Migrant Workers in Beijing Feel Pinch of Ride-Hailing Shake-Up

2017-01-10

Winter came early to an urban village on the outskirts of Beijing, whose 5,000 residents have been losing their jobs for months as the city government redefines ride-hailing and the sectors biggest company cuts driver subsidies.

"Look over there — those men are all Didi drivers," said a fruit vendor in Houchangcun village in the northwestern part of Beijing, pointing at a group of men playing poker under a tree during the daytime.

More and more Houchangcun residents, most of whom come from the southwest municipality of Chongqing, have been sitting idle at home in recent months as subsidies gradually dry up and the government tightens regulations on the industry under pressure from state-owned taxi operators.

Nestled in Beijings buzzing Zhongguancun district — an area for a growing class of tech entrepreneurs and venture capitalists — the 15,000-square-meter Houchangcun has become home for migrant workers from Chongqings Pengshui county who left their hometown in the early 1990s in pursuit of a better life.

Most of the migrant workers built a life in the city by working for moving companies. Years of physical work wore down their bodies. Zuo, a 46-year-old driver for Didi who gave only his family name, rolled up one of his trouser legs to show a bulge on his knee, an injury he suffered from carrying heavy loads.

So when ride-hailing superpowers like Uber Technologies Inc. and Didi Chuxing doled out generous subsidies to drivers in the past few years in an effort to secure a slice of the cutthroat industry, Zhu and his fellow villagers saw an opportunity to improve their quality of life. Since the Beijing government has a strict quota on local license plates, they returned to Chongqing, took out loans, bought cars there and drove back to Beijing, joining the tens of millions of ride-hailing drivers in the country.

However, subsidies ebbed after Uber sold its Chinese operations to Didi in exchange for a 20% share in the merged company. Li, another resident of Houchangcun who goes by his family name, saw his revenue drop from more than 10,000 yuan($1,450) a month to about 5,000 yuan. He quit earlier this year.

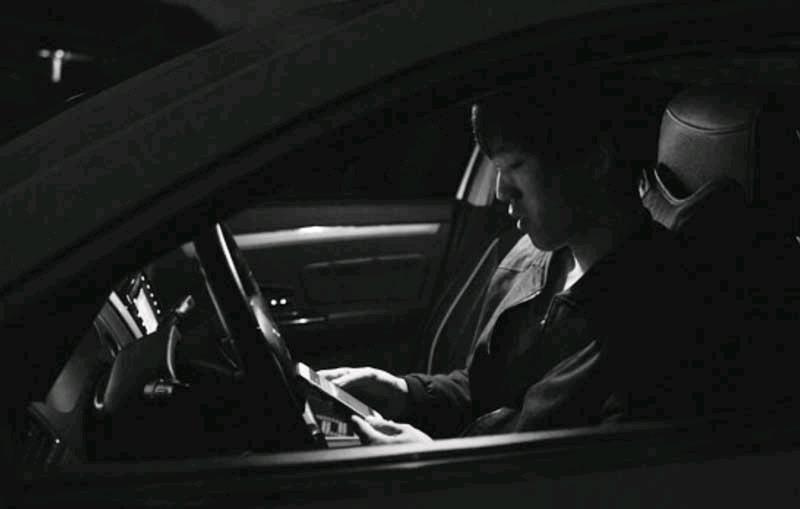

Wang Xudong, a Didi driver in Beijings Houchangcun village, checks orders on his Didi app on Nov.11. Most Didi drivers in Houchangcun start work at night because they cannot drive into downtown Beijing during the day unless their cars hold local licences.

He is not alone. Li said more drivers have quit, especially since local governments decided to limit the pool of drivers in the industry, dealing another blow to Houchangcun.Draft rules issued by scores of cities, including Beijing, in the past month state that only holders of local household registration permits, or hukou, would be able to apply for permits to be drivers for private ridehailing services. Additionally, cars should be registered in the city in which the drivers are working. Some cities also planned to require ridehailing vehicles to have a minimum wheelbase, which would rule out some small compact cars.

Zuo said he understood the requirement for locally registered vehicles if the governments intention is to solve traffic congestion in the city, but prohibiting migrant workers from working in the industry would be "too strict."

"If the government must have a requirement for hukou, how many Beijing natives are willing to drive cars for car-hailing companies?" Zuo asked, adding that migrant workers constitute the majority of drivers.

It is unclear how the ride-hailing companies will cope with the new rules. A manager at a ride-hailing company told Caixin that companies are negotiating with Beijing city authorities for a transitional period. But several other industry insiders said there is little hope of persuading regulators to make major changes to the draft rules. The best that ride-hailing companies can do is try for longer transitions and lenient enforcement.

Li, Zuo and their fellow villagers dont know what the future has in store for them. Compared with other Houchangcun residents, Zuo consid- ers himself lucky because he has only four more months of loans to pay for the cars. But some of his friends just took out loans to buy cars at the beginning of this year to work for the industry. "Now the only way they can pay back is to drive black taxis," Zuo said, referring to unlicensed private taxilike cars that are neither registered nor have insurance.

He considered moving back to Chongqing and continuing driving for Didi, but his hometown seems far away. After living two decades in Beijing, these drivers have perfected their Mandarin and familiarized themselves with every boulevard and alley in the city.

"Im so used to life here now," Zuo said. "There is no hometown that I can go back to anymore."

杂志排行

中国经贸聚焦·英文版的其它文章

- Audi Dealers Jittery Over Parent Company’s Tie-Up With SAIC

- Green Light Turns Yellow for China’s Ride-Hailing Industry

- The Sorrow of Middle Class in China:No Other Choice than Buying Houses

- Wal-Mart is Forming a Closer Relationship with Chinese E-commerce Giant JD.com.

- China Launches Crackdown on an Overheated Property Market

- Alibaba and JD.com Compete Against Supermarkets, Corner Stores