Characteristics o f obese or overweight dogs visiting private Japanese vete rinary c linics

2016-09-07ShihoUsuiHidemYasudaYuzoKoketsuSchoolofAgricultureMeijiUniversityHigashimitaTamakuKawasakiKanagawa857JapanDepartmentofVeterinaryResearchandDevelopmentSpectrumLabJapanidorigaokaMegurokuTokyo3304Japan

Shiho Usui,Hidem i Yasuda,Yuzo Koketsu*School of Agriculture,MeijiUniversity,Higashi-mita --,Tama-ku,Kawasaki,Kanagawa 4-857,JapanDepartmentof Veterinary Research and Development,Spectrum Lab Japan,M idorigaoka -5--0,Meguro-ku,Tokyo 5-3304,Japan

Characteristics o f obese or overweight dogs visiting private Japanese vete rinary c linics

Shiho Usui1,Hidem i Yasuda2,Yuzo Koketsu1*1School of Agriculture,MeijiUniversity,Higashi-mita 1-1-1,Tama-ku,Kawasaki,Kanagawa 214-8571,Japan

2Departmentof Veterinary Research and Development,Spectrum Lab Japan,M idorigaoka 1-5-22-201,Meguro-ku,Tokyo 152-3304,Japan

Original article http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2016.01.011

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received in revised form 29 Dec 2015

Accepted 18 Jan 2016

Availableonline8Mar2016

Age

Canine

Factors

Obesity

Overweight

ABSTRACT

Ob jective:To characterize obese or overweight dogs that visited private Japanese veterinary clinics located in hum id subtropical climate zones.

M ethods:Dogs were categorized into four body condition score groups and fi ve body sizegroupsbased on theirbreed.Multilevel logistic regressionmodelswereapplied to the data.A Chi-squared test was used to exam ine whether the percentage of obese or overweight dogs differed between breeds.

Resu lts:There were 15.1%obese dogs and 39.8%overweight dogs.Obese dogswere characterized by increased age and female sex,whereas overweight dogs were characterized by increased age and neuter status(P<0.05).Peak probabilities of dogs being eitherobese oroverweightwerebetween 7 and 9 yearsof age,w ith the probabilities then declining as the dogs got older.For example,in toy sized dogs,the probability of dogs being overweight increased from 33.4%to a peak of 55.1%as dog age rose from 1 to 8 years old.A lso,inmedium,small and toy sized dogs,neutered dogsweremore likely to beoverweight than intact dogs,whereas neutered smallsized dogsweremore likely to be obese than intact small sized dogs(P<0.05).Additionally,the percentages of obese or overweight dogs differed between the 10 selected breedsw ith the highest percentage of obese or overweight dogs.

Conclusions:By taking age,body size,sex and neuter status into account,veterinarians can advise owners aboutmaintaining their dogs in ideal body condition.

1.Introduction

Numbers of obese and overweight people are increasing in developed countries[1,2].A lso,excessive body weight is a grow ing problem in dogs[3],and has been implicated in a range of medical concerns such as diabetes mellitus,cardiovascular diseases,dyslipidem ia and osteoarticular diseases[4–6].Dog obesity in developed countries is also a w idespread problem.The prevalence(%)of dogs being obese and overweight in the USA,the UK,Australia and China reported was estimated to be 34.1%[5],59.3%[7],25.0%[8]and 44.4% [9],respectively.

Factors commonly associated w ith dogs having excessive bodyweightarem iddle age,neutering,female sex,low physical activity and also low human population density[4,5,7,9].Speci fi c breeds,such as Labrador Retrievers,Beagles and Shetland Sheepdogs,have also been reported as being at highest risk of either obesity or being overweight[5,10].For example,Cocker Spaniels have been reported as having the highest risk for being overweight,whereas Shetland Sheepdogs were at the highest risk of obesity[5].

Dogs could also be categorized into different size groups based on theirbreed[4,11],such as large,medium and small size; this would take account of some breed effects.However,no studies in Japan have used medical records in a singlemodel to quantify the characteristic factors(body size,age,sex, neuter status and human population density)associated w ithdogs being either obese or overweight,and the interactions between these factors.

Dogs'veterinarymedical recordsare in amulti-levelstructure because health related checks,guidance and treatments on an individual dog are all performed in a clinic.The clinic is a variable that includes some unique information,such as a dog's location,the average social and econom ic status of owners com ing w ith their dogs to the clinic,and veterinary health guidance.Therefore,the objective of the present study was to exam ine characteristic or risk factors and interactions associated w ith obese dogsand overweightdogs in Japan by using am ixedeffectsmodelw ith clinics as a random intercept.

2.M aterials and m ethods

2.1.Dog database including dog characteristics and body condition score(BCS)

Institutional Animal Care and Use Comm ittee approval at MeijiUniversity(IACUC 15-0013)was obtained for this study. A dog database hasbeen created atMeijiUniversity(Kawasaki, Japan)by cooperating w ith a veterinary service(Spectrum Lab Japan,Tokyo,Japan).The veterinary service recorded information about individual dog's characteristics(BCS,age,sex, neuter status and breed)when they received serum samples for lipoprotein analysis from veterinarians in private clinics throughout Japan.The veterinarianswho subm itted the samples were not informed about the speci fi c purposes of the present study.The serum samples were collected from clinically nondiseased dogs that received a health check and from dogs that were being assessed for suspected dyslipidem ia.The dogs' health conditionswere diagnosed by their veterinarianswhen the serum sampleswere taken.The BCS for each dog was evaluated by the dog'sveterinarian using a fi ve-pointscale system(1:thin, 2:underweight,3:ideal,4:overweightand 5:obese).The BCS fi ve-pointscale system isw idely used in Japan[12],and website information and brochuresabout the system arew idely available to veterinary clinics across Japan,provided by the Pet Food Institute(Washington D.C.,USA)and a nutrition company [Hill's-Colgate(Japan)Ltd.,Tokyo,Japan].

2.2.Data and exclusion criteria

The database comprised data of 9 120 dogs from 116 breeds, collected from 1 198 veterinary clinics between 2006 and 2013, amounting to 10.9%of the 11 032 small animal clinics in Japan [12].The samples were subm itted from all the 47 prefecture regions,which aremostly located in hum id subtropical climate zones.The proportions of the samples in Northern Japan,East Japan(including Tokyo),West Japan and Kyushu were 9.6%, 56.7%,28.1%and 5.6%,respectively.Additionally,the proportions of the samples subm itted in January to March, April to June,July to September and October to December were 20.9%,29.5%,24.9%and 24.7%,respectively.

Recordsof second or later visitswere notused in the present study(2 170 records).Recordsof dogshaving diabetesmellitus, hypothyroidism or hyperadrenocorticism health problems, which would in fl uence body condition,were excluded from the dataset(563 records)if the veterinarianshadmadea diagnosisof endocrine diseases from blood and urinary tests,on the basis of clinical signs such as polydipsia and polyuria.A lso,the records of dogsw ith BCS 1 were excluded(12 records)because those dogswere few and were suspected of having a health problem. W ith the exception of the above exclusion criteria,all the other casessubm itted by theclinicswere included in the presentstudy.

Two datasets were created in the present study.Dataset 1 (including BCS 2,3,4 and 5 dogs)contained the records of 5 605 dogs in 108 breeds from 1 094 clinics,and was used to investigate characteristic factors associated w ith obese dogs.In Dataset 2(including only dogs of BCS 2,3 and 4),dogsw ith BCS 5 were excluded(844 records)because this dataset was used to exam ine factors only related to overweight dogs w ith BCS 4.Hence,Dataset 2 included the records of 4 761 dogs in 103 breeds from 1 020 clinics.

2.3.Categories and de fi nitions

Obeseand overweightdogswere de fi ned asdogshaving BCS 5 and BCS4,respectively.Additionally,dogswereclassi fi ed into two sex groups(male dogs or female dogs)and also two neuter statusgroups(intactdogsorneutered dogs).The dogs in the103 breedswere grouped into six body size categories(breed body size)based on theirbreed[6]:giant(e.g.SaintBernard),large(e.g. Labrador Retriever),medium(e.g.Beagle,Pembroke W elsh Corgi),small(e.g.M iniature Schnauzer,Shetland Sheepdog), toy(e.g.Chihuahua,M iniature Dachshund,Pomeranian,Shih Tzu,Yorkshire Terrier)and unknown.In the present study, giant sized dogs(23 records)were included in the large sized dog group because there were relatively few samples.Finally, the unknown group consisted ofmixed breed dogs.In addition, human population density(people per km2)valueswere based on the population density of the city where each clinic was located,and were obtained from the Statistics Bureau in the M inistry of InternalAffairsand Communications,Japan[13].

2.4.Statistical analysis

A ll statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc.,Cary,USA).Two-level analysis was applied,using a clinic at level2 and an individualdog at level1, to take account of the hierarchical structure of the individual dogsw ithin a clinic.A two-levelm ixed-effects logistic regression model,using the GLIMM IX procedure w ith logit link function,was performed to determ ine risk factors for obese or overweight dogs.A lso,ILINK(inverse link function)was used to convert the logit to a probability[14].Pairw ise multiple comparisonswere performed using the Tukey–Kramer test.

Outcome variables in Models 1 and 2,respectively,were whether or not dogs were obese(1 or 0;reference category=dogsw ith BCS 2–4),and whetherornotdogswere overweight(1 or 0;reference category=dogsw ith BCS 2 and 3).Age,sex,neuter status,breed body size groups and human population density were included in both Models as possible factors(explanatory variables).Quadratic expressions of continuous variables(e.g.age)and all possible Two-way interactions between explanatory variableswere also exam ined in both Models,and were then removed from the Models if they were not signi fi cant(P>0.10).The years when BCS was evaluated were taken as a fi xed effect in the Models,even though in prelim inary analysis the yearwas notassociated w ith the probability of dogs being obese or overweight(P≥0.11). Additionally,both Models included the clinic as a random intercept.To assess the variations in the probability of dogs being obese oroverweight thatcould be explained by the clinic,intraclass correlation coef fi cients(ICC)were calculated by the follow ing equation[15],

whereρrepresents the ICC,σ2Clinicis thebetween-clinic variance andπ2/3 is the assumed variance at the individual dog level. Normality of the residuals in the fi nalModelswas evaluated by using normal probability plots[14].Finally,for the 10 breeds w ith the highest percentages of obese or overweight dogs and w ith at least60 dogs in Dataset 1,a Chi-squared testwas used to examine whether or not the percentage of obese or overweight dogs differed between the 10 breeds.

3.Resu lts

BCS(mean±SEM)and median BCS in the 5 827 dogs, excluding BCS 1 dogs,were 3.6±0.01 and 4.0,respectively. A lso,mean ageatsamplingwas8.4±0.05,ranging from 0 to 18 years old.Relative frequencies(%)of BCS 2,3,4 and 5 were 3.7%,41.4%,39.8%and 15.1%,respectively(Table 1).M ean population density(people per km2)was 5 859±76 people, ranging from 29 to 21 882 people.

Obese dogs were characterized by increased age and being female,whereas overweight dogs were characterized by increased age and neuter status(Table 2;P<0.05).Increased age was non-linearly associated w ith a higher probability of dogs being obese or overweight(P<0.05).The probability of dogs being either obese or overweight peaked between 7 and 9 yearsofage,and then declined(Figure1).Femaledogswere1.3 times(odds ratio=1.3;P<0.01;Table 3)more likely to be obese than male dogs,but no such association was found between the groups for being overweight(P=0.29;Table 2).

Table1 Relative frequency of 5 605 dogs categorized on the basis of BCS*and breed body size.

Figure 1.Estimated probability of dogs being obese or overweight at differentage.

Table2 Estimatesof fi xed effects,random effect variance and ICC included in the fi nalmodels for the probability of dogs being obese or overweight*.

Breed body size groups were associated w ith obesity (P<0.01;Table 2),but not for being overweight(P=0.16; Table 2).Medium sized dogs were 1.4 timesmore likely to be obese than toy sized dogs(odds ratio=1.4;P=0.03;Table 3). In addition,there was a two-way interaction between dog ageand breed body size groups for the probability of dogs being overweight(P<0.01;Table 2).In toy sized dogs,the probability of dogs being overweight increased from 33.4%to a peak of 55.1%as dog age rose from 1 to 8 yearsold(Figure 2).A lso, inmedium sized dogs,the probability of dogs being overweight increased from 19.5%to a peak of 48.9%asdog age rose from 1 to 10 years old.

Table3 Com parisons between characteristic variables for the probability of dogs being obese or overweight.

Figure2.Estimated probability of dogs in differentbreed body sizegroups being overweightat different age.

Neuter status was associated w ith being overweight (P<0.01;Table 2),butnotw ith obesity(P=0.10).Neutered dogswere 1.4 times(odds ratio=1.4;P<0.01;Table 3)more likely to be overweight than intact dogs.Therewas a two-way interaction between neuter status and breed body size groups for the probability of dogs being obese(P=0.06;Table 2). Neutered small sized dogs weremore likely to be obese than intact small sized dogs(P<0.05;Table 4).In intact dogs, medium sized dogsweremore likely to be obese than the other sized dogs.However,for neutered dogs,there were no differences in the probabilities of large,medium,small and toy sized dogs being obese(Table 4).Also,there was a two-way interaction between neuter status and breed body size groups for the probability of dogs being overweight(P=0.02;Table 2). Neuteredmedium,small and toy sized dogsweremore likely to be overweight than respective sized intact dogs(P<0.05; Table 4).For intact dogs,there were no differences between breed body size groups for the probability of dogs being overweight(P≥0.10),whereas forneutered dogs,the small and toy sized dogs weremore likely to be overweight than large sized dogs(P<0.05).There was an association between overweight dogs and the population density of the cities where the clinics were located(P=0.04;Table 2),although there was no such association between obese dogs and city population density (P=0.20).

Table4 Comparisons between neuter status and breed body size groups for the probability of dogs being obese oroverweight.

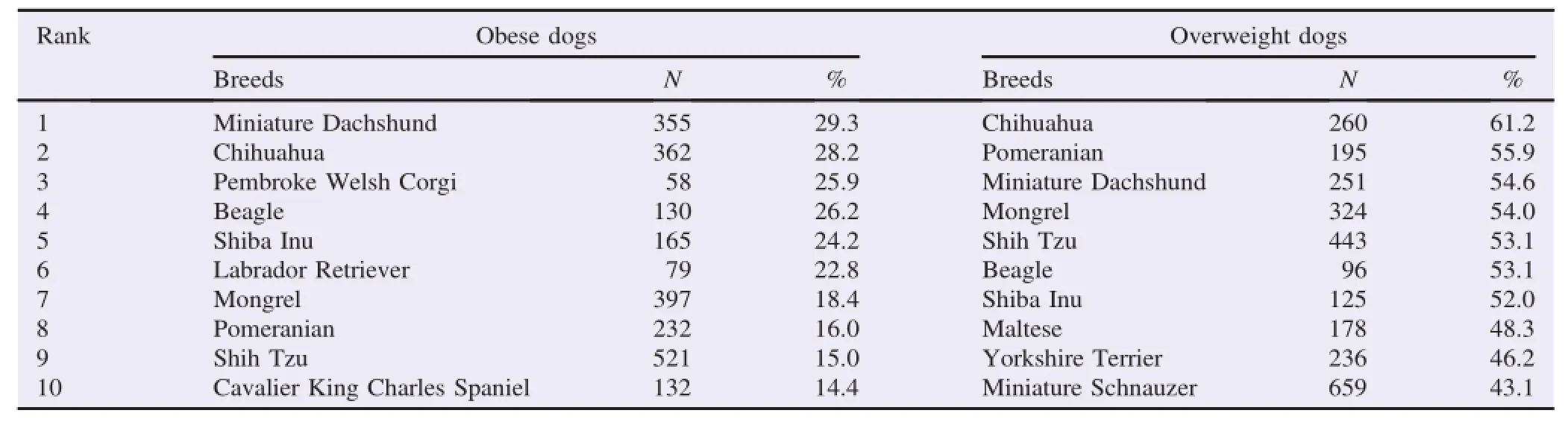

M iniature Dachshunds had the highest percentage in obese dogs,whereas Chihuahuas had the highest percentage in overweightdogs.A Chi-square testalso showed that therewere clear differences in the percentages of obese or overweight dogs between different breeds(P<0.05;Table 5).Finally,the ICC showed that the clinic effect explained 15.5%and 7.9%of the total variation for the respective probabilities of dogs being obese or overweight.

Table5 Top 10 breedsw ith the highest percentages of obese or overweight dogsoutof 103 breeds studied*.

4.Discussion

The present study quanti fi ed the effects of increased age on dogs being obese or overweight,and showed that the effects differed between breed body size groups for overweight dogs.It also showed that the probability of dogs being obese or overweight decreased from m iddle age in dogs of all sizes. Increasing age is related to decreasing physical activity,lean body mass and maintenance energy requirements[16,17].It appears that energy intake in some young to middle aged dogs of all sizes is not being managed appropriately by their owners.The decline from m iddle age in the probability of dogs in our study being obese or overweight m ight be explained by a decline in the appetite of dogs aged 7 years or older,as was found in a previous study[17].Another possible reason is that dogs of m iddle age or older are more likely to have unrecorded chronic disease that reduces their digestive capability and causesmoderate weight loss.

Furthermore,our study suggests that the changesw ith age in appetite,energy requirements and energy expenditure also depend on dog body size and breed[18].Our study revealed that medium sized dogs,including Beagles and Corgis,were 1.4 times more likely to be obese than toy sized dogs.Both Beagles and Corgis had 20%ormore obese dogs in our study. These fi ndings are consistent w ith another study that reported Beagles being prone to obesity[5].The breed differences of being obese appear to be related to genes related to fat metabolism which are hypothesized to be due to the breed selection process in dogs[19,20].

The high odds ratios of female dogs being obese in our study are consistentw ith the results of a previous study[9].Also,our study indicated that neutering accentuates the propensity for medium,small and toy sized dogs to be overweight and accentuates the propensity for small sized dogs to be obese. This could be explained by the fact that neutering appears to cause a reduced metabolic rate[17].Neutering predisposes dogs to having excessive body weight by reducing the concentrations of androgens and estrogens that act as satiety factors in the central nervous system[3].

Our study showed characteristic factors,including breeds,for obese dogswere not completely same as foroverweight dogs.A previous study analyzing speci fi c diseases related to obese and overweight dogs found some differences between obesity and being overweight for diseases[5].For example,diabetesmellitus was associated w ith obesity but not w ith being overweight, whereas hyperadrenocorticism(Cushing's disease)was related to being overweight but notw ith obesity[5].Being overweight may be a symptom different from obesity,and may have slightly different characteristics from obesity[7].A lso,our study indicates that breed and genetics differently affect the propensity of dogs being obese or overweight,as shown by the differences in the percentages of obese or overweight dogs between the 10 highest risk breeds.This could explain some of the difference in characteristics forbeing obeseoroverweight.

Our study showed the population density of the city where the dogs'clinicswere locatedwasassociatedw ith the probability of dogs being overweight,but notw ith the probability of them being obese.Previously,an Australian study using a three-point scale system(underweight,correct-weight or overweight)reported that dogs living in rural and sem i-rural areas were at greater risk of being overweight than urban dogs,due to high amounts of feeding and less exercise time[4,8].The sim ilar results in the two studies suggest that in Japan there is a difference in the lifestyles of dogs and their owners between rural and densely populated areas.

Our study is the fi rst report indicating relatively large differences between clinics in the probability of dogs being obese oroverweight,as indicated by the respective ICCs of 15.5%and 7.9%for clinic variance in the probability of dogs being obese and overweight.This suggests that there are relatively large explained effects of the clinic in relation to obese dogs,such as clinic location,dog owner's social status and veterinarians' guidance for dogs'dietary and exercisemanagement[21,22].

In conclusion,our study characterized obese or overweight dogs by age,sex,neutering status and breed body size.This fi nding could help veterinarians to improve their advice to owners on how to maintain their dogs in ideal body condition, by taking age,body size or dog breed,and neuter status into account.

Finally,it should be noted that there are some lim itations in this present study.Dogswere not random ly selected because it was a cross-sectional study using veterinarian-subm itted samples from private clinics.Consequently,there was a lack of information on diseases affecting BCS(e.g.protein losing nephropathy)because we did not collect speci fi c disease data except for endocrine diseases.Our studymay include dogsw ith false positive test results of endocrine diseases,and diseased dogswhich were not tested due to subtle clinical signs.Additionally,the dogs'rearing environments and nutrition were not taken into account in the analyses.The level of agreement between the BCS evaluations conducted by the participating veterinarians was not evaluated.However,our statistical modelsincluded the clinic as a random effect.Even w ith such lim itations,this research provides valuable information for veterinarians about the risk factors related to dog obesity and being overweight.

Con fl ict of interest statement

We declare thatwe have no con fl ictof interest.

Acknow ledgm ents

The authorsgratefully thank the cooperating veterinarians for providing their data for use in the present study.W e also thank Dr.I.M cTaggart for his critical review of thismanuscript.This work was supported by the Research Project Grant(Giken 2012–2016 A)from Meiji University.

References

[1]Sandøe P,Palmer C,Corr S,Astrup A,B jørnvad CR.Canine and feline obesity:a One Health perspective.VetRec 2014;175:610-6.

[2]Osto M,Lutz TA.Translational value of animalmodels of obesityfocus on dogs and cats.Eur J Pharmacol 2015;759:240-52.

[3]Zoran DL.Obesity in dogs and cats:a metabolic and endocrine disorder.Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract2010;40:221-39.

[4]Robertson ID.The association of exercise,diet and other factors w ith owner-perceived obesity in privately owned dogs from metropolitan Perth,WA.Prev Vet Med 2003;58:75-83.

[5]Lund EM,A rm strong PJ,Kirk CA,Klausner JS.Prevalence and risk factors for obesity in adult dogs from private US veterinary practices.Int JAppl Res VetMed 2006;4:177-86.

[6]Xenoulis PG,Steiner JM.Lipid metabolism and hyperlipidem ia in dogs.Vet J 2010;183:12-21.

[7]Courcier EA,Thom son RM,M ellor DJ,Yam PS.An epidemiological study of environmental factors associated w ith canine obesity.J Small Anim Pract2010;51:362-7.

[8]M cGreevy PD,Thom son PC,Pride C,Fawcett A,Grassi T, Jones B.Prevalence of obesity in dogs examined by Australian veterinary practices and the risk factors involved.Vet Rec 2005; 156:695-702.

[9]M ao J,Xia Z,Chen J,Yu J.Prevalence and risk factors for canine obesity surveyed in veterinary practices in Beijing,China.Prev Vet Med 2013;112:438-42.

[10]Corbee RJ.Obesity in show dogs.JAnim Physiol Anim Nutr 2013; 97:904-10.

[11]Okafor CC,Pearl DL,Lefebvre SL,W ang M,Yang M,Blois SL, et al.Risk factors associated w ith struvite urolithiasis in dogs evaluated atgeneral care veterinary hospitals in the United States. JAm VetMed Assoc 2013;243:1737-45.

[12]Usui S,Yasuda H,Koketsu Y.Characteristics of dogs having diabetesmellitus;analysis of data from private Japanese veterinary clinics.Vet Med Anim Sci2015;3:5.

[13]Statistics Bureau.M inistry of Internal Affairs and Communications.Tokyo:Statistics Bureau;2013.[Online]Available from: http://www.stat.go.jp/english/index.htm[Accessed on 26th November,2015]

[14]Littell RC,M illiken GA,Stroup WW,Wol fi nger RD, Schabenberger O.SAS for mixed models.2nd ed.Cary:SAS Institute Inc.;2006.

[15]Dohoo I,M artin W,Stryhn H.Veterinary epidemiologic research. 2nd ed.Charlottetown:VER Inc.;2009.

[16]Speakman JR,van Acker A,Harper EJ.Age-related changes in the metabolism and body com position of three dog breeds and their relationship to life expectancy.Aging Cell 2003;2:265-75.

[17]La fl amme DP.Companion animals symposium:obesity in dogs and cats:what is w rong w ith being fat?J Anim Sci 2012;90: 1653-62.

[18]Bermingham EN,ThomasDG,CaveNJ,MorrisPJ,Butterw ick RF, German AJ.Energy requirements of adult dogs:a meta-analysis. PLoSOne 2014;9(10):e109681.

[19]Jeusette I,Greco D,Aquino F,Detilleux J,Peterson M,Romano V, etal.Effectof breed on body composition and comparison between variousmethods to estimate body composition in dogs.Res Vet Sci 2010;88:227-32.

[20]Sw itonski M,M ankow ska M.Dog obesity–the need for identifying predisposing geneticmarkers.Res Vet Sci2013;95:831-6.

[21]Bland IM,Guthrie-Jones A,Taylor RD,Hill J.Dog obesity:veterinary practices'and owners'opinions on cause and management. Prev VetMed 2010;94:310-5.

[22]Chauvet A,Laclair J,Elliott DA,German AJ.Incorporation of exercise,using an underwater treadm ill,and active clienteducation into a weight management program for obese dogs.Can Vet J 2011;52:491-6.

10 Dec 2015

*Corresponding author:Yuzo Koketsu,Schoolof Agriculture,MeijiUniversity, Higashi-m ita 1-1-1,Tama-ku,Kawasaki,Kanagawa 214-8571,Japan.

Tel:+81 44 934 7826

Fax:+81 44 934 7902

E-mail:koket001@isc.meiji.ac.jp

This study was conducted in accordance to theM eijiUniversity AnimalW elfare Guidelines for Experimental Animals and was approved by Institutional Anim al Care and USE Comm ittee at M eiji University(IACUC 15-0013).

Foundation Project:Supported by the Research ProjectGrant(Giken 2012–2016 A)from M eiji University.

The journal imp lements double-blind peer review practiced by specially invited internationaleditorial boardmembers.

Peer review under responsibility of Hainan Medical University.

2221-1691/Copyright©2016 Hainan Medical University.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.This is an open accessarticle under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Sudden death in a captive mee rkat(Suricata surica tta)w ith arterial m edial and m yocardial calcification

- Salivary leptin concentrations in Bruneian secondary school children

- Risk factors from HBV infection among blood donors:A system atic review

- Com putational in telligence in tropicalm edicine

- The African Moringa is to change the lives ofm illions in Ethiopia and far beyond

- Pediculosis capitis among p rimary and m idd le school children in Asadabad,Iran:An epidem iological study