不同BMI水平对新发房颤风险影响的Meta分析

2017-05-02陈金盛江灿郭军

陈金盛,江灿,郭军

· 循证理论与实践·论著 ·

不同BMI水平对新发房颤风险影响的Meta分析

陈金盛1,江灿1,郭军1

目的 系统评价不同体质指数(BMI)水平对普通人群新发心房颤动(房颤)风险的影响。方法 计算机检索Pubmed、CNKI数据库中关于BMI与普通人群新发房颤风险关系的观察性研究,检索时间截止至2016年7月。根据预先设定的文献纳入与排除标准,由2名评价员独立进行文献筛选、资料提取、质量评价等工作,将符合标准的文献纳入,利用RevMan 5.3软件进行Meta分析。结果 在初步检索得到的685篇文献中,共纳入12篇符合标准的文献。Meta分析结果显示,与正常组相比,超重组的房颤发病风险增加43%(RR=1.43,95%CI:1.30~1.57,P<0.00001),肥胖组的房颤发病风险增加89%(RR=1.89,95%CI:1.69~2.12,P<0.00001);与超重组相比,肥胖组的房颤发病风险增加32%(RR=1.32,95%CI:1.25~1.39,P<0.00001);与非肥胖组相比,肥胖组的房颤发病风险增加55%(RR=1.55,95%CI:1.41~1.69,P<0.00001)。结论 超重与肥胖明显增加普通人群新发房颤的风险,随着BMI水平的增加,新发房颤风险也在逐级增加。

心房颤动;体质指数;超重;肥胖;危险因素;Meta分析

心房颤动(AF)简称房颤,是临床上最常见的心律失常。资料显示,我国房颤的总体患病率为0.61%,呈现出随年龄增长而增加的趋势,其中80岁以上人群的患病率为7.5%,男性患病率高于女性[1]。房颤是心肌梗死、脑卒中和心力衰竭的主要危险因素[2-4]。房颤患者的死亡率是普通人的2倍,心力衰竭与脑卒中是主要的致死原因,在65岁以上的患者中,女性死亡率高于男性[5,6]。房颤及其引发的脑卒中、心力衰竭等并发症对人类的生命健康造成了很大的威胁,它正日益给社会带来沉重的医疗负担,因此,识别潜在的危险因素并加以有效控制,是实现房颤防控、减轻医疗负担的重要手段之一。相关研究表明,肥胖可增加普通人群新发房颤风险[7-20]。不同的BMI水平对普通人群新发房颤风险的影响分别如何,这个问题需要更多循证医学证据的解答。因此,本文采用Meta分析的方法对符合纳入标准的文献数据进行分析评估,以明确不同BMI水平对新发房颤风险的影响,从而为房颤防控策略的制定提供更可靠的循证医学证据。

1 资料与方法

1.1 纳入与排除标准

1.1.1 纳入标准 文献纳入标准:①前瞻性或回顾性队列研究;②研究对象为普通人群;③研究内容为BMI水平与新发房颤的关系;④观察终点为房颤发生。

1.1.2 排除标准 文献排除标准:①未使用WHO的BMI分类标准或其他明确定义的BMI分类标准;②未提供各个BMI水平中新发房颤病例数量;③研究对象为心脏手术后患者;④研究对象动物或细胞;⑤文献为综述、系统回顾或Meta分析。WHO的BMI分类标准如下:18.5 kg/m2≤BMI<25.0 kg/m2为正常;25.0 kg/m2≤BMI<30.0 kg/m2为超重;BMI≥30.0 kg/m2为肥胖。

1.2 文献检索 利用计算机检索Pubmed、CNKI数据库,文种限定为英文和中文,检索日期截止至2016年7月。英文检索词为:atrial fibrillation,obesity,overweight,body mass index。中文检索词为:房颤、心房颤动、肥胖、超重、体质指数。所有检索均采用主题词与自由词相结合方式。

1.3 数据提取 由两名评价员分别独立阅读所有检索得到的文献,然后根据纳入与排除标准进行文献筛选。结果如有分歧,则通过双方讨论或由第三位评价员进行确定。最后对纳入的文献进行数据提取。所要提取的文献内容如下:第一作者、出版年份、总样本量、各BMI水平级别的样本量、性别比例、随访时间、终点事件。

1.4 方法学质量评价 采用Downs and Black清单[21]对所纳入的队列研究的方法学质量进行评价。该评价量表包括5个部分共计27个条目,分别是报告质量(11分)、外部真实性(3分)、偏倚(7分)、混杂因素(6分)、效能(2分)。满分29分,得分越高,代表文献质量越高。

1.5 统计学处理 通过Revman 5.3软件对提取的数据进行Meta分析。采用χ2检验和I2检验对所纳入的研究进行异质性检验,如果I2≥50%,P≤0.05,则表明各研究结果之间存在异质性,采用随机效应模型进行分析;如果I2<50%,P>0.05,则表明各研究结果之间不存在异质性,采用固定效应模型进行分析。发表偏倚采用漏斗图进行评估。本研究的效应指标是相对危险度(RR)及其95%可信区间(CI),其中P值<0.05认为是差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果

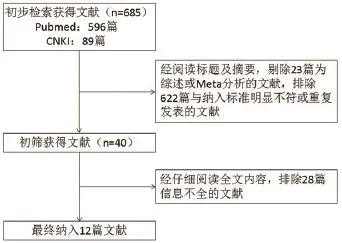

2.1 文献检索结果 初步检索共得到685篇文献,经阅读标题、摘要以后,剔除23篇为综述或Meta分析的文献,排除622篇明显不符合纳入标准或重复发表的文献,对初筛纳入的40篇文献进行全文内容的仔细阅读,其中28篇文献因无提供各个BMI水平中新发房颤病例的具体数据或无提供明确的BMI分类标准而被排除,最终纳入12篇原始文献,共计449 669人。文献筛选流程(图1)。

2.2 纳入文献的一般情况及质量评价 纳入文献的一般情况及质量评价(表1)。

图1 文献筛选流程图

表1 纳入研究的一般情况及质量评价

2.3 Meta分析结果

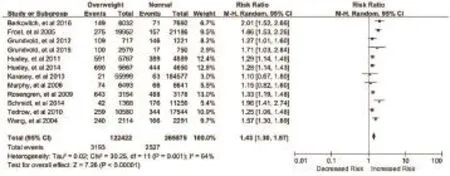

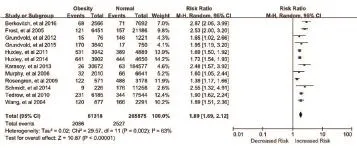

2.3.1 超重组与正常组新发房颤风险的比较 对超重组与正常组的新发房颤风险进行比较,异质性检验结果为P=0.001,I2=64%,采用随机效应模型进行Meta分析。结果显示,超重组房颤发病率为2.61%,正常组房颤发病率为0.95%。与正常组相比,超重组的房颤发病风险增加43%,两组差异具有统计学意义(RR=1.43,95%CI:1.30~1.57,P<0.00001)(图2)。

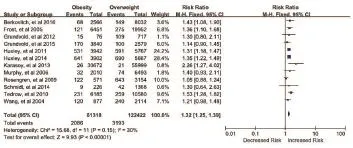

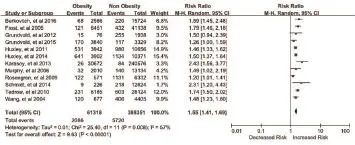

2.3.2 肥胖组与超重组新发房颤风险的比较 对肥胖组与超重组的新发房颤风险进行比较,异质性检验结果为P=0.15,I2=30%,采用固定效应模型进行Meta分析。结果显示,肥胖组房颤发病率为3.40%,超重组房颤发病率为2.61%。与超重组相比,肥胖组的房颤发病风险增加32%,两组差异具有统计学意义(RR=1.32,95%CI:1.25~1.39,P<0.00001)(图3)。

2.3.4 肥胖组与正常组新发房颤风险的比较 对肥胖组与正常组的新发房颤风险进行比较,异质性检验结果为P=0.002,I2=63%,采用随机效应模型进行Meta分析。结果显示,肥胖组房颤发病率为3.40%,正常组房颤发病率为0.95%。与正常组相比,肥胖组的房颤发病风险增加89%,两组差异具有统计学意义(RR=1.89,95%CI:1.69~2.12,P<0.00001)(图4)。

2.3.5 肥胖组与非肥胖组新发房颤风险的比较 对肥胖组与非肥胖组(超重组+正常组)的新发房颤风险进行比较,异质性检验结果为P=0.008,I2=57%,采用随机效应模型进行Meta分析。结果显示,肥胖组房颤发病率为3.40%,非肥胖组房颤发病率为1.47%。与非肥胖组相比,肥胖组的房颤发病风险增加55%,两组差异具有统计学意义(RR=1.55,95%CI:1.41~1.69,P<0.00001)(图5)。

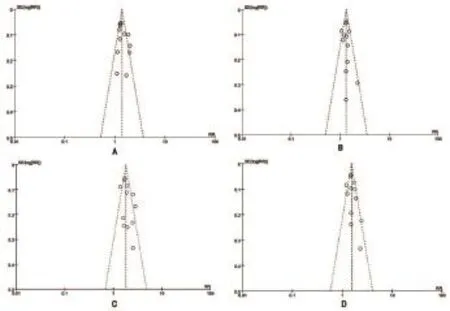

2.3.6 发表偏倚 对以上各组进行漏斗图分析,结果都呈基本对称的倒置漏斗图(图6),表明各研究结果之间无显著发表偏倚。

图2 超重组与正常组新发房颤风险的比较

图3 肥胖组与超重组新发房颤风险的比较

图4 肥胖组与正常组新发房颤风险的比较

图5 肥胖组与非肥胖组新发房颤风险的比较

图6 不同BMI水平对新发房颤风险影响比较的漏斗图(A:超重组与正常组新发房颤风险比较的漏斗图;B:肥胖组与超重组新发房颤风险比较的漏斗图;C:肥胖组与正常组新发房颤风险比较的漏斗图;D:肥胖组与非肥胖组新发房颤风险比较的漏斗图)

3 讨论

房颤是一种最严重的心房电活动紊乱,它往往伴随着较高的心血管疾病发病率与死亡率。诱发房颤的危险因素不是单一的,其发病机制也较为复杂。本文通过Meta分析表明,在普通人群中,超重与肥胖可增加新发房颤的风险,随着BMI水平的增加,新发房颤风险也在逐级增加。

超重与肥胖增加普通人群新发房颤风险的机制尚未完全明确。与肥胖相关的阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停低通气综合征(OSAHS)可能是肥胖诱发房颤的一个重要介导因素[22]。OSAHS可以导致夜间血氧饱和度下降,由此引发的间歇性低氧和高碳酸血症可以增加交感神经张力,引起心房有效不应期缩短与心肌细胞钙超载,这可能跟增加房颤发病风险相关[23,24]。肥胖可能影响心脏收缩功能,引起左房增大,促进房颤基质的形成[25]。肥胖患者左房增大的一个可能机制是整体血压水平的增高[26]。肥胖与高血压可协同增加房颤的发生风险,可能的机制是体重增加与左心室肥厚有关,并增加高血压的发病风险,而长期高血压可引起左心室重构,最终导致左心室、左心房增大,进一步增加房颤发病风险[27]。研究指出,血浆高敏C反应蛋白(hs-CRP)与房颤相关[28],肥胖患者体内hs-CRP水平明显高于正常体重者[29],而hs-CRP是一种公认的炎症标志物,Bruins等[30]的研究认为房颤与炎症相关,据此可推断,肥胖有可能是通过一种慢性炎症状态来诱发房颤。此外,肥胖患者往往伴随着代谢综合征,包括糖尿病、高血压病、高脂血症等,这些因素都会增加房颤的发病风险。其他的解释包括左心室舒张功能减低、血容量增加、肾素-血管紧张素-醛固酮系统等神经体液机制的激活以及脂肪浸润引起的心肌组织结构和电生理特性的异常等[19,31]。

综上所述,超重与肥胖可能通过多种机制增加普通人群的新发房颤风险,BMI水平与新发房颤风险密切相关。较高的BMI水平往往预示着较高的新发房颤风险。BMI也许可以作为房颤发病的一个预测因素,在房颤防控策略的制定中应得到充分的认识。然而,由于本文所纳入研究的数据尚不全面,各研究的质量参差不齐,各研究结果之间也存在统计学异质性,同时也不能完全调整其他风险因素、药物使用等的影响。考虑到以上的局限性,还有待进一步开展更多、更详细、更精确的研究来得到更加稳定可信的结论。

[1] 周自强,胡大一,陈捷,等. 中国心房颤动现状流行病学研究[J]. 中华内科杂志,2004,41(2):491-4.

[2] Wang TJ,Larson MG,Levy D,et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study[J]. Circulation,2003,107(23): 2920-5.

[3] Shames J,Weitzman S,Nechemya Y,et al. Association of atrial fibrillation and stroke: analysis of Maccabi Health Services Cardiovascular Database[J]. Isr Med Assoc J,2015,17(8):486-91.

[4] Soliman EZ,Lopez F,O'Neal WT,et al. Atrial Fibrillation and Risk of ST-Segment-Elevation Versus Non-ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study[J]. Circulation,2015,131(21):1843-50.

[5] Camm AJ,Lip GY,De Caterina R,et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association[J]. Europace,2012,14(10):1385-413.

[6] Fuster V,Ryden LE,Cannom DS,et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines[J]. Circulation,2011,123(10):e269-367.

[7] Berkovitch A,Kivity S,Klempfner R,et al. Body mass index and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in middle-aged adults[J]. Am Heart J,2016,173:41-8.

[8] Frost L,Hune LJ,Vestergaard P. Overweight and obesity as risk factors for atrial fibrillation or flutter: the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study[J]. Am J Med,2005,118(5):489-95.

[9] Grundvold I,Skretteberg PT,Liestol K,et al. Importance of physical fitness on predictive effect of body mass index and weight gain on incident atrial fibrillation in healthy middle-age men[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2012,110(3):425-32.

[10] Grundvold I,Bodegard J,Nilsson PM,et al. Body weight and risk of atrial fibrillation in 7,169 patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes; an observational study[J]. Cardiovasc Diabetol,2015,14:5.

[11] Huxley RR,Lopez FL,Folsom AR,et al. Absolute and attributable risks of atrial fibrillation in relation to optimal and borderline risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study[J]. Circulation,2011,123(14):1501-8.

[12] Huxley RR,Misialek JR,Agarwal SK,et al. Physical activity, obesity, weight change, and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study[J]. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol,2014,7(4): 620-5.

[13] Karasoy D,Bo Jensen T,Hansen ML,et al. Obesity is a risk factor for atrial fibrillation among fertile young women: a nationwide cohort study[J]. Europace,2013,15(6):781-6.

[14] Murphy NF,Maclntyre K,Stewart S,et al. Long-term cardiovascular consequences of obesity: 20-year follow-up of more than 15 000 middle-aged men and women (the Renfrew-Paisley study)[J]. Eur Heart J,2006,27(1):96-106.

[15] Rosengren A,Hauptman PJ,Lappas G,et al. Big men and atrial fibrillation: effects of body size and weight gain on risk of atrial fibrillation in men[J]. Eur Heart J,2009,30(9):1113-1120.

[16] Schmidt M,Botker HE,Pedersen L,et al. Comparison of the frequency of atrial fibrillation in young obese versus young nonobese men undergoing examination for fitness for military service[J]. Am J Cardi ol,2014,113(5):822-6.

[17] Tedrow UB,Conen D,Ridker PM,et al. The long- and shortterm impact of elevated body mass index on the risk of new atrial fibrillation the WHS (women's health study)[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol,20 10,55(21):2319-27.

[18] Vermond RA,Geelhoed B,Verweij N,et al. Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation and Relationship With Cardiovascular Events, Heart Failure, and Mortality: A Community-Based Study From the Netherlands[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol,2015,66(9):1000-7.

[19] Wang TJ,Parise H,Levy D,et al. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation[J]. JAMA,2004,292(20):2471-7.

[20] Wilhelmsen L,Rosengren A,Lappas G. Hospitalizations for atrial fibrillation in the general male population: morbidity and risk factors[J]. J Intern Med,2001,250(5):382-9.

[21] Downs SH,Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and non-randomized studies of health care interventions[J]. J Epidemiol Community,1998,52(6):377-84.

[22] Gami AS,Friedman PA,Chung MK,et al. Therapy Insight: interactions between atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea[J]. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med,2005,2(3):145-9.

[23] Gami AS,Hodge DO,Herges RM,et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation[J]. J Am Coll Cardio l,2007,49(5):565-71.

[24] Sahadevan J,Srinivasan D. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with cardiac arrhythmias[J]. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med,2012,14(5):520-8.

[25] Allessie MA,Boyden PA,Camm AJ,et al. Pathophysiology and prevention of atrial fibrillation[J]. Circulation,2001,103(5):769-77.

[26] ALEXANDER JK,DENNIS EW,SMITH WG,et al. Blood volume, cardiac output, and distribution of systemic blood flow in extreme obesity[J]. Cardiovasc Res Cent Bull,1962,1:39-44.

[27] 施继红,季春鹏,邢爱君,等. 收缩压联合体重指数对新发心房颤动的影响[J]. 中华心血管病杂志,2016,44(3):231-7.

[28] Zheng LH,Sun W,Yao Y,et al. Associations of big endothelin-1 and C-reactive protein in atrial fibrillation[J]. J Geriatr Cardiol,2016,13 (5):465-70.

[29] Aronson D,Bartha P,Zinder O,et al. Obesity is the major determinant of elevated C-reactive protein in subjects with the metabolic syndrome[J]. Int J Obesity,2004,28(5):674-9.

[30] Bruins P,te Velthuis H,Yazdanbakhsh AP,et al. Activation of the complement system during and after cardiopulmonary bypass surgery: postsurgery activation involves C-reactive protein and is associated with postoperative arrhythmia[J]. Circulation,1997,96(10):3542-9.

[31] Zacharias A,Schwann TA,Riordan CJ,et al. Obesity and risk of newonset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery[J]. Circulation,2005,112 (21):3247-55.

本文编辑:翁鸿,姚雪莉

The effect of BMI category on the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation: a Meta-analysis

CHEN Jin-sheng*,JIANG Can,GUO Jun.*Department of Cardiology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Guangzhou, 510630, China.

GUO Jun, E-mail: dr.guojun@163.com

Objective To evaluate the effect of different BMI levels on the risk of new atrial fibrillation in the general population. Methods Observational studies of the relationship between BMI and the risk of new atrial fibrillation in the general population published in Pubmed and CNKI database before July 2016 were retrieved. Two reviewers independently completed the literature screening, data extraction and quality evaluation, and used RevMan 5.3 software for meta-analysis. Results There were 12 articles selected from 685 retrieved articles. Compared with the normal group, the risk of atrial fibrillation increased by 43% (RR=1.43, 95%CI: 1.30~1.57, P<0.00001) in the overweight group, and the risk of AF increased by 89% (RR=1.89, 95%CI: 1.69~2.12, P<0.00001) in the obese group. Compared with the overweight group, the risk of atrial fibrillation in the obese group increased by 32% (RR=1.32, 95%CI: 1.25-1.33, P<0.00001). Compared with the non-obese group, the risk of atrial fibrillation in the obese group increased by 55% (RR=1.55, 95%CI: 1.41~1.69, P<0.00001). Conclusion Overweight and obesity significantly increase the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in general population, and there is a graded relationship between increased BMI and increased risk of new-onset AF.

Atrial fibrillation; Body mass index; Overweight; Obesity; Risk factors; Meta-analysis

R541.75

A

1674-4055(2017)03-0265-04

国家自然科学基金资助项目(81673635)

1510630 广州,暨南大学附属第一医院心内科

郭军,E-mail:dr.guojun@163.com

10.3969/j.issn.1674-4055.2017.03.03