草间弥生:圆点女王的世界

2016-03-04ByDavidPilling

By+David+Pilling

如果你一定要问我从什么时候开始艺术创作的,我可以告诉你,那是在很小很小的时候。我的一生,我活着的每一个日子,都与艺术相关。要是人可以有来世,我还想再做艺术家。无论生与死,艺术对于我来说就是一切。

—— 草间弥生(日本艺术家)

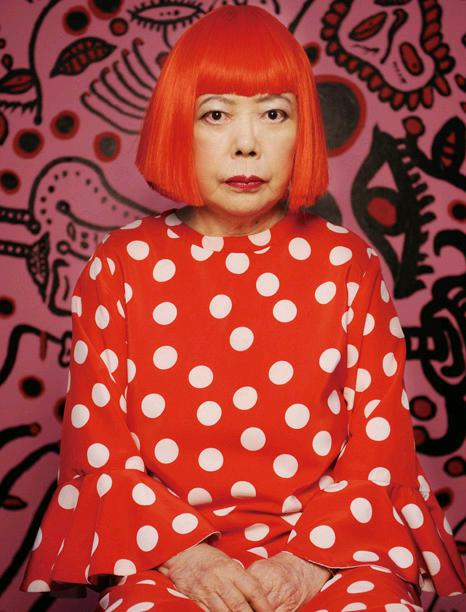

Yayoi Kusama is 87 years old. But when she is wheeled in, on her blue polka-dotted wheelchair, she looks more like a baby, the sort you might see played by an adult in a British pantomime1). Her face is large for a Japanese woman and at odds2) with her smallish frame. Apart from her intense, saucer-shaped eyes and the arc of deep red lipstick across her mouth, there is something masculine about her features. She wears a lurid red wig and a dress covered in polka dots. Coiled around her neck is a long red scarf decorated with black squiggles. When she is out of the spotlight, without her splashy red wig and garish outfits, she looks like a nice, grey-haired old lady. It is as if the patterns she has obsessively replicated since childhood have seeped off the canvas and into the three-dimensional world of flesh and blood.

Kusamas story begins in the conservative surroundings of rural Japan in 1929, where she was born in Matsumoto, Nagano prefecture3), into a family of seedling merchants. One early photo, taken at the age of about 10, shows a serious, rather beautiful girl with short hair, holding an enormous bunch of chrysanthemums4). So upstanding was her mothers family, that her father, a philanderer5) who spent much of his time in the company of geisha6), adopted the Kusama name as his own. At around the time the photograph was taken, Kusama was already producing pencil sketches featuring dots and a net-like motif. Even a portrait of her mother, whom she hated for her strictness and prudish7) values, is covered in dots as though she were suffering from chicken pox. “My parents were a real pain,” she says. “I couldnt stand it. They were very conservative. My family had been running the business for 100 years. My parents had old customs and morals.”

From early childhood Kusama experienced “visual and aural hallucinations8).” In her autobiography, she writes of her experience sitting among a bed of violets. “One day, I suddenly looked up to find that each and every violet had its own individual, human-like facial expression, and to my astonishment they were all talking to me.” On other occasions, “suddenly things would be flashing and glittering all around me. So many different images leaped into my eyes that I was left dazzled and dumbfounded.” Whenever these hallucinations occurred, she would rush home and draw what she had seen.

In 1948, after the war had ended, she began a formal course in Kyoto where she was instructed in Nihonga9), a style of Japanese painting. She hated the rigidities of the master-disciple system where students were supposed to imbibe10) tradition through the sensei11). “When I think of my life in Kyoto,” she says, “I feel like vomiting.”

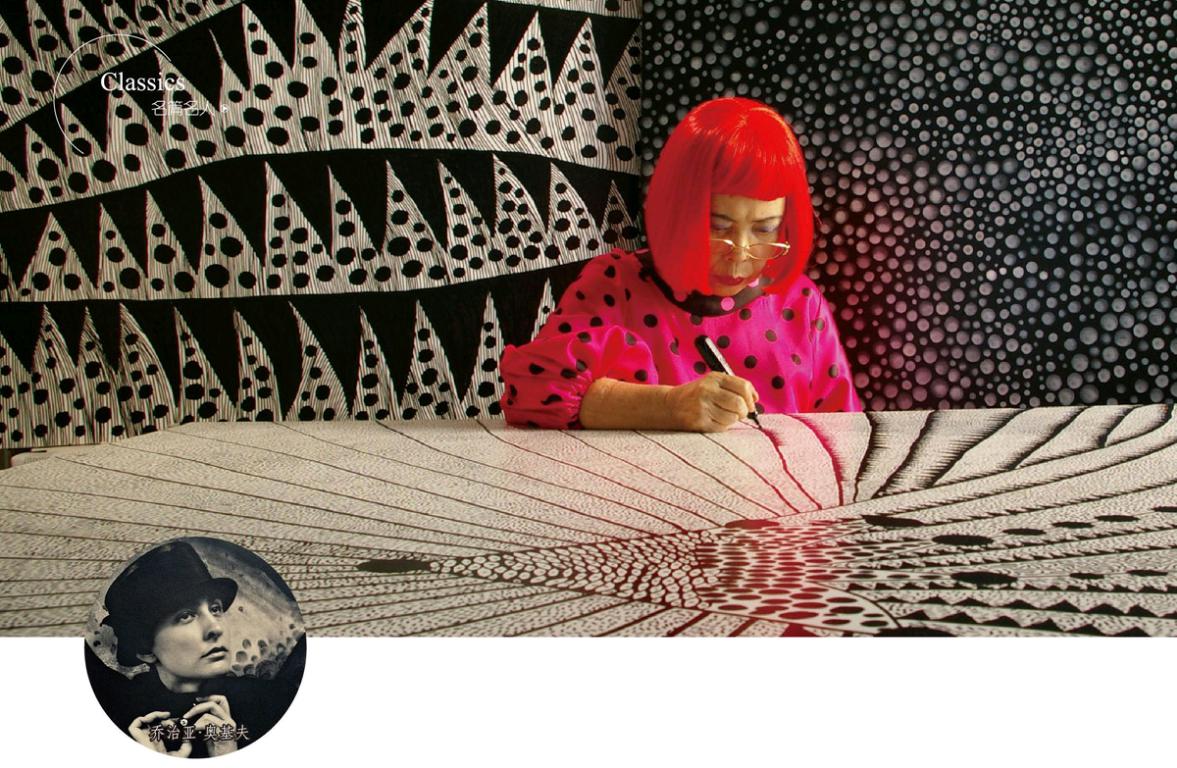

She began to absorb the influences of cubism and surrealism, gleaned from magazines. In these styles she was almost entirely self-taught. Her artwork started to attract attention in Japan, where she staged several exhibitions. Some time earlier she had discovered a book by Georgia OKeeffe12) in a second-hand bookshop in Matsumoto. Something connected and she sent OKeeffe a letter, enclosing several of her watercolours. To her astonishment, OKeeffe wrote back with words of encouragement. It was the first of several letters the great American artist would send the “lowly Japanese girl.”

In spite of OKeeffes warnings that New York would be a tough place for a single Japanese woman, Kusama decided she belonged in the art scene of Americas greatest city. It was difficult to travel in those days. Japanese were restricted in the amount of foreign currency they could take out of the country, and Kusama had to sew bundles of notes into the lining of her clothes. Eventually, she made her way to New York, via Seattle, where she had persuaded one gallery to stage a small exhibition.

Her first years in New York, where she was to spend more than 15 years, were financially and psychologically traumatic. Winters in her unheated apartment were so cold she stayed up all night painting. She called it a “living hell.” But it did not lack for excitement. Kusama, a frenetic experimenter, absorbed everything she could. Though she played on13) her exotic qualities as a Japanese woman, often wearing a kimono14), she became very much an American artist. “America is really the country that raised me, and I owe what I have become to her,” she wrote. Within a year she was ready to strike out on her own, telling a Japanese magazine, “I am planning to create a revolutionary work that will stun the New York art world.”

The revolution came in the form of lace-like paintings that she called “infinity nets.” She filled huge canvases, sometimes more than 30ft-long, with endlessly repeated white loops of paint. Though it must not have looked that way at the time, the “infinity nets” were to become her defining creation.

In 1966, heart problems now compounding her psychiatric afflictions, she went uninvited to the Venice Biennale15). There, dressed in a golden kimono, she filled the lawn outside the Italian pavilion with 1,500 mirrored balls, which she offered for sale for 1,200 lire apiece. The authorities ordered her to stop, deeming it unacceptable to “sell art like hot dogs or ice cream cones.” Andrew Solomon16), writing in Artforum many years later, said Kusamas “lust for fame” had to be put into context. Comparing her to Andy Warhol17) he wrote, “It should not be forgotten that she was less readily accepted since she was a woman, and battling for ground in a foreign tongue, and living in a society recovering from aggressive wartime prejudice against Japan.”

Around this time, she began to stage “naked happenings18).” It was perhaps the height of her fame, but a low point in her reputation. Bands of Kusama followers, whom she recruited through newspaper advertisements, would descend on19) a public place such as the New York Stock Exchange. There they would disrobe and cavort20) around to the sound of bongo drums, while Kusama would daub polka dots on their naked bodies. Most of the happenings were quickly curtailed by the police. One of the events took place in the famous New York financial district. Kusama issued a press release in which she suggested, in capital letters naturally, that her aim was to “OBLITERATE WALL STREET MEN WITH POLKA DOTS.” In this, as in many things, she was ahead of her time.

By 1973, depressed, broke and facing a media backlash after her five minutes of uber-fame, she returned forlorn to Japan. The reception was hostile. She knew no one and belonged to no Japanese art movement. “It must have been deeply humiliating for her to come back to Japan,” says Morris, the Tate curator. “She had a breakdown. She needed surgery. She had no money. It was burnout.”

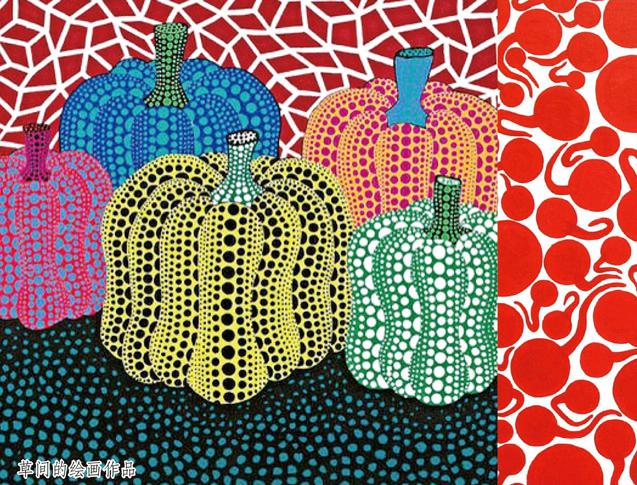

Kusama checked herself into the Seiwa Hospital for the Mentally Ill and eventually took up permanent residence. In the 1970s and 1980s she drifted into semi-obscurity, though she wrote poetry and fiction that won her a cult following in Japan. Only in 1989, when New Yorks Center for International Contemporary Arts staged a retrospective was interest revived in her art. She became more active again, mounting several one-woman shows in the US. In 1993, she went to the Venice Biennale, this time officially, where she produced a mirrored room filled with the pumpkin sculptures that are now central to her repertoire21). Today, her silver pumpkins fetch around half a million dollars each. Kusamas revival gained even greater force in 1998 with a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That was the same location where she had been stopped from staging an unauthorised protest 30 years before. Her career had come full circle.

She does not want to be associated with other commercially successful Japanese artists, such as Yoshitomo Nara22) or Takashi Murakami23). “Such Japanese art is categorised as kawaii culture,” she says. “I have never seen my art as kawaii like that. I dont want to be seen as a Japanese artist. I just want to be able to explore my art freely in an international context.”

These days Kusamas biggest obsession is her legacy. When she was told about the price her silver pumpkins fetched, she nearly cried, not because of the financial gain but because of the recognition such large sums implied. Several times, often unprompted, she mentions the foundation she has established to spread her fame after she is gone. “I am always trying to transmit my own message to as many people as possible,” she says. “My main message is please stop war and live out the brilliance of life. I want to keep my profile as high as possible even after I have died.”

草间弥生87岁了。但是,当她坐在带有蓝色圆点图案的轮椅上被推进房间时,她看起来更像个婴儿,就是那种你可以在英国童话剧里看到的由成年人扮演的婴儿。就日本女性而言,她的脸盘偏大,与她偏于小巧的身材颇不相称。除了那双又大又圆、目光如炬的眼睛和唇上那抹深红色的口红,她的五官透出几分阳刚之气。她头戴艳丽的红色假发,身穿一件圆点图案的连衣裙,脖子上围着一条带有黑色波形曲线花纹的红色长围巾。不处于聚光灯下时,卸下引人注目的红色假发和过于鲜艳的服饰,她看上去就是一个头发花白的和蔼老妇人。这个转变就仿佛她自童年起就着迷地不断复制的图形从画布上溜了下来,进入了活生生的现实世界中。

草间的故事开始于氛围保守的日本农村。1929年,她出生在长野县松本市的一个苗木商人家庭。在一张她十岁左右拍摄的老照片上,她留着短发,表情严肃,手拿一大捧菊花,是个相当漂亮的小姑娘。她的母亲出身门第很高,于是她的父亲,一个经常流连于花街柳巷的浪子,入赘随了她母亲的姓氏——草间。大约在拍摄这张照片时,草间已经开始画铅笔素描了,主要是圆点和网状图案。就连她为母亲画的肖像上也布满了小点,仿佛母亲正在出水痘似的。她讨厌母亲卫道士般严苛的价值观。“我的父母非常讨厌,”她说,“我受不了他们。他们非常保守。我的家族经营那门生意有一百年之久了。我父母的做派和道德观念都非常守旧。”

草间从很小的时候就有过“幻视和幻听”的经历。在她的自传中,她写到自己坐在紫罗兰花丛中的经历。“有一天,我忽然抬起头,发现每一朵紫罗兰都有各自独特的、像人一样的面部表情。令我大吃一惊的是,它们都在对我说话。”还有些时候,“突然之间,我周围的一切都在闪闪发光。好多不同的画面跃入我的眼中,令我目眩神迷、目瞪口呆”。每当出现这类幻觉的时候,她都会急忙跑回家,把自己看到的东西画下来。

1948年,战争结束后,她在京都开始正规学习日本画——一种日本的传统绘画。她憎恨刻板的师徒制,在这种制度下,学生要通过老师吸收传统。“想起在京都的生活,我就想吐。”她说。

她开始汲取搜集自杂志的立体主义和超现实主义作品的影响。她几乎完全靠自学掌握了这些风格。她的画作开始在日本引起关注,举办过几次展览。此前早些时候,她曾经在松本的一家二手书店发现了一本乔治亚·奥基夫的书。由于感到与对方有相通之处,她给奥基夫写了封信,信中附上了她的几幅水彩画。令她大感意外的是,奥基夫给她回了信,写了些鼓励的话语。这是那位伟大的美国画家写给这个“卑微的日本女孩”的几封信中的第一封。

尽管奥基夫警告过她,纽约对于一名单身日本女性而言是个艰难的地方,草间依然认定自己属于美国最伟大城市的艺术舞台。在那个年代,旅行不是件容易的事。当时日本人携带出境的外汇数量受到限制,草间不得不把几捆钞票缝在衣服的衬里中。最终,她去了纽约。其间,她曾取道西雅图,说服当地的一家画廊为她举办了一场小型画展。

她在纽约生活的时间超过了15年。刚到纽约的头几年,无论从经济上还是从心理上都是令人痛苦的。她的公寓没有暖气,冬天屋里寒冷刺骨,她只好彻夜不眠,一直作画。她将那几年的生活称作“人间地狱”。但其中也不乏令人兴奋之处。草间是一个极其热衷于尝试新鲜事物的人,吸收着她所能吸收的一切养料。对于自己作为一名日本女性所具有的异域特色,她会加以利用,时常身穿和服,但她实际上变成了一个非常美国化的艺术家。“美国是真正养育我的国家,我能有今天,要感谢她。”她这样写道。不出一年,她就准备好独自闯出一条新路了,她告诉一家日本杂志:“我正在计划创作一件革命性的作品,一件将震惊纽约艺术界的作品。”

这场革命以网眼状绘画作品的形式出现,她将这些绘画作品称作“无限的网”。她用颜料在巨幅画布(有时超过30英尺长)上画满了无限重复的白色圆圈。“无限的网”日后成了草间最具标志性的作品,虽然当时肯定看不出来有多了不起。

1966年,心脏问题加重了她的精神病症状,她未经邀请就去了威尼斯双年展。在那儿,身穿一袭金色和服的草间用1500个镜面反光球摆满了这个意大利展厅外的草坪,并以每个球1200里拉的价格对外出售。主办方责令她停止这一行为,认为“像出售热狗或冰淇淋甜筒般出售艺术”是不可接受的。许多年后,安德鲁·所罗门在《艺术论坛》杂志上撰文道,草间“对成名的渴望”必须放在当时的时代背景下考虑。在将草间与安迪·沃霍尔作比较时,他写道,“别忘了,她当时不太容易被接受,因为她是一名女性,用一门外语争取立足之地,并且她生活在一个对日本战时的强烈偏见尚未消退的社会。”

大约是在这个时候,她开始筹划“裸体偶发艺术”。此时或许她的名气达到了顶点,但她的声誉却降到了最低点。草间通过报纸广告招募她的一群群追随者,他们会突然造访纽约证券交易所这样的公共场所。在那里,他们会宽衣解带,随着小手鼓的鼓点声狂欢起舞,而草间则在他们赤裸的身体上涂画圆点图案。这样的偶发艺术行为大都很快就被警方叫停。著名的纽约金融区就上演过一次这样的事件。为此草间发表过一篇新闻通稿,文中她表明了自己的目标是“用圆点消灭华尔街的男人”——这几个词当然用的是醒目的大写字母。在这件事上,如同在其他许多事上一样,她走在了时代的前面。

到了1973年,草间灰心失落、不名一文,在一时的名声大噪之后面对着媒体的集体抵制,她落寞地回到了日本。她的归来并不受人欢迎。她举目无亲,也不属于日本的任何艺术潮流。“回到日本一定令她深感屈辱,”泰特美术馆馆长莫里斯说,“她的健康状况十分糟糕,需要做手术。她身无分文,心力交瘁。”

草间自己住进了清和精神病院,并最终长期住了下来。20世纪七八十年代,虽然她创作的诗歌和小说为她在日本赢得了一些铁杆支持者,但她还是渐渐沦入几乎被遗忘的境地。直到1989年,纽约国际当代艺术中心举办了一次回顾展,人们才又对她的艺术产生兴趣。她再度变得更加活跃起来,并在美国举行了几次个展。1993年,她参加了威尼斯双年展,这次是受官方邀请前往。在那里,她布置了一间镶满镜子的房间,房间里到处摆放着南瓜雕塑——这些雕塑如今在她所有作品中占有核心地位。现在,她的一个银南瓜的售价约为50万美元。1998年,随着在纽约现代艺术博物馆举办的一场大型展览,草间东山再起的势头更加强劲。30年前,正是在同一个地点,她策划的一场未经官方许可的抗议活动被制止了。她的艺术生涯转了一圈又回到了原点。

她不希望人们将她同奈良美智和村上隆等其他在商业上获得成功的日本艺术家联系在一起。“这类日本艺术属于可爱文化,”她说,“我从来没有把自己的艺术看成是像他们的那样可爱的艺术。我不希望被视为一名日本艺术家,我只想在国际背景下自由地探索我的艺术。”

这些日子,草间最关心的是她的遗产问题。当被告知她的那些银南瓜的价格时,她几乎叫出声来,这并不是因为经济上的收益,而是因为如此高的价格背后隐含着对她的认可。有好几次,她主动提到了她为了在身后继续传播自己的声名而设立的基金。“我一直努力把自己想传达的信息传达给尽可能多的人,”她说,“我主要想传达的是,请停止战争,活出人生的精彩。我希望就算死后,我依然能尽可能地保持自己的高调形象。”

1. pantomime [?p?nt??ma?m] n. (英国尤在圣诞节演出的)童话剧;哑剧

2. at odds:不相称,不和谐

3. prefecture [?pri??fekt??(r)] n. 县;管区,辖区

4. chrysanthemum [kr??s?nθ?m?m] n. 菊花

5. philanderer [f??land(?)r?] n. 玩弄女性者;风流男子

6. geisha [?ɡe???] n.〈日〉艺妓;歌妓

7. prudish [?pru?d??] adj. 假正经的,假道学的

8. hallucination [h??lu?s??ne??(?)n] n. 幻觉

9. Nihonga:日本画,指日本的民族传统绘画。

10. imbibe [?m?ba?b] vt. 吸收(知识、思想等),接受

11. sensei [sen?se?] n. 〈日〉老师

12. Georgia OKeeffe:乔治亚·奥基夫(1887~1986),20世纪最具传奇色彩的美国艺术家之一,她以给人感官享受的花卉特写绘画而著称。

13. play on:利用(感情)

14. kimono [k??m??n??] n. 和服

15. biennale [?bi?e?nɑ?le?] n.〈意〉(尤指两年一次的)现代艺术(或美术)节

16. Andrew Solomon:安德鲁·所罗门(1963~),美国作家,其作品涉及政治、文化和心理学。

17. Andy Warhol:安迪·沃霍尔(1928~1987),被誉为20世纪艺术界最有名的人物之一,是波普艺术的倡导者和领袖。

18. happenings:指偶发艺术(Happening Art),流行于20世纪60年代的美术流派,以表现偶发性事件或不期而至的机遇为手段,重现人的行为过程,展示人的本能反应。

19. descend on:突然造访,突然到达

20. cavort [k??v??(r)t] vi. 雀跃;嬉戏玩闹;(常指)调情玩乐

21. repertoire [?rep?(r)?twɑ?(r)] n. 全部作品

22. Yoshitomo Nara:奈良美智(1959~),日本著名的现代艺术家,作品包括漫画及动画,其笔下的形象非常可爱。

23. Takashi Murakami:村上隆(1926~),日本极具影响力的现代艺术家,他的作品结合了日本当代流行卡通艺术与传统绘画的特点。