Pancreaticoduodenectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy combined with superior mesentericportal vein resection for elderly cancer patients

2014-05-04JunWeiSunPingPingZhangHeRenandJiHuiHao

Jun-Wei Sun, Ping-Ping Zhang, He Ren and Ji-Hui Hao

Tianjin, China

Pancreaticoduodenectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy combined with superior mesentericportal vein resection for elderly cancer patients

Jun-Wei Sun, Ping-Ping Zhang, He Ren and Ji-Hui Hao

Tianjin, China

BACKGROUND:There is an increasing frequency of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) and PD with superior mesenteric-portal vein (SMPV) resection in elderly cancer patients. The study aimed to investigate the safety and the survival benefits of PD and PD with SMPV resection in patients under or over 70 years of age.

METHODS:We divided 296 patients who had undergone PD and PD with SMPV resection into two groups according to their ages: under or over 70 years old. The clinical data were compared between the two groups.

RESULTS:Preoperative comorbidity rate was higher in elder patients than in younger patients (P=0.001). The elder patients were more likely to have postoperative complications (P=0.003). Specifically, complications above grade III were more likely to occur in the elderly patients (P=0.030). Multivariable analysis showed that age (adjusted OR=2.557,P=0.015) and hypertension (adjusted OR=2.443,P=0.019) were independent predictors of postoperative complications. There was no significant difference in the mortality rates between the two groups (P=0.885). In the PD with SMPV resection series, elderly patients were more likely to have postoperative complications (P=0.063), but this difference was not statistically significant. There was no difference in the survival rate of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma between the two groups. Operation type (PD vs PD with SMPV resection) did not affect the survival of patients.

CONCLUSIONS:Age affects postoperative complication in patients undergoing either PD or PD with SMPV resection. However, extensive experience and advanced perioperative management lower the complication rate to an acceptablelimit. Hence it is safe and worthwhile to perform PD for elderly patients. Because of low numbers in the SMPV subset, we could not conclude whether PD with SMPV resection is feasible in elderly patients.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:428-434)

pancreaticoduodenectomy;

elderly;

cancer;

outcomes

Introduction

Many countries are experiencing aging populations. The Sixth Nationwide Population Census of China reports that 8.87% of the Chinese population are older than 65 years. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) remains the only potentially curative treatment for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and periampullary malignant tumors (ampullary carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma of the distal common bile duct, and duodenal adenocarcinoma), and these tumors have the highest incidences in patients aged between 60 and 80 years.[1,2]With the acceleration of the aging population, we have observed an increasing trend in these elderly people who required PD to treat their cancers with a reasonably good outcome. In addition, with the advantage of being able to achieve a margin-negative resection, PD with superior mesenteric-portal vein (SMPV) resection has been gradually accepted in the elderly in recent decades.[3]Because of the accumulation of surgical experience and advances in healthcare in highvolume centers, surgeons are consequently encouraged to accept this approach in the elderly as aggressively as they do in younger patients. This phenomenon creates a fundamental dilemma for surgeons when considering the fragility of elderly patients and their concomitant illnesses, which may bring about higher morbidity and mortality rates. Until now there have been dividedopinions on whether PD is justified in the elderly.[2,4,5]However, there are few reports about the influence of age on the safety and the survival benefits of PD with SMPV resection. In this study, we retrospectively compared the outcomes between the elder and younger patients who had undergone PD for cancer. In addition, we evaluated the outcomes of PD with SMPV resection and reconstruction in elderly patients so as to determine whether it is safe and worthwhile for them to undergo PD with SMPV resection.

Methods

Protocol

We performed a retrospective review of the prospective database sourced from our hospital. The medical records of all 296 patients who had undergone PD for cancer from March 2000 to December 2010 were analyzed. Although there is currently no unanimous definition of an elderly patient, most studies defined as the patient aged ≥70 years.[2,5,6]We divided our patients into two groups according to their ages, with 70 as the dividing line.

Perioperative management

Before the operation, the 296 patients underwent physical examination, chest radiography, helical computed tomography and abdominal angiography. The comorbidity status was evaluated objectively using the Charlson comorbidity index,[7]which is a measure of comorbidity used to standardize the evaluation of surgical patients. Afterwards, these data were reassessed for resectability by surgical oncologists. PD was selected as the standard procedure. The surgical technique was standardized with systematic lymphadenectomy.

Postoperative management was routinely standardized. In our institute, the patients were routinely admitted to the ICU for one week. Antibiotics were administered for three days. H2blockers and octreotide were given for one week. The quality and quantity of the fluid drained from the nasogastric decompression tube and the other drains were recorded daily. Gemcitabine was taken as the first-line chemotherapeutic regimen of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after operation.

Data collection

Demographic characteristics, clinical presentation, comorbidity, intraoperative data, hospital stay, pathologic data, postoperative data, and overall survival were compared between the two groups. Postoperative 30-day complications and mortality were analyzed. Any complications after the operation have been documented, including pancreatic fistula, biliary anastomotic fistula, post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH), infections, delayed gastric emptying (DGE), adhesive intestinal obstruction, deep venous thrombosis and abdominal collections. All complications were graded according to the Clavien classification,[8]i.e. grade I: no pharmacological treatment or interventions; grade II: pharmacological treatment; grade III: intervention; grade IV: life-threatening complication; and grade V: patient death. The definitions and classifications of DGE, pancreatic fistula and PPH were managed according to the standards proposed by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS).[9-11]Abdominal collections were identified when therapeutic drainage was performed under the radiological guidance.

Surgical technique and protocol in PD with SMPV resection

In the secondary analysis, we divided the patients who had undergone PD with SMPV resection into two groups by using the age of 70 years as a cut-off value. If the tumor was adjacent to the SMPV, surgeons needed to determine whether it was feasible for SMPV resection and reconstruction according to the following criteria: 1) the absence of extra-pancreatic involvement; 2) evidence of tumor adhesion to the SMPV; 3) no involvement of the superior mesenteric artery, common hepatic artery or celiac axis; and 4) the absence of lymph node metastasis to the para-aortic area. SMPV resection was performed in two ways: a wedge excision and a segmental resection. Of the 59 patients who underwent venous resection, 47 patients were operated on with a wedge excision of the SMPV (1-2 cm) and primary closure using a continuous running suture of 5-0 prolene. Segmental resection was carried out in 12 patients, of whom 7 were reconstructed with Gore-tex (Medical Products, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), 4 directly with an end-to-end anastomosis and 1 with an autologous vein. The other procedures were the same as above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0. The values are reported as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR). Quantitative variables were compared using Student'sttest or the Mann-WhitneyUtest. Qualitative variables were expressed by number and percentage and compared using the two-tailed Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Binary multiple linear logistic regression analysis in a stepwise forward manner was carried out inmultivariate analysis. Statistical significance was defined asP<0.05; a two-sided test was performed. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test at the level ofP<0.05.

Results

Demographic and preoperative clinical data

In the 296 patients who had undergone PD, their mean age was 59.2±11.3 years. Eighty-eight (29.7%) patients were aged ≥70 years. There were no significant differences in gender distribution, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, tobacco use, clinic presentation, and preoperative laboratory values between the two groups. It has been determined that the elderly patients tend to have a higher preoperative comorbidity (62.5% vs 41.3%;P=0.001), particularly those patients with hypertension (P<0.001), diabetes mellitus (P=0.003) and coronary artery disease (P<0.001). In addition, the number of patients suffering from two or more comorbidities was higher in the elder group (P<0.001), whereas younger patients were more likely to have a history of ethanol use (P=0.008) (Table 1). Forty-five patients in the younger patients scored 1 or more in the Charlson comorbidity index, which was not different from that of the elder group (n=27; 30.7%;P=0.097).

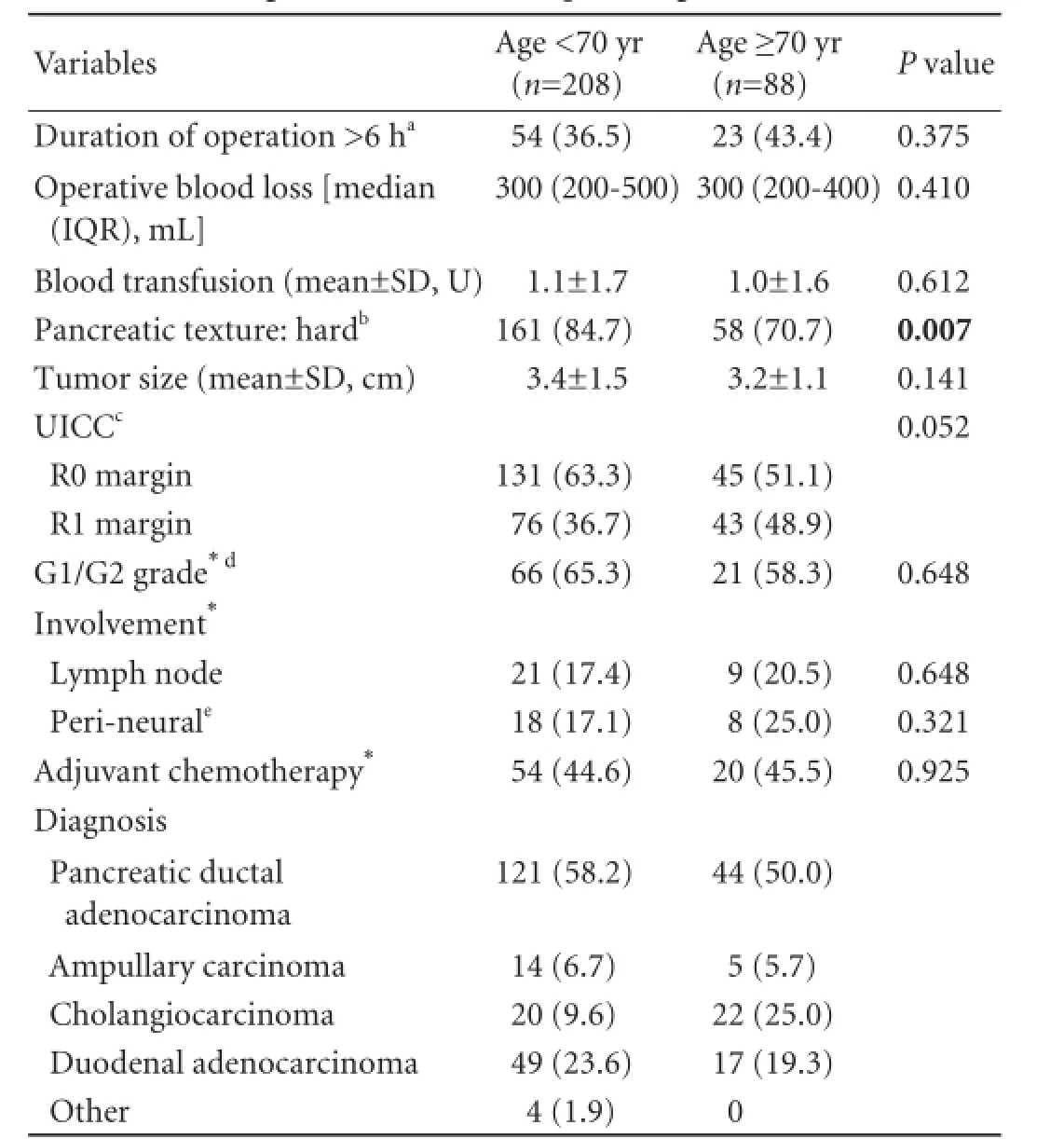

Surgical treatments and pathological results

There were no significant differences in the duration of operation, negative-margin resection, the volume of operative blood loss, and the number of packed red blood cell units. A higher proportion of patients who had hard pancreases were observed in the younger group. In the entire cohort, the most common pathology type was pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (165 patients, 55.7%). Among the 165 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the patients of the two groups had similar tumor grade, lymph node involvement, and perineural involvement. Postoperative adjuvant therapy was equally administered to the two groups (Table 2).

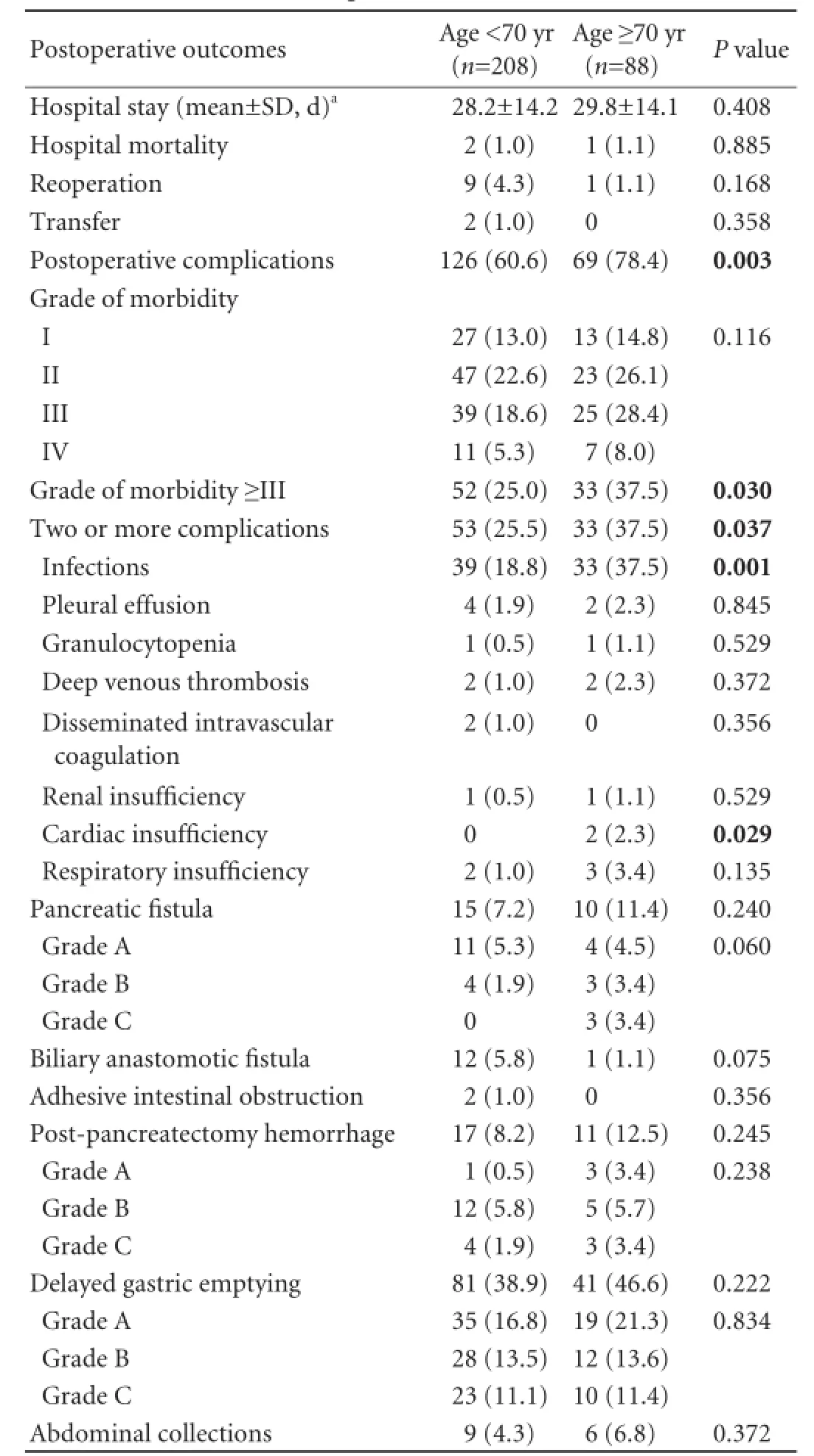

Postoperative outcomes

Two of in-hospital deaths were due to intraabdominal hemorrhage and one was due to liver abscess.There was no significant difference in the mortality rates and the reoperation and transfer rates between the two groups (allP>0.05). The mean hospital stay was 28.7±14.1 days. The hospital stay in the elder group (29.8±14.1 days) was not significantly different from that of patients in the younger group (28.2±14.2 days;P=0.408). Altogether, 195 patients (65.9%) developed at least one complication. However, the elderly patients were more likely to have postoperative complications (78.4% vs 60.6%;P=0.003). The incidence of two or more complications in the elder group was also higher in elder patients (37.5% vs 25.5%;P=0.037). According to the Clavien's classification, it was not correlated to the grade of complication. There were more patients with complications above grade III in the elder group (37.5% vs 25.0%;P=0.030). Of all the detected complications, the incidences of infections (37.5% vs 18.8%;P=0.001) and cardiac insufficiency (2.3% vs 0%;P=0.029) were significantly higher in elderly patients. Although we studied the complications of pancreatic fistula, DGE, and PPH in details, we found no differences between the two groups. There was no significant difference in the occurrence of other complications (Table 3).

Table 1.Demographic and preoperative clinical data (n, %)

Table 2.Surgical treatments and pathological results (n, %)

Identification of morbidity risk factors

We evaluated the correlation between specific comorbidity and postoperative complications. In a univariate analysis, age (P=0.001), hypertension (P=0.002) and coronary artery disease (P=0.012) were significantly associated with postoperative complications. In a multivariate analysis, age (adjusted OR=2.557,P=0.015) as well as hypertension (adjusted OR=2.443,P=0.019) were noted to be significantly related (Table 4).

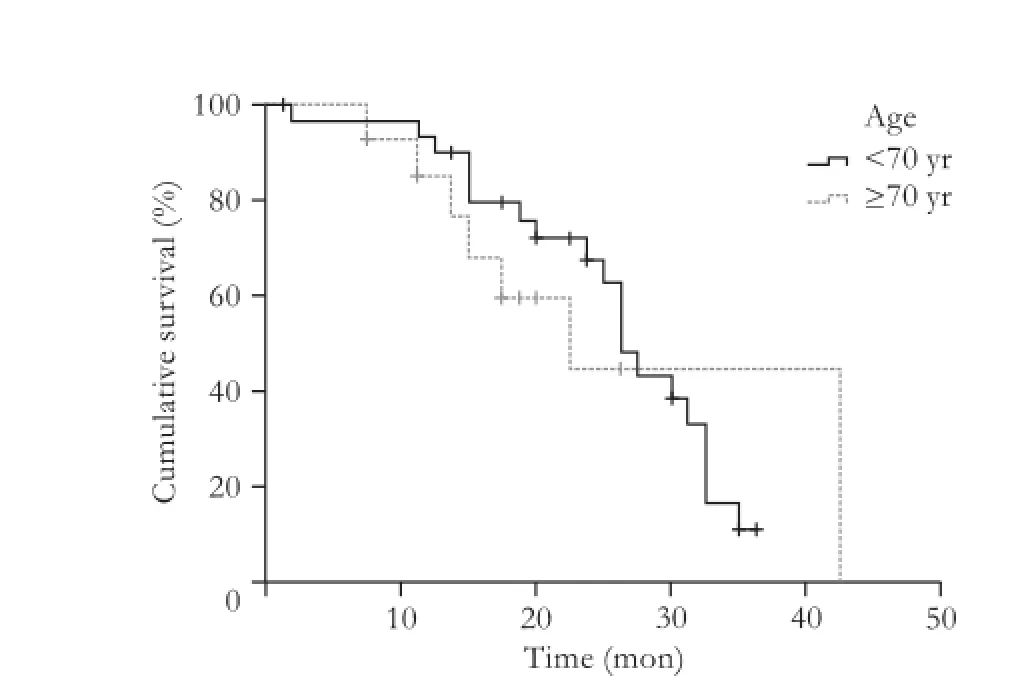

Survival

The median follow-up for all patients was 29 months. Univariate survival analysis was performed on 165 patients who were treated for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and no significant difference was found (P=0.791, Fig. 1). The median survival was 24 months (IQR, 13-31) in younger patients with the 1- and 3-year survival rates of 83.1% and 12.9%, respectively, and 29 months (IQR, 10-35) in the elderly with the 1-and 3-year survival rates of 69.1% and 0%, respectively.

Secondary analysis: the impact of age on the postoperative outcomes after PD with SMPV resection and survival analysis

We further divided the patients who underwent the PD with SMPV resection into two subgroups using the age of 70 years as a cut-off. Among the 59 patients whohad undergone vascular resection, 40 belonged to the younger group and 19 were in the elder group. The types of SMPV resections were not significantly different between the two groups. There is no difference in the postoperative complications between the types of SMPV resections (P=0.227). The histological invasion of the venous wall by cancer was found in 21 of the patients who underwent SMPV resection (35.6%). The resection margins were tumor-free (R0) in 35 patients (59.3%) and tumor-positive(R1)) in 24 patients (40.7%). The rate of R0 resection was similar to that of the whole sample (59.5%). Forty patients (67.8%) developed at least one complication. The postoperative complication rate of the SMPV resection group was similar to that of the whole sample (67.8% vs 65.9%;P=0.776). Elderly patients were more likely to have postoperative complications, but this difference was not statistically significant (84.2% vs 60.0%;P=0.063). There was one case of in-hospital death due to liver abscess. Among the preoperative clinical data, only coronary artery disease was significantly different between the two groups (36.8% vs 15.0%;P=0.049) (Table 5). There was no difference in the two groups in terms of rates of postoperative pancreatic fistula, DGE, PPH, infections, and mortality.

Table 3.Postoperative outcomes (n, %)

Table 4.Univariate and multivariate analysis for risk factors of postoperative complications

For 54 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in the PD with SMPV resection, the median survival for younger patients was 21 months versus 18 months for elderly patients (P=0.820, log-rank test) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.Cumulative survival after PD for pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma according to the age of the patient: patients <70 years old and patients ≥70 years old (P=0.791).

Table 5.The impact of age on the postoperative outcomes after PD with SMPV resection (n, %)

Fig. 2.Cumulative survival after PD for pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma according to the age of the patient in the PD combined with SMPV resection series (P=0.820).

Discussion

In our study, the elderly patients who suffered from comorbidities were more likely to have postoperative complications. Similar results were found in other studies,[12,13]which were sourced from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, whereas other prior series reported the opposite finding showing a lack of increase in postoperative complication after PD in elderly patients.[14,15]However, these retrospective cohort studies that are based on NSQIP are limited by lack of information about frequent postoperative complications such as pancreatic fistula, anastomotic leakage and DGE, which limits the ability to evaluate the effect of age on postoperative complications. Other studies[2,5]in this field were based on single-center data, which have a limited number of cases. In addition, the incidence of overall postoperativecomplication was increased in our study compared to other reports.[16,17]The increase is mainly due to our adoption of the criteria of postoperative pancreatic fistula, DGE and PPH, suggested by the ISGPS.

Multivariable analysis identified age and hypertension as independent complication risk factors. Meanwhile, we also recognized that there were more patients with complications above grade III in the elder group, which means that elderly patients are more likely to have severe complications requiring surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention or even ICU management. These offer crucial information to surgical oncologists when weighing the risks and benefits of surgery before PD. Our analysis validated that an objective cardiac assessment is paramount in guiding decision-making, especially in elderly patients. Sufficient preoperative assessment and preparation and proper postoperative treatment are essential for the recovery of elderly patients, which can efficiently help to control or reduce complications, and, therefore, reduce mortality.

Previous studies[2,5,18,19]reported that the median survival of the elderly after PD for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma ranged from 16 to 30 months. In our study, the median survival in the elderly was 29 months, which is consistent with the reported. Because of our limited experience in comprehensive treatment, the 3-year survival rate of our patients in this study is lower than that reported previously.[2,19,20]However, all of the findings support the conclusion that age is not associated with the survival rate after PD and elderly patients may have the same benefits as younger patients.[2,5,12,18,21]

We investigated the outcomes of elderly patients who had undergone PD and the outcomes of those who had undergone PD with SMPV resection. Vascular invasion has been a conventional contraindication to pancreatic resection. A study[22]demonstrated 30-day postoperative complications and an increased mortality after PD with vascular resection when compared with PD alone. On the contrary, most studies[23-25]showed that PD with SMPV resection and reconstruction, which allows complete resection, did not increase the rate of postoperative complications compared with PD alone. This conclusion was confirmed in our study. Furthermore, recent studies[3,4]argued that SMPV resection and reconstruction, if patients meet indications and are properly selected, is beneficial for long-term outcomes. In our series undergoing PD with SMPV resection, age is not associated with the increased rate of postoperative complications and survival. In high-volume centers, therefore, it is recommended that PD with SMPV resection and reconstruction should not be excluded according to patients' age. Because of the sample size in this series, however, the conclusion drawn from this analysis needs further verification in a larger sample size study.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first of this kind in China on the impact of age on the outcomes of the patients after PD and PD with SMPV resection. This investigation includes the greatest number of patients who have had SMPV resections. Because of the limited number of elderly patients, however, we try to interpret these results from a dialectical perspective to diminish the probable influence of selection bias. Moreover, the data only from a single high-volume center may not reflect the objective and comprehensive influence of age.

In conclusion, the outcomes of PD and PD with SMPV resection are helpful to surgeons facing the dilemma created by increased preoperative comorbidity and postoperative complications in elderly patients. This study would not encourage clinicians to treat elderly patients by PD or PD with SMPV resection, particularly those with cancer. Rich experience and advanced perioperative management are required to reduce or control postoperative complications in elderly patients.

Contributors:RH and HJH proposed the study and revised the article. SJW performed research and wrote the first draft. ZPP collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. HJH is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Delcore R, Thomas JH, Hermreck AS. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for malignant pancreatic and periampullary neoplasms in elderly patients. Am J Surg 1991;162:532-536.

2 Scurtu R, Bachellier P, Oussoultzoglou E, Rosso E, Maroni R, Jaeck D. Outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer in elderly patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:813-822.

3 Chen Y, Hao J, Ma W, Tang Y, Gao C, Hao X. Improvement in treatment and outcome of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in north China. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:1026-1034.

4 Bachellier P, Nakano H, Oussoultzoglou PD, Weber JC, Boudjema K, Wolf PD, et al. Is pancreaticoduodenectomy with mesentericoportal venous resection safe and worthwhile? Am J Surg 2001;182:120-129.

5 Kang CM, Kim JY, Choi GH, Kim KS, Choi JS, Lee WJ, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in the elderly. Yonsei Med J 2007;48:488-494.

6 Richter A, Niedergethmann M, Lorenz D, Sturm JW, Trede M, Post S. Resection for cancers of the pancreatic head inpatients aged 70 years or over. Eur J Surg 2002;168:339-344.

7 Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40: 373-383.

8 Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-213.

9 Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005;138:8-13.

10 Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2007;142: 761-768.

11 Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery 2007;142:20-25.

12 Khan S, Sclabas G, Lombardo KR, Sarr MG, Nagorney D, Kendrick ML, et al. Pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma in the very elderly; is it safe and justified? J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1826-1831.

13 Haigh PI, Bilimoria KY, DiFronzo LA. Early postoperative outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy in the elderly. Arch Surg 2011;146:715-723.

14 de la Fuente SG, Bennett KM, Pappas TN, Scarborough JE. Pre- and intraoperative variables affecting early outcomes in elderly patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:887-892.

15 Suc B, Msika S, Piccinini M, Fourtanier G, Hay JM, Flamant Y, et al. Octreotide in the prevention of intra-abdominal complications following elective pancreatic resection: a prospective, multicenter randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg 2004;139:288-295.

16 Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sohn TA, Campbell KA, Sauter PK, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without distal gastrectomy and extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma, part 2: randomized controlled trial evaluating survival, morbidity, and mortality. Ann Surg 2002;236:355-368.

17 Tani M, Kawai M, Hirono S, Ina S, Miyazawa M, Nishioka R, et al. A pancreaticoduodenectomy is acceptable for periampullary tumors in the elderly, even in patients over 80 years of age. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009;16:675-680.

18 Chen JW, Shyr YM, Su CH, Wu CW, Lui WY. Is pancreaticoduodenectomy justified for septuagenarians and octogenarians? Hepatogastroenterology 2003;50:1661-1664.

19 Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Arnold MA, Chang DC, Coleman J, et al. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: A single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1199-1211.

20 Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Fortner JG, Brennan MF. Pancreatic or liver resection for malignancy is safe and effective for the elderly. Ann Surg 1995;222:426-437.

21 Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, et al. Should pancreaticoduodenectomy be performed in octogenarians? J Gastrointest Surg 1998;2:207-216.

22 Castleberry AW, White RR, De La Fuente SG, Clary BM, Blazer DG 3rd, McCann RL, et al. The impact of vascular resection on early postoperative outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: an analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:4068-4077.

23 Fuhrman GM, Leach SD, Staley CA, Cusack JC, Charnsangavej C, Cleary KR, et al. Rationale for en bloc vein resection in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma adherent to the superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence. Pancreatic Tumor Study Group. Ann Surg 1996;223:154-162.

24 Chua TC, Saxena A. Extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection for pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1442-1452.

25 Zhou GW, Wu WD, Xiao WD, Li HW, Peng CH. Pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric-portal vein resection: report of 32 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2005;4:130-134.

Received March 20, 2013

Accepted after revision November 10, 2013

Author Affiliations: Departments of Pancreatic Cancer (Sun JW, Ren H and Hao JH) and Thoracic Oncology (Zhang PP), Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital, Tianjin 300060, China

Ji-Hui Hao, PhD, Department of Pancreatic Cancer, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital, Tianjin 300060, China (Tel/Fax: +86-22-23340123; Email: jihuihao@yahoo.com)

© 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60046-1

Published online March 27, 2014.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Prostacyclin decreases splanchnic vascular contractility in cirrhotic rats

- A modified protocol with rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin in emergent ABO-incompatible liver transplantation for acute liver failure

- Ultrasonic integrated backscatter in assessing liver steatosis before and after liver transplantation

- Liver transplantation using organs from deceased organ donors: a single organ transplant center experience

- A matched-pair analysis of laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: oncological outcomes using Leeds Pathology Protocol

- Effects of melatonin on the oxidative damage and pancreatic antioxidant defenses in ceruleininduced acute pancreatitis in rats