱼因生长缓慢、性成熟时间长等特点限制了其自我补充能力[3—5], 这使得鲨鱼极易受到过度捕捞的影响。鲨鱼具有较高的经济价值和药用价值, 所以一直以来都是商业和休闲渔业的重要捕捞对象。据报道近年来鲨鱼的资源都已经遭到不同程度的破坏[6,7], 路氏双髻鲨资源量也大大减少[8], 已被世界自然保护联盟(IUCN)列为濒危物种, 2013年被收录至《濒危野生动植物种国际贸易公约(CITES)》的附录Ⅱ中。

海洋鱼类在其地理分布范围内通常呈现出较弱的遗传分化, 这主要是由于地理群体间缺少交流障碍以及其较强的扩散能力所致[9—11], 对鲨鱼、金枪鱼等具有较强运动能力的海洋鱼类来说更是如此。但近年来大量的群体遗传学研究发现如栖息地的不连续分布、海洋鱼类的底栖生活习性等都可以成为阻碍海洋鱼类基因交流的障碍[12,13]。鲨鱼繁殖方式一般为产沉性卵或者胎生, 其生活史特征中缺乏能够促进基因交流的卵和仔鱼的浮游期,且鲨鱼会在固定的近海水域进行产卵[14,15], 存在恋出生地(Philopatry)行为, 这些生活史特性可能会阻碍鲨鱼群体间的基因交流, 从而使不同群体间产生遗传分化[16,17]。路氏双髻鲨为胎生鱼类, 因此同样缺乏卵和仔鱼的浮游期, 其季节性聚集行为也暗示其可能存在恋出生地行为[18—21], 暗示其种群间可能存在基因交流的障碍。

到目前为止, 线粒体DNA控制区因其具有较高的种内多态性成为研究群体水平遗传多样性的理想标记, 黑梢真鲨Carcharhinus limbatus[17,22]等多种鲨鱼线粒体DNA的研究都显示其种群内存在显著的遗传结构。国外学者对路氏双髻鲨已有较多的研究[18,23,24], 群体遗传结构也有研究报道[25,26]。例如, Nance等[25]采用微卫星标记以及线粒体DNA测序两种方法分析了东太平洋6个地点的路氏双髻鲨样品, 结果显示其种群内不存在显著的遗传结构。Duncan等[26]分析了来自太平洋、印度洋和大西洋的路氏双髻鲨样品, 结果显示同海区沿岸分布的群体之间有很强的基因交流, 但是三个大洋间群体遗传差异显著。国内关于路氏双髻鲨的研究较少[27,28], 尚未见关于青岛近海路氏双髻鲨群体遗传学的研究报道。本研究采用线粒体DNA控制区部分序列测定对青岛近海的23尾路氏双髻鲨进行分析, 阐明青岛近海路氏双髻鲨群体的遗传多样性现状, 以期为我国近海路氏双髻鲨的种群分布和基因交流现状提供证据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 样品采集

于2012年9月在山东青岛沿海采集到23尾路氏双髻鲨样品(体长59.0—69.0 cm; 体重977.3—1669.1 g), 经形态鉴定后, 将样品冷冻保存至中国海洋大学渔业生态学实验室, 并取背部肌肉于95%的酒精中保存。

1.2 DNA提取

采用传统酚-氯仿方法提取路氏双髻鲨基因组DNA, 用超纯水将乙醇沉淀后的DNA溶解, –20℃保存备用。

1.3 PCR扩增与产物测序

采用引物Pro-L和SLcr-H[25]扩增控制区第一高变区。PCR反应体系为25 μL (基因组DNA约为10 ng、正反向引物各200 nmol/L、Taq DNA聚合酶1.25单位、200 μmol/L的每种dNTP、50 mmol/L KCl、1.5 mmol/L MgCl2和10 mmol/L Tris)。PCR反应均在TaKaRa热循环仪上完成, 反应循环参数参照宋娜等[28]。设阴性对照来检测PCR是否存在污染。取2 μL PCR产物用1.5%的琼脂糖凝胶进行检测, 回收纯化的目的片段送上海桑尼生物科技有限公司进行双向测序。

1.4 数据分析

从GenBank下载了日照和霞浦两个群体的序列(序列号为KU942394-KU942398)以及Ducan等报道的25个单倍型(序列号为DQ438148-DQ43817)用于比较分析。将本研究测得序列用Lasergene软件包中Seqman软件进行比对, 对测序胶图进行核对并辅以人工校正; 与GenBank中的序列比对后截取同源序列进行分析; 序列的碱基组成、变异位点、转换/颠换值以及群体遗传分化指数Fst、确切P检验采用Arlequin3.11软件包进行分析; 采用jModeltest软件计算反映突变速率在不同位点间异质性的gamma分布形状参数。基于AICc准则, 筛选出适合序列分析的模型为HKY+I+G (G=0.7010)[29], 基于HKY+ I+G模型, 以Sphyrna zygaena (序列号GU385314)为外群, 使用PAUP 4.0软件构建单倍型的邻接树(Neighbor joining, NJ)[30], 采用1000次非参数自展分析进行重复检验计算系统树各分支的置信度[31]。采用Arlequin 3.11软件来进行中性假说检验以及核苷酸不配对分布分析[32,33]。

2 结果

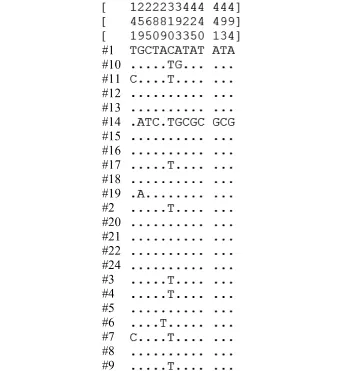

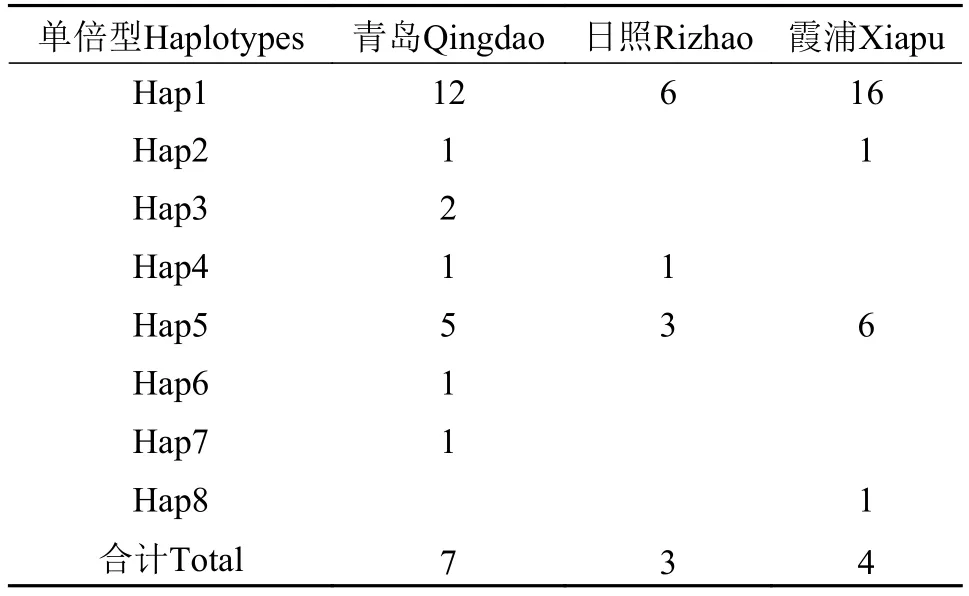

将获得的序列经过人工比对校正, 得到长度681 bp的控制区序列, 与GenBank中的序列进行比对后截取548 bp同源片段序列进行分析。在本研究中, 青岛群体的序列碱基含量分别为C: 23.14%、T: 37.08%、A: 31.17%、G: 8.60%, A+T碱基含量(68.3%)明显大于C+G含量(31.7%)。青岛群体的控制区序列上共存在13处核苷酸替换(12个转换和1个颠换), 未检测到插入/缺失位点(图 1), 共定义了7个单倍型, 其中3个单倍型为个体共享单倍型(Hap1、Hap3和Hap5), 其余4个单倍型为个体独有单倍型(表 1)。与日照和霞浦两个群体的序列比对后, 共获得8个单倍型, 其中4个单倍型为群体共享单倍型(Hap1、Hap2、Hap4和Hap5), 其余4个单倍型为群体独有单倍型。在本研究中, 青岛群体的单倍型多样度(Haplotype diversity)、核苷酸多样度(Nucleotide diversity)、两两序列比较的平均碱基差异数(The mean number of pairwise nucleotide dif-ferences)分别为0.6957±0.0880、0.0034±0.0023和1.8658±1.1080。

图 1 路氏双髻鲨青岛群体控制区序列变异位点Fig. 1 Variable sites of S. lewini from Qingdao based on mitochondrial control region sequences

青岛群体与日照、霞浦群体间的遗传分化指数Fst值分别为–0.0571和–0.0328(表 2), 两两群体之间的遗传差异较小且统计检验结果均不显著, 表明青岛群体与其他两个群体间不存在显著差异。确切P检验的结果也均不显著(表 2), 表明青岛群体与其他两个群体存在随机交配现象。

以Sphyrna zygaena为外群, 构建了青岛、日照、霞浦3个群体8个单倍型和Ducan等25个单倍型的NJ系统树。结果显示存在4个显著分化的单倍型类群, 其中来自大西洋的隐存种(DQ438148)形成单独一支, 中国近海路氏双髻鲨8个单倍型分别与来自太平洋、印度洋的单倍型类群聚类(Clade A、Clade C)聚为两支, 而在单倍型分支B (Clade B, 大西洋、印度-西太平洋)中未检测到中国近海的单倍型分布(图 2)。

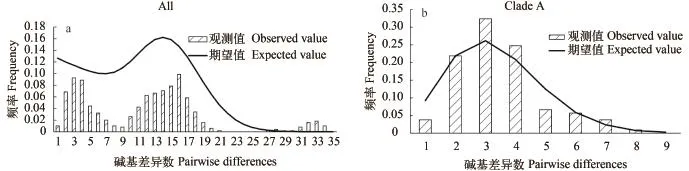

在本研究中, 路氏双髻鲨的核苷酸不配对分布图呈多峰类型(图 3a), 而个体数较多的单倍型分支A的核苷酸不配对分布呈明显的单峰状态(图 3b),暗示其可能经历过近期的群体扩张事件。分支A的Tajima’D检验结果并未显著偏离中性(Tajima’s D=–1.302, P=0.095), 但Fu’Fs检验结果却是显著的(Fs=–6.857, P=0.001), 这可能是由于Fu’Fs检验对近期群体扩张更为敏感所致。对观测值和模拟值的拟合度进行检验结果显示, 观测值与期望值非常吻合(Harpending’s指数=0.01, P>0.05), 没有显著偏离扩张模型[34]。基于单倍型类群A的τ值2.387和0.8%/ Myr的分歧速率计算显示路氏双髻鲨群体扩张事件大约发生在540kyr前。

表 1 路氏双髻鲨3个群体的单倍型频率分布表Tab. 1 Haplotype distribution of three S. lewini populations

表 2 路氏双髻鲨两两群体间的遗传分化指数Fst(对角线下)和确切P检验(对角线上)Tab. 2 Pairwise Fst(below diagonal) and the significant nondifferentiation exact P test value (above diagonal) among three populations of S. lewini

图 2 基于路氏双髻鲨线粒体控制区单倍型构建的邻接关系树Fig. 2 Nj tree for S. lewini control region haplotypes以Sphyrna zygaena为外群构建系统树,分支上的数字表示支持率, 支持率<60%的未列出Sphyrna zygaena was used to root the tree as an outgroup. Bootstrap with <60% were unshown

3 讨论

鲨鱼通常处于食物链的顶端, 因此在生态系统中具有十分重要的作用。路氏双髻鲨是为数不多的近海常见且数量较多的鲨鱼之一, 是近海鲨鱼捕捞业的重要渔获对象, 因此承受了巨大的捕捞压力,同时路氏双髻鲨的集群行为使其更易受到商业捕捞的影响。根据NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service)[35]报道, 有些海域的路氏双髻鲨资源已经处于过度捕捞状态。本研究中青岛近海路氏双髻鲨呈现中等水平的单倍型多样度和较低的核苷酸多样度, 与日照、霞浦两群体的遗传多样性水平(h=0.51±0.01—0.60±0.13; π=0.0024±0.0017—0.0046±0.0031)相当[28], 与太平洋东海岸与西海岸的路氏双髻鲨群体遗传多样性指数也相近[26]。较低的遗传多样性在其他一些受威胁的鲨鱼中也有报道, 例如Mustelus schmitti[36]、Negaprion brevirostris和N. acutidens[37]等。

图 3 路氏双髻鲨线粒体控制区核苷酸不配对分布图Fig. 3 The mismatch distributions for the control region haplotypes in S. lewinia. 所有样品; b. 分支A (柱形为观测值; 曲线为群体扩张模型下的预期分布)a. all samples; b. Clade A (Bars: observed pairwise differences; solid line: the expected mismatch distributions under the sudden expansion model)

群体间遗传分化指数计算结果表明中国近海路氏双髻鲨3个群体间不存在显著的遗传分化, 确切P检验的结果暗示群体间可能存在频繁的基因交流, 虽然路氏双髻鲨大洋间存在显著的遗传差异,但是沿海岸线分布的群体间并不缺乏基因交流[26]。路氏双髻鲨的系统地理格局类型与许多全球性分布的软骨鱼类相似, 如Carcharhinus limbutus[17,18]、Lagenorhynchus obscurus[38]等。基因交流可以维持物种的遗传多样性[39], 但是本研究结果暗示路氏双髻鲨较低的遗传多样性可能并不是有限的基因交流导致的, 这一结果提示其资源状况可能并不乐观。为保持物种对环境的适应能力, 其有效群体大小以及群体遗传多样性都应该维持在某一水平[39]。对路氏双髻鲨的历史动态研究结果表明其有效种群与过去相比明显减小[24], 过度捕捞可能降低了有效种群大小[40], 使种群更易发生遗传漂变进而降低遗传多样性[41]。

NJ树中中国近海的8个单倍型分别与来自太平洋、印度洋单倍型聚类, 且不与地理位置相对应,而大西洋和印度-西太平洋的单倍型单独构成分支。Ducan等[26]认为巴拿马海峡的封闭导致了大西洋群体的隔离, 而印度-西太平洋的单倍型是大西洋群体从西向东扩散的结果, 夏威夷或者南非的群岛可能是路氏双髻鲨进入东太平洋的基石。复杂的动态历史导致了路氏双髻鲨单倍型类群的分化。印度-太平洋与大西洋间历史上的隔离是许多海洋生物存在类似系统地理格局的主要因素, 如Thunnus obesus[42]、Lagenorhynchus obscurus[38]等。

许多沿大陆架海域分布的鲨鱼移动能力较弱,通常只在沿海区域活动, 并不向大洋扩散[43,44]。Kohler和Turner[45]对路氏双髻鲨进行标志放流研究, 结果显示标记点与回捕点的距离一般不超过100 km,且很少在开阔海域捕到路氏双髻鲨, 但是有一个个体移动距离甚至超过了1600 km。因此这种鲨鱼一般不进行长距离扩散, 但偶然也有跨大洋运动的行为[41]。因此尽管不能确定路氏双髻鲨是否存在恋出生地行为, 但是考虑到路氏双髻鲨沿岸分布以及很少长距离扩散的特性, 如果某一海域的路氏双髻鲨资源严重破坏, 将很难从其他海域进行补充, 因此禁止过度捕捞以及对路氏双髻鲨的保护是十分重要的。作为一个遗传多样性较低的濒危物种, 路氏双髻鲨资源保护管理更应该引起足够的重视。

[1]Zhu Y D, Zhang C L, Cheng Q T, et al. Fishes of East China Sea [M]. Beijing: Science Press. 1963, 286—293 [朱元鼎, 张春霖, 成庆泰, 等. 东海鱼类志. 北京:科学出版社. 1963, 286—293]

[2]Compagno L, Dando M, Fowler S. A field Guide to the Sharks of the World [M]. Harper-Collins, London. 2005, 368

[3]Musick J, Burgess G, Cailliet G, et al. Management of sharks and their relatives (Elasmobranchii) [J]. Fisheries, 2000, 25(3): 9—13

[4]Tsai W P, Liu K M, Joung S J. Demographic analysis of the pelagic thresher shark, Alopias pelagicus, in the northwestern Pacific using a stochastic stage-based model [J]. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2010, 61(9): 1056—1066

[5]Tillett B J, Meekan M G, Field IC, et al. Similar life history traits in bull (Carcharhinus leucas) and pig-eye (C. amboinensis) sharks [J]. Marine and Freshwater Research, 2011, 62(7): 850—860

[6]Ferretti F, Worm B, Britten G L, et al. Patterns and eco-system consequences of shark declines in the ocean [J]. Ecology Letters, 2010, 13(8): 1055—1071

[7]Baum J, Myers R. Shifting baselines and the decline of pelagic sharks in the Gulf of Mexico [J]. Ecology Letters, 2004, 7(7): 135—145

[8]Hayes C G, Jiao Y, Cortexs E. Stock assessment of scalloped hammerheads in the western North Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico [J]. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 2009, 29(5): 1406—1417

[9]Palumbi S R. Genetic divergence, reproductive isolation, and marine speciation [J]. Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics, 1994, 25(1): 547—572

[10]Graves J E. Molecular insights into the population structure of cosmopolitan marine fishes [J]. Journal of Heredity, 1998, 89(5): 427—437

[11]Heist E J, Musick J A, Graves J E. Genetic population structure of the shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) inferred from restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of mitochondrial DNA [J]. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 1996, 53(3): 583—588

[12]Grant W S, Waples R S. Spatial and temporal scales of genetic variability in marine and anadromous species: implications for fisheries oceanography. In: Harrison P, Parsons T R (Eds.), Fisheries Oceanography: an Integrative Approach to Fisheries Ecology and Management [M]. Blackwell Science Ltd, Oxford. 2000, 61—93

[13]Waples R S, Gustafson R G, Weitkramp L A, et al. Characterizing diversity in salmon from the Pacific Northwest [J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2001, 59(Supplement sA): 1—41

[14]Springer S. Social Organization of Shark Populations. In: Gilbert P W, Matheswon R F, Rall D P (Eds.), Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 1967, 149—174

[15]Lund R. Chondrichthyan life history styles as revealed by the 320 million years old Mississippian of Montana [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1990, 27(1): 1—19

[16]Hueter R E. Philopatry, natal homing and localised stock depletion in sharks [J]. Shark News, 1998, 12:1—2

[17]Keeney D, Heist E. Worldwide phylogeography of the blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus) inferred from mitochondrial DNA reveals isolation of western Atlantic populations coupled with recent Pacific dispersal [J]. Molecular Ecology, 2006, 15(12): 3669—3679

[18]Klimley A P, Nelson D R. Schooling of the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini, in the Gulf of California [J]. Fishery Bulletin, 1981, 79(2): 356—360

[19]Compagno L J V. FAO Species Catalogue. Vol. 4. Parts 1 & 2, Sharks of the world [M]. FAO Fisheries Synopsis. 1984

[20]Castro J I. The shark nursery of Bulls Bay, South Carolina, with a review of the shark nurseries of the southeastern coast of the United States [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1993, 38(1—3): 37—48

[21]Simpfendorfer C A, Milward N E. Utilization of a tropical bay as a nursery area by sharks of the families Carcharhinidae and Sphyrnidae [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1993, 37(4), 337—345

[22]Keeney D, Heupel M, Hueter R, et al. Genetic heterogeneity among blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, continental nurseries along the US Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico [J]. Marine Biology, 2003, 143(6): 1039—1046

[23]Steven B. Age, growth and reproductive biology of the silky shark, Carcharhinus falciformis and the scalloped hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini, from the northwestern Gulf of Mexico [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1987, 19(3): 161—173

[24]Klimley A P. Highly directional swimming by scalloped hammerhead sharks, Sphyrna lewini, and subsurface irradiance, temperature, bathymetry, and geomagnetic field [J]. Marine Biology, 1993, 117(1): 1—22

[25]Nance H A, Klimley P, Galván-Magaña F, et al. Demographic processes underlying subtle patterns of population structure in the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini [J]. PloS One, 2011, 6 (7): e21459

[26]Duncan K M, Martin A P, Bowen B W, et al. Global phylogeography of the scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) [J]. Molecular Ecology, 2006, 15 (8): 2239—2251

[27]Chen P M, Li Y Z, Yuan W W. Demographic analysis of scalloped hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini [J]. South Chinese Fisheries Science, 2006, 2(4): 15—19 [陈丕茂, 李永振,袁蔚文. 路氏双髻鲨的种群统计分析. 南方水产, 2006, 2(4): 15—19]

[28]Song N, Gao T X, Wang Z Y. Comparative analysis based on the mitochondrial DNA control region of Sphyrna lewini [J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2012, 36(8): 1153—1157 [宋娜, 高天翔, 王志勇. 中国近海路氏双髻鲨群体线粒体DNA控制区序列比较分析. 水产学报, 2012, 36(8): 1153—1157]

[29]Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating of the humanape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA [J]. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 1985, 22(2): 160—174

[30]Swofford D L. PAUP* Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4 [M]. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 2002

[31]Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on a phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap [J]. Evolution, 1985, 39(4): 783—791

[32]Ray N, Currat M, Excoffier L. Intra-deme molecular diversity in spatially expanding populations [J]. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2003, 20(1): 76—86

[33]Excoffier L. Patterns of DNA sequence diversity and genetic structure after a range expansion: lessons from the infinite-island model [J]. Molecular Ecology, 2004, 13(4): 853—864

[34]Harpending R C. Signature of ancient population growth in a low-resolution mitochondrial DNA mismatch distribution [J]. Human Biology, 1994, 66(4): 591—600

[35]NMFS. U.S. national plan of action for the conservation and management of sharks [R]. U.S. Dept. Comm., NOAA/NMFS, Silver Spring, Md, 2001, 1—3

[36]Pereyra S, Garcia G, Miller P, et al. Low genetic diversity and population structure of the narrownose shark (Mustelus schmitti) [J]. Fisheries Research, 2010, 106(3): 468—473

[37]Schultz J K, Feldheim K A, Gruber S H, et al. Global phylogeography and seascape genetics of the lemon sharks (genus Negaprion) [J]. Molecular Ecology, 2008, 17(24): 5336—5348

[38]Cassens I, Van Waerebeek K, Best P B et al. Evidence for male dispersal along the coasts but no migration in pelagic waters in dusky dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obscurus) [J]. Molecular Ecology, 2005, 14(1): 107—121

[39]Reed D H, Frankham R. Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity [J]. Conservation Biology, 2003, 17: 230—237

[40]Hauser L, Adcock G J, Smith P J, et al. Loss of microsatellite diversity and low effective population size in an overexploited population of New Zealand snapper (Pagrus auratus) [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 2002, 99(18):11742—11747

[41]Allendorf F, Luikart G. Conservation and the genetics of populations. Okford: Blackwell Publishing. 2007

[42]Chow S, Okamoto H, Miyabe N, et al. Genetic divergence between Atlantic and Indo-Pacific stocks of bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) and admixture around South Africa [J]. Molecular Ecology, 2000, 9(2): 221—227

[43]Musick J A, Harbin M M, Compagno L J V. Historical zoo-geography of the Selachii [M]. In: Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives In: Carrier J C, Musick J A, Heithaus M R (Eds.), CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. 2004, 33—78

[44]Kohler N E, Casey J G, Turner P A. NMFS cooperative shark tagging program, 1962—93: an atlas of shark tag and recapture data [J]. Marine Fisheries Review, 1998, 60(2): 1—87

[45]Kohler N E, Turner P A. Shark tagging: a review of conventional methods and studies [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 2001, 60(1-3): 191—224

GENETIC STUDY ON SPHYRNA LEWINI FROM QINGDAO COASTAL WATERS

SONG Na1, WANG Hang-Ning2, LIU Shu-De3, TU Zhong3and GAO Tian-Xiang1

(1. Fisheries College, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China; 2. Rushan Fishery Technology Popularization Center, Rushan 264500, China; 3. Shandong Hydrobios Resources Conservation and Management Center, Yantai 264003, China)

The scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini, is a small to medium-sized shark that circumglobally distributes along continental margins and oceanic islands in tropical waters. It has been listed as one globally endangered species by IUCN because of continuous resource recession by habitat degradation and influence of human activities. The present study analyzed mitochondrial DNA sequences of a total of 23 specimens collected from Qingdao coastal waters, and found 13 variable sites in the 548 bp fragments without indel/deletion. These polymorphic sites defined 7 haplotypes, 3 of them (Hap1, Hap3 and Hap5) were different individuals and the other 4 haplotypes were unique for one individual. Moderate haplotype diversity and low nucleotide diversity were detected for Qd population. There was no genetic differentiation between Qd and other reported two populations, and Fstwere –0.0571 and –0.0328, respectively. Haplotypes from Chinese coastal waters were clustered into two clades with haplotypes from the Pacific and Indian Ocean by the topology of the NJ tree rooted with the out-group S. zygaena. More attentions should be paid to resource protection for Sphyrna lewini with, and the endangered species (Sphyrna lewini) from Chinese coastal waters should be considered one population, which need greater resource protection because of low genetic diversity.

Sphyrna lewini; Genetic diversity; Endangered species; Resource protection

Q346+.5

A

1000-3207(2017)03-0603-06

10.7541/2017.77

2016-06-22;

2016-11-07

海洋公益性行业科研专项(201305043和201405010); 国家科技基础条件平台-水产种质资源平台项目资助 [Supported by the Public Science and Technology Research Funds Projects of Ocean (201305043 and 201405010); National Infrastructure of Fishery Germplasm Resources]

宋娜(1983—), 女, 山东乳山人; 博士; 主要从事渔业生态学研究。E-mail: songna624@163.com

高天翔(1962—), 男, 辽宁辽阳人; 博士; 主要从事渔业生态学研究。E-mail: gaotianxiang0611@163.com