15 Rules of Representation in Media Coverage of Sportswomen:International Trends and Cultural Differences

2016-12-21托尼布鲁斯

托尼·布鲁斯

15 Rules of Representation in Media Coverage of Sportswomen:International Trends and Cultural Differences

托尼·布鲁斯

The thesis is about the 15 Rules of Media Coverageof Sportswomen. Some Rules appear to be disappearing, others are very persistent and some have only become visible with the rise of social media and internet interactivity. Although there are national differences, many of the Rules are found across North America, Australasia, South Africa the United Kingdom and Western Europe, as well as parts of Asia and Eastern Europe.The thesis is to compare the international trends with results from research on Chinese sports media.

Sportswomen; Rules of Representation in Media Coverage; International Trends

0 Introduction

Theoretically,the research emerges from a cultural studies theoretical understanding that the meanings of femininity or masculinity are always in motion. This means that context makes a difference, whether that is historical time period, national context or culture. At the same time, some beliefs about femininity and masculinity have been around for a long time. They have formed what cultural studies scholars call “powerful, immensely strong … ‘lines of tendential force’” (Hall, 1986). Thus, when particular beliefs have “been inserted into particular cultures in a particular way over a long period of time”, they can be highly resistant to change (Hall, 1986).

In cultural studies, we do not generally make claims about whether texts are accurate or inaccurate, truthful or biased. Instead, we take the theoretical position that media stories teach us how tothinkaboutaspects of identity, such as gender. The impact of media coverage is that it slowly transforms our ideas about what are “the most plausible frameworks” we can use to tell ourselves how the world works, and what constitutes reality (Hall, 1984). Therefore, in cultural studies research, wetry to understand how cultural beliefs reveal themselves in the texts (stories, images, videos) produced by media workers and organisations. When we analyse media texts, we view them as “material traces” (McKee, 2003) of plausible frameworks or lines of tangential force. As Alan McKee (2003) argues,”We can never see, nor recover, the actual practice of sense-making. All we have is the evidence that’s left of that practice - the text”. As a result, our focus is the analysis of “how these texts tell their stories, how they represent the world, and how they make sense of it” (McKee, 2003). But this does not mean that all meanings are equally acceptable. Although we cannot argue there is one single accurate or true story about any event - such as a women’s volleyball Olympic final - there are some generally shared understandings. As McKee puts it, “Ways of making sense of the world aren’t completely arbitrary; they don’t change from moment to moment. They’re not infinite; and they’re not completely individual” (2003). Thus, we seek to find out out “whatarethe reasonable sense-making practices of cultures” (McKee, 2003).

In today’s presentation, my focus is a key form of identity - gender - and the way it is culturally, rather than biologically, constructed and interpreted. We know that in organised sport, particularly in the West, women are often seen as Other, while men are understood to be the norm. When an individual or a group (e.g., female athletes) are seen as ‘them’ we are likely to think about and treat them differently (Hall, 1997). And this way of understanding gender has real impacts: on access, on expectations and, unsurprisingly, on media coverage.

To be understood by their audiences, journalists, photographers, and news editors have to work within the practices that already exist. Media producers have had to “learn what are reasonable sense-making practices” in their culture “and think within them” (McKee, 2003). Indeed, their success depends on being able to present information in ways that intersect with the existing frameworks of their readers, listeners or viewers (Desmarais & Bruce, 2008).

1 The Importance of Cultural Context

There is no doubt that the United States dominates research on media representations of sportswomen. As a result, the international research corpus has been strongly influenced by the preoccupations of US researchers, which have focused on genderdifferencesin media coverage rather than gendersimilarities(Bruce, 2015). I recently argued that this focus is an unintended outcome of the early liberal feminist influence on research, which focused on equality with men within existing social structures (Bruce, 2015). Thus, researchers implicitly normalised coverage of men as the desired form of sports media coverage.

The outcome is that cultural differences have not always received the attention they deserve. Indeed, Jinxia Dong (2003) points out that North American and European feminist studies of sport “too often ignore ethnic diversity” and “lack local insight on the diversity of sportswomen’s lives in various parts of the globe”. She argues that Chinese women in sport “have rarely been examined satisfactorily by western sports academics”. Similarly, Ping Wu (2010) identifies the importance of paying attention to cultural and national differences, arguing that in China, “the relationship between elite sport and gender is very different from the Western model”. For example, at every Olympics between 1988 and 2004, Chinese sportswomen won more gold medals than Chinese sportsmen (Wu, 2010).

2 15 Rules of Representation in Media Coverage of Sportswomen

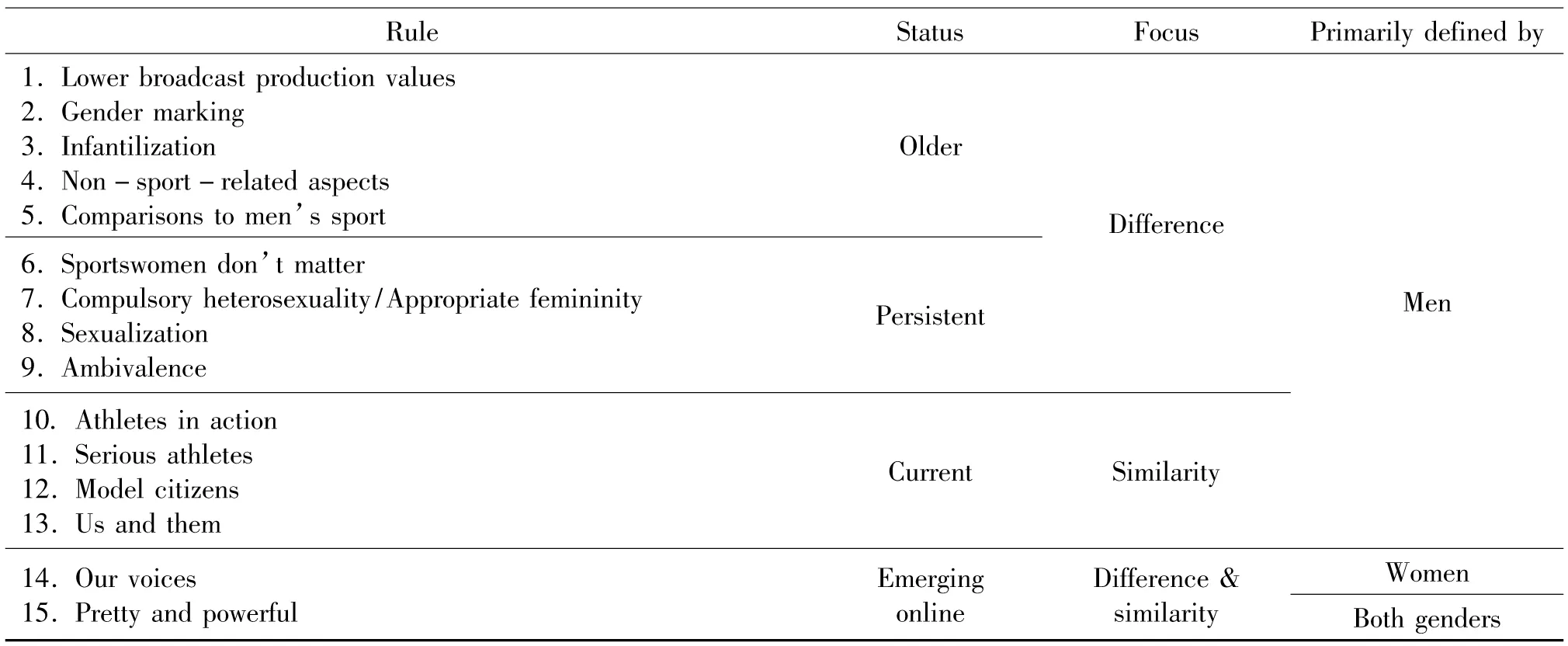

In the next section, I discuss the 15 Rules identified in my review of the existing research (see Table 1), while also paying attention to cultural differences. I separate the Rules into several categories. The first includes 13 Rules that have emerged from studies of mainstream news sources, such as television news or newspapers (print or online). The second includes 2 Rules that seem to be emerging primarily in online, non-news, sites. The first 5 Rules appear to be disappearing, 4have persisted across time, 4 are often ignored in research summaries (especially in the US), and 2 appear to be quite recent. I conclude by discussing one area of representation whose meaning is currently contested by feminist scholars.

Table 1 Media Representation Rules for Sportswomen

2.1 Older Rules

The five older Rules- lower broadcast production values, gender marking, infantilization, non-sport focus and comparisons to men’s sport - were identified during the 1980s and 1990s but seem to be less common today.

LOWER BROADCAST PRODUCTION VALUES

This Rule emerges from research that found television companies invested less time and effort into women’s basketball emerged in United States, and identifiedlower quality in almost all areas of production. However, more recent studies found thatlarge differences in production values were disappearing (Duncan, Messner & Cooky, 2000; Hallmark & Armstrong, 1999).

GENDER MARKING

Gender marking constructs men’s sport as normal and women’s sport as Other, by using a gender modifier only for the women’s event. However, this Rule also appears to be less common today (Bruce, 2015; Jones 2012). In some events, where female athletes are dominant such as netball (Tagg, 2008) or become the focus of national attention such as Cathy Freeman in the 2000 Olympics 400m final (Wensing & Bruce, 2003), it is the men’s events that are gender marked.

INFANTILIZATION

Female power and competence is arguably dismissed in the practice of describing adult sportswomen as girls, young ladies or only by their first names, which was common throughout the twentieth century but is less evident in North America, the United Kingdom and Australia today (Jones, 2012; Tanner, 2011). One recent study found that Spanish media still identify female Olympians as girls or young girls (Crolley & Teso, 2007). Although the media practice of calling sportswomen only by their first names has been interpreted as marginalization, it may also be a sign of respect for their sporting skills.

NON-SPORT-RELATED ASPECTS

This Ruleemerged from studies that found a high level of attention to sportswomen’s lives outside sport - such as family, appearance and personal life - rather than to their sporting performances. Although the gender difference in this form of coverage appears to be reducing (Jones, 2012), except in women’s magazines where it is the standard approach (Pirinen, 1997b), echoes of this non-sport focus can still be found (Billings, Halone & Denham, 2002).

COMPARISONS TO MEN’S SPORT

The practice of positively comparing sportswomen to sportsmen (e.g., the female Yao Ming) may be intended to flatter sportswomen, but researchers argue that it is another way that men’s sport is presented as the standard against which women’s sport should be judged (Poniatowski & Hardin, 2012). Researchers are concerned about the one-way nature of these comparisons - sportsmen are seldom positively compared to sportswomen (e.g., the male Ye Li).

2.2 Persistent Rules

We can think of the next four Rules as the ‘default settings’ that reflect taken-for-granted frameworks for making sense of women in sport. Although these Rules are not absolute nor guaranteed to continue forever, they have established themselves as powerful frameworks that have proven difficult to shift, despite extensive critique.

SPORTSWOMEN DON’T MATTER

The most persistent of all the Rules, the overall invisibility of sportswomen in mainstream sports media represents what Gaye Tuchman (1978) calls symbolic annihilation. Cross-cultural research projects consistently reveal that female athletes gain approximately 10 percent of everyday newspaper coverage (Horky & Nieland, 2013; Jorgensen, 2002, 2005; Lumby, Caple & Greenwood, 2014), although their visibility increases during global events such as the Olympics when they compete in the same stadia as men (Bruce et al., 2010). A recent 20-country comparison, that included Asia, Australasia, Europe, Africa and the Americas (Horky & Nieland, 2013) found that female athletes averaged 11% of coverage. Longitudinal U.S. research on televised sport news found that women have averaged about 5% since 1989 (Cooky, Messner & Hextrum, 2013). The existing Chinese research shows a similar trend, although sportswomen receive slightly more coverage and men slightly less. For example, in two studies since 2000, sportswomen ranged from 16% to 21% where men received 48% to 49% of sports newspaper coverage (see Wu, 2010).However, sportswomen sometimes receive coverage that is is similar in amount to men’s, especially during global events, and some world championships. In China, sportswomen received relatively equal overall coverage to sportsmen (35% to 32%) during the 2004 Olympics, athough this was still disproportionately lower than their proportion on the Chinese Olympic team (66%) or their proportion of gold medals (63%) (Wu, 2010). In another example, a Chinese female gold medalist received less than half the coverage of a male who won gold on the same day.Additionally, some individual sportswomen have become highly visible in social media, although this visibility appears related to first becoming known through mainstream sports media (Bruce, 2015: Bruce & Hardin, 2014).

COMPULSORY HETEROSEXUALITY/APPROPRIATE FEMININITY

I have linked these practices into one Rule because they are so interconnected. This Rule constructs femininity and physical strength as incompatible characteristics that need to be managed through re-presentation that emphasizes heterosexual femininity and hides or negatively represents lesbian identities or “the masculine-looking female body” (Pirinen, 1997b; Knoppers & McDonald, 2010). In China, Wu (2009) argues that since the early 1990s, the feminine traits of female athletes are the most common media focus. Evidence of compulsory heterosexuality appears in research that identified how “Chinese newspapers trivialise female athletes’ skill, performance and achievement by emphasising the contributions made by their male coaches and leaders.

SEXUALIZATION

This Rule, also called sexploitation, focuses on the sexual attractiveness or appeal of sportswomen’s bodies not their athletic ability, and prompts researchers to ask whether the media sees their value as athletes or as sex objects (Australian Sports Commission, 2000; Duncan & Hasbrook, 1988; Pirinen, 1997a; von der Lippe, 2002).From the Chinese context, Wu (2010) reports that research on televised sports news in 2006 found that “trivialisation and sexualisation of female athletes…are alsoovert and blatant in China”. She reported that only female divers (whose bodies fit the petite ideal of “traditional Chinese aesthetics”) were portrayed as “beautiful and sexy” and as “objects for the male gaze” (2009).

AMBIVALENCE

When sportswomen do gain media attention, the difficulties for male sports journalists in balancing discourses of femininity and sport reveal themselves in ambivalent coverage (Scott-Chapman, 2012). The coverage simultaneously focuses on physical skill, achievement and strength valued in sport discourses, and on attributes associated with infantilization, sexualization and compulsory femininity. As a result, the female athlete is represented in contradictory ways that continue to place her outside the ‘norms’ of sport.

2.3 Current Rules

The next four Rules focus on similarities in coverage of sportsmen and sportswomen. Becausethe main research focus has been on difference, these Rules have often received less attention and are seldom included in summaries of the main ways that sportswomen are represented. Much of the research that identifies and explores these current Rules comes from outside the United States.

ATHLETES IN ACTION

Studies of sports photographs have consistently reported few gender differences in how sportswomen are represented, although there remains a large gap in the overall number of images as a result of Rule 6,SportswomenDon’tMatter. These results have primarily been reported in studies of international events in which nations compete against each other and in which the overall number of images of men and women are often similar.

SERIOUS ATHLETES

In all media formats, sportswomen are increasingly being “portrayed as legitimate and serious athletes” (McKay & Dallaire, 2009; Bruce et al., 2010; Caple, 2013; Duncan, Messner & Willms, 2005; Kian, Mondello & Vincent, 2009; Markula, 2009b; Wolter, 2015). However, as I argue elsewhere, “it is not discourses of sport that change to accommodate sportswomen. Instead, sportswomen are represented within existing discourses of sport and masculinity in ways that make gender difference disappear” (Bruce, 2015). As a result,SeriousAthletestories represent men and women in similar ways - as determined, courageous, physically competent sportspeople who are striving for success (Bruce, 2009). This Rule is particularly evident in global events such as the Olympics or world championships, except in the United States where compulsory femininity remained obvious in 2004 (Spencer, 2010), perhaps because newspaper space limitations meant the media had to choose between the many successful, medal-winning U.S. sportswomen (Bruce, 2015).

MODEL CITIZENS

This Rule shares some commonalities with theSeriousAthleteRule in that discourses of femininity or sexualization disappear in the face of discourses of nationalism. Researchers outside the United States report that sportswomen who win on the international stage are frequently represented as successful national citizens and, as Chinese scholar Jinxia Dong (2003) describes it, they “have been frequently and uncritically applauded by the media as national heroes and heroines”. Internationally successful Chinese female athletes have received positive media coverage because of their success for the nation, such as Lang Ping, whose 1995 return to China from the U.S. to coach the Chinese women’s volleyball team “became ‘hot’ media news” with “a live television interview … screeened throughout the country” (Dong, 2003). This pattern may have a long history in China, with Yunxiang Gao (2013) arguing that at the 1936 Olympics, “the female Olympians were the pride of China” . Further, Gao argues for “the critical importance of the healthy, vigorous (jianmei) female body to the development of the nation” (2013). Similarly, Wu (2009) found that modern sportswomen such as diver Guo Jingjing are “not only role models but also fashion icons in Chinese society”. The effect of this Rule has been described in numerous ways in different countrieswhich reported the subordination of discourses of femininity to discourses of nationalism. French colleagues found that “journalistic discourse tends to erase gender with its insistence on national success” (Quin, Wipf & Ohl, 2010). I have argued that “in order for female success to be articulated to nationalism, the more common forms of female representation must be set aside in favour of descriptions that are more usually associated with male athletes”.

US AND THEM

However, there is also evidence that coverage differentiates between sportswomen on the basis of national orgin. In several countries - including Turkey, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand - researchers have revealed a pattern where home-nation athletes are represented asModelCitizensandSeriousAthletesbut sportswomen from other nations are sexualized or feminized (Bruce & Scott-Chapman 2010; Koca & Arslan 2010; Iida 2010). South Korea, for example, held up its own sportswomen as “national icons” but sexualized and marginalized some white sportswomen from Western nations (Koh, 2010).

2.4 Emerging Online Rules

Rules 1-13 have been identified primarily from research that focuses on mainstream media sources, such as newspapers, magazines, television news and live television coverage (whether accessed in print form or online). Evidence for the final two emerging Rules comes primarily from research in online spaces, such as websites and social media sites established by individuals and organisations not directly related to traditional media outlets.

OUR VOICES

The rapid changes in the sports mediascape in the wake of Web 2.0 technologies have turned athletes and sports fans into producers rather than solely consumers of media (Antunovic & Hardin, 2012; Hardin, 2011). Although online and social media sport sites continue to be dominated by men, increasing access to the Internet has created spaces for alternative voices on women’s sport to appear and even gain mainstream media attention (Bruce &Hardin, 2014).

PRETTY AND POWERFUL

The final Rule, which could easily be called Strong and Sexy, is one that may encourage us to rethink theSexualizationRule by challenging the dominant Western belief that, in women, physical strength and power are incompatible with ideals of feminine beauty.However, unlikeOurVoices, evidence of this Rule emerges primarily from US-based websites produced by and/or targeted primarily at men. Marie Hardin and I argued last year that “sportswomen who have risen to prominence in social media are often those who embody both sporting competence and cultural norms of female physical attractiveness” (Bruce & Hardin, 2014). Yet, although some researchers are critical of this form of representation, seeing it as another variation ofSexualization(e.g., Daniels, 2012; Kane et al., 2013; Weaving, 2012), I believe it is important to acknowledge the centrality of sporting competence to these sportswomen’s popularity.

ThePrettyandPowerfulRule values both power and beauty (Bruce, 2015). It can partly be explained by third wave feminism, which argues that “it is a feminist statement to proudly claim things that are feminine …YouwereraisedonBarbieandsoccer?That’scool” (Baumgardner & Richards, 2000, italics in original; see also Cocca, 2014). In addition, third wave feminism also recognizes the complexity inherent in representation, in which images and texts “can bebothempoweringandoppressive” (Beaver, 2014, p. 16, italics in original; Bruce, 2015; Heywood & Dworkin, 2003). Certainly, it has been argued that sportswomen are consciously exploiting the commercial power of their fit and physically strong bodies (Thorpe, 2008; Heywood & Dworkin, 2003). A key element here is sportswomen’s embrace of sporting excellence and femininity as complementary, and the resulting images as empowering: Even though the images are often produced by and for men, the women often have choice or complete control over which ones will be used (Evans, 2004; Heywood & Dworkin, 2003; Stoltz, 2013; Thorpe’s former, 2007).

ThePrettyandPowerfulRule is located at a complex intersection of older and newer understandings of female embodiment generally, and sportswomen specifically. However, female athletes (particularly those who are young, white, heterosexual, toned, and match dominant cultural ideals of beauty) are increasingly seen as representing a body ideal (Heywood & Dworkin, 2003).

Some representations could easily be seen as a form of ambivalence, in which sporting expertise takes second place to forms of sexualization. For example, popular U.S. blog site, The Bleacher Report highlighted tennis player Anna Kournikova, stating “she’s hot and that’s enough for our purposes” (Star, 2010). For another sportswoman, the description read: “In addition to being pretty hot and a tremendously gifted athlete, also seems like a pretty cool person who’s involved in a number of good causes. Plus she tweets tons of great pics. Did I mention she is gorgeous? Oh, right, I did.” In these comments, heterosexiness appears more relevant than sporting expertise. However, in other online representations, the complementary nature of strength and sexiness is much more evident. Thus, it is not whether an image contains nudity or overt sexuality that matters, it is the context in which it appears (Bruce, 2015; Heywood & Dworkin, 2003). Heywood and Dworkin point out that different images “occupydifferent registers informed by different codes”. Thus, images thatcould beinterpretedby some researchers asSexualizationmay instead communicate “power, self-possession, and beauty, not sexual access” (Heywood and Dworkin, 2003).

From a Chinese perspective, it is difficult to assess whether this Rule currently exists or not. However, Yunxiang Gao’s (2013) discussion of how female athletes in the 1930s were worshipped and admired resonates withsome elements of this Rule. She argues that images of “hard, gleaming” sportswomen’s bodies appeared in women’s magazines and their “performances had an uncanny impact on their audiences. Visions of beautiful young women scantily dressed in sports uniforms dazzled male spectators and impressed female fans” . Thus, the revealing female bodies were not only of importance to men but also to Chinese women who embraced “the arrival of the Modern Girl” (Gao, 2013).

3 Conclusion

In conclusion, I suggest that these 15 Rules are only a starting point. We know that research on media representation of women’s sport reveals both shared international trends and some cultural differences, and that dominant forms of representation appear to be in flux, shifting as new frameworks for makingsense of female embodiment emerge in the 21st century. Online and social media appears to be creating spaces for forms of representation that are seldom found in mainstream media coverage. However, because the Rules presented here are based on a sample of existing research published in English, it is likely that other Rules exist and that the dominance of certain rules (e.g.,ModelCitizenversusSexualization) differs in different cultural contexts. It is also possible that, despite more than 30 years of intensive focus on the sports media, researchers have not seen all there is to see. And so I encourage you to explore further, as we continue to try to understand what constitutes the current or historical “reasonable sense-making practices of cultures” (McKee, 2003).

[1] Antunovic, D., & Hardin, M. Activism in women’s sports blogs: Fandom and feminist potential[J]. International Journal of Sport Communication, 2012,5(3), 305-322.

[2] Billings, A. C., Halone, K. K., & Denham, B. E. (2002). “Man, that was a pretty shot”: Ananalysis of gendered broadcast commentary surrounding the 2000 men’s and women’sNCAA Final Four basketball championships. Mass Communication & Society, 5, 295-315.

[3] Bruce, T. Shifting the boundaries: Sportswomen in the media. In A. Henderson (Ed.), Refereed proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Communication Association conference: Communication on the edge 2011[C]. Hamilton,2011.

[4] Bruce, T., & Hardin, M. Reclaiming our voices: Sportswomen and social media. In A. C. Billings & M. Hardin (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Sport and New Media[M]. New York: Routledge,2014: 311-319.

[5] Bruce, T., Hovden, J., & Markula, P. (Eds.). Sportswomen at the Olympics: A Global Comparison of Newspaper Coverage[M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2010.

[6] Bruce, T., & Scott-Chapman, S. New Zealand: Intersections of nationalism and gender inOlympics newspaper coverage. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.),Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage[M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2010: 275-287.

[7] Caple, H. Competing for coverage: Exploring emerging discourses on female athletes in the Australian print media[J]. English Text Construction, 2013,6, 271-294.

[8] Cooky, C., Messner, M. A., & Hextrum, R. H. Women play sport, but not on TV: Alongitudinal study of televised news media[J]. Communication & Sport, 2013,1, 203-230.

[9] Crolley, L., & Teso, E. Gendered narratives in Spain: The representation of femaleathletes in Marca and El Pais[J]. International Review for the Sociology of Sport,2007, 42, 149-166.

[10] Daniels, E. A. Sexy versus strong: What girls and women think of female athletes[J].Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,2012, 33(2), 79-90.

[11] Daniels, E. A., & Wartena, H. Athlete or sex symbol: What boys think of mediarepresentations of female athletes[J]. Sex Roles,2011, 65, 566-579.

[12] Desmarais, F., & Bruce, T. Blurring the boundaries of sports public relations: National stereotypes as sport announcers’ public relations tools[J]. Public Relations Review,2008, 34, 183-191.

[13] Dong, J. Women, sport, and society in modern China: Holding up more than half the sky[M]. London, UK: Frank Cass,2003.

[14] Duncan, M. C., Messner, M. A., & Willms, N. Gender in televised sports: News andhighlights shows, 1989-2004[M]. Los Angeles: Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles, 2005.

[15] Evans, J. Nude photos of Jackson may stir up a storm of controversy[EB/OL].[2004-06-18].Seattle Times online. www.seattletimes.com.

[16] Gao, Y. Sporting gender: Women athletes and celebrity-making during China’s national crisis [M],. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Press,2013.

[17] Hall. S. The spectacle of the ‘Other’’ In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Culturalrepresentation and signifying practices [M]. London: Sage,1997: 223-290.

[18] Hall, S. On postmodernism and articulation: An interview with Stuart Hall[J]. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 1986,10(2), 45-60.

[19] Hall, S. The narrative construction of reality [J]. Southern Review, 1984,17 , 3-17.

[20] Hallmark, J. R., & Armstrong, R. N. Gender equity in televised sports: An analysis ofmen’s and women’s NCAA basketball championship broadcasts [J]. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media,1999, 43, 222-235.

[21] Hardin, M. The power of a fragmented collective: Radical pluralist feminism and technologies of the self in the sports blogosphere. In A.C. Billings (Ed.), Sports media: Transformation, integration, consumption [M]. New York: Routledge, 2011: 40-60.

[22] Hardin, M., Chance, J., Dodd, J. E., & Hardin, B. Olympic photo coverage fair to female athletes [J]. Newspaper Research Journal, 2002,23(2/3), 64-78.

[23] Hartmann-Tews, I., & Ruloffs, B. The 2004 Olympic games in German newspapers -Gender equitable coverage? In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage [M].Rotterdam: Sense Publishers,2010: 115-126.

[24] Horky, T., & Nieland, J-U. Comparing sports reporting from around the world -numbersand facts on sports in daily newspapers. In T. Horky & J-U. Nieland (Eds.), Internationalsports press survey 2011 [M]. Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand GmbH,2013.

[25] Hovden, J., & Hindenes, A. Norway: Gender in Olympic newspaper coverage -towardsstability or change? In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at theOlympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam:Sense Publishers,2010: 47-60.

[26] Iida, T. Japanese case study: The gender difference highlighted in coverage of foreign athletes. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: Aglobal content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers,2010: 225-236.

[27] Jones, D. “Swifter, higher, stronger? Online media representations of gender during the2008 Olympic Games”, in M. K. Harmes, L. Henderson, B. Harmes, & A. Antonio (Eds.), The British world: Religion, memory, culture and society: refereed proceedings of the British World Conference[M]. Toowoomba, Queensland: University of Southern Queensland,2012: 217-233.

[28] Jorgensen, S. S. The world’s best advertising agency: The sports press [J].Mandagmorgen [Mondaymorning], 2005, 37, 1-7.

[29] Jorgensen, S. S. Industry or independence? Survey of the Scandinavian sportspress [J]. Mandagmorgen [Mondaymorning], Special issue, 2002, 11, 1-8.

[30] Kane, M. J., LaVoi, N. M., & Fink, J. S. Exploring elite female athletes’ interpretationsof sport media images: A window into the construction of social identity and “sellingsex” in women’s sports [J]. Communication & Sport, 2013,1, 269-298.

[31] Kian, E. M., Mondello, M., & Vincent, J. ESPN—The women’s sports network? Acontent analysis of Internet coverage of March Madness[J]. Journal of Broadcasting &Electronic Media, 2009,53, 477-495.

[32] Knoppers, A., & McDonald, M. Scholarship on gender and sport in Sex Roles andbeyond [J]. Sex Roles, 2010,63, 311-323.

[33] Koca, C., & Arslan, B. Turkish media coverage of the 2004 Olympics. In T. Bruce, J.Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2010: 197-208.

[34] Koh, E. Media portrayal of Olympic athletes: Korean printed media during the 2004Athens Olympics. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam:Sense Publishers,2010: 237-254.

[35] Lumby, C., Caple, H., & Greenwood, K. Towards a level playing field: sport and genderin Australian media[M]. Canberra, ACT: Australian Sports Commission,2014.

[36] Martin, M. “The big forgotten”: The search for the invisible sportswomen of Spain: Ananalysis of Spanish media coverage during the Olympic Games. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden& P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2010: 127-138.

[37] MacKay S., & Dallaire, C. Campus newspaper coverage of varsity sports: Getting closerto equitable and sports-related representations of female athletes? [M]. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 2009,44, 25-40.

[38] Pedersen, P. M. Examining equity in newspaper photographs: A content analysis of theprint media photographic coverage of interscholastic athletics [J]. International Review for the Sociology of Sport,2002, 37, 303-318.

[39] Pemberton, C., Shields, S., Gilbert, L., Shen, X., & Said, H. A look at print mediacoverage across four Olympiads [J]. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal,2004, 13, 87-99.

[40] Pirinen, R.M. The construction of women’s positions in sport: A textual analysis ofarticles on female athletes in Finnish women’s magazines [J]. Sociology of Sport Journal,1997,14,283-301.

[41] Poniatowski, K., & Hardin, M. “The more things change, the more they …”:Commentary during women's ice hockey at the Olympic Games [J]. Mass Communicationand Society,2012, 15, 622-641.

[42] Quin, G., Wipf, E., & Ohl, F. Media coverage of the Athens Olympic Games by theFrench press: The Olympic Games effect in L’équipe and Le Monde. In T. Bruce, J.Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage[M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2010:103-114.

[43] Redman, K., Webb, L., Liao, J., & Markula, P. Women’s representation in BritishOlympic newspaper coverage 2004. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.),Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers,2010: 73-88.

[44] Scott-Chapman, S. The gendering of sports news: An investigation into the production,content and reception of sports photographs of athletes in New Zealand newspapers[D]. The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2012.

[45] Scott-Chapman, S. South African newspaper sports coverage of the 2004 OlympicGames. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: Aglobal content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers,2010: 257-271.

[46] Spencer, N. E. Content analysis of U.S. women in the 2004 Athens Olympics in U.S.AToday. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage [M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2010: 183-194.

[47] Star, J. The twenty hottest athletes to follow on Twitter[EB/OL].[2010-03-26]. Bleacher Report. http://bleacherreport.com/articles/369208-the-20-hottest-athletes-tofollow-on-twitter

[48] Stolz, G.World champion surfer Stephanie Gilmour’s dad slams ‘sexpolitation’claims of her sexy YouTube ad for Roxy [EB/OL]. [2013-07-14]. The Sunday Mail online.http://www.couriermail.com.au.

[49] Tagg, B. ‘Imagine, a man playing netball!’: Masculinities and sport in New Zealand[J].International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 2008,43, 409-430.

[50] Tanner, W. Marginalization and trivialization of female athletes and women’s sportsthrough commentator discourse: A study of ESPN’s Sports Center[C]. Unpublished Capstone Project. Washington, DC: American University,2011.

[51] Thorpe, H. Foucault, technologies of the self, and the media: Discourses of feminism insnowboarding culture[J]. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 2008,32, 199-229.

[52] Thorpe’s former girlfriend poses for Playboy. Sydney Morning Herald online[EB/OL].[2007-06-08].www.smh.com.au.

[53] Tolvhed, H. Swedish media coverage of Athens 2004. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P.Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage[M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers,2010: 61-71.

[54] Tuchman, G. The symbolic annihilation of women by the mass media. In G. Tuchman,A. Kaplan Daniels, & J. Benet (Eds.), Hearth and home: Images of women in the massmedia[M]. New York: Oxford University Press,1978: 3-38.

[55] Vincent, J., Imwold, C., Johnson, J. T., & Massey, C. D. Newspaper coverage of femaleathletes competing in selected sports in the centennial Olympic games: The more thingschange the more they stay the same[J]. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 2002,12, 1-21.

[56] Weaving, C. Smoke and mirrors: A critique of women Olympians’ nude reflections[J].Sport, Ethics and Philosophy,2012, 6, 232-250.

[57] Wensing, E. H., & Bruce, T. Bending the rules: Media representations of gender duringan international sporting event[J]. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 2003, 38, 387-396.

[58] Wensing, E., & MacNeill, M. Gender differences in Canadian English-languagenewspaper coverage of the 2004 Olympic Games. In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula(Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A global content analysis of newspaper coverage[M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers,2010: 169-182.

[59] Wolter, S. A quantitative analysis of photographs and articles on espn: Positive progress for female athletes[J]. Communication & Sport, 2015, 3(2) 168-195.

[60] Wu, P. China: Has Yin [Female] got the upper hand over Yang [male]? In T. Bruce, J. Hovden & P. Markula (Eds.), Sportswomen at the Olympics: A Global Content Analysis of Newspaper Coverage[M]. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers,2010:211-223.

[61] Wu, P. From ‘iron girl’ to ‘sexy goddess’: An analysis of the Chinese media. In P. Markula (Ed.), Olympic women and the media: International perspectives[M]. New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009: 70-86.

(编辑 潘虹燕)

Toni Bruce, Ph.D, Associate Professor, Pesearch interests: Sport media and management, E-mail:t.bruce@auckland.ac.hz

奥克兰大学教育与社会学院,奥克兰 新西兰 Faculty of Education and Social Work, the University of Auckland, Auckland New Zealand

2015-10-22 Paper presented at Conference on Sport Communication Research in Big Data Era, Chengdu Sport University, October 22-23, 2015.

女运动员在媒体表征中的15条规则:国际趋势与文化差异

Toni Bruce

本文研究了女运动员在媒体中的表征,总结出15条规则,同时研究文化差异在这15条规则中的体现。在这15条规则中,有13条是对传统新闻媒体的研究,如电视新闻或报纸等;有2条是对新媒体的研究,比如网络等。同时,这15条规则中,有5条正在消失,有4条是一直流行至今的,还有4条是最近兴盛起来的,最后2条是随着新媒体的产生流行起来的。这规则具体如下:(1)旧有的正在消失的五条:媒体对女性运动,比如美国的女篮,关注较少;性别标识,男性参与运动是正常的,而女性参与运动则是修饰,是一种调和。比如世界杯,男性参与的世界杯称为世界杯,而女性参与的世界杯称为女子世界杯;对女性运动员的幼稚化描述,对男性运动员更尊重他们的体育能力,而对女性运动员更在意她们的性别,强调年轻女选手或者年轻女孩的一面;媒体更多关注女性运动员的私生活而不关注其运动;在运动中,把男性作为标准,女性以男性为标准进行对比。(2)持续流行的四条:女性运动员不重要;强调女运动员的异性特质或者女性气质;强调女运动员身体的性吸引力,比如,更关注一个女潜水运动员的身材而不是运动技能;在报道女性运动员时,呈现出矛盾。比如性感的画面配上有关运动技能、运动水平的故事。(3)现在流行的四条:体育摄影研究发现,由于规则(女运动员不重要)的原因,女运动员图像的数量比例较低,但在国际赛事或事件中,男女运动员图像的整体数量是相近的;现在媒体常把女运动员描述为认真严肃的运动员,这在奥运会、世锦赛等国际赛事中尤为明显;现在媒体常把为国争光的女运动员描述为模范公民,消除了性别色彩;对本国和别国女运动员报道的不同。对本国女运动员通常报道其认真、模范等特点,而对别国女运动员则多描述性感、女性特质等。(4)新兴的新媒体上的两条:网络社交媒体上,女运动员运用网络社交媒体,但粉丝数量不及男运动员;新媒体上更强调女运动员的力与美的结合,不单看一副画面,而是尽可能了解各个方面。她们可以通过展示自己的身体获得财富,女性的力与美受到了重视。注重塑造赛场上的巾帼英雄与赛后的邻家女孩形象,但这更多针对年轻的白人女性。

女运动员;媒体表征规则;国际趋势

G80-056

A

1001-9154(2016)02-0008-07

G80-056 Document code:A Article ID:1001-9154(2016)02-0008-07