森林生态系统中植食性昆虫与寄主的互作机制、假说与证据

2014-08-11曾凡勇孙志强

曾凡勇,孙志强

(1. 中国林业科学研究院 科技管理处,北京 100091; 2. 国家林业局泡桐研究开发中心, 郑州 450003;3. 中国林科院经济林研究开发中心, 郑州 450003)

森林生态系统中植食性昆虫与寄主的互作机制、假说与证据

曾凡勇1,孙志强2,3,*

(1. 中国林业科学研究院 科技管理处,北京 100091; 2. 国家林业局泡桐研究开发中心, 郑州 450003;3. 中国林科院经济林研究开发中心, 郑州 450003)

围绕“多样性稳定性”假说、“联合抗性假说”、“生长势假说”、“胁迫假说”、以及下调、上调和推拉等机制与假说提出的背景与实验验证的证据,力图辨析其概念以及它们之间的相互关系。作者认为,多样性-稳定性机制关注森林生态系统的功能,是基于群落甚至景观层次。多样性条件下的联合抗性机制和联合易感性应属于稳定性中的抵抗力范畴。联合抗性机制的主要基础是基于资源集中假说和天敌假说,这些观点在种群层次上更易理解;上调力和下调力机制是以食物网底部的资源与顶端的天敌来探讨这种互作关系。因此,资源集中与上调力有着对应关系,而天敌假说只是下调力机制中的一个层面而已。植物生长势假说和植物胁迫假说力图从植物个体或种的群体的生长状态出发解析植食性动物的对寄主的选择趋势。上述有关植食性昆虫与寄主互作的机制、假说与证据是基于不同的层面提出的,因而在解析研究目标时,由于基本面的差异有可能会得出不同的结论。以近年来的研究进展和研究成果为依据有针对性地阐述这些理论对森林有害生物生态调控技术的指导作用,其中,联合抗性和联合易感性理论对指导森林有害生物生态控制具有更直接的指导作用。进一步提出了相应的亟待解决的科学问题。

植食性昆虫;寄主;互作机制;多样性稳定性假说;联合抗性假说

森林生态系统中主要的互作关系之一是植食性昆虫与其寄主间的关系,这种互作关系一直是森林生态系统及其功能研究的核心问题[1- 3],也是实施森林有害生物可持续控制的重要理论基础[4- 5]。针对这种互作关系,人们从不同的层面和视角提出了许多机制和假说,如以生物多样性理论为基础提出的“多样性稳定性”假说[6- 7]、围绕森林物种组成与结构提出的“联合抗性假说”[8- 9];以树木个体和群体为对象提出的“生长势假说”[10]、“胁迫假说”[11];以及以食物链为主导的下调、上调和推拉等相互制约机制[12- 16]。事实上, 这些理论和假说为解释森林生态系统自调控病虫灾害的机制提供了理论依据。

如何认识上述这些假说和机制,以及如何运用这些理论指导森林管理实践是森林生态学家和森林保护工作者的重要任务之一。本文针对人们提出的植食性昆虫与寄主间的互作关系的主要机制和假说,试图辨析其概念以及它们之间的相互关系,以近年来的研究进展和研究成果为证据辩证地剖析这些机制和假说对于森林有害生物生态调控的指导作用,并提出相应的亟待解决的科学问题。

1 多样性-稳定性机制的提出与验证

1.1 多样性-稳定性机制的提出

Elton[17]和Pimentel[18]首次描绘了在简单的生态系统(如人工纯林)中,病虫害的发生比在复杂生态系统中严重。随后有许多观察数据(而非实验数据)支持了森林生态系统的生物多样性是抑制和降低病虫害暴发的重要因素[18]。多样性-稳定性机制认为一个群体内物种多样性越丰富,其稳定性越高,亦即害虫及其天敌种群数量在时间序列上表现较低的波动幅度,从而避免了植食性昆虫种群数量的大规模暴发[7, 19]。最近通过数学方法证明,生物多样性和害虫间的相互作用能够影响系统稳定性[20]。因此,森林的生物多样性(如天然林)能够自调控病虫害暴发和降低病虫害的为害损失成为森林可持续经营的一个经典论据[21- 24]。

1.2 多样性-稳定性机制的验证

在农业和草地系统[25]中均观察到随着植物多样性增加,植食性为害减少,在森林生态系统中也有同样的发现[26- 27]。但有些作者观察到植物多样性的相反[28]或根本没有影响的结果[29],并指出植食性动物对植物具体种类的强烈的依赖性、而非植物多样性的调控作用[27, 30]。环境中存在植食性动物的寄主专化性,对植食性-植物多样性关系产生影响[24- 25]。其他节肢动物的研究显示,多样性-植食性关系是由群落水平的植物多样性调控[31]。

Vehviläinen[30]对芬兰6个寒带针叶林样地和1个温带针叶林样地开展了长期监测。监测的林分类型包括天然林、混交林及人工纯林,监测的主要内容是不同生物多样性条件下昆虫的发生情况,同时比较不同树龄、采样季节、以及不同试验设计(样地大小、密度)条件下昆虫种类、昆虫取食方式的差异及其对系统稳定性的影响。结果显示昆虫在取食方式和寄主的选择方面变化显著。取食方式上,不考虑寄主种类时,混交林和人工纯林中只有潜叶蛾(Phyllocnistisspp.)种群数量保持低密度且在时间序列上变化不大。但潜叶蛾在纯林中表现出更强的年度波动,验证了多样性-稳定性假说,即多样性丰富系统内的波动比简单系统小[32]。桦树(Betulaplatyphylla)混交林内的昆虫种群密度比纯林中的明显偏低,而栎树(Quercusaliena)和赤扬(Alnusglutinosa)混交林内的植食性昆虫数量比单一品种林(如栎树纯林)内更丰富。

Jactel和Brockerhoff[27]的结果表明,树种多样性的增加能有效减少林间昆虫数量。在由不同树种所组成的群落中,寡食性昆虫的数量明显较少,而杂食性昆虫数量存在一定的变化。他们认为天然林树种的组成比寄主树种丰富度更为重要。这个研究得出了一些重要结论,如(1)树种多样性抑制害虫爆发的积极效果随着相关树木种类比例增加而增加;(2)系统发生越远的树种组合越能表现对食叶害虫的抑制和调控的能力,如种子植物与裸子植物的混交;(3)系统发生相近的树种混交增加了杂食性害虫为害的可能。在天然林中,特定树种上寡食性昆虫数量的减少会导致相应的杂食性昆虫总体数量的增加[33]。因此,在一个特定的森林生态系统中,生产者的物种多样性可以减少消费者对生产者的依赖。

与之相反,有些研究却认为随着植物种类多样性增加、植食性昆虫种类和数量随之增加并增加了为害水平[29, 34- 36]。在中国亚热带森林开展的一项植食性昆虫与植物多样性关系的研究,分析了来自27个森林林分类型中的植食性昆虫的为害水平,目的是验证是否植物丰富度显著影响昆虫的种类与为害水平[36]。作者认为,作为植食性动物-植物多样性的正面关系是与资源集中假说相联系的,该假说认为随着植物种类多样性的增加使得寄主植物资源减少,从而导致寡食性动物为害水平的降低。该文证明在多样性丰富的亚热带森林系统,资源集中似乎不是总体植食性为害的主要决定因素。与传统的结论相比,杂食性昆虫对系统的影响更强,因为这些种类在高度多样性的植物群落中有着广泛的食物来源[36]。在亚热带森林中植物多样性与植食性动物的种类和为害间有着整体的正相关性。这与多数无论是森林系统还是草地系统的研究的结论相反,那些研究通常认为随着多样性增加植食性昆虫为害减少[25, 27, 37- 39]。

因此,研究者普遍认为特定环境中存在的植物种类以及植食性动物的寄主专化性,对植食性-植物多样性关系产生影响[24- 25]。同时,树种多样性对昆虫数量及其为害的影响在人工林、混交林和天然林中普遍依赖于昆虫取食方式和树种。但目前在群落水平上开展有关植物多样性调控害虫发生与为害的研究还很少见。

2 联合抗性假说(Associational resistance hypothesis)和联合易感性假说(Associational susceptibility hypothesis)的提出与验证

2.1 联合抗性假说的提出

Tahvanainen等提出,在特定森林生态系统中除寄主树木本身的抗性外,寄主树木与临近的其它物种整体上会表现出对植食性动物的“联合抗性”。因此,联合抗性常用来描述多样性丰富的植物群落中低水平的害虫为害[8, 40- 41]。支持联合抗性的主要假说包括天敌假说和资源集中假说[9]。

天敌假说认为天然林内丰富的、多样性的或有效的天敌群体控制植食性昆虫种群密度从而抑制其暴发;而资源集中假说试图预测植食性昆虫搜寻、发现和定居在寄主丰富的斑块的能力和趋向性,正如Root所强调的,“植食性昆虫更易发现并停留在寄主集中或近似于纯林林分中”[9]。大量的有关资源集中假说的研究来自于农业害虫,如对比在单一品种和低多样性水平的混交时害虫的群体行为[37, 42]。许多林分或小样地水平的研究支持该假说[9, 43- 45],Bach进一步在种群水平上发现昆虫多度的增加降低了集中种植的单一品种寄主的生长[46]。Long等在群落水平上对该假说展开了深入研究,发现寡食性甲虫(Trirhabdavirgata)降低了废弃耕地上其专化寄主秋麒麟(Solidagoaltissima)的生物量,并进而导致植物丰富度增加。该地区整体生物量的降低全部归功于由甲虫为害而造成的寄主生物量的降低,而这种植物是当地植物群落的优势种。他们的结果证实,当优势种密度增加,斑块中高密度寄主吸引了更多的甲虫[47]。

在另一项研究中,Knops等[48]观察到在不同多样性梯度水平下,寡食性昆虫种群对寄主植物资源集中度有两种截然不同的响应,而样地中植物丰富度对这种响应的影响较小。一方面,当寄主植物多度更高时,昆虫寄生的也高;另一方面,随着寄主植物密度增加,昆虫数量随之减少,Otway等将这种情况称之为资源稀释假说[35]。因此,该研究仅部分地支持资源集中假说。同样的,Knops 等[48],Koricheva等[49]和Haddad等[50]等的研究证实,至少对某些寡食性昆虫来说,其种群发生符合资源集中假说。但另一些研究同样展现了资源稀释发生的证据[42, 51- 52]。

2.2 联合易感性假说的提出

White和Whitham指出,当系统中主要害虫是杂食性昆虫,而首要寄主与次级寄主混交时,首要寄主会因资源的快速减少,导致害虫“溢出”到次级寄主上,使得这类天然林或混交林受杂食性昆虫为害比纯林内更为严重,这种现象被称为群体“联合易感性”[53- 54]。“联合易感性”普遍存在于森林中次级寄主上,尤其是当昆虫是杂食性且其食物来源具有等级性时(如同是阔叶树或同是针叶树),会导致昆虫种群呈现周期性的高密度的暴发[53, 55]

2.3 联合抗性假说和联合易感性假说的验证

Barbosa等提出[56],联合抗性和联合易感性的形成有非生物和生物机制两方面。非生物促进机制包括土壤条件、小气候影响等。土壤条件能影响关键植物周围的其他植物,并进一步改变了关键植物生长与抗性所需的土壤营养,如理论上,固氮植物近旁的其他植物最终会通过固氮植物组织的死亡和分解获得较丰富的氮源[57],类似的土壤变化可以通过植食性动物的取食,粪便的分解导致土壤营养成分的变化并促进关键植物近旁的植物生长或改变他们的抵抗力[58]。经由邻近植物的存在而形成的小气候会影响植食性动物的习性及其天敌。尽管鲜有研究揭示这些机制是否会导致联合抗性或联合易感性的形成,但小气候(如光强度、温度、湿度)的变化通过改变昆虫的产卵和寿命的确影响了其聚集及其对关键植物的取食;同时小气候通过影响天敌的搜寻、交配等行为,间接地影响植食性昆虫的数量和为害程度。以上的一条或全部的原因有可能决定了联合抗性/易感性形成的可能。

生物因素促进联合抗性/易感性形成是机制包括:

(1)相邻植物的特性直接改变取食关键植物昆虫的习性、存活及其天敌

目前,关于联合抗性或联合易感性的形成机制的研究还多停留在个体和种群水平上。如从植物的物理特征如色泽,各个器官的结构特点来判断促进或阻碍联合抗性机制或联合易感性的形成。在群落内,邻近植物可能通过简单的视觉阻隔效果或通过阻碍植食性动物的移动方向来降低关键植物被侵害的可能性[59- 60]。但邻居植物也可能作为吸引者而使植食性动物汇集在这些植物体上[8],进而减少了在关键植物的聚集和为害,即“推-拉”理论[61]。在人工管理的栖息地,采用这种推拉理论在农作物的害虫防治上取得了一定的效果[61- 62]。但也有例外,即由于邻居植物的吸引效果而使害虫“溢出”到关键植物上导致“联合易感性”的发生[53, 63]。另外,邻居植物对关键植物的影响很可能由化学信号和视觉效应调控。邻居植物上的取食者能产生挥发物从而影响邻近的关键植物抵抗和(或)受害的可能性。如邻近植物为天敌提供食物(如花粉,蜜等),直接促进天敌的聚集并进而间接地降低了取食者的密度,由此引发“联合抗性”发生[64]。反之,当邻近植物为关键植物提供互为补充的食物资源时,“联合易感性”随之发生。

联合作用广泛地存在于植物对植食性动物的相互作用关系中。但植食性动物间的相互作用有可能因被捕食者、病原或寄生天敌影响从而导致联合抗性/易感性的发生[65]。特定植食性动物引起的联合抗性/易感性的潜力与另一个概念有所区别,即天敌的不同响应机制能够调控(或成为作用机制导致)植物间联合抗性/易感性的发生[66]。Stenberg等发现植食性动物之间同样存在联合易感性的[67]。多年生草本植物绣线菊(Filipendulaulmaria)和紫珍珠菜(Lythrumsalicaria)影响着昆虫为害水平,因为膜翅目寄生天敌椰门托小蜂(Asecodesmento)同时寄生2种植物上各自专性甲虫。在绣线菊上的林奈球虫叶甲(Galerucellatenella)和紫珍珠菜上的紫珍珠菜甲虫(G.calmariensis)。林奈球虫叶甲的寄生率与绣线菊叶面积损失率呈负相关。混交的绣线菊和紫珍珠菜中共享的寄生天敌椰门托小蜂密度更高,因为绣线菊的花吸引的椰门托小蜂的量是紫珍珠菜的2倍。

Barbosa 和Caldas的研究结果尽管是间接证据,但仍表明联合易感性在协同发生的植食性动物间普遍发生[68]。有着相同特征的鳞翅目昆虫幼虫被同一类寄生天敌寄生的机会更多,显示了联合易感性的潜力。Shiojiri等[69]和Heimpel等[70]在相关研究中,强调了联合抗性/联合易感性的形成机制,虽然他们的研究并未直接针对联合抗性或联合易感性。他们指出,形成联合抗性/联合易感性的潜在影响机制,包括寄生性天敌在不同寄主上的聚集、这些寄生天敌卵的成活率,以及从一种或二种昆虫所取食寄主植物分泌物的差异如何影响寄生天敌对其寄主的搜寻。

(2)关键植物及其邻居植物的相对丰富度的差异直接或间接影响植食性动物的聚集[56]

通过一项连续2a对欧洲赤松(Pinussylvestris)纯林和与50%桦树(Betulapendula)混交林松树上的欧洲松叶蜂(Neodiprionsertifer(Hymenoptera,Diprionidae))数量、幼虫和卵的存活,捕食性天敌数量监测的结果显示:与纯林相比,混交林中松树上叶蜂的幼虫和卵的比例降低[71]。这与混交林中蚂蚁数量多有关。其他叶蜂天敌(如蜘蛛和捕食性半翅目昆虫)在不同地点有差异并与蚂蚁数量呈负相关,说明这些组分的相互作用。尽管混交林叶蜂存活低、提供了联合抗性的证据,相关研究表明这些树上有着比纯林更高的蚜虫群体,而这些蚜虫与蚂蚁放牧有关。因此,相比于考虑对单一植食性物种的联合抗性,将更大的系统如林分整体对普遍的植食性动物的联合抗性是更加实际的[71]。

笔者以昆嵛山天然赤松(Pinusdensiflora)林和寡食性食叶昆虫-昆嵛山腮扁叶蜂(Cephalciakunyushanica)为研究对象,对比树种组成类型、多样性、立地和林分因子对昆嵛山腮扁叶蜂种群密度的影响,研究结果以量化的方式证明在昆嵛山赤松自然保护区,树种组成对昆嵛山腮扁叶蜂种群的影响更为重要,赤松与其亲缘关系较近树种混交,昆虫种群稳定性较差,赤松与相邻树种形成对昆嵛山腮扁叶蜂联合易感作用,而与其它亲缘关系较远的树种混交,使害虫种群稳定性增强,进而形成联合抗性作用[72]。

在特定群落中,邻近植物的适口性(即被取食的程度)显著影响植食性昆虫的多度,以及被哺乳动物为害的程度,但不影响被昆虫取食所造成的为害程度。当周围植物不适口时,关键植物的植食性动物数量减少(即联合抗性);若周围植物同样适口时,关键植物和邻近植物的植食性动物数量没有差异[56]。但分类上差别较大的植物虽然能影响植食性动物多度,但不影响其所受到的为害程度。Barbosa等的研究结果表明,当以植食性动物多度作为因变量时,发现“联合抗性”多存在于植物分类地位较远的物种组合中(如不同的目之间);若邻近植物与关键植物属同一科、或属、或种时,对“联合抗性”的形成不会有任何影响。在人工栖息地(如农田),“联合抗性”和“联合易感性”能够通过斑块间相邻植物的运用或非作物植物的运用而形成。作者认为,在景观水平上,这种“联合抗性”和“联合易感性”也能够形成[56]。

3 植物胁迫假说(Plant stress hypothesis)和植物生长势假说(Plant vigor hypothesis) 的提出与验证

3.1 植物胁迫假说和植物生长势假说的提出

White提出“植物胁迫假说”,指出由于环境条件恶化改变了植物器官中生物化学物质合成以及叶部组织的化学成分,导致植物化学抗性物质降低,使得受胁迫的植物寄主更适合昆虫取食,因而这些植物体上的植食性昆虫种类和数量更多[73]。而在1991年,Price提出了“植物生长势假说”,他认为许多植食性昆虫更倾向于取食生长势旺盛的植物,由此与“植物胁迫假说”相对应[10]。 “植物生长势假说”适于揭示与植物生长过程有关的害虫发生情况;同时它还揭示了在某些情况下,尤其是在那些干旱的立地条件下,植物早期的抗性诱导的机制和后期抗性增强的机制。

3.2 植物胁迫假说和植物生长势假说的验证

“植物胁迫假说”在提出的早期得到了普遍认可,而且实验证据普遍支持受到中等胁迫的寄主由于其营养物质的增加而有利于植食性昆虫取食[74- 75],同时在一些树种、农作物中发现植食性昆虫危害与植物受胁迫强度成正相关[75- 76]。但后期的研究,如通过采用元分析(meta-analyses)开展受水胁迫的植物寄主对植食性昆虫发生影响的研究发现,受胁迫植物对刺吸式昆虫表现出显著的负效应,对咀嚼式式昆虫没有显著影响,同时,受胁迫的植物体上虫瘿密度减少[77- 78];而对其他一些昆虫,如天牛、潜叶蛾等的发生没有显著影响或这种影响具有不稳定性。整体上,Huberty和Denno的研究结果并不支持植食性昆虫在受水胁迫后的植物寄主体上呈现更高的丰富度和种群密度的假设[78]。

植物生长势,亦被称为“活力Vigor”,被定义为任何植物或植物模块的成长较平均生长速率更快,体积更大[79]。Price提出,与植物生长过程有关的昆虫更倾向于在长势旺盛的寄主体上产卵,以保障幼虫的发育[10];虽然Cobb等指出“植物生长势假说”并未证明任何机制来说明植食性昆虫更好地存活与植物活力(生长势)间的正相关关系,但他同时也承认一些可能的因素促使这种结果的发生,如资源的增加、食物质量的提高、和/或植物体内防御物质的减少,等[80]。“植物生长势假说”早期以虫瘿类昆虫为试验模板,目前该假说适于揭示更多不同取食方式的昆虫,如潜叶蝇、天牛、咀嚼式口器昆虫、刺吸式口器昆虫及卷叶蛾等[81- 82]。最近,Cornelissen等的研究结果进一步肯定了生长势旺盛的植物体更加并且显著地吸引植食性昆虫,但他们同时也强调植物活力对昆虫的存活并无显著影响。从取食方式看,对旺盛生长植物依赖性最强的昆虫是刺吸式口器昆虫、潜叶蝇和虫瘿类昆虫[83]。因此,作者同时指出,许多以植物活力为标准的品种选择应考虑其受危害的潜在风险[83]。

4 上调力和下调力的提出与验证

4.1 上调力和下调力的提出

天然林中病虫害另一个调节机制来自于食物链和食物网结构,即上调力“Bottom-Up forces”和下调力“Top-Down forces”机制[84]。Hairston等提出“绿色世界”假说,认为自然界中天敌制约着植食性动物的种群数量(即下调力),并使之保持在无法消耗完寄主资源的较低种群密度,使得自然界保持“绿色”[85]。上调力是指在每个营养水平均存在资源制约、即生产者制约机制,而下调力是捕食性制约机制。在特定生态系统的食物链上,生物体即可成为捕食者、也可成为食物资源制约者。White认为,除非植物处在环境胁迫下,植食性动物并不能明显地和显著地消耗其栖息地中所有植物资源,所有营养水平均由食物资源所制约[86]。

4.2 上调力和下调力的验证

上调力主要是通过植物本身的物理性状如蜡质层和保卫细胞[87- 88]、化学成分如毒素[89]以及信号挥发系统[90]、等,来抵抗昆虫的为害。植物的这些特点在空间上从植物个体的不同部位到不同植物种类之间存在显著变化[91- 92]。上调力的这种空间变化是其他营养级关系的主要基础。而下调力的影响主要表现在强度上。大多数学者认为寄生物、捕食者和病原有时会引起植食性昆虫的高死亡率,如有时寄生率非常高使得上调力几乎不发挥效果。但这种高寄生率或被捕食率在大地理尺度[93]和小的空间尺度的效果差异是明显的[94]。因此,这种立地条件的变化使得在某一地点量化的下调力不能适应于更大的系统或尺度。

尽管这些争论有时呈现极度的两级分化[95- 96],但目前绝大多数生态学家赞同无论是上调力还是下调力,均对调控植食性昆虫起到重要作用[94, 97]。关键是这些调控作用如何在时空序列中保持相对的平衡[97]。

有学者提出广泛的调控作用不但应包含上调力、下调力等纵向的作用力,还应包括水平方向的同一营养级内和不同营养级间的作用。水平作用力主要是指植食性昆虫种内和种间竞争[98]。尽管植食性动物间的竞争不能从本质上解释世界之“绿”,但它具有影响种特异性密度的效果[99]。因此,要了解影响虫口密度的各种因素及其强度,这种水平作用力必须加以考虑。

同时,上述任何力量的强弱会应立地条件的不同而不同,因而对于比较上调力相对下调力的研究常常迟滞于空间的变化[16]。从景观生态学的角度出发,由于景观是由不同栖息地的斑块所组成,许多调控力量、甚至大多数的调控力的强度会随着立地条件的变化而变化。同时,有学者提出与传统的上调力和下调力理论完全不同的一组影响力量,即非生物影响因素[16]。植食性昆虫种群密度受非生物因素影响的观点由来已久[100],非生物条件的影响程度随空间而变,例如小气候影响昆虫的存活、对资源的选择以及昆虫的分布[101- 102]。非生物条件影响的效果往往通过营养关系,如通过影响寄主植物的质量[103]或相互作用物种的种群动态[104]等而受到调控。因此,无论其作用效果是直接或是间接,由非生物因子引起的不同空间的植食性昆虫死亡率的差异应当包含在影响当中。

5 结语

森林生态系统所具有的结构复杂性、时空稳定性和对病虫灾害较高的耐害性与自我补偿能力等特点,是实现病虫害可持续控制的基础条件;而森林生态系统自调控病虫害的能力,不但与森林生态系统植物群落的结构和树种组成特征有关,也与天然林中物种多样性较高有关[105]。纵观上述这些植食性昆虫与植物寄主互作的假说或机制,它们是基于不同的层面或尺度提出的,因而在解析研究目标时,由于基本面的差异有可能会得出不同的结论。深入辨析这些植食性昆虫与植物寄主互作的假说或机制的适用方位可以看到,它们之间存在着辩证统一的关系。

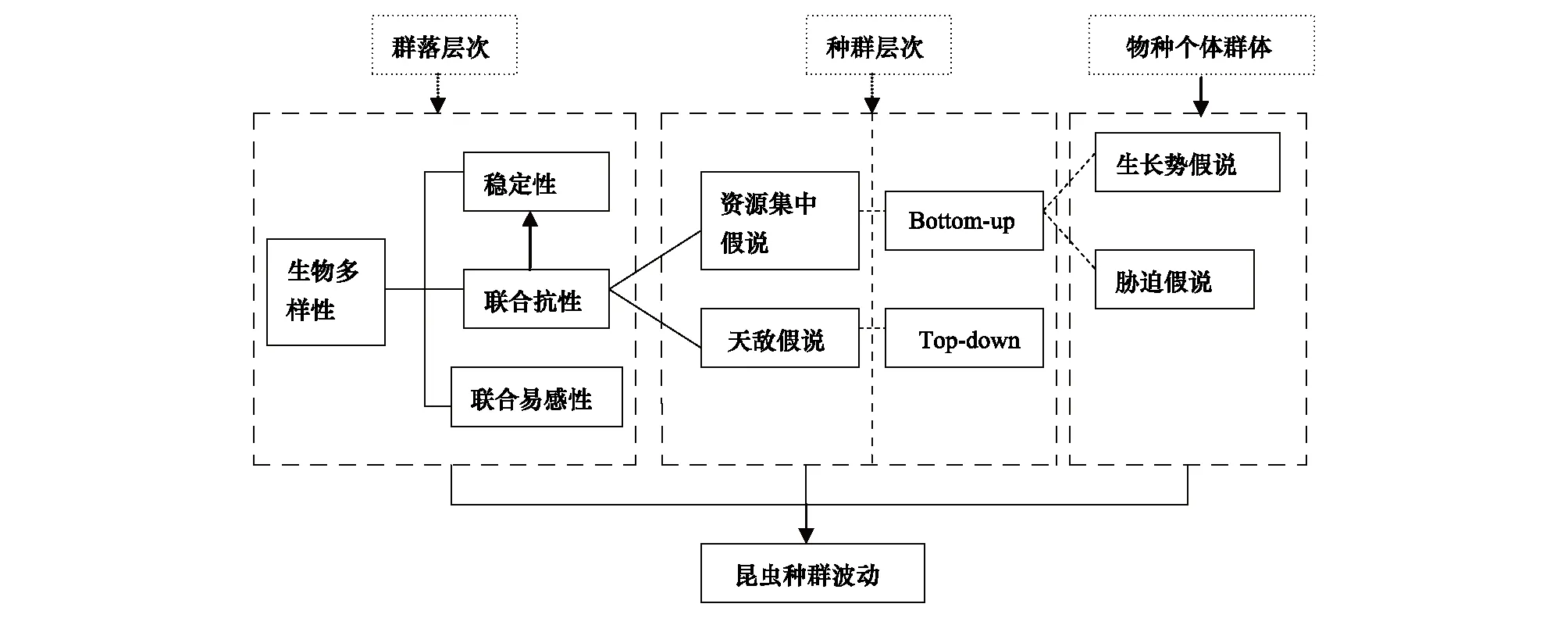

多样性-稳定性机制关注森林生态系统的功能,是基于群落甚至景观层次。森林病虫害干扰所涉及的稳定性概念主要是指森林生态系统遭受生物干扰后系统的抵抗力和恢复力。如同其他的相互作用,如消费者-资源相互关系、竞争、共生等,联合抗性和联合易感性通常包含了两种有机体之间的相互作用,以及这种相互作用的结果如何影响第3个物种(植食性动物)或被植食性动物影响。因此,多样性条件下的联合抗性机制和联合易感性应属于稳定性中的抵抗力范畴。联合抗性机制的主要基础是基于资源集中假说和天敌假说,这些观点在种群层次上更易理解;而基于食物链和食物网结构提出的即上调力和下调力机制,以生态系统食物网底部的资源与顶端的天敌来探讨其中的相互作用关系。因此,资源集中与上调力有着对应关系,但各自的出发点不同,资源集中重在探讨植食性昆虫可利用的资源总量、而下调力更侧重于这种食物链的营养关系;类似的,天敌假说只是下调力机制中的一个层面而已(图1)[106]。植物生长势假说和植物胁迫假说力图从植物个体的状态出发解析植食性动物的选择趋势,实际上,更多地是探讨资源的属性问题。因而,可以从其个体或种的群体的角度进行研究。其中,植物胁迫假说更多地与植物所处的栖息地环境有关。

图1 天然林调控病虫害机制与假说关系图[106]Fig.1 Relations among mechanism and hypothesis of natural forest mediating pests[106]

其中,联合抗性和联合易感性理论对指导森林有害生物生态控制具有更直接的指导作用。但这些理论仍然需要进一步完善。有研究初步揭示,森林生态系统中关键植物和邻居植物的相对多度对在景观水平上形成“联合抗性”或“联合易感性”显得重要[56]。景观水平的“联合易感性”的形成很大程度上依赖于主要植食性动物的食物资源是否分布在周围的栖息地中,或周围的栖息地的条件是否能促进植食性动物的越冬存活率[107]。邻近栖息地也可能成为景观中动物扩散的障碍,从而创造出景观水平的联合抗性[108]。但这类研究还很不系统,尚未形成对森林经营和管理具有指导意义的理论;同时,“联合抗性”和“联合易感性”的强度、稳定性以及对植物适应性的影响也可能随着时间变化、环境条件的改变以及植食性动物和植物的多度的变化而变化[56]。长期的种群和群落水平的“联合抗性”和“联合易感性”的效应的研究很少,这可能是未来需要努力的方向,而这些研究对指导森林的经营管理具有现实的指导意义。

我国森林病虫害的防控技术体系尽管经过了50年的不断完善,提出了适合中国国情的防治策略和方法,但是,可持续控制病虫灾害的核心技术问题仍未取得突破性进展,根本原因在于森林食叶害虫与寄主互作机制研究一直未能取得突破[109- 110]。森林保护学必须与生态学紧密结合,只有深刻了解森林有害生物对森林组成、结构的相互影响的过程,才能真正实现森林植食性昆虫的可持续控制。

致谢: 澳大利亚CSIRO王应平博士对本文写作提供帮助。

[1] Hooper D U, Chapin Iii F S, Ewel J J, Hector A, Inchausti P, Lavorel S, Lawton J H, Lodge D M, Loreau M, Naeem S, Schmid B, Setälä H, Symstad A J, Vandermeer J, Wardle D A. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecological Monographs, 2005, 75(1): 3- 35.

[2] Balvanera P, Pfisterer A B, Buchmann N, He J S, Nakashizuka T, Raffaelli D, Schmid B. Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services. Ecology Letters, 2006, 9(10): 1146- 1156.

[3] Hector A, Bagchi R. Biodiversity and ecosystem multifunctionality. Nature, 2007, 448(7150): 188- 190.

[4] Cardinale B J, Srivastava D S, Duffy J E, Wright J P, Downing A L, Sankaran M, Jouseau C. Effects of biodiversity on the functioning of trophic groups and ecosystems. Nature, 2006, 443(7114): 989- 992.

[5] Bailey J K, Wooley S C, Lindroth R L, Whitham T G. Importance of species interactions to community heritability: a genetic basis to trophic-level interactions. Ecology Letters, 2006, 9(1): 78- 85.

[6] Elton C S. The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958.

[7] Goodman D. The theory of diversity-stability relationships in ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 1975, 50(3): 237- 266.

[8] Tahvanainen J O, Root R B. The influence of vegetational diversity on the population ecology of a specialized herbivore,Phyllotretacruciferae(Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Oecologia, 1972, 10(4): 321- 346.

[9] Root R B. Organization of a plant-arthropod association in simple and diverse habitats: the fauna of collards (Brassicaoleracea). Ecological Monographs, 1973, 43(1): 95- 124.

[10] Price P W. The plant vigor hypothesis and herbivore attack. Oikos, 1991, 62(2): 244- 251.

[11] Joern A, Mole S. The plant stress hypothesis and variable responses by blue grama grass (Boutelouagracilis) to water, mineral nitrogen, and insect herbivory. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2005, 31(9): 2069- 2090.

[12] Kitching R L. Food webs in phytotelmata: Bottom-Up” and Top-Down” explanations for community structure. Annual Review of Entomology, 2001, 46(1): 729- 760.

[13] Terborgh J, Lopez L, Nunez P, Rao M, Shahabuddin G, Orihuela G, Riveros M, Ascanio R, Adler G H, Lambert T D. Ecological meltdown in predator-free forest fragments. Science, 2001, 294(5548): 1923- 1926.

[14] Walker M, Jones T H. Relative roles of top-down and bottom-up forces in terrestrial tritrophic plant-insect herbivore-natural enemy systems. Oikos, 2001, 93(2): 177- 187.

[15] Prokopy R J. Two decades of bottom-up, ecologically based pest management in a small commercial apple orchard in Massachusetts. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 2003, 94(3): 299- 309.

[16] Gripenberg S, Roslin T. Up or down in space? Uniting the bottom-up versus top-down paradigm and spatial ecology. Oikos, 2007, 116(2): 181- 188.

[17] Elton C S. The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

[18] Pimentel D. Species diversity and insect population outbreaks. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 1961, 54(1): 76- 86.

[19] McCann K S. The diversity-stability debate. Nature, 2000, 405(6783): 228- 233.

[20] Thébault E, Loreau M. Trophic interactions and the relationship between species diversity and ecosystem stability. The American Naturalist, 2005, 166(4): 95- 114.

[21] Larsen J B. Ecological stability of forests and sustainable silviculture. Forest Ecology and Management, 1995, 73(1/3): 85- 96.

[22] Bengtsson J, Nilsson S G, Franc A, Menozzi P. Biodiversity, disturbances, ecosystem function and management of European forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 2000, 132(1): 39- 50.

[23] Hartley M J. Rationale and methods for conserving biodiversity in plantation forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 2002, 155(1/3): 81- 95.

[24] Koricheva J, Vehviläinen H, Riihimäki J, Ruohomäki K, Kaitaniemi P, Ranta H. Diversification of tree stands as a means to manage pests and diseases in boreal forests: myth or reality? Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 2006, 36(2): 324- 336.

[25] Unsicker S B, Baer N, Kahmen A, Wagner M, Buchmann N, Weisser W W. Invertebrate herbivory along a gradient of plant species diversity in extensively managed grasslands. Oecologia, 2006, 150(2): 233- 246.

[26] Jactel H, Brockerhoff E, Duelli P. A test of the biodiversity-stability theory: meta-analysis of tree species diversity effects on insect pest infestations, and re-examination of responsible factors // Scherer-Lorenzen M, Körner C, Schulze E D, eds. Forest Diversity and Function Temperate and Boreal Systems Ecological Studies. Berlin: Springer, 2005, 176: 235- 262.

[27] Jactel H, Brockerhoff E G. Tree diversity reduces herbivory by forest insects. Ecology Letters, 2007, 10(9): 835- 848.

[28] Vehviläinen H, Koricheva J, Ruohomäki K, Johansson T, Valkonen S. Effects of tree stand species composition on insect herbivory of silver birch in boreal forests. Basic and Applied Ecology, 2006, 7(1): 1- 11.

[29] Scherber C, Mwangi P N, Temperton V M, Roscher C, Schumacher J, Schmid B, Weisser W W. Effects of plant diversity on invertebrate herbivory in experimental grassland. Oecologia, 2006, 147(3): 489- 500.

[30] Vehviläinen H, Koricheva J, Ruohomäki K. Tree species diversity influences herbivore abundance and damage: meta-analysis of long-term forest experiments. Oecologia, 2007, 152(2): 287- 298.

[31] Hanley M E. Seedling herbivory and the influence of plant species richness in seedling neighbourhoods. Plant Ecology, 2004, 170(1): 35- 41.

[32] MacArthur R. Fluctuations of animal populations and a measure of community stability. Ecology, 1955, 36(3): 533- 536.

[33] Barone J A. Host-specificity of folivorous insects in a moist tropical forest. Journal of Animal Ecology, 1998, 67(3): 400- 409.

[34] Koricheva M, Huss-Danell, Joshi H. Insects affect relationships between plant species richness and ecosystem processes. Ecology Letters, 1999, 2(4): 237- 246.

[35] Otway S J, Hector A, Lawton J H. Resource dilution effects on specialist insect herbivores in a grassland biodiversity experiment. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2005, 74(2): 234- 240.

[36] Schuldt A, Baruffol M, B hnke M, Bruelheide H, H rdtle W, Lang A C, Nadrowski K, Von Oheimb G, Voigt W, Zhou H Z, Assmann T. Tree diversity promotes insect herbivory in subtropical forests of south-east China. Journal of Ecology, 2010, 98(4): 917- 926.

[37] Andow D A. Vegetational diversity and arthropod population response. Annual Review of Entomology, 1991, 36(1): 561- 586.

[38] Hambäck P A, Beckerman A P. Herbivory and plant resource competition: a review of two interacting interactions. Oikos, 2003, 101(1): 26- 37.

[39] Sobek S, Scherber C, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T. Sapling herbivory, invertebrate herbivores and predators across a natural tree diversity gradient in Germany′s largest connected deciduous forest. Oecologia, 2009, 160(2): 279- 288.

[40] Karban R. Associational resistance for mule′s ears with sagebrush neighbors. Plant Ecology, 2007, 191(2): 295- 303.

[41] Sholes O D V. Effects of associational resistance and host density on woodland insect herbivores. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2008, 77(1): 16- 23.

[42] Rhainds M, English-Loeb G. Testing the resource concentration hypothesis with tarnished plant bug on strawberry: density of hosts and patch size influence the interaction between abundance of nymphs and incidence of damage. Ecological Entomology, 2003, 28(3): 348- 358.

[43] Zhang Q H. Olfactory Recognition and Behavioural Avoidance of Angiosperm Non-Host Volatiles by Conifer Bark Beetles [D]. Alnarp, Sweden: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 2001.

[44] Zhang Q H, Schlyter F. Olfactory recognition and behavioural avoidance of angiosperm nonhost volatiles by conifer-inhabiting bark beetles. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 2004, 6(1): 1- 20.

[45] Baier P, Führer E, Kirisits T, Rosner S. Defence reactions of Norway spruce against bark beetles and the associated fungusCeratocystispolonicain secondary pure and mixed species stands. Forest Ecology and Management, 2002, 159(1/2): 73- 86.

[46] Bach C E. Effects of plant density and diversity on the population dynamics of a specialist herbivore, the striped cucumber beetle,Acalymmavittata(Fab). Ecology, 1980, 61(6): 1515- 1530.

[47] Long Z T, Mohler C L, Carson W P. Extending the resource concentration hypothesis to plant communities: effects of litter and herbivores. Ecology, 2003, 84(3): 652- 665.

[48] Knops J M H, Tilman D, Haddad N M, Naeem S, Mitchell C E, Haarstad J, Ritchie M E, Howe K M, Reich P B, Siemann E, Groth J. Effects of plant species richness on invasion dynamics, disease outbreaks, insect abundances and diversity. Ecology Letters, 1999, 2(5): 286- 293.

[49] Koricheva J, Mulder C P H, Schmid B, Joshi J, Huss-Danell K. Numerical responses of different trophic groups of invertebrates to manipulations of plant diversity in grasslands. Oecologia, 2000, 125(2): 271- 282.

[50] Haddad NM, Tilman D, Haarstad J, Ritchie M, Knops J M H. Contrasting effects of plant richness and composition on insect communities: a field experiment. The American Naturalist, 2001, 158(1): 17- 35.

[51] Yamamura K. Biodiversity and stability of herbivore populations: influences of the spatial sparseness of food plants. Population Ecology, 2002, 44(1): 33- 40.

[52] Kareiva P. Influence of vegetation texture on herbivore populations: resource concentration and herbivore movement // Denno R F, McClure M S, eds. Variable Plants and Herbivores in Natural and Managed Systems. New York: Academic Press, 1983: 259- 289.

[53] White J A, Whitham T G. Associational susceptibility of cottonwood to a box elder herbivore. Ecology, 2000, 81(7): 1795- 1803.

[54] Brown B J, Ewel J J. Herbivory in complex and simple tropical successional ecosystems. Ecology, 1987, 68(1): 108- 116.

[55] Futuyma D J, Wasserman S S. Resource concentration and herbivory in oak forests. Science, 1980, 210(4472): 920- 922.

[56] Barbosa P, Hines J, Kaplan I, Martinson H, Szczepaniec A, Szendrei Z. Associational resistance and associational susceptibility: having right or wrong neighbors. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2009, 40(1): 1- 20.

[57] van Ruijven J, Berendse F. Diversity-productivity relationships: initial effects, long-term patterns, and underlying mechanisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005, 102(3): 695- 700.

[58] Frost C J, Hunter M D. Recycling of nitrogen in herbivore feces: plant recovery, herbivore assimilation, soil retention, and leaching losses. Oecologia, 2007, 151(1): 42- 53.

[59] Coll M, Bottrell D G. Effects of nonhost plant on an insect herbivore in diverse habitats. Ecology, 1994, 75(3): 723- 731.

[60] Holmes D M, Barrett G W. Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica) dispersal behavior in intercropped vs. monoculture soybean agroecosystems. American Midland Naturalist, 1997, 137(2): 312- 319.

[61] Cook S M, Khan Z R, Pickett J A. The use of push-pull strategies in integrated pest management. Annual Review of Entomology, 2006, 52(1): 375- 400.

[62] Tillman P. Sorghum as a trap crop forNezaraviridulaL. (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) in cotton in the southern United States. Environmental Entomology, 2006, 35(3): 771- 783.

[63] Wada N, Murakami M, Yoshida K. Effects of herbivore-bearing adult trees of the oakQuercuscrispulaon the survival of their seedlings. Ecological Research, 2000, 15(2): 219- 227.

[64] Harmon J, Ives A, Losey J, Olson A, Rauwald K.Coleomegillamaculata(Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) predation on pea aphids promoted by proximity to dandelions. Oecologia, 2000, 125(4): 543- 548.

[65] Redman A M, Scriber J M. Competition between the gypsy moth,Lymantriadispar, and the northern tiger swallowtail,Papiliocanadensis: interactions mediated by host plant chemistry, pathogens, and parasitoids. Oecologia, 2000, 125(2): 218- 228.

[66] Stiling P, Rossi A M, Cattell M V. Associational resistance mediated by natural enemies. Ecological Entomology, 2003, 28(5): 587- 592.

[67] Stenberg J A, Heijari J, Holopainen J K, Ericson L. Presence of Lythrum salicaria enhances the bodyguard effects of the parasitoidAsecodesmentoforFilipendulaulmaria. Oikos, 2007, 116(3): 482- 490.

[68] Barbosa P, Caldas A. Seasonal patterns of parasitism and differential susceptibility among species in macrolepidopteran assemblages onSalixnigra(Marsh) andAcernegundoL. Ecological Entomology, 2007, 32(2): 181- 187.

[69] Shiojiri K, Takabayashi J, Yano S, Takafuji A. Infochemically mediated tritrophic interaction webs on cabbage plants. Population Ecology, 2001, 43(1): 23- 29.

[70] Heimpel G E, Neuhauser C, Hoogendoorn M. Effects of parasitoid fecundity and host resistance on indirect interactions among hosts sharing a parasitoid. Ecology Letters, 2003, 6(6): 556- 566.

[71] Kaitaniemi P, Riihimäki J, Koricheva J, Vehviläinen H. Experimental evidence for associational resistance against the European pine sawfly in mixed tree stands. Silva Fennica, 2007, 41(2): 259- 268.

[72] Zhu Y P, Sun Z Q, Zhang X Y, Liang J, Jiang M Y, Wu X M. Tree species composition determines associational resistance or associational susceptibility: a caseCephalciakunyushanica. Journal of Chinese Ecology, 2013, 32(4): 938- 945.

[73] White, TCR. The abundance of invertebrate herbivores in relation to the availability of nitrogen in stress food plants. Oecologia, 1984, 63(1): 90- 105.

[74] McClure M S. Foliar nitrogen: a basis for host suitability for elongate hemlock scale,Fioriniaexterna(Homoptera: Diaspididae). Ecology, 1980, 61(1): 72- 79.

[75] Mattson W J, Haack R A. The role of drought in outbreaks of plant-eating insects. BioScience, 1987, 37(2): 110- 118.

[76] Heinrichs E. Plant Stress-Insect Interactions. New York: John Wiley and Sons Ltd., 1988.

[77] Koricheva J, Larsson S, Haukioja E. Insect performance on experimentally stressed woody plants: a meta-analysis. Annual Review of Entomology, 1998, 43(1): 195- 216.

[78] Huberty A F, Denno R F. Plant water stress and its consequences for herbivorous insects: a new synthesis. Ecology, 2004, 85(5): 1383- 1398.

[79] Gonçalves-Alvim S J, Faria M L, Fernandes G W. Relationships between four neotropical species of galling insects and shoot vigor. Anais da Sociedade Entomológica do Brasil, 1999, 28(1): 147- 155.

[80] Cobb N S, Mopper S, Gehring C A, Caouette M, Christensen K M, Whitham T G. Increased moth herbivory associated with environmental stress of pinyon pine at local and regional levels. Oecologia, 1997, 109(3): 389- 397.

[81] Cunningham S A, Floyd R B.Toonaciliatathat suffer frequent height-reducing herbivore damage by a shoot-boring moth (Hypsipylarobusta) are taller. Forest Ecology and Management, 2006, 225(1): 400- 403.

[82] Ide J Y. Inter-and intra-shoot distributions of the ramie moth caterpillar,Arctecoerulea(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in ramie shrubs. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 2006, 41(1): 49- 55.

[83] Cornelissen T, Wilson Fernandes G, Vasconcellos-Neto J. Size does matter: variation in herbivory between and within plants and the plant vigor hypothesis. Oikos, 2008, 117(8): 1121- 1130.

[84] Power M E. Top-down and bottom-up forces in food webs: do plants have primacy. Ecology, 1992, 73(3): 733- 746.

[85] Hairston N G, Smith F E, Slobodkin L B. Community structure, population control, and competition. American Naturalist, 1960, 94(879): 421- 425.

[86] White T C R. Weather, food and plagues of locusts. Oecologia, 1976, 22(2): 119- 134.

[87] Dai X H, Zhu C D, Xu J S, Liu R L, Wang X X. Effects of physical leaf features of host plants on leaf-mining insects. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2011, 31(5): 1440- 1449.

[88] Brennan E B, Weinbaum S A. Stylet penetration and survival of three psyllid species on adult leaves and ‘waxy’ and ‘de-waxed’ juvenile leaves ofEucalyptusglobulus. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 2001, 100(3): 355- 363.

[89] Cornell H V, Hawkins B A. Herbivore responses to plant secondary compounds: a test of phytochemical coevolution theory. The American Naturalist, 2003, 161(4): 507- 522.

[90] Colazza S, Fucarino A, Peri E, Salerno G, Conti E, Bin F. Insect oviposition induces volatile emission in herbaceous plants that attracts egg parasitoids. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2004, 207(1): 47- 53.

[91] Roslin T, Gripenberg S, Salminen J P, Karonen M, O′Hara R B, Pihlaja K, Pulkkinen P. Seeing the trees for the leaves-oaks as mosaics for a host-specific moth. Oikos, 2006, 113(1): 106- 120.

[92] Castells E, Berhow M A, Vaughn S F, Berenbaum M R. Geographic variation in alkaloid production inConiummaculatumpopulations experiencing differential herbivory byAgonopterixalstroemeriana. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 2005, 31(8): 1693- 1709.

[93] Brewer A M, Gaston K J. The geographical range structure of the holly leaf-miner. II. Demographic rates. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2003, 72(1): 82- 93.

[94] Denno R F, Gratton C, Peterson M A, Langellotto G A, Finke D L, Huberty A F. Bottom-up forces mediate natural-enemy impact in a phytophagous insect community. Ecology, 2002, 83(5): 1443- 1458.

[95] Murdoch W W. "Community Structure, Population Control, and Competition"-a critique. The American Naturalist, 1966, 100(912): 219- 226.

[96] Lawton J H, McNeill S. Between the devil and the deep blue sea: on the problem of being a herbivore // Anderson R M, Turner B D, Taylor L R. Population Dynamics. Symposium of the British Ecological Society, 1979: 223- 244.

[97] Denno RF, Lewis D, Gratton C. Spatial variation in the relative strength of top-down and bottom-up forces: causes and consequences for phytophagous insect populations. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 2005, 42(4): 295- 311.

[98] Ferrenberg S M, Denno R F. Competition as a factor underlying the abundance of an uncommon phytophagous insect, the salt-marsh planthopperDelphacodespenedetecta. Ecological Entomology, 2003, 28(1): 58- 66.

[99] Roslin T, Roland J. Competitive effects of the forest tent caterpillar on the gallers and leaf-miners of trembling aspen. Ecoscience, 2005, 12(2): 172- 182.

[100] DeBach P. The role of weather and entomophagous species in the natural control of insect populations. Journal of Economic Entomology, 1958, 51(4): 474- 484.

[101] Irwin J T, Lee R E Jr. Cold winter microenvironments conserve energy and improve overwintering survival and potential fecundity of the goldenrod gall fly,Eurostasolidaginis. Oikos, 2003, 100(1): 71- 78.

[102] Roy D B, Thomas J A. Seasonal variation in the niche, habitat availability and population fluctuations of a bivoltine thermophilous insect near its range margin. Oecologia, 2003, 134(3): 439- 444.

[103] Henriksson J, Haukioja E, Ossipov V, Ossipova S, Sillanp S, Kapari L, Pihlaja K. Effects of host shading on consumption and growth of the geometridEpirritaautumnata: interactive roles of water, primary and secondary compounds. Oikos, 2003, 103(1): 3- 16.

[104] Tuda M, Matsumoto T, Itioka T, Ishida N, Takanashi M, Ashihara W, Kohyama M, Takagi M. Climatic and intertrophic effects detected in 10-year population dynamics of biological control of the arrowhead scale by two parasitoids in southwestern Japan. Population Ecology, 2006, 48(1): 59- 70.

[105] Vacher C, Bourguet D, Rousset F, Chevillon C, Hochberg M E. Modelling the spatial configuration of refuges for a sustainable control of pests: a case study ofBtcotton. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 2003, 16(3): 378- 387.

[106] Sun Z Q. The Impact of Stand Types and Site Conditions on Population Dynamic of Kunyushan Web-Spinning Sawfly (Cephalciakunyushanica) [D]. Beijing: Chinese Academy of Forestry, 2011.

[107] Botero-Garcés N, Isaacs R. Influence of uncultivated habitats and native host plants on cluster infestation by grape berry moth,EndopizaviteanaClemens (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), in Michigan vineyards. Environmental Entomology, 2004, 33(2): 310- 319.

[108] Bhar R, Fahrig L. Local vs. landscape effects of woody field borders as barriers to crop pest movement. Conservation Ecology, 1998, 2(2): 3- 3.

[109] Sun Z Q, Wen R J, Fu J M. Feasibility of population ecological management of forest foliage insect pest in China. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2001, 20(2): 77- 80.

[110] Liang J, Zhang X Y. Forest pest ecological control. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2005, 41(4): 168- 176.

参考文献:

[72] 朱彦鹏, 孙志强, 张星耀, 梁军, 姜明媛, 吴晓明. 树种组成决定联合抗性或易感性: 以昆嵛山腮扁叶蜂发生为例. 生态学杂志, 2013, 32(4): 938- 945.

[87] 戴小华, 朱朝东, 徐家生, 刘仁林, 王学雄. 寄主植物叶片物理性状对潜叶昆虫的影响. 生态学报, 2011, 31(5): 1440- 1449.

[106] 孙志强. 林分类型和立地条件对昆嵛山腮扁叶蜂种群动态的影响 [D]. 北京: 中国林业科学研究院, 2011.

[109] 孙志强, 文瑞君, 傅建敏. 我国森林食叶害虫种群生态控制可行性分析. 生态学杂志, 2001, 20(2): 77- 80.

[110] 梁军, 张星耀. 森林有害生物生态控制. 林业科学, 2005, 41(4): 168- 176.

Mechanism, hypothesis and evidence of herbivorous insect-host interactions in forest ecosystem

ZENG Fanyong1,SUN Zhiqiang2,3,*

1ScienceandTechnologyManagementOffice,ChineseAcademyofForestry,Beijing100091,China2PaulowniaR&DCenterofChina,ChineseAcademyofForestry,Zhengzhou450003,China3Non-timberForestryR&DCenter,ChineseAcademyofForestry,Zhengzhou450003,China

This paper analyzed the concepts, different mechanisms of herbivorous insect-host interactions and hypotheses based on their academic origins and recent experimental evidence. The theories we analyzed include diversity-stability mechanism, associational resistance hypothesis, associational susceptibility hypothesis, plant vigor hypothesis, plant stress hypothesis, bottom-up forces, top-down forces, and push-pull mechanism, etc. Diversity-stability mechanism focuses on functioning of forest ecosystem that is developed using evidence collected at community and landscape scale. Associational resistance and associational susceptibility is a resistance type of diversity-stability. The foundation for associational resistance hypothesis was built based on resource concentration hypothesis and natural enemy hypothesis. The resource concentration hypothesis predicted that herbivores were more likely to be found in patches where their host plants were abundant. The enemy hypothesis can explain why herbivores are fewer in forest ecosystems with a more abundant and diverse community of natural enemies. This was consistent with the diversity-stability hypothesis, which predicts that a community becomes more stable with higher diversity. These theories were easily understandable at population scale. Bottom-up forces and Top-down forces discuss the interaction between herbivorous insects and host plants along the food chains, in which bottom-up refers to restriction mechanism caused by resources on the bottom of food web while Top-down refers to natural enemies on the top of food chain. Therefore, there was a corresponding relationship between resources concentration hypothesis and bottom-up forces, and enemy hypothesis corresponds to top-down forces. Plant vigor hypothesis and plant stress hypothesis predict that herbivores tend to select host plants based on their growth conditions population size. The above herbivore-host interaction theories are proposed based on different levels in a forest ecosystem, which might result in different conclusion due to the differences in ecosystem levels. This paper then elaborated the guiding roles of these theories on forest pest control based on recent progresses. Among these theories, Associational resistance and associational susceptibility may be applicable to guide forest management, specifically forest pest control. The evidence suggested that associational resistance and associational susceptibility interactions may be mediated by biotic and abiotic mechanisms. However, there were few studies on how habitats, the spatial and temporal availability of resources determine landscape-level impacts of associational resistance and associational susceptibility, and how the strength, consistency, and relative impact of associational resistance and associational susceptibility on plant fitness vary temporally and spatially as environmental conditions, herbivore and plant abundance change. These are the questions urgently needed to be answered in this field.

herbivorous insect; host; insect-host interaction mechanism; diversity-stability mechanism; associational resistance hypothesis

国家林业公益性行业科研专项项目(201304406);国家“十二五”科技支撑计划项目(2012BAD19B0801)资助

2013- 04- 27;

2013- 09- 22

10.5846/stxb201304270830

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: sun371@ 163.com

曾凡勇,孙志强.森林生态系统中植食性昆虫与寄主的互作机制、假说与证据.生态学报,2014,34(5):1061- 1071.

Zeng F Y,Sun Z Q.Mechanism, hypothesis and evidence of herbivorous insect-host interactions in forest ecosystem.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2014,34(5):1061- 1071.