Meta-analysis of aspirin-heparin therapy for un-explained recurrent miscarriage

2016-10-13LingTongandXianjiangWei

Ling Tong*, and Xian-jiang Wei

Meta-analysis of aspirin-heparin therapy for un-explained recurrent miscarriage

Ling Tong1*, and Xian-jiang Wei2

1 Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, XiXi Hospital of Hangzhou, Hangzhou, 310023, China 2 Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital, Hangzhou 310000, China

recurrent miscarriage; aspirin; heparin; randomized controlled trials; meta-analysis

Objective This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of aspirin-heparin treatment for un-explained recurrent spontaneous abortion (URSA).

Methods Literatures reporting the studies on the aspirin-heparin treatment of un-explained recurrent miscarriage with randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were collected from the major publication databases. The live birth rate was used as primary indicator, preterm delivery, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, and adverse reactions (thrombocytopenia ) were used as the secondary indicators. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using RCT bias risk assessment tool in the Cochrane Handbook (v5.1.0). Meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan (v5.3) software. Subgroup analyses were conducted with an appropriately combined model according to the type of the treatments if heterogeneity among the selected studies was detected.

Results Six publications of RCTs were included in this study. There were a total of 907 pregnant women with diagnosis of URSA, 367 of them were pooled in the study group with aspirin-heparin therapy and 540 women in the control group with placebo, aspirin or progesterone therapy. Meta-analysis showed that the live birth rate in the study group was significantly different from that in the control group [= 1.18, 95%(1.00-1.39),=0.04]. Considering the clinical heterogeneity among the six studies, subgroup analysis were performed. Live birth rates in the aspirin-heparin treated groups and placebo groups were compared and no significant difference was found. There were no significant differences found between the two groups in the incidence of preterm delivery [=1.22, 95%(0.54-2.76),=0.64], preeclampsia [=0.52, 95%(0.25-1.07),=0.08], intrauterine growth restriction [=1.19, 95%(0.56-2.52),=0.45] and thrombocytopenia [=1.17, 95%(0.09-14.42),=0.90].

Conclusion This meta-analysis did not provide evidence that aspirin-heparin therapy had beneficial effect on un-explained recurrent miscarriage in terms of live birth rate, but it was relatively safe for it did not increase incidence of adverse pregnancy and adverse events. More well-designed and stratified double-blind RCT, individual-based meta-analysis regarding aspirin-heparin therapy are needed in future.

Chin Med Sci J 2016; 31(4):239-246

ECURRENT spontaneous abortion (RSA) generally refers to two or more times of fetal weight less than 500 g or fetal losses before 20th week of pregnancy with the same spouse. Incidence of RSA is about 1-5% in women at the childbearing age.1If the number of abortions increases in RSA patients, so does the possibility of consecutive abortion. The miscarriage rate after two abortions reaches higher than 50%. Thus additional intervene is necessary to prevent recurrent abortion.2,3Currently, RSA causes include chromosomal abnormalities, reproductive tract anatomical abnormalities, endocrine disorders, autoimmune factors, and infectious diseases etc., but still, over 50% patients in clinics are unknown of etiology or un-explained RSA (URSA).4

It has been believed that URSA is closely related to the prothrombotic state (PTS)5for the disordered coagulation and fibrinolytic system could cause recurrent miscarriage. PTS refers to the dysfunction or disorder of anticoagulation and fibrinolytic system in the body, and its presence in the blood can lead to the change in a variety of thrombosis factors, triggering the recurrent miscarriage.6Several studies have pointed out that aspirin-heparin therapy is potentially useful in improving situation of RSA patients.7,8Though effectiveness of aspirin-heparin treatment remains unclear, it is still considered as one of the therapy programs due to the lack of effective treatment options for URSA. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis evaluating the efficacy and safety of aspirin-heparin in the treatment of URSA in order to provide a comprehensive evaluation and clinical guidance.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion criteria

The research subjects needed to meet the diagnostic criteria for recurrent miscarriage, i.e. clinically two or more consecutive miscarriage before 20th week of pregnancy. Subjects with the following situations irrespective of ages were excluded from this study: couple chromosomal abnormalities, chromosomal abnormalities specimen abortion, family genetic history, maternal rep- roductive tract abnormalities, uterine anatomy of malfor- mations, maternal endocrine abnormalities, or recurrent spontaneous abortion due to environmental factors or other unknown causes.

The subjects in the study group received the aspirin-heparin therapy before or at the beginning of pregnancy. The subjects in the control group received placebo or treatments other than the aspirin-heparin.

The primary study aspect was the rate of live birth (the number of live births / the number of successful pregnancies). The secondary study aspects were incidence of adverse pregnancy reactions (i.e. thrombocytopenia) and outcomes (i.e. preterm delivery, preeclampsia, intrau- terine growth restriction).

Randomized controlled trials published in English or Chinese were included in the study regardless being blinded or not.

Exclusion criteria

The literatures were excluded if: (i) no clear diagnosis, inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study subjects; (ii) the study group was treated with other therapy programs other than the aspirin and heparin; (iii) obvious erroneous or incomplete data which could not provide the research outcomes; (iv) the duplicate publications.

Database search strategy

The databases includedPubMed (1966-2015.11), EMBASE (1980-2015.11), Science- Direct (1980-2015.11), OVID (1980-2015.11), China Nat- ional Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, 1980-2015.11), Chinese Scientific and Technical Journals Database (VIP, 1989-2015.11), and WanFang Electronic Journal Database (1998-2015.11). The retrieval time for the literature was up to November 2015.

The search terms in Chinese included "recurrent miscarriage", "recurrent abortion", "habitual miscarriage", "habitual abortion", "heparin", "aspirin", and "random". The search terms in English included "Abortion", "Habitual, Habitual Abortion, Recurrent Abortion, Miscarriage", "Recurrent, Abortion", "Recurrent, aspirin, heparin, Alloca- tion", "Random, Randomization Controlled Clinical Trials", "Randomized, Clinical Trials", "Randomized, Trials", and "Randomized Clinical".

Literature screening methods

The literature bibliographies were imported into the EndNote software (Ⅹ4, Thomson Corperation, USA) to recheck the information of volume, issue, summary, and hyperlink. Important information was compared, copied and edited, and bibliographies with the most complete information were retained. The literatures were initially screened to circle the ones matching the inclusion criteria. For those possibly not matching the inclusion criteria in their original language, the literatures were read and analyzed thoroughly to determine whether to include or not. Whether the literature was included, undetermined, or excluded with its reason were recorded in the notescolumn. The "pending" review articles were retroactively checked through their cited references. Two reviewers (LT and XW) independen- tly searched databases and evaluated studies for inclusion. Discrepancies regarding databases searching, inclusion decision or data interpretationwere resolved by discussions till consensuses were reached.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (LT and XW) independently evaluated the quality of the included studies by RCT bias risk assessment tool in the Cochrane Handbook (version 5.1.0) as recom- mended by the Cochrane Collaboration. The evaluation entries included seven aspects: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; applying blind to patients and treatment providers; applying blind to result evaluators; the data integrity; selective reporting on the results; and other sources of bias. The articles were then determined as "low risk", "high risk", or "unclear risk". Discrepancies on the quality assessment were resolved by discussions till consensuses were reached.

Data Extraction

A self-designed data extraction form was used. Extractions included the first author, year of publication, inclusion criteria for the study subjects, type of abortion, treatment options, comparable baseline, treatments for study and control groups, the number of patients in the groups and outcomes for study and control groups. At least two reviewers performed literature selection, quality assessment and data extraction. Disagreement, if occurred, was solved by consensuses after discussion.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using RevMan software (v5.3, Cochrane Collaboration). The binary data value in meta-analysis was assessed with relative risk () and its 95%. The heterogeneity among the various studies was measured with Chi-square study and its associated I2value. The fixed effects model was applied to merge the included studies for further analysis if no significant heterogeneity was detected (>0.1, I2≤50%). If the heterogeneity was significant (≤0.1, I2> 50%), the trials were sub-grouped according to the medicine used to analyze the sources of clinical heterogeneity. In case the sources of statistical heterogeneity could not be determined, the random effects model was applied to merge the included studies for further analysis.

RESULTS

Literature search results

A total of 336 literatures were originally extracted from the databases, and 249 of them were left after removing the duplicates. Initial screening by two reviewers on the research subjects, treatments, research type, title and abstract based on the screening criteria resulted in 34 literatures included, 8 literatures pended, and 196 literatures excluded. Among the 34 included literatures, 16 were written in English and 18 were in Chinese. Intensive reading further excluded 28 articles, so 6 RCTs were finally circled in this study,9-14including 4 in English and 2 in Chinese, with 907 URSA women involved in total (Fig. 1).

Quality assessment

In the six included studies, three used computer- generated random numbers for grouping,10-12one used random number table for grouping,9and the remaining twoonly mentioned the term "randomized" in the study design.13,14For the control of allocation concealment, one studyused telephone,9two studies used sealed opaque envelopes,11,12and the rest three did not mention allocation concealment. Only two studies mentioned double-blind in the study design.10,11None of the six studies had incomplete or selective data reporting. Four literatures did not mention how the sample sizes were estimated.9,12-14

The quality of these studies is high because only rando- mized controlled trials were included. Two studies met the principle of randomization, double-blind, comparability.10,11Strict trial inclusion criteria were employed in an effort to minimize multiple types of biases. The included trials were at low risk of bias for the method of randomization, alloca- tion concealment, attrition bias and selective reporting. Selection bias was decreased by the inclusion of only randomized studies and adequate allocation concealment. Performance bias was minimized because all studies with cointerventions were excluded, and the included trials tended to provide an adequate documentation of blinding to both investigators and participants. Overview of the quality evaluation results for included studies are shown in Fig. 2.

Basic information of the included literatures

There were 367 patients in study groups with aspirin- heparin therapy and 540 patients in the control groups with placebo or non-placebo therapy, respectively. The basic information in the included studies for the study and control groups were shown in Table 1. Patients age and number of abortions were comparable in all six studies. There are slight variations in study design including intervention used, control used, dose of administration, and therapy program. In studies of Clark9, Kaandorp10, Visser11and Elmahashi12, low molecular weight heparin(LMWH) plus aspirin were used as intervention- arm; in studies of Huijuan Wang13and Li Wang14, heparin plus aspirin were used as intervention-arm. For the control-arm, Clark9and Kaandorp10treated with placebo, and the remaining treated only with aspirin or conventional therapy such as progesterone.

The live birth ratein aspirin-heparin treated URSA women and the controls

The live birth rates reported in the six studies have been listed in Table 1. Totally 265 out of 367 URSA women in the study group with aspirin-heparin therapy and 337 out of 540 URSA women in the control group with placebo or non-placebo therapy gave successful live births respec- tively. Meta-analysis suggested significant heterogeneity across the studies (=0.02,2=63%), and the difference of live birth rate between the two groups was statistically significant using random effects model analysis [= 1.18, 95%(1.00-1.39),=0.04] (Fig. 3).

Considering that clinical heterogeneity among the treatments, subgroup analysis was performed according to the treatments in the control groups. There were two studies9,10with placebo treatment for the control groups, where the study and control groups both had 161 URSA women, and there were 114 and 113 successful live births respectively. No significant difference in the live birth rate revealed between the study and placebo control groups [= 1.00, 95%(0.87-1.15),= 0.98] (Fig. 4).

Figure 1. The process of screening literatures for Meta-analysis in this study.

Figure 2. Overview of the quality evaluation for the methodology of literatures included in this study.

Table 1. Basic information, adverse pregnancy outcomes and reactions in study and control groups

Figure 3. Comparison of live birth rate between the study group of aspirin-heparin and the control group of placebo as well as non-placebo.

Pregnancy outcomes and adverse reactions in heparin- aspirin treated URSA women and the controls

The adverse pregnancy outcomes and adverse reactions reported in the 6 studies has been shown in Table 1. Comparative analysis between the two groups was shown in Fig. 5. Four of the included studies have reported a total of 29 and 28 cases of preterm delivery out of 201 and 291 URSA women in the study and control groups respectively.10-13Meta-analysis showed no significant differences in the incidence of preterm delivery between the two groups [=1.22, 95%(0.54-2.76),=0.64]. Five studies reported a total of 9 and 21 cases of pree- clampsia out of 232 and 322 URSA women in the study and control groups respectively.10-14Meta-analysis also showed no significant differences in the incidence of preeclampsia between the two groups [=0.52, 95%(0.25-1.07),=0.08]. Two studies reported a total of 10 and 17 IUGR cases out of the 109 and 220 URSA women in the study and control groups respectively.10,11Again, Meta-analysis showed no significant differences in the incidence of IUGR between the two groups [=1.19, 95%(0.56-2.52),= 0.45]. Three studiesreported 6 cases of thrombocytopenia in both the study and control groups containing 192 and 287 URSA women respectively,9,10,14with no significant differences revealed between the two groups [=1.17, 95%(0.09-14.42),=0.90](Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Comparison of the live birth rate in aspirin-heparin treated groups and the placebo control groups.

Figure 5. Comparison of adverse reactions and pregnancy outcomes in heparin-aspirin treated groups and control groups.

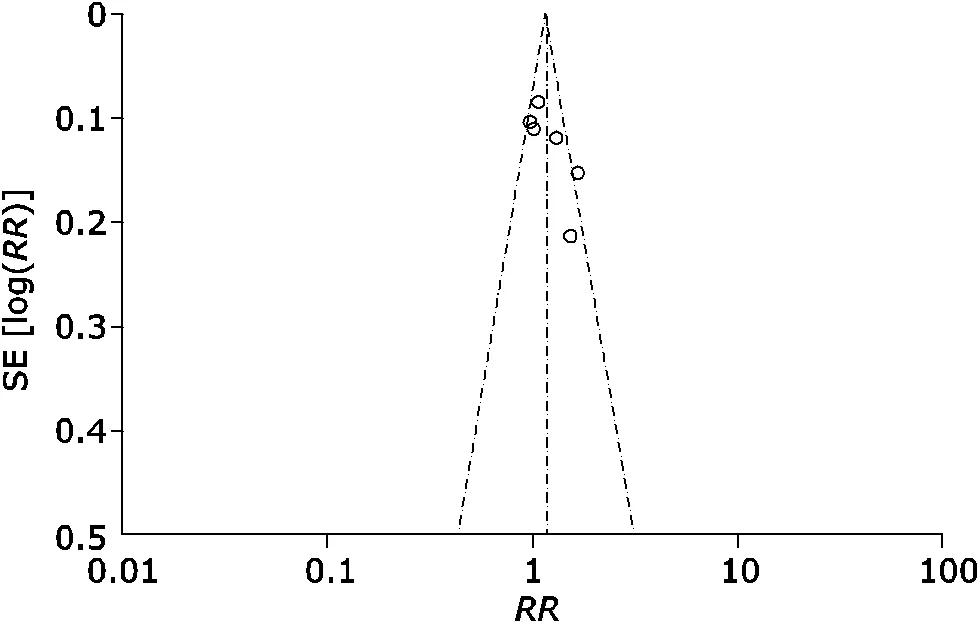

Publication bias

A funnel plot was used for reporting bias, which appeared asymmetric, suggesting that there may be publication bias (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. The funnel plot for live birth rate comparisons in heparin-aspirin therapy trials.

Discussions

Clinical significance of heparin-aspirin therapy

Mechanism of the recurrent miscarriage is complicated and treatment is always intractable. Recent evidence suggested that about one-third of recurrent miscarriage was related to immune factors and prothrombotic states. Pregnant women are generally in a blood hypercoagulable state, so vascular and microvascular thrombosis on the maternal- fetal interface can lead to miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, preeclampsia and other pathological phenomena of pregnancy.16At present, most scholars tend to believe that aspirin-heparin therapy is the most effective therapy to the recurrent miscarriage caused by the prothrombotic state.

Heparin carries a function of anticoagulation, antithro- mbosis, and protecting vascular endothelium etc. Its function is mainly achieved through inhibiting the activity of thro- mbin Ⅱa and coagulation factor Ⅹa. Although heparin cannot dissolve the clot, its anticoagulation function can prevent the development and recurrence of thrombosis, promoting autolysis of the early thrombus.17Compared to heparin, low molecular weight heparin has a better anti- thrombotic effect, higher bioavailability, longer duration of action, and less effect on platelets and blood lipids. Apart from inhibiting the cardiolipin antibodies and providing considerable therapy to the prothrombotic state, low molecular weight heparin is relatively safe to the fetus as it is not easy to pass through the placenta.18Aspirin belongs to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. It works by inhi- biting platelet cyclooxygenase to reduce prostaglandin production. This can decrease the tendency of thrombosis in patients, benefiting embryo implantation and reducing probability of recurrent abortion.19

By far, it is still inconclusive whether anticoagulation therapy should be used for the treatment of un-explained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Some clinicians tend to believe that anticoagulant therapy would benefit all kinds of RSA patients instead of just those accompanied with antiphospholipid syndrome. Whether there are evidences supporting beneficial effect of anticoagulants in women with URSA is the objective of this review.

Efficacy of aspirin- heparin therapy

Based on the six studies 907 cases of URSA women in this study, we found that the live birth rate between the aspirin- heparin treated groups and placebo or nonplacebo treated groups was statistically different with significant hetero- geneity. However, subgroup analysis did not show signi- ficant difference in live birth rate between the aspirin- heparin treated group and either placebo treated patients, LMWH treated patients, or aspirin treated patients respec- tively. The limited number of literatures and heterogeneity in these studies have to be taken into consideration. Study designs varied regarding doses of anticoagulants and prescription time periods, as well as using placebo or not in controls, which could result in impeded assessment of the risk-benefit ratio for the individual interventions.

To our knowledge, the efficacy of aspirin-heparin treat- ment for URSA has been only investigated in a systematic review by de Jong,15which indicated that evidence on the efficacy and safety of anticoagulants in women with URSA were undetermined. Comparatively, 3 of the 6 RCT studies in this review were relatively new and had not been analyzed. Thus we believe the results in this study is more comprehensive in terms of data volume.

Conclusively, there has still no evidence to support that aspirin and heparin can improve the live birth rate of patients with un-explained recurrent miscarriage.

Effects on adverse reactions and pregnancy outcomes

Preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia were also studied as adverse pregnancy outcomes in this study. We compared these pregnant outcomes between the study and control groups compre- hensively, and found that aspirin-heparin therapy did not improve pregnant outcomes of women with recurrent miscarriage. In addition, thrombocytopenia, as an indicator of adverse pregnancy and the main adverse event, was also comparable in the study and control group. Three of the included studies reported thrombocytopenia.9,10,14The comparison of outcomes in this study suggested that aspirin-heparin therapy is a relatively safe treatment, and does not increase the incidence of any adverse events in women with URSA, despite no beneficial effects on recurrent miscarriage has been found yet.

Bias on the included studies

In this meta-analysis we took efforts to eliminate potential publication bias, which enhanced the strength of the results. First, by extensive literature searching, we included a subs- tantial number of cases, which significantly increased the statistical power of our analysis. Second, two independent investigators performed the information extraction, data analysis, and quality assessments in our meta-analysis. However, funnel plot analysis for the includedstudies displayed asymmetry, which indicated the existence of potential publication bias. Two of the included studies did not provide specific methods for random sequence generation,13, 14four of them did not describe how the sample size was estimated,9,12-14three of themdid not mention allocation concealment,9,13,14and four of them did not use the blind method.9,10,13,14All these deficiencies could lead to bias and affect the result’s authenticity.

In summary, the present study suggests that the efficacy of aspirin-heparin therapy for un-explained recurrent miscarriage is still inconclusive. More randomized controlled trials in high-quality for further conclusion are in need. Design and conduction of clinical trials in future should focus on developing multi-center study with placebo as con-trol, ensuring randomized grouping, and utilizing evaluation standards that is internationally recognized.

1. Kuon RJ, Wallwiener LM, Germeyer A, et al. Establishment of a standardized immunological diagnostic procedure in RM patients. J Reprod Immunol 2012; 94:55.

2. Xiao SJ, Zhao AM. The etiology of recurrent spontaneous abortion research. Chin J Gynecol Obstet 2014; 30:41-5.

3. Cohen M, Bischof P. Factors regulating trophoblast invasion. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2007; 64:126-30.

4. Christiansen OB, Nybo Andersen AM, Bosch E, et al. Evidence-based investigations and treatments of recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril 2005; 83:821-39.

5. Luo QY, Chen BJ, Wu DJ, et al. Comparative analysis of the efficacy of five methods in treating the un-explained recurrent spontaneous abortion. China Prac Med 2009; 4:16-7.

6. Wang ZH, Zhang JP. Prothrombotic state with recurrent miscarriage and anticoagulant therapy. Chin J Gynecol Obstet 2013; 29:102-6.

7. Rai R, Backos M, Baxter N, et al. Recurrent miscarriage- an aspirin a day? Hum Reprod 2000; 15: 2220-3.

8. Brenner B, HoffmanR, Blumenfeld Z, et al. Gestational outcome in thrombophilic women with recurrent pregnancy loss treated by enoxaparin. Thromb Haemost 2000; 83: 693–7.

9. Clark, P, Walker ID, Langhorne P, et al. SPIN (Scottish Pregnancy Intervention) study: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial of low-molecular-weight heparin and low-dose aspirin in women with recurrent miscarriage. Blood 2010; 115:4162-7.

10.Kaandorp, SP.Goddijn M, van der Post JA, et al. Aspirin plus heparin or aspirin alone in women with recurrent miscarriage. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1586-96.

11.Visser J,Ulander VM, Helmerhorst FM, et al. Thrombo- prophylaxis for recurrent miscarriage in women with or without thrombophilia. HABENOX: a randomised multicentre trial. Thromb Haemost 2011; 105:295-301.

12.Elmahashi, MO Elbareg AM, Essadi FM, et al. Low dose aspirin and low-molecular-weight heparin in the treatment of pregnant Libyan women with recurrent miscarriage. BMC Res Notes 2014; 7: 23.

13.Wang HJ. Li ZY. Efficacy of heparin and aspirin in treating the un-explained recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Int Obstet & Gynecol 2014; 41: 207-8.

14.Wang L. Efficacy of the heparin and aspirin therapy for un-explained recurrent miscarriage. J Chin Prescription Drug 2014; 12:50.

15.de Jong PG, Kaandorp S, Di Nisio M. et al. Aspirin and / or heparin for women with unexplained recurrent miscarriage with or without inherited thrombophilia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 7: CD004734.

16.Allison JL, Schust DJ. Recurrent first trimester pregnancy loss: revised definitions and novel causes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2009; 16:446-450.

17.Qiu GX, Dai KR, Yang QM, et al. Expert advice on the prevention of deep venous thrombosis after major ortho- pedic surgery-abstract of the seminar about prevention of deep venous thrombosis. Chin J Orthop 2005; 10:636-40.

18.Dong XM, Du XZ, Zhao CS, et al. Research progress in thrombophilia and recurrent spontaneous abortion. Lab Med Clin 2013; 10: 197-200.

19.Yang QL, Mi JF. Application and development of aspirin in the treatment of recurrent miscarriage. Guide China Med 2011; 9: 41-2.

for publication January 31, 2016.

Tel: 86-0517-86481556, xxyylingtong@aliyun.com

杂志排行

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Frontal Absence Seizures: Clinical and EEG Analysis of Four Cases

- Clinical Observation of Bevacizumab Combined with S-1 in the Treatment of Pretreated Advanced Esophageal Carcinoma△

- Early Enteral Combined with Parenteral Nutrition Treatment for Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Effects on Immune Function, Nutritional Status and Outcomes△

- A Case Report of Acute Arterial Embolization of Right Lower Extremity As the Initial Presentation of Nephrotic Syndrome with Minimal Changes△

- Pseudohyperkalemia with Myelofibrosis after Splenectomy

- Uterine Artery Embolization for Management of Primary Postpartum Hemorrhage Associated with Placenta Accreta