Acute liver failure in Chinese children: a multicenter investigation

2014-05-04PanZhaoChunYaWangWeiWeiLiuXiWangLiMingYuandYanRongSun

Pan Zhao, Chun-Ya Wang, Wei-Wei Liu, Xi Wang, Li-Ming Yu and Yan-Rong Sun

Beijing, China

Acute liver failure in Chinese children: a multicenter investigation

Pan Zhao, Chun-Ya Wang, Wei-Wei Liu, Xi Wang, Li-Ming Yu and Yan-Rong Sun

Beijing, China

BACKGROUND:Currently, no documentation is available regarding Chinese children with acute liver failure (ALF). This study was undertaken to investigate etiologies and outcomes of Chinese children with ALF.

METHODS:We retrospectively enrolled 32 pediatric patients with ALF admitted in five hospitals in different areas of China from January 2007 to December 2012. The coagulation indices, serum creatinine, serum lactate dehydrogenase, blood ammonia and prothrombin activity were analyzed; the relationship between these indices and mortality was evaluated by multivariate analysis.

RESULTS:The most common causes of Chinese children with ALF were indeterminate etiology (15/32), drug toxicity (8/32), and acute cytomegalovirus hepatitis (6/32). Only 1 patient (3.13%) received liver transplantation and the spontaneous mortality of Chinese children with ALF was 58.06% (18/31). Patients who eventually died had higher baseline levels of international normalized ratio (P=0.01), serum creatinine (P=0.04), serum lactate dehydrogenase (P=0.01), blood ammonia (P<0.01) and lower prothrombin activity (P=0.01) than those who survived. Multivariate analysis showed that the entry blood ammonia was the only independent factor significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio=1.069, 95% confidence interval 1.023-1.117,P<0.01) and it had a sensitivity of 94.74%, a specificity of 84.62% and an accuracy of 90.63% for predicting the death. Based on the established model, with an increase of blood ammonia level, the risk of mortality would increase by 6.9%.

CONCLUSIONS:The indeterminate causes predominated in the etiologies of ALF in Chinese children. The spontaneous mortality of pediatric patients with ALF was high, whereas the proportion of patients undergoing liver transplantation was significantly low. Entry blood ammonia was a reliable predictor for the death of pediatric patients with ALF.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:276-280)

acute liver failure;

children;

etiology;

mortality;

prognosis

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare but lifethreatening syndrome. Although definitions of ALF in adults include the presence of hepatic encephalopathy (HE), HE in younger children is difficult to assess. Hence it may not be essential to the diagnosis of ALF in children.[1]Additionally, the etiologic spectrum and the clinical features of pediatric patients with ALF differ from those of adults with ALF.[2,3]It is very necessary to do studies in children with ALF.

The etiologies of pediatric patients with ALF showed worldwide variations. In the United States, most cases are indeterminate,[1]but viral infections are the leading cause in India.[4]In China, the national diagnostic and treatment guidelines for liver failure were issued by theChinese Society of Hepatologyin late 2006.[5]From then on, the diagnosis of ALF was standardized. As this result, we enrolled pediatric patients with ALF from January 2007. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a multicenter study on Chinese pediatric patients with ALF.

Methods

Patient collection

ALF in pediatric patients in the present study was defined by coagulopathy [prothrombin activity (PTA)≤40% or international normalized ratio (INR)≥1.5, excluding hematologic diseases] and jaundice [serum total bilirubin (TBil)≥171 μmol/L] within 4 weeks in a child without pre-existing liver diseases. Patients (≤12 years old) with ALF from January 2007 to December 2012 were included in this study.

To ensure the representativeness and comparability of the data, we selected five tertiary military hospitals in different areas of China: Beijing 302 Hospital, General Hospital of the PLA, Changhai Hospital, General Hospital of Jinan Military Region and General Hospital of Lanzhou Military Region.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of each hospital. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians.

Data extraction and assessment

The following variables were obtained from the electronic medical records and follow-up documents: causes, outcomes (death, survival, transplantation), gender, age, body mass index (BMI), white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin, platelet count, PTA, INR, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), cholinesterase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), TBil, albumin, creatinine, urea nitrogen, glucose, Na+, K+, Cland blood ammonia (BLA).

The etiology of ALF in the pediatric patients was ascertained by historical review and clinical, radiographic and laboratory evaluations. It was considered indeterminate when the evaluations failed to indicate a specific cause.

Statistical analysis

Results

Causes, mortality and transplantation

Thirty-two children with ALF were finally included in this study. Of them, 15 (46.88%) had indeterminate cause, 8 (25.00%) had drug toxicity, 6 (18.75%) had acute cytomegalovirus (CMV) hepatitis, 2 (6.25%) had Wilson's disease, and 1 (3.13%) had malignant extrahepatic metastasis.

In the drug-related cases, 3 were due to acetaminophen, 2 were attributed to herbal remedies, 2 were caused by antibiotics, and 1 was due to antiallergic drug.

Only one patient received liver transplantation in this study, but died eventually. In the other 31 patients without liver transplantation, 13 (41.94%) survived and 18 (58.06%) died. The causes and outcomes of children with ALF are shown in Fig. 1.

Baseline characteristics on admission

Table summarizes the clinical characteristics of the pediatric patients with ALF on admission according to the outcomes (death or survival). The median levels of INR (P=0.01), serum creatinine (P=0.04), serum LDH (P=0.01) and BLA (P<0.01) in non-surviors were significantly higher than those in survivors, andthe median PTA (P=0.01) in the non-survivors were notably lower than those in the survivors. No statistical difference was found in other variables.

Fig. 1.Etiologies and outcomes of 32 pediatric patients with acute liver failure in China. Indeterminate etiology, drug toxicity and acute cytomegalovirus hepatitis were the most common causes of pediatric acute liver failure.

Table.Baseline characteristics of children with acute liver failure on admission and comparison of variables between patients who died and survived

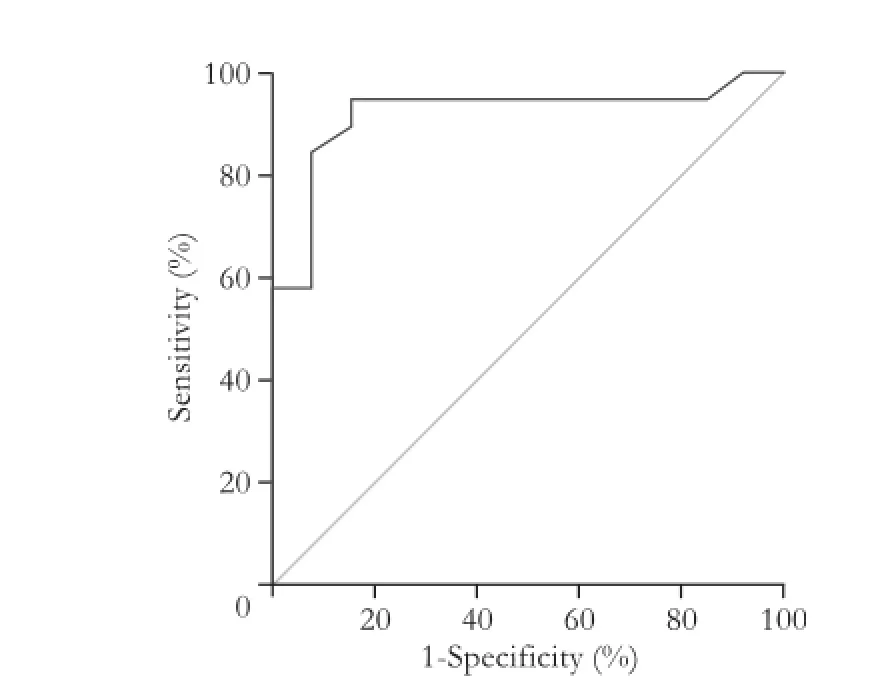

Fig. 2.Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for the established prediction model.

Outcomes of pediatric patients with ALF

Multivariate analysis revealed that entry BLA was the solely factor for predicting the mortality of pediatric patients with ALF [odds ratio=1.069, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.023-1.117,P<0.01]. With an increase of BLA level, the risk of mortality would increase by 6.9%. Using a threshold value of 0.3887, this established model (BLA level ≥76 μmol/L) had a sensitivity of 94.74%, a specificity of 84.62%, and an accuracy of 90.63%. ROC curve analysis was made for predictive power of BLA (the area under the ROC curve 0.9190, 95% CI 0.8120-1.0000) (Fig. 2). The relationship between the estimated probability of death in pediatric patients with ALF and the levels of BLA is shown in Fig. 3.

苏东坡既不追随王安石,也不追随司马光,始终坚持自己的政治见解,这也使他的政治生涯十分坎坷。“时宜”是指当时的社会风气和潮流,“合时宜”就是随波逐流、趋炎附势,“不合时宜”就是不曲意逢迎。苏轼的“不合时宜”,反映出他孤傲的气节、耿直的性情。

Fig. 3.Relationship between the estimated probability of death in pediatric patients with acute liver failure and levels of blood ammonia.

Discussion

The causes of ALF in children vary with demographic and geographic locations.[6]A report from Thailand demonstrated that dengue virus infection is a major cause of ALF in Thai children.[7]Another report showed that the most frequent etiology for ALF among pediatric Filipinos is hepatitis A virus.[8]In our study, indeterminate cause predominated in the etiologies of ALF in Chinese children. Acute hepatitis B was found not to be the common cause in our study. This finding was not consistent with that of a previous study,[9]in which acute hepatitis B was the leading cause for ALF in children. The difference could be due to the extensive hepatitis B immunization,[10]which has significantly reduced the incidence of hepatitis B virus infection in China.

CMV hepatitis is relatively common in young children, especially in early infancy.[11]The clinical spectrum of CMV infection in children varies from an asymptomatic infection or a mild disease to severe systemic involvement.[12]Squires et al[13]reported in 2006 that the incidence of ALF in children causedby acute CMV infection was 1/348. In our study, the incidence was higher than 1/348, which might be a reflection of the increasing awareness of Chinese physicians on CMV hepatitis in China. The average age of these patients with acute CMV infection were much younger than that of patients with other etiologies in our study.

The death of pediatric patients with ALF was reported to be nearly 50%.[1]In our study, the mortality of ALF without liver transplantation was 58.06%. Liver transplantation remained the only treatment option for ALF when standard medical therapy failed.[14]Our study revealed that although liver transplantation was available in the investigated hospitals, the rate of transplantation was as low as 3.13%. This result was due to difficulties in obtaining organs in emergency conditions. Hence, it was critically important to determine the prognosis of pediatric patients with ALF as early as possible. To ensure the timeliness and practicality of the forecasting model,[15]we used entry variables rather than peak ones to predict the outcomes of pediatric patients with ALF because it was late to make critical decisions when the peak values had been reached.

In the prognostic model of ALF, BLA was taken as an independent predictor for the death. This result was consistent with that reported by Chan et al.[9]Previous studies[16-19]showed that BLA was a reliable predictor for the death of adult ALF. In an Indian study on pediatric patients with ALF, TBil on admission was associated with the increased risk of mortality;[4]however, in this study, TBil was not included in the prognostic model. The discrepancy was due to the set bottom line of serum TBil (ten times higher than the normal value) as a mandatory diagnostic element. As a result, patients who satisfied with the required standard all had a high level of serum TBil. Moreover, the median level of entry serum TBil in survivors was similar to that in nonsurvivors.

The limitation of the present study was the small number of the cases because of the rarity of ALF in children, which might somewhat lead to inadequate test power of the logistic regression.

In conclusion, indeterminate causes predominated in the etiologies of Chinese children with ALF. In China, the spontaneous mortality of pediatric patients with ALF was high, whereas the rate of liver transplantation was significantly low. BLA on admission was a reliable predictor for the death of children with ALF.

Contributors:ZP designed the study. ZP and WCY collected, and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. ZP and LWW performed the statistical analysis of the data. WX, YLM and SYR provided the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ZP is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:The study was approved by the ethics committees of each hospital. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or guardians for being included in the study.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Lu BR, Gralla J, Liu E, Dobyns EL, Narkewicz MR, Sokol RJ. Evaluation of a scoring system for assessing prognosis in pediatric acute liver failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:1140-1145.

2 Devictor D, Tissieres P, Durand P, Chevret L, Debray D. Acute liver failure in neonates, infants and children. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;5:717-729.

3 Bretherick AD, Craig DG, Masterton G, Bates C, Davidson J, Martin K, et al. Acute liver failure in Scotland between 1992 and 2009; incidence, aetiology and outcome. QJM 2011;104: 945-956.

4 Kaur S, Kumar P, Kumar V, Sarin SK, Kumar A. Etiology and prognostic factors of acute liver failure in children. Indian Pediatr 2013;50:677-679.

5 Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases and Parasitology, Severe Liver Diseases and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Hepatology. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for liver failure. J Clin Hepatol (Chinese) 2006;9:321-324.

6 Dhawan A. Etiology and prognosis of acute liver failure in children. Liver Transpl 2008;14:S80-84.

7 Poovorawan Y, Hutagalung Y, Chongsrisawat V, Boudville I, Bock HL. Dengue virus infection: a major cause of acute hepatic failure in Thai children. Ann Trop Paediatr 2006;26: 17-23.

8 Bravo LC, Gregorio GV, ShafiF, Bock HL, Boudville I, Liu Y, et al. Etiology, incidence and outcomes of acute hepatic failure in 0-18 year old Filipino children. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2012;43:764-772.

9 Chan PC, Chen HL, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Chang LY, Lee PI, et al. Outcome predictors of fulminant hepatic failure in children. J Formos Med Assoc 2004;103:432-436.

10 Lu SQ, McGhee SM, Xie X, Cheng J, Fielding R. Economic evaluation of universal newborn hepatitis B vaccination in China. Vaccine 2013;31:1864-1869.

11 Hu Y, Chen L, Shu J, Yao Y, Yan HM. Clinical study on treatment of infantile cytomegalovirus hepatitis with integrated Chinese and Western medicine. Chin J Integr Med 2012;18:100-105.

12 Varani S, Landini MP. Cytomegalovirus-induced immunopathology and its clinical consequences. Herpesviridae 2011;2:6.

13 Squires RH Jr, Shneider BL, Bucuvalas J, Alonso E, Sokol RJ, Narkewicz MR, et al. Acute liver failure in children: the first 348 patients in the pediatric acute liver failure study group. J Pediatr 2006;148:652-658.

14 Singhal A, Vadlamudi S, Stokes K, Cassidy FP, Corn A,Shrago SS, et al. Liver histology as predictor of outcome in patients with acute liver failure. Transpl Int 2012;25:658-662.

15 Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, van der Windt DA, Hayden JA, Perel P, Schroter S, et al. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 3: prognostic model research. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001381.

16 Rutherford A, King LY, Hynan LS, Vedvyas C, Lin W, Lee WM, et al. Development of an accurate index for predicting outcomes of patients with acute liver failure. Gastroenterology 2012;143:1237-1243.

17 Du WB, Pan XP, Li LJ. Prognostic models for acute liver failure. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010;9:122-128.

18 Garcin JM, Bronstein JA, Cremades S, Courbin P, Cointet F. Acute liver failure is frequent during heat stroke. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:158-159.

19 Sugawara K, Nakayama N, Mochida S. Acute liver failure in Japan: definition, classification, and prediction of the outcome. J Gastroenterol 2012;47:849-861.

Received July 3, 2013

Accepted after revision November 4, 2013

Author Affiliations: Liver Failure Therapy and Research Center, Beijing 302 Hospital (PLA 302 Hospital), Beijing 100039, China (Zhao P); Emergency Department, Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100029, China; Intensive Care Unit, Emergency Department, General Hospital of PLA, Beijing 100853, China (Wang CY); Postgraduate Division, Academy of Military Medical Science, Beijing 100850, China (Liu WW); Medical Administration Department, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai 200433, China (Wang X); Medical Administration Department, General Hospital of Jinan Military Region, Jinan 250000, China (Yu LM); Medical Administration Department, General Hospital of Lanzhou Military Region, Lanzhou 730050, China (Sun YR)

Pan Zhao, MD, Liver Failure Therapy and Research Center, Beijing 302 Hospital (PLA 302 Hospital), No. 100 of West Fourth Ring Middle Road, Beijing 100039, China (Tel/Fax: 86-10-66933020; Email: doczhaopan@126.com)

© 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60041-2

Published online March 27, 2014.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Emergency cholecystectomy vs percutaneous cholecystostomy plus delayed cholecystectomy for patients with acute cholecystitis

- Ron receptor-dependent gene regulation of Kupffer cells during endotoxemia

- HepG2 cells recovered from apoptosis show altered drug responses and invasiveness

- Detection of liver micrometastases from colorectal origin by perfusion CT in a rat model

- Sodium butyrate protects against toxin-induced acute liver failure in rats

- PossibIe benefit of spIenectomy in Iiver transpIantation for autoimmune hepatitis