Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver: sonographic and CT fndings

2015-02-07

Shanghai, China

Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver: sonographic and CT fndings

Qing Lu, Hui Zhang, Wen-Ping Wang, Yun-Jie Jin and Zheng-Biao Ji

Shanghai, China

BACKGROUND:A preoperative diagnosis of primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) can have profound therapeutic and prognostic implications. Because of the rarity of PHL, however, there are few reports on diagnostic imaging. We reviewed the clinical and radiologic fndings of 29 patients with PHL, the largest series to date, to evaluate the diagnostic features of this disease.

METHODS:Clinical data and radiologic fndings at presentation were retrospectively reviewed for 29 patients with pathologically confrmed PHL from January 2005 to June 2013. Imaging studies, including ultrasound (US) (n=29) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) (n=24), were performed within 2 weeks before biopsy or surgery.

RESULTS:Among the 29 patients, 23 (79%) were positive for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and 26 (90%) had a signifcantly elevated level of serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). There were two distinct types of PHL on imaging: diffuse (n=5) and nodular (n=24). Homogeneous or heterogeneous hepatomegaly was the only sign for diffuse PHL on both US and CECT, without any defnite hepatic mass. For the nodular type, 63% (15/24) of patients had solitary lesions and 38% (9/24) had multiple lesions. On US, seven patients displayed patchy distribution with an indistinct tumor margin and a rich color fow signal. CECT showed rim-like enhancement (n=3) and slightly homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement (n=14) in the arterial phase and isoenhancement (n=5) and hypoenhancement (n=12) in the portal venous and late phases. Furthermore, in fve patients, CT revealed that hepatic vessels passed through the lesions and were not displaced from the abnormal area or appreciably compressed.

CONCLUSIONS:The infltration type of PHL was associated with the histologic subtype. Considered together with HBV positivity and elevated LDH, homogeneous or heterogeneous hepatomegaly may indicate diffuse PHL, whereas patchy distribution with a rich color fow signal on US or normal vessels extending through the lesion on CECT may be the diagnostic indicators of nodular PHL.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2015;14:75-81)

computed tomography;sonography; lymphoma; primary tumor; liver

Introduction

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL), a type of lymphoma that is confned to the liver without infltration of other lymphoid structures, is a very rare entity that was frst reported in 1976[1]and accounts for fewer than 1% of all extra-nodular lymphomas.[2,3]There are three main morphologic patterns of PHL: solitary nodule (60%), multiple focal nodules (35%), and diffuse infltrating without nodular formation (5%).[4,5]Chemotherapy is the frst-line treatment for lymphoma. Although there are a few reports on imaging diagnosis of PHL, characteristic imaging features that allow a defnite diagnosis are not available. Diagnostic imaging could have profound therapeutic and prognostic implications, such as preventing unnecessary surgery or biopsy. We retrospectively reviewed clinical data and imaging fndings for 29 patients with PHL to analyze the diagnostic features of this disease. To our knowledge, this is the largest series of patients that has been studied to date with respect to imaging diagnosis of PHL.

Methods

Patients

In our institution, PHL was pathologically confrmedin 29 patients between January 2005 and June 2013. Inclusion criteria adapted were as previous published:[6](1) symptoms at the time of diagnosis caused mainly by liver involvement; (2) absence of palpable lymphadenopathy and no radiologic evidence of distant lymphadenopathy; and (3) absence of leukemic blood involvement in the peripheral blood smear.

Twenty-nine patients met these criteria and were enrolled in our study. Ultrasound (US) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) were performed in 29 and 24 patients respectively. Because of the small number of patients receiving magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (n=3) or [18F]-fuorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) (n=2), only US and CECT features were analyzed in our study. However, information from all imaging modalities was used in the differentiation of primary or secondary hepatic lymphoma. None of the patients had evidence of other primary or secondary hepatic neoplasm. The Ethics Committee of our institution approved this study. Informed consent for publication of this study was obtained from all surviving patients. In the majority of patients, the clinical data were obtained at the time of the patient's frst clinical presentation.

Imaging interpretation

Radiologic examinations prior to pathologic diagnosis, including US and CT, were performed within 2 weeks before ultrasound-guided biopsy or surgery. US examination was conducted with one of the following three real-time scanners: DU8 (CA430E 5-2, 2-5 MHz; Esaote Clinical Solutions, Italy); IU22 (C5-1, 1-5 MHz; Philips Medical Systems, the Netherlands); and Medison Accuvix V10 (C3-7IM, 2-5 MHz; Samsung Medison, Korea). CECT was performed with one of the following three CT scanners: Marconi 8000 (Philips Medical Systems, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Lightspeed 64 (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, USA), and Somatom defnition 64 (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany). Cine clips of the real-time US examination were recorded on hard disc. For CECT, 120-140 mL of iodinated intravenous contrast medium was administered at a rate of 3.0 mL/s in all cases. Up to four scans at different phases of contrast accumulation were acquired: native scan, early arterial phase (15-25 s after injection), early venous phase (35-45 s), and late venous phase (90-110 s). Typical imaging parameters were 120 kVp, 150-300 mA, and 5.0-mm slice thickness with a pitch of 0.6. Two experienced radiologists reviewed the cine clips of US and the CECT images to evaluate the imaging appearance of the liver and the number, size, location, margin, echogenicity/density, and color fow signal of the lesions, as well as the enhancement features during CECT. Differences in imaging interpretations were resolved by discussion, and the fnal interpretation was based on a consensus of the two readers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Parametric data were presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between the pathology and imaging infltration, tumor margin and tumor size were performed using the Chisquare test. APvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically signifcant.

Results

Clinical and laboratory data

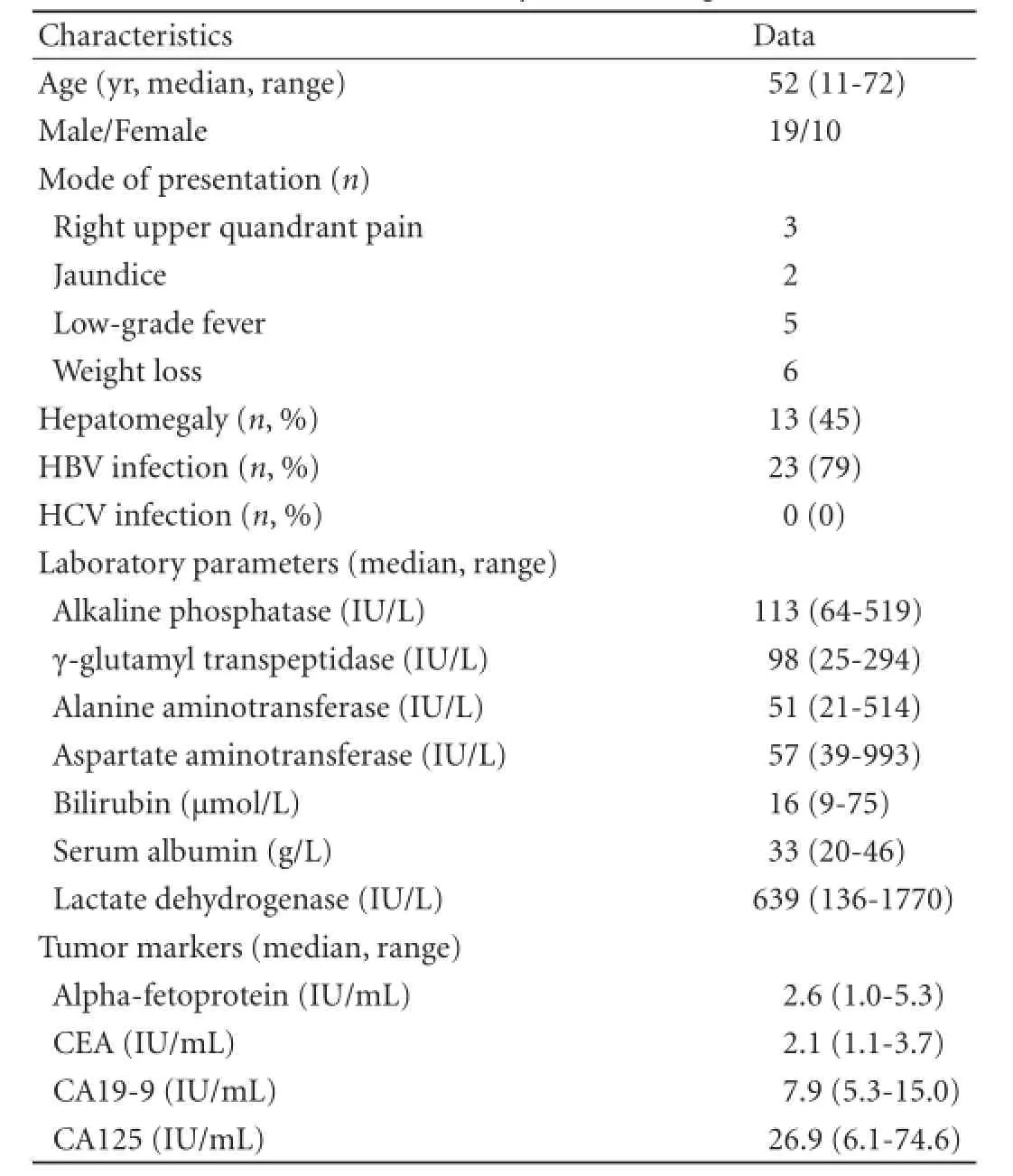

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. Twenty-three patients (79%) were positive for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and 26 (90%) had signifcantly elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). None of the cases had immunodefciency or au-toimmune disease. Bone marrow biopsy showed no lymphoma infltration.

Table 1.Clinical and laboratory data of the patients (n=29)

Imaging appearance

The initial abdominal examination showed two morphologic patterns: diffuse (n=5) and nodular type (single or multiple) (n=24).

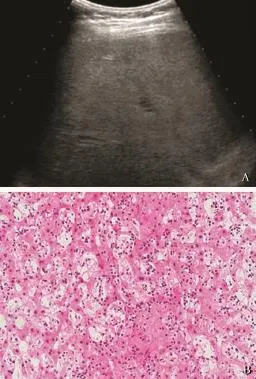

Fig. 1.A: conventional ultrasonography showing heterogeneous hepatomegaly without any defnite hepatic masses. The pathology with biopsy showing a hepatosplenic lymphoma;B: histological photograph of diffuse T-cell primary hepatic lymphoma indicating diffuse infltration of small- to median-sized lymphoma cells (HE, original magnifcation ×100).

All fve diffuse PHLs were imaged by US and CT. In four cases, diffuse homogeneous hepatomegaly was the only sign on image examination, without any type of definite hepatic mass (Figs. 1 and 2). No intrahepatic portal venous thrombus or biliary dilation was observed on US, and CT demonstrated the normal course of hepatic vessels with no compression, distortion, or occlusion. In the ffth case, both US and CT revealed heterogeneous hepatomegaly with sporadic irregular hypoechoic/low-density areas scattered throughout the whole liver. After administration of contrast agent, no enhancement was detected within the low-density areas, leading to the diagnosis of infammation or necrosis on CECT.

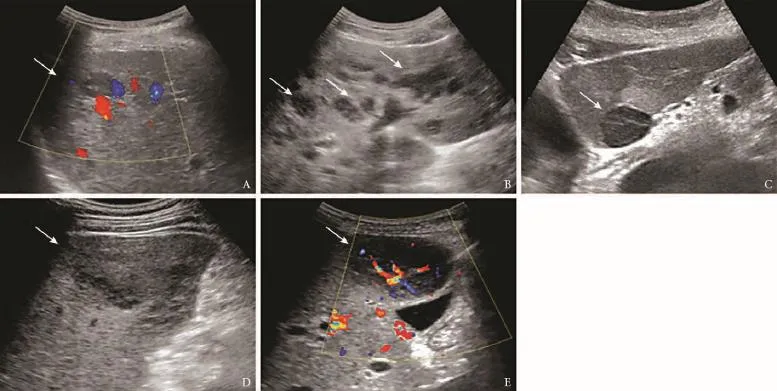

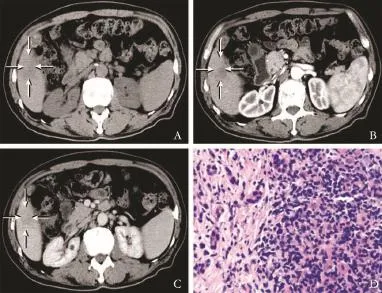

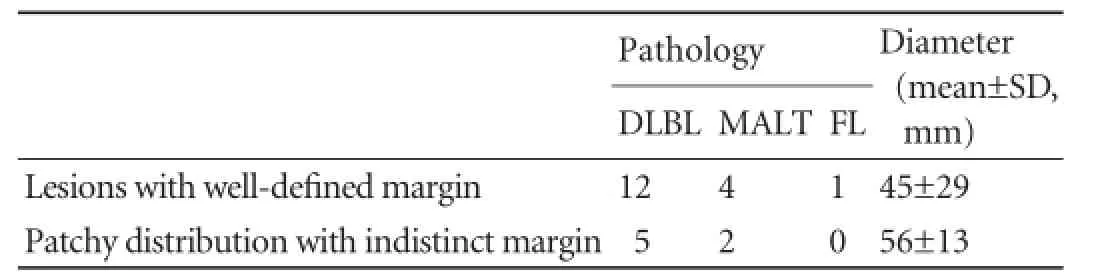

Among the 24 nodular PHLs, a solitary nodule (range 1.2-13.3 cm; mean±SD 4.7±2.8 cm) (Fig. 3A) was observed in 15 patients and multiple nodules (range 1.0-8.4 cm, mean±SD 3.3±1.7 cm) (Fig. 3B) in 9 patients. The lesions were homogeneous hypoechoic (n=20) or isoechoic (n=4), and either round or oval with a welldefned margin (n=17) (Fig. 3C) or showed patchy distribution with an indistinct margin (n=7) (Fig. 3D). A strong perilesional or intralesional color fow signal was detected on color Doppler fow imaging (CDFI) (n=19) (Fig. 3E). Nineteen nodular PHLs underwent CT examination and all of the lesions were low density with well-defned (n=14) or indistinct (n=5) margins (Fig. 4). After administration of contrast agent, rim-like enhancement (n=3) and slight homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement (n=14) were observed in the arterial phase, and during the portal venous and late phases 5 lesions showed isoenhancement and 12 hypoenhancement (Fig. 4). In the remaining two patients, no enhancement of the lesions was detected. Furthermore, on CT images of fve patients, the hepatic vessels extended through the lesion without evidence of compression or deviation.

Pathology

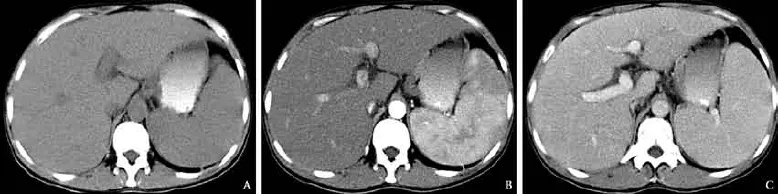

Fig. 2.Computed tomography (CT) of diffuse peripheral T-cell lymphoma.A: unenhanced CT showing hepatomegaly with no change of hepatic density;B,C: contrast-enhanced CT revealing no enhanced masses throughout the phase of enhancement and the normal course of hepatic vessels with no compression, distortion or occlusion (B: arterial phase;C: portal venous phase).

Fig. 3.Ultrasonographic images of primary hepatic lymphoma.A: single nodule with no color fow signal;B: multiple nodules;C: a well-defned lesion;D: a lesion with patchy distribution with an indistinct margin;E: a rich color fow signal revealed by CDFI.

Fig. 4.Computed tomography (CT) of primary hepatic lymphoma.A: a 61×40 mm hypo-attenuation lesion detected in the right lobe of the liver with obscure boundary;B,C: on contrast-enhanced CT, the lesion showing a heterogeneously patchy enhancement in the arterial phase and the enhancement degree was higher in the portal venous phase than that in the arterial phase;D: histological photograph of nodular B-cell primary hepatic lymphoma showing sinusoidal infltration of median-sized lymphoma cells (HE, original magnifcation ×100).

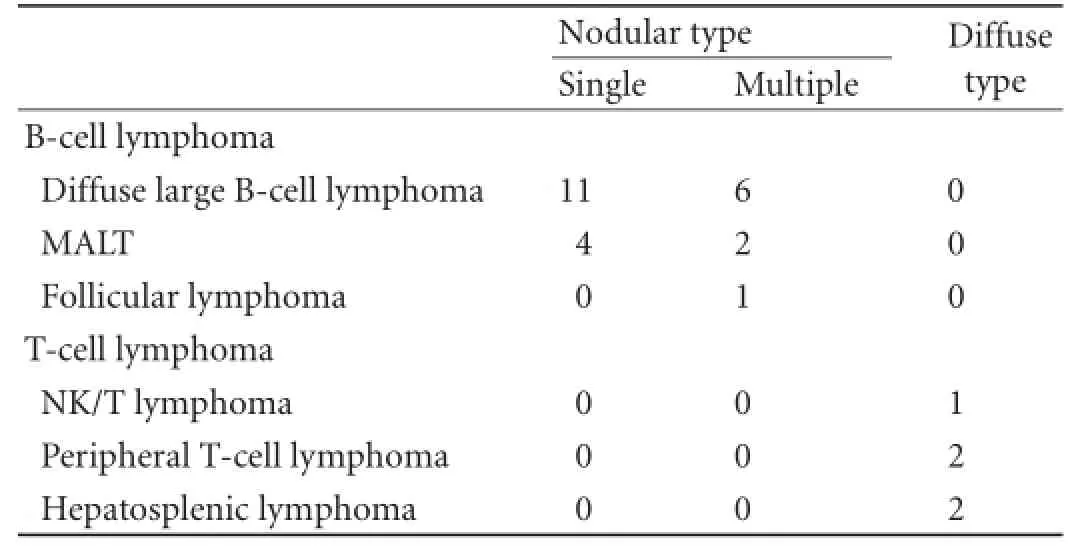

The pathological fndings are summarized in Table 2. Histologic specimens were acquired by surgery (n=9) or by ultrasound-guided biopsy with an automatic 18-gauge biopsy needle (Magnum, BARD, USA) (n=20). Because no defnite focal mass was evident in diffuse PHLs, the transjugular liver biopsy approach was adopted in these patients. With respect to the liver infltration type, all the B-cell lymphomas appeared as nodular typewhereas the T-cell lymphomas appeared only as diffuse type (P<0.001). However, there was no signifcant difference among the different subtypes of B-cell lymphoma when comparing solitary and multiple nodular infltra-tion. As shown in Table 3, there was no signifcant difference between well-defned lesions and patchy distributed lesions with respect to pathology and mean diameter (P=0.214 and 0.206, respectively).

Table 2.The relationship between different subtypes of PHL and imaging appearance

Table 3.Comparison of different appearance of nodules

Prognosis

With the exception of one patient with diffuse PHL who died from hepatic failure 12 days after liver biopsy, all of the patients received chemotherapy or surgery as primary treatment. Among the fve patients with diffuse PHL, two remained in complete remission after a median follow-up of 12 months, two died at 12 and 42 days of follow-up, respectively, and one was lost to follow-up. Among the 24 patients with nodular PHL, 9 patients who received surgical treatment remained tumor-free after a median follow-up of 12 months (range 7-15). Among the 15 patients who were treated with chemotherapy, 8 achieved a complete response, 3 had a partial response and were alive after a median follow-up of 9 months (range 4-13), and the other 4 were lost to follow-up.

Discussion

PHL is a very rare entity that usually presents during middle age, predominantly in the male population.[7]Patients with PHL typically have abnormal liver function, and the presence of an elevated level of LDH with normal values of α-fetoprotein (AFP) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) remains a valuable biologic feature of PHL.[8]The exact cause of PHL is unknown, although viruses such as HBV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Epstein-Barr virus have been implicated.[9]A strong association was noted between PHL and HBV in our study, which is consistent with a previous report.[10]However, the possible role of HBV in lymphomagenesis remains uncertain. None of the patients in our study was positive for HCV. In our study, three main morphologic patterns of PHL were observed: solitary mass (52%, 15/29), multiple focal nodules (31%, 9/29), and diffuse infltrating without nodular formation (17%, 5/29). There is a paucity of published case reports concerning the imaging diagnosis of diffuse PHL. Gupta et al[11]described US imaging features of a diffuse PHL with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma as heterogeneous hepatomegaly without any type of lesion. Kang et al[12]reported CT imaging of a diffuse PHL as diffusely decreased hepatic attenuation that mimicked hepatitis and was undistinguishable from fatty infltration. In our series, homogeneous hepatomegaly with no change in echogenicity or density was the only sign on US and CT in four patients with diffuse PHL. Histologically, diffusing infltration of the tumor cells preponderates the portal or sinusoidal tissue without nodular infltration, which may account for the diffuse type with no defnite hepatic masses.[13]In the remaining patients with diffuse disease, there were no imaging changes on US or CT other than heterogeneous hepatomegaly. However, hepatomegaly, either homogeneous or heterogeneous, is a common complication of other diseases such as congestive heart failure, Budd-Chiari syndrome, or fatty liver, and is not a specifc diagnostic feature of PHL. Therefore, there was no pathognomonic imaging pattern on either US or CT that could be used for defnite diagnosis of diffuse PHL.

In our series, all of the T-cell PHLs were diffuse type, whereas all of the B-cell PHLs were the nodular type. Furthermore, we reviewed 19 previously reported cases of primary hepatic T-cell lymphoma,[1,2,14-21]of which 17 were diffuse type and the remaining 2 were nodular type. Thus we hypothesize that there might be some correlation between the pathologic subtype of PHL and its infltration type. The reason for this is not clear, and should be further studied with a larger number of cases. Stancu et al[14]reported that primary hepatic T-cell lymphoma has a worse prognosis than B-cell lymphoma; however, they did not mention the infltration type. Emile et al[22]showed a signifcant difference between the 1- and 3-year survivals of nodular PHL (70% and 57%) and those of diffuse PHL (38% and 18%) (P=0.003), but they did not describe the pathologic subtype of PHL. In our study, the prognosis of different infltration types of PHL was inconclusive because of the small number of patients with diffuse PHL and the incomplete follow-up. However, two patients who died during follow-up had diffuse PHL. This might in part be related to the delay in diagnosis because of the non-specifc clinical and imaging presentations. If diffuse PHL is suspected based on clinical hepatobiliary symptoms, an elevated level of LDH, and imaging of homogeneous or heterogeneous hepatomegaly, a liver biopsy should be performed to confrm the diagnosis.

In our series, nodular infltration was observed in 24 patients. Irrespective of whether the lesions were solitary or multiple, hypoechogenicity with a rich color fow signal on sonography, and low-density lesions with a rimlike or slight enhancement in the arterial phase and hypoenhancement in the portal venous and late phases on CECT were the main imaging features for most nodular lesions.

The differential diagnosis of nodular PHL includes hepatocellular carcinoma, hemangioma and hepatic metastasis. Hepatocellular carcinoma is frequently associated with cirrhosis, an elevated level of serum AFP, and a rich color fow signal (even in small lesions), and CECTcommonly demonstrates a quick intense enhancement in the arterial phase and a hypo-enhancement in the portal venous and late phases. Hemangioma often displays hypoechoic lesions with peripheral thin hyperechoic capsules and no or little color fow signal, and CECT shows a characteristic peripheral nodular enhancement in the arterial phase and a slow centripetal progression in the portal venous and late phases. Hepatic metastasis in patients with a history of primary cancer often displays a “bulls-eye“ sign, with a thick rim-like enhancement in the arterial phase and a hypo-enhancement in the portal venous and late phases.[23]However, there are many overlapping features between nodular PHL and these hepatic tumors. There is no publication on specifc image for the diagnosis of nodular PHL. Although we could not fnd the specifc image, we indeed found that 7 patients with nodular type disease displayed patchy distribution with indistinct margin on US, which was an uncommon imaging appearance of hepatic tumors and might be the result of an invasive growth pattern of the tumor. Cholangiocarcinoma may give the same US appearance. Furthermore, cholangiocarcinoma on CECT mainly presents as an irregular peripheral rim-like or heterogeneous hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and a hypoenhancement in the portal venous and late phases, similar to the enhancement pattern of nodular PHL observed in our study. However, cholangiocarcinoma often displays no or little color fow signal and, moreover, peritumoral biliary dilation with calculus may be observed.[23]

In addition, in fve cases of nodular PHL, the CT images showed normal portal or hepatic vessels passing through the hepatic lesions, with no evidence of deviation or compression of these vessels. As PHL is derived from the liver mesenchyme, some inherent vessels running through the tumor may be evident during enhanced scanning and might present as normal vascular morphology. However, Apicella et al[24]also reported fve cases of liver malignancy, including hepatic lymphoma, metastatic melanoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma, in which either the portal or hepatic veins extended through a hepatic lesion without evidence of an appreciable mass effect, occlusion, or displacement of the vessels. Therefore, whether this represents a characteristic feature of PHL remains to be determined.

Because of the paucity of the disease, this series included only a small number of patients, a larger sample size is necessary for further assessment. Second, we did not perform a comparison between primary and secondary hepatic lymphoma, which might be an interesting study. Furthermore, FDG-PET/CT has been widely used in lymphoma imaging and only 2 patients were examined by this modality, we did not include FDG-PET/CT in our analysis. Previous studies[25,26]showed that FDG uptake varies among different studies and different histologic types. This would be an important consideration in further studies.

In conclusion, the infltration type of PHL is associated with histologic subtype. Although no pathognomonic imaging feature of PHL was identifed in this series, the diagnosis should be considered in the presence of the following signs: solitary or multiple liver lesions in the absence of defnite malignancy history, especially with patchy distribution, normal vessels extending through the lesion, and homogeneous or heterogeneous hepatomegaly associated with HBV positivity and an elevated level of serum LDH. Ultrasound-guided biopsy should be performed for a defnite diagnosis which might avoid unnecessary surgery and initiate early treatment.

Contributors:ZH proposed the study. LQ and WWP performed research and wrote the frst draft. JYJ and JZB collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. ZH is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution.

Competing interest:No benefts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Chambers TJ, O'Donoghue DP, Stansfeld AG. A case of primary lymphoma of the liver. J Clin Pathol 1976;29:967-970.

2 Lei KI, Chow JH, Johnson PJ. Aggressive primary hepatic lymphoma in Chinese patients. Presentation, pathologic features, and outcome. Cancer 1995;76:1336-1343.

3 Schweiger F, Shinder R, Rubin S. Primary lymphoma of the liver: a case report and review. Can J Gastroenterol 2000;14: 955-957.

4 Gazelle GS, Lee MJ, Hahn PF, Goldberg MA, Rafaat N, Mueller PR. US, CT, and MRI of primary and secondary liver lymphoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1994;18:412-415.

5 Rizzi EB, Schinina V, Cristofaro M, David V, Bibbolino C. Non-hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver in patients with AIDS: sonographic, CT, and MRI fndings. J Clin Ultrasound 2001;29:125-129.

6 Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma 1998;29:293-299.

7 Ozet A, Calişkaner Z, Deveci S, Ozet G, Celasun B, Arpaci F, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver (case report). Tumori 2000;86:492-494.

8 Page RD, Romaguera JE, Osborne B, Medeiros LJ, Rodriguez J, North L, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination chemotherapy. Cancer 2001;92:2023-2029.

9 Haider FS, Smith R, Khan S. Primary hepatic lymphoma presenting as fulminant hepatic failure with hyperferritinemia: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2008;2:279.

10 Wu SJ, Hung CC, Chen CH, Tien HF. Primary effusion lym-phoma in three patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Clin Virol 2009;44:81-83.

11 Gupta E, Rose JE, Straughen JE, Lamps LE, Olden KW. Hepatic failure and death due to new onset T cell lymphoma. J Gastrointest Cancer 2011;42:179-182.

12 Kang KM, Chung WC, Lee KM, Hur SE, Nah JM, Kim GH, et al. A case of primary hepatic lymphoma mimicking hepatitis. Korean J Hepatol 2005;11:284-288.

13 Wraight PG, Symmers C. Systemic pathology. New York: Elsevier; 1966:253.

14 Stancu M, Jones D, Vega F, Medeiros LJ. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma arising in the liver. Am J Clin Pathol 2002;118: 574-581.

15 Kim HS, Ko YH, Ree HJ. A case report of primary T-cell lymphoma of the liver. J Korean Med Sci 2000;15:240-242.

16 Leung VK, Lin SY, Loke TK, Chau TN, Leung CY, Fung TP, et al. Primary hepatic peripheral T-cell lymphoma in a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15: 288-290.

17 Harris AC, Kornstein MJ. Malignant lymphoma imitating hepatitis. Cancer 1993;71:2639-2646.

18 Andreola S, Audisio RA, Mazzaferro V, Doci R, Makowka L, Gennari L. Primary lymphoma of the liver showing immunohistochemical evidence of T-cell origin. Successful management by right trisegmentectomy. Dig Dis Sci 1988;33:1632-1636.

19 Sutton E, Malatjalian D, Hayne OA, Hanly JG. Liver lymphoma in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 1989;16:1584-1588.

20 Bowman SJ, Levison DA, Cotter FE, Kingsley GH. Primary T cell lymphoma of the liver in a patient with Felty's syndrome. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:157-160.

21 Anthony PP, Sarsfeld P, Clarke T. Primary lymphoma of the liver: clinical and pathological features of 10 patients. J Clin Pathol 1990;43:1007-1013.

22 Emile JF, Azoulay D, Gornet JM, Lopes G, Delvart V, Samuel D, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of the liver with nodular and diffuse infltration patterns have different prognoses. Ann Oncol 2001;12:1005-1010.

23 Hori M, Murakami T, Kim T, Tomoda K, Nakamura H. CT Scan and MRI in the Differentiation of Liver Tumors. Dig Dis 2004;22:39-55.

24 Apicella PL, Mirowitz SA, Weinreb JC. Extension of vessels through hepatic neoplasms: MR and CT fndings. Radiology 1994;191:135-136.

25 Elstrom R, Guan L, Baker G, Nakhoda K, Vergilio JA, Zhuang H, et al. Utility of FDG-PET scanning in lymphoma by WHO classifcation. Blood 2003;101:3875-3876.

26 Lin E, Lee M, Agoff N. FDG PET/CT diagnosis of hepatic lymphoma mimicking focal fatty infltration on CT. J Radiol Case Rep 2010;4:34-37.

Received October 24, 2013

Accepted after revision March 19, 2014

AuthorAffliations:Department of Ultrasound, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai Institute of Medical Imaging, Shanghai 200032, China (Lu Q, Zhang H, Wang WP, Jin YJ and Ji ZB)

Hui Zhang, MD, Department of Ultrasound, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai Institute of Medical Imaging, No. 180 Fenglin Road, Shanghai 200032, China (Tel: +86-21-64041990ext2474; Fax: +86-21-64220319; Email: zhang.hui@zs-hospital. sh.cn)

© 2015, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60285-X

Published online July 17, 2014.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Meetings and Courses

- Blunt abdominal injury with rupture of giant hepatic cavernous hemangioma and laceration of the spleen

- Enlarged pancreas: not always a cancer

- p38 MAPK inhibition alleviates experimental acute pancreatitis in mice

- Predictors of incidental gallbladder cancer in elderly patients

- Liver, biliary and pancreatic injuries in pancreaticobiliary maljunction model in cats