脂肪味是第6种基本味觉吗?

2016-12-14王兴国

王兴国, 高 盼

(江南大学 食品学院, 江苏 无锡 214122)

脂肪味是第6种基本味觉吗?

王兴国, 高 盼

(江南大学 食品学院, 江苏 无锡 214122)

近年来,众多研究报道认为脂肪酸具有基本味觉的特性,提出了第6种基本味觉为脂肪味的观点。综合现有的研究报道结合基本味觉的论证条件,从生物体电生理学特性、心理物理学特性、味觉的主要感受器官、脂肪味与其他基本味觉比较、脂肪味的意义等方面论述了脂肪味作为第六种基本味的论据并不充分。

脂肪味; 脂肪酸; 基本味觉

酸、甜、苦、咸、鲜是目前公认的5种基本味觉[1-2]。2009年,美国普渡大学的Mattes[3]教授论述了脂肪酸具有基本味觉的特性——脂肪味,可能是第六种基本味觉,这引起了国内外学者的广泛关注,美国、日本等国进行了大量的细胞、动物实验和感官及调研实验来论证脂肪味存在及其意义,并发表了大量的学术研究和多篇高影响因子的综述[4]。

1997年在圣地亚哥举行的鲜味大会上明确提出了基本味觉的条件[5]:1)在食物中普遍存在;2)满足电生理学和心理物理学的要求;3)存在独特的感觉器官;4)不是其他基本味觉混合而成。除此之外,基本味觉也必须存在其特殊的意义。那么,脂肪味能否被称为第六种基本味道?本文将综合公开发表的文献资料,结合基本味需满足的条件以及其他基本味认证方式,论述脂肪味作为第六种基本味的论据是否充分。

1 食物中普遍存在方面

普遍认为脂肪味的呈味物质是游离脂肪酸[6],而不是甘油三酯。这些游离脂肪酸来源于食物[7-12]和/或舌脂酶分解甘油三酯产生[13-15]。在啮齿动物中,加入舌脂酶抑制剂,抑制甘油三酯水解,小鼠对脂肪的偏好降低[16],这也侧面证明脂肪味的呈味物质是游离脂肪酸而不是甘油三酯。Fushiki[17]通过大鼠口服脂肪假饲实验,发现油酸、亚油酸和亚麻酸能引起脂肪化学接收机制的胰腺酶的短暂升高,而辛酸、短碳链脂肪酸不能引起该反应,证明中短碳链脂肪酸不是脂肪味的呈味物质。

味觉受体反应决定了脂肪味的具体呈味物质。在外向延迟整流钾离子通道(delayed rectifying potassium channels,DRKs)通路中只有顺式长碳链不饱和脂肪酸能引起通道的反应[14]。分化簇36(cluster of differentiation 36,CD36)也只与长碳链脂肪酸发生可逆的特异性结合[18-19],而中碳链和短碳链脂肪酸不与CD36结合。中长碳链脂肪酸能有效刺激味觉受体,碳链长度14-18的饱和脂肪酸(SFA)和碳链长16-22的不饱和脂肪酸是G蛋白偶联受体120(G protein receptor 120,GPR120)的配体[3, 20],该受体不结合碳链长度小于12的游离脂肪酸[20-21]。

脂肪酸的呈味物质研究还是比较完善的,即碳链长度14~18个碳的饱和脂肪酸和16~22个碳的顺式不饱和脂肪酸是基本呈味物质。

2 电生理学特性方面

电生理学是以作用于生物体的电作用和生物体所发生的电现象为主要研究对象的生理学的一个分支领域[22]。在味觉研究中,常用动作电位来研究神经系统的机能。电压门控离子通道作为味觉细胞兴奋性的分子基础,在味觉信息的前期编码和处理中具有重要意义。味觉信息经过输入神经,包括面神经鼓索支、舌咽神经和迷走神经,进入脑干,经丘脑,最后到达大脑皮层进行味觉感知[23]。

5种基本味觉的传导机制已经研究很多。苦、甜、鲜味是这3种味觉感受味质与相应的味觉受体(GPCR)结合产生,甜味、苦味和鲜味的味觉传导途径见图1。由图1可知,从而激活味觉特异性G蛋白α-味导素(α-gustducin),导致G蛋白β和γ亚基的分离,激活磷酸酶β2(PLC-β2)产生肌醇三磷酸(IP3),IP3与第三类肌醇三磷酸受体(IP3R3)结合,导致胞内细胞器膜上IP3-门控钙离子通道的开放,胞内储存的钙离子被释放出来,引起胞质内钙离子浓度上升,进而引起瞬时电位M亚型5(TRM5)通道开放,钠离子流入细胞内,最终导致膜去极化和神经递质释放[24-26]。

图1 甜味、苦味和鲜味的味觉传导途径Fig.1 Taste pathway of sweet, bitter, and umami

酸味信号转导可能涉及3种机制:1)通过阿米洛利敏感性钠离子通道的质子渗透来传导酸味;2)细胞内外因素固定式封闭电导;3)质子门控通道。至今并没有明确的关于酸味信号转导通路方面的报道。动物中的咸味反应可能涉及很多信号转导机制,而这些信号转导机制可能与阿米洛利敏感性成分或阿米洛利不敏感性成分有关。至今,并没有关于咸味受体分子进化机制方面的报道[27]。

脂肪味的传导机制类似于苦、甜、鲜,都发生在Ⅱ型细胞中。从口腔中摄入的脂肪酸先进入细胞内,细胞外的脂肪酸进入细胞主要方式有2种:1)靠浓度差,脂肪酸先溶于细胞膜,再从外膜翻转到内膜,此效率较差。2)细胞膜上蛋白质帮助运送,脂肪酸运送蛋白(FATP)与长碳链脂肪酸的酰基辅酶A合成酶联结在一起,防止脂肪酸再跑出细胞膜外,同时减少膜内脂肪酸的浓度,形成浓度差而加速运入细胞。因此,虽然脂肪味的呈味物质是脂肪酸,但与酸味的呈味物质(乙酸等短碳链脂肪酸)不重合,且酸味发生在Ⅲ型细胞中,目前没有研究表明脂肪味的作用机制与Ⅲ型细胞有关,因此认为脂肪味并不是酸味。

目前认为脂肪酸的传导方式有两种,一种是外向延迟整流钾离子通道,另一种是钙离子通道。舌前味觉细胞中,shaker kv1.5(KCNA5)通道激活打开,胞内钾离子向外流动形成外向电流,多不饱和脂肪酸与CD36结合,使CD36发生C型失活,C型失活激活快,失活慢。从而导致kv1.5离子通道关闭,抑制钾离子外流,引起膜去极化和神经递质的释放[28-29]。但在甜味和酸味的研究中[30-31],通过两栖类动物和仓鼠进行实验发现也降低了钾离子电流和引起味觉细胞去极化。因此,外向延迟整流钾离子通道反应可能不是脂肪酸独特的机制,但可能代表了一种更普遍的参与味觉反应的下游机制。同时物种之间的潜在差异,会对实验结果造成一定影响。

钙离子通道是更为普遍的传导方式。脂肪酸和CD36/GPR120结合,激活磷酸酶β2产生肌醇三磷酸,肌醇三磷酸与第三类肌醇三磷酸受体结合,导致胞内细胞器膜上肌醇三磷酸- 门控钙离子通道的开放,胞内储存的钙离子被释放出来,引起胞质内钙离子浓度上升,进而引起瞬时电位M亚型5通道开放,钠离子流入细胞内,最终导致膜去极化和神经递质释放[32]。

Tepper等[33]报道了2种基因可能在人类对脂肪的感知和偏好中发挥作用,分别是tas2r38和CD36。tas2r38是苦硫脲味觉受体,包括6-n-丙基硫氧嘧啶(PROP)和苯硫脲(PTC),与品尝苦味硫脲化合物PROP的能力高度相关。

脂肪味的表达与苦味表达基因有关,那么是否表示脂肪味和苦味有关联,甚至脂肪味是苦味和其他味觉的混合味呢?目前还没有其他的研究对这一观点进行解释。若脂肪味的表达与苦味的表达基因相关,那么脂肪味可能就不是一种单一味觉更不是基本味觉。

3 心理物理学特性方面

心理物理学是指对物理刺激和它引起的感觉进行数量化研究的心理学领域[34]。多强的刺激才能引起感觉,即绝对感觉阈限的测量;物理刺激有多大变化才能被觉察到,即差别感觉阈限的测量;感觉怎样随物理刺激的大小而变化,即阈上感觉的测量。

Tucker等[35]总结前人的研究,认为油酸的阈值范围约0.02~12 mmol/L[36-39];Newman等[40]亚通过感官评价将油酸的察觉阈值精确为0.26 mmol/L,油酸的阈值范围是0.04~4.7 mmol/L。但Ozdener等[41]进行人体味觉细胞实验发现,5 μmol/L的亚油酸就能引起细胞电位的变化,因此认为人的察觉阈浓度应为5 μmol/L,同时,Stewart等[42]研究表明人类的油酸和亚油酸的阈值变化超过2至4个数量级,差别阈值也恒定在0.5 mmol/L左右[43-44]。

Kawai等[45]对舌脂酶进行了详细的描述,舌脂酶由味腺(von Ebner’s gland)分泌,它是哺乳动物消化和吸收脂肪的一种辅助酶,其在口腔中分解脂肪的机制目前并不清楚。Hamosh等[46]和Primeaux等[47]认为,舌脂酶在口腔中分解膳食中的甘油三酯,将其部分分解成甘油单酯和甘油二酯以及游离脂肪酸,并通过味腺将这些亲脂性分子运输到口腔溶液环境中,细胞对长碳链脂肪酸形成的脂肪进行识别[48-49]。舌脂酶对啮齿动物的作用明显,实验证明[50-51]啮齿动物加入脂肪酶抑制剂会影响甘油三酯的偏好,而不影响脂肪酸的偏好,表明舌脂酶在口腔中作用于甘油三酯。但舌脂酶对人的作用却存在争议,在婴幼儿口腔中,舌脂酶存在且具有重要作用[52],但在成人口腔中舌脂酶活力很低[43]。因此,舌脂酶是否能作用于成人,使膳食中的甘油三酯分解成游离脂肪酸还需进行进一步的论证。

若舌脂酶不存在,那么仅从食物中获取的游离脂肪酸能否达到察觉阈值的浓度呢?以大豆油为例,根据国标GB 1535—2003,一级大豆油酸价为0.2,按油酸比例计算,1克油的油酸含量约为7.15 μmol/L,但精炼更好的大豆油酸价可以降低一个数量级,在这种情况下,摄食的油酸浓度是否能达到脂肪味阈值的下限还未可知。同时目前所有的动物实验或感官实验都用纯的脂肪酸作为样品,在摄食过程中,咀嚼时间、进食频率和游离脂肪酸的吸收率等都会对口腔中游离脂肪酸的量产生影响,无法确定能否达到脂肪味的感知阈。因此,对于心理物理学特性的研究也不完善。

4 特定感觉器官方面

味觉的主要感受器官是味蕾[53]。在哺乳动物中,它主要分布在舌[2]、上颚和咽部黏膜处[54]。舌是由横纹肌束交织而成,其背面分布着四种不同类型的舌乳头:丝状乳头、菌状乳头(FF)、叶状乳头(FL)和轮廓乳头(CV),其中菌状乳头、叶状乳头和轮廓乳头因含有味蕾而被称为味乳头。食物的味觉信号是由味觉细胞定位于化学感受器官[55],几种脂味受体细胞[56-60],特别是游离脂肪酸受体存在于人的味蕾[59, 61-62]。

哺乳动物的味蕾顶端在口腔的上皮表面开口为味孔,味孔是味蕾成熟的形态学标志。味蕾由50~150个味蕾细胞组成,这些细胞根据细胞形态可分为四种类型,分别定义为I型细胞(暗细胞)、Ⅱ型细胞(亮细胞)、Ⅲ型细胞(中间细胞)和Ⅳ型细胞(基细胞)。Ⅰ型细胞像神经胶质细胞一样在味蕾其他类型细胞的周围,具有清除递质和隔离其他类型细胞的作用[63];Ⅱ型细胞主要表达味觉GPCR,PLCβ2,IP3R3和TRPM5等甜、苦和鲜味转导所需的功能因子,因此认为该型细胞是味觉感受细胞,也是味觉信号转导的基础[64];Ⅲ型细胞表达突触小体相关蛋白质和神经细胞黏附分子,其同味觉信号传递到神经系统的过程有关;Ⅳ型细胞位于味蕾的基底部分,是圆形的增殖干细胞,由该型细胞分化产生其他各种味觉细胞。

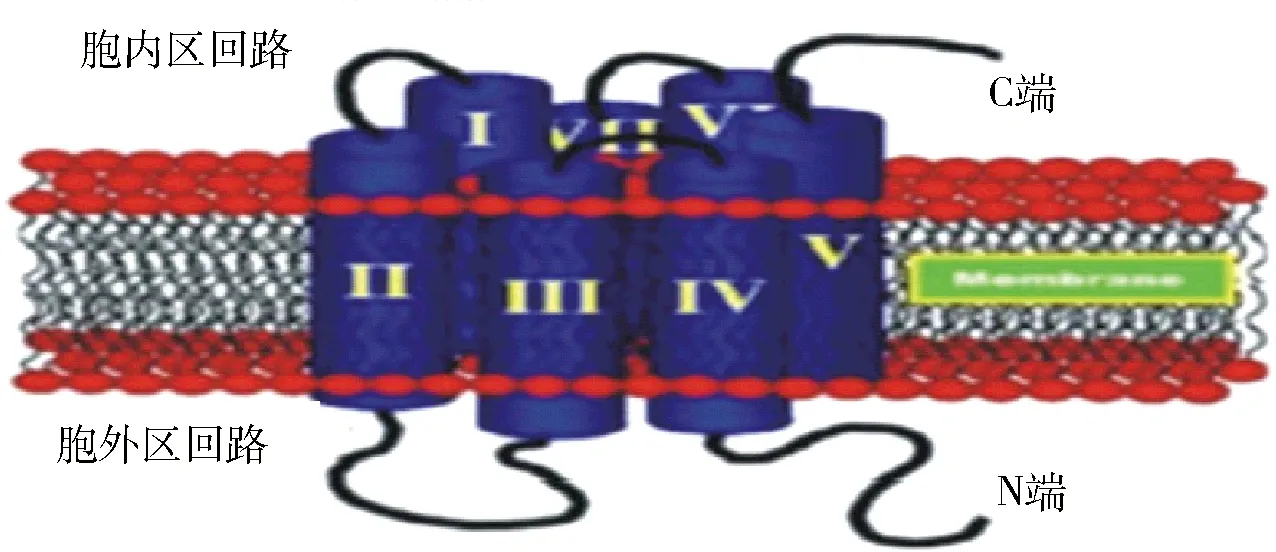

CD36是一种多功能蛋白的B类清道夫受体SR-B1[65],如图2,主要存在于持续的脂质代谢组织和一些造血干细胞中。CD36参与多种生理和病理过程中血管形成[66]、血栓形成[67]、动脉粥样硬化、阿尔茨海默症[68]和疟疾。CD36另一个重要的功能是作为脂质传感器[69],它是一种脂肪酸转移酶(fatty acid translocase,FAT),研究表明与外部环境(味觉、肠道或嗅觉上皮细胞)相连的CD36能与膳食脂肪的外源性衍生配体相结合,在啮齿动物下丘脑腹内侧核神经元中,CD36也能感知到脂肪酸[70]。CD36蛋白为多肽单链,包括两个跨膜区域,其羧基末端(C端)和氨基末端(N端)各有一个连续的疏水氨基酸区,两个疏水末端作为与细胞膜结合的支柱被固定在细胞膜上,使其长链大部分延伸在胞外。它的膜外周区有多个N-连接的糖苷化位点,这些结合位点主要结合抗血管生成蛋白凝血酶敏感蛋白-1 (thrombospondin-1,TSP-1)[71],氧化低密度脂蛋白和凋亡细胞[71-72],以及长碳链脂肪酸[69],C-末端可能参与受体激酶调节的信息传导作用[73]。

图2 CD36的结构图Fig.2 Structure of CD36

CD36的表达参与脂肪酸转运过程,与表达于整个味细胞细胞质内的α-味导素相比,CD36的表达明显局限于味蕾细胞的顶端[56],并且位于味孔的内侧。这是已知的对长碳链脂肪酸有高度亲和力的蛋白质的位置,特别适合于接受来自饮食中脂类物质的刺激。CD36的C-末端与激酶相连,这与细胞内信号转导相关[74]。CD36主要存在于轮廓乳头[58, 75],少量存在于叶状乳头中,几乎不存在于菌状乳头,用于提高其对膳食脂肪察觉的敏感性。

关于CD36作为脂肪受体的研究很多,Sclafani等[57]对比敲除CD36基因的小鼠和野生型小鼠,发现敲除CD36基因的小鼠对大豆油和亚油酸的偏好消失;Chen等[76]通过干扰RNA抑制舌上CD36的表达,结果发现对亚油酸的偏好也降低。Zhang等[77]证明饮食诱导肥胖的大鼠轮廓乳头味蕾中CD36的表达低于正常体重控制饮食的大鼠,因为表达水平下降,导致对脂肪的敏感性更低,以至于摄入的脂肪更多。Chevrot等[78]则认为,正常小数和肥胖小鼠轮廓乳头中CD36餐后短时表达无差异但饭后1小时正常小鼠CD36表达下降。类似的研究[79]表明小鼠轮廓乳头的CD36表达与口腔脂肪暴露直接相关,在舌表面直接附着油脂,CD36的表达下降。胰高血糖素样蛋白1(GLP-1)也是CD36的表达信号[80],GLP-1基因敲除小鼠也不显示轮廓乳头的CD36餐后表达下调。缺乏CD36的人空腹和餐后的游离脂肪酸和甘油三酯水平较高,也更易出现胰岛素抵抗,甚至没有多余的脂肪积累[81]。体重正常与超重/肥胖的人相比较,口腔中游离脂肪酸敏感性测试表达了CD36变化的潜在机制[38, 43, 82],游离脂肪酸阈值测试存在个体差异[83],人类CD36的表达和游离脂肪酸敏感度之间的假设关系,还需要进一步研究。

GPCR中文名称是G蛋白偶联受体,其结构如图3。在各类受体中,GPCR是成员最多的一大类,目前已知的GPCR有1000多种[84]。尽管GPCR所介导的信号转导通路极为复杂,但在结构上它们均由单一的多肽链构成,形成7次跨膜结构。G蛋白是GPCR与胞内信号通路偶联的关键分子,它是由α、β和γ亚基组成的三聚体。其中α亚基是G蛋白主要的功能性亚基,β和γ亚基通常形成功能性的复合体,它们在GPCR信号转导中都起到重要作用。GPCR的各跨膜区段之间由亲水的细胞内外的肽环相连接,在细胞膜外的N末端有糖基化位点,而胞内C末端有丝氨酸和苏氨酸的磷酸化位点[85-86]。受体的N端或跨膜区可形成配体结合域,连接跨膜区段的胞内环以及C端则形成G蛋白结合域。GPCR对各种组织中的脂肪酸具有选择性[87],GPCR与脂类等小分子配体的受体结合位点主要位于由7个跨膜区段所构成的跨膜螺旋区段的中心,它使配体分子或多或少的平行于质膜表面。

图3 GPCR的结构图Fig.3 Structure of GPCR

GPCR通过G蛋白可以间接或直接的途径对离子通道进行调节。间接途径是指当GPCR激活时,G蛋白随之激活效应器,再通过第二信使系统下游通路如蛋白激酶对离子通道进行磷酸化调节,或者是第二信使直接门控一些离子通道。这是GPCR对离子通道调节的最主要方式。另外,第二信使如IP3等可直接激活IP3R3、环核苷酸门控离子通道HCN和CNC等。除间接的调节外,G蛋白还可以直接调节离子通道活性。一方面,G蛋白的α亚基或βγ复合体本身可以门控离子通道,另一方面G蛋白的α亚基或βγ复合体也可以调节离子通道的活性。

在味觉上皮细胞中,存在两种引起广泛研究的GPCR,分别是GPR120和GPR40。这两种蛋白都在啮齿动物的味觉细胞中出现,但不同于GPR120,GPR40在人的味觉组织中几乎不存在[62, 88]。GPR120属于进化保守的视紫红质家族受体[89],目前的研究表明,饱和与不饱和的长碳链脂肪酸通过激活GPR120受体参与调节一系列的代谢过程。GPR120与5-HT2受体偶联,激活磷酸酶,长碳链脂肪酸与GPR120受体结合引发下游一系列的反应[20, 90]。

GPR120存在于人类和啮齿类动物的菌状乳头、轮廓乳头和啮齿类动物的叶状乳头中[62];人类的叶状乳头没有检测到GPR120基因的存在。GPR120和GPR40都是ω-3脂肪酸受体[20, 62, 91-94]。Godinot等[95]研究证明在啮齿动物中,GPR40介导的味觉感受不足以产生偏好。Sun等[96]通过计算机模型设计研究发现GPR120的羧基端对GPR120和脂肪酸的结合起重要作用。GPR120基因敲除的小鼠对油酸和亚油酸的偏好降低[59],但是对大豆油乳剂的喜好不变[97]。

脂肪味的传导机制是大部分专家学者的主要研究方向,大部分都认同外向延迟整流钾离子通道和钙离子通道两条传导途径,这两条途径都跟味觉接收受体CD36有关,但相关的传导效率和关联性没有过多的阐述和报道,因此该部分还具有深入探索的必要。实验证明[78]CD36和GPR120两种受体的作用并不相同,CD36对脂肪酸的亲和力大于GPR120[98]。根据目前的研究,提出了CD36和GPR120作用的假设[41]:对长碳链脂肪酸亲和力高的CD36是脂肪味觉感知的第一受体,在低浓度时只有CD36运载脂肪酸并产生作用,GPR120能扩大脂肪酸的信号,在长碳链脂肪酸浓度较高时GPR120能控制CD36作用剩余的脂肪酸扩大离子信号,加强了化学信号到电信号的转换,增强了感知的阈值强度,但该假设没有得到证实。

脂肪味传导有关的味觉神经主要是双侧鼓索神经和舌咽神经[3]。鼓索神经并入三叉神经的分支舌神经中并随其分布,味觉神经纤维主要分布到舌前2/3,舌咽神经经分布于舌后1/3的味蕾。通过一系列实验[16, 99-100]证明切断鼓索神经和舌咽神经,脂肪的摄入量和偏好减少,从而证明这两种神经对脂肪味的重要作用。Stratford等[99]切断大鼠双侧鼓索神经,发现母鼠对亚油酸感知阈值上升一倍,公鼠阈值上升七成。Gaillard等[16]切断大鼠舌咽神经,发现大鼠在30min和48h的双瓶实验中对2%亚油酸的偏好产生影响,同时全部切除这两种神经,小鼠对亚油酸的偏好消失。

感觉器官是脂肪味研究中最完善的部分,但仍然存在许多未解之处,比如CD36和GPR120之间的关系,传导效率等问题都没有相关报道,脂肪味是否涉及其他的感觉器官也未可知。

5 与其他基本味觉比较

Mattes[101]研究发现在受试者夹鼻检测时,亚油酸使咸味和苦味的阈值强度降低,对氯化钠、蔗糖阈值无显著影响,柠檬酸,咖啡因阈值显著增高。虽然这项研究并没有排除脂肪酸可能对其他味道化合物灵敏度有调节作用,但证明了脂肪酸对基本味觉具有影响,其作用机制有待研究。Gilbertson等[102]给S5B大鼠喂食0.5mmol/L的糖精和5~20μmol/L的亚油酸混合物,与单独喂食相同浓度的糖精和亚油酸。通过行为学观察发现,大鼠对添加亚油酸和糖精的偏好明显高于分别喂食单一物质,因此认为在一定浓度内亚油酸和糖精具有协同效应。Pittman等[100]进一步研究发现,在蔗糖和葡萄糖中加入88μmol/L的亚油酸、油酸或两者的混合会增强Osborne-Mendel大鼠在20s内的舔舐率。Ninomiya[103]证明脂肪酸对苦味的响应会影响小鼠的神经反应。Tepper[33]也证明对苦味不敏感者,对甜味和脂肪的偏好阈值更高。

在鲜味论证过程中[5],利用多维尺度分析(multidimensional scaling analysis, MDS)证明鲜味与其他基本味觉不混合,目前没有把多维尺度分析运用到脂肪味研究的文献报道。脂肪味的感官实验都是小样本量的感官分析,导致实验结果局限,可靠性存疑。现有的文献资料只能证明脂肪味的呈味物质可能对其他基本味觉产生影响,但不足以论证脂肪味和其他基本味觉不重合,是一种独立的其他味觉。

6 脂肪味的意义

哺乳动物显示出明显的喜好脂肪丰富的食物[104-105],不良的饮食习惯是导致肥胖的重要因素[106-108],脂肪味与肥胖具有极大的关联。游离脂肪酸具有细胞毒素,因此推测脂肪味可以根据其游离脂肪酸含量帮助提醒人类避免潜在的有毒物质[109]。口腔脂肪暴露可能阻止人们摄入腐臭的食物同时提高胃肠的脂类加工和消化[56, 110-111]。

Mattes[112]认为口腔暴露全脂食物比无脂食物有较高的餐后血脂,而后又进一步论证这种变化不能通过触觉和嗅觉进行解释,因此认为引起这种变化的原因是味觉感知[113]。Tucker等[83]进行观察48名成年受试者,发现饱和脂肪摄入量和感知阈值正相关(摄入量越大,阈值越高),而肥胖者对脂肪酸灵敏度低。Haryono等[114]的研究已经表明,口腔中脂肪酸的敏感度,特别是油酸的识别与BMI、膳食脂肪的消耗量和食物中脂肪识别能力有关。Asano等[115]通过25名成年人的自我报告问卷调查得出结论:油酸阈值不仅与BMI有关,与高脂甜食的偏好和饮食习惯也正相关。Newman等[116]进行一份553人持续6周的随机饮食干预实验,证明持续低脂饮食和部分控制脂肪饮食都能增强超重/肥胖的人群对脂肪的感知强度,其中低脂饮食效果更为明显,同时短期改变饮食习惯并不能改变其脂肪偏好。

正是因为脂肪味的存在可能与肥胖相关,才引起食品、营养学及医学方面学者的广泛关注,他们认为如果论证了脂肪味的存在,对于研发脂肪替代物具有极其重要的指导意义。

综上所述,脂肪味的呈味物质和感觉器官理论研究较为完善,但实验论证过程集中在亚油酸和油酸,对其他脂肪酸几乎没有涉及;虽然论证了CD36和GPR120的作用,但其关联性没有实验论证;同时并没有直接的论据表明脂肪味不与其他基本味觉混合;其电生理学和心理物理学研究也并不完善,现有的资料和报告论证并不充分,现在下结论脂肪味是基本味觉为时尚早。

自2009年Mattes教授提出脂肪味的观点以来,在论证脂肪味存在及其是基本味觉的过程中,人们不断地通过基本味觉的4大条件来进行论证,但理论依据尚有不足,存在很多值得深入研究和反复推敲的地方,所以脂肪味是第六种基本味觉这一观点尚不能下定论。鲜味的基本味觉论证从提出到被广泛认同经历了近80年的时间,甚至到现在都有部分国家和地区不认为鲜味是基本味觉,因此可以推测脂肪味的研究和论证还将经过漫长的道路。

[1] NINOMIYA K. What is umami?[J]. Food Reviews International, 1998, 14(2):123-138.

[2] BRESLIN P A, SPECTOR A C. Mammalian taste perception[J]. Current Biology, 2008, 18(4):148-155.

[3] MATTES R D. Is there a fatty acid taste?[J]. Annual Review of Nutrition, 2009, 29(1):305-327.

[4] 侯威. 脂肪味会成为第六种滋味么?[J]. 中国食品学报, 2015,15(7):239-240.

[5] KURIHARA K. Umami the fifth basic taste:history of studies on receptor mechanisms and role as a food flavor[J]. Biomed Research International, 2015: 189-202.

[6] TUCKER R M, MATTES R D, RUNNING C A. Mechanisms and effects of “fat taste” in humans.[J]. Biofactors, 2014, 40(3):313-326.

[7] MATTES R D. Fat taste in humans: is it a primary?[M]∥MONTMAYEUR J P, LE COUTRE J. Fat detection: taste, texture, and post ingestive effects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2010.

[8] SMITH J C. Orosensory factors in fat detection[M]∥MONTMAYEUR J P, LE COUTRE J. Fat detection: taste, texture, and post ingestive effects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2010.

[9] STRATFORD J M,CONTRERAS R J. Peripheral gustatory processing of free fatty acids[M]∥MONTMAYEUR J P, LE COUTRE J. Fat detection: taste, texture, and post ingestive effects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2010: 833.

[10] GILBERTSON T A, YU T, SHAH B P. Gustatory mechanisms for fat detection[M]∥MONTMAYEUR J P, LE COUTRE J. Fat detection: taste, texture, and post ingestive effects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2010.

[11] ACKROFF K, SCLAFANI A. Oral and postoral determinants of dietary fat appetite[M]∥MONTMAYEUR J P, LE COUTRE J. Fat detection: taste, texture, and post ingestive effects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2010.

[12] PITTMANW D. Role of the gustatory system in fatty acid detection in rats[M]∥MONTMAYEUR J P, LE COUTRE J. Fat detection: taste, texture, and post ingestive effects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2010.

[13] GILBERTSON T A,LIU L,KIM I,et al. Fatty acid responses in taste cells from obesity-prone and -resistant rats[J]. Physiology and Behavior, 2005, 86(5): 681-690.

[14] GILBERTSON T A,FONTENOT D T,LIU L,et al. Fatty acid modulation of K+ channels in taste receptor cells: gustatory cues for dietary fat[J]. The American Journal of Physiology, 1997, 272(4):1203-1210.

[15] SMITH L M,CLIFFORD A J,HAMBLIN C L,et al. Changes in physical and chemical properties of shortenings used for commercial deep-fat frying[J]. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 1986, 63(8): 1017-1023.

[16] GAILLARD D,LAUGERETTE F,DARCEL N,et al. The gustatory pathway is involved in CD36-mediated orosensory perception of long-chain fatty acids in the mouse[J]. FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2008, 22(5): 1458-1468.

[17] FUSHIKI T. Why fat is so preferable: from oral fat detection to inducing reward in the brain[J]. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 2014, 78(3): 363-369.

[18] BAILLIE A G S,COBURN CT,ABUMRAD N A. Reversible binding of long-chain fatty acids to purified FAT:the adipose CD36 homolog[J]. Journal of Membrane Biology, 1996, 153(1): 75-81.

[19] IBRAHIMI A,SFEIR Z,MAGHARAIE H,et al. Expression of the CD36 homolog (FAT) in fibroblast cells: effects on fatty acid transport[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1996, 93(7): 2646-2651.

[20] HIRASAWA A,TSUMAYA K,AWAJI T,et al. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120[J]. Nature Medicine, 2005, 11(1): 90-94.

[21] DAMAK S, LE-COUTRE J, BEZENCON C, et al. Fat taste receptors and their methods of use: EP2006/064043[P].2007-08-02.

[22] 金文泉.可兴奋细胞的生物电现象[J]. 中国医师进修杂志, 1982(8):19-22.

[23] 陈培华. 味觉细胞模型及仿生味觉细胞网络传感器的研究[D].杭州:浙江大学,2010.

[24] MARGOLSKEE R F. Molecular mechanisms of bitter and sweet taste transduction[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2002, 277(1): 1-4.

[25] KINNAMON S C. Umami taste transduction mechanisms[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2009, 90(3): 753S-755S.

[26] 陈大志,叶春,李萍. 味觉受体分子机制[J].生命的化学, 2010, 5(30): 810-814.

[27] MIYAMOTO T, FUJIYAMA R,OKADA Y,et al. Acid and salt responses in mouse taste cells[J]. Progress in Neurobiology, 2000, 62(2): 135-157.

[28] GUTMAN G A. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels:potassium channels[J]. Pharmacological Reviews, 2004, 55(4): 583-586.

[29] LIU L,HANSEN D R,KIM I,et al. Expression and characterization of delayed rectifying K+channels in anterior rat taste buds[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 2005, 289(4): C868-C880.

[30] KINNAMON S C,BEAM K G. Apical localization of K+channels in taste cells provides the basis for sour taste transduction[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1988, 85(18): 7023-7027.

[31] CUMMINGS T A,KINNAMON S C. Sweet taste transduction in hamster:sweeteners and cyclic nucleotides depolarize taste cells by reducing a K+current[J]. Journal of Neurophysiology, 1996, 75(75): 1256-1263.

[32] CLAPP T R,MEDLER K F,DAMAK S,et al. Mouse taste cells with G protein-coupled taste receptors lack voltage-gated calcium channels and SNAP-25[J]. BMC Biology, 2006, 4(1): 7.

[33] TEPPER B J. The taste for fat: new discoveries on the role of fat in sensory perception, metabolism, sensory pleasure, and beyond[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2012, 77(3):6-7.

[34] 杨治良.心理物理学[M].兰州: 甘肃人民出版社,1988.

[35] TUCKER R M, MATTES R D. Are free fatty acids effective taste stimuli in humans ?[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2012, 77(3):148-151.

[36] CHALÉRUSH A R,BURGESS J R, MATTES R D. Multiple routes of chemosensitivity to free fatty acids in humans[J]. American Journal of Physiology GastrointestinalandLiver Physiology, 2007, 292(5): 1206-1212.

[37] STEWART J E,KEAST R S. Recent fat intake modulates fat taste sensitivity in lean and overweight subjects[J]. International Journal of Obesity, 2012, 36(6): 834-842.

[38] STEWART J E,SEIMON R V,OTTO B,et al. Marked differences in gustatory and gastrointestinal sensitivity to oleic acid between lean and obese men[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2011, 93(4): 703-711.

[39] CHALÉRUSH A R,MATTES R D. Evidence for human orosensory(taste?)sensitivity to free fatty acids[J]. Chemical Senses, 2007, 32(5): 423-431.

[40] NEWMAN L P,KEAST R J. The test-retest reliability of fatty acid taste thresholds[J]. Chemosensory Perception, 2013, 6(2): 70-77.

[41] OZDENER M H,SUBRAMANIAM S,SUNDARESAN S,et al. CD36- and GPR120-mediated Ca2+signaling in human taste bud cells mediates differential responses to fatty acids and is altered in obese mice[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014, 146(4): 995-1005.

[42] STEWART J E,FEINLE-BISSET C,GOLDING M,et al. Oral sensitivity to fatty acids, food consumption and BMI in human subjects[J]. The British Journal of Nutrition, 2010, 104(1): 145-152.

[43] MATTES D R. Brief oral stimulation, but especially oral fat exposure,elevates serum triglycerides in humans[J]. AJP Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2009, 296(2): 365.

[44] HOPPERT K,ZAHN S,PUSCHMANN A,et al. Quantification of sensory difference thresholds for fat and sweetness in dairy-based emulsions[J]. Food Quality and Preference, 2012, 26(1): 52-57.

[45] KAWAI T,FUSHIKI T. Importance of lipolysis in oral cavity for orosensory detection of fat[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2003, 285(2): 447-454.

[46] HAMOSH M,SCOW R O. Lingual lipase and its role in the digestion of dietary lipid[J]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1973, 52(1): 88-95.

[47] PRIMEAUX S D, BRAYMER H D,BRAY G A. CD36 mRNA in the gastrointestinal tract is differentially regulated by dietary fat intake in obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats[J]. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 2013, 58(2): 363-370.

[48] PEPINO M Y,LOVE-GREGORY L,KLEIN S,et al. The fatty acid translocase gene CD36 and lingual lipase influence oral sensitivity to fat in obese subjects[J]. Journal of Lipid Research, 2012, 53(3): 561-566.

[49] KULKARNI B V,MATTES R D. Lingual lipase activity in the orosensory detection of fat by humans[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2014, 306(12): 879-885.

[50] GILBERTSON T A,LIU L,YORK D A,et al. Dietary fat preferences are inversely correlated with peripheral gustatory fatty acid sensitivity[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1998, 855(855): 165-168.

[51] DRANSFIELD E. The taste of fat[J]. Meat Science, 2008, 80(1): 37-42.

[52] ALFONSO V B,JULIO S C, SUSANA N K. Structured lipids in nutrition:a technology for the development of novelty products[J]. Revista Chilena De Nutrición, 2002, 29(2): 106-115.

[53] 黄赣辉. 味觉传感器阵列构建及其初步应用[D].南昌:南昌大学, 2006.

[54] TRAVERS S P,NICKLAS K. Taste bud distribution in the rat pharynx and larynx[J]. The Anatomical Record, 1990, 227(3): 373-379.

[55] ROPER S D. Taste buds as peripheral chemosensory processors[J]. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2013, 24(1): 71-79.

[56] LAUGERETTE F,PASSILLY-DEGRACE P,PATRIS B,et al. CD36 involvement in orosensory detection of dietary lipids, spontaneous fat preference, and digestive secretions[J]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2005, 115(11): 3177-3184.

[57] SCLAFANI A , ACKROFFK, ABUMRAD N A. CD36 gene deletion reduces fat preference and intake but not post-oral fat conditioning in mice[J]. AJP Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2007, 293(4): 61386.

[58] FUKUWATARI T,KAWADA T,TSURUTA M,et al. Expression of the putative membrane fatty acid transporter (FAT) in taste buds of the circumvallate papillae in rats[J]. FEBS Letters, 1997, 414(2): 461-464.

[59] CARTONI C,YASUMATSU K,OHKURI T,et al. Taste preference for fatty acids is mediated by GPR40 and GPR120[J]. The Journal of Neuroscience: the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2010, 30(25): 8376-8382.

[60] LIU P,SHAH B P,CROASDELL S,et al. Transient receptor potential channel type M5 is essential for fat taste[J]. The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2011, 31(23): 8634-8642.

[61] SIMONS P J,KUMMER J A,LUIKEN J J,et al. Apical CD36 immunolocalization in human and porcine taste buds from circumvallate and foliate papillae[J]. Acta Histochemica, 2011, 113(8): 839-843.

[62] GALINDO M M,VOIGT N,STEIN J,et al. G protein-coupled receptors in human fat taste perception[J]. Chemical Senses, 2012, 37(2): 123-139.

[63] BIGIANI A. Mouse taste cells with glialike membrane properties[J]. Journal of Neurophysiology, 2001, 85(4): 1552-1560.

[64] CLAPP T R,YANG R,STOICK C L,et al. Morphologic characterization of rat taste receptor cells that express components of the phospholipase C signaling pathway[J]. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 2004, 468(3): 311-321.

[65] BOTHAM K M, JONES W. Postprandial lipoproteins and the molecular regulation of vascular homeostasis[J]. Progress in Lipid Research, 2013, 52(4): 446-464.

[66] ASCH A S,BARNWELL J,SILVERSTEIN R L,et al. Isolation of the thrombospondin membrane receptor[J]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 1987, 79(4): 1054-1061.

[67] GHOSH A,LI W,FEBBRAIO M,et al. Platelet CD36 mediates interactions with endothelial cell-derived microparticles and contributes to thrombosis in mice[J]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2008, 118(5): 1934-1943.

[68] CORACI I S,HUSEMANN J,BERMAN J W,et al. CD36, a class B scavenger receptor, is expressed on microglia in Alzheimer’s disease brains and can mediate production of reactive oxygen species in response to beta-amyloid fibrils[J]. The American Journal of Pathology, 2002, 160(1): 101-112.

[69] MARTIN C,CHEVROT M,POIRIER H,et al. CD36 as a lipid sensor[J]. Physiology and Behavior, 2011, 105(1): 36-42.

[70] LE FOLL C,IRANI B G,MAGNAN C,et al. Characteristics and mechanisms of hypothalamic neuronal fatty acid sensing[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2009, 297(3): 655-664.

[71] SIMANTOV R,SILVERSTEIN R L. CD36: a critical anti-angiogenic receptor[J]. Frontiers in Bioscience: A Journal and Virtual Library, 2003, 8(1/3): 874-882.

[72] COLLOT-TEIXEIRA CS. CD36 and macrophages in atherosclerosis[J]. Cardiovascular Research, 2007, 75(3): 468-477.

[73] MEDLER K F,KINNAMON S C. Electrophysiological characterization of voltage-gated currents in defined taste cell types of mice[J]. Journal of Neuroscience the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2003, 23(7): 2608-2617.

[74] 葛漫丽,刘婷婷,王继红,等. B类清道夫受体CD36在脂代谢中的作用[J].中国免疫学杂志, 2013,9(11): 1219-1222.

[75] ZHANG X,FITZSIMMONS R L,CLELAND L G,et al. CD36/fatty acid translocase in rats: distribution, isolation from hepatocytes, and comparison with the scavenger receptor SR-B1[J]. Laboratory Investigation, 2003, 83(3): 317-332.

[76] CHEN C S,BENCH E M,ALLERTON T D,et al. Preference for linoleic acid in obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats is attenuated by the reduction of CD36 on the tongue[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2013, 305(11): 1346-1355.

[77] ZHANG X J,ZHOU L H,BAN X,et al. Decreased expression of CD36 in circumvallate taste buds of high-fat diet induced obese rats[J]. Acta Histochemica, 2011, 113(6): 663-667.

[78] CHEVROT M,BERNARD A,ANCEL D,et al. Obesity alters the gustatory perception of lipids in the mouse: plausible involvement of lingual CD36[J]. Journal of Lipid Research, 2013, 54(9): 2485-2494.

[79] MARTIN C,PASSILLY-DEGRACE P,GAILLARD D, et al. The lipid-sensor candidates CD36 and GPR120 are differentially regulated by dietary lipids in mouse taste buds: impact on spontaneous fat preference[J]. Plos One, 2011, 6(8): 24014.

[80] MARTIN C,PASSILLY-DEGRACE P,CHEVROT M, et al. Lipid-mediated release of GLP-1 by mouse taste buds from circumvallate papillae: putative involvement of GPR120 and impact on taste sensitivity[J]. Journal of Lipid Research, 2012, 53(11): 2256-2265.

[81] MASUDA D,HIRANO K I,OKU H,et al. Chylomicron remnants are increased in the postprandial state in CD36 deficiency[J]. Journal of Lipid Research, 2009, 50(5): 999-1011.

[82] STEWART J E,KEAST R J. Oral sensitivity to oleic acid is associated with fat intake and body mass index[J]. Clinical Nutrition, 2011, 30(6): 838-844.

[83] TUCKER R M,EDLINGER C,CRAIG B A,et al. Associations between BMI and fat taste sensitivity in humans[J]. Chemical Senses, 2014, 39(4): 349-357.

[84] 寿天德.神经生物学[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社,2003.

[85] HOLLIDAY N D,BROWN A H. Drug discovery opportunities and challenges at G protein coupled receptors for long chain free fatty acids[J]. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2011(2): 112.

[86] SUM C S,TIKHONOVA I G,NEUMANN S,et al. Identification of residues important for agonist recognition and activation in GPR40[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2007, 282(40): 29248-29255.

[87] DAVENPORT A P,HARMAR A J. Evolving pharmacology of orphan GPCRs: IUPHAR Commentary[J]. British Journal of Pharmacology, 2013, 170(4): 693-695.

[88] YONEZAWA T,KURATA R,YOSHIDA K,et al. Free fatty acids-sensing G protein-coupled receptors in drug targeting and therapeutics[J]. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 2013, 20(31): 3855-3871.

[89] 卢伊娜,胡慧,朱维良,等.GPR120的研究进展[J].生命科学,2008,20(2):275-278. LU Y N,HU H,ZHU W L,et al.Progress in GPR120 research[J].Chinese Bulletin of Life Sciences,2008,20(2):275-278.

[90] WETTSCHURECK N,OFFERMANNS S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions[J]. Physiological Reviews, 2005, 85(4): 1159-1204.

[91] DRANSE H J,HUDSON B D. Drugs or diet?Developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting the free fatty acid family of GPCRs[J]. British Journal of Pharmacology, 2013, 170(4): 696-711.

[92] BRISCOE C P,TADAYYON M,ANDREWS J L,et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR40 is activated by medium and long chain fatty acids[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2003, 278(13): 11303-11311.

[93] ITOH Y,KAWAMATA Y,HARADA M,et al. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40[J]. Nature, 2003, 422(6928): 173-176.

[94] KOTARSKY K,NILSSON N E,FLODGREN E,et al. A human cell surface receptor activated by free fatty acids and thiazolidinedione drugs[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2003, 301(2): 406-410.

[95] GODINOT N,YASUMATSU K,BARCOS M E,et al. Activation of tongue-expressed GPR40 and GPR120 by non caloric agonists is not sufficient to drive preference in mice[J]. Neuroscience, 2013, 250(8): 20-30.

[96] SUN Q,HIRASAWA A,HARA T,et al. Structure-activity relationships of GPR120 agonists based on a docking simulation[J]. Molecular Pharmacology, 2010, 78(5): 804-810.

[97] SCLAFANI A Z,ACKROFF K. GPR40 and GPR120 fatty acid sensors are critical for postoral but not oral mediation of fat preferences in the mouse[J]. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 2013, 305(12): 1490-1497.

[98] ABUMRAD N A. CD36 may determine our desire for dietary fats[J]. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2005, 115(11): 2965-2967.

[99] STRATFORD J M,CONTRERAS R J. Chorda tympani nerve transection alters linoleic acid taste discrimination by male and female rats[J]. Physiology and Behavior, 2006, 89(3): 311-319.

[100] PITTMAN D,CRAWLEY M E,CORBIN C H,et al. Chorda tympani nerve transection impairs the gustatory detection of free fatty acids in male and female rats[J]. Brain Research, 2007, 1151(3): 74-83.

[101] MATTES R D. Effects of linoleic acid on sweet, sour, salty, and bitter taste thresholds and intensity ratings of adults[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2007, 292(5): 1243-1248.

[102] GILBERTSONT A. Fatty acid responses in taste cells from obesity-prone and resistant rats[J]. Physiology and Behavior, 2006,86(5): 681-690.

[103] NINOMIYA Y. Regulation of food intake through modification of taste responsiveness:leptin,salivary proteins,fatty acids[R]. Japan: ILSI,1999.

[104] GREENBERG D,SMITH G P. The controls of fat intake[J]. Psychosomatic Medicine, 1996, 58(6): 559-569.

[105] DIPATRIZION V. Is fat taste ready for primetime?[J]. Physiology and Behavior, 2014,136: 145-154.

[106] DREWNOWSKI A,KURTH C,HOLDEN-WILTSE J, et al. Food preferences in human obesity: carbohydrates versus fats[J]. Appetite, 1992, 18(3): 207-221.

[107] DREWNOWSKI A. Why do we like fat? [J]. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 1997, 97(7): 58-62.

[108] MCCRORY M A,FUSS P J,MCCALLUM J E,et al. Dietary variety within food groups: association with energy intake and body fatness in men and women[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1999, 69(3): 440-447.

[109] BIRD R P,ALEXANDER J C. Cytotoxicity of thermally oxidized fats[J]. Vitro, 1981, 17(5): 397-404.

[110] HAMMOND E G,KLEYN D H. Off flavors of milk:nomenclature,standards,and bibliography1[J]. Journal of Dairy Science, 1978, 61(7): 855-869.

[111] MATTES R D. Oral fat exposure alters postprandial lipid metabolism in humans[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1996, 63(6): 911-917.

[112] MATTES R D. The taste of fat elevates postprandial triacylglycerol[J]. Physiology and Behavior, 2001, 74(3): 343-348.

[113] MATTES R D. Fat taste and lipid metabolism in humans[J]. Physiology and Behavior, 2005, 86(5): 691-697.

[114] HARYONO R Y,KEAST R S. Measuring oral fatty acid thresholds,fat perception,fatty food liking,and papillae density in humans[J]. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 2014(88): 51236.

[115] ASANO M,HONG G,MATSUYAMA Y,et al. Association of oral fat sensitivity with body mass index, taste preference, and eating habits in healthy Japanese young adults[J]. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 2016, 238(2): 93-103.

[116] NEWMAN L P,BOLHUIS D P,TORRES S J,et al. Dietary fat restriction increases fat taste sensitivity in people with obesity[J]. Obesity, 2016, 24(2): 328-334.

Is Fat Taste the Sixth Basic Taste?

WANG Xingguo, GAO Pan

(SchoolofFoodScienceandTechnology,JiangnanUniversity,Wuxi214122,China)

In recent years, fatty acids with the characteristics of the basic taste has been reported, and the point that fatty acids are the sixth basic taste has been proposed. Based on several aspects, such as electrophysiological characteristics of organisms, psychophysics characteristics, the main taste receptors, compared with other basic taste, the significance of fat taste, this paper reports that the evidence about the fat taste as the sixth basic taste is insufficient based on the existing literatures and the argument conditions of the basic taste.

fatty taste; fatty acid; basic taste

李 宁)

10.3969/j.issn.2095-6002.2016.05.001

2095-6002(2016)05-0001-11

王兴国,高盼. 脂肪味是第6种基本味觉吗?[J]. 食品科学技术学报,2016,34(5):1-11. WANG Xingguo, GAO Pan. Is fat taste the sixth basic taste?[J]. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2016,34(5):1-11.

2016-09-01

王兴国,男,教授,博士生导师,博士,主要从事油脂科学与技术方面的研究。

TS201.1

A