Male Music Frogs Compete Vocally on the Basis of Temporal Sequence Rather Than Spatial Cues of Rival Calls

2015-10-31FanJIANGGuangzhanFANGFeiXUEJianguoCUIStevenBRAUTHandYezhongTANG

Fan JIANG, Guangzhan FANG*, Fei XUE, Jianguo CUI, Steven E. BRAUTHand Yezhong TANG*

1Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. No. 9 Section 4, Renmin Nan Road, Chengdu 610041,Sichuan, China

2Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park MD 20742, USA

Male Music Frogs Compete Vocally on the Basis of Temporal Sequence Rather Than Spatial Cues of Rival Calls

Fan JIANG1, Guangzhan FANG1*, Fei XUE1, Jianguo CUI1, Steven E. BRAUTH2and Yezhong TANG1*

1Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. No. 9 Section 4, Renmin Nan Road, Chengdu 610041,Sichuan, China

2Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park MD 20742, USA

Male-male vocal competition in anuran species may be infl uenced by cues related to the temporal sequence of male calls as well by internal temporal, spectral and spatial ones. Nevertheless, the conditions under which each type of cue is important remain unclear. Since the salience of different cues could be refl ected by dynamic properties of male-male competition under certain experimental manipulation, we investigated the effects of repeating playbacks of conspecific calls on male call production in the Emei music frog (Babina daunchina). In Babina, most males produce calls from nest burrows which modify the spectral features of the cues. Females prefer calls produced from inside burrows which are defined as highly sexually attractive (HSA) while those produced outside burrows as low sexual attractiveness (LSA). In this study HSA and LSA calls were broadcasted either antiphonally or stereophonically through spatially separated speakers in which the temporal sequence and/or spatial position of the playbacks was either predictable or random. Results showed that most males consistently avoided producing advertisement calls overlapping the playback stimuli and generally produced calls competitively in advance of the playbacks. Furthermore males preferentially competed with the HSA calls when the sequence was predictable but competed equally with HSA and LSA calls if the sequence was random regardless of the availability of spatial cues, implying that males relied more on available sequence cues than spatial ones to remain competitive.

male-male competition; advertisement call; sequence cue; spatial cue; call timing.

1. Introduction

In those species in which males compete using vocal communication, animals may change their strategy based on the nature of the spectral cues of the conspecific calls as well the temporal patterns and spatial locations of conspecific vocalizations (Rose and Gooler, 2006). For instance, signalers precisely adjust the timing of call production according to those of other individuals nearby (Reichert, 2012) in order to avoid overlapping vocalizations which may obscure the fine acoustic features of the male's calls (Schwartz, 1987). Males areable to produce calls in advance of rivals because they possess the ability of interval timing, i.e. the ability to time shorter intervals, typically in the range of seconds to minutes (Fang et al., 2014). This may be adaptive for males because in some species females favor the leading calls due to the precedence effect, an inherent property of the auditory system which favors selective perception of the characteristics of the lead stimulus in a pair for determining the spatial locations of fused acoustic signals(localization dominance) (Litovsky et al., 1999; Marshall and Gerhardt, 2010; Zurek, 1987). Accordingly, males successful in mating may produce a greater proportion of leading and non-overlapping calls in chorus compared to unsuccessful males (Fang et al., 2014; Schwartz et al.,2001).

Nevertheless, the background noise in leks or choruses,generated by the chorus attendees, presents a signifi cant challenge for the detection, localization and recognitionof signals by both males and females during the breeding season (Feng and Schul, 2006; Schwartz, 1993; Wells and Schwartz, 2006). One mechanism for amelioration of this problem is spatial separation of calling individuals and directional hearing (Wilczynski and Endepols,2006). Acoustically, animals can identify the species and individual based on temporal and spectral information encoded in the calls. Target localization is dependent largely on the interaural differences in the phase and/or intensity of the frequency components of acoustic signals(Gerhardt and Bee, 2006; Popper and Fay, 2005). Many studies have investigated the relationships between call temporal patterns and species identifi cation and between call spectral characteristics and individual recognition in crickets (Meckenhäuser et al., 2013; Vedenina and Pollack, 2012), songbirds (Gentner, 2007; Hurly et al.,1990; Lohr et al., 1994) and anurans (Gerhardt, 1988;Gerhardt and Bee, 2006). In contrast, only a few studies have attempted to determine how the spatial location of the vocalizing male infl uences vocal competition among other males in the environment (Bee and Gerhardt, 2001a;Feng et al., 2009; Gerhardt and Bee, 2006; Gerhardt et al.,2000).

Although the interaural distances are small, anurans show remarkable sound localizing capability in undisturbed sound fields (Feng and Schellart, 1999;Gerhardt and Huber, 2002). In the present study, the music frog (Babina daunchina) was used as a model for studying the acoustic cues involved in the male-male competition. Babina males produce advertisement calls from either within nest burrows the male has constructed,which typically acoustically alter the calls by their resonant properties, or from outside burrows (Cui et al.,2012). Calls produced from within burrows are highly sexually attractive (HSA) to females as compared to those of low sexual attractiveness (LSA) produced outside burrows because females preferentially approach sources of the former relative to the latter (Cui et al., 2012). Moreover, males stay in their burrows and call in most cases unless there is a very serious disturbance, and that they more strongly responded vocally to playback of HSA calls than LSA calls (Fang et al., 2014). In response to the antiphonal playbacks of conspecific call stimuli with white noise (WN), most males call responsively before the onset of conspecific calls and after the end of WN although call numbers are similar (Fang et al.,2014). Moreover, males compete preferentially with HSA calls when the inter-stimulus interval (ISI) is short(< 4 s) while responding equally to HSA and LSA calls if the ISI is long (≥ 4 s), implying they have evolved the ability of interval timing and could allocate competitive efforts according to the sexual attractiveness of rivals and competitive pressures refl ected by group sizes. Notably,approximately two thirds of male calls occur in response to HSA calls while one third occurs in response to LSA calls when the ISI is short, a preference rate comparable to that previously found for females in phonotaxis experiments (Cui et al., 2012). These findings imply that male call timing in this species is determined by multiple cues reflecting the biological significance of acoustic stimuli, sexual attractiveness of rivals and levels of competitive pressure (Fang et al., 2014). Nevertheless the relative importance of each type of cue for male vocal competition is unclear. In the present study we investigated this matter using controlled experimental conditions.

Both sequence cues (refl ecting the timing and sequence of conspecific calls) and spatial cues (involved in signaling sites) have predictive value for males adjusting their competitive strategy. Sequence cues enable males to predict when the next call will be produced while spatial cues allow the male to predict where upcoming calls will be produced. Although such information would be limited insofar as spatial cues generally play a minor role in grouping or segregating auditory signals (Carlyon and Gockel, 2007; Darwin, 2007), spatial cues might also play a role in individual recognition. For example,gray treefrogs appear more sensitive to spatial cues for simultaneous integration of spectral components of calls from spatially separated sources as compared to sequential integration of temporal elements of calls (Bee,2015; Farris et al., 2005; Farris et al., 2002).

In view of the above considerations we hypothesized that (1) by adjusting their call timing males would compete with rivals more effectively when the sequence cue was available, (2) males could allocate competitive efforts depending on the perceived sexual attractiveness of rivals when the sequence cue was available, and(3) since approximately two thirds of male calls occur in response to HSA calls during antiphonal playbacks with HSA and LSA calls, the percentage of total male advertisement calls produced in response to the HSA call stimuli (defined here as the index of competitive effectiveness) would refl ect the “two thirds” competitive pattern when the sequence rather than spatial cue was available. To test our hypotheses, we broadcasted HSA and LSA calls with predicative or non-predicative spatial and sequence cues and assessed the response patterns of male vocalizations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Site and Subjects The study site (29.35°N,103.17°E, elevation of 1315 m above sea level) is located in the Emei mountain area, Sichuan, China. Experiments were conducted in July and August 2012. Nine ponds of various sizes (6.8 ± 4.1 m2) were selected as adequate numbers of frogs (2-4 males) lived in each pond. The shortest distance between any two ponds involved in this study was more than 100 m so that males in one pond could not have previously competed with the playback calls recorded from another pond. Thus, each subject did not experience the playback stimuli before the experiments. Twenty-five males were used for the playback tests with no male used twice. The local relative humidity and air temperature were 86%-90% and 22.5-23.6 °C, respectively, during the experimental period.

2.2 Stimulus presentation To prevent pseudoreplication,we used two experimental stimuli, which were recorded from the same male, when calling from either inside (HSA call) or outside (LSA call) a burrow (Figure 1). Both calls had five notes and showed temporal and spectral properties close to the average values of the population. Monophonic (broadcasted from the left or right channel)and stereophonic (broadcasted from both the left and right channels simultaneously) call types were constructed and all stimuli were equalized for intensity (65 dB SPL, re 20 μPa; Aihua, AWA6291; Hangzhou, China; measured at 1 m from the speaker for the monophonic stimuli, and from the vertex of the equilateral triangle with 1 m length formed by the three points at which the measurement point and the speakers located and orientated to the measurement point for the stereophonic stimuli).

2.3 Experimental protocol The experiment was conducted under ambient light conditions between 20:30 and 23:30 in order to avoid the effects of visual stimulation and high intensity insect noise which occur from 4:30 to 20:20. For each pond, all frogs but one were removed. The captured individuals were housed in an opaque plastic tank (45×35 cm and 30 cm deep)containing weeds, mud and water, which was located at a substantial distance from the pond, and fed ad libitum with insects. When all experimental protocols were completed, the experimental subject was replaced with another male chosen randomly from the plastic tank for use the next night. The replaced animals were housed in another opaque plastic tank with the same resident conditions. They were returned to the pond after all individuals from each pond were tested once in random order.

Two speakers (SME-AFS, Saul Mineroff Electronics,Elmont, NY, USA) were placed 1 m apart along the pond bank, oriented toward the subject who stayed in his burrow which was located at one of the vertices of the isosceles triangle formed by the three points at which the speakers and subject were located (Figure 2). The playbacks were started about 10 min after the male resumed normal calling behavior following speaker placement.

HSA and LSA call playbacks were presented from either one speaker or stereophonically from both speakers from which either the sequence of call playbacks, the spatial location of each stimulus type or both cues could be made available. Random presentation of eithersequence or spatial position was used to control for the presence or absence of both kinds of cues (see Table 1).

Table 1 Experimental design conditions based on playback patterns.

The experimental playbacks for each subject consisted of four 10 min blocks with 10 min inter-block intervals during which one of four randomly selected playback protocols was employed (Figure S1, supplementary material): 1) The C00 condition with random playback of simultaneous stereophonic stimuli, in which neither sequence nor spatial cues were available (Yost, 2007) (the two digits refer to sequence and spatial cues with 0 and 1 expressing “unavailable” and “available” respectively); 2)The C01 condition with random playback of monophonic stimuli, in which spatial cues were available while no sequence cues were available; 3) The C10 condition with antiphonal playback (alternating HSA and LSA calls)of stereophonic stimuli, in which sequence cues were available while spatial cues were unavailable; and 4) The C11 condition, with antiphonal playback of monophonic stimuli, in which both sequence and spatial cues were available (Table 1). For all experimental conditions, the ISI was set at 1.5 s because previous work has shown that with this interval males not only respond maximally to the playback stimuli but also respond in a characteristic“two thirds” competitive pattern preferring the HSA over the LSA call two thirds of the time (Fang et al., 2014). In each block, LSA and HSA calls were randomly or antiphonally presented for 10 minutes temporally. We randomly varied the speaker assignments and presentation orders among blocks in order to control for possible side biases. All data were used in the analyses for each condition insofar as the males required very few stimuli(no more than 20 stimuli) to recognize the cue patterns and begin consistent calling patterns.

Both subject's vocal responses and playback stimuli were recorded simultaneously using a Sennheiser ME66 microphone (Sennheiser, Wedemark, Germany) connected to a Lenovo Thinkpad X201 laptop at a sampling rate of 44.1 KHz and 16 bit resolution (Figure 2). The microphone was mounted on a long bamboo rod and was held about 0.5 m above the water, orientated towards the subject. Data were excluded for further analysis if the subject suddenly decreased or stopped calling because of a disturbance such as animal barks nearby during the experiment. Data acquired from 17 males were analyzed in the study. All playback orders were randomized using custom-made software in C++ and saved in txt files so that the calls recorded from each subject could be correlated with each playback stimulus.

2.4 Data processing Methods for data analysis were similar to those described previously (Fang et al., 2014). In brief, the number of advertisement calls and their onset time relative to the beginning of the upcoming or ongoing stimulus were measured manually using Adobe Audition 3.0. Since total numbers of advertisement calls produced before, during and after playbacks reflect competitive motivation (Fang et al., 2014), ISIs were divided into two equal phases: a pre-phase defined as the period before the playback and a post-phase defi ned as the period after the playback (see the electronic supplementary material,Figure S2). Thus a completed “trial” consisted of two playbacks and four phases. The fi rst phase occurred before the first playback, the second phase occurred after thefi rst playback, the third phase occurred before the second playback and the fourth phase occurred after the second playback (see Figure S3A). Based on whether the subjects produced calls during playbacks, responsive vocalizations were categorized into two classes: overlapping calls in which call onset occurred during the period that playbacks were occurring and non-overlapping calls that were initiated during the ISI (see Figure S3B).

Subject responsive calls were scored on the basis of the time periods during which the call onsets occurred for each block and each subject, and then averaged for each block and each phase. Thus average numbers of calls produced during the pre-HSA, pre-LSA, post-HSA and post-LSA phases which did not include overlapping calls were calculated (Fang et al., 2014) (see Figure S3A). In addition to these four average values, we also calculated the average numbers of calls produced across the pre- and post- phases including both overlapping and non-overlapping calls (Response to S1/S2 in Figure S3C). The latter average values were used to calculate the proportions of the total responsive calls produced in response to a given playback regardless of whether the response calls overlapped the stimulus calls or not. In addition, the average numbers of notes composing the corresponding responsive calls and the delay between the onsets of the stimulus and overlapping calls were computed. Finally, the percentage of total male advertisement calls which were produced in response to the HSA call stimuli was defined as the index of competitive effectiveness based on the fact that “two thirds” pattern appear in both male and female music frogs, i.e. responding preferably to HSA calls compared to LSA calls (Cui et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2014).

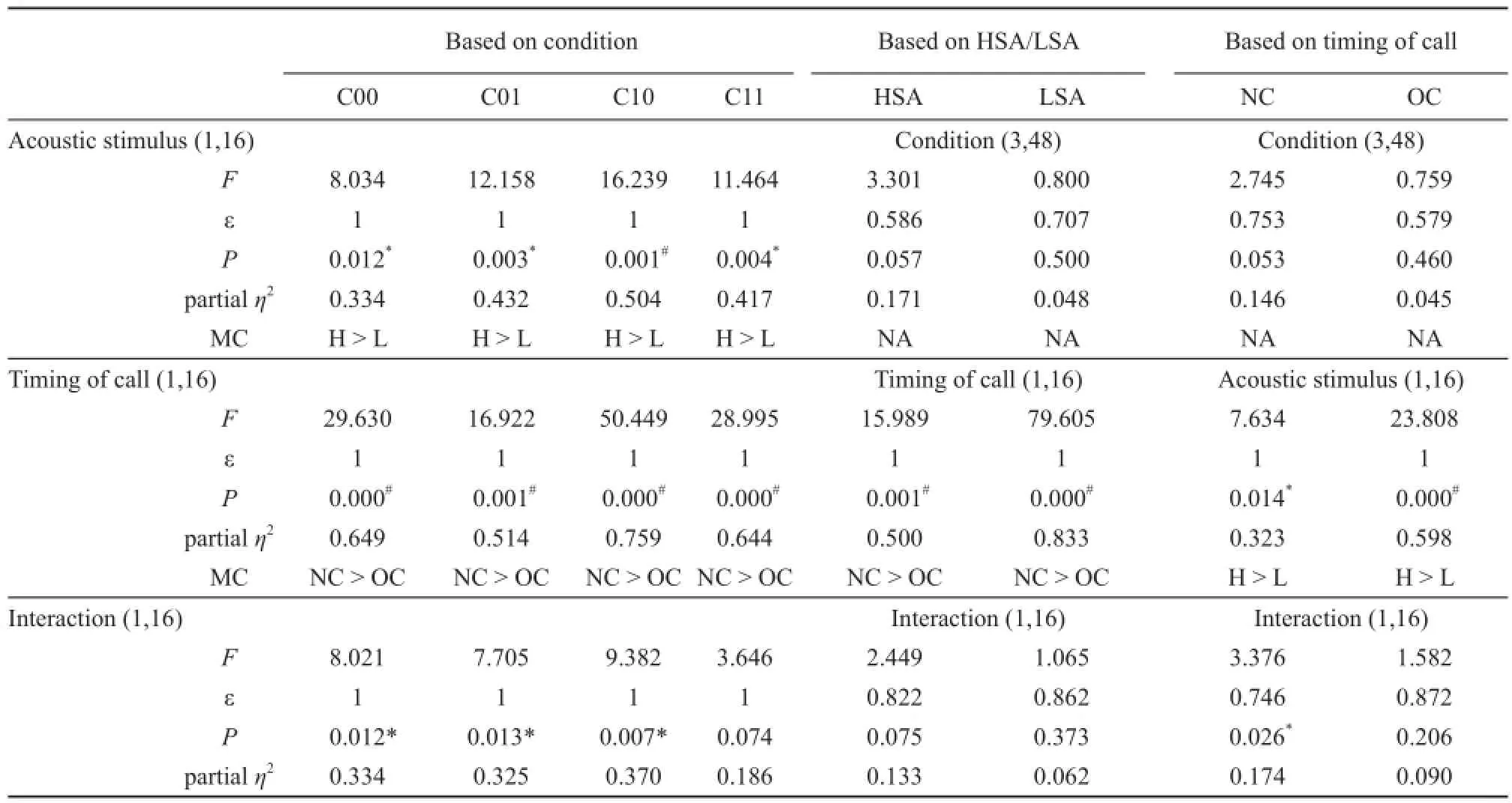

2.5 Statistical analyses Prior to statistical analyses,all values were examined for assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance, using the Shapiro-Wilk W and Levene's tests, respectively. If the values were not normally distributed, they were transformed to square roots because the data were positively skewed (Munro,2005). Within-subject ANOVAs (i.e. repeated measures ANOVAs) were employed with the factors of “condition”and “phase/acoustic stimulus” (see Figure S3) for twoway ANOVA and with the factors “condition”, “acoustic stimulus” and “timing of call” for three-way ANOVA as described below.

The term “condition” refers to the four experimental conditions (C00, C01, C10 and C11) involving antiphonal/ random playbacks of monophonic/stereophonic stimuli(Table 1). The term “phase” refers to the time period before or after the playback stimulus within which the subject's response calls occurred (see Figure S3A). The factor “timing of call” refers to whether the onset of responsive call either overlapped or did not overlap the playback stimulus (see Figure S3B).

Both main effects and interactions were examined. Moreover, one-way repeated measure ANOVA was used with the factor “condition” for determining the grand average of the number of calls produced for each block. Simple or simple-simple effects analysis was applied when the interaction was significant. For significant ANOVAs, data were further analyzed for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction or t-test. Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon (ε) values were employed when the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was necessary. Estimations of effect size were determined with Cohen's d for t-tests and partial η2for ANOVAs (Cohen's d or partial η2= 0.20 is a small effect size, 0.50 is a medium effect size and 0.80 is a large effect size) (Cohen, 1992). SPSS software (release 13.0) was utilized for the statistical analysis. A signifi cance level of P < 0.05 was used in all comparisons.

3. Results

3.1 Leading calls varied with the sequence cue There was no significant difference of the grand average numbers of advertisement calls produced between the four experimental conditions (F3,48= 2.159; ε = 0.624,P = 0.136 > 0.05, partial η2= 0.119), suggesting that the competitive motivation of the subjects was not affected by the experimental design. With respect to the factors “phase” and “condition” both main effects (F3,48= 46.589; ε = 0.571, P = 0.000, partial η2= 0.744 for“phase” and F3,48= 3.013; P = 0.039 < 0.05, partial η2= 0.158 for “condition”) and the interaction (F9,144= 5.769;P = 0.000, partial η2= 0.265) were significant for call numbers.

For the playback stimuli for each experimental condition, the mean numbers of responsive calls produced during the pre-phase (i.e. before the stimulus presentation)was significantly higher than the number of calls produced during the post-phase, although the differences for LSA stimulation in the conditions containing sequence information (i.e. C10 and C11) did not reach statistical signifi cance (Figure 3A and Table 2). The mean number of calls produced prior to presentation of the HSA stimulus (Pre-HSA) was significantly higher than the number of calls produced during the three other phases(Post-HSA, Pre- and Post- LSA) for the experimental conditions with sequence cues (i.e. C10 and C11, P <0.001, Figure 3A and Table 2). During the Pre-HSA or Post-LSA phase in the C10 and C11 conditions in which sequence cues are present, the mean numbers of calls produced in response to the playbacks was signifi cantly higher than in conditions C00 and C01 lacking this cue(P < 0.05), although the difference between C10 andC00 or between C11 and C00 did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3A and Table 2). These results suggested that the subjects could produce leading calls more successfully, especially prior to the HSA playbacks,when the sequence cue was available.

Table 2 Results of simple effect analysis for those calls produced in response to playbacks as a function of the factor “condition”, “phase”and “acoustic stimulus”.

3.2 Non-overlapping call production varied with sequence cues The main effects were significant for“acoustic stimulus” (F1,16= 21.642; ε = 1.0, P = 0.000,partial η2= 0.575) and “timing of call” (F1,16= 46.953; ε = 1.0, P = 0.000, partial η2= 0.746) but not “condition”(F3,48= 1.737; ε = 0.595, P = 0.196 > 0.05, partial η2= 0.098), and the interactions were also signifi cant between“acoustic stimulus” and “timing of call” (F1,16= 16.353;P = 0.001 < 0.05, partial η2= 0.505) and between “acoustic stimulus” and “condition” (F3,48= 3.592; P = 0.020 <0.05, partial η2= 0.183).

In all four conditions, the numbers of non-overlapping calls were significantly higher than the number of overlapping calls for each acoustic stimulus (P < 0.05,Figure 4A and Table 3), implying that male music frogs were capable of interval timing. For the playbacks in conditions in which sequence cues were available (i.e. C10 and C11), the numbers of calls produced in response to HSA calls was signifi cantly higher than those produced in response to LSA calls regardless of whether the response calls were overlapping or non-overlapping (P <0.05, Figure 4A and Table 3). In contrast, for conditions without sequence cues only the numbers of overlapping calls in response to HSA and LSA calls differed signifi cantly. Moreover, in the conditions with sequence cues (C10 and C11), the numbers of non-overlapping calls produced in response to HSA stimulation was significantly higher than in the C01 condition which lacked this cue.

3.3 Calls in response to HSA playbacks varied with sequence and spatial cues For all call responses, the main effects were significant for the factor “acoustic stimulus” (F1,16= 13.608; ε = 1.0, P = 0.002 < 0.05,partial η2= 0.460) but not for the factor “condition” (F3,48= 2.142; ε = 0.627, P = 0.138 > 0.05, partial η2= 0.118),and the interaction was also signifi cant (F3,48= 3.904; ε = 0.640, P = 0.032 < 0.05, partial η2= 0.196).

For all experimental conditions, the number of calls produced in response to HSA playbacks was signifi cantly higher than those produced in response to LSA playbacks(Figure 3B and Table 2). The male frogs produced overlapping advertisement calls in response to repeating HSA and LSA playbacks with about a 300 ms delay.The number of responsive calls competing with the HSA stimulus in conditions with sequence cues available was significantly higher than that in the C01 condition lacking sequence cues (P < 0.05; Figure 3B and Table 2). Furthermore, males preferred competing against HSA calls in comparison to LSA calls when the sequence cue was available so that about 65% and 64% of responsive calls in the C10 and C11 conditions but only 54% and 57% of calls in the C00 and C01 conditions were produced in response to HSA stimulation, suggesting the subjects preferred primarily to compete in terms of vocalizing in response to HSA calls compared to LSA calls when the sequence cue was available.

Table 3 Results of simple effect analysis for those calls produced in response to playbacks as a function of the factors “condition”, “acoustic stimulus” and “timing of call”.

For the number of notes, the main effects were significant for “acoustic stimulus” (F1,16= 10.089; ε = 1.0, P = 0.006 < 0.05, partial η2= 0.387) and “timing of call” (F1,16= 6.841; ε = 1.0, P = 0.019 < 0.05, partial η2= 0.299) rather than “condition” (F3,48= 0.879; ε = 0.710,P = 0.430 > 0.05, partial η2= 0.052), and the interaction was also significant between “acoustic stimulus” and“timing of call” (F1,16= 11.929; P = 0.003 < 0.05, partial η2= 0.427). For LSA playbacks, the number of notes of non-overlapping calls was significantly higher than for overlapping calls (P < 0.001, Figure 4B); while for overlapping calls, the number of notes in response to HSA playbacks was signifi cantly higher than those in response to LSA playbacks (P < 0.05, Figure 4B).

4. Discussion

Vocal competitive patterns in the music frog change dynamically depending on the availability of environmental cues. Males tended to avoid producing advertisement calls which overlapped the acoustic playback stimuli and generally produced calls in advance of the playback stimulus onset. Frogs preferred competing in terms of vocalizing against HSA calls to competing against LSA calls when the temporal sequence cues were available while they competed equally with the two types of stimuli when this cue was unavailable.

gnaling reflects female p

The acoustic environment of a chorus can be complex because of the spatial distribution of males, intense competition for mates, high levels of background noise, and temporal overlap among calls produced by neighboring males (Wells and Schwartz, 2006). Since call overlap may obscure the fine temporal components of male calls (Schwartz, 1987), females generally prefernon-overlapped signals (Amy et al., 2008; Martínez-Rivera and Gerhardt, 2008). Therefore, with respect to the timing of sex displays, theoretically males should adopt a strategy for minimizing the costs and maximizing the probability of mating success (Byrne, 2008). This hypothesis is supported by our results in which the number of non-overlapping calls was signifi cantly higher than that of overlapping calls for both the HSA and LSA acoustic stimuli in each condition.

Previous research (Fang et al., 2014) has shown that Babina males are, as are signalers of some other species(Greenfield, 1994a; b; Greenfield et al., 1997), capable of interval timing and are able to predict the onset of the calls produced by rivals on the basis of inter-stimulus intervals. Furthermore subjects producing a leading call rather than a following call might benefit in intensive male competitions because of the precedence effect,an inherent property of the vertebrate auditory system(Litovsky et al., 1999; Zurek, 1987). Thus the capability of interval timing would theoretically be selected for in species such as Babina in which males compete vocally under these circumstances (Cheng and Crystal, 2008;Crystal, 2006; Fang et al., 2014).

Sexual selection is a co-evolutionary process between males and females (Cotton et al., 2006). Hence, females' preferences would theoretically be reflected by male dynamic competitive strategies. For music frogs, about two thirds of females choose resident or dominant males producing HSA calls as mates (Cui et al., 2012) and a similar percentage of male competitive vocalizations are directed against HSA calls in the fi eld (Fang et al., 2014). These findings are consistent with the idea that male competitive strategy is dependent on predictable female preferences in Babina. Furthermore, the number of notes per overlapping call produced in response to LSA calls was signifi cantly less than for HSA calls. For this reason we submit that the proportion of advertisement calls produced by males in response to HSA calls may be used as a reliable index refl ecting effective competition among males.

4.2 Sequence vs. spatial cues in male music frog call production Territorial animals typically respond less aggressively to neighbors than to strangers on the basis of identity cues including spatial cue. This “dear enemy phenomenon” has been reported in mammals (Rosell and Bjørkøyli, 2002; Zenuto, 2010), birds (Briefer et al.,2010; 2008), lizards (Carazo et al., 2008), fish (Leiser,2003; Leiser et al., 2006) and ants (Dimarco et al., 2010). Some anuran species including American bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana), green frogs (R. clamitans), agile frogs (R. dalmatina) and Concave-Eared frogs (Odorrana tormota)have also been reported to use acoustic and location cues to discriminate neighbors which are then accepted as“dear enemies” rather than strangers who are attacked(Bee, 2004; Bee and Gerhardt, 2001a; Bee and Gerhardt,2001b; Bee and Gerhardt, 2001c; Davis, 1987; Feng et al., 2009; Lesbarrères and Lodé, 2002; Owen and Perrill,1998).

Time and space for displays in the chorus lek are highly competitive resources. Information concerning the availability of these resources may be encoded in the vocalizations of the male participants in form of sequence and interaural cues. However, whether males rely more on sequence or spatial cues remains largely unknown. Male music frogs build burrows along pond edges for mating, egg-laying and tadpole development, producing advertisement calls inside the burrow (Cui et al., 2010),and do not move away until mating successfully. For this reason, males might ignore information about the locations of other males during vocal competition since the burrow cannot move, as has been reported in studies(Carlyon and Gockel, 2007; Darwin, 2007).

In the present study Babina males mainly used sequence cues to increase competitive effectiveness by altering precisely the timing of calls. This finding is consistent with the fact that in their natural environment Babina males almost call from fi xed locations, i.e. their burrows. Moreover, more advertisement calls were produced in response to HSA calls in the experimental conditions in which sequence cues were available than in those which did not provide sequence cues. Spatial cues generally play a minor role in grouping or segregating auditory signals (Carlyon and Gockel, 2007; Darwin,2007), although anurans show remarkable sound localization ability in undisturbed sound fi elds (Feng and Schellart, 1999; Gerhardt and Huber, 2002). This would explain why Babina males apparently allocate competitive efforts effectively on the basis of the perceived sexual attractiveness of rivals when sequence but not spatial cues are available (Figure 3A and 4A). In addition, the patterns of call-timing in response to two stimuli of playback were similar across males in each condition (Figure S4, supplementary material), indicating that the same competitive strategy was adopted in vocally competition for all males, i.e. dependent more on sequence cues.

4.3 Probable mechanisms of call timing Studies of call timing have shown that signalers adjust the timing of their call activities relative to those of other signalers,resulting in either synchrony or alternation (Reichert,2012). Both homoepisodic and proepisodic modelshave been proposed as mechanisms underlying these rhythmicity patterns (Greenfi eld, 1994a; b; Greenfi eld et al., 1997). The homoepisodic model applies primarily to nonrhythmic species in which individuals respond in a rapid and immediate manner at the onset of a concurrent sound (Greenfield, 1994a). In contrast, the proepisodic model applies to rhythmically signaling species in which the timing of an individual's response to the concurrent stimulus is modulated by a previous stimulus (Greenfi eld,1994a; b; Greenfi eld et al., 1997).

Babina males engage in competition in the form of both synchrony and alternation, consistent with the idea that the proepisodic model is most applicable. Phase delay mechanisms have been proposed for the proepisodic model (Greenfield, 1994a; b), in which signalers adjust call periods on a call-by-call basis in response to the relative timing of an external stimulus (Buck, 1988)and which produce both alternation and synchrony(Greenfield, 2002; 2005). This model proposes a neural mechanism which resets a male's call timing following perception of another male's call. The rate of recovery from inhibition determines when the male resumes calling, and the ratio between the recovery rate and the call period of the external stimulus largely determines whether synchrony or alternation results (Greenfield,1994a; b). Thus males who use such an inhibitoryresetting phase delay mechanism could theoretically produce leading calls, which would attract females,because they exploit the inherent precedence effect of the auditory system (Greenfi eld et al., 1997).

Male frogs produced fewer overlapping advertisement calls in response to repeating LSA than to HSA playbacks with about a 300 ms delay after stimuli onset. This behavioral result is similar to the attention-dependent“voice-specific response” peaking at 320 ms in humans(Levy et al., 2001; 2003). Greenfield (1994) has shown that the effector delay (i.e. the time interval between the trigger from the central nervous system and vocal signal onset) ranges from 50-200 ms in insects (Greenfield,1994b). Thus it is reasonable to speculate that males' call timing could be reset by the onset of playbacks and animals could accomplish call identifi cation within around 200 ms. This prediction is consistent with our pilot study that showed vocalizations discrimination occurs within~100 ms while call identifi cation is accomplished around~200 ms using event-related potentials (ERP) technology in the same species (unpublished data).

The phase delay model assumes that the male's hearing is infl uenced by selective attention to the nearest or loudest neighbor in the chorus where many rivals attend to one another (Greenfield, 1994a; b; Greenfield et al., 1997). This assumption has been verified by the works on selective attention in some frog species (Bates et al., 2010; Brush and Narins, 1989; Greenfield and Rand, 2000; Schwartz, 1993). However, the results of the present and previous studies (Fang et al., 2014) indicate that males pay attention mainly to signals related closely to predictable female preferences, and not mainly to the nearest or loudest calls. In addition, the call timing of Babina males has been shown to depend on the biological significance of stimuli, sexual attractiveness of rivals and levels of competitive pressure (Fang et al., 2014),suggesting that call timing is determined by multiple variables. Therefore, future studies should consider the possible involvement of other variables such as dynamic attention modulation in the determination of call timing.

Acknowledgements This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31372217 to Guangzhan Fang and No. 31270042 to Jianguo Cui), from the Youth Professor Project of Chengdu Institute of Biology (Y3B3011) and Youth Innovation Promotion Association of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Y2C3011, KSCX2-EW-J-22) to Jianguo Cui. Animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chengdu Institute of Biology.

References

Amy M., Monbureau M., Durand C., Gomez D., Théry M., Leboucher G. 2008. Female canary mate preferences:differential use of information from two types of male-male interaction. Anim Behav, 76(3): 971-982

Bates M. E., Cropp B. F., Gonchar M., Knowles J., Simmons J. A., Simmons A. M. 2010. Spatial location influences vocal interactions in bullfrog choruses. J Acoust Soc Am, 127(4):2664-2677

Bee M. A. 2004. Within-individual variation in bullfrog vocalizations: Implications for a vocally mediated social recognition system. J Acoust Soc Am, 116(6): 3770-3781

Bee M. A. 2015. Treefrogs as animal models for research on auditory scene analysis and the cocktail party problem. Int J Psychophysiol, 95: 216-237

Bee M. A., Gerhardt H. C. 2001a. Habituation as a mechanism of reduced aggression between neighboring territorial male bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana). J Comp Psychol, 115(1): 68-82

Bee M. A., Gerhardt H. C. 2001b. Neighbour-stranger discrimination by territorial male bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana):I. Acoustic basis. Anim Behav, 62(6): 1129-1140

Bee M. A., Gerhardt H. C. 2001c. Neighbour-stranger discrimination by territorial male bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana):II. Perceptual basis. Anim Behav, 62(6): 1141-1150

Briefer E., Rybak F., Aubin T. 2008. When to be a dear enemy:fl exible acoustic relationships of neighbouring skylarks, Alauda arvensis. Anim Behav, 76(4): 1319-1325

Briefer E., Rybak F., Aubin T. 2010. Are unfamiliar neighbours considered to be dear-enemies? PLoS ONE, 5(8): e12428

Brush J. S., Narins P. M. 1989. Chorus dynamics of a neotropical amphibian assemblage: comparison of computer simulation and natural behaviour. Anim Behav, 37: 33-44

Buck J. 1988. Synchronous rhythmic fl ashing of fi refl ies. II. Q Rev Biol: 265-289

Byrne P. G. 2008. Strategic male calling behavior in an Australian terrestrial toadlet (Pseudophryne bibronii). Copeia, 2008(1):57-63

Carazo P., Font E., Desfilis E. 2008. Beyond ‘nasty neighbours' and ‘dear enemies'? Individual recognition by scent marks in a lizard (Podarcis hispanica). Anim Behav, 76(6): 1953-1963

Carlyon R. P., Gockel H. E. 2007. Effects of harmonicity and regularity on the perception of sound sources. In: Yost W. A.,Popper A. N. and Fay R. R. (eds.) Auditory perception of sound sources. Springer. p 191-213

Cheng K., Crystal J. 2008. Learning to time intervals. In: Menzel R. (ed.) Learning theory and behavior: A Comprehensive Reference No. 1. Academic Press, Oxford. p 341-364

Cohen J. 1992. A power primer. Psychol Bull, 112(1): 155-159

Cotton S., Small J., Pomiankowski A. 2006. Sexual selection and condition-dependent mate preferences. Curr Biol, 16(17): R755-765

Crystal J. D. 2006. Animal behavior: timing in the wild. Curr Biol,16(7): R252-R253

Cui J. G., Tang Y. Z., Narins P. M. 2012. Real estate ads in Emei music frog vocalizations: female preference for calls emanating from burrows. Biol Lett, 8(3): 337-340

Cui J. G., Wang Y. S., Brauth S. E., Tang Y. Z. 2010. A novel female call incites male-female interaction and male-male competition in the Emei music frog, Babina daunchina. Anim Behav, 80: 181-187

Darwin C. J. 2007. Spatial hearing and perceiving sources. In: Yost W.A., Popper A.N. and Fay R.R. (eds.) Auditory perception of sound sources. Springer, New York. p 215-232

Davis M. S. 1987. Acoustically mediated neighbor recognition in the North American bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 21(3): 185-190

Dimarco R. D., Farji-Brener A. G., Premoli A. C. 2010. Dear enemy phenomenon in the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex lobicornis: behavioral and genetic evidence. Behav Ecol, 21(2):304-310

Fang G. Z., Jiang F., Yang P., Cui J. G., Brauth S. E., Tang Y. Z. 2014. Male vocal competition is dynamic and strongly affected by social contexts in music frogs. Anim Cogn, 17(2): 483-494

Farris H., Rand A. S., Ryan M. J. 2005. The effects of time, space and spectrum on auditory grouping in túngara frogs. J Comp Physiol A, 191(12): 1173-1183

Farris H. E., Rand A. S., Ryan M. J. 2002. The effects of spatially separated call components on phonotaxis in túngara frogs:evidence for auditory grouping. Brain Behav Evol, 60: 181-188

Feng A. S., Arch V. S., Yu Z., Yu X. J., Xu Z. M., Shen J. X. 2009. Neighbor-Stranger Discrimination in Concave-Eared Torrent Frogs, Odorrana tormota. Ethology, 115(9): 851-856

Feng A. S., Schellart N. A. 1999. Central auditory processing in fi sh and amphibians Comparative hearing: fi sh and amphibians. Springer, New York. p 218-268

Feng A. S., Schul J. 2006. Sound processing in real-world environments. In: Narins P. M., Feng A. S., Fay R. R. and Popper A. N.(eds.) Hearing and sound communication in amphibians. Springer Verlag, New York. p 323-350

Gentner T. Q. 2007. Mechanisms of temporal auditory pattern recognition in songbirds. Language learning and development,3(2): 157-178

Gerhardt H. C. 1988. Acoustic properties used in call recognition by frogs and toads. In: Fritszch B., Wilczynski W., Ryan M. J.,Hetherington T. E. and Walkowiak W. (eds.) The evolution of the amphibian auditory system. Wiley, New York. p 275-294

Gerhardt H. C., Bee M. A. 2006. Recognition and localization of acoustic signals. In: Narins P. M., Feng A. S., Fay R. R. and Popper A. N.(eds.) Hearing and sound communication in amphibians. Springer, New York. p 113-146

Gerhardt H. C., Huber F. 2002. Acoustic communication in insects and anurans: common problems and diverse solutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Gerhardt H. C., Roberts J. D., Bee M. A., Schwartz J. J. 2000. Call matching in the quacking frog (Crinia georgiana). Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 48(3): 243-251

Greenfi eld M. D. 1994a. Cooperation and confl ict in the evolution of signal interactions. Annu Rev Ecol Syst, 25: 97-126

Greenfi eld M. D. 1994b. Synchronous and alternating choruses in insects and anurans: common mechanisms and diverse functions. Am Zool, 34(6): 605-615

Greenfield M. D. 2002. Signalers and receivers: mechanisms and evolution of arthropod communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Greenfi eld M. D. 2005. Mechanisms and evolution of communal sexual displays in arthropods and anurans. Adv Stud Behav, 35:1-62

Greenfield M. D., Rand A. S. 2000. Frogs have rules: selective attention algorithms regulate chorusing in Physalaemus pustulosus (Leptodactylidae). Ethology, 106(4): 331-347

Greenfield M. D., Tourtellot M. K., Snedden W. A. 1997. Precedence effects and the evolution of chorusing. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 264(1386): 1355-1361

Hurly T. A., Ratcliffe L., Weisman R. 1990. Relative pitch recognition in white-throated sparrows, Zonotrichia albicollis. Anim Behav, 40(1): 176-181

Leiser J. K. 2003. When are neighbours ‘dear enemies' and when are they not? The responses of territorial male variegated pupfish, Cyprinodon variegatus, to neighbours, strangers and heterospecifi cs. Anim Behav, 65(3): 453-462

Leiser J. K., Bryan C. M., Itzkowitz M. 2006. Disruption of dear enemy recognition among neighboring males by female leon springs pupfi sh, Cyprinodon bovinus. Ethology, 112(5): 417-423

Lesbarrères D., Lodé T. 2002. Variations in male calls and responses to an unfamiliar advertisement call in a territorial breeding anuran, Rana dalmatina: evidence for a “dear enemy”effect. Ethol Ecol Evol, 14(4): 287-295

Levy D. A., Granot R., Bentin S. 2001. Processing specificity for human voice stimuli: electrophysiological evidence. Neuroreport, 12(12): 2653-2657

Levy D. A., Granot R., Bentin S. 2003. Neural sensitivity tohuman voices: ERP evidence of task and attentional infl uences. Psychophysiology, 40(2): 291-305

Litovsky R. Y., Colburn H. S., Yost W. A., Guzman S. J. 1999. The precedence effect. J Acoust Soc Am, 106: 1633-1654

Lohr B., Weisman R., Nowicki S. 1994. The role of pitch cues in song recognition by Carolina chickadees (Parus carolinensis). Behaviour, 130(1-2): 1-15

Marshall V. T., Gerhardt H. C. 2010. A precedence effect underlies preferences for calls with leading pulses in the grey treefrog, Hyla versicolor. Anim Behav, 80(1): 139-145

Martínez-Rivera C. C., Gerhardt H. C. 2008. Advertisement-call modification, male competition, and female preference in the bird-voiced treefrog Hyla avivoca. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 63(2):195-208

Meckenhäuser G., Hennig R. M., Nawrot M. P. 2013. Critical Song Features for Auditory Pattern Recognition in Crickets. PLoS ONE, 8(2): e55349

Munro B. H. 2005. Statistical methods for health care research. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Owen P. C., Perrill S. A. 1998. Habituation in the green frog, Rana clamitans. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 44(3): 209-213

Popper A. N., Fay R. R. 2005. Sound source localization. New York: Springer

Reichert M. S. 2012. Call timing is determined by response call type, but not by stimulus properties, in the treefrog Dendropsophus ebraccatus. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 66(3): 433-444

Rose G. J., Gooler D. M. 2006. Function of the amphibian central auditory system. In: Narins P. M., Feng A. S., Fay R. R. and Popper A. N.(eds.) Hearing and Sound Communication in Amphibians. Springer, New York. p 250-290

Rosell F., Bjørkøyli T. 2002. A test of the dear enemy phenomenon in the Eurasian beaver. Anim Behav, 63(6): 1073-1078

Schwartz J. J. 1987. The function of call alternation in anuran amphibians: a test of three hypotheses. Evolution, 41: 461-471

Schwartz J. J. 1993. Male calling behavior, female discrimination and acoustic interference in the Neotropical treefrog Hyla microcephala under realistic acoustic conditions. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 32(6): 401-414

Schwartz J. J., Buchanan B. W., Gerhardt H. C. 2001. Female mate choice in the gray treefrog (Hyla versicolor) in three experimental environments. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 49(6): 443-455

Vedenina V. Y., Pollack G. S. 2012. Recognition of variable courtship song in the fi eld cricket Gryllus assimilis. J Exp Biol,215(13): 2210-2219

Wells K., Schwartz J. 2006. The behavioral ecology of anuran communication. In: Narins P. M., Feng A. S., Fay R. R. and Popper A. N. (eds.) Hearing and Sound Communication in Amphibians. Springer Verlag, New York. p 44-86

Wilczynski W., Endepols H. 2006. Central auditory pathways in anuran amphibians: the anatomical basis of hearing and sound communication. In: Narins P. M., Feng A. S., Fay R. R. and Popper A. N.(eds.) Hearing and sound communication in amphibians. Springer, Berlin, Germany. p 221-249

Yost W. A. 2007. Perceiving sound sources. In: Yost W. A.,Popper A. N. and Fay R. R. (eds.) Auditory Perception of Sound Sources. Springer, New York. p 1-12

Zenuto R. R. 2010. Dear enemy relationships in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum: the role of memory of familiar odours. Anim Behav, 79(6): 1247-1255

Zurek P. M. 1987. The precedence effect. In: Yost W.A. and Gourevitch G. (eds.) Directional hearing. Springer-Verlag, New York. p 85-105

s: Dr. Guangzhan Fang, from Chengdu Institute of Biology (CIB), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Chengdu,China, with his research focusing on neurobiology and cognition of amphibians; Prof. Yezhong Tang, from CIB, CAS, Chengdu, China, with his research focusing on neurobiology of amphibians and reptiles.

E-mail: fanggz@cib.ac.cn (G. Z. FANG); tangyz@cib.ac.cn (Y. Z. TANG)

13 April 2015 Accepted: 14 September 2015

杂志排行

Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- Catalogue of the Type Specimens of Amphibians and Reptiles in the Herpetological Museum of the Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences: IV. Lizards (Reptilia, Sauria)

- Rediscovery of Microgecko helenae fasciatus (Schmidtler and Schmidtler, 1972) from Kermanshah Province, Western Iran with Notes on Taxonomy, Morphology, and Habitat

- Genetic Structure and Relationships among Populations of the Caspian Bent-toed Gecko, Tenuidactylus caspius (Eichwald, 1831)(Sauria: Gekkonidae) in Northern Iran

- Structure and Function of the Gastrointestinal Tract of the Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas) Hatchling

- Significant Male Biased Sexual Size Dimorphism in Leptobrachium leishanensis

- Variation and Sexual Dimorphism of Body Size in the Plateau Brown Frog along an Altitudinal Gradient