论近世琉球的历史和法律地位

——兼议钓鱼岛主权归属

2016-04-01刘丹

刘 丹

论近世琉球的历史和法律地位

——兼议钓鱼岛主权归属

刘 丹*

中日钓鱼岛争端中,日方极力撇开《马关条约》和其取得钓鱼岛所谓“主权”之间的关联,并认为钓鱼岛列屿的行政编制隶属琉球、琉球是日本的领土,所以钓鱼岛的主权应归日本,即日方主张包含着“钓鱼岛属于琉球、琉球属于日本,所以钓鱼岛属于日本”的荒谬逻辑。本文着重对琉球地位问题“去伪”,即通过探究近世琉球(1609-1879)在历史和国际法上的地位、中琉历史上的海上自然疆界,从而进一步印证钓鱼岛属于中国,为我国钓鱼岛主权主张提供有力论据。

琉球地位 国际法 钓鱼岛争端

2012年日本政府“购岛”闹剧后,中日钓鱼岛①我国称钓鱼岛为“钓鱼岛列屿”、“钓鱼台”等,日本称“尖阁列岛”。如无特殊说明,本文用“钓鱼岛”或“钓鱼岛列屿”指代钓鱼岛及其附属岛屿。争端使两国的对立状态持续发酵,至今仍僵持不下。我国学界尤其是大陆的相关研究中,对日本钓鱼岛“主权主张”中琉球因素的关注相对较少;由钓鱼岛争端引发的“琉球热”②近年来,我国民间对琉球主权的关切越来越高,网络上还出现了“还我琉球”的声音,学术界如徐勇、唐淳风等人也发表了“琉球地位未定”的观点。其实“琉球地位未定论”早期见于台湾,2012年左右才开始在大陆舆论中凸显,进而引发日本和冲绳舆论界的关注。日本政府“国有化”钓鱼岛并导致中日关系紧张化后,2012年5月8日,《人民日报》刊登学者张海鹏、李国强署名文章《论马关条约与钓鱼岛问题》,文末提出“历史上悬而未决的琉球问题也到了可以再议的时候”。就中国政府对琉球的立场,我国外交部发言人作出回应:“中国政府在有关问题上的立场没有变化。冲绳和琉球的历史是学术界长期关注的一个问题。该问题近来再度突出,背景是日方在钓鱼岛问题上不断采取挑衅行动,侵犯中国领土主权。学者的署名文章反映了中国民众和学术界对钓鱼岛及相关历史问题的关注和研究”。是在2012年因“购岛事件”导致中日关系紧张期间凸显出来。钓鱼岛主权问题和琉球地位问题盘根错节,对琉球地位问题,即“琉球主权是否属于日本”这个命题“去伪”,除了从历史、地理和国际法加强论证我国钓鱼岛主权主张外,如再对日本结合琉球和钓鱼岛隶属关系的相关主张③日本外务省:《关于“尖阁诸岛”所有权问题的基本见解(中译本)》,下载于http:// www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/senkaku/senkaku.html,2016年10月8日;日本外务省:《“尖阁诸岛”问答(中译本)》,下载于http://www.cn.emb-japan.go.jp/territory/ senkaku/question-and-answer.html,2016年10月8日。进行有理、有力、有据的驳斥,将起到“以子之矛,攻子之盾”的效果。

一、琉球的历史及中日琉三角关系

琉球是有着悠久历史文化传统的古老王国。琉球王国曾以东北亚和东南亚贸易的中转站而著称,贸易发达,有“万国之津梁”的美誉,其疆界的地理范围也和现在的日本冲绳县存在较大差别。然而,随着时间的推移,历史上琉球和中国的朝贡册封关系并不为现代人所熟知。1879年日本明治政府正式吞并琉球之前,琉球是有着独特历史的王国。琉球历史分为“先史时代”、“古琉球”和“近世琉球”三个时代。“先史时代”包括12世纪以前的旧石器时代和贝冢时代;“古琉球”是指从12世纪初到萨摩藩④萨摩藩:日本明治政府“废藩置县”前统治九州岛南部的地方政权,其势力范围涉及古代日本的律令制国家萨摩国(现鹿儿岛县西部)、大隅国(现鹿儿岛县东部和大隅诸岛)和日向国诸县郡(现宫崎县西南部)等地区。江户时代(1603-1868)的“幕藩体制”建立后,该政权遂成为萨摩藩,明治维新后正式命名为鹿儿岛藩。参见藤井贞文、林陆郎:《藩史事典》,东京:秋田书店1976年版,第342页,转引自袁家冬:《日本萨摩藩入侵琉球与东亚地缘政治格局变迁》,载于《中国社会科学》2013年第8期,第189页。藩主岛津氏入侵琉球的1609年,约500年的时间;“近世琉球”则从1609年萨摩入侵琉球岛,到1879年日本明治政府宣布琉球废藩置县为止,历时270年。⑤何慈毅:《明清时期琉球日本关系史》,南京:江苏古籍出版社2002年版,第3~5页。

(一)琉球王国历史及中琉宗藩关系

自1429年琉球统一到1879年琉球王国被日本吞并,琉球王国横跨了“古琉球”和“近世琉球”两个时代。自琉球按司察度于明朝洪武五年(1372年)向明朝皇帝朝贡,受册封为中山王,至清光绪五年(1879)年琉球被日本吞并、改为冲绳县为止,中国在明清两代和琉球保持了五百多年的封贡关系,中国遣册封使共24次,⑥对于清代册封琉球的次数,中日学者不存在争议,一般认为清册封琉球8次,册封使16名。但是对于明清两代中国册封琉球的总次数,历史学界的看法各异,一般认为是24次,但也有23次的说法,主要原因是对明朝册封次数,学界有不同看法。谢必震、武尚清和赤岭诚纪一致认为明朝册封琉球15次,册使27人;方宝川则认为明朝册封琉球14次,册封使26人。有的学者以中央政府是否在琉球本地为琉球国王进行册封仪式作为标准,没有把杨载出使琉球统计在列,从该角度看,明清两代共为琉球国王举行的册封典礼是23次而不是24次。参见谢必震、胡新:《中琉关系史料与研究》,北京:海洋出版社2010年版,第125~126页;徐斌:《明清士大夫与琉球》,北京:海洋出版社2011年,第83页。琉球来贡者则更多。⑦《明太祖实录》卷七十一记载,当年明太祖洪武帝遣杨载携带诏谕中山王的诏书中写到:“惟尔琉球,在中国东南,远处海外,未及报知,兹特遣使往谕,尔其知之。”参见《明太祖实录》卷七十一,洪武五年春正月甲子条。中琉建立外交关系后,凡是琉球国王病故,其世子承袭王位,必须经过明清两朝皇帝册封,才能正式对外称王。⑧徐斌:《明清士大夫与琉球》,北京:海洋出版社2011年版,第36页。我国有关钓鱼岛列屿的记载,多见于明清两代册封使归国回朝复命的“述职报告”即册封使录中。

(二)中日琉多边关系下的琉球“两属”问题

自1609年(明朝万历三十七年,日本江户幕府庆长十四年)萨摩藩攻破琉球,直到1879年明治政府在琉球废藩置县,这段时期被史学家称为琉球的“两属”时期。1609年,日本萨摩藩的岛津氏发兵入侵琉球,掳走国王尚宁和主要大臣,史称“庆长琉球之役”。此后,琉球“明属中国、暗属日本”⑨郑海麟:《钓鱼岛列屿之历史与法理研究(增订本)》,香港:明报出版社有限公司2011年版,第124页。的状态一直持续到日本明治维新初年。入清后,琉球进入第二尚氏王朝后期,琉球请求清政府予以册封。世子尚丰分别于天启五年(1625年)、天启六年(1626年)和七年(1627年)上表,请求中国给予册封。琉球天启年间的请封是在前述“庆长琉球之役”后,王国受到萨摩暗中掌控下进行的。⑩徐斌:《明清士大夫与琉球》,北京:海洋出版社2011年版,第4页。“庆长琉球之役”后,崇祯六年(1633年),在萨摩藩的不断催促下,琉球恢复和中国的封贡关系、恢复随贡互市。1872年9月,明治天皇下诏将琉球王室“升为琉球藩王,叙列华族”,①米庆余:《琉球历史研究》,天津:天津人民出版社1998年版,第112~114页。为吞并琉球做好了形式上的准备,1879年正式吞并琉球,这就是琉球为中日“两属”的由来。

萨摩藩入侵琉球后便从政治、经济等方面控制琉球。但为维持中琉朝贡贸易并从中牟利,就萨琉关系,萨摩藩全面贯彻了对中国的隐瞒策略,具体包括:1.不准琉球改行日本制度及日本名姓,以免为中国天使(册封使)所发现。例如,《纪考》称,“宽永元年”(天启四年,1624年)八月二十日,国相(萨摩藩对内自称“国”)承旨,命于琉球,自后官秩刑罚,宜王自制,勿称倭名,为倭服制。②杨仲揆:《琉球古今谈——兼论钓鱼台问题》,台北:台湾商务印书馆1990年版,第64~65页。2.册封使驻琉球期间,萨摩藩为欺瞒耳目所安排的措施为:所有日本官员如在番奉行、大和横目以及部署,非妥善伪装混入册封者,一律迁居琉球东海岸偏僻之地,以远离中国人活动之西海岸;又如,取缔一切日文招贴、招牌;再如,一切典籍、记录、报告,均讳言庆长琉球之役的日琉关系,等等。③杨仲揆:《琉球古今谈——兼论钓鱼台问题》,台北:台湾商务印书馆1990年版,第64~65页。3.琉球官方出版和汇编了《唐琉球问答属》、《旅行人心得》等文件。《唐琉球问答属》是由首里王府制作的,为避免“琉球漂流事件”④琉球漂流事件:明代中琉交往后,琉球船只或贡船失事飘到中国沿海的有12起。明清两朝对包括琉球漂民在内的漂风难民均有救助、安置和抚恤遣返的做法,形成以中国为中心,参与国包括朝贡国和非朝贡国(如日本)在内的海难救助机制。由于导致船舶漂流的主要原因是搞错了季风期,在“两属”时期,首里王府下达了严格遵守出港、归港期的命令,但即使这样,也不免有漂流事件的发生。参见赖正维:《清代中琉关系研究》,北京:海洋出版社2011年版,第56~60页;[日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第52页。透露出萨摩藩控制琉球的内幕、以应对中国官府的问答卷。其中第一条回答琉球王国统治疆域时,答案为“统治的疆域有中山府、南山府、北山府,南面的八重山、与那国岛,北面的大岛、喜界岛,西面的久米岛,东面的伊计岛、津坚岛等36岛”,而当时(奄美)大岛、喜界岛已经在萨摩藩的管辖范围内,这显然在向清朝刻意隐瞒。⑤[日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第52~53页。《旅行人心得》出版于乾隆二十四年(1759年),是印有中琉“标准答案”的小手册,为琉球华裔政治家蔡温所撰,目的是教育琉球入华的官员、官生和一般商人如何答复中国人可能提出的问题,最重要的是有关萨琉关系的问题。⑥杨仲揆:《琉球古今谈——兼论钓鱼台问题》,台北:台湾商务印书馆1990年版,第64~65页。

二、《万国公法》视野下藩属国的国际法地位

亚洲的“宗藩/朝贡体系”是以中国为中心、以中国之周边各邻国与中国形成的双边“封贡关系”为结构的国际体系。“万国公法体系”又称“条约体系”,则指伴随近代殖民扩张形成的,西方殖民列强主导的以“条约关系”为结构、以“万国公法”世界的国际秩序为基础的国际体系。⑦费正清提出了晚清时期与朝贡体制并存的“条约体系”一词。参见J. K. Fairbank, The Early Treaty System in the Chinese World Order, in J. K. Fairbank ed., The Chinese World Order: Traditional China’s Foreign Relations, Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press, 1969, pp. 257~275.近代西方国际法正式和有系统的传入中国是从19世纪开始的。然而,19世纪后期,清廷的藩属国如越南、缅甸、朝鲜等相继沦为欧美列强和日本的殖民地或保护国,宗藩/朝贡体制分崩离析。

(一)《万国公法》的传入及其对清政府外交的影响

如上所述,近代西方国际法正式和系统的传入中国是从19世纪开始的。美国传教士丁韪良(1827-1916)翻译的《万国公法》⑧《万国公法》一书,译自美国国际法学家亨利·惠顿(1785-1848)于1836年出版的《国际法原理》(Elements of International Law)一书,翻译者是美国传教士丁韪良(1827-1916),于1864年(同治三年)冬由北京崇实馆刊印发行。参见林学忠:《从万国公法到公法外交:晚清国际法的传入、诠释与应用》,上海:上海古籍出版社2009年版,第113页。是中国历史上第一本西方法学著作。《万国公法》在中国一经出版,在东亚世界引起很大震撼,翌年在日本便有翻刻本和训点本出版,在很短的时间内成为日本的畅销书,后陆续在朝鲜和越南相继翻刻刊行。⑨邹振环:《丁韪良译述〈万国公法〉在中日韩传播的比较研究》,载于复旦大学韩国研究中心编:《韩国学研究第七辑》,北京:中国社会科学出版社2000年版,第258~278页。19世纪初,中国逐渐成为西方列强在东亚的殖民目标,其间历经两次鸦片战争,到1901年《辛丑条约》的签订,中国彻底沦为半殖民地半封建社会。在这样的时代背景下,中国社会各阶层对西方国际法传入的态度是矛盾的。一方面,清政府的确有应用国际法与西方国家外交交涉成功的案例,例如1839年林则徐禁止销售鸦片⑩茅海建:《天朝的崩溃——鸦片战争再研究》,北京:三联书店1995年版,第104~112页。和办理“林维喜案”,①1839年7月,九龙尖沙嘴村发生中国村民林维喜被英国水手所杀的案件。对该案的研究,参见林启彦、林锦源:《论中英两国政府处理林维喜事件的手法和态度》,载于《历史研究》2000年第2期,第97~113页。又如普鲁士在中国领海拿捕丹麦船只事件②1864年4月,普鲁士公使李福斯乘坐“羚羊号”军舰来华,在天津大沽口海面上无端拿获了3艘丹麦商船。总理各国事务衙门当即提出抗议,指出公使拿获丹麦商船的水域是中国的“内洋”(领水),按照国际法的原则,应属中国政府管辖,并以如普鲁士公使不释放丹麦商船清廷将不予以接待相威胁。在这种情况下,普鲁士释放了2艘丹麦商船,并对第3艘商船赔偿1500元,事件最终和平解决。关于此案及清政府援引《万国公法》的经过,参见王维俭:《普丹大沽口船舶事件和西方国际法传入中国》,载于《学术研究》1985年第5期,第84~90页。等,这些外交纠纷的顺利解决促成清政府较快地批准《万国公法》的刊印;另一方面,清政府及其官员对国际法则倾向于从器用的层面做工具性的利用,追求对外交涉时可以援引相关规则以制夷。

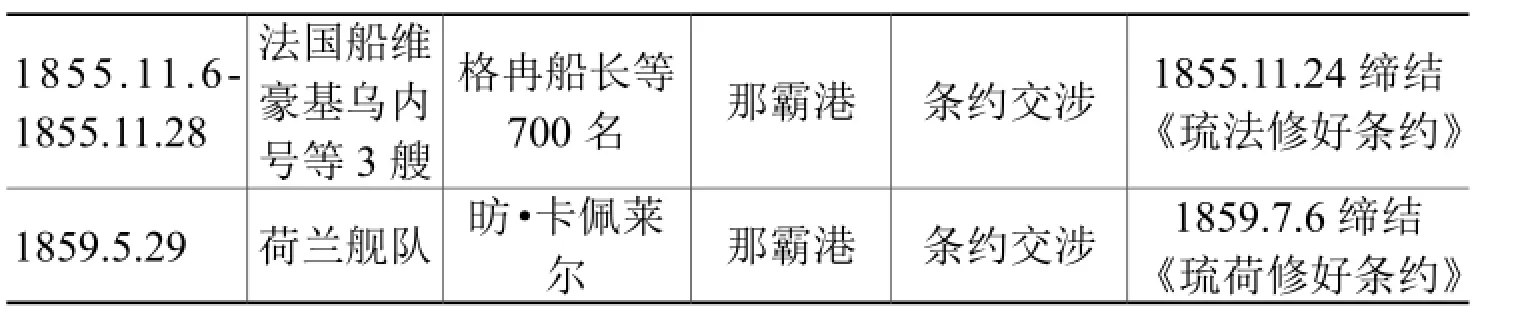

甲午战争爆发前后那段时期的“国际社会”是有特定涵义的,它是以欧洲为中心、由主权独立的欧洲国家组成,进而形成一套体现西方价值观、有约束力的近代国际法规则体系,又被称为“国际法共同体”或“文明共同体”。琉球大学历史学者西里喜行指出,东亚的近代是东亚各国、各民族与欧美列强间的相互关系的主客颠倒时代,也是东亚传统的国际制度即册封进贡体制,被欧美列强主导的近代国际秩序即万国公法所取代的时代。③[日]西里喜行著,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上)》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2010年版,第17页。我国汪晖教授也认为,清朝与欧洲列强之间的冲突不是一般的国与国之间的冲突,而是两种世界体系及其规范的冲突,即两种国际体系及其规范的冲突,④汪晖:《中国现代思想的兴起(上卷)》,北京:三联书店2004年版,第680页。这两种国际体系就是“朝贡体系”和近代“万国公法体系”。“万国公法体系”中,世界各国被分为“文明”、“不完全文明”、“野蛮”和“未开化”多个领域(见表1),中国等亚洲国家被视为“野蛮国”,只能适用国际法的部分原则,不能享有国家主体的完全人格。最能反映这种秩序架构上的国家权利的差异,莫过于以片面最惠国待遇、领事裁判权、协定关税为核心内容的诸多不平等条约。这种国际秩序是不折不扣的“西方中心主义”,而19世纪末20世纪初的政治现实却是在这种偏见下展开的。⑤林学忠:《从万国公法到公法外交:晚清国际法的传入、诠释与应用》,上海:上海古籍出版社2009年版,第243页。

(二)《万国公法》中的“藩属国”

比较19世纪《万国公法》和20世纪《奥本海国际法》⑦《奥本海国际法》可谓是在20世纪对《万国公法》起到承前启后作用的巨著。该书的雏形是国际法学者奥本海(1858-1919)在1905-1906年出版的《国际法》两卷集,奥本海因此当选剑桥大学惠威尔国际法讲座教授。之后第二版由奥本海本人修订。此后《奥本海国际法》经过罗纳德·罗克斯伯勒、阿诺德·麦克奈尔,以及赫希·劳特派特等多位国际法知名学者多次修订并出版,被称为“剑桥书”。参见[英]詹宁斯、瓦茨修订,王铁崖等译:《奥本海国际法(第一卷,第一分册)》,北京:中国大百科全书出版社1998年版,第III~V页。这两部国际法经典著作不难发现,“殖民地”其实是现代国际法所称“国际人格者”中的一种类型。而与“宗藩/朝贡体制”联系最密切的“被保护国”、“半主权国”、“藩属国”等国际法概念,在《万国公法》中被纳入“邦国自治、自主之权”专章论述。现代国际法意义上的“国际人格者”是指享有法律人格的国际法的主体,“国际人格者”享有国际法上所确定的权利、义务和权力。⑧[英]詹宁斯、瓦茨修订,王铁崖等译:《奥本海国际法(第一卷,第一分册)》,北京:中国大百科全书出版社1998年版,第90页。探讨近现代国际法“国际人格者”的内涵和法律概念的变化与演进,对于分析琉球近现代国际法地位具有重要启示。围绕着琉球地位问题,中日琉三方的外交交涉中,官方曾援引并运用《万国公法》的原则、规则和理论。

了解19世纪语境下“国际人格者”的类型和内涵,就要从《万国公法》中寻找初始的轨迹。参照丁韪良的中译本⑨应注意的是,《万国公法》(北京:中国政法大学出版社2003版)的点校人何勤华教授指出,丁韪良在翻译时,不仅对原书的结构、体系、章节有过调整,也对其中的内容作了大量删节。如第一卷第二章第二十三节“日耳曼系众邦会盟”,原文有近90%的内容被丁韪良所删,翻译出来的只是几点摘要。此外,由于受历史条件和译者中文水平的局限,还存在较多不成功的翻译之处(参见[美]惠顿著,[美]丁韪良译,何勤华点校:《万国公法》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2003年版,“点校者前言”第51页)。鉴于此,笔者在写作本文时,特别注意对比《万国公法》中英文版本的差异,尤其关注英文版本中有论述,而中文版本中存在删节或省略的部分。和1866年由波士顿的利特尔&布朗公司出版的英文第八版⑩中国国家图书馆外文馆藏有Elements of International Law的多个版本,该书自1836年第一版问世后就多次再版,主体内容并无大的改动,而是由不同的编辑者加以注释,或添加国际公约作为附录。笔者参阅的是1866年在波士顿出版的第八版,该版本由Richard Henry Dana编辑并注释。参见Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, p. viii.这2个版本可知,惠顿所著的《万国公法》①丁韪良翻译的《万国公法》由北京崇实馆1864年出版,该中文版译自Elements of International Law: With a Sketch of the History of the Science的第六版,即由William Beach Lawrence (1800-1881)编辑的注释版(Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1855)。参见林学忠:《从万国公法到公法外交:晚清国际法的传入、诠释与应用》,上海:上海古籍出版社2009年版,第113页。在第一卷第二章中提到了“国”、“半主之国”、“被保护国”、“藩属”等具有或部分具有“国际人格者”资格的类型,尤以对“藩属”主权问题的论述值得关注。

对于“国”的定义,《万国公法》中有一段文字:“所谓国者,惟人众相合,协力相助,以同立者也。”为说明“国家”的构成要件,惠顿特别提到,“盖为国之正义,无他,庶人行事,常服君上,居住必有定所,且有领土、疆界,归其自主。此三者缺一,即不为国矣。”②[美]惠顿著,[美]丁韪良译,何勤华点校:《万国公法》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2003年版,第25~26页。19世纪的国际法中,“国家”的要件主要是定居的居民、领土和疆界,③Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, p.22.这和现代国际法对国家的认定标准相比明显宽松不少。《万国公法》中,国又分为“自主之国”和“半主之国”。“自主之国”是“无论何等国法,若能自治其事,而不听命于它国,则可谓自主者矣”;④[美]惠顿著,[美]丁韪良译,何勤华点校:《万国公法》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2003年版,第37页。而“恃他国以行其权者……盖无此全权,即不能全然自主也”则被称为“半主之国”,除阿尼合邦、戈拉告依据条约属于“半主之国”外,保护国、附庸国也被归入“半主之国”之列。⑤Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, pp. 45~46.主权又分为对内主权和对外主权,“主权行于内,则依各国之法度,或寓于民,或归于君;主权行于外,即本国自主,而不听命于他国也。各国平战、交际,皆凭此权”。⑥[美]惠顿著,[美]丁韪良译,何勤华点校:《万国公法》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2003年版,第35~36页。

《万国公法》中单列一节论及藩属国(或藩邦)。⑦惠顿的《万国公法》第二章第37节题目就是“Tributary States”,参见Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, pp. 48~49.“进贡之国并藩邦,公法就其所存主权多寡而定其自主之分”。⑧[美]惠顿著,[美]丁韪良译,何勤华点校:《万国公法》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2003年版,第41页。即藩属国的主权,并不因为其进贡于宗主国的事实而必然受到减损,而是取决于其自主性。《万国公法》列举了几类“藩邦”:⑨[美]惠顿著,[美]丁韪良译,何勤华点校:《万国公法》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2003年版,第41~42页。第一,“欧罗巴滨海诸国,前进贡于巴巴里(埃及以西的北非伊斯兰教地区)时,于其自立、自主之权,并无所碍”,即欧洲主要海洋国家并不因向巴巴里的进贡行为而失去独立自主的主权国家地位;第二,“七百年来,那不勒斯王尚有屏藩罗马教皇之名,至四十年前始绝其进贡。然不因其屏藩罗马,遂谓非自立、自主之国也”。即那不勒斯自17世纪至1818年期间一直向罗马教皇进贡,但这并不意味着那不勒斯王国的主权有所减损。⑩Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, p. 49.

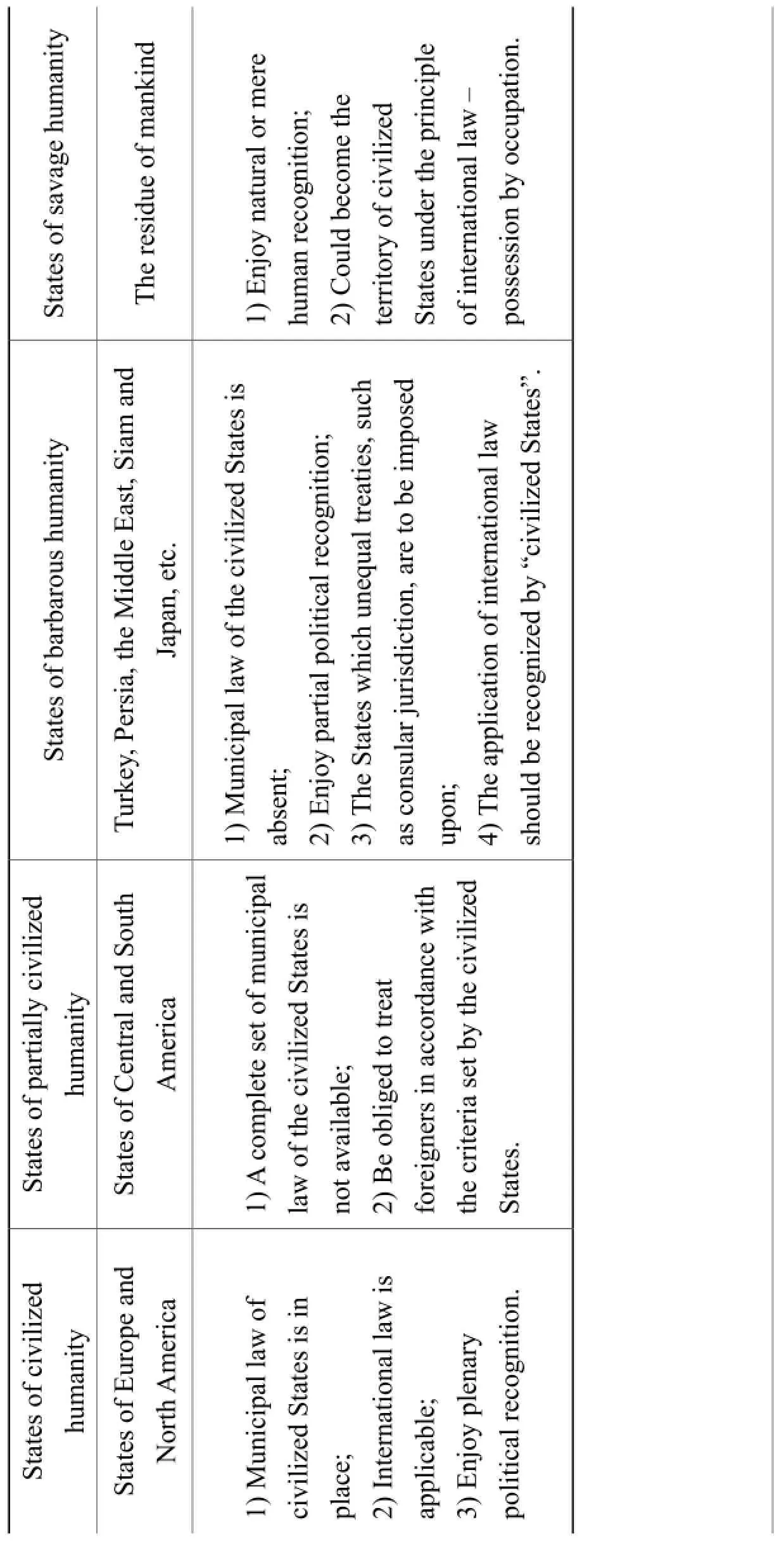

(三)清朝维护藩属国朝鲜、缅甸、越南的“公法外交”

宗藩(或藩属)制度作为中国古代国家政体的重要内容之一,早在汉朝时就已经产生。沿袭汉代,唐代的藩属制度又有所创新,是以在边疆少数民族聚居区广设羁縻府州为藩属主要实体的创新阶段。明沿袭唐代、元代的藩属制度亦有新的举措。清王朝集历代藩属制度之大成。①黄松筠:《中国藩属制度研究的理论问题》,载于《社会科学战线》2004年第6期,第121页。宗主国和藩邦之间的经济交流主要是通过“朝贡”、“赏赐”及朝贡附载贸易来实现的。费正清②费正清对朝贡体制的理论基础——华夏中心主义意识,以及朝贡关系融政治、贸易、外交于一体的特征,都有开创性研究。他还以“冲击—反应”模式为框架,来研究近代中国的走势。此后许多学者分别提出“华夷秩序”、“天朝礼治体系”、“中国的世界秩序”、“东亚的国际秩序”等,被视为古代中国的中外关系、外交制度、外交观念等,但都与朝贡体制有关。费正清的上述观点虽可概括朝贡体制的结构,但仍应注意,亚洲内陆游牧部落与华夏文化圈内的“朝贡国”虽然同处在“朝贡体系”之中,但仍存在很大的差异;暹罗、缅甸等“朝贡国”与欧洲国家也存在差异,因为这些“朝贡国”与中国保持着正式的“封贡关系”,所以不能和欧洲国家划归一类。参见王培培:《“朝贡体系”与“条约体系”》,载于《社科纵横》2011年第8期,第115~117页。认为,朝贡体制是以中国为中心形成的圈层结构:第一层是汉字圈,有几个最邻近且文化相同的“属国”构成,包括朝鲜、越南、琉球和一段时期的日本;第二层是亚洲内陆圈,由亚洲内陆游牧和半游牧的“属国”和从属部落构成;第三层是外圈,一般由关山阻隔、远隔重洋的“外夷”组成,包括日本、东南亚和南亚一些国家以及欧洲。③John King Fairbank ed., The Chinese World Order, Traditional China’s Foreign Relations, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968, p. 2.清王朝将海外各国大致分两类:一是“朝贡国”(见表2),即正式建立外交关系的国家。这7个藩属国包括朝鲜、琉球、安南(今越南)、暹罗(今泰国)、缅甸、南掌(今老挝)和苏禄(今菲律宾苏禄群岛);二是无正式外交关系,而有贸易往来的国家,包括葡萄牙、西班牙、荷兰、英国、法国等西方国家。④李云泉:《朝贡制度史论——中国古代对外关系体制研究》,北京:新华出版社2004年版,第134~148页。

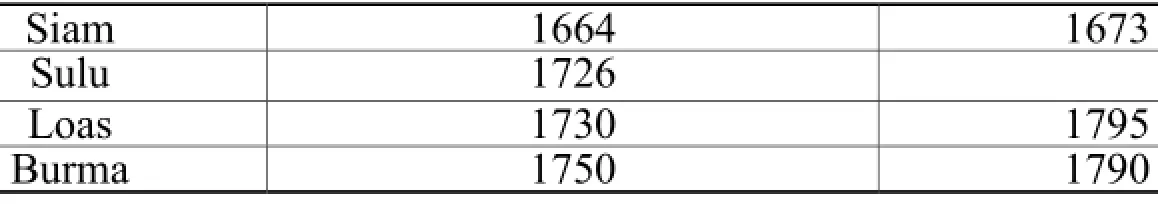

表2 清代主要朝贡国的贡封时间一览表45

清政府与藩属国之间的外交事务,并不仅限于藩属国地位问题,往往还关联到国际条约、交战规则和中立法、国际习惯法、国家领土边界等复杂问题,实非本文篇幅可以囊括,不过藩属国的地位仍是清政府外交交涉中绕不开的议题。在对待朝鲜、越南、缅甸这几个藩属国自身是否为“自立之国”,以及如何对藩属国的安全提供保护或支援的问题上,清政府的外交政策和处理方法有所不同。

朝鲜在中国众多藩属国有“小中华”之称。清政府维护中朝宗藩关系是全方位的,不仅派出军队,更不惜改变传统的方式直接介入朝鲜的内政与外交,并应用国际法和条约体制以巩固宗主国地位,即使1885年《天津会议专条》签订后也并不承认朝鲜具有“自主之国”的国际地位。1876年日本制造“江华岛事件”后,清政府采用了均势外交,鼓励朝鲜对欧美开战,以图用势力均衡的局面保住朝鲜。当中国明白传统中华世界秩序原理已无法维持中朝关系时,开始改变外交策略,甚至应用国际法的规则试图维持中朝藩属关系,除了1882年“壬午兵变”后在形式上保留朝鲜自主、实质开始介入朝鲜内政外交之外,1882年10月还和朝鲜缔结《中国朝鲜商民水陆贸易章程》,用条约体制将传统中朝宗藩关系明文化。⑥林学忠:《从万国公法到公法外交:晚清国际法的传入、诠释与应用》,上海:上海古籍出版社2009年版,第276~278页。

清政府出兵援越是基于“保藩固圉”⑦马大正主编:《中国边疆通史丛书·中国边疆经略史》,郑州:中州古籍出版社2000年版,第398页。的边防思路,意图御敌于国门之外,起初并不想和法国直接冲突。然而,法国在吞并越南的进程中,以外交交涉和缔结条约为主,以销毁中越宗藩关系证据为辅。首先,法国认为,按西方国际法的属国制度,“如作某国之主,则该国一切政事吏治皆为之作主,代其治理”,所以中国并没有真正管辖越南。⑧郭廷以等编:《中法越南交涉档(二)》,台北:“中央研究院”近代史研究所1962年版,第927页。随后法国要求中国在法越战争期间作为第三国,必须中立。⑨例如1883年6月,李鸿章收到法国来函称:“法越现已交兵,按照公法,局外之国不得从旁扰与,似须法越战事稍定乃可就议”。参见郭廷以等编:《中法越南交涉档(二)》,台北:“中央研究院”近代史研究所1962年版,第910页。其次,法国运用《中法简明条约》(1884.5.11)、法越《第二次顺化条约》(1884.6.6)等系列条约,逐步做实从越南为“自主之国”到越南为法国被保护国的国际地位。尤为甚者,在《第二次顺化条约》签约换文前,法国全权公使巴德诺逼迫阮朝交出清封敕的镀金驼钮印玺,熔铸为银块,⑩张登桂等编:《大南实录(正编第五纪,卷4)》,东京:庆应义塾大学1961-1981年版,第4页。转引自李云泉:《中法战争前的中法越南问题交涉与中越关系的变化》,载于《社会科学辑刊》2010年第5期,第155页。借以永久销毁中越宗藩关系的证据。对中法就越南藩属国地位展开的交涉,有评价称,“从一开始就像中日在朝鲜属国地位问题上的交涉一样,注定是一场无果而终的拉锯战”。①李云泉:《中法战争前的中法越南问题交涉与中越关系的变化》,载于《社会科学辑刊》2010年第5期,第151页。

中缅官方关系直至18世纪中期才建立。面对英国就缅甸藩属地位的质疑,驻英公使曾纪泽断然否认并寻找缅甸为中国属国的论据和实物证据。曾纪泽反驳英国提出的乾隆35年(1770年)中缅条款为两国平等条约的说法,指出它只是缅甸对华的“降表”而已。②电文内容为:“缅王印,乾隆五十五年颁给,系清汉文尚方大篆,银质饰金驼纽,平台方三寸五分,厚一寸,其文曰‘阿瓦缅甸国王之印’。特电。”参见何新华:《试析清代缅甸的藩属国地位问题》,载于《历史档案》2006年第1期,第75页。总理衙门把清政府颁给缅甸国王封印的尺寸、封印上的字体及内容都曾给曾纪泽以电文说明。③王彦威:《清季外交史料(卷61)》,北京:故宫博物院1932年刊本,第29页。至于英方所提缅甸在英缅冲突中没有向中国提出保护请求这一说法,清政府虽从缅甸违反属国义务这一角度作了解释,④何新华:《试析清代缅甸的藩属国地位问题》,《历史档案》2006年第1期,第75页。但对英国侵占缅甸并没有采取实质性的干预,对缅外交多体现实用主义色彩。18世纪末至19世纪初,缅甸的南方邻国暹罗开始强大并对缅甸造成巨大威胁,其后英国进入缅甸南部和西部,缅甸正是在这一时期频繁进贡中国。缅甸对其藩属国的身份实际上采取了“暧昧态度”,⑤缅甸的暧昧态度表现在缅甸国王对待1790年乾隆赐给的封印态度上。当“使臣携归华文大印,其状如驼,缅王恐受制于清,初不愿接受,顾又不愿舍此重达三缅斤(十磅)之真金,乃决意接受而使史官免志其事。”参见[英]哈维著,姚梓良译:《缅甸史(下册)》,北京:商务印书馆1973年版,第453页。它既不把中国作为天朝上国,也从未主动承认是中国的藩属国。⑥何新华:《试析清代缅甸的藩属国地位问题》,载于《历史档案》2006年第1期,第72页。

纵观19世纪中后期,“英之于缅,法之于越,倭之于球,皆自彼发难。中国多事之秋,兴灭继绝,力有未逮”。⑦路凤石:《德宗实录》(卷232,光绪十二年九月),北京:中华书局1987年版。19世纪末,甲午一战、清国败北。当“宗藩/朝贡体制”崩溃后,中国不得不彻底地放弃天朝观念,接受了以“万国公法体制”为基础的西方世界观。

三、从中日“琉球交涉”看近世琉球的历史和国际法地位

19世纪,日本明治政府用近10年的时间,以武力强行将琉球王国划入日本的版图,这在历史上称为“琉球处分”。围绕着“琉球处分”,伴随着同时期欧美列强在亚洲推行的殖民主义,中日两国展开了漫长的磋商谈判,直到1880年“分岛改约案”琉球问题搁置,以致成为中日之间的“悬案”。

(一)1871-1880年中日之间的“琉球交涉”

中日之间的“琉球交涉”早期可溯源到1871年的“生番事件”(又称“牡丹社事件”),⑧生番事件:同治10年(1871年)11月,琉球国太平山岛一艘海船69人遇到飓风,船只倾覆。幸存的66人凫水登山,11月7日,误入台湾高山族牡丹社生番乡内,和当地居民发生武装冲突,54人被杀死,幸存的12人在当地汉人杨友旺等帮助下,从台湾护送到福建。同治11年(1872年)2月25日,福州将军兼署闽浙总督文煜等人将此事向北京奏报,京城邸报对此作了转载。参见米庆余:《琉球漂民事件与日军入侵台湾(1871-1874)》,载于《历史研究》1999年第1期,第21~36页。最后以1874年签订《北京专条》得以解决。然而该事件不仅由清廷赔款,⑨米庆余:《琉球漂民事件与日军入侵台湾(1871-1874)》,载于《历史研究》1999年第1期,第21~36页。而且日本在攫取“保民义举”名义后也仍在加紧对琉球的吞并,1879年日本废掉琉球藩改名冲绳县,县官改由日本委派。⑩鞠德源:《评析30年前日本政府〈关于尖阁诸岛所有权问题的基本见解〉》,载于《抗日战争研究》2002年第4期,第147~166页。清政府于当年即对日本单方面处分琉球提出外交照会,表示强烈抗议。

经美国卸任总统格兰特的调停,中日展开了对琉球“分岛加约案”的谈判,琉球“二分方案”和“三分方案”是当时都曾讨论过的方案。①[日]西里喜行著,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上)》,北京:社会科学文化出版社2010年版,第312页。1880年10月21日,依据日方所倾向的“二分方案”,中日达成协议并草签了《琉球条约拟稿》和《酌加条款》。《琉球条约拟稿》(原文为中文)规定,“大清国大日本国公同商议,除冲绳岛以北,属大日本国管理外,其宫古八重山二岛,属大清国管辖,以清两国疆界,各听自治,彼此永远不相干预”。②《琉球處分條約案に關する件(琉球処分条約案に関する件)》,载于日本外务省编:《日本外交年表并主要文书1840-1945(上巻)》,东京:原书房1965年版,第81~85页;鞠德源:《评析30年前日本政府〈关于尖阁诸岛所有权问题的基本见解〉》,载于《抗日战争研究》2002年第4期,第147~166页。不过最终正式签约时,清政府拒绝签署双方约定的琉球分割方案,《琉球条约拟稿》成为废约。至于清政府最终拒绝在“分岛改约”方案上签约的原因,史学界有几种解释:一是“清俄关系缓和主因说”。该说法主张,围绕着伊犁问题的俄清谈判进展顺利,清政府对“分岛改约”态度中途发生变化也是受其左右;③[日]植田捷雄:《琉球の归属を绕る日清交涉》,载于东京大学东洋文化研究所编:《东洋文化研究所纪要(二)》,1951年。二为“清廷内部矛盾说”。由于清廷官员内部严重分歧,清政府采纳李鸿章“支展延宕”之拖延政策,决定不批准协议草案,初衷是保存琉球社稷和避免“失我内地之利”。④米庆余:《琉球历史研究》,天津:天津人民出版社1998年版,第226页。三是“琉球人林世功自杀影响说”。⑤[日]西里喜行著,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上册)》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2010年版,第35页。在清政府内部展开是否应该签署琉球分割条约的争论期间,为了阻止该条约签署,流亡清国的琉球人林世功写了一份决死的请愿书后自杀身亡。林世功自杀事件也给清廷内部关于是否应当签署条约争论的结局以一定的影响。

最终清政府在中日甲午战争中战败,被迫于1895年签署《马关条约》,⑥《马关条约》又称《下关条约》,甲午战争清朝战败后,清政府和日本政府于1895年4月17日(光绪二十一年三月二十三日)在日本马关(今下关市)签署的条约,原名《马关新约》,日本称为《下关条约》或《日清讲和条约》。清朝代表为李鸿章和李经芳,日方代表为伊藤博文和陆奥宗光。割让台湾、澎湖、辽东半岛给日本,对琉球问题更是“无力回天”。不过,直至甲午战争爆发前,中日双方仍认知琉球的地位悬而未决。日本吞并琉球后,不满日本统治的琉球人流亡清朝以求复国,被称为“脱清人”。

(二)近世琉球地位的国际法分析

历史学者西里喜行观察到,围绕着琉球的归属即主权问题,不仅中日在不同阶段的外交谈判中大量运用《万国公法》,而且1875-1879年琉球王国陈情特使在东京的请愿活动也曾引用《万国公法》来对抗琉球乃日本专属的主张。⑦东京的琉球陈情使以波兰曾经附属于普鲁士、奥地利和俄罗斯三国为例,指出《万国公法》也同样允许两属国家的存在。参见[日]西里喜行,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上)》,北京:社会科学文化出版社2010年版,第29~32页。从时际法⑧时际法,或称过渡法,是指解决法律时间抵触的法律,也就是决定法律时间适用范围的法律。领土争端中,时际法是需要考虑的重要法律因素。国际法上的“时际法”是在国际常设仲裁法院“帕尔马斯岛案”中,由仲裁员胡伯首先提出,并逐步在领土争端解决实践和条约法中得到发展。他所表述的时际国际法是:“一个法律事实应当按照与之同时的法律,而不是按照因该事实发生争端时所实行的法律或解决这个争端时所实行的法律予以判断”。参见The Island of Palmas Case (or Miangas), United States of America v. The Netherlands (1928), Permanent Court of Arbitration, pp. 4~6, p. 37.视角看,对待19世纪后半叶琉球国际法地位这样的议题,运用当时的国际法即《万国公法》并结合殖民入侵背景下亚洲的政治格局,才能得出相对客观的结论。当然,现代国际法理论尤其是有关国家和主权以及领土争端理论和实践,对于现代人更好地理解琉球的国际法地位是有辅助作用的。近世琉球的历史和法律地位应从以下几个方面予以论证。

第一,历史上近世琉球“暗属日本”的状态,并不意味着该时期萨摩藩对琉球的征服行为符合领土取得的国际法;而中日琉球交涉时日方代表的“琉球专属日本论”既不符合历史,从当时的国际法看也站不住脚。如上文所述,自1609年萨摩藩入侵后,琉球与中日维持着“明属中国、暗属日本”的两属模糊状态。然而,以武力征服琉球王国的不是代表中央政权的江户幕府,而是地方政权——萨摩藩。从1609年到江户末期,即使是当时的江户幕府也没有将琉球并入领土的意图,而是将琉球视为日本六十余州之外的独立王国:例证一,1610年5月江户幕府的大老(幕府最高执政官)本多正纯写信给萨摩藩主岛津家久,要求按照接待朝鲜国使节的待遇把被俘的琉球国王带到江户;⑨何慈毅:《明清时期琉球日本关系史》,南京:江苏古籍出版社2002年版,第55页。例证二,同年9月,幕府秀忠将军公开向琉球国王承诺,“尚氏世代为琉球国王,现在应速速回国,祀奉祖先,仰本朝之威德,将其国永传子孙。”⑩[日]黑板胜美:《德川实纪(第1编)》,载于国史大系编修会编:《新订增补国史大系(第38卷)》,东京:吉川弘文馆1929年版。因此,笔者认为,1609年萨摩藩作为地方政府入侵琉球的行为并未经过中央政府的授权或追认,并不符合领土取得的形式要件。那么结合历史,萨摩藩武力征服琉球之后是否又产生取得琉球领土主权的效果?征服是一国不经过他国同意,以武力将其领土置于统治之下,为古代国际法承认的领土转移方式,但晚近国际法已经不再承认这是取得领土主权的合法方式。①苏义雄:《平时国际法》,台北:三民书局1993年版,第178页。而根据一般国际法,以征服取得领土往往需要完成2个步骤:其一是击溃并灭亡一国;其二是灭亡一国后吞并该国。②Suya P. Sharma, Territorial Acquisition, Dispute and International Law, The Hague/Boston/ London: Martinus Nijhof f Publishers, 1997, p. 143.与1879年日本中央政府出兵琉球并改其为冲绳县的做法不同,萨摩藩入侵琉球后,不仅奉中央命令放回琉球国王,琉球还长期维持自己的政体和对琉球的统治。此后为了从中琉贸易中获利,萨摩藩不但没有斩断中琉之间的宗藩/朝贡关系,相反,萨摩藩和琉球都选择向包括中国在内的国际社会刻意隐瞒琉萨之间的关系。即使从现代国际法看,琉球对内主权和对外主权都得以维系。因此,琉球迫于萨摩藩的威慑维持“暗属”日本的状态并不意味着日本取得近世时期琉球的主权。再后来,中日琉球交涉过程中,清政府认为琉球自成一国,世代受中国册封,奉中国为正朔,“琉球既服中国,而又服于贵国”;③米庆余:《琉球历史研究》,天津:天津人民出版社1998年版,第199页。日本以寺岛外务卿《说略》为代表的“琉球专属日本论”则坚持认为,琉球系日本“内政”,既非“自为一国”,也非“服属两国”,④以寺岛外务卿《说略》为代表的“琉球专属日本”论中,明治政府除了强调1609年萨摩藩入侵琉球王国前日本和琉球在地缘、地理、文化、种族等的相通性外,还提到琉球对日本的进贡早于中国,日本特设太宰府对琉球进行管理。日本还强调1609年后日本幕府已把琉球赐给萨摩藩,萨摩藩对琉球实施了包括军事、税收、法律制定等多方面的政治统治。米庆余:《琉球历史研究》,天津:天津人民出版社1998年版,第199页。双方交涉的核心是琉球的国际地位问题。日本的说辞无论从历史还是国际法来看都有很大的漏洞。1609年萨摩藩入侵琉球后,琉球不仅保有自己的政权和年号,还与包括日本幕府在内的亚洲周边国家展开外交和贸易交往。19世纪中期琉球以现代国际法意义上国家的名义,与美国、法国、荷兰三国签订通商条约。总之,从史实和中日琉外交关系史看,1609至1879年间近世琉球为中日“两属”符合历史,但近世琉球为独立王国也是事实,该时期琉球地位绝不是明治政府所称的“内政”问题,日本在此时期对琉球的“主权”更是无从谈起。

第二,历史上琉球既“中日两属”又为“独立之国”符合国际法。中日就琉球问题进行外交交涉期间,清政府主张琉球“既服中国,又服贵国”,同时又是自主之国。日本对此反驳,“既是一国,则非所属之邦土;既是所属之邦土,则非自成一国,”并用万国公法指出清国的“逻辑矛盾”,因此坚持琉球乃日本属邦之主张。⑤日本外务省编:《日本外交文书(第12卷)》,东京:日本国际联合协会1973年版。转引自[日]西里喜行著,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上)》,北京:社会科学文化出版社2010年版,第30页。西里喜行认为,“从传统的册封进贡体制的逻辑来说,内政上的自主国与对外关系上的属国这二者之间并无矛盾,但对于不承认册封进贡体制的日本来说,并没有什么说服力,因此中日两国的争论陷入胶着状态”。⑥[日]西里喜行著,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上)》,北京:社会科学文化出版社2010年版,第30页。清政府主张琉球既“中日两属”又“自成一国”是否有国际法依据?这就涉及《万国公法》有关国家构成的相关理论。⑦现有文献中已有用《万国公法》提到的欧罗巴滨海诸国和巴巴里之间关系与琉球的地位进行类比的初步尝试,参见王鑫:《从国际法的角度分析琉球法律地位的历史变迁》,载于《研究生法学》2009年第2期,第112~120页;王鑫:《从琉球法律地位历史变迁的角度透析钓鱼岛争端》(硕士论文),北京:中国政法大学2010年版,第8页;张毅:《琉球法律地位之国际法分析》(博士论文),北京:中国政法大学2013年版,第63~64页。历史上也曾有类似解读,例如,为对抗明治政府提出的琉球“专属日本”主张,东京的琉球陈情使以波兰曾经附属于普鲁士、奥地利和俄罗斯三国为例,指出《万国公法》也同样允许两属国家的存在。参见[日]西里喜行编:《琉球救国请愿书集成》,东京:法政大学冲绳文化研究所1992年版。《万国公法》把现代国际法意义上的“国际人格者”分为“主权之国”、“半主之国”、“被保护国”、“藩属”等类型。作为区别于“主权之国”或“半主之国”的藩属国,“进贡之国并藩邦,公法就其所存主权多寡而定其自主之分”,⑧[美]惠顿著,[美]丁韪良译,何勤华点校:《万国公法》,北京:中国政法大学出版社2003年版,第41页。也就是说,藩属国的主权,并不因为其进贡于宗主国的事实而必然受到减损,而是取决于其自主性而定。1609年萨摩藩入侵,琉球从此成为明属中国、暗属日本的事实上的“两属”状态,一直持续到日本明治维新初年。作为藩属国,琉球有国内事务自主权,宗主国中国不干涉琉球内政,只是琉球国王即位的时候派出使者进行象征性的册封。⑨修斌、姜秉国:《琉球亡国与东亚封贡体制功能的丧失》,载于《日本学刊》2007年第6期。宗主国中国并不企图通过朝贡贸易获取利益,更多的是以赏赐的形式对藩属国进行经济资助,主要通过强大的政治、经济、文化号召力,保持对藩属国的影响,绝非靠武力征讨和吞并。期间,琉球对内仍维持其政治统治架构、对外则以国家的身份和法国、美国、荷兰缔结双边条约;琉球的内政虽受制于萨摩藩,民间风俗也逐渐日化,但只要当清使将到达琉球时,在琉球的日本人就会事先走避。本文认为,结合历史和当时的国际法,1609-1879年琉球既是中日“两属”又是独立自主的国家,二者并不矛盾。当然,自1879年被日本吞并、列入版图后,琉球则沦为日本的殖民地,主权也遭到减损,这是不争的事实。

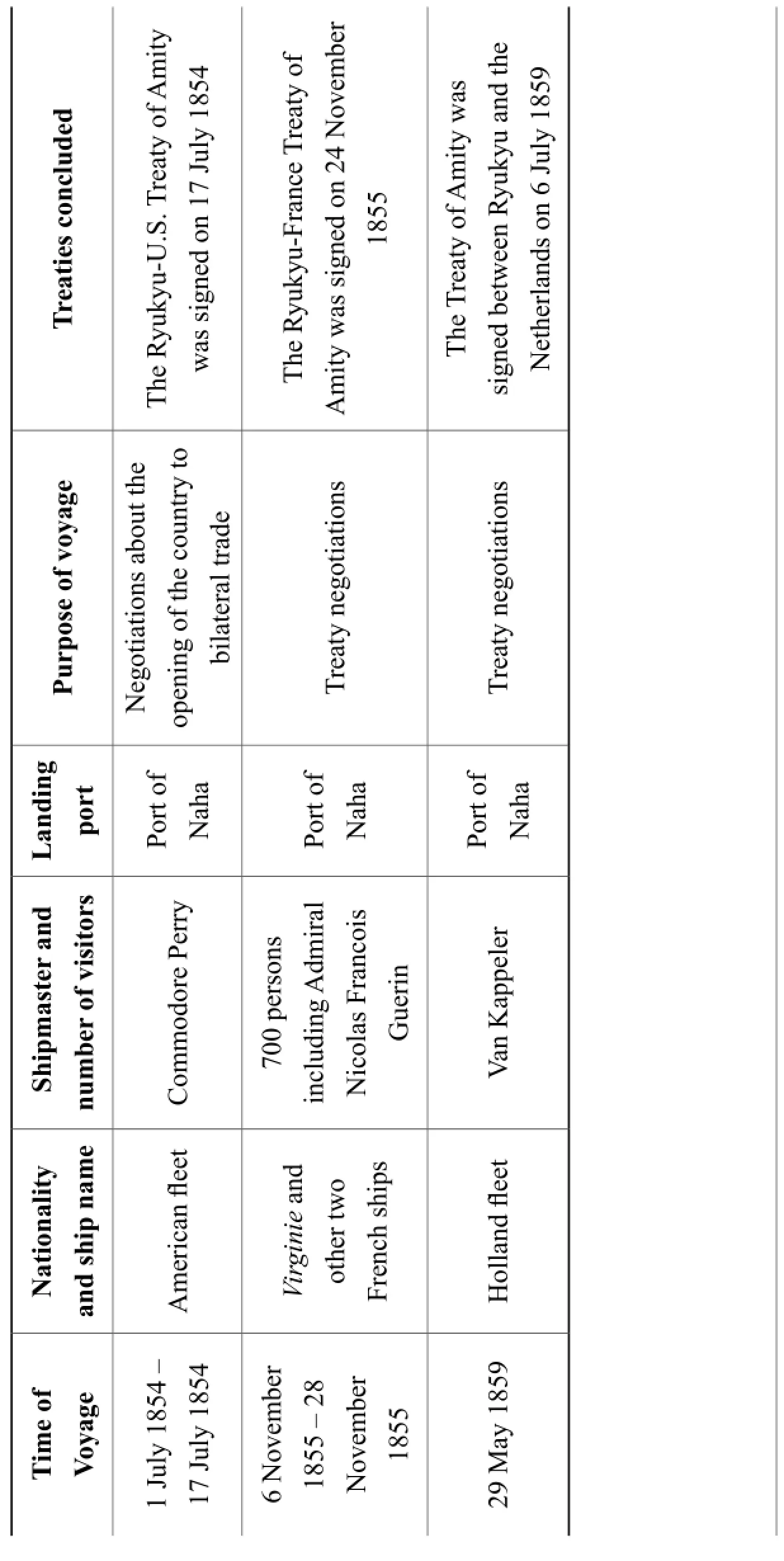

第三,琉球的自我认知及欧美列强态度均视琉球王国为“自成一国”。琉球末代国王尚泰将琉球定位为“属于皇国、支那……两国乃父母之国。”⑩[日]喜舍场朝贤:《琉球见闻录(卷之一二)》,东京:至言社1977年版。转引自[日]西里喜行著,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上)》,北京:社会科学文化出版社2010年版,第31页。1867年巴黎万国博览会时,琉球岩下佐次右卫门出席开幕式,自称是代表琉球王的使节。日本江户幕府虽向大会抗议称“琉球系江户幕府命令萨摩籓加以征服,因而成为萨摩籓的属国,不是独立于日本之外的国家”,但大会并未接受日本的抗议。①李明峻:《从国际法角度看琉球群岛主权归属》,载于《台湾国际研究季刊》2005年第2期,第56页。1875年到1879年,琉球陈情使以东京为中心进行请愿活动,反复强调要遵守“以信义行事”,表明了不愿放弃本国的政治独立,也不愿断绝中琉关系的意愿。②[日]西里喜行:《琉球救国请愿书集成》,东京:法政大学冲绳文化研究所1992年版。1879年,向清政府求救的琉球紫巾官向德宏撰文对寺岛外务卿的《说略》逐条进行反驳。③向德宏称,“日本谓敝国国体、国政,皆伊所立,敝国无自主之权。夫国体、国政之大者,莫如膺封爵、赐国号、受姓、奉朔、律令、礼制诸巨典。敝国自洪武五年入贡,册封中山王,改琉求国号曰琉球。永乐年间赐国主尚姓,历奉中朝正朔,遵中朝礼典,用中朝律例,至今无异。至于国中官守之职名,人员之进退,号令之出入,服制之法度,无非敝国主及大臣主之,从无日本干预其间者。且前经与法、美、荷三国互立约言,敝国书中皆用天朝年月,并写敝国官员名。事属自主,各国所深知。敝国非日本附属,岂待辩论而明哉?”参见王芸生:《六十年来中国与日本(第一卷)》,天津:大公报社1932年版,第127~129页。从当时国际社会的态度看,1840至1879年间欧美列强不仅知道琉球“两属”的状况,还怀着要求琉球开国的目的,秉持实用主义的外交政策在中日间周旋。比如,美国卸任总统格兰特就曾调停过中日间琉球问题。1879年在与李鸿章商讨调解琉球问题时,格兰特曾表示,“琉球原来为一国,而日欲将其并合而得以自扩。清国所力争之处,乃土地而非朝贡,甚具道理,将来需另设特别条款”,④[日]西里喜行著,胡连成等译:《清末中琉日关系史研究(上)》,北京:社会科学文化出版社2010年版,第307页。此后积极协调中日“分岛改约”的外交谈判。琉球以国家的身份和法国、美国、荷兰缔结了双边条约(参见表3),对外交往和对外缔约能力是当时的国际法对国家身份认定的重要指标,琉球“自成一国”因而也是当时国际社会所公认的。

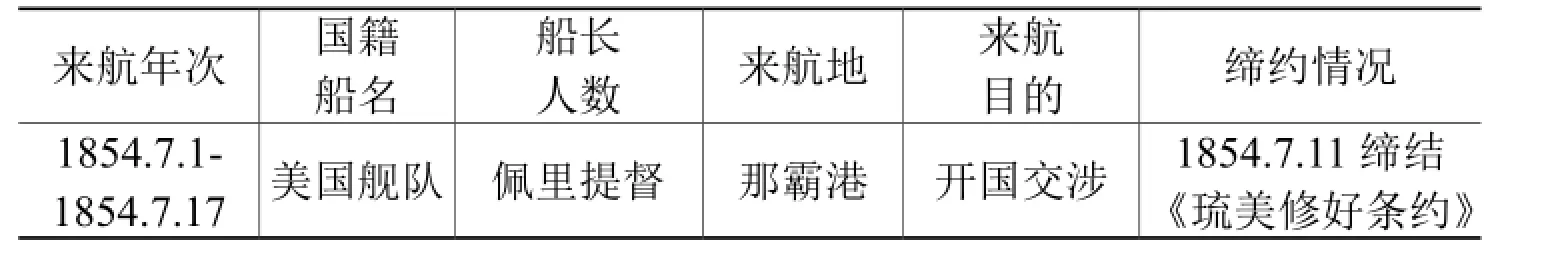

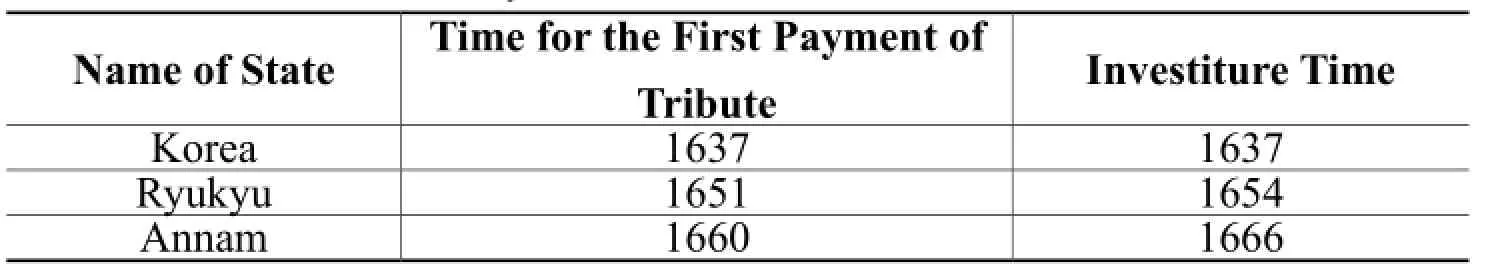

表3 鸦片战争后欧美舰船来琉以及缔结条约一览85

1855.11.6-1855.11.28700名那霸港条约交涉1855.11.24缔结《琉法修好条约》1859.5.29 荷兰舰队昉·卡佩莱法国船维豪基乌内号等3艘格冉船长等尔那霸港条约交涉1859.7.6缔结《琉荷修好条约》

第四,在面临外来侵略或殖民统治时,与琉球同属中华“宗藩/朝贡体制”的的外藩藩属国如越南、朝鲜和缅甸等,均以条约的形式解决其地位问题,随着时间的推移还最终取得独立。在中国的朝贡体系中,琉球和朝鲜、越南、缅甸等是同一类型的“外藩”,其中以琉球最为恭顺。然而,自从1879年日本在琉球“废藩置县”后,琉球就沦为日本的殖民地。与琉球情况不同的是,越南、朝鲜和缅甸脱离中国都有条约可循:1885年中法战争后,法国迫使中国签署《中法新约》,取代中国的宗主国地位,成为越南的保护国;1886年中英签订《中英缅甸条约》,英国以缅甸维持“十年一贡”换取中国对英国在缅权利的承认,逐步把缅甸变为自己的殖民地;1894年甲午战争后通过中日《马关条约》,中国放弃对朝鲜的宗主国地位。可见,清末中国周边藩属国法律地位变更的“国家实践”为,不仅用条约予以确认,还经过宗主国中国的确认。但是,从1879年日本吞并琉球至二战结束,中日间除了协商过1880年“分割琉球条约稿”之外,既没有就琉球主权之变更,也没有对琉球疆域的安排达成正式协议。时过境迁,20世纪,上述原属中华朝贡体系的藩属国命运多舛,但都摆脱了殖民统治,如今在联合国框架下都是独立的国家。

19世纪中后期,中日之间的“琉球交涉”是在“宗藩/朝贡体制”和“万国公法体制”之间“文明的冲突”背景下展开的。事实证明,面对列强的入侵和国际格局的巨大冲击,国力、军力衰落的清政府完全寄希望于国际公法并以“据理诘问为正办”,⑥1877年4月12日,琉球紫巾官向德宏乘船到闽向清朝求助,面见闽浙总督何璟和福建巡抚丁日昌,呈递琉王陈情书,乞求代纾其国之难。面对驻日公使何如璋对日“阻贡不已,必灭琉球,琉球既灭,行及朝鲜”的警告和应对建议,李鸿章却主张:“(何如璋)所陈上、中、下三策,遣兵舶责问及约琉人以必救,似皆小题大作,转涉张皇。惟言之不听时复言之,日人自知理绌,或不敢遽废藩制改郡县,俾球人得保其土,亦不藉寇以兵。此虽似下策,实为今日一定办法。”参见《李鸿章全集·译署函稿》,卷八,第1页。却对西方国际法只知其“器用”不知其“巧用”,教训惨重。晚清维新运动著名活动家唐才常指出,对外交涉挫败“虽由中国积弱使然,亦以未列公法之故,又无深谙公法之人据理力争。”⑦唐才常:《拟开中西条例馆条例》,载于湖南省哲学社会科学研究所编:《唐才常集》,北京:中华书局1980年版,第27页。中日关于琉案交涉的结局,正好证明了这个道理。

四、琉球法律地位与钓鱼岛主权争端

日本外务省对钓鱼岛的“主权主张”与琉球因素密不可分。为了证明将钓鱼岛并入版图的行为符合国际法上的“先占”,日本不仅称“‘尖阁诸岛’在历史上始终都是日本领土的‘南西诸岛’的一部分”,还用冲绳县在19世纪末对钓鱼岛所谓的“实地调查”作为“历史证据”。⑧日本外务省:《“尖阁诸岛”问答》,下载于http://www.cn.emb-japan.go.jp/territory/ senkaku/question-and-answer.html,2016年10月12日;日本外务省:《关于尖阁诸岛的基本见解》,下载于http://www.cn.emb-japan.go.jp/territory/senkaku/basic_view.html,2016年10月12日。日本官方主张中,历史与国际法的领土争端理论和条约法结合十分明显。此外日本学者不仅否认中国对钓鱼岛的“原始发现”和“最先主权持有人的地位”,还提出对日本有利的钓鱼岛“主权主张”。⑨在有关钓鱼岛的国际法研究中,具有代表性的日本学者论著包括:[日]入江启四郎:《尖阁列岛海洋开发の基盘》,载于《季刊·冲绳》1971年3月,第56页;[日]入江启四郎:《日清讲和と尖阁列岛の地位》,载于《季刊·冲绳》1972年12月,第63页;[日]奥原敏雄:《尖阁列岛の领有权问题》,载于《季刊·冲绳》1971年3月,第56页;[日]尾崎重义:《关于尖阁列岛的归属》,载于《参考》1972年总第263号;[日]绿间荣:《尖阁列岛》,那霸:ひるぎ社1984年版;Unryu Suganuma, Sovereign Rights and Territorial Space in Sino-Japanese Relations-Irredentism and the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000;Shigeyoshi Ozaki, Territorial Issues on the East China Sea: A Japanese Position, Journal of East Asia and International Law, No. 3, 2010;[日]尾崎重义:《尖阁诸岛与日本的领有权》,载于《外交》2012年第12期;[日]石井望:《尖阁前史(ぜんし)、无主地(むしゅち)の一角に领有史料有り》,载于《八重山日报》2013年8月3日(平成二十五年八月三日)。本文认为,考察琉球王国的地理范围以及中琉疆界分界,对于进一步从历史和地理角度论证钓鱼岛主权归属具有重要的意义;而1429年至1879年间的中日琉史料更是佐证我国钓鱼岛主权主张的重要历史证据。总的来看,钓鱼岛自古属于中国而不属于琉球,这不仅有来自中日琉三方的史料佐证,还有社会文化和地理水文等方面的依据。

(一)钓鱼岛由中国人而非琉球人先发现具有社会文化和地理水文等原因

钓鱼岛自明朝初年以来一直是中国的领土,并被用作航海的航标,从未成为琉球的领土,根本原因是琉球人未能在中国人之前发现钓鱼岛。⑩沙学骏:《钓鱼台属中国不属琉球之史地根据》,载于《学粹杂志》1972年第2期,第16页。而中国人能先发现钓鱼岛,除了社会文化因素外,还有地理地质水文等多重因素,具体如下:

1.琉球人的造铁、造船以及航船技术均较中国落后。琉球自古缺乏铁砂以供炼制熟铁,市面上甚至缺乏作为日用品的铁器,①沙学骏:《钓鱼台属中国不属琉球之史地根据》,载于《学粹杂志》1972年第2期,第16页。历史上琉球“地无货殖”“商贾不通”,琉球人“缚竹为筏,不驾舟楫”,②李廷机著:《李文节公文集》,载于陈子龙等编:《明经世文编(卷460)》,北京:中华书局1962年版。14-15世纪琉球的航海事业还处于低级阶段。由于琉球造船和航海技术落后,1392年朱元璋除了赐海舟给琉球外,还赐“闵人三十六姓善操舟者,令往来朝贡。”③龙文彬著:《明会要(卷77,外藩1,琉球)》,北京:中华书局1956年版。这些因素决定了琉球人不可能先发现钓鱼岛,而同时期的中国人具备造船、航海技术等条件,还发明了航海必需的指南针,中国先发现钓鱼岛则在情理之中。

2.从针路距离远近与指标岛屿多少而言,古代中国人发现钓鱼岛更具优势。据中国史料的针路和距离记载,从闽江口到钓鱼岛共约330公里,在基隆以西,有白犬屿、东沙山(岛)等小岛为(针路的)指标岛,十分便利。而基隆到钓鱼岛只有200公里,又有花瓶屿和彭佳屿为指标岛屿。反之从琉球的那霸到钓鱼岛则有460公里,由古米山到钓鱼岛也有410公里,比基隆到钓鱼岛的距离长了一倍有余。尤其重要的是,古米山和钓鱼岛之间,只有一个面积很小的赤尾屿作为指标岛。仅考虑到赤尾屿到古米山之间需要“过海”280公里之远,对于航海技术和造船工程很落后的琉球人,已经是不容易克服的困难;即使此后赤尾屿到钓鱼岛的距离仅130公里,但因远离那霸和古米山,联络十分不便,“过海”更加不容易克服。④沙学骏:《钓鱼岛属中国不属琉球之史地根据》,载于《学粹杂志》1972年第2期,第17页。

3.从黑潮流向、钓鱼岛海域的水文状况和册封使路线看,中国人较琉球人更容易“发现”钓鱼岛,日本的“无主地论”缺乏依据。自古以来,中国人航行琉球与日本,均靠信风及洋流,洋流即为黑潮⑤黑潮是太平洋北赤道洋流遇大陆后的向北分支,自菲律宾经台湾海峡及台湾东部,过八重山、宫古岛、钓鱼岛列屿,再往日本、韩国。黑潮时速平均为四、五海里,经过八重山、宫古岛、琉球诸岛和钓鱼岛列屿时,因风向和海岸冲击,又形成西侧向南洄流现象。参见杨仲揆:《中国·琉球·钓鱼岛》,香港:友联研究所1972年版,第135页。(也称为“日本洋流”)。我国古代海船,由闽江经台湾北部前往琉球,正是顺着黑潮支流、乘东南季风前进。中国海船由闽江口经台湾北方前往钓鱼岛,因为是顺着黑潮支流前进、速度加快,容易到达钓鱼岛,故容易发现钓鱼岛。而琉球海船欲过琉球海沟前往钓鱼岛,须逆黑潮前进,因受到阻力而速度减少,航行困难,使琉球“先发现”钓鱼岛更为不可能。⑥沙学骏:《钓鱼台属中国不属琉球之史地根据》,载于《学粹杂志》1972年第2期,第17页。

4.从海底地形看,中琉存在自然疆界。从对马海峡到钓鱼岛及赤尾屿南侧,经台湾北部沿海及全部台湾海峡,以及广东沿海,都是200米以内的大陆架,这是中国领土的自然延伸。另一方面,琉球群岛东南方的短距离以内,海深达到3000米以上,最深处深达7000多米。在琉球群岛与钓鱼岛之间存在的海沟叫“琉球海沟”,大部分深1000~2000米,由北东北向南西南延长,其南部介于八重山列岛与台湾之间。上述黑潮就在琉球海沟之中,由南向北推进。黑潮和琉球海沟共同成为中国和琉球王国领土的自然疆界。⑦沙学骏:《钓鱼台属中国不属琉球之史地根据》,载于《学粹杂志》1972年第14卷第2期,第17页。自古以来,琉球人在此地带以东生活,中国人在此地带以西生活。综上,由于社会文化因素和地理地质水文等多重因素制约,琉球人无法早于中国先发现钓鱼岛。

(二)中琉之间自古存在天然疆界并有各国史料佐证

中琉之间存在疆界、钓鱼岛属于中国的事实,早已成为中琉两国的共识。从1372年(明洪武五年)至1866年(清同治五年)近500年间,明清两代朝廷先后24次派遣使臣前往琉球王国册封,钓鱼岛是册封使前往琉球的途经之地,有关钓鱼岛的记载大量出现在中国使臣陈侃、谢杰、夏子阳、汪辑、周煌等所撰写的册封使录中。1650年,琉球国相向象贤监修的琉球国第一部正史《中山世鉴》中,全文转载了中国册封使陈侃《使琉球录》所记钓鱼岛列屿内容,其对《使琉球录》中“见古米山(亦称“姑米山”,今久米岛),乃属琉球者”这一中琉地方分界之语并没有提出异议。⑧郑海麟:《钓鱼岛列屿之历史与法理研究》,北京:中华书局2007年版,第98页。此外,1708年,琉球学者、紫金大夫程顺则所著《指南广义》内中附图将钓鱼台、黄尾屿、赤尾屿连为一体,与古米山之间成一明显的分界线。⑨这幅附图,实际上也成为(中国的册封使)陈侃“见古米山,乃属琉球者”及郭汝霖“赤屿者,界琉球地方山也”的最佳注释。参见郑海麟:《钓鱼岛列屿之历史与法理研究》,北京:中华书局2007年版,第98~99页。以上的琉球史料印证了这样的事实:钓鱼岛、赤尾屿属于中国,久米岛属于琉球,分界线在赤尾屿和久米岛间的黑水沟(今冲绳海槽)。日本方面所记载的琉球范围,典型例证如日本林子平(1783-1793)所绘《三国通览图说》(“三国”指虾夷地、朝鲜、琉球)附图中的《琉球三省并三十六岛之图》;⑩林子平所绘《三国通览图说》出版于日本天明五年,即中国乾隆五十年(1785年)秋。《三国通览图说》共有五幅附图,分别是:《三国通览舆地路程全图》、《虾夷国全图》、《朝鲜八道之图》、《无人岛大小之八十余之图》、《琉球三省并三十六岛之图》。参见[日]村田忠禧:《钓鱼岛争议》,载于《百年潮》2004年第6期,第56~62页。琉球方面的历史文献如蔡铎编纂,由其子蔡温年改订的《中山世谱》等都明确记载了琉球的范围。①据《中山世谱》记载,琉球本岛由“三府五州十五郡”(应为三十五郡)组成。所谓“三府”是中头的中山府五州十一郡,“岛尾”的山南府十五郡,“国头”的山北府九郡,另外有三十六岛。参见[日]村田忠禧:《钓鱼岛争议》,载于《百年潮》2004年第6期,第56~62页。从中日琉三国的史料和地图来看,属于琉球的岛屿中,并不包括钓鱼屿、黄尾屿、赤尾屿,这是当时中日琉共同的认识。

(三)日本宣称钓鱼岛为“无主地”的主张既不合史实也不合国际法

日本宣称:“自1885年以来曾多次对尖阁诸岛进行彻底的实地调查,慎重确认尖阁诸岛不仅为无人岛,而且也没有受到清朝统治的痕迹”。②日本外务省:《关于尖阁诸岛所有权问题的基本见解》,下载于http://www.cn.embjapan.go.jp/territory/senkaku/basic_view.html,2016年10月12日。日本政府多年来宣称钓鱼岛是依“无主地先占”原则,透过合法程序编入。在此,日本所称的“多次实地调查”是历史问题,“无主地先占”则是国际法问题。

日本声称自1885年以来,对钓鱼岛“多次”进行“实地调查”,但是这却并非事实。明治时期的官方文件证实,日本仅在1885年10月间对钓鱼岛列屿进行过一次实地调查,而且只登陆了钓鱼岛调查,对黄尾屿、赤尾屿均未登岛调查。③此次调查的结果,体现在石泽兵吾的《鱼钓岛及另外二岛调查概略》和“出云丸号”船长林鹤松的《鱼钓岛、久场、久米赤岛回航报告书》中。二人的报告提交给了代理冲绳县令西村舍三之职的冲绳县大书记官森长义。参见[日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第166~169页;李理:《近代日本对钓鱼岛的非法调查及窃取》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第12~14页。当时的外务大臣井上馨了解到,钓鱼岛列屿是“接近清国国境……台湾近傍之清国所属岛屿”。④《美报文章:日应尊重钓鱼岛相关国际条约》,下载于http://news.xinhuanet.com/ world/2012-10/22/c_123850855.htm,2016年11月1日。外务省“亲展第三十八号”文件表明,井上馨对内文卿山县有朋表达了对建国标事项的反对,称“此时倘公开建立国标,无疑将招致清国猜疑”;⑤“沖縄県久米赤島、久場島、魚釣島ヘ国標建設ノ件”(JCAHR:B03041152300),载于《日本外交文书(第18卷)》,第572页。同年11月24日冲绳县令西村舍三也在公文中证实:“此事与清国不无关系,万一发生矛盾冲突,如何处理至关重要,请予以指示。”⑥B03041152300の17,《日本外交文书(第18卷)》,第576页。1885年11月30日,在太政大臣三条实美给外务大臣井上馨的指令书“秘第二一八号之二”中,最终决定暂缓建设国标。⑦“沖縄県久米赤島、久場島、魚釣島ヘ国標建設ノ件”(JCAHR:B03041152300),载于《日本外交文书(第18卷)》,第572页。佐证上述结论的证据还包括:第一,日本海军省文件表明,1892年1月27日冲绳县县令丸冈莞尔致函海军大臣桦山资纪,鉴于钓鱼岛列屿为“调查未完成”之岛屿,要求海军派遣“海门舰”前往实地调查,但海军省以“季节险恶”为由并未派遣。⑧Han-yi Shaw, The Inconvenient Truth Behind the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, The New York Times, 19 September 2012;台湾“外交部”:《对日本外务省网站有关钓鱼台列屿十六题问与答逐题驳斥全文》,下载于http://www.mofa.gov.tw/cp.aspx?n=FBFB 7416EA72736F&s=FAA8620A0EE72A91,2015年1月30日。第二,1894年5月间,冲绳县县令奈良原繁致函内务省,确认从1885年首次实地调查以来没有再实地调查。⑨“沖縄県久米赤島、久場島、魚釣島ヘ国標建設ノ件”(JCAHR: B03041152300);Han-yi Shaw, The Inconvenient Truth Behind the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, The New York Times, 19 September 2012;台湾“外交部”:《对日本外务省网站有关钓鱼台列屿十六题问与答逐题驳斥全文》,下载于http://www.mofa.gov.tw/cp.aspx?n=FBFB 7416EA72736F&s=FAA8620A0EE72A91,2015年1月30日。至1894年8月中日甲午战争爆发、清国战败之际,1894年12月,日本内务省内务大臣野村靖向外务大臣陆奥宗光发出“密别一三三号”秘密文件,对如何答复一年前冲绳县知事第三次申请建立管辖航标一事进行磋商并称:“业经与贵省磋商后,以指令下达……唯因今昔情况已殊”。⑩“B03041152300の29”,载于《日本外交文书(第18卷)》。这句“唯因今昔情况已殊”充分暴露日本政府趁甲午战争窃我领土的密谋过程,更使日本试图将钓鱼岛和《马关条约》分离的主张难以自圆其说。与冲绳县花费一天时间调查大东岛并设立国标①1885年6-7月,内务省发出密令给冲绳县令西村舍三,指示其调查位于冲绳本岛东部的无人岛大东岛。在西村舍三的命令下,当年8月29日石泽兵吾等人乘“出云丸号”登陆南大东岛,31日登上北大东岛,遵照指令进行实地调查,并建立名为“冲绳县管辖”的国家标志。船长林鹤松建立了题为“奉大日本帝国冲绳县之命东京共同运输公司出云丸创开汽船航路”的航标。“出云丸号”于9月1日返回那霸港。参见[日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第150~152页。相比,日本所称自1885年以来经由冲绳当局等多次对钓鱼台列屿进行实地调查,以及自称钓鱼台列屿是“无主地”等完全不是事实。另外,1885年冲绳县钓鱼岛调查报告——《鱼钓岛及另外二岛调查概略》,②《鱼钓岛及另外二岛调查概略》记载:“此岛与英国出版之日本台湾间海图相对照,相当于Hoa Pin su……海图上以Tia u su标记,实有所误。久米赤岛相当于Raleigh Rock,唯一礁石尔……海图上以Pinnacle为久场岛,亦有所误。Pinnacle一语为顶点之意……故勘其误,鱼钓岛应为Hoa Pin Su,久场岛应为Tia u su,久米赤岛应为Raleigh Rock。”村田忠禧指出,报告的提交者石泽兵吾实际上是误将钓鱼屿认作花瓶屿。参见[日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第169页。也反复提到英国海图中的“Hoa Pin Su”和“Tia u su”,均为中国对钓鱼岛列屿的命名。③郑海麟:《钓鱼岛列屿之历史与法理研究》,北京:中华书局2007年版,第75页。

在国际法中,领土取得的“先占”,是一个国家意图将不属于任何国家主权下的土地,即无主地置于其主权之下的据为己有的行为。④英文“occupation”一词,大陆国际法学家王铁崖领衔翻译的《奥本海国际法》(第9版)中被译为“占领”,台湾国际法学家丘宏达的《现代国际法》(陈纯一修订)在引用《奥本海国际法》同一版本涉及领土争端的部分时,将“occupation”翻译为“先占”。丘宏达认为,“occupation”的翻译在领土取得方面中文译为“先占”,但在战争法上译为“占领”,两者涵义不同。军事占领不能取得主权。本文采用丘宏达的译法。参见丘宏达著,陈纯一修订:《现代国际法(修订第3版)》,台北:三民书局2013年版,第514~515页;[英]詹宁斯、瓦茨修订,王铁崖等译:《奥本海国际法(第一卷,第二分册)》,北京:中国大百科全书出版社1998年版,第74~79页。先占的成立必须确认是以“无主地”⑤“无主地”的概念一度在18世纪的国际法中流行,被欧洲各国用来为殖民行为辩护。18世纪著名国际法学家瓦特尔的《国家间的法律》中阐述了国际法上的“无主地”。他对英国占有大洋洲,或欧洲各国占有整个北美洲的行为进行合理化,将原住民的土地区别为“已垦殖”与“未垦殖”两类。瓦特尔认为,欧洲主导的国际法应当确认人类对于所栖身、使用的土地负有开发、垦殖的义务。那些居无定所的游牧部落失于开发、垦殖土地的义务本身,即意味着可以视他们从未“真正而合法地”占有这些土地;因为这些部落没有成型昭彰的社会组织者,其与土地二者间不得认作国际法上之占有关系,因而其土地为“无主地”,根据发现与先占原则,无主地向所有殖民者敞开。参见De Vattel, Les droit des Gens, ou Principles de la Loi naturelle, appliqués a la conduit at aux af f aires des Nations et des Souverains (1758), translated by Charles为前提,即先占的客体只限于不属于任何国家的土地,这种土地或者完全没有人居住,或者虽然有土著居民,但该土著社会不被认为是一个国家。⑥虽然此原则在现代国际法中还被应用,但国际公认的无主地越来越少,其影响力与认可度也渐渐衰落。先占取得的方式还必须是有效的而不能仅是拟制的。⑦早期国际法并未规定先占必须具备占有和行政管理两个条件,而认为发现就可以主张主权,但19世纪的国际法理论和国家实践均支持先占必须有效才能取得领土主权。⑧

1972年日本外务省《关于尖阁诸岛所有权问题的基本见解》⑨表明,日本政府宣称对钓鱼岛拥有“主权”的“法律依据”不仅有“无主地先占”原则,还声称通过合法程序即1895年1月14日内阁会议决议正式编入日本领土。然而“无人岛”是否即为国际法意义上的“无主地”?日本将钓鱼岛并入其领土的程序是否符合国际法呢?

首先,钓鱼岛列屿虽为无人岛,但是自明代起就被中国官方列入军事海防区域,列入福建的行政管辖范围,这就是一种“有效”占领的方式。冲绳县在19世纪末对包括大东岛在内的无人岛的调查研究表明,日本有很多无人岛。但无人并不意味着没有主人或所有者,必须寻找无人岛的所有者。然而,1885年日本政府便放弃了在钓鱼岛列岛建设国标,是因为已经知道这些岛屿与清国存在关系。那么,如果不向清国询问这些无人岛的主权,并从清国那里得到“不属于清国领土”的答复,日本政府就无法申领所谓的无人岛。⑩事实上日本当时并非不了解国际法“无主地”的确认与占领宣告的原则,例如明治政府于1891年编入硫磺岛时,

Ghequiere Fenwick, Washington: Carnegie institution of Washington, 1916, p. 194.⑥中国大百科全书出版社1998年版,第74页。

⑦ [英]詹宁斯、瓦茨修订,王铁崖等译:《奥本海国际法(第一卷,第二分册)》,北京:中国大百科全书出版社1998年版,第75页。

⑧ Robert Jennings and Arthur Watts, Oppenheim’s International Law, Vol. I, 9th ed., Harlow: Longmans Group UK Limited, 1992, pp. 689~690.

⑨ 日本外务省:《关于尖阁诸岛所有权问题的基本见解》,下载于http://www.cn.embjapan.go.jp/territory/senkaku/basic_view.html,2016年10月12日。

⑩ [日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第150~177页。在1891年8月19日内阁决议后,曾于同年9月9日以勅令第190号公布;之后,明治政府1898年编入南鸟岛时,在1898年7月1日内阁决议后,也于同年7月24日以东京府告示第58号公布。可见日本秘密先占钓鱼岛列屿不但与国际法与国际惯例不符,亦和它自己的国内实践不一致。①台湾“外交部”:《对日本外务省网站有关钓鱼台列屿十六题问与答逐题驳斥全文》,下载于http://www.mofa.gov.tw/cp.aspx?n=FBFB7416EA72736F&s=FAA8620A0 EE72A91,2015年1月30日。

其次,日本称,1896年由冲绳县郡编制的敕令第13号将冲绳县编制成五郡。然而编制中没有提及钓鱼岛及其附属岛屿,也并未将钓鱼岛、黄尾屿等与八重山诸岛并列在一块。也就是说,钓鱼岛、黄尾屿并未被纳入敕令第13号的编制对象。即使在甲午中日战争结束后,日本政府也未对钓鱼岛列岛正式办理领有手续。②[日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第222~223页。被内阁会议批准设置的标桩,实际上冲绳县此后并没有设置。1968年联合国亚洲和远东经济委员会发布了对东海海底资源调查的结论性报告。在此情况下,1969年5月9日,石垣市才匆匆在钓鱼岛上设置了界标。③[日]村田忠禧著,韦平和译:《日中领土争端的起源——从历史档案看钓鱼岛问题》,北京:社会科学文献出版社2013年版,第201~202页。再次,合法的权利,不能源自非法的行为,还有两点可以证明日方主张自始无效:其一是“冲绳县”水产技师(官名)1913年编纂的《宫古郡、八重山郡渔业调查书》。关于“尖阁群岛”,文中提到日本人古贺辰四郎想向日本政府租借,然而由于当时“不无清国所属之说,因此迟迟不见(日本)政府处置。适逢日清战役,依其结果台湾新入我国领土、该岛(尖阁群岛)之领域亦随之明朗。”这透露出明治政府在编入钓鱼岛之前,已知其并非“无主地”。其二是1920年12月9日《官报》第2507号。其中有“所属未定地之编入”与“字名设定”记载二则。“所属未定地”指的是赤尾屿,而新设名称是“大正岛”。这表示1895年1月14日秘密内阁决议,既未合乎日本国内法或国际法,而且在编入范围上有重大疏漏,以至于日本于甲午战争结束25年后,才将赤尾屿片面编入,改名大正岛。④Han-yi Shaw, The Inconvenient Truth Behind the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, The New York Times, 19 September 2012.

综上,先占成立必须确认是以“无主地”为前提。其次,依据文明国家所承认的一般国际法原则,无主地的确认与占领的宣告都是国际法上“无主地”有效先占原则不可或缺的要件。再次,国际法“一国不得以违法作为或不作为取得合法权利或资格”的原则,更充分说明日本窃取钓鱼岛的违法行为不得作为取得合法权利的基础。大量事实证明,日本援引“无主地先占”原则以主张钓鱼岛主权,其依据并不充分。

五、结 论

本文认为,即使在中日“两属”时期,综合考察琉球“近世”时期的历史,并结合19世纪以《万国公法》为代表的近代国际法,琉球仍可以定性为一个主权国家,具体为:

第一,可以从琉球自身的历史,以及与琉球类似的藩属国来考察琉球的历史地位。首先,以时间轴为维度的琉球三个阶段的历史地位,第一阶段即1609年萨摩藩入侵“庆长之役”前,琉球为独立的王国,各国史家争议不大。第二阶段即1609-1872年琉球“两属”时期,琉球王国是否为独立的王国则有争议。这一时期琉球不仅保有自己的政权和年号,与包括日本幕府在内的亚洲周边国家展开外交和贸易交往,1854至1859年间还以现代国际法意义上主权国家的名义与美、法、荷兰三国签订过通商条约,更重要的是,为便于萨摩从中琉贸易中获利,萨摩藩和琉球向包括中国在内的国际社会刻意隐瞒琉萨之间的关系。从中日琉外交关系史和国际法来看,日本并不因萨摩藩的入侵而拥有对琉球的“主权”,因此,不仅琉球“两属”的说法成立,而且琉球为独立王国的说法也成立。第三阶段,即1872-1880年中日琉球交涉时期,琉球的地位悬而未决。该时期中日之间就琉球所属问题频繁的外交交涉、第三国对中日间琉球问题的斡旋,以及1880年中日“分岛改约案”(清政府没有签署),都印证该时期琉球地位为“悬案”的历史事实。其次,在“琉球交涉”前后,清廷和西方列强展开针对另外三个藩属国(朝鲜、越南、缅甸)的外交交涉。与琉球不同的是,清末中国的藩属国越南、朝鲜和缅甸之法律地位的变更,不仅以条约予以确认,而且经过宗主国中国的确认。然而从1879年日本以武力吞并琉球国到二战结束,中日之间除进行过1880年分割琉球条约稿的磋商外,既没有就琉球主权变更、更没有对琉球疆域的安排达成正式协议。更重要的是,这些原为中华朝贡体系的藩属国如今都已摆脱殖民统治,是联合国框架下的独立国家。

第二,基于“时际法”,从近、现代国际法考察琉球的国际法地位。众所周知,近代国际法的代表著作为美国人惠顿的《万国公法》。日清围绕琉球问题进行外交交涉时,“琉球两属”期间的地位问题曾成为双方争议的焦点,《万国公法》成为中日琉三方都曾援引的法律依据。根据《万国公法》的主权、“国际人格者”理论,1609-1879年琉球既为中日“两属”又是独立自主的国家,二者并不矛盾。当然,自1879年被日本吞并、列入版图后,琉球则沦为日本的殖民地,从此琉球的主权遭到减损,这也是不争的事实。1879年日本武力吞并琉球后,“脱清人”和琉球本土的“复国运动”都表明琉球人民的反抗,琉球的宗主国——中国也从未公开承认吞并的合法性。日本自1879年到二战期间对琉球的占领状态,实为国际法领土取得理论中的“征服”,然而这并不能掩盖“琉球法律地位未定”的事实。其次,根据现代国际托管制度,开罗会议中美会谈时曾达成共同托管琉球之共识,而二战后琉球被美国单独实行“事实托管”。此后,美国无视琉球人民独立的意愿,通过《琉球移交协议》把琉球的施政权“返还”给日本,更违反了“国际托管四原则”和托管制度的信托法法理。同时,按照“剩余主权”理论,日本仅取得琉球的施政权而非主权。⑤刘丹:《琉球托管的国际法研究——兼论钓鱼岛的主权归属问题》,载于《太平洋学报》2012年第12期,第82~87页。

总之,从1372年到1879年,作为中国外藩的琉球是国际法意义上的主权国家。1879年日本以武力吞并琉球,遭到琉球人民的反抗,琉球的宗主国——中国也从未公开承认吞并的合法性,琉球法律地位未定有理有据。日本以钓鱼岛隶属于“法律地位未定”的琉球来主张钓鱼岛主权本身就是站不住脚的。

The Japanese government attempted to purchase the Diaoyu Islands in 2012. Since this “farce” staged by the Japanese side concerning the Sino-Japanesedisputes over Diaoyu Islands,①Diaoyu Islands is also called “Diaoyu Dao” or “Diaoyutai” in China, or “Senkaku Islands”in Japan. Except as otherwise stated herein, the term Diaoyu Islands is used throughout this paper to refer to Diaoyu Island and its affiliated islets.the tensions between the two States escalated, and an acrimonious standof f between them still continues. In Chinese academia, especially in Chinese Mainland, few studies have paid enough attention to Ryukyu when examining Japanese claims to the sovereignty over the Diaoyu Islands. The debate on Ryukyu,②In recent years, concerns over the sovereignty of Ryukyu grew quickly in Chinese civil society. Calls for the “restoration of Ryukyu Kingdom” appeared in the internet social media. In Chinese academia, Xu Yong, Tang Chunfeng and other scholars also argue that the status of Ryukyu is uncertain. This argument, frst raised by Taiwanese scholars, rose to prominence in Chinese Mainland around 2012, which sparked the attention of media in Japan and Okinawa. Sino-Japanese relations have become strained after Japan’s move to“nationalize” the Diaoyu Islands. On 8 May 2012, People’s Daily, the official newspaper of China, published an article titled “The Treaty of Shimonoseki and the Diaoyu Dao Issue”, by Zhang Haipeng and Li Guoqiang. This article, in its conclusion, says that “it is the high time to reconsider the pending issue of Ryukyu.” As to the position of Chinese government toward Ryukyu, a Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman asserted, “Chinese government has never changed its position to some relevant issues. The history of Okinawa and Ryukyu is a long-time concern in the academia, which stood up again recently, against the backdrop where the territorial sovereignty of China was jeopardized by Japan’s provocative acts concerning the Diaoyu Islands issue. The articles by scholars reflect the concerns and studies on the Diaoyu Islands and the relevant historical issues by Chinese civil society and academia”.becomes more heated during the tense standof f following the Japanese move to “purchase the Diaoyu Islands” in 2012. The issue of the sovereignty over the Diaoyu Islands is intertwined with the status of the Ryukyu Islands. We should eliminate the misstatements about the status of Ryukyu. In other words, when discussing whether the sovereignty over Ryukyu rests with Japan, if we fortify China’s claims to the Diaoyu Islands from the perspectives of history, geography and international law, and rationally and forcefully refute Japan’s claims based on the subordination of the Diaoyu Islands to Ryukyu③Ministry of Foreign Af f airs of Japan, The Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands, at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/senkaku/basic_view.html, 8 October 2016; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Senkaku Islands Q&A, at http://www.mofa. go.jp/region/asia-paci/senkaku/qa_1010.html, 8 October 2016.with convincible facts, then we can reject Japan’s claims with its own arguments.

I. The History of Ryukyu and Its Relationship with China and Japan

Ryukyu is an ancient kingdom with a long historical and cultural tradition.With its thriving trade, the kingdom was known as a trade transit center in Northeast and Southeast Asia, which earned itself a reputation of “Bridge of Nations”. The geographical boundary of the kingdom is greatly dif f erent from that of today’s Okinawa Prefecture. However, as time goes by, Ryukyuan tributary relations with China is lesser known to the modern generation. Ryukyu was a kingdom having its unique history before 1879, when it was formally annexed by Meiji Japanese government. Ryukyuan history was briefy divided into three times: the primeval, the ancient and the pre-modern times. The primeval Ryukyu includes the old stone age and the shell mound age. The ancient Ryukyu starts with the early 12th century and ends with the invasion of the Ryukyu Kingdom by the Shimazu clan of Satsuma Domain④Satsuma Domain is the local authority controlling the southern Kyushu Island before the Meiji Government replaced its feudal domain system with prefecture system. It is associated with the provinces of Satsuma in the western modern-day Kagoshima Prefecture, Osumi in the eastern modern-day Kagoshima Prefecture and Osumi Islands, and Hyūga in southwestern modern-day Miyazaki Prefecture. After the creation of the Tokugawa regime in the Edo period (1603-1868), this authority became the Satsuma Domain, which was formally named the Kagoshima Domain following the Meiji Restoration. See Sadafumi Fujii and Rokurō Hayashi, Hanshi Jiten, Tokyo: Akita Shoten, 1976, p. 342, quoted from Yuan Jiadong, The Japanese Satsuma Invasion of Ryukyu and the Changes in East Asian Geopolitics, Social Sciences in China, No. 8, 2013, p. 189. (in Chinese)in 1609, spanning 500 years. And the pre-modern Ryukyu covers a period of 270 years, beginning from Satsuma’s invasion of Ryukyu in 1609 until 1879, when the Meiji government abolished the Ryukyu Kingdom and transformed it into the Okinawa Prefecture⑤He Ciyi, The History of the Relations between Ryukyu and Japan in Ming and Qing Dynasties, Nanjing: Jiangsu Ancient Books Publishing House Co. Ltd., 2002, pp. 3~5. (in Chinese)

A. The History of Ryukyu Kingdom and the Tributary Relations between Ryukyu and China

From the unification of the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1429, to the annexation of the kingdom by Japan in 1879, the Ryukyu Kingdom spans two periods, i.e., the ancient and the pre-modern Ryukyu. King Satto became, in 1372, the first Ryukyuan king to submit to Chinese suzerainty. Investiture (cefeng) mission confrmed Satto as king of Chūzan. From 1372 to 1879, when the Ryukyu Kingdom was annexed and transformed into Okinawa Prefecture by Japan, the tributary relations between China and Ryukyu had been maintained for more than 500 years. In all, investiture missions were undertaken 24 times during the Ming and QingDynasties.⑥There is little debate, among the Chinese and Japanese scholars, over the times that the Qing Court sent imperial envoys to Ryukyu. It is generally maintained that the Qing Court sent envoys 8 times to perform investiture ceremony for Ryukyuan kings, involving 16 envoys in all. However, historians failed to reach a consensus over the total times that China dispatched envoys to Ryukyu in the two dynasties of Ming and Qing. It is generally believed to be 24 times, but some scholars also assert that it is 23 times. The main dif f erence lies in their dif f erent views on the times of investiture missions sent in the Ming Dynasty. Xie Bizhen, Wu Shangqing and Akamine Seiki all believe that the Ming Court sent investiture missions 15 times, involving 27 envoys; in contrast, Fang Baochuan asserts that the numbers are 14 (times) and 26 (envoys) respectively. Some scholars contend that the times of investiture missions should be determined on whether the central government has sent envoys to perform investiture ceremony for Ryukyuan King on the land of the kingdom, therefore, the mission carried out by Yang Zai should not be counted, and the Ming and Qing Courts sent envoys 23 times, rather than 24 times to Ryukyu to perform investiture rituals for its kings. See Xie Bizhen and Hu Xin, Historical Data and Research on the History of Sino-Ryukyuan Relations, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2010, pp. 125~126 (in Chinese); Xu Bin, Literati and Officialdom in Ming and Qing Dynasties and Ryukyu, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2011, p. 83. (in Chinese)Ryukyu Kingdom sent more envoys to China.⑦Veritable Records of Emperor Ming Taizu (Vol. 71) stated, the imperial edict that Ming Taizu, also known as the Hongwu Emperor, ordered Yang Zai to carry along to confirm King Satto as king of Chūzan said: “only your country Ryukyu, which is located to the southeast of China and far away in the oversea land, was not informed of the news. Therefore, now I send my envoys to tell you the news.” See Veritable Records of Emperor Ming Taizu, Vol. 71, 16 January 1372 (lunar calendar).Since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two States, upon the accession of a new king after the death of an old king, Chinese envoys would be dispatched to perform investiture ceremonies for the new king, formally acknowledging him as king on behalf of the Chinese Imperial Court. Only after the performance of imperial investitures, can the king officially declare himself to the world as the king of Ryukyu.⑧Xu Bin, Literati and Officialdom in Ming and Qing Dynasties and Ryukyu, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2011, p. 36. (in Chinese)Historical descriptions of the Diaoyu Islands can mostly be found in the detailed written reports submitted by the envoys to the Ming and Qing Emperors about their journeys upon return to China.

B. Issue concerning Ryukyu’s Dual Subordination to China and Japan

in the Context of Multilateral Relationship among the Three States

The period between 1609 (the year Ryukyu was invaded by the Satsuma Domain) and 1879 (the year that the Ryukyu Domain was abolished and transformed into a prefecture by the Meiji Government), is called “a period of dual subordination” in Ryukyuan history by historians. In 1609, the Shimazu clanof the Satsuma Domain dispatched troops to invade Ryukyu, and Ryukyuan King Shō Nei and his councilors were taken prisoner. This battle is known to history as“Satsuma Invasion of Ryukyu 1609”. After the battle, Ryukyu was subordinated to China nominally but to Japan technically and secretly.⑨Zheng Hailin, The History of Diaoyu Islands and the Relevant Jurisprudence (Revised and Enlarged Edition), Hong Kong: Ming Pao Publications Ltd., 2011, p. 124. (in Chinese)This situation continued to the early years of Meiji Restoration. In the Chinese Qing Dynasty, the late Second Shō Dynasty of Ryukyu began, during which Ryukyu requested Chinese Qing Court for investiture. Shô Hô, then known as Prince Sashiki Chôshô, fled petitions to Chinese Imperial Court for investiture in 1625, 1626 and 1627 respectively. Such petitions were made under the secret control of Satsuma Domain after the“Satsuma Invasion of Ryukyu 1609”.⑩Xu Bin, Literati and Officialdom in Ming and Qing Dynasties and Ryukyu, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2011, p. 4. (in Chinese)Thereafter, constantly pushed by Satsuma Domain, Ryukyu restored its tributary and trade relations with China in 1633. In September 1872, the Meiji Emperor issued an imperial decree, granting the royal linage of Ryukyu the title “seignior, and included them in the kazoku of Japan”.①Mi Qingyu, A Research on Ryukyuan History, Tianjin: Tianjin People’s Publishing House, 1998, pp. 112~114. (in Chinese)This decree set the stage for Japan’s annexation of Ryukyu, which was formally annexed by Japan in 1879. The facts mentioned above explain the origin of the dual subordination of Ryukyu.

Following the Satsuma invasion of Ryukyu, Satsuma controlled the kingdom politically and economically. However, in order to gain benefts from the tributary and trade relations between Ryukyu and China, Satsuma made great efforts to obscure its domination of Ryukyu from the Chinese Court. The measures Satsuma took in this regard include: a). to forbid Ryukyu from adopting Japanese system, and the Ryukyuans from adopting Japanese names, so that Chinese envoys would not discover the real relations between Satsuma and Ryukyu. For example, Ji Kao (A Research) said that, on 20 August 1624, the premier (the Satsuma Domain internally called itself a State) was appointed to serve in Ryukyu according to an imperial decree; thereafter, Ryukyuan hierarchical court system and criminal law and policies would be decided by the Ryukyu king himself; Ryukyuans were forbidden from adopting Japanese names, clothes, or customs.②Yang Chungkui, Ancient and Modern Ryukyu, and the Issue of Diaoyutai, Taipei: The Commercial Press, Ltd., 1990, pp. 64~65. (in Chinese)b). During the stay of Chinese envoys in Ryukyu, for the sake of hiding truths from Chinese envoys,Satsuma required all Japanese officials residing in Ryukyu, including zaibanbugyou and yamatoyokome, if not properly camoufaged, to move to some remote places on east coast of Ryukyu, which were far away from the west coastal areas frequented by Chinese; also, Satsuma banned all posters and shop signs written in Japanese; moreover, it required all books, records and reports not to mention the relationship between Japan and Ryukyu in the “Satsuma Invasion of Ryukyu 1609”.③Yang Chungkui, Ancient and Modern Ryukyu, and the Issue of Diaoyutai, Taipei: The Commercial Press, Ltd., 1990, pp. 64~65. (in Chinese)c. The authorities of Ryukyu compiled and published some books or documents, which included, among others, Questions & Answers about Ryukyu and Experiences of a Traveler. Questions & Answers about Ryukyu is a list of questions and answers developed under the auspice of the king residing in Shuri, with an aim to prevent the “Ryukyuan castaways”④Ryukyuan castaways incidents: since the establishment of tributary relations between China and Ryukyu in the Ming Dynasty, 12 Ryukyuan ships or ships used for tribute missions had been wrecked and wandered into the coastal areas of China. Both the Qing and Ming Courts had the practice of salvaging and resettling the castaways, including those from Ryukyu, granting pensions to them, and sending them back to their home countries. Such practices formed a sino-centric marine salvage mechanism, with participation from its tributary and non-tributary States (such as Japan). Since the shipwrecks were caused mainly by the miscalculation of the monsoon season, in the period of dual subordination, Shuri Royal Government ordered its subjects to strictly follow the right time to leave or return to its ports. Even in that case, shipwreck incidents still happened. See Lai Zhengwei, A Research on the Sino-Ryukyuan Relations in the Qing Dynasty, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2011, pp. 56~60 (in Chinese); [Japan] Murata Tadayoshi, The Origin of Sino-Japanese Territorial Disputes: the Diaoyu Islands Issue Seen from Historical Archives, translated by Wei Pinghe, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (China), 2013, p. 52. (in Chinese)from telling Satsuma’s technical control of Ryukyu. In this list, the first question is about the territory ruled by the Ryukyuan king. The answer given to this question is: “the territory includes three principalities: Chūzan, Nanzan and Hokuzan, and 36 islands, including Yaeyama and Yonagunijima islands in the south, Amami-Ōshima and Kikaigashima in the north, Kume Island in the west, and Ikei and Tsuken Islands in the east”. However, at that time, Amami-Ōshima and Kikaigashima were actually under the jurisdiction of Satsuma Domain. Obviously, it deliberately concealed this situation from the Chinese Qing Court.⑤[Japan] Murata Tadayoshi, The Origin of Sino-Japanese Territorial Disputes: the Diaoyu Islands Issue Seen from Historical Archives, translated by Wei Pinghe, Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (China), 2013, pp. 52~53. (in Chinese)Experiences of a Traveler, published in 1759, is a pamphlet by a Chinese-Ryukyuan politician named Cai Wen, which is full of standard answers to questions regarding China and Ryukyu. It aims to tell the Ryukyuan officials, students whose fathers are officials, and ordinary businessmen in China how to reply to questionsthat Chinese people may raise, most importantly, the questions concerning the relationship between Satsuma and Ryukyu.⑥Yang Chungkui, Ancient and Modern Ryukyu, and the Issue of Diaoyutai, Taipei: The Commercial Press, Ltd., 1990, pp. 64~65. (in Chinese)

II. The Status of a Vassal State in International Law: A Perspective from Elements of International Law

The Asian tributary system was a China-centered international structure featured by suzerain-vassal relations between China and its neighbors. The system of the law of nations, also known as the treaty system, is an international system based on the international order in the world upholding the law of nations, which is a network of treaty relations dominated by the Western colonial powers shaped during the colonial expansion in modern times.⑦The term “treaty system”, which coexisted with the tributary system in late Qing Dynasty, was proposed by Fairbank. See J. K. Fairbank, The Early Treaty System in the Chinese World Order, in J. K. Fairbank ed., The Chinese World Order: Traditional China’s Foreign Relations, Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press, 1969, pp. 257~275.Western modern international law was first formally and systematically introduced into China in the 19th century. However, in the late 19th century, when Vietnam, Burma, Korea and other vassal States of Qing Court turned into colonies and protectorate of occidental powers and Japan, the tributary system disbanded.

A. The Introduction of Elements of International Law into China and Its Inf l uences on the Diplomacy of Qing Government

As mentioned above, Western modern international law was first formally and systematically introduced into China in the 19th century. The Chinese edition of Elements of International Law,⑧The Chinese version of Elements of International Law (named “万国公法” in Chinese) is translated by William A. P. Martin (1827-1916), an American missionary, from its English version, which was published by the American publicist Henry Wheaton (1785-1848) in 1836. This Chinese version was printed by Beijing Chongshi School in the winter of 1864. See Lin Xuezhong, From Elements of International Law to Diplomacy Based on International Law: the Reception, Interpretation, and Application of International Law in the Late Qing, Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2009, p. 113. (in Chinese)which was translated by William A. P. Martin (1827-1916), an American missionary to China, was the first work on Western jurisprudence in Chinese history. When frst published in China, the book causeda stir in the East Asia. In the following year, recarved and kunten-marked editions appeared in Japan, which became one of Japanese bestsellers in a short time. Subsequent editions also appeared in Korea and Vietnam.19 In the early⑨Zou Zhenhuan, A Comparative Study on the Distribution of the Elements of International Law Translated by W. A. P. Martin in China, Japan and Korea, in Center for South Korea Studies of Fudan University ed., South Korea Studies, Vol. 7, Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 2000, pp. 258~278. (in Chinese)th century, China became a country occidental powers plotted to colonize in East Asia. China was afterwards drawn into the Opium Wars. In 1901 when the Boxer Protocol was signed, China completely turned into a semi-colonial and semi-feudal country. Against this backdrop, the attitudes towards the introduction of Western international law into China are sometimes contradictory among different social strata in China. On one hand, cases really existed where the Qing Government won in diplomatic negotiations against Western countries by applying international law, such as Lin Zexu’s prohibition of the sale of opium⑩Mao Haijian, Collapse of the Celestial Empire: A Re-examination on the Opium Wars, Beijing: Joint Publishing, 1995, pp. 104~112. (in Chinese)and the handling of Lin Weixi Case①In July 1839, a local named Lin Weixi in the village of Tsim Sha Tsui was beaten to death by a British sailor. For research on this incident, see Lam Kai-yin and Lam Kam-yuen, On the Approaches and Attitudes of the Chinese and British Governments in Dealing with the Lin Weixi Incident, Historical Research, No. 2, 2000, pp. 97~113. (in Chinese)in 1839, and the settlement of the dispute concerning Prussia’s seizure of Danish ships in Chinese territorial sea;②In April 1864, when the Prussian minister H. Von Rehfues came to China by the warship Gazelle, he, without causes, captured three Danish commercial ships in the waters of Dagu Port, Tianjin, China. Zongli Yamen (Ministry of Foreign Af f airs) of Qing China protested against Prussia’s act immediately, by invoking international legal concepts. The Prussian minister was accused of capturing Danish ships in Chinese “inner ocean” (or “territorial sea”), over which China had jurisdiction. The Prussians were further informed that should the ships not be released then China could refuse a reception to their officials. Ultimately, Prussia released two of the captured ships, and paid a compensation at the amount of $1500. This incident was thus settled peacefully. For the details of this incident and the invocation of international law by Qing Court, see Wang Weijian, Prussian-Danish Incident in Dagu Port and the Introduction of Western International Law into China, Academic Research, No. 5, 1985, pp. 84~90. (in Chinese)to some extent, the successful resolution of these diplomatic disputes led to Qing Government’s quick approval of the printing of Elements of International Law. On the other hand, Qing Government and its officials inclined to use international law as an instrument, seeking to invoke relevant rules to defeat foreigners in diplomatic negotiations.

The international community, in the wake of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), has its unique connotation. This community, also called an “international law community” or “civilized community”, is a Euro-centric binding system

of rules of modern international law, which is composed of European sovereign States, reflecting Western values. Kikoh Nishizato, a historian with University of the Ryukyus, stated that the modern East Asia has undergone an era where the relationship between the East Asian States and nations and occidental powers was reversed, and also an era where the traditional international system in East Asia, i.e., the tributary system, was replaced by the modern international order dominated by the occidental powers, which was also known as the system of the law of nations.③[Japan] Kikoh Nishizato, A Study on the History of Relations between Ryukyu and Japan in the Late Qing Dynasty (I), translated by Hu Liancheng et al., Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (China), 2010, p. 17. (in Chinese)Chinese professor Wang Hui contended that, the conficts between Chinese Qing Court and European powers were not ordinary inter-State conflicts, but rather those between two world (or international) systems and their rules.④Wang Hui, The Rise of Modern Chinese Thoughts, Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2004, p. 680. (in Chinese)Here, the two systems refer to the tributary system and the modern system of the law of nations respectively. In the latter system, the world was divided into civilized, partially civilized, barbarous and savage States (Table 1). Being considered as “barbarous States”, China and other Asian States were not full legal persons as States, where only partial principles of international law could be applied. Such dif f erentiation of States rights under this international order can be best explained by those unequal treaties, whose principal provisions include unilateral most-favoured-nation treatment, consular jurisdiction and agreement tariff. Such an international order is utterly based on Euro-centrism. However, in the political arena in the late 19th century and the early 20th century, everything was staged exactly under this kind of prejudice.⑤Lin Xuezhong, From Elements of International Law to Diplomacy Based on International Law: the Reception, Interpretation, and Application of International Law in the Late Qing, Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2009, p. 243. (in Chinese)

Table 1 The International Order in the World Upholding the Law of Nations in the Late 19th Century26

B. Tributary/Vassal States Def i ned in the Elements of International Law

A comparison of two masterpieces in international law - Elements of International Law written in the 19th century and Oppenheim’s International Law⑦Oppenheim’s International Law is considered as another internationally renowned book, following the Elements of International Law, in the 20th century. This book fnds its early form in the two volumes of International Law: A Treatise initially published in 1905-1906, by the internationalist L. F. L. Oppenheim (1858-1919). This work won him enough prestige to be appointed as the Whewell Professor of International Law in the University of Cambridge. The second edition of the book was revised by Oppenheim himself. Oppenheim’s International Law was afterwards edited by Ronald Francis Roxburgh, Arnold Duncan McNair, Hersch Lauterpacht and other renowned scholars of international law, and is known as a “Cambridge Monograph”. Robert Jennings and Arthur Watts eds., Oppenheim’s International Law, Vol. 1, No. 1, translated by Wang Tieya et al., Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House, 1998, pp. III~V. (in Chinese)in the 20th century, shows that “colony” is one category of the “international persons”in modern international law. The international law concepts closely related to the tributary system, such as “protectorate”, “half sovereign State” and “tributary State”, were discussed in the chapter “Nations and Sovereign States” under the Elements of International Law. An “international person”, in the modern international law, is one who possesses legal personality in international law, meaning one who is a subject of international law so as itself to enjoy rights, duties or powers established in international law.⑧Robert Jennings and Arthur Watts eds., Oppenheim’s International Law, Vol. 1, No. 1, translated by Wang Tieya et al., Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House, 1998, p. 90. (in Chinese)An analysis of the meaning and evolutions of the concept “international person” in modern international law would provides some important insights into the discussion on the status of Ryukyu in modern international law. With regards to the status of Ryukyu, authorities have invoked and applied the principles, rules and theories embodied in the Elements of International Law in the diplomatic negotiations between China, Japan and Ryukyu.

In order to understand the categories and meaning of international persons in the 19th century, we need to trace the concept back to its origin - Elements ofInternational Law. From its Chinese edition translated by William A. P. Martin⑨It is noteworthy that, Prof. He Qinhua, the proofreader of the Chinese version of Elements of International Law (Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2003) stated, William A. P. Martin’s translation was abridged and adjusted from the original work, with some contents deleted and its structure, style or chapters adjusted. For example, nearly 90% of original words of Volume 1, Chapter 2, Section 23 (titled “Germanic Confederation”) were deleted by William in his translation, only retaining a summary. Additionally, subject to the historical conditions and the translator’s Chinese profciency, the Chinese version is fraught with translation errors. See Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, translated by William A. P. Martin, proofread by He Qinhua, Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2003, Preface by Proofreader, p. 51 (in Chinese). By virtue of it, the paper pays a special attention to the dif f erence between the Chinese and English versions, particularly those parts deleted or omitted in the Chinese version.and the eighth English edition published by Little, Brown and Company, a publisher based on Boston, in 1866,⑩The National Library of China collected several editions of Elements of International Law in its House of Foreign Literature. This book has been reprinted many times since its frst publication in 1836. The main contents of this book remained unchanged, but with notes or international conventions added by editors as appendix. The author referred to the 8th edition published in Boston in 1866, edited with notes, by Richard Henry Dana. See Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, p. viii.we can find that Wheaton’s Elements of International Law①William A. P. Martin’s translation of Elements of International Law was published in 1864 by Beijing Chongshi School. This Chinese edition is translated from the 6th edition of Elements of International Law: With a Sketch of the History of the Science, which was edited with notes by William Beach Lawrence (1800-1881) (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1855). See Lin Xuezhong, From Elements of International Law to Diplomacy Based on International Law: the Reception, Interpretation, and Application of International Law in the Late Qing, Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2009, p. 113. (in Chinese)mentioned, in Volume I, Chapter II, “State”, “semi-sovereign State”, “protectorate”, “vassal State” and other categories enjoying full or partial international personality. Particularly, the discussion on the sovereignty of a vassal State in this book deserves our attention.

Quoting the words of Cicero, Elements of International Law defined “a State to be, a body of politic, or society of men, united together for the purpose of promoting their mutual safety and advantage by their combined strength.” In order to explain the requisite of a State, Wheaton added, “the legal idea of a State necessarily implies that of the habitual obedience of its members to those persons in whom the superiority is vested, and of a fixed abode, and definite territorybelonging to the people by whom it is occupied.”②Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, translated by William A. P. Martin, proofread by He Qinhua, Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2003, pp. 25~26. (in Chinese)In the international law of the 19th century, the indispensible requisites of a State include persons of fxed abode, defnite territory and borders,③Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, p. 22.which are much easier to meet than those requisites set in modern international law. Elements of International Law divided States into sovereign and semi-sovereign ones. A sovereign State means “a community or a number of persons permanently organized under a sovereign government of their own, and by a sovereign government we mean a government, however constituted, which exercises the power of making and enforcing law within a community, and is not itself subject to any superior government.”④Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, translated by William A. P. Martin, proofread by He Qinhua, Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2003, p. 37. (in Chinese)And semi-sovereign States were termed as “States which are thus dependent on other States, in respect to the exercise of certain rights, essential to the perfect external sovereignty”. In addition to the United States of the Ionian Islands and Cracow, which were prescribed as “semi-sovereign States” by treaties, protectorate or dependent States also fell under this category.⑤Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, pp. 45~46.Sovereignty may be exercised either internally or externally.“internal sovereignty is that which is inherent in the people of any State, or vested in its ruler, by its municipal constitution or fundamental laws … External sovereignty consists in the independence of one political society, in respect to all other political societies. It is by the exercise of this branch of sovereignty that the international relations of one political society are maintained, in peace and in war, with all other political societies.”⑥Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, translated by William A. P. Martin, proofread by He Qinhua, Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2003, pp. 35~36. (in Chinese)

Elements of International Law contains a section entitled “Tributary States”.⑦Section 37, Chapter 2 of Wheaton’s Elements of International Law is entitled “Tributary States”, see Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, pp. 48~49.In the eye of international law, the autonomy of a tributary or vassal State dependson the sovereignty it enjoyed.⑧Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, translated by William A. P. Martin, proofread by He Qinhua, Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2003, p. 41. (in Chinese)That is to say, tributary States are still considered as sovereign, as far as their sovereignty is not affected by the tribute. Wheaton illustrated some categories of tributaries:⑨Henry Wheaton, Elements of International Law, translated by William A. P. Martin, proofread by He Qinhua, Beijing: China University of Political Science and Law Press, 2003, pp. 41~42. (in Chinese)First, the tribute, formerly paid by the principal maritime powers of Europe to Barbary, did not at all af f ect the sovereignty and independence of the former; Second, “the King of Naples had been a nominal vassal of the Papal See, ever since the eleventh century, but this feudal dependence, abolished in 1818, was never considered as impairing the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Naples.”⑩Wheaton, Elements of International Law, edited, with notes, by Richard Henry Dana, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866, p. 49.

C. Diplomacy Based on International Law that Qing Court Used to Defend Its Vassal States - Korea, Burma and Vietnam

The tributary system, as an important constituent of the political structure of ancient China, traces its roots to the Han Dynasty. The Tang Dynasty continued this system while making some innovations, by establishing Jimo Prefectures, another kind of vassal, in its border areas inhabited by minority nationalities. Following the tributary system of the Tang and Yuan Dynasties, the Ming Dynasty also devised some new measures to improve the system. And the system fourished in the Qing Dynasty①Huang Songyun, Theoretic Problems in the Study of Chinese Tributary System, Social Science Front, No. 6, 2004, p. 121. (in Chinese)The economic exchanges between the suzerain and tributary States were primarily conducted through tributes paying, gifting, and tributarytrades. The tributary system is termed by John King Fairbank②John King Fairbank has done some pioneering researches on the Sino-centrist worldview, which is the theoretic basis of Chinese tributary system, as well as on the characteristics of the tributary system which merge politics, trade and diplomacy into its network. Plus, he also studied the trend of modern China with his impact-response model. Many concepts advanced by scholars afterwards, such as “Huayi Order”, “Chinese Confucian system”,“Chinese world order” and “East Asian world order”, are considered as related to ancient China’s foreign relations, diplomatic institutions and thoughts, which, however, are all associated with Chinese tributary system. Fairbank’s views above described the structure of the tributary system. Yet, it should be noted, inner Asian Nomads were greatly dif f erent from the tributary States within the Chinese culture circle, albeit in the same tributary system. Siam, Burma and other tributaries also varied from European States, which cannot be put under the same category, because the former States maintained an official tributary relations with China. See Wang Peipei, Tributary and Treaty Systems, Social Sciences Review, Vol. 26, No. 8, 2011, pp. 115~117. (in Chinese)as a graded and concentric hierarchy of foreign relations with peoples and States grouped in three main zones: firstly, the Sinic Zone, consisting of the most nearby and culturally similar territories, including Korea, Vietnam, Ryukyu Islands and, at brief times, Japan; secondly, the Inner Asia Zone, consisting of tributary tribes and States of the nomadic or semi-nomadic peoples of Inner Asia; thirdly, the Outer Zone, consisting of the “Outer barbarians”, generally at a farther distance over land or sea, including Japan, some Southeast and South Asian States and Europe.③John King Fairbank ed., The Chinese World Order, Traditional China’s Foreign Relations, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968, p. 2.The Qing Court roughly classifed foreign States into two groups: one is “tributaries” (see Table 2), which are States having formal diplomatic relations with China, including Korea, Ryukyu, Annam (today’s Vietnam), Siam (today’s Thailand), Burma, Laos and Sulu (Sulu Archipelago in today’s Philippines); the other group is States that traded with China but had no formal diplomatic relations, including Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, the UK, France and other European States.④Li Yunquan, The History of Tributary System: A Study on Institutions Related to the Foreign Relations of Ancient China, Beijing: Xinhua Press, 2004, pp. 134~148. (in Chinese)

Table 2 Timetable for Chinese Main Tributaries in the Qing Dynasty to First Pay Tributes and Receive Investiture45

Siam16641673 Sulu1726 Loas17301795 Burma17501790

Diplomatic af f airs that the Qing Government had to handle with its tributary States, are not limited to the status of the latter; they are also closely related to complex issues like international treaties, rules of engagement, law of neutrality, customary international law and territorial boundaries of States, which this paper is not able to exhaust. Nevertheless, the status of tributary States is an issue that the Qing Government has to deal with in its diplomatic negotiations. When it comes to the issues like whether Korea, Vietnam, Burma and other tributaries were autonomous on their own, and how to protect or support them, Qing’s actual approaches to these issues deviated a bit from its diplomatic policy.

Among the tributaries of China, Korea was called a “junior Middle-Kingdom”. In order to maintain their suzerain-vassal relation, Qing provided omnibearing protection to Korea. It not only send troops to Korea, but also directly interfered with its internal and foreign af f airs at the cost of changing the traditional approach, and reinforced its suzerainty over Korea by applying international law and the treaty system. Even after the signing of the Convention of Tientsin, also known as the Tianjin Convention, in 1885, Qing did not recognize Korea as a sovereign State. In the aftermath of Ganghwa Island Incident started by the Japanese in 1876, following the traditions of “balance-of-power” diplomacy, Qing encouraged Korea to open fre with Europe and America, struggling to maintain its suzerainty over Korea by building a balance of power there. Being aware that the tenets underpinning traditional Chinese world order was unable to maintain Sino-Korean relationship any more, Qing changed its diplomatic strategies, even attempting to continue their suzerainty-vassal relationship through the application of rules of international law. After the Imo Incident in 1882, Qing recognized Korea’s autonomy in form, but in substance, Qing started to interfered with its internal and foreign af f airs; additionally, Qing concluded the Sino-Korean Commercial Treaty with Korea in October 1882, proclaiming its traditional suzerainty over Korea in writing under the treaty system.⑥Lin Xuezhong, From Elements of International Law to Diplomacy Based on International Law: the Reception, Interpretation, and Application of International Law in the Late Qing, Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2009, pp. 276~278. (in Chinese)

Adhering to the border security idea of “protecting China’s tributaries to consolidate its own borders”,⑦Ma Dazheng ed., An Outlined History of Chinese Borders/Book Series on the General History of China’s Borders, Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House, 2000, p. 398. (in Chinese)Qing dispatched troops to aid Vietnam, trying to keep its enemy from the gates, but with no intention to have any direct confict with France initially. France annexed Vietnam mainly through diplomatic negotiations and conclusion of treaties, during which it also destroyed many evidences supporting China’s suzerainty over Vietnam. First, France asserted, in accordance with the tributary system in Western international law, “if a State is superior to another, then the former should decide and manage all the government and administrative af f airs for and on behalf the latter”, therefore China had no effective jurisdiction over Vietnam.⑧Kuo Ting-yee et al. eds., Archives on Sino-French Negotiations over the Vietnam Issue (II), Taipei: Institute of Modern History, “Academia Sinica”, 1962, p. 927. (in Chinese)Subsequently, France required China to remain neutral, as a third State, in the wars against Vietnam.⑨For example, Li Hongzhang, in June 1883, received a letter from France, which said:“Currently, France and Vietnam are at war, which, in accordance with international law, any third States should not intervene, therefore, we should discuss the matter after a ceasefre between France and Vietnam.” Kuo Ting-yee et al. eds., Archives on Sino-French Negotiations over the Vietnam Issue (II), Taipei: Institute of Modern History, “Academia Sinica”, 1962, p. 910. (in Chinese)Second, it used a series of treaties, including Tientsin Accord, concluded on 11 May 1884 between France and China, and the Treaty of Hue, concluded on 6 June 1884 between France and Annam (Vietnam), to gradually effect the change of Vietnam from a “sovereign State” to a French protectorate. Particularly, before the execution and exchange of text of the Treaty of Hue, Jules Patenôtre, the French minister to China, coerced the Nguyen Dynasty to turn in the gold plated seal presented by the Qing Emperor several decades earlier to the Vietnamese king, which was then melted down,⑩Zhang Denggui et al. eds., Đai Nam Thuc Luc, Tokyo: Keio University, 1961-1981, p. 4, quoted from Li Yunquan, Sino-French Negotiations over the Vietnam Issue before the Sino-French War and the Change of Sino-Vietnamese Relations, Social Science Journal, No. 5, 2010, p. 155. (in Chinese)so as to permanently destroy the proof evidencing China’s suzerainty over Vietnam. In this regard, one comment says, “resembling those negotiations between China and Japan over the tributary status of Korea, the negotiations between China and France over the tributary status of Vietnam are doomed to be a fruitless tug-of-war.”①Li Yunquan, Sino-French Negotiations over the Vietnam Issue before the Sino-French War and the Change of Sino-Vietnamese Relations, Social Science Journal, No. 5, 2010, p. 151. (in Chinese)

Burma’s official relation with China was not established until the mid-18th century. In response to UK’s question towards the tributary status of Burma, Marquis Zeng Jize, China’s minister to Britain, denied UK’s claims and demonstrated that Burma was tributary to China based on sound grounds and tangible evidences. The British government claimed that the treaty concluded between China and Burma in 1770 was an equal treaty between the two; Marquis Zeng refuted this claim, pointing out that the treaty was only a declaration of surrender to China made by Burma.②The text of the telegraph reads: “The Seal of Burma King was presented in 1790. The writing style of the characters on the seal was Shangfang Dazhuan (one type of greater seal scripts in ancient China) in the languages of Han and Manchu. The seal is made of silver and has a camel-shaped golden handle. The base of the seal is 3.5 * 3.5 Chinese cun (1 cun = 31⁄3cm) and 1 Chinese cun thick. And the words on the seal reads ‘Seal of Burma King in Mandalay’.” See He Xinhua, An Analysis on the Tributary Status of Burma in Qing Dynasty, Historical Archives, No. 1, 2006, p. 75. (in Chinese)And he had received a telegraph from Zongli Yamen (Ministry of Foreign Af f airs) of Qing China, informing him of the size, font and content of the seal that the Qing Emperor presented to the Burma King.③Wang Yanwei, Historical Documents on Qing’s Foreign Relations (Vol. 61), Beijing: The Palace Museum, 1932, p. 29. (in Chinese)The UK also proposed that Burma, in the process of their conficts, failed to raise any request for protection from Qing Court. Qing explained it by saying that Burma violated its obligations as a tributary,④He Xinhua, An Analysis on the Tributary Status of Burma in Qing Dynasty, Historical Archives, No. 1, 2006, p. 75. (in Chinese)but did not, in substance, intervene in British occupation of Burma, which indicated that Qing adopted a pragmatist approach to deal with its relations with Burma. In the late 18th and early 19th century, Siam, Burma’s southern neighbor, grew in power and brought huge threats to Burma. Afterwards, the UK invaded into the southern and western Burma. Under this context, Burma frequently sent tributes to China exactly in this period. In practice, Burma maintained an “ambiguous attitude”⑤Burma’ ambiguous attitude can be detected from Burma King’s attitude towards the seal presented by Qianlong Emperor in 1790. When “Chinese envoys carried the camel-shaped seal signifying Burma’s subordination to China, the Burma King, fearing to be controlled by Qing Court, was initially reluctant to accept the seal. However, he was also unwilling to reject such a piece of gold weighing 3 peittha (10 lb), eventually he decided to accept it, but ordering his court recorder not to recount this matter.” G. E. Harvey, History of Burma (Vol. 2), translated by Yao Ziliang, Beijing: The Commercial Press, 1973, p. 453. (in Chinese)towards its tributary status; it neither treated China as a “Middle Kingdom”, nor proactively acknowledged its tributary relation with China.⑥He Xinhua, An Analysis on the Tributary Status of Burma in Qing Dynasty, Historical Archives, No. 1, 2006, p. 72. (in Chinese)

In the middle and late 19th century, “British invasion of Burma, French invasion of Vietnam and Japanese invasion of Ryukyu, were all started by the foreign sides. Caught in troubled times, China struggled to rise from the ashes, but beyond its strength.”⑦Lu Fengshi, Veritable Records of Qing Emperor De Zong (Vol. 232, September 1886), Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1987. (in Chinese)Qing was eventually defeated in the First Sino-Japanese War by the end of the 19th century. After the collapse of the tributary system, China was forced to abandon its idea of Middle Kingdom, and to accept Western values based on the system of the law of nations.

III. The Historical and International Law Status of Pre-modern Ryukyu Viewed from Sino-Japanese Negotiations concerning Ryukyu