A New Species of the Genus Tylototriton (Amphibia: Urodela: Salamandridae) from Eastern Himalaya

2015-10-31JanakRajKHATIWADABinWANGSubarnaGHIMIREKarthikeyanVASUDEVANShantaPAUDELandJianpingJIANG

Janak Raj KHATIWADA, Bin WANG, Subarna GHIMIRE, Karthikeyan VASUDEVAN, Shanta PAUDELand Jianping JIANG

1Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, China

2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 19A Yuquanlu, Beijing 100049, China

3Tribhuvan University, Central Department of Zoology, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal

4CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Laboratory for the Conservation of Endangered Species,Uppal Road, Hyderabad 500048, India

5Himalayan Research and Conservation Nepal, GPO Box 8975 EPC 5997, Kathmandu, Nepal

A New Species of the Genus Tylototriton (Amphibia: Urodela: Salamandridae) from Eastern Himalaya

Janak Raj KHATIWADA1,2**, Bin WANG1**, Subarna GHIMIRE3, Karthikeyan VASUDEVAN4, Shanta PAUDEL5and Jianping JIANG1*

1Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, China

2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 19A Yuquanlu, Beijing 100049, China

3Tribhuvan University, Central Department of Zoology, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal

4CSIR-Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Laboratory for the Conservation of Endangered Species,Uppal Road, Hyderabad 500048, India

5Himalayan Research and Conservation Nepal, GPO Box 8975 EPC 5997, Kathmandu, Nepal

A new species of the genus Tylototriton is described from eastern Himalaya based on molecular and morphological comparisons. The new species is diagnosable from the closely-related species by having light brown colouration in dorsal region in life, fat and blunt snout, greatly separated dorsolateral bony ridges on head and straightthick tailfn. In addition to head morphology, the new species is also morphologically distinguishable from its closelyrelated species Tylototriton shanorum by having 16 dorsal warts and average smaller Snout Vent Length (SVL).

Tylototriton himalayanus sp. nov., eastern Himalaya, morphology, molecular phylogeny, taxonomy

1. Introduction

The salamandrid genus Tylototriton Anderson, 1871 ranges across eastern Himalaya, Indochina and South China, and presently includes 21 species (Fei et al.,2012; Frost, 2015; Le et al., 2015). The genus is divided into two subgenera, subgenus Tylototriton regarded as T. verrucosus species group and subgenus Yaotriton referred as T. asperrimus species group (Dubois and Raffaëlli, 2009; Fei et al., 2005). Noticeably, 15 species have been newly described in recent six years (Chen et al., 2010; Fei et al., 2012; Hou et al., 2012; Le et al.,2015; Nishikawa et al., 2013a, b; Nishikawa et al., 2014;Phimmachak et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2012; Stuart et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2012), which greatly promote species diversity of Tylototriton. But,some cryptic species are still need to be confirmed(Nishikawa et al., 2013a; Nishikawa et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2013). Some of the newly-described species are found on the edge of the distribution of Tylototriton,for example, T. notialis, T. uyenoi and T. shanorum are from the southern distributional margin of this genus(Nishikawa et al., 2013a; Nishikawa et al., 2014;Stuart et al., 2010). Eastern Himalaya is reported as the westernmost distributional edge of the genus Tylototriton. Tylototriton salamanders here have been named as T. verrucosus but found genetically differentiated from other populations of Tylototriton (Weisrock et al., 2006;Nishikawa et al., 2014). These reports indicated that the Himalayan population of this genus was probably a new species. However, this conclusion was supported by only one sample from Nepal without any morphological description.

This study, therefore, was carried out in the Illam District, eastern Nepal and Darjeeling, northeastern India in 2011-2012. Three populations of Tylototriton from eastern Nepal and one from northeastern Indiawere surveyed. In this study, mitochondrial DNA and morphological characters were used to evaluate the taxonomic status of these Tylototriton populations(Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Molecular analysis We obtained tissue of 39 Tylototriton salamanders from three sites in Illam District,Mechi of Nepal, one sample from Darjeeling, India and one sample of T. verrucosus from the type locality Husa,Longchuan County, Yunnan Province of China (Table 1;Figure 1).

Total genomic DNA was extracted from muscle or liver preserved in 95% ethanol using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Fragments of the complete NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (ND2) gene and part of cytochrome b (cytb) gene were amplifed and sequenced. The primers and PCR conditions for amplifying cytb gene fragment were chosen according to Moritz et al.(1992), and those for amplifying ND2 gene according to Shen et al. (2012). PCR products were sequenced with bi-directional sequencing using primers for PCR. New sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KT765132-KT765212.

For phylogenetic analysis, we downloaded ND2 gene sequences of 33 samples of 19 known Tylototriton species from GenBank (Table 1). We also downloaded ND2 gene sequences of each species of Echinotriton andersoni and Pleurodeles waltl from Genebank as outgroups according to Zhang et al. (2008). GenBank accession numbers of all ND2 sequences used here are presented in Table 1. For further investigation of the genetic split between the Himalayan population and its congeners, we downloaded cytb gene sequences of 146 individuals of 19 T. shanjing populations (Yu et al., 2013), 3 samples of T. shanorum,and 1 for each of T. kweichowensis and T. taliangensis(GenBank accession numbers of them are JX854457-JX854515, JX854517, JX444703, EF627452 and EF627455).

All DNA sequences were aligned using Clustal X 1.83 (Thompson et al., 1997) with default settings and manually adjusted. Pairwise divergences (uncorrected p-distance) between species on ND2 dataset were determined in MEGA 6.0.5 (Tamura et al., 2013). Haplotypes were identifed using DAMBE 5.3.109 (Xia,2013).

Maximum parsimony (MP) and Bayesian inference(BI) analyses were conducted to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships among the taxa based on haplotypes of the ND2 gene sequence dataset. MP analysis, which was implemented in PAUP version 4.0b10 (Swofford, 2003), involved heuristic searches of 1 000 random-addition replicates using tree bisectionreconnection (TBR) branch swapping. Bootstrap supports(bs) for nodes of the resulting MP tree were assessed by analyses of 1 000 bootstrap replicates. For Bayesian analyses, the best-fit substitution model was selected under the Bayesian Information Criterion by the program jModeltest 2.1.4 (Darriba et al., 2012). The best-fit substitution model for the ND2 dataset was GTR + I + G. BI analyses were conducted in the program Mrbayes 3.1.2(Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). Two dependent runs were initiated each with four simultaneous Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains for 30 million generations and sampled every 1 000 generations. The convergence of chains and burn-in period of all runs were examined by plots of log-likelihood scores and low standard deviation of split frequencies, then we discarded the frst 25% generations as burn-in, and then used the remaining trees to create a 50% majority-rule consensus tree and to estimate Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP). To further visualize the degree of genetic splits among the Himalayan population and the closely-related species, we reconstructed phylogenetic network using Splittree 4.11.3(Huson and Bryant, 2006) based on cytb gene sequence dataset, and the supports of lineages were evaluated by 1 000 bootstrap replicates.

2.2 Morphological analyses Following the work by Nishikawa et al. (2014), eastern Himalayan Tylototriton was regarded as the sister lineage to T. shanorum from Myanmar. So we firstly compared the morphological characters of Himalayan specimens with the holotype T. shanorum as described by Nishikawa et al. (2014). Furthermore, Himalayan salamander was previously regarded as T. verrucosus (Frost, 2015). So we also compared the morphology between the Himalayan population and topotypic T. verrucosus from the type locality (Husa, Longchuan County, Yunnan Province of China). Similarly, considering the taxonomic debate and confusion between T. verrucosus and T. shanjing, we also included in our morphological comparison T. shanjing samples from the type locality (Jingdong County, Yunnan Province of China) and Baoshan population from Baoshan City, Yunnan Province of China.

A total of 52 adult males and 39 adult females were included for morphological comparisons. Among them, 13 females and 32 males were from Himalayan population. Out of total 45 samples, only 39 samples were used for molecular analysis. The information for specimens used in morphological comparison is given in Table 3. Specimens were deposited in Natural History Museum, Tribhuvan University, Soyambhu, Kathmandu,Nepal (NHMTU) and Chengdu Institute of Biology,Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China (CIB,CAS; Appendix 1). The following 21 measurements were taken for morphometric analyses: total length (TL,from tip of snout to tip of tail); snout-vent length (SVL,from tip of snout to posterior edge of vent); head length(HL, from jugular fold to snout tip); head width (HW,maximum head width); snout length (SL, from tip of snout to the anterior corner of eye); lower jaw length(LJL, from jaw angle to tip of lower jaw); eyelid-nostril length (ENL, minimum distance between eyelid and nostril; internarial distance (IND, minimum distance between the external nares); upper eyelid width (UEW,greatest width of upper eyelid); upper eyelid length (UEL,greatest length of upper eyelid); axilla-groin distance(AGD distance between axilla and groin); trunk length(TRL, from gular fold of throat to anterior tip of vent);tail length (TAL: from anterior tip of cloaca to tip of tail):vent length (VL: maximum length of cloacal opening);basal tail width (BTAW: tail width measured at the base of tail); medial tail width (MTAW: tail width measured at the medial section of tail); basal tail height (BTAH: tail height measured at the base of tail); medial tail height(MTAH: tail height measured at the medial section of tail); length of arm (LA: distance from axilla to tip of elbow); LH (length of hand: distance from elbow to longest fnger); LT (length of tibia: distance from groin to knee); LF (distance from knee to tip of longest toe). The sex and maturity status were identified by checking the state of cloaca (Anders et al., 1998; Schleich and Kästle,2002; Sparreboom, 2013). Morphological measurements were made using a digital dial caliper to the nearest 0.01 mm and weights of individual species were measured by digital weight machine to the nearest 0.01 gm.

Morphological differences between populations were examined by Student's t-test (for parametric data) and Mann-Whitney U Statistic (for non-parametric data),based on SVL and 20 ratio values to SVL (R, %). Based on 20 log10-transformed values of the metric characters,Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to see the overall morphological variation by BiodiversityR package(Kindt and Coe, 2011) in R 2.13.1 (R Development Core Team, 2009). In the Nepal Himalaya population,female group were significantly larger than male group in total length (Mann-Whitney U Statistic = 60.000, P <0.001) and SVL (Mann-Whitney U Statistic = 125.000,P = 0.039). Therefore, we separately analyzed the male and female groups. Indian specimens collected from Darjeeling District were not included for further morphological comparisons due to lack of information about male and female populations.

3. Results

3.1 Molecular analyses Aligned dataset of ND2 contained 1 035 bps including 447 variable sites and 273 parsimony informative sites, and the dataset of cytb contained 753 bps including 157 variable sitesand 103 parsimony informative sites. Five haplotypes were recognized from 41 samples from the Himalayan populations. The number of variable sites among these haplotypes was only four. MP and BI analyses yielded nearly identical topologies (Figure 2 A). The genus Tylototriton was weakly supported as a monophyly by MP analysis (bs = 70), but not supported by BI analysis (bpp = 0.85). Tylototriton was divided into two major clades,Clade A (bs = 91 and bpp = 1.00) and Clade B (bs = 93 and bpp = 1.00) which were corresponding to subgenus Tylototriton and subgenus Yaotriton, respectively. Five haplotypes recognized from all eastern Himalayan samples were mixed together and formed a monophyletic clade (bs = 100 and bpp = 1.00) which were clustered with the clade including T. shanorum samples (bs = 85 and bpp = 0.95) in Clade A. But our result revealed that the Himalayan population was paraphyletic with the clade containing T. verrucosus, T. shanjing, T. anguliceps, T. uyenoi, T. daweishanensi and T. yangi (bs = 90 and bpp = 0.99). As note, the topotypic T. verrucosus were deeply nested with the T. shanjing populations. The phylogenetic network analyses based on cytb dataset similarly strongly supported the splits between the Himalayan population and its closely-related species (bs = 100; Figure 2 B).

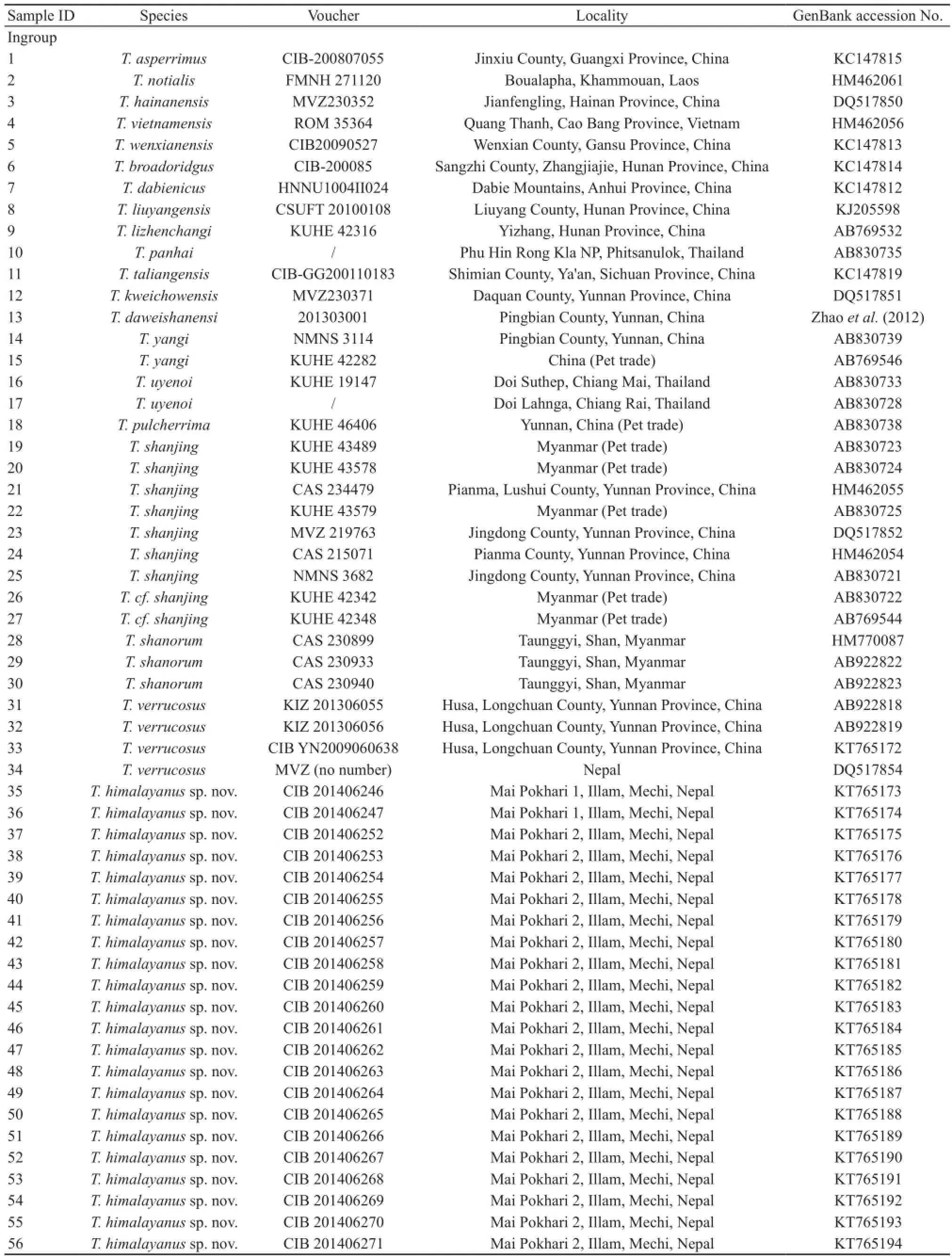

Table 1 Voucher specimens, localities and GenBank accession numbers for samples used in the molecular phylogenetic analyses based on ND2 dataset.

(Continued Table 1)

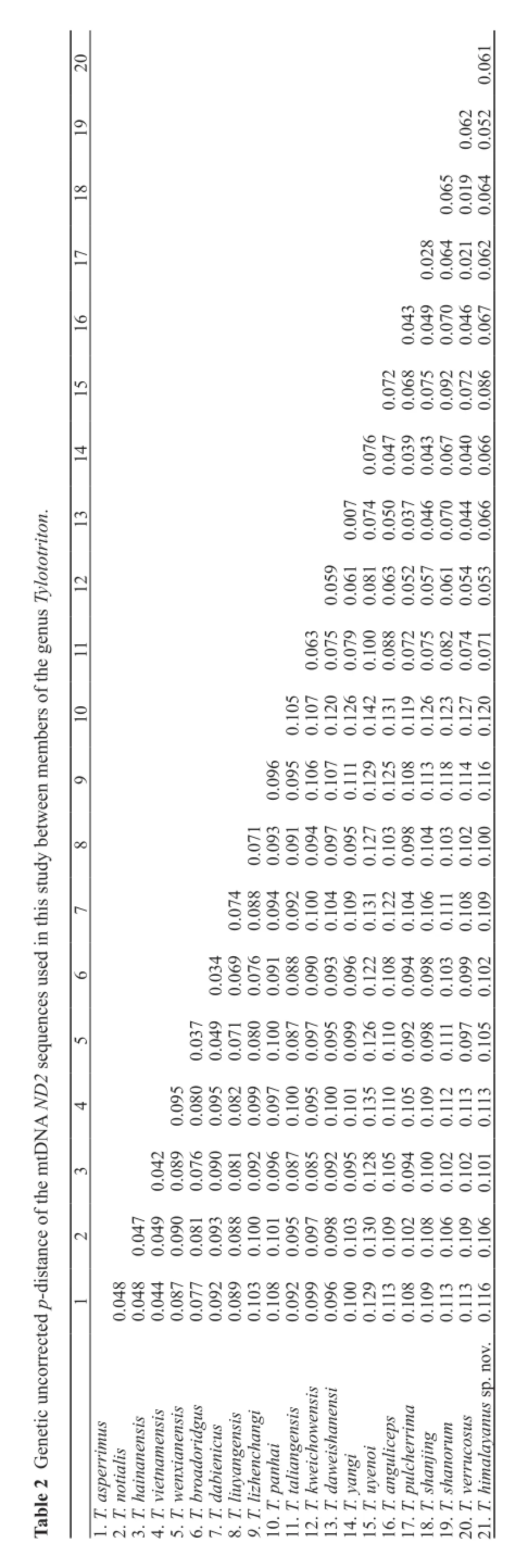

Interspecifc genetic uncorrected p-distance of ND2 in the genus Tylototriton ranged from 0.7%-14.2% (Table 2). The p-distance between the Himalayan population and the other species of Tylototriton ranged from 5.2% to 12%.

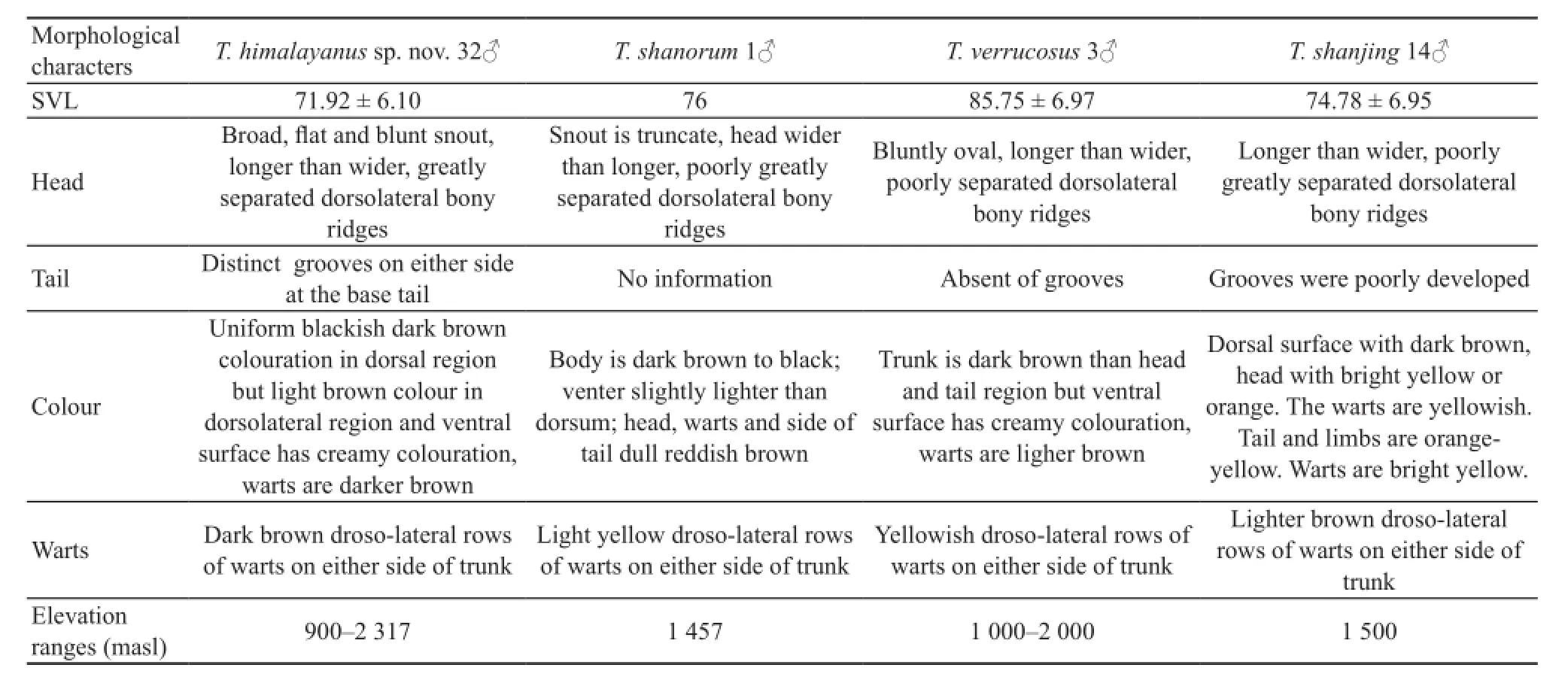

3.2 Morphological comparisons Morphometric comparisons between the Himalayan population and the closely-related species are shown in Table 3,and morphological differences on several diagnostic characters among them are presented in Table 4.

Himalayan population versus T. shanorum Himalayan Tylototriton showed distinct morphological differences from T. shanorum (Table 4). Himalayan population has 16 dorsal warts but T. shanorum has 14 dorsal warts(Nishikawa et al., 2014). Moreover, the average SVL of Himalayan male population (71.92 ± 6.10 mm, range 87.70-63.10) were smaller than holotype T. shanorum(76.0 mm). Furthermore, the head of the Himalayan population had longer length than width but that of T. shanorum has greater width than length. In addition,Himalayan population showed great differences with T. shanorum in coloration from head to tail (Table 4).

Himalayan population versus the topotypic T. verrucosus In male, the SVL of Himalayan population was smaller than topotypic T. verrucosus (Mann-Whitney U-test = 6.00, P = 0.014). Himalayan population was significantly larger on RSL, RIND, RTL and RBTAH ratio % value of SVL but significantly smaller on RENL, RBTAW and RMTAW than T. verrucosus (P <0.05). Himalayan female population was significantly smaller than T. verrucosus only on RBTAW (P < 0.01). Himalayan population could also be separated from the topotypic T. verrucosus on grooves on the tail, state of warts and coloration (Table 4).

Himalayan population versus the topotypic T. shanjing of Jingdong population In male, the SVL of Himalayan population and topotypic T. shanjing were similar (Mann-Whitney U-test = 14, P = 0.097). Himalayan population was significantly larger than T. shanjing of Jingdong population on RTL, RHL, RHW, RSL, RENL, RIND,RTRL, RTAL, RVL, RBTAH, RLA, RLH, RLT and RLF of percentage SVL ratio value (P < 0.05). In female population, Himalayan Tylototriton was significantly larger than T. shanjing on RTL, RHL, RHW, RSL, RENL,RIND, RUED, RTRL, RTAL, RVL, RBTAH, RMTAH,RLA, RLH, and RPPLF (P < 0.05). They were also different in the shape of head, development of grooves on the tail, state of warts and coloration (Table 4).

Himalayan population versus T. shanjing of Baoshan population In male, the SVL of Himalayan population and T. shanjing of Baoshan population were similar(Mann-Whitney U-test = 26.00, P = 0.20). Himalayan population was significantly larger only on RENL (P <0.05) and significantly smaller on RUEL and RBTAW(P < 0.05) than T. shanjing of Baoshan population; but in female, the percentage SVL ratio value showed no signifcant difference in any character between these two populations.

The results of the PCAs exhibited the overall morphological difference among the Himalayan population and its closely-related species. In male,the first two principal components axis explained for 52.8% of the total variation; and in female, the frst two principal components axis explained for 57.5% of the total variation. We constructed PCA plots of the first principal component (PC1) versus the second (PC2) for the male and female groups, respectively (Figure 3). Both PCA graphs of male and female groups showed that the Himalayan population was clearly separated from the closely-related species. In addition, on PCA graph of male(Figure 3 A), the topotypic T. verrucosus was clustered with T. shanjing populations especially with the Baoshan population, but on the PCA graph of female, T. verrucosus was separated from T. shanjing populations (Figure 3 B).

The Himalayan specimens are different from its closely-related species on colorations and the shape of snout, dorsolateral bony ridges on head and tailfn (Figure 4). In life, the dorsal region of the Himalayan individuals is dark to light brown, and in preservation, body colour faded to a lighter blackish brown (Figure 4 A and G). But the dorsal region of the topotypic T. verrucosus specimens are blackish brown with dark to light brown warts(Figure 4 H) both in life and preservation, and T. shanjing have blackish-brown background and yellow warts on dorsal region (Figure 4 I and J). Snout of the Himalayan specimens is more fat, broad and blunt than other species(Figure 4 K, L, M and N; Table 4). The dorsolateral bony ridges on head of the Himalayan specimens were found to be wider separated than those of other populations (Figure 4 K, L, M and N; Nishikawa et al., 2014). The tailfn of the Himalayan specimens is straighter and thicker than others (Figure 4 C, D, E and F). The base of tail has distinct grooves and showed similar character with T. verrucosus but this character is absent in T. shanjing and T. shanorum (Nishikawa et al., 2014).

Based on the distinct morphological and molecular characteristics of the eastern Himalayan specimens from other species of the genus Tylototriton, we described the eastern Himalayan Tylototriton as a new species.

3.3 Description

Tylototriton himalayanus sp. nov.

Holotype NHMTU17A-0098, adult male (Figure 4 A and B), SVL 73.95 mm, was collected by Janak RajKhatiwada, Shanta Paudel and Subarna Ghimire from Mai Pokhari, Illam District, Mechi, eastern Nepal (27°0'25" N 87°55'48" E at an elevation of 2110 m) on 09 July, 2014.

Table 3 The morphometric differences among the Himalayan Tylototriton population, topotypes of T. verrucosus, topotypes of T. shanjing and T. shanjing from Baoshan city of China. All measurements are presented as Mean ± SD and range in parentheses (in mm).

Paratypes NHMTU17A-0098-1, adult male, collected by Janak Raj Khatiwada, Shanta Paudel and Subarna Ghimire from the same place of the holotype on 09 July,2014. A 2-C002, female adult, Mechi Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University was collected by Kalu Ram Khubu Rai from the same place on June 6, 2003.

The holotype and paratypes were deposited in the Natural History Museum, Tribhuvan University,Soyambhu, Kathmandu, Nepal (NHMTU).

Etymology The specific epithet is derived from the current distribution range of the species in the easternHimalaya.

Table 4 Morphological comparison of males between the Himalayan population, T. shanorum, T. verrucosus and T. shanjing. Data for T. shanorum is derived from Nishikawa et al. (2014).

Diagnosis The new species is a member of sub-genus Tylototriton. It is diagnosed from other members by having the following morphological characters: medium size salamander male 87.70-63.10 mm SVL and 97.00-66.00 mm in females, dorsolateral bony ridges on head present; quadrate spine absent, broad and fat head, blunt snout, moderate-sized eyes with granular upper eyelids. The two lines of dorsolateral bony ridges on head are distinct and greatly separated. The body shows pairs of longitudinal lines of knob-like 16 dorsal warts, with fnely granular skin and tail. Tail compressed laterally, with a well-developed fn fold. The new species has light brown colour with darker warts in life.

Colour In life, dark to light brown colouration in dorsal region, light brown colour in dorsolateral region, ventral surface has creamy colouration. Tail, hand and feet are comparatively lighter brown than body colour. The ventral side of digits is rusty cream but palms and soles are dull cream colour. In preservation, the body color faded to a lighter blackish brown, and brown color to lighter brown.

Description of the holotype Adult male shows the following measurements with percentage ratio proportions of SVL 73.95 mm (R: /SVL*100): TL 191%; HL 27%;HW 23%; SL 21%; LJL 5%; ENL 7%; IND 12.7%; UEW 5.3%; UEL 3%; OL 2.7%; AGD 52%; TRL 73% ; TAL 91% ;VL 16%; BTAW 2%; MTAW 13%; BTAH 13%;MTAH 12%; LA 13%; LH 21%; LT 14%; LF 25%. Head is bluntly oval shaped; HL is slightly longer than HW. Snout is blunt, clearly extending beyond the lower lip. The bony ridges are present on either side of the head and are extended behind eyes. Eye is moderate size with round pupils and black irises with large, granular upper eyelid. Skin of body is granular. Tail compressed laterally, with well-developed fin fold, a little shorter than snout-vent length. Uniform dark brown colouration in dorsal region but light brown colour in dorsolateral region, ventral surface has creamy colouration. Tail is comparatively lighter brown than body colour. The ventral side of digits is rusty cream but palms and soles are dull cream colour. The cloaca has a small longitudinal slit. Fingers and toes not webbed. Front and hindlegs muscular, with four fingers on the front legs and five toes on the hindlegs;relative lengths of fingers 3>2>4>1; relative lengths of toes 3>4>2>5>1.

Variation A detailed analysis of the morphology and life history of Tylototriton salamanders from eastern Nepal can also be found in Anders et al. (1998). Our study revealed greater sexual dimorphism in salamanders from the eastern Himalaya. Females tend to be larger than males in different morphological traits. Summary statistics is provided in Table 3. The SVL in males ranged from 87.70-63.10 mm (71.92 ± 6.1 mm) and 97.00-66.00 mm (76.06 ± 7.53 mm) in females. Similarly, TL of males was 141.33 ± 6.35 mm and 152.55 ± 11.70 mm in females and body weight of males were 14.50 ± 1.39 gm in males and 17.69 ± 5.66 gm in females, respectively(Table 3). The body temperature was 19.39 ± 0.92 °C in male and 19.88 ± 0.54 °C in female. There was no distinct colour variation between male and female. The ground colouration varied from dark brown to light brown. Head is blunt and oval, internarial distance smaller than eye tonostril length, tail length is almost equal to SVL, medial tail height is similar to basal tail height in males but larger in females, forelimb is shorter than hindlimb, vent length is longer in male compared to female.

The dorsal body surface has two series of rounded knoblike 16 black warts that originated nearby the forelimb and extended backward at the end of vent. The clutch sizes vary from 26 to 60 and egg size varies 6 to 10 mm in diameter (Nag and Vasudevan, 2014; Schleich and Kästle, 2002).The fully grown larva has four limbs and three pairs of large gills and longer or little shorter tail than SVL. They have olive-brownish colour thickly speckled with darker markings (Schleich and Kästle,2002; Sparreboom, 2013).

Distribution and natural history Most specimens were collected from permanent and temporary ponds in the Illam District of Nepal (Figure 5). The habitats are characterized as the subtropical hill forest and area is dominated by scattered vegetation, for example, Schima wallichii, Castonopsis indica, Casttonopsis tribuloides,Albizzi sp., Sauraria nepalensis, Rubus ellipticus and Eupatorium adenophorum. Anders et al. (1998) reported the distribution of the new species in five places in the Illam District of Nepal with elevation ranging from 1 100 m to 2 120 m. They also checked the previous record by Shrestha (1988) in Dhankuta District but did not find the species. The distribution of new species is currently known only from the Illam District of Nepal and in Darjeeling District of India (details provided in Nag and Vasudevan 2014). The salamanders are more terrestrial in non-breeding seasons (from October to February) and found hiding under the logs, bushes and stones and come to the breeding ponds in early March or April soon after heavy monsoonal showers (also see Schleich and Kästle, 2002) .

4. Discussions

Salamanders are poor dispersers and highly associated with specific habitat requirements for breeding and larval development (Zamudio and Wieczorek, 2007). Long isolation and local climatic adaptation might cause great differentiation in the morphological and genetic characteristics of species resulting in the formation of new species (Eckert et al., 2008). Based on molecular and morphological characters of individuals from eastern Himalaya, we described them as a new species. Our result revealed that this new species, both morphologically and genetically, is greatly distinct from the closely-related species T. shanorum, T. verrucosus and T. shanjing(Tables 3, 4; Figure 2). Furthermore, molecular analyses showed that the Nepalese and Indian Tylototriton are genetically identical (Figure 2). The sampling locations from Nepal and current study sites in the Darjeeling District, India are in close proximity roughly around 40 km.

The new species is a single representative of the order Caudata and has a restricted distribution in easternHimalaya (Shrestha, 1989; 1984). Eastern Himalaya is also regarded as a biodiversity hotspot due to high biological diversity and endemism (Olson et al., 2001). Recent study by Nag and Vasudevan (2014) also reported a new species from 37 locations in Darjeeling Districts,India. This species inhabits in the mountain and hilly regions, at elevation range of 900-2 317 m above sea level and found living around aquatic habitats, permanent and temporary pools, puddles, lakes and also in the paddy fields (Nag and Vasudevan, 2014; Schleich and Kästle,2002). This species has wider elevation-distribution range than other Tylototriton species (Fei et al., 2009). Tylototriton species has also been reported from Bhutan(Palden, 2003; Wangyal and Gurung, 2012) and other parts of eastern Himalaya (Mansukhani et al., 1976). Therefore, detailed molecular and morphological survey is essential to identify the current range of distribution of this species in eastern Himalaya.

Although the eastern Himalayan Tylototriton has been listed as least concern (LC) by IUCN (Dijk et al., 2009),many authors have reported a rapid decline of Tylototriton populations in South and East Asia (Dasgupta, 1990;Seglie et al., 2010; Seglie et al., 2003). Due to the recent global environment changes and anthropogenic disturbances, the rapid disappearance of the Himalayan wetlands which is the major habitat of Tylototriton has possibly led to the sharp decline of population size of this group (Xie et al., 2007).

Acknowledgements We thank Suman Acharya, Anish Timilsina and Kamal Mukhiya for their assistance during survey work. We are thankful to Kalu Ram Rai,Mechi Multiple Campus and Karan Bahadur Shah,Natural History Museum, Tribuvan University for allowing us to check the specimens and to Indraneil Das,Institute of Biodiversity and Environmental Conservation,University Malaysia Sarawak for providing some literature. We are also grateful to anonymous reviewers for critical comments that greatly improved the quality of our paper. We are grateful to Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC) for provide necessary research permit for amphibian study in the eastern Himalaya. We are also thankful to Wildlife Institute of India and the West Bengal State Forest for supporting the surveys in Darjeeling. This work was supported by the world academy of sciences (TWAS),CAS-TWAS president fellowship program, and the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (NSFC-31201702 granted to Bin Wang and NSFC-31471964 granted to Jianping Jiang).

Anders C., Schleich H., Shah K. 1998. Contributions to the Biology of Tylototriton verrucosus Anderson 1871 from East Nepal (Amphibia: Caudata, Salamandridae). In: H Schleich and W Kastle (eds.) Contributions to the Herpetology of South Asia(Nepal, India) No. 4. Fuhlrott Museum, Wuppertal, Germany,1-26

Chen X. H., Wang X. W., Tao J. 2010. A new subspecies of genus Tylototriton from China (Caudata, Salamandridae). Acta Zootaxon Sinica, 35: 666-670 (In Chinese)

Darriba D., Taboada G. L., Doallo R., Posada D. 2012. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods, 9(8): 772-772

Dasgupta R. 1990. Distribution and conservation problems of the Himalayan newt (Tylototriton verrucosus) in the Darjeeling Himalayas. Hamadryad, 15: 13-15

Dijk P. P., Wogan G., Lau M. W. N., Dutta S., Shrestha T. K.,Roy D., Truong N. Q. 2009. Tylototriton verrucosus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. Retrieved from www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed 21 December 2014

Dubois A., Raffaëlli J. 2009. A new ergotaxonomy of the family Salamandridae Goldfuss, 1820 (Amphibia, Urodela). Alytes,26(1-4): 1-85

Eckert C., Samis K., Lougheed S. 2008. Genetic variation across species' geographical ranges: the central-marginal hypothesis and beyond. Mol Ecol, 17(5): 1170-1188

Fei L., Ye C. Y., Jiang J. P. 2012. Colored Atlas of Chinese Amphibians and Their Distributions. Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, Chengdu. 78-94 (In Chinese)

Fei L., Ye C. Y., Huan Y. Z., Jiang J. P., Xie F. 2005. An illustrated key to Chinese amphibians. Sichuan Publishing House of Science and Technology, Chengdu. 340 (In Chinese)

Frost D. 2015. Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History,New York, USA. Available at: http://research.amnh.org/ herpetology/amphibia/index.html. (Assesses on Sep 23, 2015)

Hou M., Li P. P., Lü S. Q. 2012. Morphological research development of genus Tylototriton and primary confrmation of the status of four cryptic populations. J Huangshan Univ, 14: 61-65 (In Chinese)

Huson D. H., Bryant D. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol, 23: 254-267

Kindt R., Coe R. 2011. BiodiversityR: GUI for biodiversity and community ecology analysis. Version 1.6.

Le D. T., Nguyen T. T., Nishikawa K., Nguyen S. L. H., Pham A. V., Matsui M., Bernardes M., Nguyen T. Q. 2015. A New Species of Tylototriton Anderson, 1871 (Amphibia:Salamandridae) from Northern Indochina Curr Herpetol, 34(1):38-50

Mansukhani M., Julaka J., Sankar H. 1976. On the occurrences of the Himalayan newt Tylototriton verrucosus Anderson from Arunanchal Pradesh, India. Newsletter Zoological Survey, India,2: 243-245

Moritz C., Schneider C. J., Wake D. B. 1992. Evolutionary Relationships Within the Ensatina eschscholtzii Complex Confrm the Ring Species Interpretation. Syst Biol, 41(3): 273-291

Nag S., Vasudevan K. 2014. Observations on overwintering larvae of Tylototriton verrucosus (Caudata: Salamandridae) in Darjeeling, Himalaya, India. Salamandra, 50(4): 245-248

Nishikawa K., Khonsue W., Pomchote P., Matsui M. 2013a. Two new species of Tylototriton from Thailand (Amphibia: Urodela:Salamandridae). Zootaxa, 3737(3): 261-279

Nishikawa K., Matsui M., Nguyen T. T. 2013b. A new species of Tylototriton from northern Vietnam (Amphibia: Urodela:Salamandridae). Curr Herpetol, 32: 34-49

Nishikawa K., Matsui M., Rao D.Q. 2014. A new species of Tylototriton (Amphibia: Urodela: Salamandridae) from central Myanmar. Nat Hist Bull Siam Soc, 60(1): 9-22

Olson D. M., Dinerstein E., Wikramanayake E. D., Burgess N. D., Powell G. V., Underwood E. C., D'amico J. A., Itoua I., Strand H. E., Morrison J. C., Loucks C. J., Allnutt T. F., Ricketts T. H., Kura Y., Lamoreux J. F., Wettengel W. W., Hedao P., Kassem K. R. 2001. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on earth; a new global map of terrestrial ecoregions provides an innovative tool for conserving biodiversity. BioScience, 51(11): 933-938

Palden J. 2003. New records of Tylototriton verrucosus Anderson,1871 from Bhutan. Hamadryad, 27: 286-287

Phimmachak S., Aowphol A., Stuart B. L. 2015. Morphological and molecular variation in Tylototriton (Caudata: Salamandridae)in Laos, with description of a new species. Zootaxa, 4006(2):285-310

Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics,19(12): 1572-1574

Schleich H. H., Kästle W. 2002. Amphibians and reptiles of Nepal. Biology, Systematics, Field Guide. Germany: A.R.G Gantner Verlag K.G.

Seglie D., Roy D., Giacoma C. 2010. Sexual dimorphism and age structure in a population of Tylototriton verrucosus (Amphibia:Salamandridae) from the Himalayan Region. Copeia, 2010(4):600-608

Seglie D., Roy D., Giacoma C., Mushahidunnabi M. 2003. Distribution and conservation of the Himalayan Newt(Tylototriton verrucosus, Urodela, Salamandridae) in the Darjeeling District, West Bengal (India). Russian J Herpetol,10(2): 159-164

Shen Y. H., Jiang J. P., Mo X. Y. 2012. A new species of the genus Tylototriton (Amphibia, Salamandridae) from Hunan, China. Asian Herpetol Res, 1(3): 21-30

Shrestha T. K. 1989. Ecological aspects of the life-history of the Himalayan newt, Tylototriton verrucosus (Anderson) with reference to conservation and management. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc., 86(3): 333-338

Sparreboom M. 2013. Salamanders of the old world. Zeist, the Netherland: KNNV Publishing

Stuart B. L., Phimmachak S., Sivongxay N., Robichaud W. G. 2010. A new species in the Tylototriton asperrimus group(Caudata: Salamandridae) from central Laos. Zootaxa, 2650:19-32

Swofford D. 2003. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony,version 4.0 b10.

Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol, 30(12): 2725-2729

Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F.,Higgins D. G. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface:flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res, 25(24): 4876-4882

Wangyal J., Gurung D. 2012. The distribution of Himalayan Newts, Tylototriton verrucosus in the Punakha-Wangdue Valley,Bhutan. J Threat Taxa, 4(13): 3218-3222

Weisrock D. W., Papenfuss T. J., Macey J. R., Litvinchuk S. N.,Polymeni R., Ugurtas I. H., Zhao E. M., Jowkar H., Larson A. 2006. A molecular assessment of phylogenetic relationships and lineage accumulation rates within the family Salamandridae(Amphibia, Caudata). Mol Phyl Evol, 41(2): 368-383

Xia X. 2013. DAMBE5: a comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol Biol Evol,30(7): 1720-1728

Xie F., Lau M. W. N., Stuart S. N., Chanson J. S., Cox N. A.,Fischman D. L. 2007. Conservation needs of amphibians in China: A review. Sci China C Life Sci, 50(2): 265-276

Yang D. D., Jiang J. P., Shen Y. H., Fei D. 2014. A new species of the genus Tylototriton (Urodela: Salamandridae) from northeastern Hunan Province, China. Asian Herpetol Res, 5(1):1-11

Yu G. H., Zhang M. W., Rao D. Q., Yang J. X. 2013. Effect of pleistocene climatic oscillations on the phylogeography and demography of red knobby newt (Tylototriton shanjing) from Southwestern China. PloS ONE, 8(2): e56066

Zamudio K. R., Wieczorek A. M. 2007. Fine-scale spatial genetic structure and dispersal among spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) breeding populations. Mol Ecol, 16(2): 257-274

Zhang M. W., Yu G. H., Rao D. Q., Huang Y., Yang J. X., Li Y. 2013. A species boundary within the Tylototriton verrucosus group (Urodela: Salamandroidae) based on mitochondrial DNA sequence evidence. J Anim Vet Adv, 12(3): 337-343

Zhang P., Papenfuss T. J., Wake M. H., Qu L. H., Wake D. B. 2008. Phylogeny and biogeography of the family Salamandridae(Amphibia: Caudata) inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Mol Phyl Evol, 49(2): 586-597

Zhao T.Y., Rao D. Q., Liu N., Li B., Yuan S. Q. 2012. Molecular phylogeny analysis of Tylototriton verrucosus group and description of new Species. China Forest Sci, 41: 85-89 (In Chinese)

Prof. Jianping JIANG, from Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China, with his research focusing on taxonomy, systematics and evolution of amphibians and reptiles.

E-mail: jiangjp@cib.ac.cn

**These authors contributed equally to this work.

25 December 2014 Accepted: 27 July 2015

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- Catalogue of the Type Specimens of Amphibians and Reptiles in the Herpetological Museum of the Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences: IV. Lizards (Reptilia, Sauria)

- Rediscovery of Microgecko helenae fasciatus (Schmidtler and Schmidtler, 1972) from Kermanshah Province, Western Iran with Notes on Taxonomy, Morphology, and Habitat

- Genetic Structure and Relationships among Populations of the Caspian Bent-toed Gecko, Tenuidactylus caspius (Eichwald, 1831)(Sauria: Gekkonidae) in Northern Iran

- Structure and Function of the Gastrointestinal Tract of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) Hatchling

- Male Music Frogs Compete Vocally on the Basis of Temporal Sequence Rather Than Spatial Cues of Rival Calls

- Significant Male Biased Sexual Size Dimorphism in Leptobrachium leishanensis