青藏高原高寒草地优势禾草-紫花针茅内生真菌分离和鉴定

2016-04-27鲍根生李春杰

鲍根生,李春杰

(1.草地农业生态系统国家重点实验室,兰州大学草地农业科技学院,甘肃 兰州 730020;2.青海大学畜牧兽医科学院,青海 西宁 810016)

青藏高原高寒草地优势禾草-紫花针茅内生真菌分离和鉴定

鲍根生1,2,李春杰1*

(1.草地农业生态系统国家重点实验室,兰州大学草地农业科技学院,甘肃 兰州 730020;2.青海大学畜牧兽医科学院,青海 西宁 810016)

摘要:紫花针茅作为青藏高原高寒草原群落中主要优势禾草之一,关于该植物所感染禾草内生真菌的形态和分类研究尚未见报道。本研究采用分离培养获取不同样点的紫花针茅内生真菌菌落,利用特异性引物克隆紫花针茅内生真菌序列,并与Genbank中下载的序列共同构建系统进化树。结果表明,青海省紫花针茅样品带菌率高达100%,而其他区域样品均不带菌。分离的内生真菌菌落从菌落形态、生长速度及分生孢子形态等特征均与Epichloё属内生真菌的形态特征相似。系统进化关系表明,它们分别与北美洲竖针茅体内无性态内生真菌Epichloё chisosa、醉马草内生真菌Epichloё inebrians及甘肃内生真菌Epichloё gansuensis具有较近的亲缘关系,进一步说明紫花针茅所感染内生真菌与宿主间未体现出严格的宿主特异性。

关键词:青藏高原;紫花针茅;内生真菌;系统发育;宿主

紫花针茅(Stipapurpurea)隶属禾本科针茅属[1],多年生草本,系寒旱生植物,粗蛋白含量高,粗纤维少,营养价值比较高[2-3]。主要分布在海拔1900~5150 m的高原地带,是青藏高原、帕米尔高原和中亚高山地带的特有植物[4-5]。紫花针茅草原是青藏高原地区高寒草地中分布面积较广、最具有代表性的草地类型,其面积占高寒草原类草地总面积的30.92%[6-7];其建群种紫花针茅具有耐寒、耐旱、耐践踏和抗风沙等特性[8-10]。

目前有关紫花针茅研究主要集中在基因多样性、群落分类、生理生态和草原群落等方面[3,5-6,9,11-16]。然而,有关紫花针茅感染的微生物及与微生物间互作研究较少,李振东等[17]分离紫花针茅体内内生细菌,发现内生细菌具有较强的抑菌活性。南志标和李春杰[18]研究发现,紫花针茅带菌高达67%;同时,笔者在青海高原禾草内生真菌带菌率检测研究发现,紫花针茅带菌率高达100%(数据未发表)。

麦角菌科的内生真菌与冷季型禾草在长期进化过程中形成了互惠共生关系[19-23]。内生真菌不仅能提高宿主对逆境的适应性[24-29],同时合成的次生代谢物能提高草食家畜和昆虫的拒食性[30-34];而宿主为内生真菌提供生活的场所和生长所需的营养物质[20,35-36]。Leuchtmann等[37]将Neotyphodium属内生真菌归类到Epichloё属,总计43种禾草内生真菌。目前,分子系统发育分析已广泛应用于禾草内生真菌分类和系统进化研究中,其中保守区的编码蛋白(tubB)、转录延长因子(tefA)和肌动蛋白(actG)基因序列被用来区分不同宿主体内内生真菌的分类[38-39]。本研究利用形态学和分子标记的方法,通过菌落和分生孢子形态比较,构建系统发育树,对紫花针茅内生真菌进行归类并进行分子鉴定,为今后紫花针茅在高寒逆境条件下适应性和利用内生真菌抗逆性育种提供新思路。

1材料与方法

1.1供试材料

紫花针茅植物样品主要在青藏高原地区天然高寒草地上采集,于2012年至2014年8-9月在牧草成熟季节,在西藏阿里地区、青海省、四川省西北部和甘肃省南部采集紫花针茅单株样品22份。采集区域介于北纬30°14′54.0″-37°19′50.2″,东经79°55′47″-102°32′42″,草地类型主要以高寒草原为主(表1)。每个采样点间隔10 m,随机采集10~20株紫花针茅单株地上部分放入信封,编号后带回实验室。

1.2内生真菌分离和培养

每个单株挑选5粒种子,参照李春杰等[39]的方法进行种皮和糊粉层内生真菌检测,具体方法参照Iannone等[40]的方法。选取带菌种子进行表面消毒,具体方法为:先用70%酒精消毒1 min,然后用1%次氯酸钠消毒3~5 min,用无菌水冲洗3~5次,用灭菌滤纸吸干种子表面残留的液体,随后将种子摆放到马铃薯葡萄糖琼脂(PDA)培养基上,在25℃黑暗条件下培养1月。在种子表面形成菌落后,在边缘挑取少许菌丝在PDA培养基上进行培养,待产孢后挑取单个孢子在25℃黑暗条件下进行纯培养,每周测量菌落直径,4周后进行分生孢子和分生孢子梗形态观察和大小测量。

1.3DNA分离、扩增和纯化

参照高效真菌DNA提取试剂盒(OMEGA公司)提取DNA方法, 用单孢培养菌落的10~50 mg 新鲜的紫花针茅内生真菌菌丝提取内生真菌全基因组,分别用tubB(5′-GAGAAAATGCGTGAGATTGT,3′-GTTTCGTCCGAGTTCTCGAC),tefA(5′-GGGTAAGGACGAAAAGACTCA,3′-CGGCAGCGATAATCAGGATAG)和actG(5′-GAAGTTGCTGCCCTCGTTATC,3′-AACCACCGATCCAGACAGAGT) 3对引物对内生真菌基因组进行聚合酶链式反应(PCR)扩增。PCR选用25 μL体系,包括5 ng DNA模板、1.0 U Taq DNA聚合酶、1×PCR缓冲液、1.5 mmol/L MgCl2、0.2 mmol/L dNTP (dATP、dCTP、dGTP、dTTP)和1 μmol/L上、下游引物。PCR循环参数设定为:94℃预变性5 min,94℃变性30 s,50℃退火1 min,35个循环,最后,72℃延展10 min,并在4℃保持。将PCR扩增产物在1.5%琼脂糖凝胶上进行电泳,回收片段连接于pGEM®-T Easy载体(Promega生物公司)并转入大肠杆菌DH5α。每个样本挑选5个阳性克隆,并送交兰州励合生物技术公司进行测序。所测序列提交至GenBank数据库,tubB序列登录号为KP877323~KP877330,tefA序列登录号为KP877315~KP877322,actG序列登录号为KP877331~KP877338(表1)。

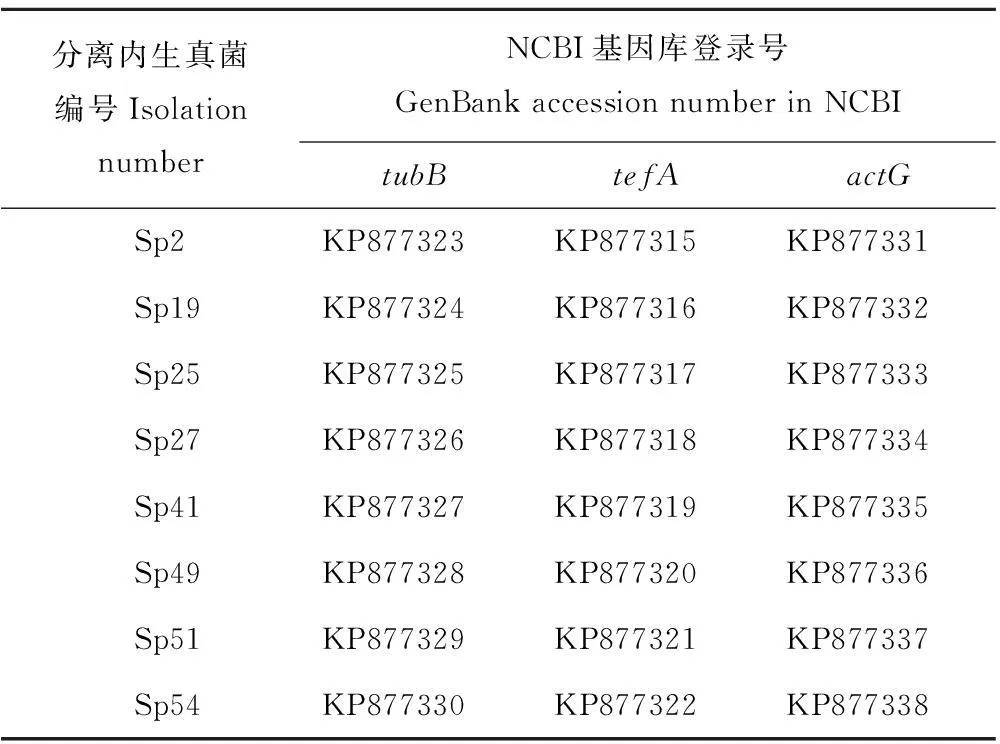

表1 紫花针茅分离内生真菌编号和美国生物技术信息

1.4序列比对及系统发育分析

用紫花针茅内生真菌tubB、tefA和actG测序序列在NCBI基因数据库中Blast程序搜索直系同源序列,挑选禾草内生真菌相关的tubB、tefA和actG序列(表2)。由于NCBI提交的不同内生真菌不同标记序列长度存在差异,根据Craven等[38]和Gentile等[41]提出tubB、tefA和actG序列差异主要体现在内含子区域差异的观点,所以所用序列去除外显子而保存内含子进行系统发育分析[37,40]。用Clustal X进行比对,比对结果中有歧义的位点进行人工优化。比对结果采用PAUP*4.0b10软件中最大简约法(maximun parsimony,MP)构建系统发育树。空白位点作为缺失信息处理,同时,每个位点状态不排序且权重相等。采用启发式搜索获取最大简约树,用Bootstrap自展法1000次重复,并将自展值大于50值标记到进化树分枝上。

2结果与分析

2.1紫花针茅内生真菌分离和形态特征

2012-2014年分别从青藏高原地区22个样点采集紫花针茅植物样品,其中青海省11个样点采集紫花针茅带菌率高达100%,而西藏阿里、日喀则、那曲地区9个样点紫花针茅不带菌,四川省和甘肃省2个样点紫花针茅亦不带菌(表2)。青海省紫花针茅分布样点共分离获得8个菌株,分离菌株的菌落形态相似。在25℃黑暗培养条件下,PDA培养基上生长缓慢,平均生长速率为11~15 mm/周;菌落正面白色棉质,质地致密,气生菌丝发达,菌落中央隆起,边缘整齐(图1B);反面从中央到边缘由暗褐色变成黄色(图1C)。分生孢子单生于分生孢子梗顶端,光滑、透明、无隔,舟形或肾形,(3.2~7.3) μm×(2.6~3.3) μm(图1E);分生孢子梗基部单生或基部生成两个分枝,长8.4~28.0 μm,基部宽1.5~2.9 μm,顶端宽0.6~1.1 μm(图1D~E)。以上特征均符合Epichloё属内生真菌的形态特征。

2.2系统发育分析

将紫花针茅分离的8个菌株(stpu2、stpu19、stpu25、stpu27、stpu41、stpu49、stpu51、stpu54)的总DNA为模板,利用tubB、tefA和actG3个管家基因为引物分别扩增目的片段基因,各个引物只扩增到一个目的片段,未发现其他拷贝。通过NCBI比对后,分别抽取54, 52, 53条禾草内生真菌tubB、tefA和actG序列; 构建tubB系统

表2 紫花针茅采集样点及内生真菌带菌率检测

发育树的序列比对后长度为522 bp, 其中包含156个保守位点、297个变异位点和192个简约位点;构建tefA系统发育树的序列比对后长度为495 bp,包含166个保守位点、325个变异位点和166个简约位点;构建actG系统发育树的序列比对后长度为512 bp,包含292个保守位点、335个变异位点和204个简约位点。

图1 紫花针茅内生真菌菌丝、PDA菌落形态、分生孢子梗和分生孢子结构 Fig.1 Photographs of hyphae, colony and conidial morphology isolated endophytes from S. purpurea A:种皮内内生菌丝形态; B~C:菌落正反面形态; D~E:分生孢子和分生孢子梗形态;菌落大小标尺长度为 10 mm, 分生孢子和分生孢子梗大小标尺长度为20 μm。A: Fungal hyphae within seed coat; B-C: Morphology of upper and reverse of colony; D-E: Size and morphologies of conidial; Scale bar for colony pictures is 10 mm, and for conidia pictures, 20 μm.

tubB序列构建的系统发育树显示,紫花针茅分离的8个菌株与Epichloёgansuensis和E.chisosa非常接近(图2a)。其中,stpu2、stpu19、stpu27和stpu41与分离于北美洲的竖针茅(Achnatherumeminens)体内无性态内生真菌E.chisosa聚到一起,自展值分别高达100%和84%,形成两个明显亚枝;而stpu25、stpu49、stpu51和stpu54与分离于我国醉马草(Achnatheruminebrians)内生真菌E.inebrians聚到一起,同时还与北美洲的毛边臭草(Melicaciliata)感染的E.guerinii、内蒙古羽茅(Achnatherumsibiricum)感染的E.sibiricum和醉马草(A.inebrians)感染的E.gansuensis共同形成一个分支,自展值达到64%。

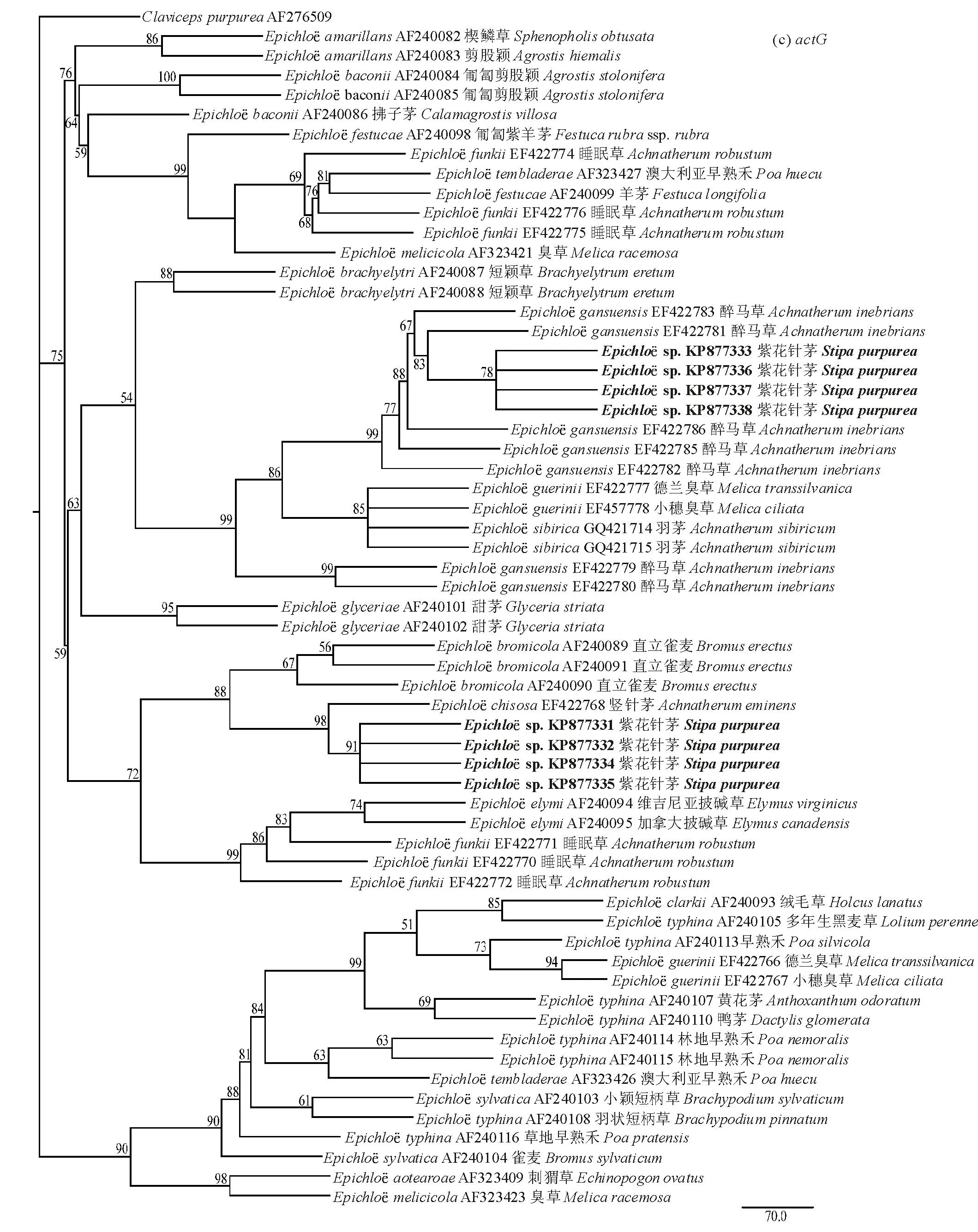

图2 紫花针茅stpu内生真菌系统进化最大简约树Fig.2 Phylogenetic trees of Epichloё sp. based on maximum parsimony (MP) analysis of sequences from intron portions (a) tubB:树长522 each of 522 steps,一致性指数Consistency index (CI)=0.7605;保留指数Retention index (RI)=0.8957;复定一致性指数Rescaled consistency index (RC)=0.6812;(b) tefA:树长=495 each of 495 steps,CI=0.820,RI=0.926,RC=0.759;(c)actG:树长=512 each of 512 steps,CI=0.883,RI=0.935,RC=0.825。将Claviceps purpurea (AF276506、AF276508和AF276509)作为外群;进化树上只显示自展值大于50%的节点值。The Claviceps purpurea (AF276506, AF276508, AF276509) was designated as the outgroup for rooting trees. Numbers associated with branches were bootstrap support percentages (≥50%) assessed with 1000 replications.

续图2 紫花针茅stpu内生真菌系统进化最大简约树Continued Fig.2 Phylogenetic trees of Epichloё sp. based on maximum parsimony (MP) analysis of sequences from intron portions

续图2 紫花针茅stpu内生真菌系统进化最大简约树Continued Fig.2 Phylogenetic trees of Epichloё sp. based on maximum parsimony (MP) analysis of sequences from intron portions

tefA序列构建的系统发育树拓扑结构与tubB相似(图2b),其中,sp2、sp19与竖针茅感染的E.chisosa、北美洲的类雀麦(Bromusramosus)和直立雀麦(Bromuserectus)感染的E.bromicola、硬直黑麦草(Loliumrigidum)感染的E.occultans、短颖草(Brachyelytrumeretum)感染的E.brachyelytri聚到一支;而sp27、sp41与竖针茅感染的E.chisosa和草地早熟禾(Poapratensis)感染的E.typhina单独形成另外一个亚枝。其他4个菌株与醉马草感染的E.gansuensis单独形成一支,自展值高达86%。

与tubB和tefA系统发育树不同,紫花针茅actG拓扑结构只形成两个明显分支(图2c),其中stpu2、stpu19、stpu27、stpu41与竖针茅感染的E.chisosa形成单一分支,自展值高达91%;而其他4个菌株与醉马草感染的E.gansuensis形成另外一个分支,自展值达到78%。

3讨论

针茅族隶属禾本科早熟禾亚科,目前全球约有600种,主要分布在亚欧大陆、美洲和澳大利亚等地,成为温性草原群落中的主要建群禾草之一[42]。近年来,随着学者们对禾草内生真菌共生体研究的日益关注,通过内生真菌检测和分离技术,先后从北美洲的竖针茅和睡眠草(Achnatherumrobustum)中分别分离到Epichloёchisosa和E.funkii[43-44],中国醉马草中分离到E.gansuensis和E.inebrians[45-46],中国内蒙古地区羽茅中分离到E.siegelii[47-48],总共5种Epichloё属内生真菌。这些内生真菌在菌落生长速度和分生孢子形态上均表现出差异。例如,菌落生长速度以竖针茅分离的内生真菌最慢,而臭草(Melicaracemosa)和睡眠草内生真菌菌落生长速度最快,羽茅、紫花针茅和醉马草菌落生长速度居中;睡眠草内生真菌的分生孢子最大,而羽茅内生真菌孢子较小;睡眠草和羽茅内生真菌分生孢子梗最长,而醉马草内生真菌孢子梗最短[43-45,49]。可见,不同类型内生真菌菌落生长特性主要取决于不同内生真菌的基因型和营养条件差异[49-50]。同时,由于睡眠草感染的内生真菌是E.typhina和E.festucae杂交而来,基因组明显大于两个亲本,同时许多杂交形成的内生真菌在外部形态上也明显表现出比亲本菌落生长较快、分生孢子和分生孢子梗较大较长等特点[41,44,51]。

Moon等[44]研究发现,北美洲竖针茅感染的内生真菌E.chisosa是由北美洲E.amarillans、亚欧大陆的E.bromicola和E.typhina3种有性态内生真菌杂交形成,而睡眠草感染的内生真菌E.funkii是由北美洲E.elymi和E.festucae杂交形成。本研究中,紫花针茅所感染的内生真菌用tubB和tefA两种管家基因扩增序列与针茅族和其他Epichloё属内生真菌序列构建系统发育树,发现sp2、sp19和sp27、sp41分别与竖针茅分离内生真菌扩增所得不同拷贝基因序列形成明显两个分支,且与竖针茅杂交亲本E.typhina和E.bromicola形成较好的拓扑结构;而其他4个菌株所得序列与醉马草分离的E.gansuensis组成另外一个分支(图2b,c)。可见,紫花针茅感染的内生真菌与宿主间未呈现严格特异性,表明紫花针茅可能成为不同内生真菌的宿主潜力较高。这一现象在其他冷季型禾草分离不同类型内生真菌的研究结果中也得到证实,例如,Moon等[52]从南美洲刺猬草(Echinopogonovatus)体内分离出两种Epichloё内生真菌,其中从新西兰和澳大利亚分离出无性态(Neotyphodium)内生真菌,而从澳大利亚分离的内生真菌是由E.festucae和E.typhina杂交而成的有性态内生真菌(Epichloё)。同时,中国西部分布的醉马草感染的内生真菌也存在差异,虽然两种内生真菌均是无性态内生真菌,但在菌落、分生孢子形态和基因组组成等方面存在明显差异[45-46];Zhang等[53]研究也发现内蒙古草地主要优势禾草——羽茅同时感染E.sibiricum和E.gansuense两种内生真菌。另外,同一种Epichloё属内生真菌可能感染不同寄主的观点也从侧面证实上述的观点。例如,Craven等[38]针对E.typhina内生真菌和宿主范围进行分析,发现能从早熟禾亚科的黑麦草属(Lolium)、早熟禾属(Poa)、梯牧草属(Phleum)、短柄草属(Brachypodium)、黄花茅属(Anthoxanthum)、鸭茅属(Dactylis)和偃麦草属(Elytrigia)的10余种植物中分离到这种内生真菌;然而,相对于大多数有性态禾草内生真菌与宿主之间还是保持高度的特异性。主要原因可能: 1)紫花针茅内生真菌基因组保持较高的变异位点,可能导致紫花针茅内生真菌存在较高的基因多样性。根据Zhang等[53]研究结果,羽茅中分离的E.gansuensis较E.sibiricum具有更高的基因多样性,同时发现约13%内生真菌存在杂合体,揭示不同羽茅内生真菌种群间可能存在杂交现象。本研究中紫花针茅在tubB和tefA引物扩增时,出现3个不同分支,由于未开展基因多样性等有关的研究,所以关于其是否杂交而来还有待进一步证实; 2)内生真菌和宿主进化时间可能存在差异,即在宿主分化之前,内生真菌已经完成分化,最终造成同一宿主可能感染不同内生真菌[52],Hamasha等[54]研究表明青藏高原和约旦地区的紫花针茅个体基因组间存在较大差异,这与其他欧洲大陆针茅族物种保持相对较低的基因个体差异不一致[55];同时,Bieniek和Pokorny[56]根据针茅属植物颖果和花粉化石资料推算,针茅族地理起源的中心位于欧洲中部,并以欧洲中部为原点向周边大陆迁移,可以从侧面证实紫花针茅能与北美地区的竖针茅感染同种类型的内生真菌。3)一般无性态内生真菌是由不同的有性态内生真菌杂交形成而来[41,44,53,57-58],根据Zhang等[53]对中国内蒙古地区羽茅感染内生真菌多样性分析,虽然羽茅中部分内生真菌存在杂交的潜力,但基因漂流被严重阻碍,主要以无性态内生真菌存在。本研究紫花针茅扩增时条带单一,可能与基因流严格抑制有关。

值得注意的是在构建actG系统发育树时, sp2、sp19、sp27和sp41与竖针茅单拷贝actG序列很好的组成一枝,而且与E.bromicola形成了较好的亲缘关系。而这与在tefA和tubB中形成明显的两个分支形成差异(图2),原因可能是引物扩增的位点出现分化,导致形成假阴性扩增,这一研究结果与Moon[44]对针茅族和臭草族内生真菌起源研究中得到的结论一致。

References:

[1]Liu S W. Flora of Qinghai[M]. Xining: Qinghai People Press, 1999.

[2]Shi Y, Ma Y L, Ma W H,etal. Large scale patterns of forage yield and quality across Chinese grasslands. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2013, 58(10): 1187-1199.

[3]Liu W S, Dong M, Song Z P,etal. Genetic diversity pattern ofStipapurpureapopulations in the hinterland of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Annals of Applied Biology, 2009, 154(1): 57-65.

[4]Qpist. Vegetation of Tibet[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1988

[5]Yang Y Q, Li X, Kong X X,etal. Transcriptome analysis reveals diversified adaptation ofStipapurpureaalong a drought gradient on the Tibetan Plateau. Functional & Integrative Genomics, 2014, 15(3): 295-307.

[6]Duan M J, Gao Q Z, Wan Y F,etal. Effect of grazing on community characteristics and species diversity ofStipapurpureaalpine grassland in North Tibet. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2010, 30(14): 3892-3900.

[7]Miller D J. The Tibetan Steppe. Grasslands of the World[M]. Rome: UN Food and Agriculture Organization, 2005.

[8]Hu M Y, Zhang L, Luo T X,etal. Variations in leaf functional traits ofStipapurpureaalong a rainfall gradient in Xizang, China. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2012, 36(2): 136-143.

[9]Yue P P, Lu X F, Ye R R,etal. Distribution ofStipapurpureasteppe in the Northeastern Qinghai-Xizang Plateau (China). Russian Journal of Ecology, 2011, 42(1): 50-56.

[10]Li X J, Zhang X Z, Wu J S,etal. Root biomass distribution in alpine ecosystems of the northern Tibetan Plateau. Environmental Earth Sciences, 2011, 64(7): 1911-1919.

[11]Yang S H, Li X, Yang Y Q,etal. Comparing the relationship between seed germination and temperature forStipaspecies on the Tibetan Plateau. Botany, 2014, 92(12): 895-900.

[12]Sun J, Peng M, Chen G C,etal. Study on community characteristics and community diversity inStipasteppe of Qinghai Lake region. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica, 2003, 23(11): 1963-1968.

[13]Han Y J, Chen G C, Zhou G Y,etal. Study on morphological response of the alpine steppes plant individuals to grazing stress. Journal of the Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2006, 23(1): 118-124.

[14]Wang W, Liang C Z, Liu Z L,etal. Analysis of the plant individual behavior during the degradation and restoring succession in steppe community. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology, 2000, 24(3): 268-274.

[15]Zhu J T, Jiang L, Zhang Y J,etal. Below-ground competition drives the self-thinning process ofStipapurpureapopulations in northern Tibet. Journal of Vegetation Science, 2015, 26(1): 166-174.

[16]Yue P P, Peng M. On the research progress ofStipapurpureasteppe in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Yulin University, 2014, 24(4): 1-6.

[17]Li Z D, Chen X R, Li P. Screening and identification of endophytic bacteria fromStipapurpurea. Grassland and Turf, 2011, 31(1): 8-12.

[18]Nan Z B, Li C J. Roles of the grass-Neotyphodiumassociation in pastoral agriculture systems. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2004, 24(3): 605-616.

[19]Saikkonen K, Faeth S H, Helander M,etal. Fungal endophytes: a continuum of interactions with host plants. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 1998, 29: 319-343.

[20]Clay K, Schardl C L. Evolutionary origins and ecological consequences of endophyte symbiosis with grasses. The American Naturalist, 2002, 160(S4): S99-S127.

[21]Rodriguez R, White Jr J, Arnold A,etal. Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles. New Phytologist, 2009, 182(2): 314-330.

[22]Schardl C L. The Epichloae, symbionts of the grass subfamily Poöideae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 2010, 97(4): 646-665.

[23]Jin W J, Li C J, Wang Z F. Research advances on diversity of grassEpichloё endophytes. Acta Prataculturae Sinica, 2015, 24(1): 168-175.

[24]Kane K H. Effects of endophyte infection on drought stress tolerance ofLoliumperenneaccessions from the Mediterranean region. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 2011, 71(3): 337-344.

[25]Malinowski D P, Belesky D P. Adaptations of endophyte-infected cool-season grasses to environmental stresses: mechanisms of drought and mineral stress tolerance. Crop Science, 2000, 40(4): 923-940.

[26]Oberhofer M, Güsewell S, Leuchtmann A. Effects of natural hybrid and non-hybridEpichloё endophytes on the response ofHordelymuseuropaeusto drought stress. New Phytologist, 2014, 201(1): 242-253.

[27]Song M L, Li X Z, Saikkonen K,etal. An asexualEpichloё endophyte enhances waterlogging tolerance ofHordeumbrevisubulatum. Fungal Ecology, 2015, 13: 44-52.

[28]Song M L, Chai Q, Li X Z,etal. An asexualEpichloё endophyte modifies the nutrient stoichiometry of wild barley (Hordeumbrevisubulatum) under salt stress. Plant and Soil, 2014, 387(1): 1-13.

[29]Hall S L, Mcculley R L, Barney R J,etal. Does fungal endophyte infection improve tall fescue’s growth response to fire and water limitation. PloS One, 2014, 9(1): e86904.

[30]Omacini M, Chaneton E J, Ghersa C M,etal. Symbiotic fungal endophytes control insect host-parasite interaction webs. Nature, 2001, 409: 78-81.

[31]Nance A M. Studies on the Influence ofNeotyphodiumEndophytes, Below-ground Insect Herbivory and Environmental Stress on Performance of Tall Fescue and Kentucky Bluegrass[D]. Indiana: Purdue University, 2011.

[32]Zhang X X, Li C J, Nan Z B,etal.Neotyphodiumendophyte increasesAchnatheruminebrians(drunken horse grass) resistance to herbivores and seed predators. Weed Research, 2012, 52(1): 70-78.

[33]Shiba T, Arakawa A, Sugawara K. Effects of alkaloids from fungal endophytes in grass-Epichloё associations on survival of the sorghum plant bug (Stenotusrubrovittatus). Grassland Science, 2014, 61(1): 24-27.

[34]Alderman S C. Survival, germination, and growth ofEpichloё typhina and significance of leaf wounds and insects in infection of orchardgrass. Plant Disease, 2013, 97(3): 323-328.

[35]Dobrindt L, Stroh H G, Isselstein J,etal. Infected-not infected: factors influencing the abundance of the endophyteNeotyphodiumloliiin managed grasslands. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2013, 175: 54-59.

[37]Leuchtmann A, Bacon C W, Schardl C L,etal. Nomenclatural realignment ofNeotyphodiumspecies with genusEpichloё. Mycologia, 2014, 106(2): 202-215.

[38]Craven K, Hsiau P, Leuchtmann A,etal. Multigene phylogeny ofEpichloё species, fungal symbionts of grasses. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 2001, 88(1): 14-34.

[39]Li C J, Nan Z B, Liu Y,etal. Methodology of endophyte detection of drunken horse grass (Achnatheruminebrians). Edible Fungi of China, 2008, 27: 16-19.

[40]Iannone L J, Cabral D, Schardl C L,etal. Phylogenetic divergence, morphological and physiological differences distinguish a newNeotyphodiumendophyte species in the grassBromusauleticusfrom South America. Mycologia, 2009, 101(3): 340-351.

[41]Gentile A, Rossi M S, Cabral D,etal. Origin, divergence, and phylogeny ofEpichloё endophytes of native Argentine grasses. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2005, 35(1): 196-208.

[42]Hamasha H R, Von Hagen K B, Röser M.Stipa(Poaceae) and allies in the old world: molecular phylogenetics realigns genus circumscription and gives evidence on the origin of American and Australian lineages. Plant Systematics and Evolution, 2012, 298(2): 351-367.

[43]White Jr J, Morgan J G. Endophyte-host associations in forage grasses VII.Acremoniumchisosum, a new species isolated fromStipaeminensin Texas. Mycotaxon, 1987, 28(1): 179-189.

[44]Moon C D, Guillaumin J J, Ravel C,etal. NewNeotyphodiumendophyte species from the grass tribesStipeaeandMeliceae. Mycologia, 2007, 99(6): 895-905.

[45]Li C J, Nan Z B, Paul V H,etal. A newNeotyphodiumspecies symbiotic with drunken horse grass (Achnatheruminebrians) in China. Mycotaxon, 2004, 90(1): 141-147.

[46]Bruehl G W, Kaiser W J, Klein R E. An endophyte ofAchnatheruminebrians, an intoxicating grass of northwest China. Mycologia, 1994, 86(6): 773-776.

[47]Zhang X, Ren A Z, Wei Y K,etal. Taxonomy, diversity and origins of symbiotic endophytes ofAchnatherumsibiricumin the Inner Mongolia Steppe of China. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2009, 301(1): 12-20.

[48]Zhu M J, Ren A Z, Wen W,etal. Diversity and taxonomy of endophytes fromLeymuschinensisin the Inner Mongolia steppe of China. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2013, 340(2): 135-145.

[49]Li C J, Nan Z B, Li F. Biological and physiological characteristics ofNeotyphodiumgansuensesymbiotic withAchnatheruminebrians. Microbiological Research, 2008, 163(4): 431-440.

[50]Lukito Y. Investigation into the Role of PacC inEpichloёfestucaeDevelopment and Symbiosis with Perennial Ryegrass[D]. Palmerston North: Massey University, 2014.

[51]Fjellheim S, Rognli O A. Genetic diversity within and among NordicMeadowfescue(Huds.) cultivars determined on the basis of AFLP markers. Crop Science, 2005, 45(5): 2081-2086.

[52]Moon C D, Miles C O, Järlfors U,etal. The evolutionary origins of three newNeotyphodiumendophyte species from grasses indigenous to the Southern Hemisphere. Mycologia, 2002, 94(4): 694-711.

[53]Zhang X, Ren A Z, Ci H C,etal. Genetic diversity and structure ofNeotyphodiumspecies and their hostAchnatherumsibiricumin a natural grass-endophyte system. Microbial Ecology, 2010, 59(4): 744-756.

[54]Hamasha H, Schmidt L A, Durka W,etal. Bioclimatic regions influence genetic structure of four JordanianStipaspecies. Plant Biology, 2013, 15(5): 882-891.

[55]Durka W, Nossol C, Welk E,etal. Extreme genetic depauperation and differentiation of both populations and species in Eurasian feather grasses (Stipa). Plant Systematics and Evolution, 2013, 299(1): 259-269.

[57]Charlton N D, Craven K D, Afkhami M E,etal. Interspecific hybridization and bioactive alkaloid variation increases diversity in endophyticEpichloё species ofBromuslaevipes. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2014, 90(1): 276-289.

[58]Moon C D, Scott B, Schardl C L,etal. The evolutionary origins ofEpichloё endophytes from annual ryegrasses. Mycologia, 2000, 92(6): 1103-1118.

参考文献:

[1]刘尚武.青海植物志[M]. 西宁: 青海人民出版社, 1999.

[6]段敏杰, 高清竹, 万运帆, 等. 放牧对藏北紫花针茅高寒草原植物群落特征的影响. 生态学报, 2010, 30(14): 3892-3900.

[8]胡梦瑶, 张林, 罗天祥, 等. 西藏紫花针茅叶功能性状沿降水梯度的变化. 植物生态学报, 2012, 36(2): 136-143.

[12]孙菁, 彭敏, 陈桂琛, 等. 青海湖区针茅草原植物群落特征及群落多样性研究. 西北植物学报, 2003, 23(11): 1963-1968.

[13]韩友吉, 陈桂琛, 周国英, 等. 青海湖地区高寒草原植物个体特征对放牧的响应. 中国科学院研究生院学报, 2006, 23(1): 118-124.

[14]王炜, 梁存柱, 刘钟龄, 等. 草原群落退化与恢复演替中的植物个体行为分析. 植物生态学报, 2000, 24(3): 268-274.

[16]岳鹏鹏, 彭敏. 青藏高原紫花针茅草原研究进展. 榆林学院学报, 2014, 24(4): 1-6.

[17]李振东, 陈秀蓉, 李鹏. 紫花针茅内生细菌的分离与鉴定. 草原与草坪, 2011, 31(1): 8-12.

[18]南志标, 李春杰. 禾草—内生真菌共生体在草地农业系统中的作用. 生态学报, 2004, 24(3): 605-616.

[23]金文进, 李春杰, 王正凤. 禾草内生真菌的多样性及意义. 草业学报, 2015, 24(1): 168-175.

[39]李春杰, 南志标, 刘勇, 等. 醉马草内生真菌检测方法的研究. 中国食用菌, 2008, 27: 16-19.

Isolation and identification of endophytes infectingStipapurpurea, a dominant grass in meadows of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

BAO Gen-Sheng1,2, LI Chun-Jie1*

1.StateKeyLaboratoryofGrasslandAgro-ecosystems,CollegeofPastoralAgricultureScienceandTechnology,LanzhouUniversity,Lanzhou730020,China; 2.AcademyofAnimalScienceandVeterinaryMedicine,QinghaiUniversity,Xining810016,China

Abstract:Stipa purpurea is a dominant grass species in alpine grassland of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Research on this species to date has focused on defining genetic diversity, community classification, ecological function, physiological traits and grassland community characteristics; however, isolation and identification of endophyte fungi from S. purpurea has seldom been attempted. Endophyte was isolated from S. purpurea by leaf surface sterilization and axenic culture, and hyphae, colony physical characteristics, and conidial morphology were observed. Endophyte nucleotide sequences were cloned by tubB, tefA, and actG specific primers, and representative endophyte sequences were downloaded from Genbank to determine homology. A maximum likelihood method was applied to construct a phylogenetic tree. It was found that endophyte occurrence in S. purpurea was relatively high in Qinghai province, compared to other sites. Colony morphology characteristics, growth speed and morphology of conidia were identical to those of Epichloё spp. The results of tubB and tefA phylogeny indicated that four endophyte strains isolated from S. purpurea were most closely related to Epichloё chisosa from North American Achnatherum eminens and formed two distinct branches. Four other endophyte strains isolated from S. purpurea were most closely related to Epichloё indbrians and Epichloё gansuensis, which infect Achnatherum inebrians and these strains formed another distinct branch. In addition, analysis of actG phylogeny indicated that four clarify further endophyte strains isolated from S. purpurea were also most closely related to Epichloё chisosa from North American A. eminens and formed another distinct branch. Other endophyte strains isolated were most closely related to Epichloё gansuensis from China (Xinjiang) and formed another distinct branch. Our results suggest that the host-specificity might not occur in endophytes infecting S. purpurea and S. purpurea appears to be infected by various Epichloё species.

Key words:Qinghai-Tibet Plateau; Stipa purpurea; Epichloё; phylogeny; host

*通信作者

Corresponding author. E-mail:chunjie@lzu.edu.cn

作者简介:鲍根生(1980-),男,青海乐都人,助理研究员,在读博士。E-mail:baogensheng2008@hotmail.com

基金项目:国家973计划课题(2014CB138702),国家自然科学基金项目(31372366), 教育部创新团队发展计划项目(IRT13019)和公益性行业(农业)科研专项经费项目(201203041)资助。

收稿日期:2015-04-23;改回日期:2015-07-17

DOI:10.11686/cyxb2015214

http://cyxb.lzu.edu.cn

鲍根生,李春杰. 青藏高原高寒草地优势禾草-紫花针茅内生真菌分离和鉴定. 草业学报, 2016, 25(3): 32-42.

BAO Gen-Sheng, LI Chun-Jie. Isolation and identification of endophytes infectingStipapurpurea, a dominant grass in meadows of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta Prataculturae Sinica, 2016, 25(3): 32-42.