ENSO冷暖位相影响东亚冬季风与东亚夏季风联系的非对称性

2016-07-27徐霈强冯娟陈文

徐霈强冯娟陈文

1中国科学院大气物理研究所季风系统研究中心,北京1001902中国科学院大学,北京100049

ENSO冷暖位相影响东亚冬季风与东亚夏季风联系的非对称性

徐霈强1, 2冯娟1陈文1

1中国科学院大气物理研究所季风系统研究中心,北京100190

2中国科学院大学,北京100049

摘 要东亚冬季风(East Asian Winter Monsoon,简称EAWM)和东亚夏季风(East Asian Summer Monsoon,简称EASM)作为东亚季风系统的两个组成部分,他们之间存在显著的转换关系。前人的研究表明EAWM与次年EASM的转换关系只有在ENSO事件发生时才显著,然而这些研究都是基于ENSO对大气环流的影响是对称的这一假设下进行的。本文的研究表明EAWM和次年EASM的转换关系在ENSO冷暖事件中存在着明显的不对称性。通过将EAWM分为与ENSO有关的部分(EAWMEN)和与ENSO无关的部分(EAWMRES),我们发现在强EAWMEN年(即La Niña年),在西北太平洋会存在一个从冬季维持到次年夏季的气旋性环流异常(the anomalous western North Pacific Cyclone,WNPC),从而造成EASM偏弱;而在弱EAWMEN年(即El Niño年时),在西北太平洋会存在一个从冬季维持到次年夏季的反气旋性环流异常(the anomalous western North Pacific anticyclone,WNPAC),从而引起次年EASM偏强。比较而言,WNPAC的位置比WNPC的位置偏南,且强度更强,因而在El Niño年能够引起次年 EASM 更大幅度的增强。造成这一不对称联系的主要原因是热带太平洋和印度洋异常海温的演变差异。在强EAWMEN年,热带太平洋的负海温异常衰减地较慢,使得在次年夏季仍然维持着显著的负异常海温;相反,在弱EAWMEN年,热带太平洋的正海温异常衰减地较快,以至于在次年夏季的异常海温信号已经基本消失,但此时印度洋却有着显著的暖海温异常。海温演变的差异进一步造成了大气环流的差异,从而导致 EAWM与次年EASM联系的不对称性。

关键词东亚冬季风 东亚夏季风 ENSO 不对称性

徐霈强,冯娟,陈文. 2016. ENSO冷暖位相影响东亚冬季风与东亚夏季风联系的非对称性 [J]. 大气科学, 40 (4): 831-840. Xu Peiqiang, Feng Juan, Chen Wen. 2016. Asymmetric roles of ENSO in the link between the East Asian winter monsoon and the following summer monsoon [J]. Chinese Journal of Atmospheric Sciences (in Chinese), 40 (4): 831-840, doi:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.1509.15192.

1 引言

东亚是世界上最大的季风区,在夏季盛行的偏南风将热带西太平洋和印度洋的水汽输送至中国东部、日本以及朝鲜半岛,造成这些区域的持续性强降水(Tao and Chen, 1987; Ding, 1993; Chen et al., 2009)。东亚夏季风(East Asian summer monsoon, EASM)的变异常常会给东亚地区带来严重的气候灾害,如 1998年夏季长江流域的特大洪涝灾害(Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2007)和2006年夏季重庆地区所遭受的百年不遇的酷暑和干旱。因此,预测东亚夏季风的年际变率就成为了气候预测中的重要问题(Ding, 1992; Zhou et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2007)。

EASM的变化,除了受到大气内部变率的影响,还会受到许多外强迫的影响,如海表面温度(SST)、雪盖、土壤湿度和青藏高原的热力情况等(Charney and Shukla, 1981; Wu and Ni, 1997; Huang et al., 2003)。在众多的影响因子中,厄尔尼诺—南方涛动(El-Niño–Southern Oscillation, ENSO)普遍被认为是最重要的因子之一(Charney and Shukla, 1981; 吴国雄和孟文, 1998; Chen et al., 1992; 黄荣辉和陈文, 2002; 黄荣辉等,2003; Huang et al., 2003)。研究表明当El Niño处于发展阶段时,华南和华北地区的降水会减少,而华中地区的降水会增多;当El Niño处于消亡阶段,情况则大致与此相反(Huang and Wu, 1989; Huang et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2007)。

然而除了ENSO之外,东亚冬季风(East Asian winter monsoon, EAWM)对EASM的变异也有重要的指示意义。早在20世纪90年代我国学者就已经发现EAWM与EASM之间存在联系,但是这种联系,尤其在降水场上,统计信度并不高(Sun and Sun, 1994)。随后的研究考虑了海洋在EAMM和EASM联系中的重要作用。Wang and Wu(2012)考虑了印度洋海温在EAWM对EASM影响中的桥梁作用。然而,Chen et al.(2000)、陈文(2002)和Chen et al.(2013)的一系列研究强调了ENSO在 EAWM 和 EASM 联系中的重要作用。其中 Chen et al. (2013)的研究指出,当El Niño事件发生时,在西北太平洋地区会有一个从冬季维持到次年夏季的异常反气旋(the anomalous western North Pacific anticyclone, WNPAC),WNPAC西部的偏南风能减弱冬季EAWM的偏北风,加强(减弱)次年夏季EASM的偏南风,从而建立起EAWM与次年EASM之间的紧密联系;然而在非 El Niño年,由于WNPAC只能在冬季维持,因此 EAWM与次年EASM之间的联系并不能建立。

以上的研究都是基于大气对ENSO的响应是对称的这一前提下开展的,然而El Niño和La Niña本身在振幅、结构以及时间演变上就存在着不对称性(Hoerling et al., 1997; Burgers and Stephenson, 1999; Kang and Kug, 2002; Jin et al., 2003; An and Jin, 2004; An et al., 2005; Wu et al. 2010)。此外,数值试验的结果表明即使用大小相同、符号相反的SST异常也能强迫出不对称的大气环流异常(Hoerling et al., 1997; Kang and Kug, 2002)。Zhang et al.(1996)的研究指出ENSO对西北太平洋地区的大气环流影响只在 El Niño发生时显著,而Zhang et al.(2015)进一步的研究工作指出这主要是因为东亚季节内振荡(Intraseasonal Oscillation, ISO)的活动在 ENSO处于不同位相时的显著差异。当La Niño事件发生时,ISO的活动会更加频繁,因此便削弱了La Niño事件所强迫出的年际变化的振幅。

鉴于以上讨论,我们便会提出这样一个问题:当ENSO处于不同位相时,EAWM与EASM之间的联系是否也存在着不对称性?本文将对该问题进行分析。

2 资料与方法

本文中所使用的数据来自于欧洲数值预报中心(European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, ECMWF)提供的45年(1957年9月至2002年8月)逐月平均的再分析资料ERA-40。其水平网格距为 2.5°×2.5°,在垂直方向上共 23层(1000 hPa至1 hPa)(Uppala et al., 2005)。文章中所使用的海表温度数据来自于英国哈德莱中心(Met Office Hadley Center),该资料覆盖了1870年1月以来的全球海冰和海表温度,水平分辨率为1° ×1°(Rayner et al., 2003)。除此之外,本文还使用了中国气象局提供的全国160个台站的逐月降水资料,该数据起始于1951年1月。除特殊说明外,所有的数据在分析前都去除了线性趋势。

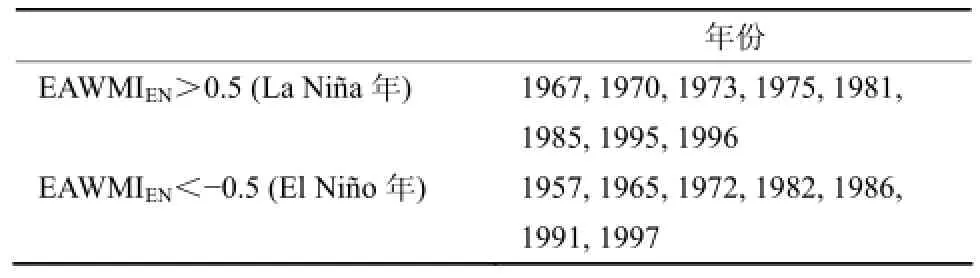

本文使用Yang et al.(2002)定义的EAWM指数(EAWMI)来表征EAWM的强弱。该指数定义为850 hPa的经向风速在(20°~40°N, 100°~140°E)区域内的平均。然后我们依照Chen et al.(2013)的方法将EAWMI分成两部分:与ENSO相关的部分(EAWMIEN)和与 ENSO 无关的部分(EAWMIRES)。与ENSO相关的部分用线性回归的方法得到(图1),与ENSO无关的部分是EAWMI减去EAWMIEN后的残差。Chen et al.(2013)的研究表明只有与ENSO相关的EAWM异常部分才能对次年 EASM产生影响,因此本文主要分析与ENSO相关的EAWM异常部分(即EAWMEN)对次年EASM的不对称影响。这里我们将EAWMIEN乘以了−1使得正指数对应于强EAWMEN年。强(弱)冬季风年的选取标准为EAWMIEN大于(小于)0.5(−0.5)倍标准差。根据此标准我们选取了8个强EAWMEN事件和7个弱EAWMEN事件(见表1)。由于EAWMIEN是由Nino3指数进行线性回归后所得到的,所以强东亚冬季风年(即EAWMIEN>0.5)也就对应于La Niña年,而弱的东亚冬季风年(即EAWMIEN<−0.5)便对应于El Niño年。本文主要通过合成分析方法,探究与ENSO相关的EAWM对次年EASM的不对称影响。

表1 冬季风偏强/偏弱年的选取年份Table 1 Years of selected cases of strong and weak EAWMEN

3 EAWMEN与次年EASM联系的不对称性

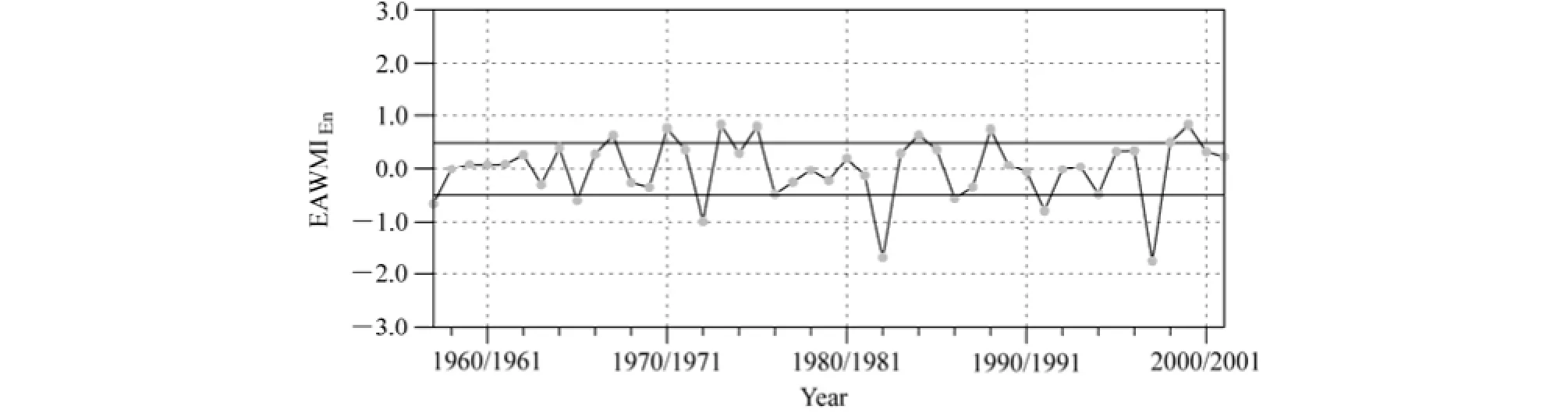

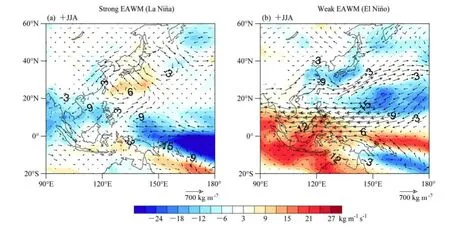

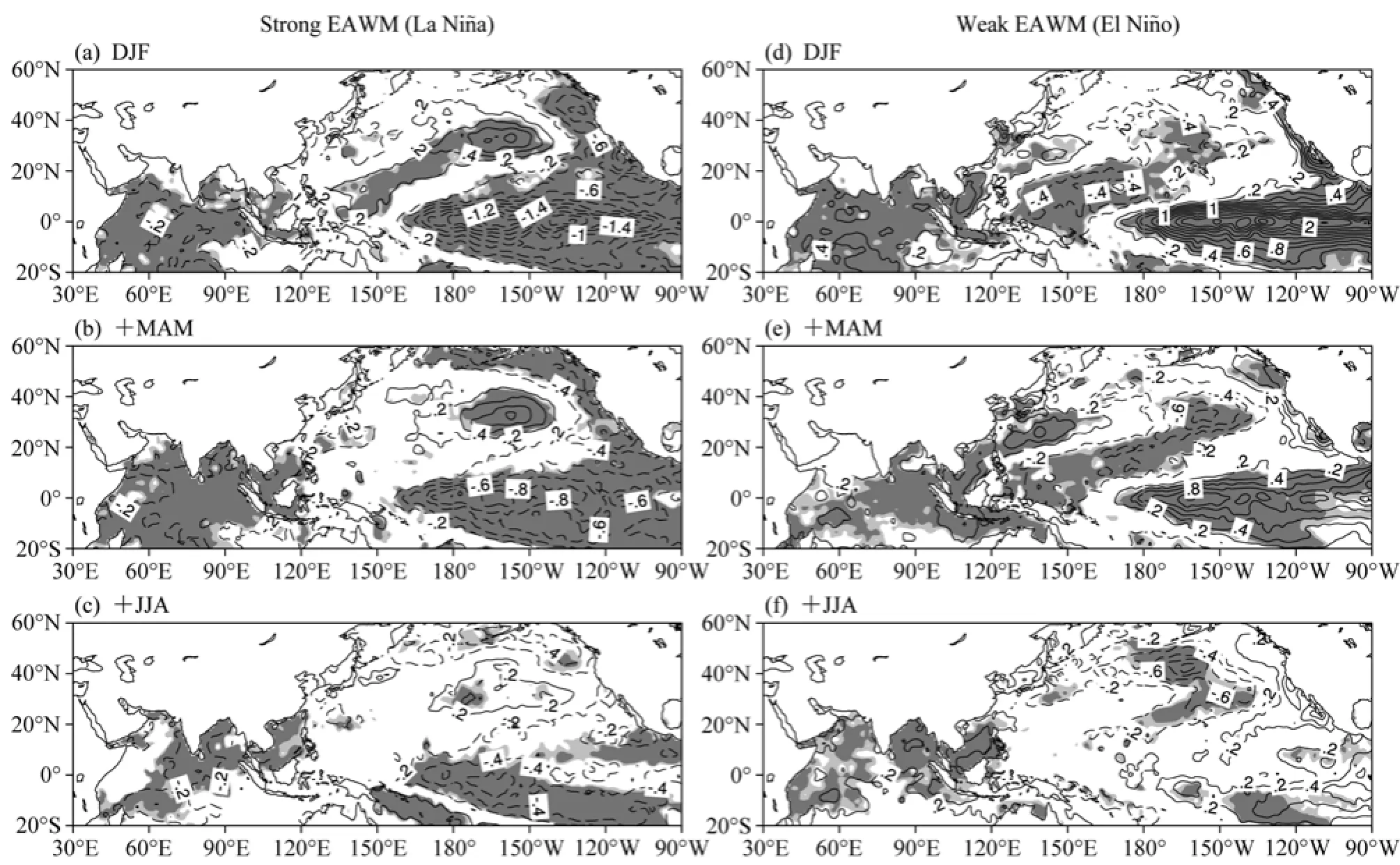

为了说明El Niño 和La Niña事件在EAWMEN和次年EASM联系中的不对称作用,图2给出了当El Niño和La Niña事件分别发生时,850 hPa流函数异常场和风矢量异常场从冬季到次年夏季的演变特征。从图中可以看出在强 EAWMEN年(即当La Niña发生时),在西北太平洋地区附近存在一个异常的气旋性环流(the anomalous western North Pacific cyclone, WNPC),WNPC能从冬季一直维持到次年夏季(图2a–c),但是随着WNPC的强度逐渐减弱,至次年夏季时 WNPC的强度已经较弱。WNPC西部的偏北风阻碍了西南夏季风的北进,造成次年 EASM 强度偏弱(图 2c)。相反地在弱EAWMEN年(即当El Niño发生时)在菲律宾附近存在着一个从冬季持续到次年夏季的WNPAC,尽管从冬季到次年春季WNPAC的强度有所减弱,但其后基本能维持较大的强度(图2d–f)。WNPAC西部的偏南风增强了东亚夏季的西南季风(图 2f),从而造成次年EASM偏强。

对比图2a–c和图2d–f可见,WNPC和WNPAC无论在强度上还是在覆盖面积上都存在着显著的不对称性,这在次年夏季表现地尤为突出。WNPAC 比WNPC的强度强,覆盖范围更广,位置也更偏南。因此当El Niño事件发生时,EAWM与次年EASM之间有着紧密的联系;然而在La Niña事件发生时,随着WNPC的快速减弱,EAWM与次年EASM之间的联系也随之减弱。

图1 与ENSO相关的东亚冬季风指数从1957/1958冬季至2001/2002年冬季的标准化时间序列。这里1957/1958年表示1957/1958年的冬季Fig. 1 Time series of normalized EAWMIEN(ENSO-related part of EAWM) averaged for December–February from 1957/1958 to 2001/2002 (the year 1957/1958 denotes the 1957/1958 winter)

图2 在La Niña年850 hPa流函数场(等值线;单位:106m2s−1)和850 hPa风场(矢量;单位:m s−1)异常的合成图:(a)冬季(DJF);(b)春季(+MAM);(c)夏季(+JJA)。(d, e, f)同(a, b, c)但为El Niño年的情况。浅灰和深灰分别表示流函数t检验通过了0.1和0.05的显著性水平区域,等值线间隔为0.4×106m2s−1Fig. 2 Composite seasonal mean 850-hPa streamfunction (contours; units: 106m2s−1) and 850-hPa wind (vectors; units: m s−1) anomalies in La Niña years for (a) DJF (December–February), (b) +MAM (March–May) and (c) +JJA (June–August); (d–f) as in (a–c) but for El Niño years. Light and dark shadings indicate statistical significance for streamfunction at the 90% and 95% confidence levels, respectively, according to a two-tailed Student’s t test; contour interval = 0.4×106m2s−1)

图3 合成的次年夏季850 hPa流函数异常(等值线;单位:106m2s−1)与850 hPa风场异常(矢量;单位:m s−1)在La Niña年和El Niño年的不对称部分。浅灰和深灰分别表示流函数t检验通过了0.1和0.05的显著性水平区域,等值线间隔为0.4×106m2s−1Fig. 3 Composite summation of 850-hPa streamfunction (contours; units: 106m2s−1) and wind (vectors; units: m s−1) anomalies in the following summer between La Niña and El Niño years. Light and dark shadings indicate statistical significance for streamfunction at the 90% and 95% confidence levels, respectively, according to a two-tailed Student’s t test; contour interval = 0.4×106m2s−1

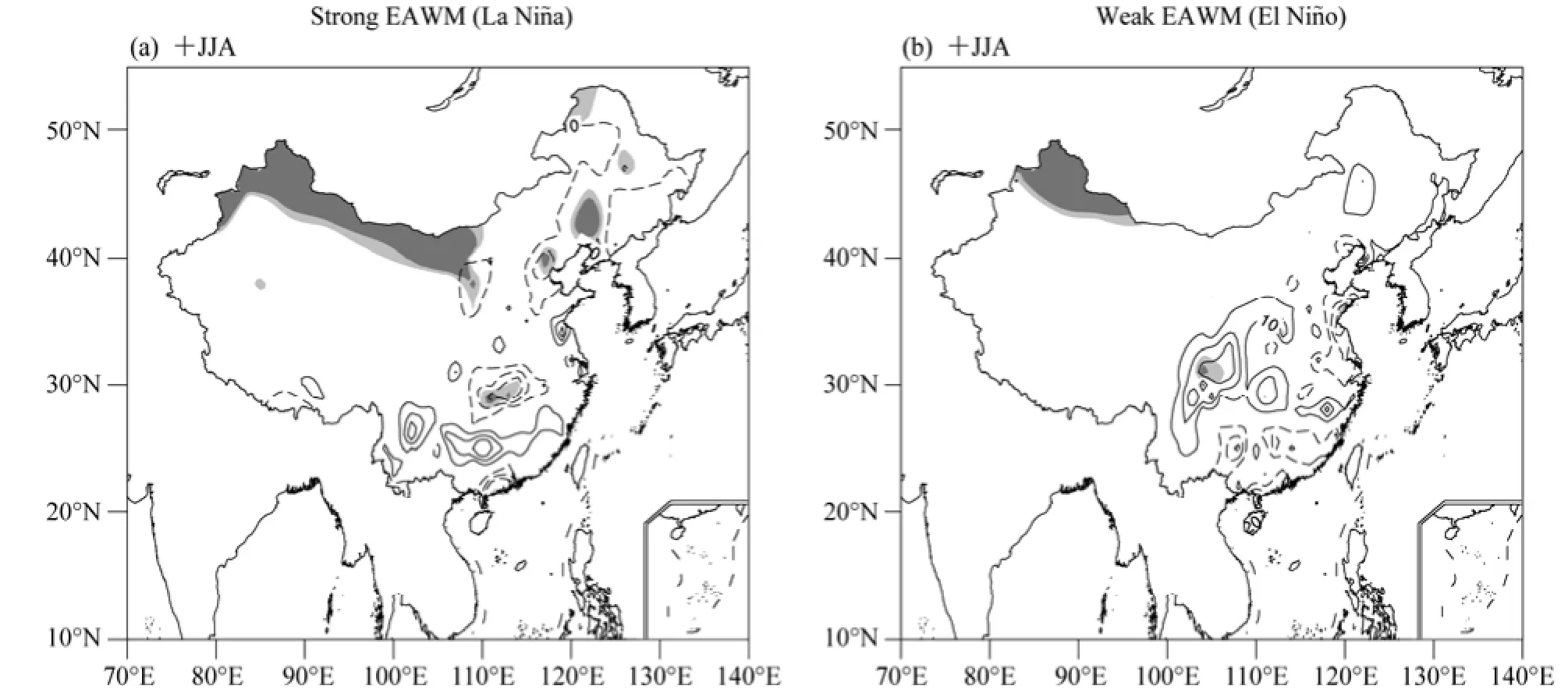

图4 中国降水异常(a)La Niña年和(b)El Niño年的次年夏季的合成图(单位:mm month−1)。虚线表示降水为负异常,浅灰和深灰分别表示t检验通过了0.1和0.05的显著性水平,等值线间隔为10 mm month−1Fig. 4 Composite rainfall anomalies (units: mm month−1) in China for the decaying summers of (a) La Niña and (b) El Niño years (dashed lines denote negative values; contour interval = 10 mm month−1; light and dark shadings indicate statistical significance at the 90% and 95% confidence levels, respectively, according to a two-tailed Student’s t test)

为了进一步说明 ENSO在EAWM与次年EASM联系中的不对称性作用,图3给出了ENSO处于不同位相时850 hPa流函数异常场和风矢量异常场在次年夏季相加的结果。这里我们用此结果来近似代表流函数场异常和风矢量场异常的不对称部分。可以看出在西太平洋地区存在显著的反气旋性环流,其北侧存在一个弱的气旋性环流。这进一步证明了WNPAC比WNPC的位置偏南,且异常强度更强。

EAWMEN与次年EASM的不对称联系不仅表现在大气环流场上,还表现在降水场上。图4是在La Niña年和El Niño年,次年夏季中国异常降水的分布图。从图中可以看出,在 La Niña年,即EAWMEN偏强时,次年夏季中国东北及长江流域地区的降水偏少;在El Niño年,即EAWMEN偏弱时,次年夏季的异常降水主要位于长江流域。此外,无论在是El Niño年还是La Niño年,降水异常场上通过信度检验的区域均较少,这与 Zhang et al. (1999)的结论是一致的。这主要是因为影响中国降水年际变化的因子有很多,而ENSO只是众多因子中的一个(Ding, 1993)。

此降水异常的分布主要是由水汽输送的差异所致。图5给出了当La Niña事件或者El Niño事件发生时,次年夏季水汽含量及水汽输送异常的合成图。当La Niña 事件发生时,WNPC阻碍了夏季西南季风对水汽的向北输送,导致中国东北至东部沿海地区对流层中水汽含量的减小,从而造成降水偏少;而当El Niño事件发生时,WNPAC加强了东亚地区西南季风对水汽的向北输送,导致长江流域水汽含量的增加,从而造成降水偏多。

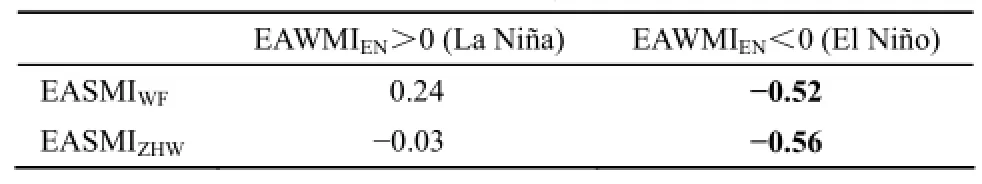

为了进一步地证明ENSO在EAWMEN与次年EASM转换中的不对称作用,我们计算了EAWMIEN与选取的两个EASM指数(EASMI)的相关系数(表2)。在这里我们选取了两个能表征EASM不同环流特征的 EASMI:第一个 EASMI(这里称为EASMIWF)定义为850 hPa的纬向风场在(22.5°~32.5°N,110°~140°E)与(5°~15°N,90°~130°E)区域的平均值之差,这个指数反映了WNP对流层低层的切边涡度(Wang and Fan, 1999);第二个EASMI(这里称为EASMIZHW)定义为850 hPa和 200 hPa的纬向风场在(0°~10°N,100°~130°E)区域的平均值之差,该指数旨在通过用纬向风场的垂直切变来表征南北方向的热力对比(祝从文等,2000)。从表 2可以看出,当 EAWMEN偏强时,EAWMIEN与次年EASMI的相关系数均较低;而当EAWMEN偏弱时,EAWMIEN与次年EASMI的相关系数均较高。这意味着当EAWMEN偏弱时,次年夏季的WNPAC强度要更强,且南北方向上的温度差异也会更加明显,这均表示次年EASM会有更大幅度的增强。

图5 同图4,但是为整层积分的水汽含量(填色;单位:kg m−1s−1)和水汽输送通量(矢量;单位:kg m−2)。Fig. 5 As in Fig. 4 but for vertically integrated water vapor flux (vectors; units: kg m−1s−1) and moisture content (color shading; units: kg m−2).

表2 强弱EAWMIEN与不同EASM指数的相关系数,粗体表示t检验通过了0.10的显著性水平Table 2 Correlation coefficients between EAWMIENand the two selected EASM indices (bold values indicate statistical significance at the confidence level greater than 90%, based on the Student’s t test)

4 可能机制分析

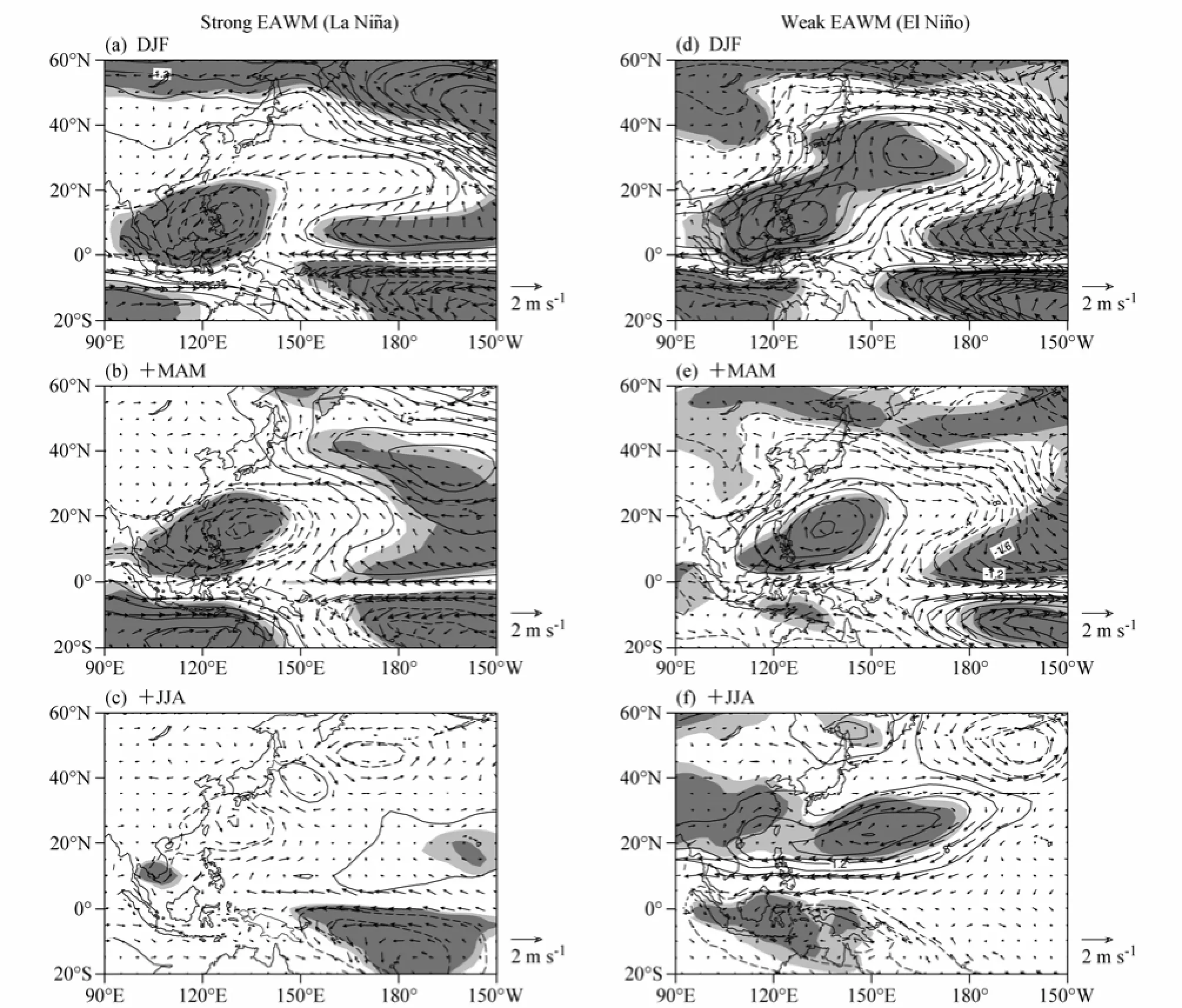

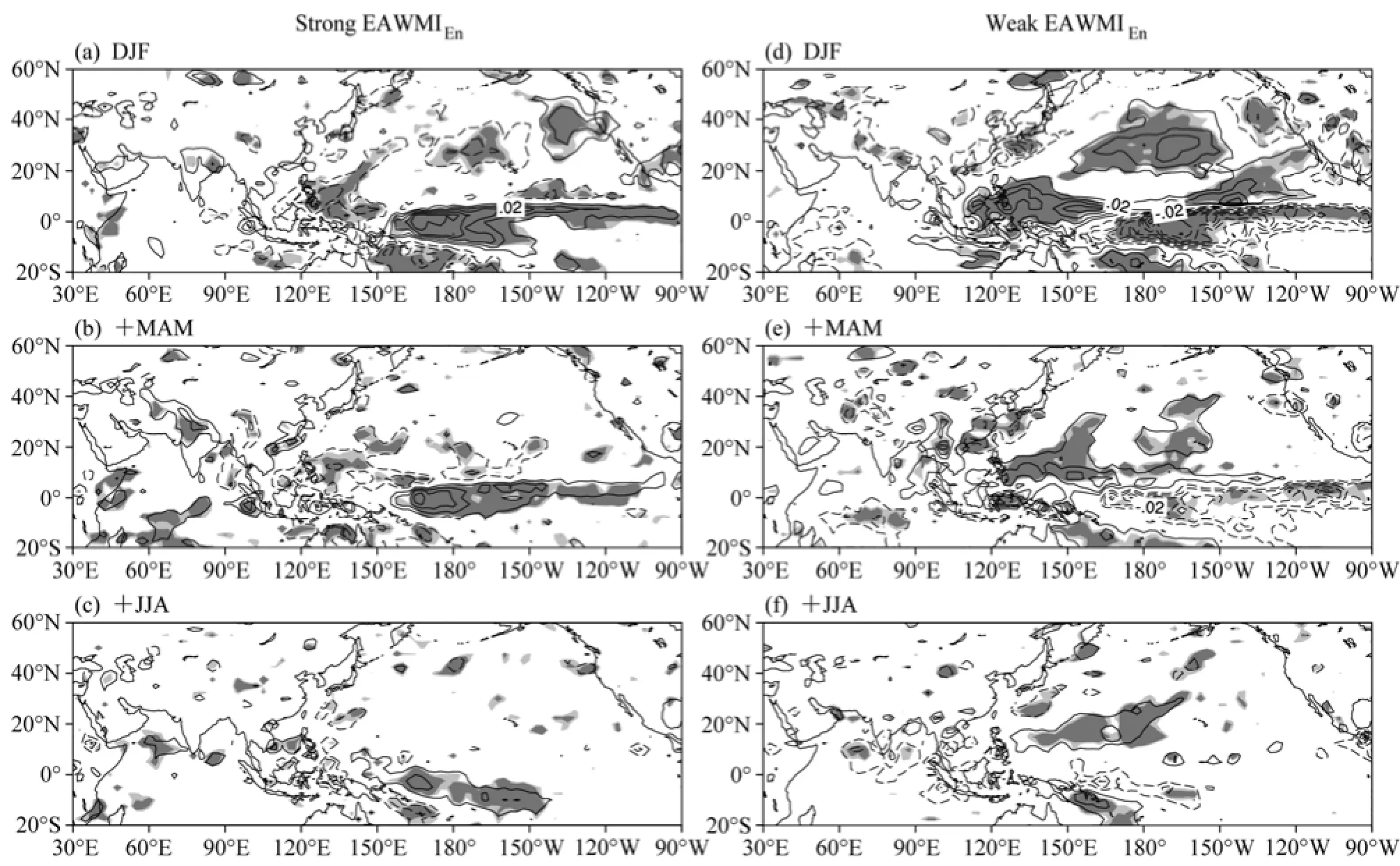

由以上的分析可知,WNPC和WNPAC是连接EAWM和次年EASM的关键性系统,既然热带海温是该环流系统维持的主要外强迫因子,那么热带海温是如何在La Niña和El Niño年演变的?又是如何引起WNPC和WNPAC的不对称性的?为了弄清这些问题,图6给出了La Niña年和El Niño年从冬季到次年夏季热带异常海温的合成演变图。以往的研究表明当ENSO事件发生时,在菲律宾附近的非绝热冷却(加热)产生Gill响应(Gill, 1980),从而导致其西北侧形成的反气旋性环流异常(气旋性环流异常)(Zhang et al., 1996)。然而菲律宾附近的非绝热冷却(非绝热加热)一方面会受到局地海温的影响,另一方面,热带中东太平洋的海温异常也能通过强迫出的异常 Walker环流从而在西北太平洋地区引起异常的下沉(上升)运动,导致非绝热冷却(加热)的发生(Zhang et al., 1996; Wang and Zhang, 2002)。从冬季到次年春季,无论是在El Niño年还是在La Niña年,在热带中东太平洋都维持着显著的正海温异常(负海温异常)(图 6a、b和图6d、e)。因此由该异常海温所强迫出的异常Walker环流能引起西太平洋地区空气的下沉(上升)(图7a、b和图7d、e),在菲律宾附近产生非绝热冷却(加热),从而造成WNPAC(WNPC)的维持(图2a、b 和图2d、e)。另外在西太平洋地区,局地异常海温的作用也不可忽视。在El Niño(La Niña)事件发生时,从冬季到次年春季西太平洋附近维持的负(正)海温异常也可以引起西太平洋地区附近的下沉(上升)运动,从而导致菲律宾附近的非绝热冷却(加热)。

图6 La Niña年海温异常(单位:°C)在(a)冬季(DJF)、(b)春季(+MAM)和(c)夏季(+JJA)的合成图。(d, e, f)同(a, b, c)但为El Niño年的情况。浅灰和深灰分别表示t检验通过了0.1和0.05的显著性水平区域,等值线间隔为0.2°CFig. 6 Composite seasonal mean SST (contours; units: °C) anomalies during La Niña years for (a) DJF, (b) +MAM, and (c) + JJA; (d–f) as in (a–c) but for El Niño years. Light and dark shadings indicate statistical significance at the 90% and 95% confidence levels, respectively, according to a two-tailed Student’s t test; contour interval = 0.2°C

但是在次年夏季,两者在中东太平洋的异常海温却表现出较大的差异(图6c、f)。在La Niña事件发生时,赤道中东太平洋在次年夏季依然维持着显著的负异常海温(图 6c),因此仍然能在热带中太平洋强迫出异常的下沉运动,在西太平洋强迫出异常的上升运动。由于其异常海温的强度已经显著减弱(图7c),因此该异常海温所强迫出的WNPC也随之减弱。然而在El Niño事件发生时,中东太平洋的正海温异常衰减地较快,以至于在次年夏季的信号已经基本消失(图 6f)。因此太平洋地区的海温异常已经不是WNPAC维持的主要强迫因子。值得注意的是,此时的热带印度洋有显著的异常正海温。Xie et al.(2009)揭示了印度洋异常海温在维持WNPAC中的作用(即印度洋电容器理论),他们指出热带印度洋的海温异常能通过深对流活动引发上空的对流层大气进行干绝热调整,引起印度洋上空的对流层温度升高,从而激发出向东传播的斜压开尔文波。向东传播的暖开尔文波能引起西北太平洋地区近地面产生异常的东北风,从而诱使副热带地区的风场发生辐散并抑制该地区的对流活动,最终造成WNPAC的维持。因此当ENSO处于次年夏季的衰亡期时,印度洋的异常海温是维持西北太平洋地区异常环流的主要原因。由于在 La Niña事件发生时,次年夏季印度洋地区的负海温异常强度较弱,因此WNPC的强度也较弱。

另外,局地海气相互作用也是维持 WNPAC (WNPC)的另一个机制(Wang et al., 2000; Wang and Zhang, 2002)。Wang et al.(2000)研究指出“风—蒸发—SST反馈”是局地海温维持西北太平洋反气旋环流的一个重要机制。由于北半球低纬度近地面盛行东北信风,因此反气旋东部的偏北风会增强东北信风的风速,从而加大西北太平洋海洋表面的蒸发,引起海表冷却。此异常的负海温又能通过产生Gill模态(Gill, 1980)从而在其西侧激发出新的反气旋异常,使得海温进一步冷却。由于在东亚沿岸地区反气旋西部的异常南风会减弱东北信风的风速,从而引起沿岸地区的海表温度增暖。西北太平洋异常海表温度的偶极子结构有利于上述“风—蒸发—SST”反馈机制的维持,使得WNPAC能在El Niño消亡期维持。由图6可见,在El Niño年,西太平洋的偶极子结构能从冬季持续到次年夏季,因此局地海气相互作用的正反馈机制有利于WNPAC的维持。然而,在La Niña年,西太平洋的偶极子结构较弱,因此局地海气相互作用的正反馈机制强度较弱,对WNPC的维持作用也较小。由此可见,热带太平洋和印度洋海温演变的差异是造成EAWM与次年EASM不对称联系的主要原因。

图7 同图6,但为500 hPa p坐标系的垂直速度。等值线间隔为0.01 Pa m−1Fig. 7 Same as in Fig. 6, but for 500-hPa vertical velocity in p ordinate (contour interval = 0.01 Pa m−1)

5 结论与讨论

本文利用欧洲中心提供的 ERA-40再分析资料、英国哈德莱中心提供的海表温度数据以及中国气象局提供的逐月降水资料分析了 ENSO在EAWM与次年EASM转换中的不对称作用,并得到了以下的结论。

在EAWMEN偏强的年份(即La Niña事件发生时),会存在一个从冬季维持到次年夏季的WNPC,从而造成次年EASM强度的减弱;在EAWMEN偏弱的年份(即El Niño事件发生时),会存在一个从冬季维持到次年夏季的WNPAC,但较之于WNPC,其位置更偏南,而且强度更强。这使得EASM异常的区域在El Niño年偏南,且异常的强度更强。

造成这一不对称联系的主要原因是由于ENSO处于不同位相时热带太平洋和印度洋的海温演变差异。在EAWMEN偏强的年份,热带太平洋的异常负海温衰减地较慢,使得在次年夏季仍然维持着显著的异常负海温。该异常海温能在热带中太平洋强迫出异常的下沉运动,在西太平洋强迫出异常的上升的运动。由于此异常Walker环流的上升支能产生菲律宾附近异常的非绝热加热,从而有利于WNPC的维持。在EAWMEN偏弱的年份,热带中东太平洋的正海温异常衰减地较快,以至于在次年夏季的信号已经基本消失,但此时印度洋却维持着显著的暖海温异常,增暖的印度洋能通过激发向东传播的暖Kelvin波从而继续维持WNPAC。

局地海气相互作用的差异也是造成 WNPC和WNPAC不对称的原因。在La Niña年,局地海气相互作用的反馈过程比 El Niño年弱,从而导致WNPC比WNPAC的强度弱,使得EAWM与次年EASM之间联系的不对称性进一步增大。

自上世纪80年代以来,中太平洋型(CP型)ENSO事件发生频率明显增多,而CP型ENSO事件与东太平洋型(EP型)ENSO事件无论是在演变过程还是在对全球气候的影响上均有较大差异(Feng et al., 2011, Chen et al., 2014, Chen et al., 2015)。因此在未来的研究中,有必要在把 ENSO事件划分为EP型ENSO事件与CP型ENSO事件,从而进一步分析EAWM与次年EASM之间转换关系的不对称性。

参考文献(References)

An S I, Jin F F. 2004. Nonlinearity and asymmetry of ENSO [J]. J. Climate, 17 (12): 2399–2412, doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<2399:NAAOE> 2.0.CO;2 .

An S I, Ham Y G, Kug J S, et al. 2005. El Niño–La Niña asymmetry in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project simulations [J]. J. Climate, 18 (14): 2617–2627, doi:10.1175/JCLI3433.1.

Burgers G, Stephenson D B. 1999. The “normality” of El Niño [J]. Geophys. Res. Lett., 26 (8): 1027–1030, doi:10.1029/1999GL900161.

Charney J G, Shukla J. 1981. Predictability of Monsoons [M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 99–110.

陈文. 2002. El Niño和La Niña事件对东亚冬、夏季风循环的影响 [J]. 大气科学, 26 (5): 595–610. Chen Wen. 2002. Impacts of El Niño and La Niña on the cycle of the East Asian winter and summer monsoon [J]. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. (in Chinese), 26 (5): 595–610, doi:10.3878/j.issn. 1006-9895.2002.05.02.

Chen L X, Dong M, Shao Yongning. 1992. The characteristics of interannual variations on the East Asian monsoon [J]. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 70 (1B): 397–421.

Chen W, Graf H F, Huang R H. 2000. The interannual variability of East Asian winter monsoon and its relation to the summer monsoon [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 17 (1): 48–60, doi:10.1007/s00376-000-0042-5.

Chen W, Wang L, Xue Y K, et al. 2009. Variabilities of the spring river runoff system in East China and their relations to precipitation and sea surface temperature [J]. Int. J. Climatol., 29 (10): 1381–1394, doi:10. 1002/joc.1785.

Chen W, Feng J, Wu R. 2013. Roles of ENSO and PDO in the link of the East Asian winter monsoon to the following summer monsoon [J]. J. Climate, 26 (2):622-635, doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00021.1.

Chen Z S, Wen Z P, Wu R G, et al. 2014. Influence of two types of El Niños on the East Asian climate during boreal summer: A numerical study [J]. Climate Dyn., 43 (1–2): 469–481, doi:10.1007/s00382-013-1943-1.

Chen Z S, Wen Z P, Wu R G, et al. 2015. Relative importance of tropical SST anomalies in maintaining the western North Pacific anomalous anticyclone during El Niño to La Niña transition years [J]. Climate Dyn., doi: 10.1007/s00382-015-2630-1.

Ding Y. 1993. Monsoons over China [M]. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 419.

Ding Y H. 1992. Summer monsoon rainfalls in China [J]. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 70 (1B): 373–396.

Feng J, Chen W, Tam C Y, et al. 2011. Different impacts of El Niño and El Niño Modoki on China rainfall in the decaying phases [J]. Int. J. Climatol., 31 (14): 2091–2101, doi:10.1002/joc.2217.

Gill A E. 1980. Some simple solutions for heat-induced tropical circulation [J]. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 106 (449): 447–462, doi:10.1002/ qj.49710644905.

Hoerling M P, Kumar A, Zhong M. 1997. El Niño, La Niña, and the nonlinearity of their teleconnections [J]. J. Climate, 10 (8): 1769–1786, doi:10.1175/1520-0442(1997)010<1769:ENOLNA>2.0.CO;2.

黄荣辉, 陈文. 2002. 关于亚洲季风与 ENSO循环相互作用研究最近的进展 [J]. 气候与环境研究, 7 (2): 146–159. Huang Ronghui, Chen Wen. 2002. Recent progresses in the research on the interaction between Asian monsoon and ENSO cycle [J]. Climatic and Environmental Research (in Chinese), 7 (2): 146–159, doi:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9585. 2002.02.03.

Huang R H, Wu Y F. 1989. The influence of ENSO on the summer climate change in China and its mechanism [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 6 (1): 21–32, doi:10.1007/BF02656915.

Huang R H, Zhou L T, Chen W. 2003. The progresses of recent studies on the variabilities of the East Asian monsoon and their causes [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 20 (1): 55–69, doi:10.1007/BF03342050.

黄荣辉, 陈文, 丁一汇, 等. 2003. 关于季风动力学以及季风与ENSO循环相互作用的研究 [J]. 大气科学, 27 (4): 484–502. Huang Ronghui, Chen Wen, Ding Yihui, et al. 2003. Studies on the monsoon dynamics and the interaction between monsoon and ENSO cycle [J]. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. (in Chinese), 27 (4): 484–502, doi:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.2003. 04.05.

Huang R H, Chen W, Yang B L, et al. 2004. Recent advances in studies of the interaction between the East Asian winter and summer monsoons and ENSO cycle [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 21 (3): 407–424, doi:10.1007/ BF02915568.

Huang R H, Chen J L, Huang G. 2007. Characteristics and variations of the East Asian monsoon system and its impacts on climate disasters in China [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 24: 993–1023, doi:10.1007/s00376-007-0993-x.

Jin F F, An S I, Timmermann A, et al. 2003. Strong El Niño events and nonlinear dynamical heating [J]. Geophys. Res. Lett., 30 (3): 1120, doi: 10.1029/2002GL016356.

Kang I S, Kug J S. 2002. El Niño and La Niña sea surface temperature anomalies: Asymmetry characteristics associated with their wind stress anomalies [J]. J. Geophys. Res., 107 (19): 4372, doi: 10.1029/ 2001JD000393.

Rayner N A, Parker D E, Horton E B, et al. 2003. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century [J]. J. Geophys. Res., 108 (D14): 4407, doi:10.1029/2002JD002670 .

Sun Bomin, Sun Shuqing. 1994. The analysis on the features of the atmospheric circulation in preceding winters for the summer drought and flooding in the Yangtze and Huaihe River valley [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 11 (1): 79–90, doi:10.1007/BF02656997.

Tao Shiyan, Chen Longxun. 1987. A review of recent research on the East Asian summer monsoon in China [M]// Chang C P, Krishnamurti T N. Monsoon Meteorology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 60–92.

Uppala S M, Kållberg P W, Simmons A J, et al. 2005. The ERA-40 re-analysis [J]. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 131 (612): 2961–3012, doi:10.1256/qj.04.176.

Wang B, Fan Z. 1999. Choice of South Asian summer monsoon indices [J]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 80 (4): 629–638, doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1999) 080<0629:COSASM>2.0.CO;2.

Wang B, Wu R G, Fu X H. 2000. Pacific–East Asian teleconnection: How does ENSO affect East Asian climate? [J]. J. Climate, 13 (9): 1517–1536, doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2000)013<1517:PEATHD>2.0.CO;2.

Wang B, Zhang Q. 2002. Pacific–East Asian teleconnection. Part II: How the Philippine Sea anomalous anticyclone is established during El Niño development [J]. J. Climate, 15 (22): 3252–3265, doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2002)015<3252:PEATPI>2.0.CO;2.

Wang L, Wu R G. 2012. In-phase transition from the winter monsoon to the summer monsoon over East Asia: Role of the Indian Ocean [J]. J. Geophys. Res., 117 (D11): D11112, doi:10.1029/2012JD017509.

Wu Aiming, Ni Yunqi. 1997. The influence of Tibetan Plateau on the interannual variability of Asian monsoon [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 14 (4): 491–504, doi:10.1007/s00376-997-0067-0.

Wu B, Li T, Zhou T J. 2010. Asymmetry of atmospheric circulation anomalies over the western North Pacific between El Niño and La Niña [J]. J. Climate, 23 (18): 4807–4822, doi:10.1175/2010JCLI3222.1.

吴国雄, 孟文. 1998. 赤道印度洋—太平洋地区海气系统的齿轮式耦合和ENSO事件 [J]. 大气科学, 22 (4): 470–480. Wu Guoxiong, Meng Wen. 1998. Gearing between the Indo-monsoon circulation and Pacific-Walker circulation and the ENSO. Part I: Data analysis [J]. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. (in Chinese), 22 (4): 470–480, doi:10.3878/j.issn. 1006-9895.1998.04.09.

Xie S P, Hu K M, Hafner J, et al. 2009. Indian Ocean capacitor effect on Indo–western Pacific climate during the summer following El Niño [J]. J. Climate, 22 (3): 730–747, doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2544.1.

Yang S, Lau K M, Kim K M. 2002. Variations of the East Asian jet stream and Asian–Pacific–American winter climate anomalies [J]. J. Climate, 15 (3): 306–325, doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2002)015<0306:VOTEAJ>2.0.CO; 2.

Zhang R H, Sumi A, Kimoto M. 1996. Impact of El Niño on the East Asian monsoon: A diagnostic study of the ’86/87 and ’91/92 events [J]. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 74: 49–62.

Zhang R H, Sumi A, Kimoto M. 1999. A diagnostic study of the impact of El Niño on the precipitation in China [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 16 (2): 229–241, doi:10.1007/BF02973084.

Zhang R H, Li T R, Wen M, et al. 2015. Role of intraseasonal oscillation in asymmetric impacts of El Niño and La Niña on the rainfall over southern China in boreal winter [J]. Climate Dyn., 45 (3–4): 559–567, doi:10.1007/s00382-014-2207-4.

Zhou W, Chan J C L, Li C Y. 2005. South China Sea summer monsoon onset in relation to the off-equatorial ITCZ [J]. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 22 (5): 665–676, doi:10.1007/BF02918710.

祝从文,何金海,吴国雄. 2000. 东亚季风指数及其与大尺度热力环流年际变化关系 [J]. 气象学报, 58 (4): 391–402. Zhu C W, He J H, Wu G X. 2000. East Asian monsoon index and its interannual relationship with largescale thermal dynamic circulation [J]. Acta Meteor. Sinica (in Chinese), 58(4): 391–402,doi:10.11676/qxxb2000.042.

项目资助 国家自然科学基金项目41230527、41461144001

Funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 41230527, 41461144001)

文章编号1006-9895(2016)04-0831-10中图分类号 P461

文献标识码A

doi:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.1509.15192

收稿日期2015-05-05;网络预出版日期 2015-09-15

作者简介徐霈强,男,1992年出生,硕士研究生,主要从事东亚季风变异和海气相互作用方面的研究。E-mail: peiqiang@mail.iap.ac.cn

通讯作者冯娟,E-mail: juanfeng@mail.iap.ac.cn

Asymmetric Role of ENSO in the Link between the East Asian Winter Monsoon and the Following Summer Monsoon

XU Peiqiang1, 2, FENG Juan1, and CHEN Wen1

1 Center for Monsoon System Research, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190

2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049

AbstractEvidence demonstrates a link exists between the East Asian winter monsoon (EAWM) and the following East Asian summer monsoon (EASM). Previous studies have found that the EAWM and the following EASM are only closely linked in ENSO years. However, all these studies are based on the hypothesis that the atmosphere’s response to ENSO is symmetric. In fact, we demonstrate ENSO plays an asymmetric role in the EAWM–EASM link. This study divides the variability of the EAWM into an ENSO-related part (EAWMEN) and ENSO-unrelated part (EAWMRES). The results demonstrate that during strong EAWMENconditions (i.e., La Niña events), an anomalous cyclone persists from winter to summer over the western North Pacific (WNP), which can cause a weak EASM in the following summer. In contrast, during weak EAWMENconditions (i.e., El Niño events), an anomalous anticyclone persisting from winter to summer is observed over the WNP. However, the anomalous anticyclone’s intensity is much stronger than the counterpart and is located more southward. As a result, the intensity of EASM anomalies is stronger during weak EAWMENyears. This asymmetry may be attributed to the different evolutions of the SST anomalies over the tropical Pacific Ocean and the North Indian Ocean. During strong EAWMENconditions, the SST anomalies in the tropical central–eastern Pacific decay slowly and thus significant signals still persist in the following summer, which contribute to the persistence of the WNP anomalous cyclone in the following summer. However, during weak EAWMENconditions, the SST anomalies decay quickly in the tropical Pacific, while the Indian Ocean warms significantly in the following summer. Thus the anomalous anticyclone in the WNP results from the significantly warmed Indian Ocean through the “capacitor mechanism”.

KeywordsEast Asian summer monsoon, East Asian winter monsoon, ENSO, Asymmetry