北京及广州3岁以上居民焙烤食品中反式脂肪酸摄入量评估

2014-05-14李建文刘爱东刘兆平

李建文,刘爱东,张 磊,刘兆平,李 宁

(卫生部食品安全风险评估重点实验室,国家食品安全风险评估中心,北京 100022)

反式脂肪酸(trans-fatty acids,TFA)是碳链上含有一个或以上非共轭反式双键的不饱和脂肪酸及所有异构体的总称[1]。人体试验研究表明,长期过量摄入TFA可能升高低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(lowdensity lipocholesterol,LDLC)水平,同时降低高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(high-density lipoptrotein cholesterol HDLC)水平[2-6],导致总胆固醇(total cholesterol,TC)与 HDLC[7]或 LDLC 与 HDLC 的比值随之升高[5,8]。目前已有充足证据表明,膳食总 TFA摄入量越高,心血管疾病风险越大[9-15],但 TFA 与其他疾病的关系尚需进一步研究确证。WHO建议,人群TFA供能比应小于1%。

TFA有工业和天然两个来源。工业来源包括油脂的部分氢化、油脂的精炼加工以及加工食品时油温过高;反刍动物奶、肉及制品,是TFA的天然来源。焙烤食品加工过程中,可能添加含TFA的氢化油脂以满足特定的食品加工工艺的需求,天然来源的TFA也可能存在。我国2013年实施的《食品安全国家标准预包装食品营养标签通则》中规定,食品配料含有或生产过程中使用了氢化和(或)部分氢化油脂时,在营养成分表中还应标示出反式脂肪(酸)的含量(强制标示),TFA含量≤0.3 g/100 g(或100 mL)时,可以标示为无或不含反式脂肪(酸)。

本研究旨在了解我国焙烤食品TFA含量及变化趋势,并以WHO的建议(<1%)为评价标准评估焙烤食品TFA的健康风险,为风险管理和风险交流提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 样品采集

在西安、成都、北京、上海、广州5个城市的大中型超市、农贸批发零售市场,现场制售食品摊点等采样点采集焙烤食品(饼干、糕点、面包、月饼等)样品。采样时根据市场调查,同种类食品按照食品销量大小,对前位销量的品牌进行取样。样品采集的基本原则按照《食品卫生检验标准理化部分总则》(GB/T 5009.1)执行[16]。

1.2 TFA 检测

样品的专项检测工作由5个检测机构完成,包括中国疾病预防控制中心营养与食品安全所、北京市营养源研究所、国家食品质量监督检验中心、江南大学、南昌大学。所有食品的检测方法等效采用AOAC996.06的《食品中总脂肪、饱和脂肪(酸)、不饱和脂肪(酸)的测定 水解提取气相色谱法》(GB/T 22223-2008)[17]或《食品中反式脂肪酸的测定 气相色谱法》(GB/T 22110-2008)[18]。

1.3 其他来源TFA含量数据的使用

本次评估,除了以上2011年检测数据之外,还纳入了部分科研机构、企业、协会提供的食品中TFA检测数据(以气相色谱法测定)以及公开发表的文献数据。两部分数据经质量审核,以2007年为界进行t检验。若数据之间存在统计学差异,则使用2007年之后的数据,否则,使用全部数据进行评估。

1.4 食物聚类

由于含量分析的需要,焙烤食品被划分为17小类(包括月饼),但计算焙烤食品消费量,以及TFA摄入量和供能比时,需要根据消费量数据对含量数据重新聚类。本次评估,焙烤食品最终聚为6类,即饼干、糕点、牛角/羊角面包、奶油/黄油面包、其他面包、月饼。

1.5 食物消费量数据

本次评估所采用的消费量数据来源于2002年中国居民营养与健康状况调查和2011年“北京、广州两市3岁及以上人群含TFA食物消费状况典型调查”数据库,分别包括了全国68 959名、10 533名调查对象的食物消费量数据。

1.6 膳食暴露评估方法

本次评估人群分组如下:全人群,3~6岁(3~),7~12岁(7~),13~17岁(13~),18岁以上(18~)。评估时采用简单分布模型(确定性评估),计算每个个体每日TFA的摄入水平(每天摄入TFA的克数),并利用 TFA的能量折算系数(9 kcal·g-1)和个体的膳食摄入总能量,计算TFA的供能比。

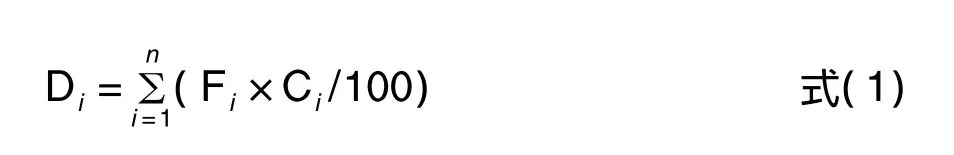

TFA摄入量的计算公式为:

式中:Di为某个体每日的TFA摄入量,单位为 g·d-1,Fi为某个体第 i种食物的消费量,单位为 g·d-1,Ci为第 i种食物中 TFA 的平均含量,单位为g/100 g。

TFA供能比的计算公式为:

式中:E为某个体每日的TFA供能比(%),DI为某个体每日的TFA摄入量,单位为g·d-1,DE为某个体摄入的膳食总能量,单位为kcal,9为TFA能量折算系数,单位为kcal·g-1。

评估TFA摄入的潜在风险时,以WHO建议的TFA供能比<1%为衡量标准。

1.7 统计学分析

以均值和百分位数描述各类食品中TFA的含量、分布;采用t检验比较2007年前后各类焙烤食品中的TFA含量差异;以SAS 9.1对膳食消费量数据及不同人群TFA摄入量进行统计分析。

2 结果

2.1 不同年份检测数据的差异分析

对2007年前及2007-2012年焙烤食品中TFA检测数据进行差异性分析,结果见表1。曲奇饼干、蛋糕、酥性饼干的TFA含量2007年前后无统计学差异,故用全部数据进行分析;而夹心饼干和派,选用2007年以后的数据。

Tab.1 Comparison of trans-fatty acids(TFA)contents in bakery products before and after the year 2007

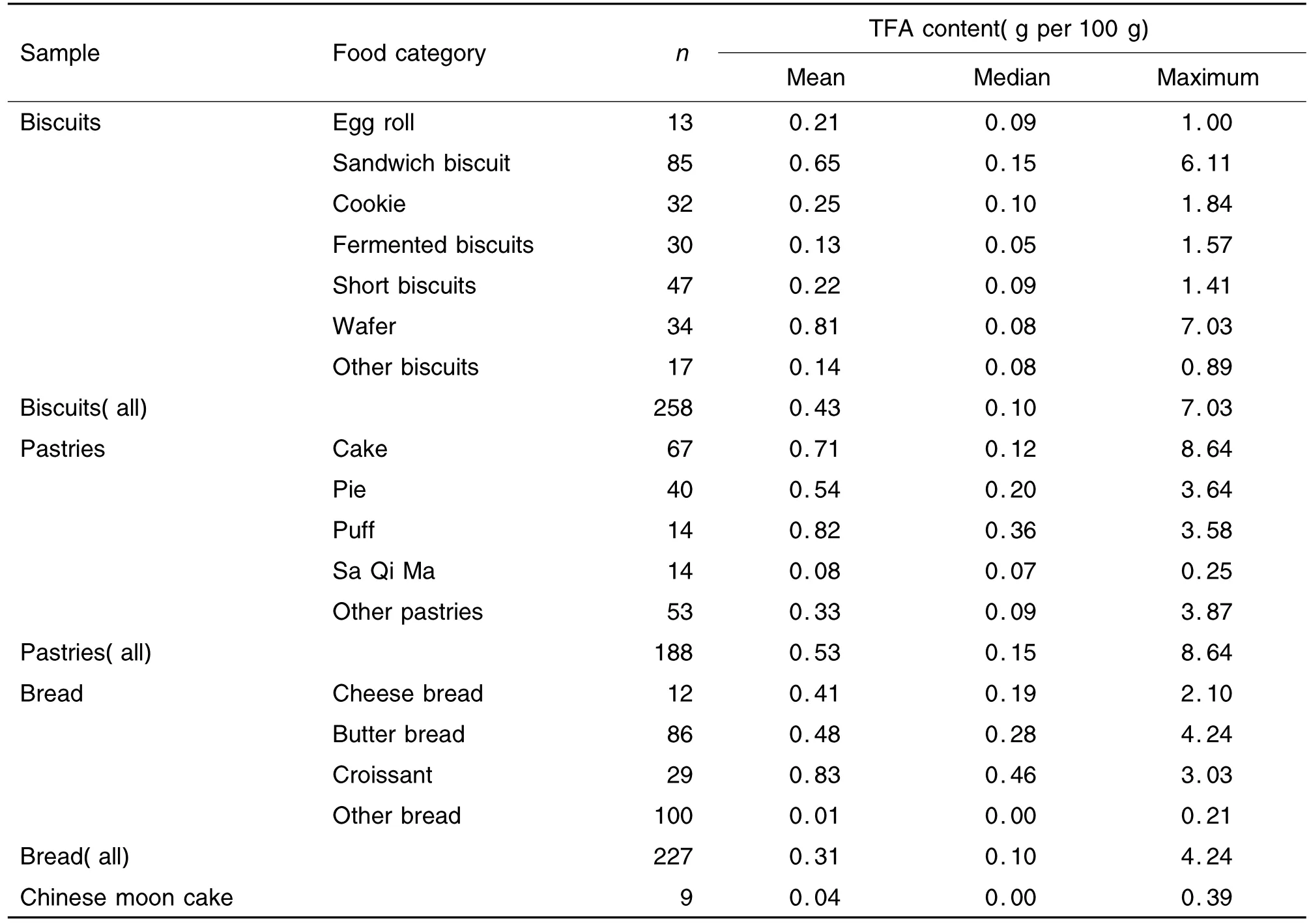

2.2 焙烤食品中反式脂肪酸的含量

682种焙烤食品中TFA的含量分析时,将饼干、糕点、面包细分为以下各类,含量见表2。结果表明,饼干中夹心饼干、威化饼干,糕点中的蛋糕、泡芙和派,面包中的牛角/羊角面包TFA含量较高,平均值均超过0.50 g/100 g,最高为牛角/羊角面包,含量达0.83 g/100 g。在17类焙烤食品中,有8类食品的TFA含量最大值超过3.0 g/100 g,说明有个别食品的TFA含量较高。

Tab.2 TFA contents in various bakery food categories in China

对682种焙烤食品TFA含量分布进行分析结果显示,TFA含量≤0.3 g/100 g的样品占72.7%,0.3 g/100 g <TFA≤0.5 g/100 g 的样品占9.2%;TFA>1 g/100 g的样品占全部样品的10.9%。

对饼干、面包、糕点3类焙烤食品,以及其部分亚类的含量构成统计分析的结果见表3。TFA≤0.3 g/100 g样品占大部分。尽管威化饼干中含有饼干中TFA含量的最大值,但34份威化样品中,TFA含量在0.3 g/100 g(含0.3)以下的样品比例为88.2%。这说明大部分的威化样品TFA平均含量较低,而部分高含量样品使威化类样品的平均值增高。TFA平均含量较高的几类食品,按大于1 g/100 g的样品占比例的大小,由高到低分别为牛角/羊角面包(31.0%)、夹心饼干(21.2%)、蛋糕(16.4%)和奶油面包(14.0%)。

Tab.3 Proportions of samples within different ranges of TFA contents in all biscuits,bread,and pastry and in the relative subcatergories

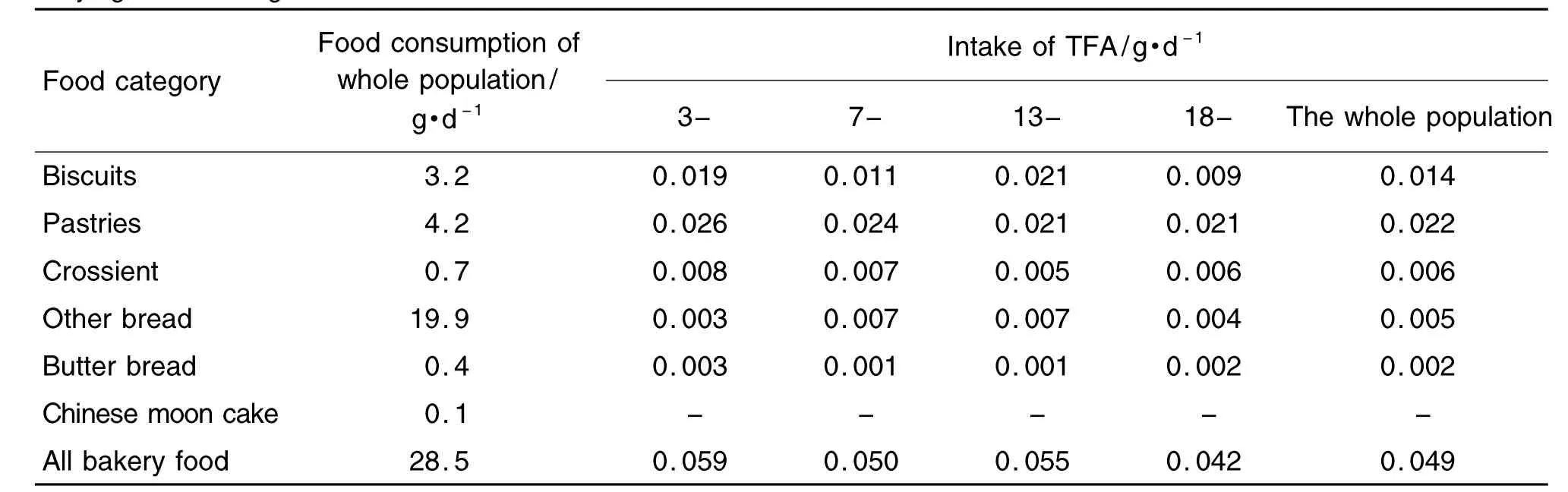

年北京及广州地区不同人群各类焙烤食品TFA摄入量

2011年,北京和广州全人群,通过所有焙烤食品摄入的TFA的量很低,仅为0.049 g。从各年龄组来看,虽然3~6岁年龄组TFA摄入量最高,但摄入量仅为0.059 g,其中通过糕点摄入的TFA最多,为0.026 g(表4)。

2.4 不同人群TFA供能比

表5结果显示,无论是全人群还是各年龄组,经焙烤食品摄入TFA的供能比均很低。全人群经焙烤食品摄入的TFA,仅占膳食总能量的0.027%,3~6岁人群最高,占膳食总能量的0.041%。

2.5 不同焙烤食品对TFA摄入的贡献率

本次评估中各类焙烤食品对北京、广州两城市居民膳食TFA摄入的贡献率见表6。全人群焙烤食品TFA贡献率为8.88%,3~6岁年龄组焙烤食品TFA贡献率最高,为12.10%,其次为13~17岁年龄组,9.11%。所有焙烤食品中,糕点对TFA的贡献最高。

Tab.4 Average intakes of TFA from various bakery foods among different Chinese populations in survey 2011 in Beijing and Guangzhou

Tab.5 TFA intakes in different polpulations in survey 2011 in Beijing and Guangzhou

Tab.6 Contribution of TFA of various food among different populations in survey 2011 in Beijing and Guangzhou

3 讨论

我国部分学者已对食品原料、油脂、焙烤食品等食物中的TFA含量进行了研究,为本次评估提供了一定的参考资料[19-22]。2007年后我国夹心饼干、派TFA含量均值比2007年前显著降低(分别从2.55 g/100 g,2.05 g/100 g 降至0.65 g/100 g,0.54 g/100 g),而曲奇和酥性饼干,尽管含量也有所下降,但差异并不显著。这些食物中TFA含量下降的趋势与国际焙烤食品TFA含量变化趋势相符[23-26]。国际上 TFA含量的下降与TFA管理措施相关[27],这些措施迫使焙烤食品行业进行配方的改良,使焙烤食品中 TFA 含量降低[28-30]。我国TFA含量下降的原因可能与2007年后,公众媒体对TFA的密切关注、食品企业作出相应的配方调整,以应对我国《食品安全国家标准预包装食品营养标签通则》的颁布(2011年10月12日)和生效(2013年1月1日)有关。

我国全人群通过焙烤食品摄入的TFA量很低(平均0.049 g·d-1),供能比也仅为 0.027%。焙烤食品的消费量和TFA贡献率,小于18岁的各年龄组高于18岁及以上年龄组,提示在焙烤食品方面,大城市低年龄组人群比18岁及以上年龄组的食用倾向性更强。北京与广州全人群及除18岁之外的各年龄组TFA贡献率(8.9% ~12.1%)和澳大利亚(8% ~17%)和新西兰(8% ~11%)近似,低于日本(30岁以上人群组18% ~19.1%)[31]和美国(3岁以上人群平均19%)[32]。鉴于我国目前部分食物类别如牛角/羊角面包、泡芙、威化、夹心饼干中确实有较高含量的TFA存在,而TFA的摄入量和零食、蛋糕和糕点正相关[33],蛋糕、曲奇、派和糕点这些焙烤食品是TFA的重要来源[32],建议风险管理部门加强对以上各类食物的监管;食品工业界进一步减少含TFA的氢化油脂在焙烤食品中的应用并加速TFA替代油脂的开发。

作为首次开展的较为全面的焙烤食品TFA摄入量评估,本次评估尚存在一定的不确定性。如采样时未能覆盖焙烤食品的所有种类;又如计算供能比时,假设部分食品如生鲜蛋类、鱼类、除牛羊肉之外的生鲜畜禽肉的TFA含量为零,牛油、羊油、猪油的消费量为零,则可能低估总TFA摄入,进而高估焙烤食品贡献率。

[1] CAC.Report of the Thirty-Fourth Session of the Codex Committee on Food Labelling[R].In WHO Technical Report Series 2006.

[2] Mensink RP,Katan MB.Effect of dietary trans-fatty acids on high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in healthy subjects[J].N Engl J Med,1990,323(7):439-445.

[3] Zock PL,Katan MB.Hydrogenation alternatives:effects of trans-fatty acids and stearic acid versus linoleic acid on serum lipids and lipoproteins in humans[J].J Lipid Res,1992,33(3):399-410.

[4] Judd JT,Clevidence BA,Muesing RA,Wittes J,Sunkin ME, PodczasyJJ. Dietarytrans-fatty acids:effects on plasma lipids and lipoproteins of healthy men and women[J].Am J Clin Nutr,1994,59(4):861-868.

[5] Almendingen K,Jordal O,Kierulf P,Sandstad B,Pedersen JI.Effects of partially hydrogenated fish oil,partially hydrogenated soybean oil,and butter on serum lipoproteins and Lp[a]in men[J].J Lipid Res,1995,36(6):1370-1384.

[6] Judd JT,Baer DJ,Clevidence BA,Kris-Etherton P,Muesing RA,Iwane M.Dietary cis-and transmonounsaturated and saturated FA and plasma lipids and lipoproteins in men[J].Lipids,2002,37(2):123-131.

[7] Lichtenstein AH,Ausman LM,Jalbert SM,Schaefer EJ.Effects of different forms of dietary hydrogenated fats on serum lipoprotein cholesterol levels[J].N Engl J Med,1999,340(25):1933-1940.

[8] Müller H,Jordal O,Kierulf P,Kirkhus B,Pedersen JI.Replacement of partially hydrogenated soybean oil by palm oil in margarine without unfavorable effects on serum lipoproteins[J].Lipids,1998,33(9):879-887.

[9] Mauger JF,Lichtenstein AH,Ausman LM,Jalbert SM,Jauhiainen M,Ehnholm C,et al.Effect of different forms of dietary hydrogenated fats on LDL particle size[J].Am J Clin Nutr,2003,78(3):370-375.

[10] Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE,Colditz GA,Speizer FE,Rosner BA,et al.Intake of trans-fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease among women[J].Lancet,1993,341(8845):581-585.

[11] Ascherio A,Rimm EB,Giovannucci EL,Spiegelman D,Stampfer M,Willett WC.Dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease in men:cohort follow up study in the United States[J].BMJ,1996,313(7049):84-90.

[12] Hu FB,Stampfer MJ,Manson JE,Rimm E,Colditz GA,Rosner BA,et al.Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women[J].N Engl J Med,1997,337(21):1491-1499.

[13] Pietinen P,Ascherio A,Korhonen P,Hartman AM,Willett WC,Albanes D,et al.Intake of fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease in a cohort of Finnish men.The Alpha-Tocopherol,Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study[J].Am J Epidemiol,1997,145(10):876-887.

[14] Oomen CM,Ocké MC,Feskens EJ,van Erp-Baart MA,Kok FJ,Kromhout D.Association between trans-fatty acid intake and 10-year risk of coronary heart disease in the Zutphen Elderly Study:a prospective population-based study[J].Lancet,2001,357(9258):746-751.

[15] Mozaffarian D, Clarke R. Quantitative effects on cardiovascular risk factors and coronary heart disease risk of replacing partially hydrogenated vegetable oils with other fats and oils[J].Eur J Clin Nutr,2009,63(Suppl 2):S22-S33.

[16] Ministry ofHealth,People's Republic of China,Standardization Administration of the People's Republic of China.GB/T 5009.1-2003 Methods of food hygienic analysis-Physical and chemical section- General principles(GB/T 5009.1-2003《中华人民共和国国家标准 食品卫生检验方法 理化部分 总则》)[S].Beijing:China Standards Press,2004.

[17] General Administration of Quality Supervision,Inspection and Quarantine of the People's Republic of China,Standardization Administration of the People's Republic of China.GB/T 22223-2008 Determination of total fat,saturated fat,and unsaturated fat in foods-hydrolytic extraction-gas chromatograph(GB/T 22223-2008《中华人民共和国国家标准食品中总脂肪、饱和脂肪(酸)、不饱和脂肪(酸)的测定水解提取气相色谱法》)[S].Beijing:China Standards Press,2008.

[18] General Administration of Quality Supervision,Inspection and Quarantine of the People's Republic of China,Standardization Administration of the People's Republic of China.GB/T 22110-2008 Determination of trans fatty acids in foods-Gas chromatographic method(GB/T 22110-2008《中华人民共和国国家标准食品中反式脂肪酸的测定气相色谱法》)[S].Beijing:China Standards Press,2008.

[19] Deng ZY,Liu R,Liu DM,Li J,Hu JN,Fan YW.Investigation of trans fatty acids in the raw food composed Chinese diet[J].J Chin Inst Food Sci Technol(中国食品学报),2010,10(4):38-47.

[20] Fu H,Zhao L,Yang L,Li Z,Lai DH,Wang ZW,et al.Survey of trans-fatty acids in foods in Chinese market[J].J Chin Inst Food Sci Technol(中国食品学报),2010,10(4):48-52.

[21] Song ZH,Wang XG,Jin QZ,Liu YF,Shan L.Study on the distribution of trans-fatty acids in oilcontaining foods[J].Cereal Oil Process(粮油加工),2008,(10):67-68,69.

[22] Ke RH,Yin ZB,Zhang Y,Yin JJ.Determination of trans fatty acids content in baked food using gas chromatography[J].Food Res Dev(食品研究与开发),2010,31(12):165-168.

[23] Leth T, Jensen HG, Mikkelsen AA,Bysted A.The effect of the regulation on trans-fatty acid content in Danish food[J].Atheroscler Suppl,2006,7(2):53-56.

[24] Van Camp D,Hooker NH,Lin CT.Changes in fat contents of US snack foods in response to mandatory trans fat labelling[J].Public Health Nutr,2012,15(6):1130-1137.

[25] Lee JH, Adhikari P, Kim SA, Yoon T,Kim IH,Lee KT.Trans-fatty acids content and fatty acid profiles in the selected food products from Korea between 2005 and 2008[J].J Food Sci,2010,75(7):C647-C652.

[26] Stampfer MJ,Sacks FM,Salvini S,Willett WC,Hennekens CH.A prospective study of cholesterol,apolipoproteins,and the risk of myocardial infarction[J].N Engl J Med,1991,325(6):373-381.

[27] Downs SM,Thow AM,Leeder SR.The effectiveness of policies for reducing dietary trans fat:a systematic review of the evidence[J].Bull World Health Organ,2013,91(4):262H-269H.

[28] Menaa F,Menaa A,Menaa B,Tréton J.Transfatty acids,dangerous bonds for health?A background review paper of their use,consumption,health implications and regulation in France[J].Eur J Nutr,2013,52(4):1289-1302.

[29] Ansorena D, Echarte A,Ollé R, Astiasarán I.2012:No trans fatty acids in Spanish bakery products[J].Food Chem,2013,138(1):422-429.

[30] Aroa A,Amaralb E,Kestelootc H,Rimestadd A,Thamme M,van Poppel G.Trans-fatty acids in french fries,soups,and snacks from 14 european countries:The TRANSFAIR Study[J].J Food Compos Anal,1998,11(2):170-177.

[31] Yamada M,Sasaki S,Murakami K,Takahashi Y,Okubo H,Hirota N,et al.Estimation of trans fatty acid intake in Japanese adults using 16-day diet records based on a food composition database developed for the Japanese population[J].J Epidemiol,2010,20(2):119-127.

[32] Kris-Etherton PM, Lefevre M, Mensink RP,Petersen B,Fleming J,Flickinger BD.Trans fatty acid intakes and food sources in the U.S.population:NHANES 1999-2002[J].Lipids,2012,47(10):931-940.

[33] Kawabata T,Shigemitsu S,Adachi N,Hagiwara C,Miyagi S,Shinjo S,et al.Intake of trans fatty acid in Japanese university students[J].J Nutr Sci Vitaminol(Tokyo),2010,56(3):164-170.