In Situ IR Spectroscopic Study on the Hydrogenation of 1,3-Butadiene on Fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3Catalyst

2014-07-31ZhangJingWuWeichengLiuShiyang

Zhang Jing; Wu Weicheng; Liu Shiyang

(1. Liaoning Shihua University, College of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Environmental Engineering, Fushun 113001; 2. SINOPEC Tianjin Branch, Tianjin 300270)

In Situ IR Spectroscopic Study on the Hydrogenation of 1,3-Butadiene on Fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3Catalyst

Zhang Jing1; Wu Weicheng1; Liu Shiyang2

(1. Liaoning Shihua University, College of Chemistry, Chemical Engineering and Environmental Engineering, Fushun 113001; 2. SINOPEC Tianjin Branch, Tianjin 300270)

The surface species formed from the adsorption of 1,3-butadiene and 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation over the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst was studied by in situ IR spectroscopy. It is found that 1,3-butadiene adsorption on the Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst mainly forms π-adsorbed butadiene (πsand πd) and σ-bonded surface species. These species are adsorbed mainly on the surface Moδ+(0<δ<2) sites as evidenced by co-adsorption of 1,3-butadiene and CO on the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst. The IR spectrometric analysis show that hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst produces mainly butane coupled with a small portion of butene. The selectivity of butene during the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst might be explained by the adsorption mode of adsorbed 1,3-butadiene. Additionally, the active sites of the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst may be covered by coke during the hydrogenation reaction of 1,3-butadiene. The treatment with hydrogen at 673 K cannot remove the coke deposits from the surface of the Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst.

fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst; hydrogenation; 1,3-butadiene; in situ IR spectroscopy

1 Introduction

In recent years, early transition metal carbides are of interest because they have many superior properties such as high melting point, good thermal and catalytic behavior, and excellent electronic characteristics[1-3]. More importantly, the early transition metal carbides have shown interesting catalytic properties in many hydrogen-involved reactions, such as hydrodesulfurization (HDS)[4-8], hydrodenitrogenation (HDN)[9-10], hydrogenolysis ofn-butane[11], conversion of methane[12], dehydrogenation of propane[13], etc. Nevertheless, the hydrogenation of unsaturated hydrocarbons over the transition metal carbide has not yet been fully explored.

Molybdenum carbide (Mo2C), which is easily prepared with high surface area using the temperature programmed reaction, is especially of interest among a large group of transition metal carbide catalysts[14-15]. It has been shown that the Mo2C surface is very active. The freshly prepared Mo2C is rapidly oxidized when it is exposed to air, so it must be passivated using a mixture containing 1% of O2in helium gas to avoid violent oxidation[16]. As a result, the studies on the carbides catalyst are usually focused on passivated or reduced carbides. Our previous study[16]has shown that the passivation of Mo2C with oxygen dramatically changed the catalyst both in its surface structure and catalytic activity, i.e., the surface of the passivated Mo2C is different from that of the fresh Mo2C catalyst. Therefore, it is of significance to gain an insight into the activity and nature of fresh Mo2C catalysts for hydrogenation reactions, especially for the hydrogenation of unsaturated hydrocarbons.

In situ IR spectroscopy is a predominant technique used in the surface characterization of supported catalysts[17-18]. In our previous work, the surface active sites of the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3[16], Mo2N/γ-Al2O3[19], and the fresh Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3for hydrogenation of benzene[20]have been studied by in situ IR spectroscopy. In this paper, hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst was studied using in situ IR spectroscopy. We attempt to investigate the surface adsorbed species of 1,3-butadiene and the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst in order to gain an insight into the structure-performance relationship for 1,3-butadiene hy-drogenation over fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis of fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst

Ammonium heptamolybdate of the analytical reagent grade was used without further purification. The support γ-Al2O3(SBET=108 m2/g) was provided by Degussa. A fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst was prepared by temperature programmed reaction (TPR) of MoO3/γ-Al2O3as reported in our previous work[16].

2.2 IR spectroscopic characterization

The detailed information about the in-situ IR cell can be found in our previous work[16]. The IR spectroscopic experiments were carried out under the following conditions: (1) The cell was evacuated to 1.3×10-3Pa, prior to being exposed to a mixture of CO (with a partial pressure of 1.3×103Pa) and 1,3-butadiene (with a partial pressure of 1.3×103Pa) for co-adsorption. (2) The cell was exposed to a mixture of 1,3-butadiene (with a partial pressure of 1.3×103Pa) and H2(with a partial pressure of 1.3×104Pa) at different temperatures. (3) The fresh Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3catalyst was treated by a mixture of 1,3-butadiene/ H2(1.3×103/1.3×104Pa) at 773 K for 30 min, then was subjected to adsorption by CO. The deactivated Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst was regenerated by hydrogen treatment at 673 K for 120 min, and then was subjected to adsorption by CO. All IR spectra were collected at room temperature on a Nicolet Impect 410 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm-1and 64 scans in the region of 4 000 cm-1—1 000 cm-1.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Co-adsorption of 1,3-butadiene and CO on fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst

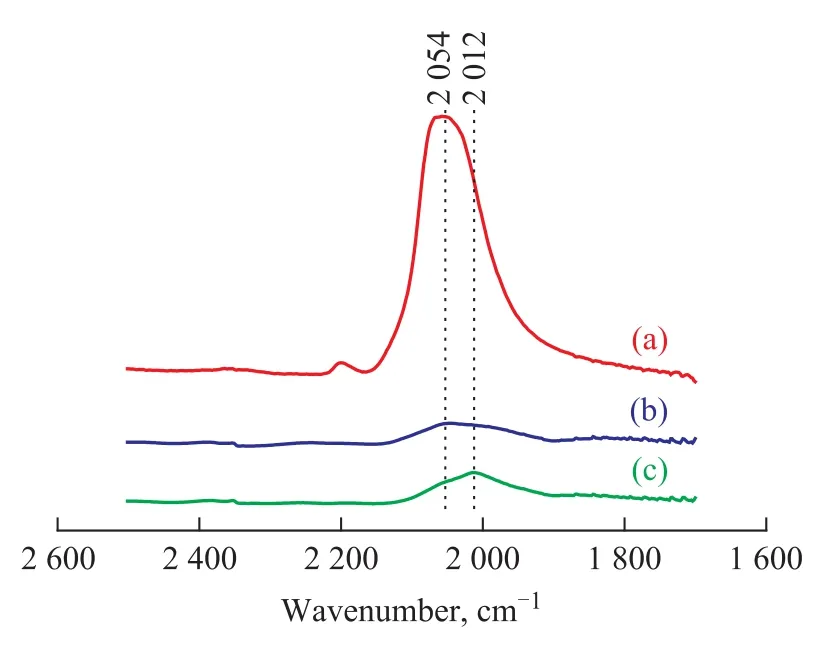

Figure 1 shows the IR spectra of CO co-adsorbed with 1,3-butadiene on the Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst at room temperature. Figure 1a displays the spectra of CO adsorbed on fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst. It is shown that CO species adsorbed on a fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3sample gave two characterized IR bands at 2054 cm-1and 2196 cm-1(Figure 1a). The band at 2054 cm-1could be assigned to the linearly adsorbed CO on Moδ+(0<δ<2) sites of fresh Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3sample, while the band at 2196 cm-1might be assigned to a CCO species that were formed from the reaction of CO with the surface-active carbon atoms of Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3[16]. Figure 1b shows the IR spectroscopic analysis of 1,3-butadiene species which were pre-adsorbed on the Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst prior to the introduction of CO. In comparison with the results of Figure 1a, the band at 2196 cm-1disappeared, while the band at 2 054 cm-1decreased significantly in intensity in Figure 1b. In addition, a weak band at 2 012 cm-1was observed in Figure 1b. This result implies that the pre-adsorbed 1,3-butadiene prevented CO from its adsorption on Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst surface. The IR spectrum of CO that was pre-adsorbed on Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3catalyst prior to the introduction of 1,3-butadiene is shown in Figure 1c. It can be seen that Figure 1b is similar to Figure 1c. Moreover, the band intensity of 2012 cm-1in Figure 1c is stronger than that in Figure 1b. It is obvious that the presence of pre-adsorbed 1,3-butadiene strongly suppress the adsorption of CO on the Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3sample, especially at the Moδ+(0<δ<2) sites. Moreover, the pre-adsorbed 1,3-butadiene has a significant influence on the frequency of CO vibration. These results indicate that 1,3-butadiene is adsorbed mainly at the Moδ+(0<δ<2) sites of the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst and have both electronic and blocking effects on the surface sites. The bathochromic shift of υ(CO) caused by coadsorption of 1,3-butadiene can be interpreted in terms of the electronic effects of π-donation of 1,3-butadiene.

Figure 1 IR spectra of CO adsorbed at RT on Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst

3.2 Hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene on fresh Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3catalyst

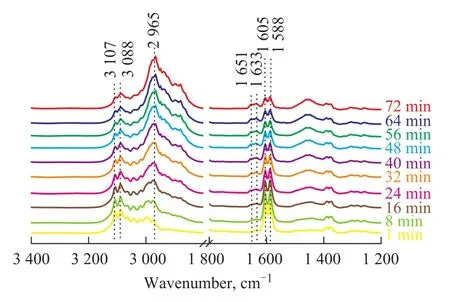

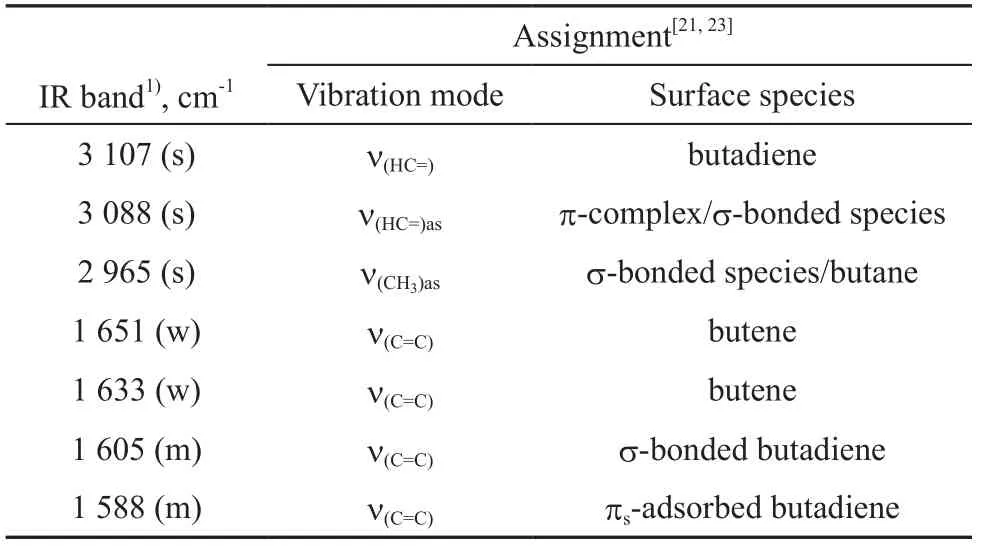

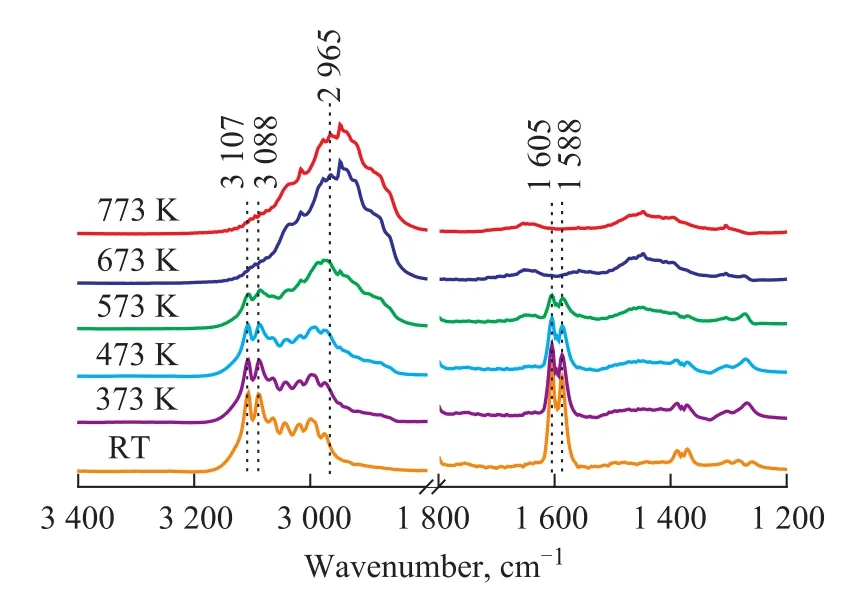

Figure 2 shows the IR spectra of 1,3-butadiene/hydrogen (1.3×103/1.3×104Pa) mixture adsorbed on fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst at RT at different adsorption time. Four bands at 3 107 cm-1, 3 088 cm-1, 1 605 cm-1and 1 588 cm-1are observed when the adsorption time is 1 min. The bands at 3 088 cm-1and 3 107 cm-1appear due to the stretching mode of unsaturated C—H groups and can be ascribed to the π-adsorbed species[21]. The bands at 1 605 cm-1and 1 588 cm-1can be ascribed to the stretching mode of C=C bonds. According to Sheppard’s results[22], υ(C=C) is observed in the region of 1 650—1 550 cm-1for C=C groups with only σ-type metal substitution, while υ(C=C) is observed in the region of 1 650 cm-1—1 550 cm-1for C=C groups with π-bonding only. So the band at 1 605 cm-1could be attributed to σ-bonded species and the band at 1 588 cm-1to single π-adsorbed 1,3-butadiene (πs). It is found out that the characteristic bands of 1,3-butadiene (at 3 107 cm-1, 3 088 cm-1(υ(=CH)), 1 605 cm-1, and 1 588 cm-1(υ(C=C))) show a declining intensity, while the characteristic bands of alkane at 2 965 cm-1(υ(CH3)) and 1 445 cm-1(δ(CH3)) appear with an increasing adsorption time. These two bands (at 2 965 cm-1and 1 445 cm-1) are assigned to the gas-phase butane. After the adsorption time is increased to 1 h, the bands ascribed to 1,3-butadiene decrease greatly, while the characteristic bands of butane are clearly observed. These results show that 1,3-butadiene can be easily hydrogenated to form butane over the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst. However, two additional bands at 1 651 cm-1and 1 633 cm-1in the υ(C=C)region are observed in Figure 2. These two IR bands in the υ(C=C)region are the same as those of 1-butene, indicating that 1-butene may be an intermediate of the reaction for converting 1,3-butadiene to butane. A tentative assignment for the IR bands[21,23]is given in Table 1.

Figure 2 IR spectra of 1,3-butadiene/H2(1.3×103/1.3×104Pa) adsorbed on fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst at RT with an increasing adsorption time

Table 1 Assignment of the IR bands of 1,3-butadiene adsorbed on fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst

As it has been discussed above, our IR results show that hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over the fresh Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3catalyst produces mainly butane along with a small portion of butene. The possible reason why fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst shows a certain butene selectivity during the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene can be inferred as follows: Adsorption of 1,3-butadiene on the Mo2C/ γ-Al2O3catalyst results in both π- and σ-bonded species. According to the sum frequency generation (SFG) studies described by Somorjai[24-25], the π-adsorbed species are considered to be the dominant intermediate for the olefin hydrogenation reaction, while the σ-bonded species may play a role in side reactions and/or in catalyst deactivation. For 1,3-butadiene adsorption, both πsand πdadsorbed species are formed on the surface of Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst, while only πs-adsorbed species are formed during butene adsorption as evidenced by Wu’s results[21]. It is found out that the heat of adsorption of πd-adsorbed 1,3-butadiene is about twice that of πs-adsorbed butene[26]. Thus, the butene formed by hydrogenation is less readily adsorbed on the catalyst and cannot easily replace the adsorbed 1,3-butadiene. Therefore, butene is desorbed from the surface of the catalyst and enters into the gas phase after it is formed by the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene. This is the reason why a small portion of butene is ob-served from the IR spectroscopic analysis.

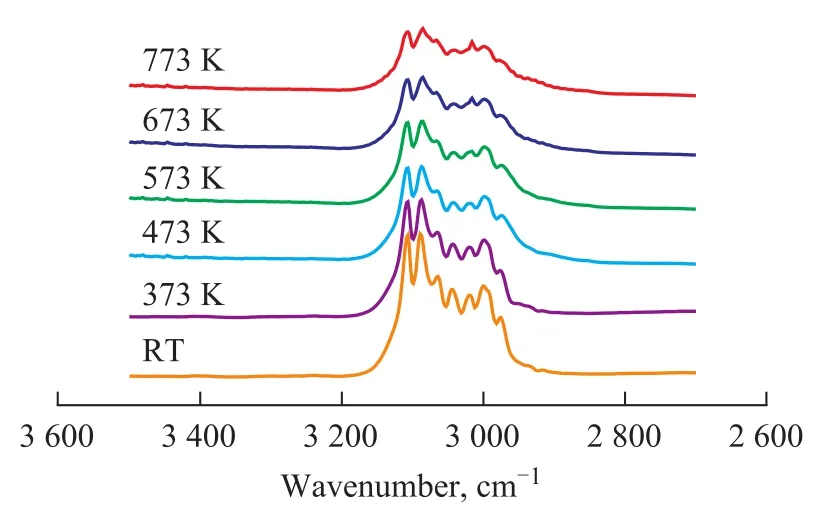

Figure 3 IR spectra of 1,3-butadiene/H2(1.3×103/1.3×104Pa) mixture adsorbed on Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst at different temperatures

Figure 4 IR spectra of 1,3-butadiene/H2(1.3×103/1.3×104Pa) mixture adsorbed onγ-Al2O3at different temperatures

3.3 Effect of reaction temperature on the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene

The effect of the reaction temperature on the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst was also investigated, and the results are displayed in Figure 3. Figure 3 shows the changes of IR bands of 1,3-butadiene adsorbed on Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst at high temperature. It is observed that the characteristic bands of 1,3-butadiene decrease in intensity, while the butane related bands increase in intensity with an increasing temperature. The IR band at 3 170 cm-1, 3 088 cm-1, 1 605 cm-1,and 1 588 cm-1, which is the characteristic feature of1,3-butadiene, disappears at 673 K, while an IR band at 2 965 cm-1assigned to butane is observed. It can be seen that the changes of IR bands at high temperature are similar to that of bands at RT. Moreover, the high temperature improves the hydrogenation reaction of 1,3-butadiene to form butane. Figure 4 gives the IR spectra of 1,3-butadiene/H2(1.3×103/1.3×104Pa) mixture adsorbed on γ-Al2O3support at different temperatures. The adsorbed 1,3-butadiene on γ-Al2O3support gives IR bands similar to that of 1,3-butadiene in the gas phase, indicating that the 1,3-butadiene is weakly or physically absorbed on the γ-Al2O3support. Moreover, the spectra in Figure 4 do not show obvious change with an increasing temperature. These results suggest that the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst exhibits a high activity for the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene.

3.4 The changes of reaction active sites of Mo2C/γ-Al2O3before and after butadiene hydrogenation

Figure 5 IR spectra of CO adsorbed at RT on Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst before and after 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation reaction

Figure 5 compares the IR spectra of CO adsorbed on Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst before and after 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation reaction. As mentioned before, CO species adsorbed on a fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3sample gave two characterized IR bands at 2 054 cm-1and 2 196 cm-1, respectively. However, these two adsorption bands disappeared after 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation reaction. These two characteristic bands were still not observed even after the catalyst was reduced by H2at 673 K. This result may suggest that the coke deposited on the Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst is formed during the hydrogenation reaction of 1,3-butadiene. The treatment of catalyst with hydrogen at 673 K cannot remove the coke deposits from the surface of Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst. As a result, CO cannot be adsorbed on Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst, and the adsorptionbands of CO are not observed.

4 Conclusions

Hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene on fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst was studied by in situ IR spectroscopy, and the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Adsorption of 1,3-butadiene on the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst mainly forms π-adsorbed butadiene (πsand πd) and σ-bonded species. These species are adsorbed mainly on the surface Moδ+(0<δ<2) sites.

(2) The selectivity in butene during the hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene over the fresh Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst may be explained by competitive adsorption between 1,3-butadiene and butane. The πd-adsorbed 1,3-butadiene inhibits the adsorption of butene, and then butene is desorbed from the surface of the catalyst and enters into the gas phase after it is formed.

(3) Coke deposited on the Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst may be formed during the hydrogenation reaction of 1,3-butadiene. The treatment of catalyst with hydrogen at 673 K cannot remove the coke deposits from the surface of the Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst.

Acknowledgements:This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 20903054), Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2014020107), Program for Liaoning excellent talents in university (No. LJQ2014041), and is also sponsored by the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry (SRF for ROCS, SEM).

[1] Yu C C, Ramanathan S, Dhandapani B, et al. Bimetallic Nb-Mo carbide hydroprocessing catalysts: Synthesis, characterization, and activity studies[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 1997, 101(4): 512-518

[2] Niu S Q, Hall M B. Theoretical studies on reactions of transition metal complexes[J]. Chemical Review, 2000, 100(2): 353-406

[3] Rohmer M M, Benard M, Poblet J M. Structure, reactivity, and growth pathways of metallocarbohedrenes M8C12 and transition metal/carbon clusters and nanocrystals: A challenge to computational chemistry[J]. Chemical Review, 2000, 100(2): 495-542

[4] Aegerter P A, Quigley W W C, Simpson G J, et al. Thiophene hydrodesulfurization over alumina-supported molybdenum carbide and nitride catalysts: Adsorption sites, catalytic activities, and nature of the active surface[J]. Journal of Catalysis, 1996, 164(1):109-121

[5] Li S, Lee J S. Molybdenum nitride and carbide prepared from heteropolyacid: III. Hydrodesulfurization of benzothiophene[J]. Journal of Catalysis, 1998, 178(1): 119-136

[6] Costa P Da, Potvin C, Manoli J M, et al. New catalysts for deep hydrotreatment of diesel fuel: Kinetics of 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene hydrodesulfurization over aluminasupported molybdenum carbide[J]. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemistry, 2002, 184(1/2): 323-333

[7] McCrea K R, Logan J W, Tarbuck T L, et al. Thiophene hydrodesulfurization over alumina-supported molybdenum carbide and nitride catalysts: Effect of Mo loading and phase[J]. Journal of Catalysis, 1997, 171(1): 255-267

[8] Diaz B, Sawhill S J, Bale D H, et al. Hydrodesulfurization over supported monometallic, bimetallic and promoted carbide and nitride catalysts[J]. Catalysis Today, 2003, 86(1/4): 191-209

[9] Al-Megren H A, González-Cortés S L, Xiao T C, et al. A comparative study of the catalytic performance of Co-Mo and Co(Ni)-W carbide catalysts in the hydrodenitrogenation (HDN) reaction of pyridine[J]. Applied Catalysis A: General, 2007, 329: 36-45

[10] Sayag C, Suppan S, Trawczyński J, et al. Effect of support activation on the kinetics of indole hydrodenitrogenation over mesoporous carbon black composites-supported molybdenum carbide[J]. Fuel Processing Technology, 2002, 77/78: 261-267

[11] Lee J S, Locatelli S, Oyama S T, et al. Molybdenum carbide catalysts: 3. Turnover rates for the hydrogenolysis ofn-butane[J]. Journal of Catalysis, 1990, 125(1): 157-170

[12] York A P E, Claridge J B, Brungs A J, et al. Molybdenum and tungsten carbides as catalysts for the conversion of methane to synthesis gas using stoichiometric feedstocks[J]. Chemical Communications, 1997, 100(1): 39-40

[13] Solymosi F, Németh R, Óvári L, et al. Reactions of propane on supported Mo2C catalysts[J]. Journal of Catalysis, 2000, 195(2): 316-325.

[14] Solymosi F, Szoke A, Cserenyi J. Conversion of methane to benzene over Mo2C and Mo2C/ZSM-5 catalysts[J]. Catalysis Letters, 1996, 39(3/4): 157-161

[15] Wang L B, Li Q W, Mei T, et al. A thermal reduction route to nanocrystalline transition metal carbides from waste polytetrafluoroethylene and metal oxides[J]. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2012, 137(1): 1-4

[16] Wu W C, Wu Z L, Liang C H, et al. In situ FT-IR spectroscopic studies of CO adsorption on fresh Mo2C/Al2O3catalyst[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2003, 107(29): 7088-7094

[17] Shen Q, Fan Y J, Yin L, et al. Two-dimensional continuous online in situ ATR-FTIR spectroscopic investigation of adsorption of butyl xanthate on CuO surfaces[J]. Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica, 2014, 30(2): 359-364 (in Chinese)

[18] Christensen A N. The crystal growth of molybdenum carbide, Mo2C, by a floating zone technique[J]. Journal of Crystal Growth, 1976, 33(1): 58-60

[19] Yang S, Li C, Xu J, et al. Surface sites of alumina-supported molybdenum nitride characterized by FTIR, TPDMS, and volumetric chemisorption[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry, 1998, 102(36): 6986-6993

[20] Yang F, Zhang J, Wu W C. Hydrogenation of benzene over Mo2C/γ-Al2O3catalyst studied by in situ IR spectroscopy[J]. Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica, 2014, 30(5):943-949 (in Chinese)

[21] Wu Z L, Hao Z X, Ying P L, et al. An IR study on selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene on transition metal nitrides: 1,3-Butadiene and 1-butene adsorption on Mo2N/ γ-Al2O3catalyst[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2000, 104(51): 12275-12281

[22] Sheppard N, Cruz C D L. Vibrational spectra of hydrocarbons adsorbed on metals: Part I. Introductory principles, ethylene, and the higher acyclic alkenes[J]. Advances in Catalysis, 1996, 41: 1-112

[23] Wu Z L, Hao Z X, Li C, et al. Selective hydrogenation of 1,3-butadiene on molybdenum nitride catalyst: Identification of the adsorbed hydrocarbonaceous species[J]. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis, 2001, 138: 445-452

[24] Somorjai G A, Rupprechter G. Molecular studies of catalytic reactions on crystal surfaces at high pressures and high temperatures by infrared-visible sum frequency generation (SFG) surface vibrational spectroscopy[J]. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 1999, 103(10): 1623-1638

[25] Cremer P, Su X, Shen Y R, et al. Ethylene hydrogenation on Pt (111) monitored in situ at high pressures using sum frequency generation[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1996, 118(12): 2942-2949

[26] Tourillon G, Cassuto A, Jugnet Y, et al. Buta-1,3-diene and but-1-ene chemisorption on Pt (111), Pd (111), Pd (110) and Pd50Cu50(111) as studied by UPS, NEXAFS and HREELS in relation to catalysis[J]. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions, 1996, 92(23): 4835-4841

Received date: 2014-04-09; Accepted date: 2014-08-05.

Wu Weicheng, E-mail: weichengwu@ live.cn.

杂志排行

中国炼油与石油化工的其它文章

- Comparative Studies on Low Noise Greases Operating under High Temperature Oxidation Conditions

- A Method for Crude Oil Selection and Blending Optimization Based on Improved Cuckoo Search Algorithm

- Experimental Research on Pore Structure and Gas Adsorption Characteristic of Deformed Coal

- Mathematical Model of Natural Gas Desulfurization Based on Membrane Absorption

- Ni2P-MoS2/γ-Al2O3Catalyst for Deep Hydrodesulfurization via the Hydrogenation Reaction Pathway

- Effects of Airflow Field on Droplets Diameter inside the Corrugated Packing of a Rotating Packed Bed