Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung presenting as deep vein thrombosis: an evidence of anchoring bias

2017-04-09WalidIbrahimHossamAbubakarLubnaOsmanMuhammadSheikh

Walid Ibrahim, Hossam Abubakar Lubna Osman, Muhammad Sheikh

1 Department of Internal Medicine, Wayne State University; Detroit Medical Center, Detroit, MI, USA

2 Volunteer at Department of Internal Medicine, Wayne State University; Detroit Medical Center, Detroit, MI, USA

Key Messages:

- Skeletal metastasis is a common manifestation of non-small cell lung cancer, however, distal appendicular metastasis is uncommon.- History of active or remote malignancy must be considered when entertaining a diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis especially when the disease course is atypical.

- Anchoring is a common cognitive bias that results in diagnostic errors.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies worldwide with close to 1.8 million new cases annually. It is the leading cause of cancer mortality amongst males and second to only breast cancer amongst females.1Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a common lung cancer that is often diagnosed at the advanced stages of the disease and accounts for 80-85% of lung cancers and the majority of NSCLC patients have advanced-stage (IIIB/IV) disease at diagnosis.2Skeletal metastasis is a common manifestation in patients with lung cancer and accounts for 16% of all metastatic diseases.3However, distal appendicular skeletal metastasis, especially distal to the knee and elbow joints, is relatively rare. Identifying such uncommon presentations may be delayed or missed due to cognitive errors including anchoring bias. Knowledge and insight of such errors may possibly reduce their incidence and their consequent preventable patient injury.

The purpose of this case report was to raise the awareness of health care providers about early recognition of cognitive diagnostic error and anchoring bias.

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old female with a 3-day history of severe left lower extremity pain and swelling was included in this study. Her pain initially started 2 months ago but had acutely worsened 3 days prior to presentation. The pain was generalized extending from the lower one-third of her thigh to her ankle, severe in intensity, dull in nature, exacerbated by movement of her extremity with no reported alleviating factor. Associated symptoms included swelling and tightness around her calf muscle. She was unable to ambulate due to the severe pain. The patient reported no history of numbness, tingling, loss of sensation, erythema of her limb or fevers.

She suffered from remote localized laryngeal cancer nine years prior to her presentation and had received radiation therapy and she also developed chronic lymphocytic leukemia and was undergoing regular observation until presentation. She had a 24-year history of smoking. At presentation, her heart rate was 110 beats per minute and remaining vital signs were normal. Her physical examination revealed a grossly swollen left lower extremity from the calf to the dorsum of the foot, with no erythema, tenderness or warmth of the affected skin. Assessment of strength in the right lower extremity was 5/5 and strength was limited by severe pain in the left lower extremity. Pulses and sensation were intact bilaterally.

Complete blood count was normal except markedly increased level of leukocytosis (white cell count 92,100/mL)with lymphocytic predominance consistent with patient’s history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Serum chemistry panels and creatine phosphokinase level were normal. Left lower extremity Duplex U/S revealed a complex echogenic area in the left popliteal vein with partial flow and compressibility concerning for acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT)(Figure 1a, b).

The patient was diagnosed with malignancy-associated DVT. She was subcutaneously administered a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin 80 mg,twice daily. Over the next few days, her pain continued to worsen and was minimally relived after receiving intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. On day 5 of admission, imaging examination was deemed necessary to rule out alternative soft tissue or vascular pathology.CT angiography of the left lower extremity revealed an enhanced mass measuring 3 × 2 cm2adjacent to and wrapping around the popliteal artery and vein, and another contrast-enhanced mass (5.5 × 3.5 cm2) replacing the fibular head in addition to a popliteal vein thrombus previously shown on the left lower extremity duplex US(Figure 2). Given the patient’s oncological history, radiological findings were concerning for metastatic disease.Ultrasound-guided core biopsy of the fibular head mass revealed poorly differentiated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung (Figure 3). A contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed 3 lung nodules, 2 in the left upper lobe and 1 in the right upper lobe (the largest of which measuring 1.3 × 4.6 cm2) with extensive bilateral mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy consistent with stage 4 adenocarcinoma of the lung employing TNM Classification for Lung Cancer (Figure 4).3Further metastatic workup including CT abdomen and pelvis showed extensive lymphadenopathy.

The patient was discharged from the hospital in stable

Figure 1: Duplex ultrasound scan of the left lower extremity.

Note: (a) Duplex ultrasound showing left popliteal vein with only partial flow and partial compressibility for a thrombus. (b)Duplex ultrasound showing left calf edema.

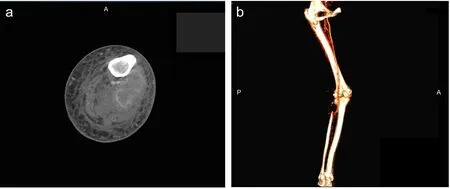

Figure 2: CT angiography of the left lower extremity.

Note: (a) CT angiography of the left lower extremity showing a 3 × 2 cm2enhancement adjacent to and wrapping around the popliteal artery and vein, and another contrast-enhanced mass replacing the fibular head. (b) CT angiography, showing a peripherally enhancing 3 × 2 cm2structure in the popliteal fossa intimately abutting the artery and vein. A: Anterior; P: posterior.

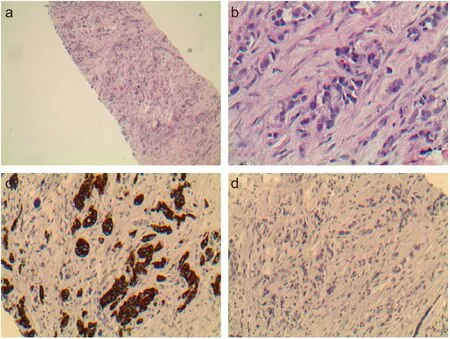

Figure 3: Ultrasound-guided core biopsy of the fibular head mass showing poorly differentiated carcinoma.

Figure 4: CT scans of the chest.

Note: (a) Low power view showing poorly differentiated carcinoma. (b) High power view showing poorly differentiated carcinoma with rare glandular formation.(c) Immunohistochemical stains showed the tumor cells are positive for cytokeratin 7. (d)Fibular head mass immunostained negative for cytokeratin 20. The above findings are consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of lung primary. Original magnification: a, ×100; b-d, × 400.

数据分析用SPSS18.0系统;计量(±s),t检验;计数(n,%),X2检验;P<0.05指有差异,符合统计学意义。

Note: (a) A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest revealed left upper lobe measuring 1.3 × 4.6 cm2. (b) A CT scan of the chest with contrast showing extensive mediastinal lymphadenopathy. A: Anterior.condition after completing 3 sessions of palliative localized radiation therapy with significant pain relief. She then completed 7 further sessions in the outpatient setting after which she was lost to follow up.

DISCUSSION

Skeletal metastasis, a common manifestation in patients with lung cancer, is attributed to the bone microenvironment, which harbors receptors for tumor-secreted proteins making it a preferred site of metastasis.4The axial skeleton is more commonly involved than the appendicular skeleton and metastatic lesions distal to the elbow and knee as seen in our patient, which is a relatively rare phenomenon.5-8Skeletal metastasis is associated with significant complications collectively known as skeletal-related events including intractable pain, pathological fractures, hypercalcemia and the need for radiation or surgical intervention for symptom relief.9We presented a case of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung presenting as DVT and intractable pain due to a metastatic bone lesion causing venous compression and blood stasis. Rajan et al.10reported a similar case of a 60-year-old man with a past medical history of right sided renal cell carcinoma successfully treated with nephrectomy who presented 5 years later with left lower leg edema and swelling which was initially diagnosed as DVT. Further workup revealed a huge soft tissue mass at the left fibular shaft adjacent to the deep calf veins. A bone biopsy from the fibula confirmed the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma.Both cases demonstrate the importance of considering the history of active and remote malignancy when evaluating a patient with a working diagnosis of DVT.

Our case is a common cognitive bias that resulted in a diagnostic error. A diagnostic error is defined as any mistake or failure in the diagnostic process leading to a wrong,missed, or a delayed diagnosis.11In our case, the patient presented with acute severe unilateral extremity pain and was initially diagnosed with DVT by means of a lower extremity duplex US. Despite being on the correct treatment for the initial diagnosis of acute DVT, her pain steadily progressed with pain medication requirement drastically increasing to a level at which intravenous patient-controlled analgesia was administered with no or minimal pain relief. Despite repeated consultations with healthcare providers of various clinical disciplines and an atypical progression of the initial diagnosis of DVT, differential diagnosis was only achieved on day 5 of admission at which repeated imaging evaluations revealed correct diagnosis. Our approach to the case is an illustration of the anchoring bias. Anchoring is a cognitive bias that involves a clinician adhering to the initial diagnostic impression despite the appearance of new information without adequately adjusting diagnostic probabilities.12This new information could be in the forms of history, physical examination, and investigation results, which in our case was the atypical disease course not consistent with the initial diagnosis.

Diagnostic errors form a common source of patient injury and frequently include a cognitive component.11Development of insight and awareness of the known cognitive biases amongst healthcare providers is one of many proposed strategies used to reduce diagnostic errors and preventable patient injury.13

Plagiarism check

This paper has been checked twice with duplication-checking software iThenticate.

Peer review

A double-blind and stringent peer review process has been performed to ensure the integrity, quality and significance of this paper.

Author contributions

WI conceived the study and critically revised the paper for important intellectual content. WI, HA, LO and MS were responsible for literature retrieval and critically reviewed the paper. All authors approved the final version of this paper.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained the appropriate patient consent form. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understand that her name and initial will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal her identity,but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Open access statement

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Contributor agreement

A statement of “Publishing Agreement” has been signed by an authorized author on behalf of all authors prior to publication.

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics,2012.CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108.

2. Stinchcombe TE, Lee CB, Socinski MA. Current approaches to advanced-stage non- small-cell lung cancer: first-line therapy in patients with a good functional status.Clin Lung Cancer.2006; Suppl 4:S111-117.

3. Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Fallah M, et al. Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86:78-84.

4. D’Antonio C, Passaro A, Gori B, et al. Bone and brain metastasis in lung cancer: recent advances in therapeutic strategies. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2014;6:101-114.

5. Leeson MC, Makley JT, Carter JR. Metastatic skeletal disease distal to the elbow and knee.Clin Orthop Relat Res.1986;(206):94-99.

6. Miller SD. Metastatic adenocarcinoma to the distal fibula.Foot Ankle Surg. 2002;8:119-123.

7. Eggold JF, McFarland JA, Hubbard ER. Adenocarcinoma of the lung with phalangeal metastasis. A case report.J AmPodiatr Med Assoc. 1985;75:547-550.

8. Kemnitz MJ, Erdmann BB, Julsrud ME, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the lung with metatarsal metastasis. J Foot Ankle Surg.1996;35:210-212.

9. Kosteva J, Langer C. The changing landscape of the medical management of skeletal metastases in nonsmall cell lung cancer.Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:155-161.

10. Rajan P, Warner A, Quick CR. Fibular metastasis from renal cell carcinoma masquerading as deep vein thrombosis.BJU Int.1999;84:735-736.

11. Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine:analysis of 583 physician-reported errors.Arch Intern Med.2009;169:1881-1887.

12. Anchoring Bias With Critical Implications. AORN J. 2016;103:658-631.

13. Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78:775-780.