冷驯化对中缅树鼩PPARα、COXⅡ及PGC-1α基因表达量的影响

2017-02-18侯东敏章迪余婷婷王政昆高文荣朱万龙

侯东敏, 章迪, 余婷婷, 王政昆, 高文荣, 朱万龙*

(1.云南省高校西南山地生态系统动植物生态适应进化及保护重点实验室,云南师范大学生命科学学院,昆明650500; 2.云南经济管理学院,昆明650106)

冷驯化对中缅树鼩PPARα、COXⅡ及PGC-1α基因表达量的影响

侯东敏1, 章迪2, 余婷婷1, 王政昆1, 高文荣1, 朱万龙1*

(1.云南省高校西南山地生态系统动植物生态适应进化及保护重点实验室,云南师范大学生命科学学院,昆明650500; 2.云南经济管理学院,昆明650106)

为了研究冷驯化条件下中缅树鼩Tupaiabelangeri的脂肪组织是否会转化,本研究测定了冷驯化条件下中缅树鼩脂肪组织质量,脂肪转化因子过氧化物酶体增殖激活受体α(PPARα)、环氧化酶-2(COXⅡ)及过氧化物酶体增殖物受体γ共激活因子1α(PGC-1α)基因表达量的变化。结果表明:中缅树鼩冷驯化组无论是褐色脂肪组织(BAT)质量,还是大网膜白色脂肪组织(WAT)质量均较对照组显著增加(P<0.01),脂肪转化因子PPARα、COXⅡ及PGC-1α基因表达量也显著上调(P<0.01)。以上结果说明中缅树鼩WAT中PPARα、COXⅡ、PGC-1α基因表达量的增加可能诱导了WAT细胞褐变,进而向BAT细胞转化和提高BAT中解偶联蛋白1的表达。

中缅树鼩;脂肪组织;冷驯化

动物在野外生存面临许多环境因子的胁迫,尤其是在冬季,如环境温度较低和食物资源较差(Voltura & Wunder,1998)。当环境温度较低时,小型哺乳动物会表现出生理、行为等方面的适应性特征变化(Feder & Block,1991),而这往往会影响其野外的生存策略(朱万龙等,2008)。生理上,小型哺乳动物通常会在低温环境下增加产热能力,其主要的适应性产热(非颤抖性产热)发生器官是褐色脂肪组织(brown adipose tissue,BAT)。已有研究表明:低温条件下小型哺乳动物的白色脂肪组织(white adipose tissue,WAT)可以褐变,进而向BAT转化(Cypessetal.,2009;van Marken Lichtenbeltetal.,2009;Enerback,2010;Birerdincetal.,2013),从而提高其产热能力。其中几种重要的脂肪转化因子起着重要的作用,如COXⅡ和PGC-1α能诱导WAT中BAT细胞的形成(Gestaetal.,2007;Madsenetal.,2010;Vegiopoulosetal.,2010),PPARα能诱导原代BAT细胞和BAT中解偶联蛋白1(uncoupling protein 1,UCP1)的表达(Feder & Block,1991)。这3种转录因子在冷驯化条件下表达量上调,可以使WAT褐变向BAT转化,从而增加动物的产热能力(Birerdincetal.,2013)。

中缅树鼩Tupaiabelangeri主要栖息在热带、亚热带地区,为东洋界特有的小型哺乳动物。研究表明树鼩科Tupaiidae动物由南向北扩散,即支持“岛屿起源”假说(Olsonetal.,2005),而本研究组之前的研究也支持这一假说(王政昆等,1994,1995,1999;张武先等,2002)。目前,实验动物的研发趋向动物体型小型化发展,树鼩因体型较小(一般为80~150 g)、进化地位和灵长类相似、人工繁殖和饲养成本较低,近年来已被广泛用作生物、医学等科学研究的实验动物(Kawamichi & Kawamichi,1979)。本研究组先前的研究结果指出,中缅树鼩在冷驯化条件下的产热、BAT质量和UCP1含量显著增加(王政昆等,1995),那么在该环境下中缅树鼩的WAT是否会向BAT转化,导致BAT质量和UCP1含量增加,从而增加其产热能力?本研究在此假设的基础上,在冷驯化条件下测定中缅树鼩的脂肪组织质量,脂肪转录因子PPARα、COX Ⅱ及PGC-1α基因表达量,来验证低温条件下中缅树鼩的WAT是否会褐变,进而向BAT转化。

1 材料与方法

1.1 动物来源

中缅树鼩捕自云南省昆明市禄劝县的灌丛中,于云南师范大学生命科学学院动物饲养房(昆明)单笼室温饲养(温度25 ℃±1 ℃,光照12L∶12D)。饲料为标准的雏鸡饲料(昆明生产的产蛋雏鸡饲料),熟喂,自由饮水。实验动物均为成年非繁殖期个体。

1.2 动物处理

预适应1周后进行正式实验,随机分成2组:对照组和冷驯化组(每组各10只),实验前,2组动物体质量差异无统计学意义。冷驯化组在温度5 ℃±1 ℃,光照12L∶12D环境中驯化28 d;对照组在温度25 ℃±1 ℃,光照12L∶12D环境中驯化28 d。驯化期间动物可以自由取食和饮水。2组动物于28 d后断颈处死,称量其大网膜WAT和肩胛骨间BAT质量,取出皮下WAT于-80 ℃保存,用于相关脂肪转录因子基因表达量的测定。

1.3 表达量测定

1.3.1 RNA提取及纯度鉴定 皮下脂肪组织总RNA的提取与纯化根据RNApure高纯总RNA快速抽提试剂盒(BioTeke Co.)提供的方法进行。通过琼脂糖凝胶电泳进行RNA纯度和完整性检验。提取的总RNA置于-80 ℃保存。

1.3.2 cDNA第一链合成 第一链的合成以皮下脂肪组织总RNA为模板,根据FastQuant RT Kit(With gDNase)试剂盒提供的方法进行。基因组DNA的去除体系包括:2 μL 5×gDNA Buffer,4 μL 总RNA,4 μL Rnase-Free ddH2O,配制体积10 μL,混匀。离心,42 ℃孵育3 min。然后置于冰上。反转录反应体系包括:2 μL 10×Fast RT Buffer,1 μL RT Enzyme Mix,2 μL FQ-RT Primer Mix,5 μL Rnase-Free ddH2O,配制体积10 μL。将反转录反应中的Mix加到gDNA去除步骤的反应液中,充分混匀。42 ℃孵育15 min,95 ℃孵育3 min之后放于冰上,得到的cDNA低温保存。

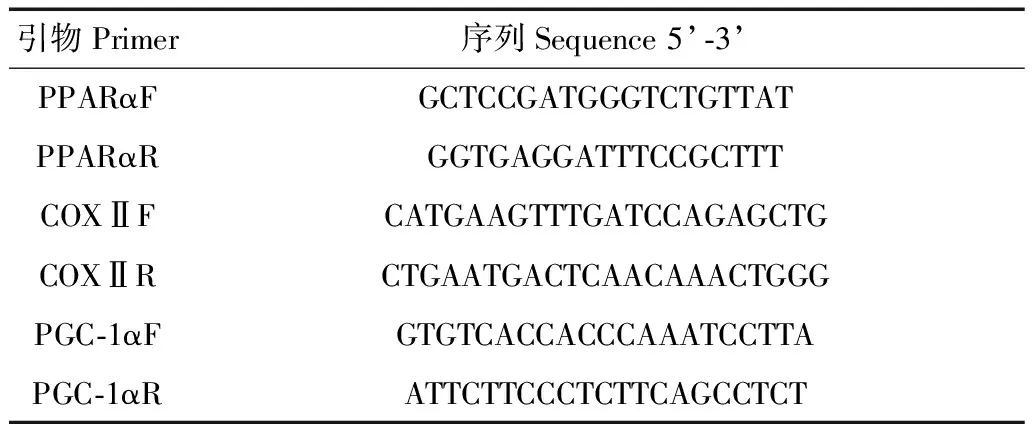

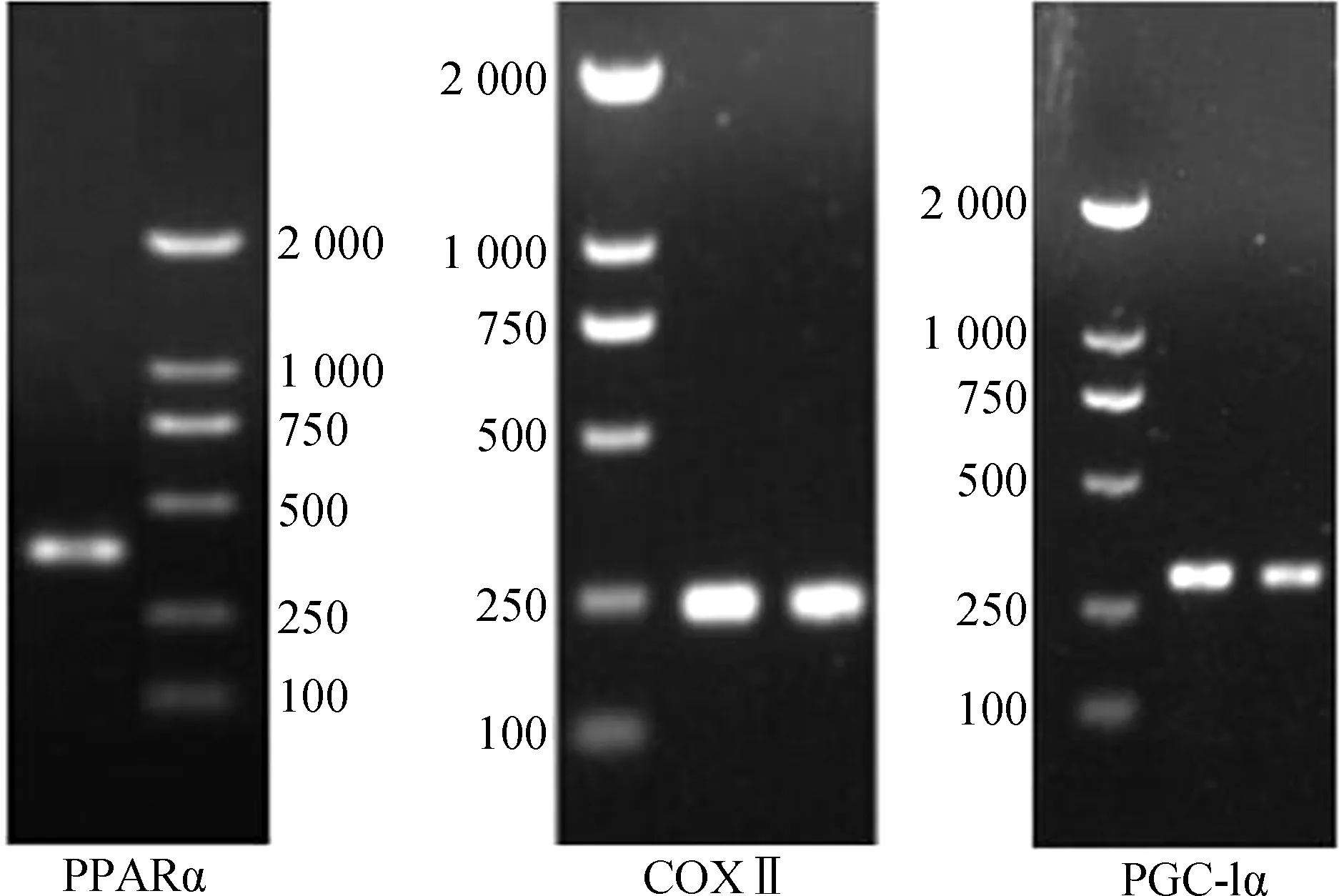

1.3.3 PPARα、COXⅡ及PGC-1α基因cDNA序列的扩增 根据已知脊椎动物PPARα、COXⅡ及PGC-1α基因氨基酸保守序列设计引物(表1)(章迪等,2014)。以上述cDNA第一链为模板进行RT-PCR,扩增条件均为:95 ℃变性4 min;95 ℃ 30 s,54~56 ℃ 1 min,72 ℃ 40 s,37个循环;72 ℃延伸10 min。扩增体系为50 μL: 1 μL模板(10 ng·μL-1),1 μL上游引物(10 pmol·μL-1),1 μL下游引物(10 pmol·μL-1),4 μL dNTP(10 mmol·L-1,pH8.0),1 μL Taq酶(4 U·μL-1),5 μL 10×PCR Buffer(Mg2+),37 μL ddH2O。扩增产物效果见图1。

1.3.4 实时荧光定量PCR(FQ-PCR) 模板cDNA用ABI-7000TM实时荧光PCR仪进行扩增,同时检测荧光信号。FQ-PCR反应体系依照SYBR Green Realmaster Mix试剂盒说明进行配制。反应体系为20 μL:9 μL SYBR Green Realmaster Mix,0.5 μL F引物 (12.5 μmol·L-1),0.5 μL R引物(12.5 μmol·L-1),0.5 μL cDNA 模板,9.5 μL RNase ddH2O。扩增条件为第一步94 ℃ 2 min,第二步94 ℃ 15 s,第三步60 ℃ 35 s,第二步到第三步重复37个循环。1个基因的每个样本均进行3次实时荧光定量平行重复,采用的数据为3次平行测定结果的平均值(朱万龙等,2014)。内参基因引物F:5’-GAGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3’;引物R:5’-CATCTGCTGGAAGGTGGACA-3’。

表1 扩增中缅树鼩PPARα、COXⅡ、PGC-1α引物

图1 中缅树鼩PPARα、COXⅡ、PGC-1α的PCR扩增电泳图

Fig. 1 PCR electrophoresis of PPARα, COXⅡ and PGC-1α inTupaiabelangeri

1.3.5 2-△△CT相对定量法 目的基因的转录表达水平采用2-△△CT相对定量法进行计算,用内参基因作均一化处理,ΔΔCT=(CT目的基因-CT内参基因)处理组-(CT目的基因-CT内参基因)对照组,2-△△CT可反映出用内参基因均一化处理后,该样本目的基因的初始模板量相对于对照样本的表达倍数(差异)(Livak & Schmittgen,2001;Crottetal.,2007;Ornatowskaetal.,2007)。对于对照组样本,ΔΔCT=0,2-△△CT=1。而对于冷驯化组样本,若2-△△CT>1,说明该基因表达上调;若2-△△CT<1,说明该基因表达下调。

1.4 统计分析

实验数据的统计分析采用SPSS 16.0处理。采用独立样本t检验对不同组中WAT、BAT质量和相关脂肪转化因子表达量的差异进行处理。结果以平均值±标准误(Mean±SE)表示,其中P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义,P<0.01表示差异有高度统计学意义。

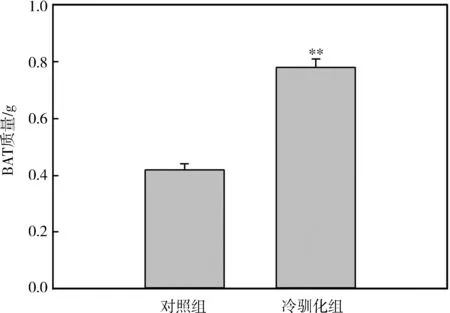

2 结果

实验前,对照组和冷驯化组中缅树鼩的体质量分别为103.56 g±2.32 g和102.89 g±3.02 g,2组体质量差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。冷驯化28 d后,2组脂肪组织质量差异有高度统计学意义(BAT:t=-6.92,P<0.01,图2;WAT:t=-5.56,P<0.01,图3),冷驯化组显著高于对照组,其中BAT质量为冷驯化组较对照组升高了85.71%,WAT质量则增加了14.14%。

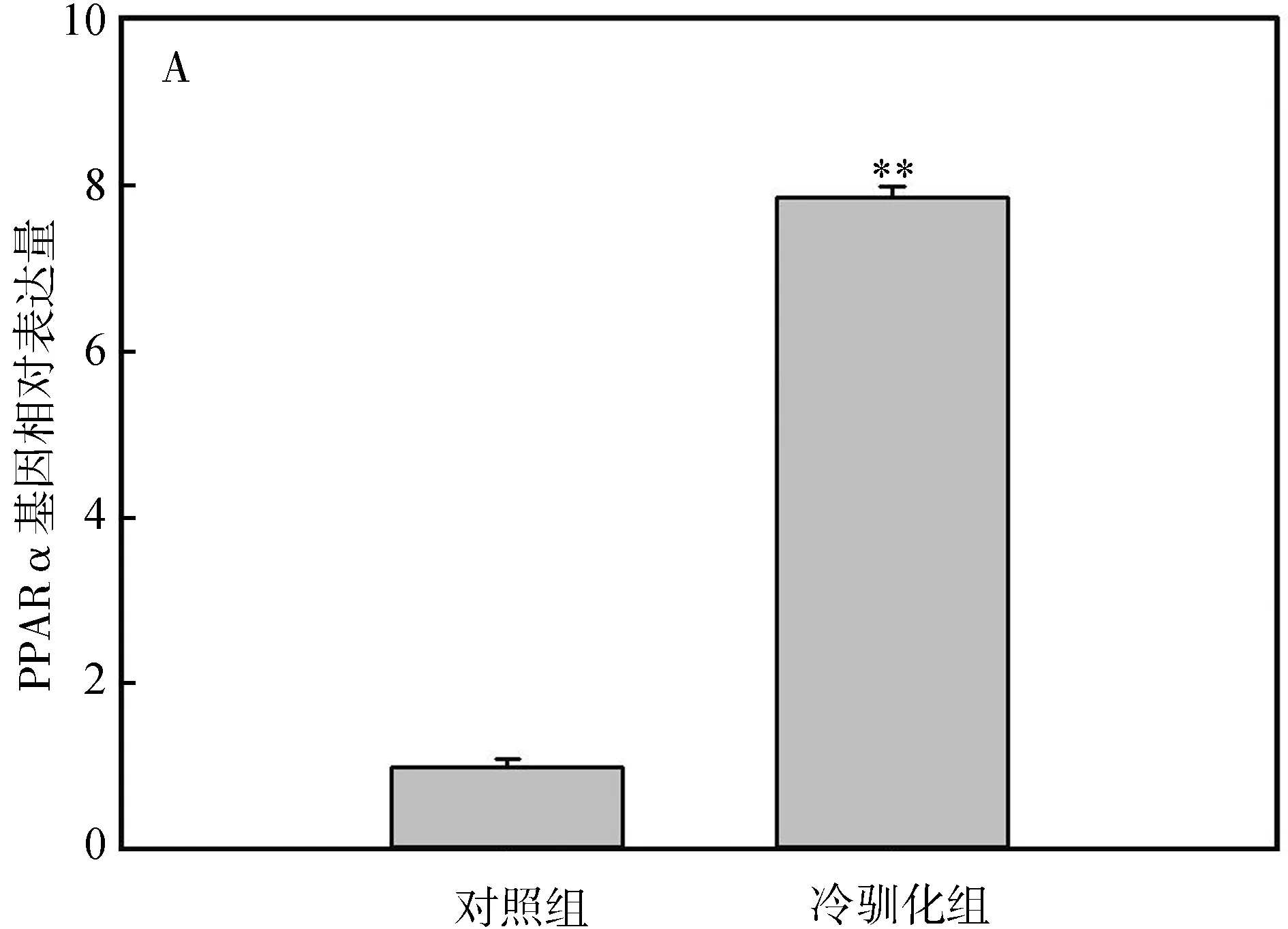

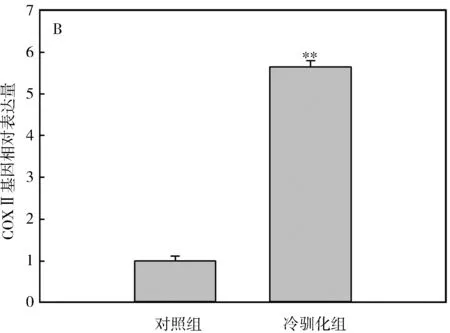

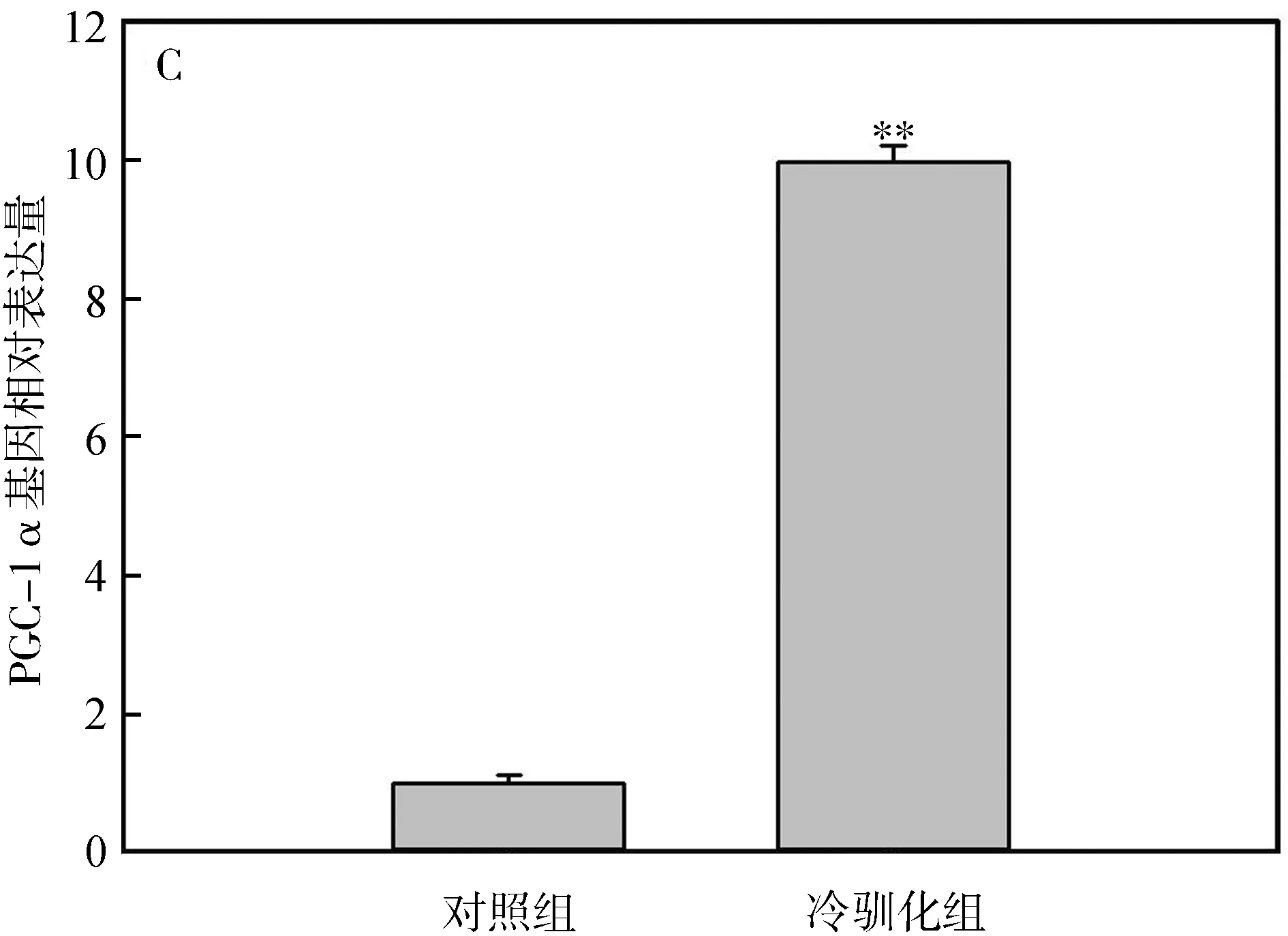

冷驯化28 d后,中缅树鼩PPARα、COXⅡ和PGC-1α基因表达量显著高于对照组(PPARα:t=-6.36,P<0.01,图4:A;COXⅡ:t=-7.44,P<0.01,图4:B;PGC-1α:t=-2.87,P<0.01,图4:C),其中冷驯化组PPARα、COXⅡ和PGC-1α基因表达量分别是对照组的7.68倍、5.65倍和9.98倍。

图2 冷驯化对中缅树鼩褐色脂肪组织质量的影响

图3 冷驯化对中缅树鼩白色脂肪组织质量的影响

3 讨论

栖息环境不同,小型哺乳动物在低温条件下的体质量变化模式也不同,有些动物体质量变化不明显,如小林姬鼠Apodemussylvaticus(Klausetal.,1988)和非洲刺毛鼠Acomyscahirinus(Khokhlovaetal.,2001),而有些动物体质量增加,如环颈旅鼠Dicrostonyxgroenlandicus和金黄仓鼠Mesocricetusauratus(Nagy & Negus,1993)。在本研究中,冷驯化组中缅树鼩大网膜WAT质量显著增加,和本研究组之前研究结果中中缅树鼩的体质量变化趋势一致,说明在冷驯化过程中,中缅树鼩体质量的增加可能和体内WAT质量的增加有关,当然,WAT的增加也和动物在该驯化条件下食物充足、不受限制有关(王政昆等,1995)。动物在低温条件下,一般会增加其产热能力来维持生存(Hayes & Chappell,1986)。本研究中,中缅树鼩在冷驯化条件下,BAT质量较对照组显著增加,说明中缅树鼩在该条件下增加BAT质量,从而增加UCP1的含量,最终增加非颤抖性产热来应对低温胁迫,这和本研究组先前的研究结果一致(Zhuetal.,2012)。BAT的质量增加可能是中缅树鼩自身在冷驯化条件下的BAT增生,还有可能是WAT褐变向BAT的转化而来。

图4 冷驯化对中缅树鼩PPARα(A)、COXⅡ(B)和PGC-1α(C)基因表达量的影响

脂肪转化因子PPARα、COXⅡ及PGC-1α在WAT向BAT的转变中具有重要作用(Madsenetal.,2010)。PPARα表达量的上调能诱导原代BAT细胞增生和UCP1的高表达(Barberaetal.,2001;Tongetal.,2005)。COXⅡ对于WAT中诱导形成BAT细胞是必需的,有研究表明WAT中诱导出现的BAT细胞中UCP1的表达依赖于COXⅡ(Madsenetal.,2010)。PGC-1α表达过高会使小鼠Musmusculus的WAT中具有UCP1阳性表达的BAT细胞增加(Puigserveretal.,1998)。本研究中,冷驯化28 d后,PPARα mRNA、COXⅡ mRNA及PGC-1α mRNA的基因表达量显著增加,这可能诱导了中缅树鼩WAT中BAT细胞的形成,或者使脂肪组织中UCP1含量增加,从而增加其在冷环境中的产热能力。

总之,中缅树鼩在冷驯化条件下通过增加脂肪转录因子的基因表达量,可能使得WAT细胞褐变增加UCP1表达量,促进了BAT细胞的分化和代谢,弥补中缅树鼩在冷环境中适应性产热的不足,以抵抗低温环境。

王政昆, 李庆芬, 孙儒泳. 1995. 中缅树鼩的非颤抖性产热及细胞呼吸特征[J]. 动物学研究, 16(3): 408-414.

王政昆, 李庆芬, 孙儒泳. 1999. 光周期和温度对中缅树鼩产热能力的影响[J]. 动物学报, 45(3): 287-293.

王政昆, 孙儒泳, 李庆芬. 1994. 中缅树鼩静止代谢率的研究[J]. 北京师范大学学报(自然科学版), 30(3): 408-414.

张武先, 王政昆, 徐伟江. 2002. 冷驯化对中缅树鼩能量代谢的影响[J]. 兽类学报, 22(2): 123-129.

章迪, 张浩, 朱万龙. 2014. 中缅树鼩PRDM16、BMP7、PPARα、COXⅡ及PGC-1α基因的扩增研究[J]. 生物过程, 4(3): 52-60.朱万龙, 蔡金红, 张麟, 等. 2014. 中缅树鼩体质量、血清瘦素和下丘脑神经肽表达量的季节性变化[J]. 生物学杂志, 31(3): 33-37.

朱万龙, 王海, 贾婷, 等. 2008. 冷驯化对大绒鼠和高山姬鼠肝脏线粒体呼吸的影响[J]. 四川动物, 27(3): 371-377.

Barbera MJ, Schluter A, Pedraza N,etal. 2001. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activates transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein-1 gene: a link between regulation of the thermogenic and lipid oxidation pathways in the brown fat cell[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(2): 1486-1493.

Birerdinc A, Jarrar M, Stotish T,etal. 2013. Manipulating molecular switches in brown adipocytes and their precursors: a therapeutic potential[J]. Progress in Lipid Research, 52(1): 51-61.

Crott JW, Liu Z, Choi SW,etal. 2007. Folate depletion in human lymphocytes up-regulates p53 expression despite marked induction of strand breaks in exons 5-8 of the gene[J]. Mutation Research, 626(1-2): 171-179.

Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G,etal. 2009. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 360(15): 1509-1517.

Enerback S. 2010. Human brown adipose tissue[J]. Cell Metabolism, 11(4): 248-252.

Feder ME, Block BA. 1991.On the future of animal physiological ecology [J]. Functional Ecology, 5(2): 135-144.

Gesta S, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. 2007. Developmental origin of fat: tracking obesity to its source[J]. Cell, 131(2): 242-256.

Hayes JP, Chappell MA. 1986. Effects of cold acclimation on maximum oxygen consumption during cold exposure and treadmill exercise in deer micePeromyscusmaniculatus[J]. Physiological Zoology, 59(4): 453-459.

Kawamichi T, Kawamichi M. 1979. Spatial organization and territory of three shrews (Tupaiaglis)[J]. Animal Behavior, 27(2): 381-393.

Khokhlova I, Krasnov BR, Shenbrot GI,etal. 2001. Body mass and environment: a study in Negev rodents[J]. Israel Journal Zoology, 47(1): 1-13.

Klaus S, Heldmaier G, Ricquier D. 1988. Seasonal acclimation of bank voles and thermogenic properties of brown adipose tissue mitochondria[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 158(2): 157-164.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-△△CTmethod[J]. Methods, 25(4): 402-408.

Madsen L, Pedersen LM, Lillefosse HH,etal. 2010. UCP1 induction during recruitment of brown adipocytes in white adipose tissue is dependent on cyclooxygenase activity[J]. PLoS ONE, 5(6): e11391. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0011391.

Nagy TR, Negus NC. 1993. Energy acquisition and allocation in male collared lemmingsDicrostonyxgroenlandicus: effects of photoperiod, temperature, and diet quality[J]. Physiological Zoology, 66(4), 537-560.

Olson LE, Sargis EJ, Martin RD. 2005. Intraordinal phylogenetics of tree shrews (Mammalia: Scandentia) based on evidence from the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene[J]. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 35(3): 656-673.

Ornatowska M, Azim AC, Wang X,etal. 2007. Functional genomics of silencing TREM-1 on TLR4 signaling in macrophages[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 37(6): L1377-L1384.

Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW,etal. 1998. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis[J]. Cell, 92(6): 829-839.Tong Y, Hara A, Komatsu M,etal. 2005. Suppression of expression of muscle-associated proteins by pparalpha in brown adipose tissue[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communication, 336(1): 76-83.

van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM,etal. 2009. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 360(15): 1500-1508.

Vegiopoulos A, Muller-Decker K, Strzoda D,etal. 2010. Cyclooxygenase-2 controls energy homeostasis in mice bydenovorecruitment of brown adipocytes[J]. Science, 328(5982): 1158-1161.

Voltura MB, Wunder BA. 1998. Effects of ambient temperature, diet quality, and food restriction on body composition dynamics of the prairie vole,Microtusochrogaster[J]. Physiological Zoology, 71(3): 321-328.

Zhu WL, Jia T, Huang CM,etal. 2012. Changes of energy metabolism, thermogenesis and body mass in the tree shrew (Tupaiabelangerichinensis) during cold exposure[J]. Italian Journal of Zoology, 79(2): 175-181.

Effect of Cold Exposure on the Expressions of PPARα, COXⅡ and PGC-1α inTupaiabelangeri

HOU Dongmin1, ZHANG Di2, YU Tingting1, WANG Zhengkun1, GAO Wenrong1, ZHU Wanlong1*

(1.Key Laboratory of Ecological Adaptive Evolution and Conservation on Animals-Plants in Southwest Mountain Ecosystem of Yunnan Province Higher Institutes College, School of Life Sciences, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming 650500, China; 2. Yunnan College of Business Management, Kunming 650106, China)

In order to investigate whether the adipose tissue ofTupaiabelangeriwould be transformed under cold acclimation, the mass of adipose tissue, changes of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), cyclooxygenase-2 (COXⅡ) and peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1 (PGC-1α) genes were measured in the present study. The results showed that mass of brown adipose tissue and omental white adipose tissue, the mRNA expressions of PPARα, COXⅡ and PGC-1α genes were increased extreme significantly under cold exposure compared with control (P<0.01). And these indicated that the increased expressions of PPARα, COXⅡ and PGC-1α genes under cold condition may cause the transformation of white adipose tissue to browning beige adipocyte, which then transformed to brown adipose tissue and increase the level of uncoupling protein 1 in brown adipose tissue.

Tupaiabelangeri; adipose tissue; cold exposure

2016-08-31 接受日期:2016-11-18

国家自然科学基金项目(31660121); 联合支持国家计划项目(2015GA008); 云南省科技计划重点项目(2016FA045)

侯东敏(1992—), 男, 硕士研究生, 研究方向:动物生理生态, E-mail:houl92@163.com

*通信作者Corresponding author, 男, 副教授, 主要从事动物生理生态研究, E-mail:zwl_8307@163.com

10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20160232

Q95-33

A

1000-7083(2017)01-0034-05