Ni2P-MoS2/γ-Al2O3Catalyst for Deep Hydrodesulfurization via the Hydrogenation Reaction Pathway

2014-07-31LiuLihuaLiuShuqun

Liu Lihua; Liu Shuqun

(School of Chemistry and Materials Science, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, Anhui 235000)

Ni2P-MoS2/γ-Al2O3Catalyst for Deep Hydrodesulfurization via the Hydrogenation Reaction Pathway

Liu Lihua; Liu Shuqun

(School of Chemistry and Materials Science, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, Anhui 235000)

A series of highly active Ni2P-MoS2/γ-Al2O3catalysts were prepared and characterized, the catalytic performance of which was evaluated through hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene. The result indicated that when the amount of Ni2P was 4%, the catalyst showed a relatively high activity to provide a reliable reference for the hydrodesulfurization pathway in comparison with the conventional NiMo and NiMoP catalysts. The physicochemical properties of the catalysts were correlated with their catalytic activity and selectivity on hydrodesulfurization. The stacking number of active MoS2phases was important for influencing the hydrogenation activity.

MoS2catalysts; nickel phosphide; morphology; hydrodesulfurization

1 Introduction

The removal of sulfur compounds from crude oils has received much attention in recent years because of more stringent environmental regulations. It is well known that the key for achieving deep hydrodesulfurization (HDS) of diesel fuel is the elimination of most refractory polyaromatic sulfur compounds such as dibenzothiophenes (DBT) with alkyl groups in positions 4 and 6[1-3]. These molecules cannot be transformed into corresponding desulfurized products via direct desulfurization route (DDS) because the alkyl groups adjacent to the sulfur atom hinder the σ bonding perpendicular to the catalyst surface needed for the C—S bond hydrogenolysis. Therefore, the HDS of refractory DBT compounds occurs predominantly through the hydrogenation (HYD) pathway, in which the reactant molecule is first hydrogenated to intermediates and then the C—S bond is broken to remove the sulfur atoms. Hence, the hydrogenating functionality of the catalyst is of great significance and determines its activity for deep HDS[4].

It is well known that the outstanding hydrogenating capacity of noble metals makes them potential catalysts for deep HDS. Geantet and co-workers[5]examined a catalytic system based on the addition of a low content of Pt to commercial NiMo, CoMo, or NiW catalysts supported on alumina. It was found out that a 20%—40% increase in the activity could be achieved. This behavior was ascribed to the key interactions between Pt and “NiWS” or“CoMoS” phases. But the platinum element is too expensive to implement many catalytic reactions. The transition metal phosphides (TMPs) show catalytic performance similar to those of platinum-group metals in a variety of reactions involving hydrogenation. Upon considering the immediate economic benefits, it is necessary to use TMPs as replacements for noble metal catalysts. TMPs have the additional advantages of high thermal stability, mechanical durability, and greater tolerance to common catalyst poisons. Therefore, it is highly desirable to develop a less expensive but efficient catalyst to replace precious-metal catalysts.

Transition metal phosphides have been recently attracting attention not only because they are very active, but also because they are much more stable than metal carbides or nitrides in terms of their reaction on hydrogen sulfide[6]. The temperature-programmed reduction (TPR) method is proved to be an effective and conventional way to prepare phosphides. This method has the disadvantage which requires a high temperature for metal phosphide preparation, resulting in large catalyst particles and relatively low catalytic activity. Nickel phosphide was synthesizedvia the decomposition of hypophosphite precursors[7-8]. Ni2P/γ-Al2O3exhibits good activity for hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene.

In the present work, we explored into the possibility of enhancing the hydrogenation ability of the conventional MoS2catalysts by the addition of Ni2P. A series of the Ni2P-modified MoS2(NPMS) catalysts supported on alumina were prepared, characterized, and the catalytic activity in the HDS of DBT was evaluated. The principal objective was to clarify the relation between the hydrogenation performance and the promoter of Ni2P.

2 Experimental

2.1 Catalyst preparation

Ammonium tetrathiomolybdate ((NH4)2MoS4) was prepared following the route published in the literature[9]. The Ni2P-modified MoS2/γ-Al2O3catalysts were prepared via two steps. In the first step, the MoS2active phase supported on γ-Al2O3(SBET=265.9 m2/g,VP=0.65 cm3/g) was prepared by the wetness impregnation method with (NH4)2MoS4solution, and then the solid material was dried and decomposed under N2flow at 400 ℃ for 3 h to generate MoS2/γ-Al2O3catalyst. In the second step, the as-prepared catalyst was incipiently impregnated with an aqueous solution of Ni(H2PO2)2·6H2O, followed by drying at 60 ℃ and calcination at 300 ℃ under N2. It was denoted as NPMS-xcatalyst, in whichxwas the mass fraction of Ni2P. The Mo content of the NPMS catalysts was 18.0% as determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis.

The reference catalysts were prepared by the incipient wetness impregnation of the MoS2/γ-Al2O3catalyst with aqueous solution of Ni(NO3)2and a mixed solution of Ni(NO3)2and NH4H2PO4, respectively. They were denoted as NMS-xand NMP-x, in whichxwas the mass fraction of NiO. The Mo content of the reference catalysts was 18.0% as determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis.

2.2 Catalyst characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were recorded on a JEM-2100UHR analytical microscope operated at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Samples for TEM analyses were prepared by making the sample well dispersed in ethanol and putting a drop of the solution on a carbon-coated copper grid, and the solution was allowed to evaporate leaving behind the sample on the carbon grid.

The N2adsorption-desorption analysis was performed at -196 ℃ using an automated gas adsorption analyzer (Tristar 3020, Micromeritics) with the samples being outgassed at 140 ℃ for 6 h under vacuum prior to measurements. The surface areas were calculated by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller method, and the pore size distributions were determined by the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda method from desorption.

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis was carried out by a PANalytical’s X’Pert PRO diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation operated at a tube voltage of 45 kV and a tube current of 40 mA. The scan rate was 8(°)/min and the scan range of 2θwas from 5° to 85°.

Temperature-programmed reduction of the catalysts in the presence of hydrogen (H2-TPR) was carried out on a Quantachrome CHEMBET-3000 instrument. A catalyst sample of 0.2 g was loaded into the quartz reactor and dried by flowing nitrogen at 150 ℃ for 1 h. The reactor was heated gradually to 800 ℃ at a heating rate of 10 ℃/min. A 10% H2-90% Ar mixture was used as the reducing gas. The water formed either by reduction or from the dehydration process was trapped by a 5A molecular sieve. The hydrogen concentration was determined by a thermal conductivity detector (TCD).

2.3 Catalytic activity test

The activity of catalysts was evaluated in a fixed-bed microreactor using dibenzothiophene as the model compound. 5.0 g of catalyst diluted with an equal amount of quartz sand was loaded and sandwiched by quartz sand in the stainless steel reactor. Prior to the HDS reaction, the catalyst was reduced with a H2flow at a rate of 100 mL/min at 300 ℃ for 3 h. After the reduction reaction, the reactor was cooled down under H2atmosphere to 150 ℃. Then DBT (2%) in decalin solution was fed into the reactor by means of a high-pressure pump. The catalytic activity was measured at different temperatures (240—300 ℃), under a hydrogen pressure of 2.0 MPa at a flow rate of 100 mL/min and a weight hourly space velocity (WHSV)of 2 h-1. Moreover, the catalysts were kept at the desired reaction temperature for at least 6 h before the product samples were obtained for analysis. The resulting samples were analyzed using an Agilent 6820 gas chromatograph provided with a HP-5(30 m×0.32 mm×0.5 μm) packed column.

Therefore, the desulfurization ratio of DBT is defined to measure the catalytic activity. Desulfurization ratio = (C0-CR-CC)×100/C0, whereC0represents the DBT concentration in the feed,CRis the DBT concentration in the HDS liquid product, andCCdescribes the concentration of all the sulfur-containing intermediates in the HDS liquid product. The main reaction products obtained from the HDS of DBT are biphenyl (BP) and cyclohexylbenzene (CHB). The selectivity (HYD/DDS) can be approximately calculated by the following equation:

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Catalytic activity and selectivity

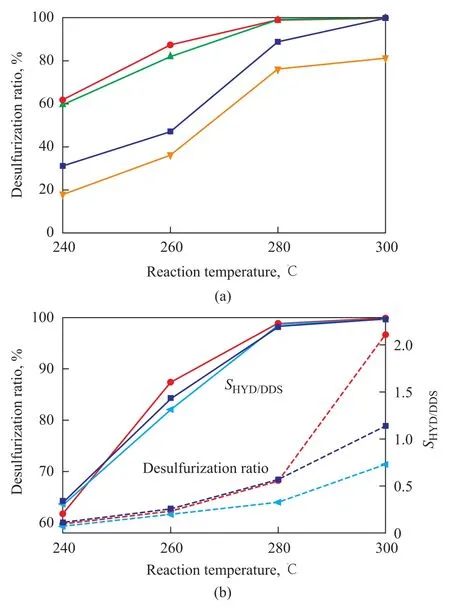

The catalysts were tested during HDS of dibenzothiophene. The effect of reaction temperature on the catalytic performance of the NPMS catalysts is shown in Figure 1(a). Temperature was normally considered as the easiest and the most effective parameter to control the hydrotreating reactions. The activity of all catalysts was enhanced by raising the reaction temperature. As the reaction temperature increased from 240 ℃ to 300 ℃, the desulfurization ratio over the NPMS-4 catalyst rose from 61.8% to 99.9%. Nevertheless, the NPMS-4 catalyst exhibited a desulfurization ratio of 98.8% at 280 ℃, which showed a superior catalytic activity at lower temperature.

The activity of the NPMS series catalysts, which contained different Ni2P loadings, increased successively up to a Ni2P loading of 4% and then decreased with further increase in the Ni2P loading. This phenomenon was probably ascribed to the bad dispersion of the promotor metal in catalysts with too high Ni2P loading, which might lead to aggregation to form a bulk phase and to decrease the utilization ratio. The desulfurization ratio over the NPMS-4 catalyst was about 2—3 times that of the NPMS-2 or NPMS-8 catalysts at 240 ℃. These results indicated that the optimal Ni2P loading was 4%.

Figure 1 Influence of reaction temperature on the desulfurization ratio and selectivity of NMPS and reference catalysts

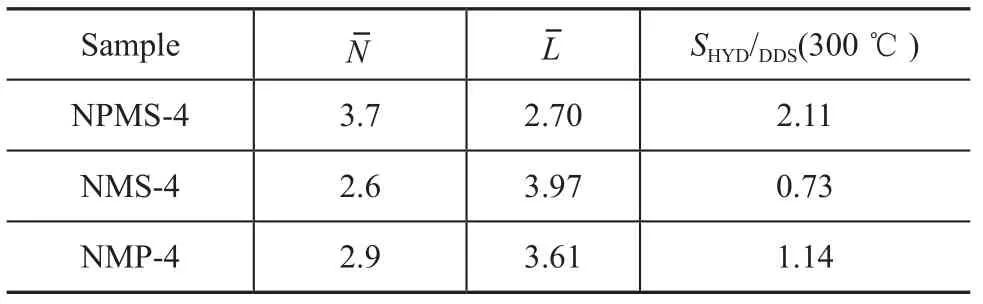

Figure 1(b) shows the catalytic activity and selectivity of the NPMS-4 catalyst and reference catalysts. The activity of NPMS-4 catalyst was close to that of the reference catalysts, but theSHYD/DDSratio was superior to that of reference catalysts. Although DBT could be almost completely converted over the NMS-4 catalyst with the sulfur totally removed, the desulfurized product was mostly BP (74%), with aSHYD/DDSratio of 0.33 at 280 ℃. So the HDS reaction of DBT catalyzed by NMS-4 catalyst undergoes mainly through the direct desulfurization (DDS) pathway rather than through the hydrogenation desulfurization (HYD) pathway, which was in good agreement with the result reported in the literature[10]. As regards the NMP-4 catalyst, the addition of phosphorus showed a small positive effect on the activity and selectivity of HDS. At different reaction temperatures theSHYD/DDSratio of NPMS-4 catalyst was 0.09, 0.23, 0.55 and 2.11, respectively. It indicated that BP was the primary product in the HDS reaction at240 ℃, and CHB was the main product of desulfurization over the NPMS-4 catalyst with an increasing reaction temperature. TheSHYD/DDSratio of NPMS-4 catalyst (2.11) was 2.9 times that of the NMS-4 catalyst (0.72) at 300 ℃. So the addition of Ni2P increased the hydrogenation activity of the MoS2catalyst.

According to the catalytic tests, the addition of nickel phosphide can promote the HYD pathway and shift the reaction mechanism from the DDS pathway to the HYD pathway. It was worth noting that the effect of nickel phosphide on the hydrogenation selectivity (SHYD/DDS) was obvious. It was generally accepted that hydrogenation and desulfurization reactions take place on separate active sites. It was concluded that the number and structure of the active sites are affected. To understand the relationship between nickel phosphide and MoS2, the NPMS-4, NMS-4 and NMP-4 catalysts were studied.

3.2 Characterization of catalysts

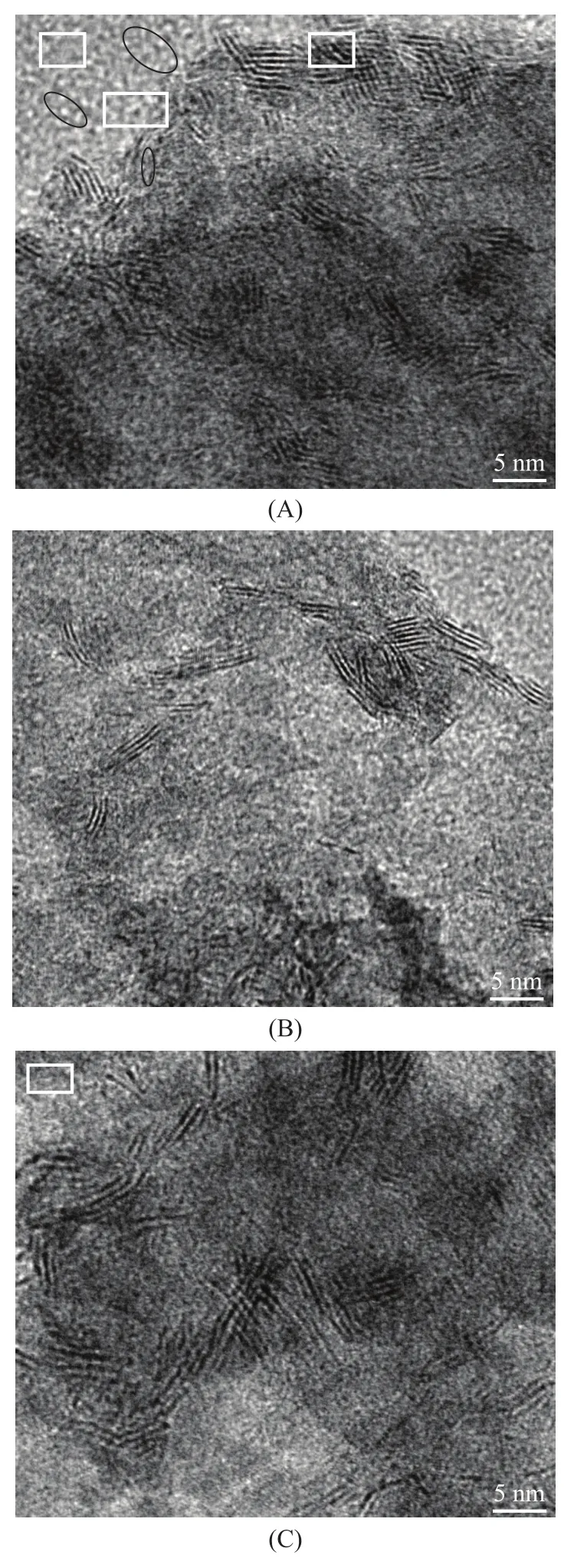

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) is a powerful technique for studying the changes in the morphology of active phases and has been applied in many studies of sul fide catalysts[11-12]. The representative HRTEM micrographs of all the catalysts are given in Figure 2. The views exhibited the well-known MoS2slab-like structure, which were homogeneously distributed on the alumina surface. The typical fringes due to MoS2crystallites with 0.61-nm interplanar distances were observed. The nanocrystalline Ni2P was not observed in the HRTEM image of NPMS-4 catalyst. But it existed in the NPMS-8 catalyst and the unsupported Ni2P-modi fied MoS2catalyst. A magni fied high resolution TEM image yielded d-spacing value of 0.221 nm for the (111) crystallographic plane of Ni2P, which was in good agreement with the reported result[7-8,13]. It indicated that the nanocrystal Ni2P existed in the NPMS catalysts.

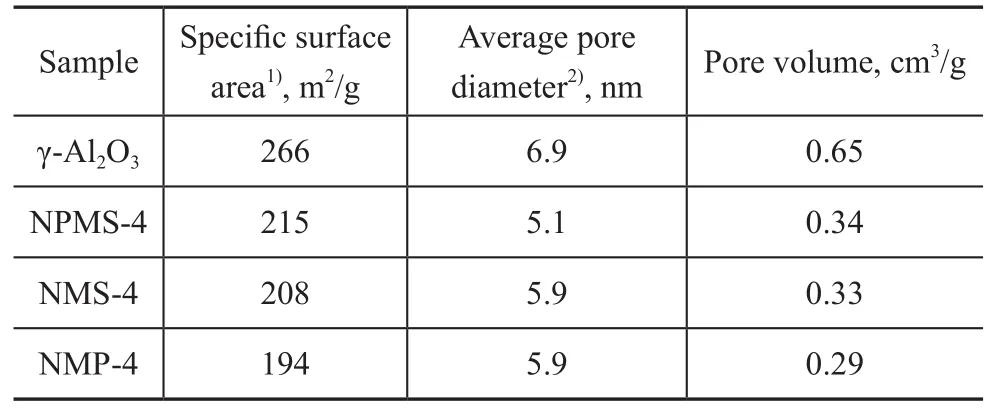

The textural characterization of all as-prepared catalysts is listed in Table 1. It can be observed that speci fic surface area, pore diameter and pore volume decreased after metal incorporation. Pore volume of the NPMS-4 catalyst was half of that of the support. This decrease indicated that the active component had been located in the pores of support. And the speci fic surface area of every catalyst was about 200 m2/g. So the introduction of Ni2P did notgreatly affect the surface of the catalyst.

Figure 2 The HRTEM images of NPMS-4 (A), NMS-4 (B) and NMP-4 (C) catalysts

Table 1 Textural properties of support and catalysts

Figure 3 presents the XRD patterns of the NPMS-4, NMS-4 and NMP-4 catalysts. In addition to the diffraction peaks of γ-Al2O3support, all samples showed typical diffraction peaks of MoS2(JCPDS 371492). The diffraction peaks at 2θ= 33.5° (101), 38.5° (103) and 58.6° (110) were attributed to MoS2. But the peak intensity of MoS2was weak, which implied that molybdenum sulfide species were either completely amorphous or composed of small crystallites. The NPMS-4 catalyst showed a little stronger intensity of the peak at 2θ= 14.1°, which was characteristic of the (002) basal plane of crystalline MoS2, indicating some differences in the particle size along the basal stacking in the “c” direction related to catalytic activity[14]. Hence, the addition of Ni2P may promote the growth of MoS2slabs along the (002) basal plane. In the patterns of all catalysts, the characteristic diffraction peaks of nickel species were not detected, owing to the low loading of nickel source on the support. The above results suggested that MoS2and nickel species were considered highly distributed on the surface of the support.

Figure 3 XRD patterns of the NMPS-4 and reference catalysts after HDS

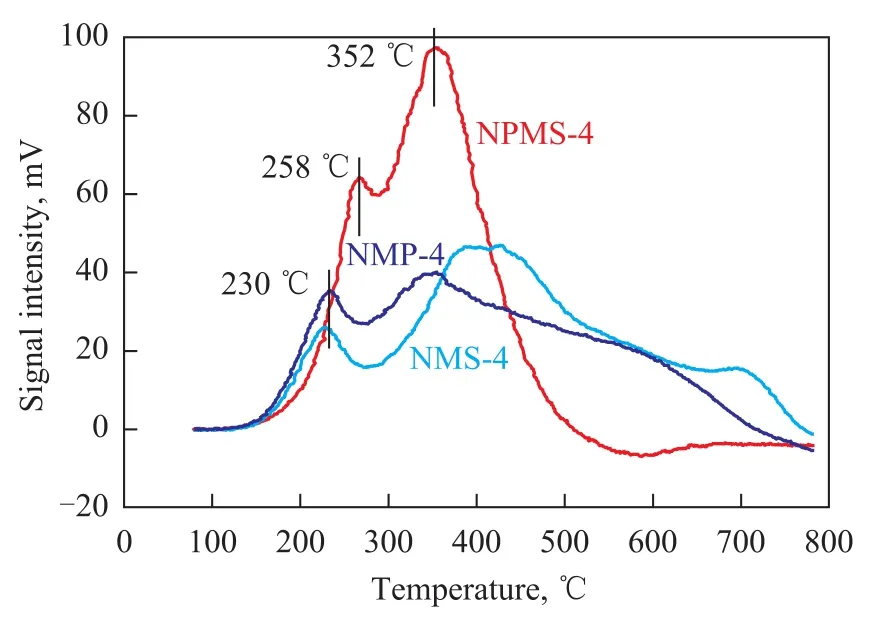

The TPR profiles of all the samples are shown in Figure 4. The profile of the NMS-4 catalyst exhibited two broad features. According to the TPR profile of NMS-4 catalyst, the broad peak at a lower temperature (230 ℃) could be ascribed to the reduction of the NiMoS phase. The broad peak at a higher temperature of 425 ℃ could be assigned to the reduction of MoS2phase. The NMP-4 catalyst had the similar TPR profiles to the NMS-4 catalyst. However, the NPMS-4 catalyst had an increase in the first peak temperature (250 ℃) with respect to the same phase in the NMS-4 catalyst. But the peak temperature for the reduction of MoS2phase was lower than that of the reference catalysts. It should be noted that NPMS-4 catalyst exhibited higher TPR peak intensity and larger total area than the reference catalysts. The peak area of H2-TPR profile indicated H2consumptions. Based on the H2consumptions, the number of sulfur vacancies formed during TPR tests could be estimated. As for the NPMS-4 catalyst, the number of sulfur vacancies appeared to be higher than that of NMS-4 and NMP-4 catalysts. It had been widely recognized that the sulfur vacancy on the edge sites of MoS2slabs was very important for HDS reaction. So it was reasonably recognized that the NPMS-4 catalyst exhibited a relatively high catalytic activity and hydrogenation desulfurization (HYD) performance.

Figure 4 H2-TPR profiles of NPMS-4 and reference catalysts

3.3 Discussion

Since MoS2structure was the active phase in the HDS reaction, its crystal size and number of stacking layers were key factors influencing both the HDS activity and selectivity[15]. Therefore, a macroscopically quantitative comparison of the length and layer number of MoS2slabs on the different catalysts was made through statistical analyses based on at least ten micrographs including 400 —500 slabs taken from different parts of each catalyst.

Table 2 The average stacking numberslab lengthof NPMS-4 catalyst and reference catalysts

Table 2 The average stacking numberslab lengthof NPMS-4 catalyst and reference catalysts

Notes: Average number of layer:,Average slab length:

?

In recent years, in order to explain the difference of hydrogenation selectivity from different catalysts, many models were proposed to study the structure-activity relationship. These models disagreed with each other because different models were only applicable to different regions and up to now there is no one model that is applicable to all catalysts and situations. But it was generally accepted that the hydrogenation selectivity was mainly associated with the degree of stacking of MoS2slabs[17].

In the Corner-Edge model developed by Topsøe[18]and Massoth[18-19], two types of sites were located on stacked MoS2slabs: the ‘corner’ sites capable of cleaving C–S bonds and the ‘edge’ sites capable of hydrogenating. According to this model, the ‘edge’ sites played a key function in hydrogenation reaction. The higher edge/ corner ratio of the NPMS-4 catalyst compared to that of the NMS-4 catalyst, as evidenced by the HRTEM images, could support the experimental results that the NPMS-4 catalyst had higher HYD selectivity. The Corner-Edge model satisfactorily explained such a high HYD selectivity for the NPMS-4 catalyst.

The research results observed by Hensen, et al.[16]also indicated that there was a relationship between the hydrogenation selectivity for HDS of DBT and the stacking degree of MoS2slabs[19]. Sulfur compounds were adsorbed on catalysts prior to the commencement of DDS or HYD reaction. As for DBT, the prerequisite for the hydrogenation was that aromatic rings were adsorbed on the ‘edge’ sites of multi-slabs MoS2by π bond coordination because of its planar molecular structure[16,20]. The distance between Mo–Mo slabs along thecaxis in MoS2structure was 0.61—0.62 nm, while an aromatic ring at least covered two MoS2slabs[21]. Thereby, a high stacking degree of MoS2slabs was beneficial to the flat adsorption and reaction of DBT on the multi-layers of MoS2slabs.

The saturation of aromatic rings was a stacking-sensitive reaction. Hence, it can be concluded that the hydrogenation selectivity was closely related to the degree of stacking of MoS2slabs, namely, the hydrogenation selectivity increased with an increasing degree of stacking of MoS2slabs. According to the conclusion, a high HYD selectivity for the NPMS-4 catalyst can also be explained.

Detailed catalyst characterization and catalyst tests showed that the presence of Ni2P increased the amount of hydrogenation sites of MoS2/Al2O3catalyst, leading to a remarkably enhanced hydrodesulfurization of DBT. It was presumed that Ni2P was anchored at the edges of MoS2slab. Hence the so-called “NiMoPS” active phase was formed. Because the amount of P element should be relatively small, the evidence of “NiMoPS” active phase would be too difficult to discriminate from the catalyst. Although there was no direct evidence shown in the paper, it will attract our attention.

4 Conclusions

In this study, a series of Ni2P-modified MoS2/γ-Al2O3catalysts were prepared via the thermal decomposition of ammonium tetrathiomolybdate and nickel hypophosphite. The addition of nickel phosphide in the MoS2catalyst supported on alumina almost affected the morphology of MoS2particles. The NPMS-4 catalyst had more layers of MoS2clusters that favored the hydrogenation reaction. And the H2-TPR results showed that the NPMS-4 catalyst could generate more sulfur vacancies. So the NPMS-4 catalyst shifted the reaction mechanism from the direct desulfurization (DDS) pathway to the hydrogenation desulfurization (HYD) pathway at 300 ℃. The catalytic performance tests showed that the NPMS-4 catalyst exhibitedthe highest dibenzothiophene hydrodesulfurization activity, and the hydrogenation selectivity of the NPMS-4 catalyst was 2.9 times as much as that of the reference (NMS-4) catalyst.

Acknowledgements:This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (No. 1408085QB44) and the Natural Science Foundation of Educational Committee of Anhui Province (No. KJ2013B243), and the Youth Foundation of Huaibei Normal University (2013xqz01).

[1] Song C. An overview of new approaches to deep desulfurization for ultra-clean gasoline, diesel fuel and jet fuel[J]. Catal Today, 2003, 86(1/4): 211-263

[2] Liu Di, Liu Chenguang. Deep hydrodesulfurization of diesel fuel over diatomite-dispersed NiMoW sulfide catalyst[J]. China Petroleum Processing and Petrochemical Technology, 2013, 15(4): 38-43

[3] Knudsen K G, Cooper B H, Topsøe H. Catalyst and process technologies for ultra low sulfur diesel[J]. Appl Catal A: Gen,1999, 189(2): 205-215

[4] Niquille-Röthlisberger A, Prins R. Hydrodesulfurization of 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene over Pt, Pd, and Pt-Pd catalysts supported on amorphous silica–alumina[J]. Catal Today, 2007, 123(1/4): 198-207

[5] Pessayre S, Geantet C, Bacaud R, et al. Platinum doped hydrotreating catalysts for deep hydrodesulfurization of diesel fuels[J]. Ind Eng Chem Res, 2006, 46(12): 3877-3883

[6] Liu L, Li G, Liu D, et al. Preparation and catalytic performance of transition metal posphides[J]. Progress in Chemistry, 2010, 22(9): 1701-1708

[7] Shi G, Shen J. New synthesis method for nickel phosphide nanoparticles: Solid phase reaction of nickel cations with hypophosphites[J]. J Mater Chem, 2009, 19(16): 2295-2297

[8] Guan Q, Li W, Zhang M, et al. Alternative synthesis of bulk and supported nickel phosphide from the thermal decomposition of hypophosphites[J]. J Catal, 2009, 263(1): 1-3

[9] McDonald J W, Friesen G D, Rosenhein L D, et al. Syntheses and characterization of ammonium and tetraalkylammonium thiomolybdates and thiotungstates[J]. Inorg Chim Acta, 1983, 72(1): 205-210

[10] Bataille F, Lemberton J L, Michaud P, et al. alkyldibenzothiophenes hydrodesulfurization-promoter effect, reactivity, and reaction mechanism[J]. J Catal, 2000, 191 (2): 409-422

[11] Payen E, Hubaut R, Kasztelan S, et al. Morphology study of MoS2- and WS2-based hydrotreating catalysts by highresolution electron microscopy[J]. J Catal, 1994, 147 (1): 123-132

[12] Ramírez J, Castillo P, Benitez A, et al . Electron microscopy study of NiW/Al2O3-F(x) sulfided catalysts prepared using oxisalt and thiosalt precursors[J]. J Catal, 1996, 158 (1): 181-192

[13] Shi G, Shen. Mesoporous carbon supported nickel phosphide catalysts prepared by solid phase reaction[J]. Catal Commun, 2009, 10 (13): 1693-1696

[14] Berhault G, Perez De la Rosa M, Mehta A, et al. The single-layered morphology of supported MoS2-based catalysts--The role of the cobalt promoter and its effects in the hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene[J]. Appl Catal A:Gen, 2008, 345 (1): 80-88

[15] Yin Hailiang, Zhou Tongna, Liu Chenguang. Effect of phosphorus on the interaction between active component and carrier of NiMo/Al2O3catalysts[J]. Petroleum Processing and Petrochemicals, 2012, 43(7): 33-37 (in Chinese)

[16] Hensen E J M, Kooyman P J, van der Meer Y, et al. The relation between morphology and hydrotreating activity for supported MoS2particles[J]. J Catal, 2001, 199 (2): 224-235

[17] Tye C T, Smith K J. Hydrodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene over exfoliated MoS2catalyst[J]. Catal Today, 2006, 116 (4):461-468

[18] Topsøie H, Candia R, Topsøe N, et al. On the state of the Co-Mo-S model[J]. Bull Soc Chim Belg, 1984, 93(8/9) 783-806

[19] Massoth F E, Muralidhar G, Shabtai J. Catalytic functionalities of supported sulfides: II. Effect of support on Mo dispersion[J]. J Catal, 1984, 85(1): 53-62

[20] Alonso G, Berhault G, Aguilar A, et al. Characterization and HDS activity of mesoporous MoS2catalysts prepared by in situ activation of tetraalkylammonium thiomolybdates[J]. J Catal, 2002, 208 (2): 359-369

[21] Vradman L, Landau M V. Structure–function relations in supported Ni–W sulfide hydrogenation catalysts[J]. Catal lett, 2001, 77 (1/3): 47-54

Received date: 2014-04-22; Accepted date: 2014-07-17.

Liu Lihua, Telephone: +86-561-3802235; E-mail: chemliulh@chnu.edu.cn.

杂志排行

中国炼油与石油化工的其它文章

- Comparative Studies on Low Noise Greases Operating under High Temperature Oxidation Conditions

- A Method for Crude Oil Selection and Blending Optimization Based on Improved Cuckoo Search Algorithm

- Experimental Research on Pore Structure and Gas Adsorption Characteristic of Deformed Coal

- Mathematical Model of Natural Gas Desulfurization Based on Membrane Absorption

- Effects of Airflow Field on Droplets Diameter inside the Corrugated Packing of a Rotating Packed Bed

- Synthesis of Phenyl Acetate from Phenol and Acetic Anhydride over Synthetic TS-1 Containing Template