High dose niacin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a pilot study

2017-01-18JIANGHaoMDLIChangyiProf

JIANG Hao. MD, LI Chang-yi. Prof.

(Department of Dermatological and Clinical Research, The First Affliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanning 530023, Guangxi, China)

High dose niacin in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a pilot study

JIANG Hao1. MD, LI Chang-yi1. Prof.

(Department of Dermatological and Clinical Research, The First Affliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanning 530023, Guangxi, China)

Introduction Acne patients are frequently associated with abnormal lipid profle. It may be useful to apply high dose of niacin that regulates the lipid profle along with acne treatment. There is no report about high dose of niacin in treatment of acne. Objective To evaluate the therapeutic effect and safety of high-dose niacin in acne vulgaris.MethodsAcne patients were randomly allocated to two treatment groups. Both groups were treated orally with the tablets for 12 weeks; the niacin group at an increasing dose of niacin tablet: 2000 mg (40 mg/kg/d). The control group (nicotinamide group) at a dose of nicotinamide tablet: 600 mg (10 mg/kg/d). All patients were asked not to consume certain foods such as milk and alcohol. A high-protein, low-fat and low-glycemic-load diet was recommended in both groups. Results A total of 108 patients were fnished the study. Niacin group: 56 patients; control group: 52 patients. After 12 weeks of treatment, niacin and nicotinamide caused improvement in acne patients. Percentage Improvement in the niacin group (82.37±7.837) %was signifcantly higher than in the nicotinamide group (63.19±10.18)%,P<0.01. The number of successful cases in the niacin group was signifcantly higher than in the nicotinamide group after 12 weeks of treatment, (χ2= 10.55,P<0.01). Conclusions High dose niacin can really do it work in treatment of acne vulgaris. The therapeutic effcct of High dose of niacin in treatment of acne vulgaris is more effective than nicotinamide.

niacin; nicotinamide; acne vulgaris; acne; Vitamin B3

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous glands resulting from androgen-induced,increased sebum production, altered keratinisation,and inflammation[1]. It has been reported that abnormal lipid oxidation plays a major role in acne inflammation[2-4].Acne patients, males and females, had signifcantly low plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels. Plasma triglycerides and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels in severe cases of acne were shown to be significantly elevated compared with those in healthy controls[5]. Acne patients are frequently associated with abnormal lipid profle[6]. Lipoprotein (a) [LP(a)] in male and female patients with mild, moderate and severe acne was signifcantly higher than in the healthy control group. The constituent ratio of male and female patients with TC, TG, LDL-C and LP(a) over the normal range were significantly higher than in the healthy control group[6]. Obese females with acne, compared with obese females without acne and nonobese subjects, had significantly higher serum triglycerides,lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein-B (apo-B)[7]. Hyperlipidemia is an important risk factor for atherosclerosis[8-9]. Acne patients have significant changes in the plasma lipid profle that should be considered in the pathogenesis as well as in the treatment of acne.

Nicotinamide have been used for the treatment of acne vulgaris for more than 50 years, and several recent studies have investigated its effcacy and safety[10-13]. Nicotinamide is involved in numerous oxidation–reduction reactions in mammalian biological systems, essentially acting as an antioxidant[14]. The mechanism of action of nicotinamide in the treatment of acne vulgaris includes an anti-inflammatory effect via inhibition of leukocyte chemotaxis, lysosomal enzyme release, a bacteriostatic effect against Propionibacterium acnes, and decreased sebum production. In the clinical studies, niacinamide significantly decreased hyperpigmentation and increased skin lightness; the mechanism occurs by inhibiting melanosome transfer from melanocytes to keratinocytes[13-14]. Other possible mechanisms involve suppression of vascular permeability and inflammatory cell accumulation, aswell as protection against DNA damage[15]. Therapeutic effect of nicotinamide in control group may avoid Medical disputes and ease the doctor-patient relationship of the study.

Niacin, also known as nicotinic acid, though it is converted to nicotinamide in vivo, niacin and nicotinamide are different compounds[16-17]. Niacin has different pharmacological effects to nicotinamide. Serum lipid levels can be modifed by niacin and skin capillaries can be dilated by niacin to cause flushing. Nicotinamide does not have the same lipid-modifying effects as niacin. These special pharmacological effects of niacin and nicotinamide may produce different therapeutic results in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Although serious hepatic toxicity from niacin administration has been reported, it is largely confined to the use of slow-release formulations given as unregulated nutritional supplements[18-19]. Laboratory abnormalities that are usually small (≤10%) and clinically unimportant include increased prothrombin time, increased uric acid, and decreases in platelet count and serum phosphorus. The perception of niacin side effects is often greater than the reality. The therapeutic effects of immediate-release niacin in the treatment of acne are observed in this study.

Materials and Methods

Ethical committee clearance was obtained before undertaking this study, and informed consent was also obtained from all subjects. Clinical data were collected from outpatients at the Department of Dermatology, the frst affliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Chinese Medicine, China. Patients with mild, moderate-to-severe, symmetric facial acne vulgaris were recruited.

Random numbers were generated by computer, and type of treatment programs were written on cards sealed in opaque envelopes. Acne patients can select a envelope with random number, in which the Patient’ information was filled and treatment programs were implemented according to the clinical manifestation of patient.

Exclusion criteria were therapy of oral isotretinoin, antibiotics, topical agents, or phototherapy during the 4 weeks preceding the trial; pregnancy or lactation; patients with a history of allergies, or heart, liver, or kidney dysfunction; and those who could not tolerate the side effects of niacin.

The niacin group was treated orally with niacin tablets. On day 1, the patients received 100 mg, four times daily (qid); on day 2, 200 mg, qid; on day 3, 300 mg, qid; on day 8, 400 mg, qid; on day 9, 500 mg, qid. The niacin dosage was gradually increased to 2000 mg/d (500 mg, Qid; 40mg/kg/d) in the second week. The nicotinamide group was control group, the patients were treated orally with nicotinamide tablets at a dosage of 200 mg tid (600 mg/d, 10 mg/kg/d). Both niacin and nicotinamide group were also treated with folic acid(10mg, tid), vitamin B6(20mg, tid), vitamin B12(50μg, bid). A high-protein, low-fat, low-glycemic-load diet and drinking more water was recommended in both group. Drug treatment time was 3 months.

All patients were asked not to consume certain food, such as chili, milk, beef, fried food (eg., fried chicken, French fries, grilled steak), beer, or liquor during treatment. The acne patients and their parents in both groups were patiently informed that the drugs may cause fushing but that it is not an allergic reaction. No antibiotics were used in either group.

Efficacy and safety assessment

Hayashi scoring in assessing the severity in acne patients was used[20]. In 2008, Hayashi et al. used lesion counting to classify acne lesions into four groups[20]. They classified acne based on the number of infammatory eruptions on half the face as 0-5: mild; 6-20: moderate; 21-50: severe; and more than 50: very severe.

Acne lesion counts were done visually twice a month to evaluate changes in the number of inflammatory lesions (papules or pustules) and to check any side effects that might appear systemically or topically. The total of inflammatory acne and non inflammatory acne lesion on the face, back, chest and back neck (Acne Keloidalis Nuchae[21]) of the body were scored to assess the progress of acne. After 12 weeks of treatment, success was assessed according to the Investigator's Global Assessment scale[22-23]: clear—residual hyperpigmentation and erythema may be present, the facial skin is clear and almost clear; almost clear: a few scattered comedones and a few (≤5) small papules (improving) on face[22-23]; clear and almost clear is successful case. Not clear—Patient has greatly improved after treatment, but the facial skin is not clear, comedones, mild papules (new infammatory lesions) can be found on the face, not clear case.

The percentage improvement in lesion count was calculated with the following equation:

[(baseline lesion counts –lesion counts after weeks treatment) / baseline lesion counts]×100%.

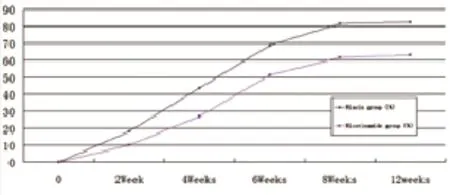

Percentage improvements:*, The mean percentage improvement in the niacin group was signifcantly higher than in the nicotinamide group, P<0.01;Clear and Not clear Cases after 12 weeks of treatment:◆, According to the Investigator's Global Assessment scale, the constituent ratio of Clear cases in the niacin group was signifcantly higher than in the nicotinamide group after 12 weeks of treatment, χ2=10.55, P<0.01

Larger inflammatory papules, pustules, symmetric acne and cysts equal to or larger than 6 mm in diameter were counted as two acne lesions.

Side effects and tolerance of niacin would be ascertained by asking the patient at each visit about any abnormal effect that appeared throughout the course of treatment. Also at each visit, the investigator rated the severity of the niacin symptoms of flushing (warmth, itching, redness, or tingly feeling on the skin) on a scale ranging from 0 (absence), 1 (mild: comfortable), 2 (moderate: uncomfortable but tolerable), to 3 (severe: uncomfortable and intolerable)[22]. The laboratory tests included complete blood counts and liver function at the beginning of and after treatment.

Statistical analysis

The homogeneity of variance test was used to compare patients’ ages and total acne score before treatment. Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare the signifcance of the mean percentage improvement between the treatment groups at different times. The chi-squared (χ2) test was used to compare the treatment success rates in the niacin and nicotinamide groups after 12 weeks of treatment. For all comparisons, a signifcance level of 0.05 (P<0.05) was used. Results were represented as the mean ± standard deviation (x¯±s).

Results Patient disposition and baseline characteristics (Table 1)

A total of 112 patients (age range, 14 to 30 years) were randomised into two treatment groups, the niacin group and the nicotinamide group. Three patients dropped out of the niacin group and one dropped out of the nicotinamide group. The niacin group included 56 patients (23 male, 33 female, with a mean age of 20.5714±4.12 years; the nicotinamide group had 52 patients (25 male and 27 female; mean age, 19.9231±3.95 years). Both groups were of similar size and well matched at baseline with respect to age, sex, duration.

Efficacy evaluation (Table 1 and Figure 1)

Acne patients had their niacin dosages increased 2000 mg (500 mg, tid) by the two weeks of treatment. Acne lesion on the face, back, chest and back neck (Acne Keloidalis Nuchae) of the body are healed by niacin treatment. Improvement in the niacin group was more than 80% after 12 weeks’ treatment. Response of the acne lesions to niacin was superior to that of nicotinamide and this difference was statistically signifcant (P<0.01). Improvement in the niacin group increased rapidly, and it was signifcantly higher than in the nicotinamide group for several weeks (P<0.01) (Table 1,Figure 1). Improvement in the niacin group was significantly higher than in the nicotinamide group over different treatment periods (P<0.01) (Table 1). The number of successful cases in the niacin group was significantly higher than in the nicotinamide group after 12 weeks of treatment (Table 1). Figure 3 to 6 showsthe photos of a patient before, during, and after 3 months of niacin treatment (500 mg, Qid).

Figure 1 Percentage Improvement of niacin and nicotinamide

Figure 2 Niacin fushing Changes with treatment period

Safety evaluation (Figure 2)

Flushing was experienced by all the patients (100%) in the niacin group. It was frequently accompanied by heat, itching, or a prickly sensation on the upper part of the body. These symptoms appeared at the same time. Flushing appears 10-30 min after taking niacin (35.7% experience it in 10 min; 37.5%, in 15 min; 26.78%, in 20 min), and it usually lasts for about 20 to 30 min (82.14%), though it can sometimes last up to 1 h (17.85%) during the frst 2 weeks of treatment. Flushing (prickly, hot, and itching) was transient, peaking during the second week of treatment and decreasing over time. After 4 weeks of treatment, the symptoms of niacin flushing had disappeared (Figure 2). Seven patients (12.5%) experienced mild stomach discomfort (dull ache, abdominal distension) after taking niacin before a meal, but these symptoms were relieved by drinking water and eating some food. Four patients (7%) reported dry skin on cold winter days.

An inflammatory acne lesion developed into a large cyst on the face of a patient with a severe case during early niacin treatment. The lesion caused no further deterioration, but it did not respond readily to the niacin until it had fully liquefed and softened. The mixture of blood and pus in the cysts was drained by needle puncture. Three patients discontinued treatment because they or their families feared the side effects of highdosage niacin treatment. There were no trends in haematology or liver functional parameters indicative of any toxic systemic effect of the niacin or the nicotinamide.

Figure 3 A patient before niacin treatment

Figure 5 The patient of 8 weeks of niacin treatment

Figure 4 The patient after 4 weeks of niacin treatment.

Discussion

This was a pilot clinical study to evaluate high-dose niacin in the treatment of acne patients. Improvement in the niacin group was signifcantly higher than in the nicotinamide group (P<0.01) over the period treatment. Acne Keloidalis Nuchae (AKN) involves the hair follicles of the occipital base of the skull and neck. AKN and acne vulgaris were improved; The papule inflammation was subsided and disappeared, and the patients’ skin appeared smooth after 12 months of niacin treatment. The study showed that high dose niacin has beneficial effects in the treatment of acne (include sever acne and AKN). Nicotinamide has no vasodilator effect,so it does not produce flushing of the skin. It takes weeks for nicotinamide to take a gradual effect on the inflammatory acne lesions. Although nicotinamide can do it work in treatment of acne, new infammatory lesions can be more frequently found during nicotinamide treatment. Acne lesions of most patients do not clear after 12 weeks of nicotinamide treatment. Nicotinamide in treatment of acne patients of control group can avoid Medical Dispute.

Acne vulgaris is a multifactorial disease. It is reported that certain foods are aggravating factors for acne[24-25]. It is theorised that diet directly or indirectly influences thepathogenesis of acne vulgaris and the therapeutic effect of medicine[23-24]. New acne lesions can always be found in patients who take milk, beef, fried food, or alcohol even they are in treatment. Therefore, the acne patients in this study were urged to not consume these foods to prevent new infammatory acne eruptions and improve the therapeutic effect. Instead, a highprotein(at least one egg per day), low-fat, and low-glycemicload diet[26]was recommended during treatment. Acne lesions are diffcult to be cured unless patients have protein diet every day. Improvement in acne was more than 80% after 3 months’treatment with niacin combined with a high-protein diet and limitation of certain foods and alcohol.

Niacin flushing (itching, warmth, and other related symptoms) appears about 10 min after niacin ingestion and lasts for about 30 min. Flushing as a special side effect plays an important role in strengthening the pharmacological functions of niacin[27]. The pain symptoms of some acne lesions were rapidly relieved along with skin flushing. Many patients get instant therapeutic effect after the frst niacin fushing: the acne lesions are dissipating and disappearing. Inflammatory acne lesions subsided after 8 weeks’ treatment, and the small pustules and papules became dark red and disappeared without leaving a scar after 12 weeks. However, excessive flushing can be uncomfortable—even frightening—if the patient is not prepared for it. In one patient having severe acne, inflammatory acne developed into a cystic lesion after excessive fushing early in a high-dose niacin treatment. The large cyst contained a mixture of blood and pus, and it is suggested that excessive flushing might cause tiny blood vessels rupture and haemorrhage within the acne lesion. A medical doctor or a nurse must patiently explain the niacin flushing and gradually increase the dose of oral niacin before treatment in order to avoid excessive fushing. After 4 weeks’treatment with a consistent dose of niacin, the symptoms of flushing become very mild in most patients and some no longer had fushing.

In this study, the niacin dose was 2000 mg/d. There were no trends in haematology or blood chemistry parameters indicative of a systemic toxic effect of niacin treatment. Mild stomach discomfort (stomachache, bloating) occurred in a few patients, but taking niacin with meals or drinking warm water may relieve the side effects. Drinking more water may promote uricosuric effect of body. The other side effect of niacin, Acanthosis nigricans proliferation, was not found in this research.

Improvement in the niacin group was signifcantly higher than that of the control group during treatment (P<0.01), possibly because niacin has the pharmacological effect of modifying lipids[28]and causing mild cutaneous flushing, thus differing from nicotinamide. We have insufficient evidence to prove that the secretion of sebaceous glands can be diminished by niacin, but some patients felt dry and noted reduced sebum on the facial skin after several weeks’ oral niacin, possibly due to the serum lipid–regulating effects of that vitamin. Niacin is the only one drug of regulating plasma lipoprotein(a) level. Pharmacological doses of niacin dilate the capillaries, promote micro-circulation, and increase drug concentration around the lesion, by which strengthen the pharmacological effect.

Weaknesses of the research were:①The number of patients in the pilot study was small.②Very severe Acne patients and Acne Inversa need prolonged treatment and increased niacin dosage, but the dosage for patients in this study was 2000 mg/d. Niacin dose in treatment of very severe acne and patients associated with hyperlipidemia can be increasing to more higher(≥3000 mg/d).③Plasma Uric acid were not detected before and after treatment. But the renal functions of acne patients in both groups are normal.④We have no enough experience in treatment of acne by niacin.

The data support the fact that high doses of niacin(≥40 mg/kg/d) are more effective than nicotinamide group for the treatment of acne. High dose niacin can really do it work in treatment of acne vulgaris. It is safe and it is tolerated by patients with gradually increasing the dosage. A high-protein, low-fat, and low-glycemic-load diet may benefit patients with acne. Although high dose of niacin treatment of acne needs further study, its low cost and safety argues for wider used in the treatment of acne vulgaris.

[1]Hywel C Williams,Robert P Dellavalle,Sarah Garner.Acne vulgaris[J].Lancet,2012,379: 361–372.

[2]Al-Shobaili HA,Alzolibani AA,Al Robaee AA,Meki AR,Rasheed Z. Biochemical markers of oxidative and nitrosative stress in acne vulgaris: correlation with disease activity[J].J Clin Lab Anal, 2013,27(1):45-52.

[3]Sarici G,Cinar S,Armutcu F,Altinyazar C,Koca R,Tekin NS.Oxidative stress in acne vulgaris[J].J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol, 2010,24(7):763-767.

[4]Arican O,Kurutas EB,Sasmaz S. Oxidative stress in patients with acne vulgaris[J].Mediators Infamm,2005,14,2005(6):380-384.

[5]Zeyad El-Akawi,Nisreen Abdel-Latif,Khalid Abdul-Razzak,Mustafa Al-Aboosi.The relationship between blood lipids profle and acne[J]. J Health Sci,2007,53(5): 596-599.

[6]Jiang Hao,Li CY,Zhou L,Lu B,Lin Y,Huang X,Wei B,Wang Q,Wang L,Lu J. Acne patients frequently associated with abnormal plasma lipid profle[J].J Dermatol,2015,42(3):296-299.

[7]Abulnaja KO.Changes in the hormone and lipid profile of obese adolescent Saudi females with acne vulgaris[J].Braz J Med Biol Res.2009 Jun;42(6):501-505.

[8]Mason CM,Doneen AL. Niacin-a critical component to the management of atherosclerosis: contemporary management of dyslipidemia to prevent,reduce,or reverse atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease[J].J Cardiovasc Nurs, 2012 Jul-Aug;27(4):303-316.

[9]Niren NM. Pharmacologic doses of nicotinamide in the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions: a review[J]. Cutis,2006,77(1 Suppl):11-16.

[10]Niren NM,Torok HM. The Nicomide Improvement in Clinical Outcomes Study (NICOS): results of an 8-week trial[J].Cutis, 2006,77(1 Suppl):17-28.

[11]Grange PA,Raingeaud J,Calvez V,et al. Nicotinamide inhibits Propionibacterium acnes–induced IL-8 production in keratinocytes through the NF-kappaB and MAPK pathways[J].J Dermatol Sci, 2009,56(2):106-112.

[12]Gehring W.Nicotinic acid/niacinamide and the skin[J].J Cosmet Dermatol,2004,3(2):88-93.

[13]Otte N,Borelli C,Korting HC.Nicotinamide - biologic actions of an emerging cosmetic ingredient[J].Int J Cosmet Sci, 2005,27(5): 255-261.

[14]Fivenson DP.The mechanisms of action of nicotinamide and zinc in infammatory skin disease[J]. Cutis,2006,77(1 Suppl):5-10.

[15]Surjana D,Halliday GM,Damian DL. Role of nicotinamide in DNA damage,mutagenesis,and DNA repair[J]. J Nucleic Acids,2010,2010:157591.

[16]P Jaconello. Niacin versus niacinamide[J].CMAJ,1992,147(7): 990.

[17]Mason CM,Doneen AL. Niacin-a critical component to the management of atherosclerosis: contemporary management of dyslipidemia to prevent,reduce,or reverse atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease[J].J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2012 Jul-Aug; 27(4):303-16.

[18]McKenney J. Niacin for dyslipidemia: considerations in product selection[J].Am J Health Syst Pharm, 2003 May 15;60(10):995-1005.

[19]John R. Guyton,Harold E. Bays. Safety Considerations with Niacin Therapy[J].Am J Cardiol,2007.99(6):22-31.

[20]Hayashi N,Akamatsu H,Kawashima M; Acne Study Group. Establishment of grading criteria for acne severity[J].J Dermatol. 2008 May;35(5):255-260.

[21]L Enrique,C Tania,U Veronica,L Andrea,GJ Carlos. Acne keloidalis nuchae in Latin American women[J]. Int J Dermatol,2015,54(5): e183-e185.

[22]Thiboutot D,Pariser DM,Egan N,Flores J,Herndon JH Jr,Kanof NB,Kempers SE,Maddin S,Poulin YP,Wilson DC,Hwa J,Liu Y,Graeber M.Adapalene Study Group. Adapalene gel o.3% for the treatment of acne vulgaris: a multicenter,randomized,doubleblind,controlled,phaseⅢ trial[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2):242-50.

[22]Whitney P. Bowe,Amanda K. Doyle,Canice E. Crerand,David J. Margolis,Alan R. Shalita. Body Image Disturbance in Patients with Acne Vulgaris[J].J Clin Aesthet Dermatol,2011,4(7): 35–41.

[23]Spencer E,Ferdowsian H,Barnard N. Diet and acne: a review of the evidence[J].Int J Dermatol, 2009,48,339-347.

[24]Cordain L.Implications for the role of diet in acne[J].Semin Cutan Med Surg, 2005,24(2):84-91.

[25]Pappas A.The relationship of diet and acne: A review[J]. Dermatoendocrinol,2009 Sep;1(5):262-267.

[26]Tuohimaa P,Järvilehto M. Niacin in the prevention of atherosclerosis: signifcance of vasodilatation[J].Med Hypotheses,2010,75(4): 397-400.

[27]Jacobson EL,Kim H,Kim M,Jacobson MK,Niacin: vitamin and antidyslipidemic drug[J]. Subcell Biochem,2012,56:37-47.

Received: 20 May 2016 / Accepted: 15 November 2016

Editor: ZHANG Hui-juan

Contact Information for Corresponding authors∶ Jiang Hao. MD.

Laboratory of Medical Molecular Biology & Clinical Research Department,The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi

University of Chinese Medicine. Dongge Road No.89-9; Nanning city, Guangxi, China. 530023

E-mail∶ Johnjianghao2005@126.com