The current role of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

2017-04-17WanYeeLauandStephanieHiuYanLau

Wan Yee Lau and Stephanie Hiu Yan Lau

Hong Kong, China

The current role of radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

Wan Yee Lau and Stephanie Hiu Yan Lau

Hong Kong, China

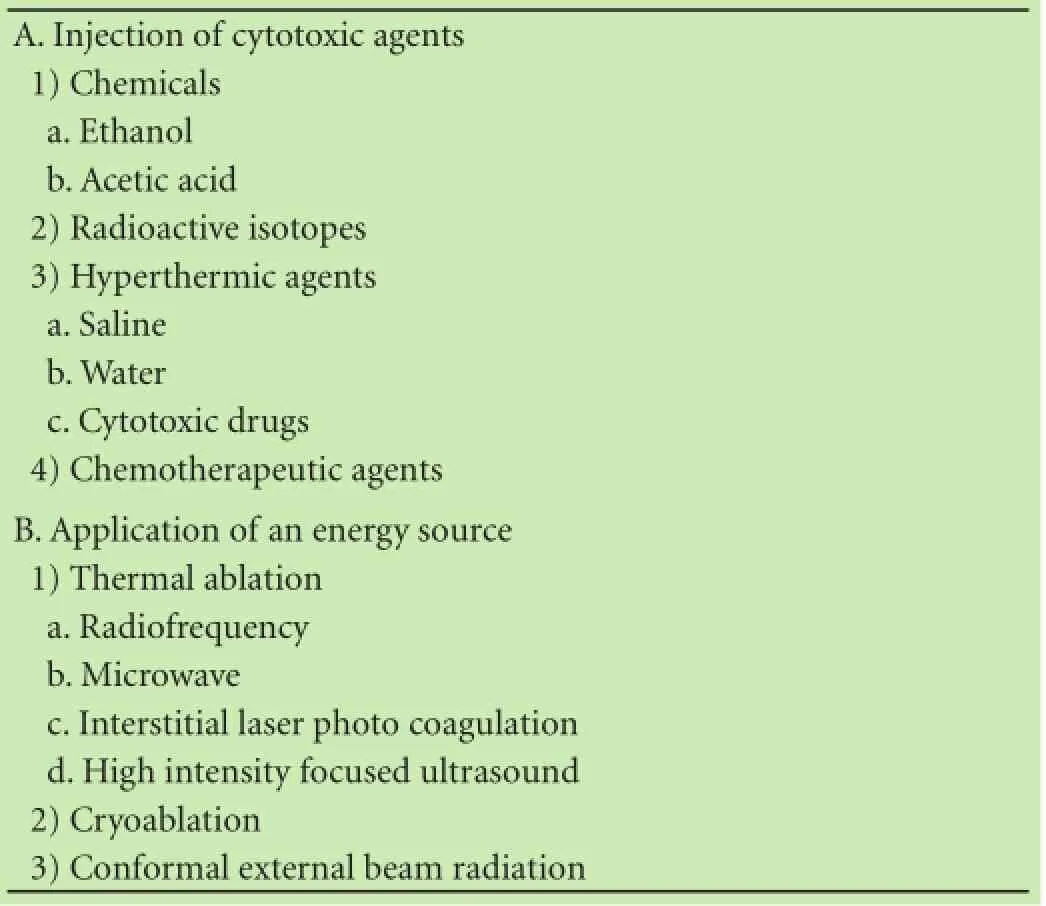

Local ablative therapy is used in treating liver tumors by either injection of cytotoxic agents (chemicals, radioactive isotopes, hyperthermic agents or chemotherapeutic agents) or application of an energy source to achieve thermal ablation, cryoablation or conformal external beam radiation (Table 1).

Table 1. Local ablative therapy

There are many advantages of local ablative therapy. The treatment is minimally invasive with little damage to surrounding liver parenchyma, little side effects, safe and can be carried out under local anesthesia or intravenous sedation.

Two systematic reviews showed that radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is better than other forms of local ablative therapy in treating patients with liver tumors on overall survival (OS), local tumor recurrence rate, complete tumor necrosis rate and number of treatments required to achieve complete tumor ablation.[1,2]With the possible exception of microwave ablation, RFA is the best form of local ablative therapy.[3-5]

Local ablative therapy using RFA mainly involves percutaneous RFA under ultrasound or computed tomographic guidance. For difficult tumor locations, either the laparoscopic or even the open surgical approaches can be used. However, when RFA is done in open surgery, RFA loses the advantages of minimal invasiveness, although the procedure is still less invasive than open liver resection.

RFA uses a closed loop circuit which creates an alternation of electric field agitating ions within target tissues, reaching a temperature of 50 ℃ to 100 ℃ and resulting in consequent necrosis.[6]Large non-randomized studies on Child-Pugh A patients undergoing RFA for early stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) reported that 5-year OS rates were from 50% to 64%, with extremely low post-procedural mortality and morbidity rates.[7-9]

The excellent results obtained from RFA in treating HCC have led some clinicians to use RFA as the first-line treatment instead of surgery. Furthermore, RFA applications resulted in the change in the recommendation of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) Staging System in treating BCLC stage 0 HCCs.

In the older form of BCLC, for patients with stage 0 HCC [patients with Child-Pugh A, Performance Status Test (PST) 0, a single HCC <2 cm/carcinoma in situ, with no portal hypertension], the recommended first-line treatment is surgical resection.[10]In the recent BCLC,the recommendation has changed to RFA as the first-line treatment.[11]

The usual indications for RFA to treat HCC are Child-Pugh A or B, a small HCC (how small is small will be discussed later in this article), usually tumor number≤3 or otherwise require repeated treatment sessions, and not a candidate for liver transplantation (with portal hypertension or decompensated liver function). RFA is especially suitable for patients who are not candidates for surgical treatment because of poor general condition, poor liver function or recurrence after liver resection.[12]

What are the evidences in supporting RFA to treat single HCC <2 cm? In other words, why the change in the BCLC recommendation, and at least for some centers to use RFA as the first-line treatment for patients with early stage HCC with cirrhosis?

A multicenter prospective study on patients with single ≤2 cm HCC reported a 97% sustained complete response after RFA.[13]The main competitor in curative treatment for HCC with a solitary small HCC <5 cm, with good liver function (Child-Pugh A or B) and with good general condition is partial hepatectomy. Liver transplantation cannot be used as a first-line treatment for these patients, especially in regions where the prevalence of HCC is high and the rate of deceased liver donation is low, like in many countries in the East.

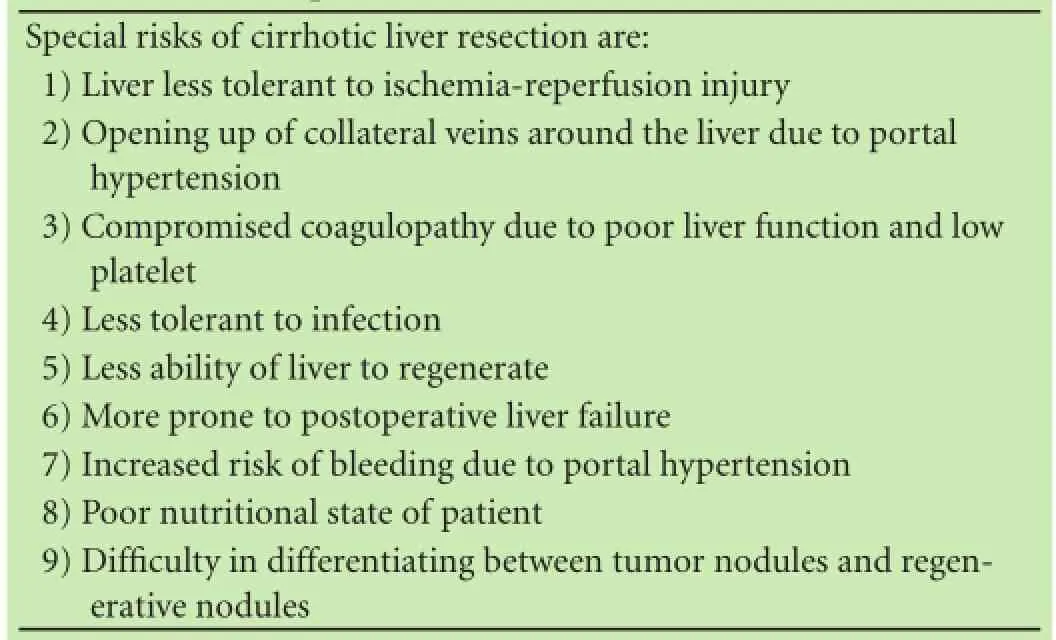

Recent advances in liver surgery have significantly decreased the perioperative mortality rate, approaching 0% for non-cirrhotic liver resection and <5% for cirrhotic liver resection.[14]Unfortunately, only 10%-30% of patients have resectable HCC at the time of diagnosis because of poor general condition, poor liver function or unresectable/metastatic HCC.[15]In the East, over 70% of HCC are associated with cirrhotic livers. The special risks of cirrhotic liver resection are listed in Table 2. Furthermore, partial hepatectomy, like RFA, is a local treatment but it has higher treatment risks, lower feasibility rate and more postoperative pain.

Table 2. Special risks of cirrhotic liver resection

To compare RFA versus partial hepatectomy as a first-line treatment of HCC, there are three important points to consider:

(1) Outcome measurements

The most important primary outcome measurement is OS. Other less important secondary outcome measurements include recurrence-free survival, post-treatment morbidity/mortality, collateral damage to adjacent tissues, feasibility (e.g. for multiple tumors, in patients with compromised liver function), chance for re-treatment for recurrent HCC, and the number of re-treatment that can be carried out for tumor re-recurrence.

The comparison between RFA and partial hepatectomy on these primary and secondary outcome measurements will be discussed in more details later in this article.

(2) Level of evidence in the evidence-based hierarchy[16]

Only level 1 evidence in evidence based medicine is used to compare the primary outcome measurement of OS, i.e. only randomized comparative studies and metaanalyses are used.

(3) The comparison is limited to patients who are suitable to be treated by both RFA and partial hepatectomy, otherwise the comparison is meaningless. Thus, the comparison is made only for small HCC <5 cm as HCC >5 cm is not suitable for RFA; and the approach used for RFA can be percutaneous (in the majority of patients), laparoscopic or open surgery.

Three randomized comparative studies[17-19]and a study using the Markov model to simulate a randomized comparative study[20]showed the OS to be similar between RFA and liver resection. Unfortunately, all these studies have been criticized to have major methodological bias.[21]On the other hand, a fourth randomized trial demonstrated superiority of liver resection over RFA in achieving OS.[22]

How should we look at all these controversies in OS in level 1 evidence-based medicine?

The main criticism of all the above mentioned level 1 studies is the failure to exclude patients with HCC which are less effective to RFA treatment. These include patients with HCC at difficult sites for RFA (e.g. in the subdiaphragmatic region), HCC near to “heat sinks” and including various sizes of HCC lesions. A large metaanalysis has clearly demonstrated that the effectiveness of RFA rapidly decreases for HCC >3 cm and in lesions near to a large vessel which can produce “heat sink effect”.[8]

For “heat sink”, the best solution is proper patient selection.

For lesions in difficult locations, RFA using the laparoscopic or open approach can solve the problem.

The main limitation of effectiveness of RFA on OS in treating HCC is size of the lesion. Lu et al[23]conducted a study on the biological behavior of HCC and found that as HCC reached to 3 cm, its biological behavior is more aggressive with increasing incidences of capsular invasion, worsening of histological grades, and exhibiting satellite and tumor nodules. All these aggressive biological behaviors were associated with worse long-term OS after liver resection. The technical solutions to effectively treating large HCC lesions include the use of complex electrode geometry (e.g. Multiple Electrodes, Cool-tip™Ablation System E Series, Covidien, Boulder, CO, USA, or LeVeen Electrode, Radiotherapeutics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), or multiple punctures or different treatment sessions.

For HCC 3-5 cm in size, randomized comparative studies have shown that RFA+ethanol injection produced better OS and disease-free survival than RFA alone.[24]Also, RFA+transarterial chemoembolization (TACE)[25]and a meta-analysis[26]has better OS than RFA alone.

Thus, evidence-based medicine suggests that the OS of RFA is equivalent to liver resection for patients with HCC ≤2 cm. For HCC between 2-3 cm, the effect of RFA is possibly equivalent to liver resection. For HCC between 3-5 cm, RFA should be used together with ethanol injection or TACE to achieve OS the same as in liver resection. For HCC >5 cm, liver resection should be the first-line treatment.

Unless treating HCC ≤2 cm, or possibly ≤3 cm, studies showed that the recurrence free survival is worse with RFA than liver resection.[21,22]However, as these patients can be treated with further sessions of RFA, the OS is not affected as discussed previously if these patients are carefully selected and additional sessions of RFA are given.

A study showed that whether RFA resulted in complete necrosis is an important factor of long-term overall and disease-free survivals.[27]There are ways to ensure complete tumor necrosis in RFA. During treatment and with the use of SonoVue (Bracco, Mineapolis, MN, USA), a contrast agent used for contrast enhanced ultrasound of the liver, RFA should be given until there is no contrast enhancement in the tumor tissues. Within 4 weeks after RFA treatment, an intravenous contrast CT scan should be carried out and any residual HCC with contrast enhancement should be re-treated with RFA.[12,17]The concept of adequate RFA treatment is shown in Fig. This concept is like carrying out histopathological examination of surgically resected specimens to look at the resection margin for R0 liver resection.[12,17]

The morbidity and mortality rates after RFA range from 2% to 4% and 0.2% to 0.5%, respectively.[28-31]While the corresponding morbidity and mortality rates after liver resection range from 30% to 50% (15× as high as RFA), and 2% for non-cirrhotic liver resection and 5% for cirrhotic liver resection, respectively.

When compared to liver resection, RFA uses a more minimal invasive approach, there is no need to mobilize the liver, it causes little damage to the liver parenchyma; there is no need for liver blood inflow occlusion which may cause ischemia-reperfusion injury to the liver; there is much less pain after the treatment and the patient recovery is much faster.

RFA has much less limitations compared with liver resection, especially for patients with multiple tumors or with compromised liver function.

The chance of re-treatment is higher with RFA than that with liver re-resection.

For RFA, re-treatment for recurrent HCC can be carried out many times and it is not unusual to have 7 or more re-treatments. For liver re-resection, at the most it can be done 2 to 3 times.

Table 3 summarizes the comparison between RFA and liver resection.

Thus evidence-based medicine shows in selected patients with small HCC, RFA can replace liver resection to be the first-line of curative treatment.

Fig. The concept of adequate RFA treatment. The concept is like histological examination of surgical resection margin to look for R0 liver resection.

Table 3. Comparison of RFA with liver resection

Microwave ablation is an emerging technology which has the potential to achieve larger and more regular ne-crotic areas in comparison with RFA. It has the following theoretical advantages over RFA: (a) faster delivery; (b) a wider zone of active heating; (c) higher intra-tumoral temperature; (d) less susceptability to ‘heat sink’ when performed near to large vessels.[32]

In conclusion, RFA is an effective and safe treatment for HCC. In selected patients, it produces similar OS compared to patients treated with liver resection, but with better secondary outcome measurements. The results of RFA in treating HCC 3 to 5 cm can be improved by adding TACE or ethanol injection. Microwave ablation is a new and promising treatment for patients with small HCC.

Contributors: LWY proposed the study. Both authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. LWY is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Galandi D, Antes G. Radiofrequency thermal ablation versus other interventions for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004:CD003046.

2 Sutherland LM, Williams JA, Padbury RT, Gotley DC, Stokes B, Maddern GJ. Radiofrequency ablation of liver tumors: a systematic review. Arch Surg 2006;141:181-190.

3 Facciorusso A, Di Maso M, Muscatiello N. Microwave ablation versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyperthermia 2016;32:339-344.

4 Chinnaratha MA, Chuang MY, Fraser RJ, Woodman RJ, Wigg AJ. Percutaneous thermal ablation for primary hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:294-301.

5 Lucchina N, Tsetis D, Ierardi AM, Giorlando F, Macchi E, Kehagias E, et al. Current role of microwave ablation in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas. Ann Gastroenterol 2016;29:460-465.

6 Facciorusso A, Serviddio G, Muscatiello N. Local ablative treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: An updated review. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016;7:477-489.

7 Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Koike Y, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases. Cancer 2005;103:1201-1209.

8 Mulier S, Ni Y, Jamart J, Ruers T, Marchal G, Michel L. Local recurrence after hepatic radiofrequency coagulation: multivariate meta-analysis and review of contributing factors. Ann Surg 2005;242:158-171.

9 Yang W, Yan K, Goldberg SN, Ahmed M, Lee JC, Wu W, et al. Ten-year survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation as a first-line treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:2993-3005.

10 Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-1022.

11 Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16018.

12 Livraghi T. Local ablative therapy. In: Lau WY, ed. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Singapore World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. 2008; Ch 29:645-659.

13 Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, Rolle E, Solbiati L, Tinelli C, et al. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology 2008;47:82-89.

14 Belghiti J. Surgical treatment. In: Lau WY, ed. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Singapore World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. 2008; Ch 16:387-408.

15 Lau WY, Lai EC. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and recent advances. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2008;7:237-257.

16 Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med 2016;21:125-127.

17 Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2006;243:321-328.

18 Lü MD, Kuang M, Liang LJ, Xie XY, Peng BG, Liu GJ, et al. Surgical resection versus percutaneous thermal ablation for earlystage hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized clinical trial. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2006;86:801-805.

19 Feng K, Yan J, Li X, Xia F, Ma K, Wang S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency ablation and surgical resection in the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;57:794-802.

20 Cho YK, Kim JK, Kim WT, Chung JW. Hepatic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for very early stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a Markov model analysis. Hepatology 2010;51:1284-1290.

21 Wang Y, Luo Q, Li Y, Deng S, Wei S, Li X. Radiofrequency ablation versus hepatic resection for small hepatocellular carcinomas: a meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2014;9:e84484.

22 Cucchetti A, Piscaglia F, Cescon M, Ercolani G, Pinna AD. Systematic review of surgical resection vs radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:4106-4118.

23 Lu XY, Xi T, Lau WY, Dong H, Xian ZH, Yu H, et al. Pathobiological features of small hepatocellular carcinoma: correlation between tumor size and biological behavior. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2011;137:567-575.

24 Zhang YJ, Liang HH, Chen MS, Guo RP, Li JQ, Zheng Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radiofrequency ablation with or without ethanol injection: a prospective randomized trial. Radiology 2007;244:599-607.

25 Cheng BQ, Jia CQ, Liu CT, Fan W, Wang QL, Zhang ZL, et al. Chemoembolization combined with radiofrequency ablation for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 3 cm: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:1669-1677.

26 Wang X, Hu Y, Ren M, Lu X, Lu G, He S. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation combined with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinomas comparedwith radiofrequency ablation alone: a time-to-event metaanalysis. Korean J Radiol 2016;17:93-102.

27 Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Sandri M, Pachera S, Pedrazzani C, Tasselli S, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: prognostic factors for survival. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:143-149.

28 Horiike N, Iuchi H, Ninomiya T, Kawai K, Kumagi T, Michitaka K, et al. Influencing factors for recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radiofrequency ablation. Oncol Rep 2002;9:1059-1062.

29 Livraghi T, Solbiati L, Meloni MF, Gazelle GS, Halpern EF, Goldberg SN. Treatment of focal liver tumors with percutaneous radio-frequency ablation: complications encountered in a multicenter study. Radiology 2003;226:441-451.

30 Rhim H. Complications of radiofrequency ablation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Imaging 2005;30:409-418.

31 Akahane M, Koga H, Kato N, Yamada H, Uozumi K, Tateishi R, et al. Complications of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: imaging spectrum and management. Radiographics 2005;25:S57-68.

32 Yu J, Yu XL, Han ZY, Cheng ZG, Liu FY, Zhai HY, et al. Percutaneous cooled-probe microwave versus radiofrequency ablation in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Gut 2016 Nov 24. pii: gutjnl-2016-312629.

Received January 4, 2017

Accepted after revision January 25, 2017

Live life to the fullest, and focus on the positive.

—Matt Cameron

Author Affiliations: Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China (Lau WY and Lau SHY)

Professor Wan Yee Lau, MD, FRCS, FACS, FRACS(Hon), Professor of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China (Tel: +852-2632-2626; Fax: +852-2632-5459; Email: josephlau@cuhk.edu.hk)

© 2017, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60182-0

Published online February 24, 2017.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Pancreaticoduodenectomy for borderline resectable pancreatic head cancer with a modified artery-first approach technique

- Long-term outcome of patients with chronic pancreatitis treated with micronutrient antioxidant therapy

- High-grade pancreatic intraepithelial lesions: prevalence and implications in pancreatic neoplasia

- HIDA scan for functional gallbladder disorder: ensure that you know how the scan was done

- Novel HBV mutations and their value in predicting efficacy of conventional interferon

- Serum soluble ST2 is a promising prognostic biomarker in HBV-related acute-on-chronic liver failure