Thirty Years of English Fever

2014-02-24byYeBiao

by+Ye+Biao

“Was last nights Eng- lish program one of yours?” queried Zhang Xiangshan, then director of the Central Broadcasting Bureau under todays State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, upon entering the office of the Education Department at China Central Television (CCTV) on January 6, 1982.

No one in the room understood the question including the programs director Xu Xiongxiong. At 6:20 p.m. the day before, Follow Me, an English learning program, aired on CCTV 1.

“Its based on a BBC show,” muttered Xu.

“I watched it,” continued Zhang, “Very good!” and then, he left.

Nobody expected that to be a tipping point for China. China Daily later reported that the program attracted more than 10 million viewers, which made for impressive ratings at the time.

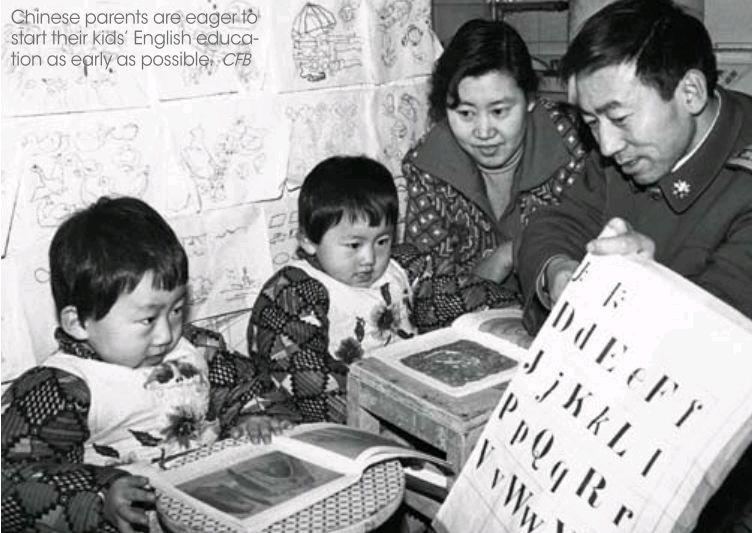

Over the following years, people throughout China became obsessed with learning English, and the fever only intensified after the countrys implementation of economic reform and opening-up policies in the late 1970s meant more people left to study abroad.

“Some Gin?”

Katherine Flower arrived in Beijing in September 1981. The London red-head named herself Hua (“flower” in Chinese) Kelin.

The year 1978 brought Chinas resumption of selecting candidates to study abroad. That year, the Chinese government financed the studies of 480 students in 41 countries. The door of communication only became wider once it cracked open. By 1985, the country had financed the foreign studies of 20,000 people. In 1981, the State Council issued rules which allowed self-financed students to matriculate abroad, triggering an even bigger wave of overseas study. The count of students taking the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) rose from 285 in 1981 to 18,000 in 1986.

In 1981, Hu Wenzhong, a member of one of the first groups of students to go abroad with financial support from the government, returned to China and became deputy director of Beijing Foreign Studies University. Xu Xiongxiong, his former classmate, saw a promo for Follow Me during a visit to the BBC. Xu called Hu Wenzhong and invited Katherine Flower to co-produce a Chinese version of the show.

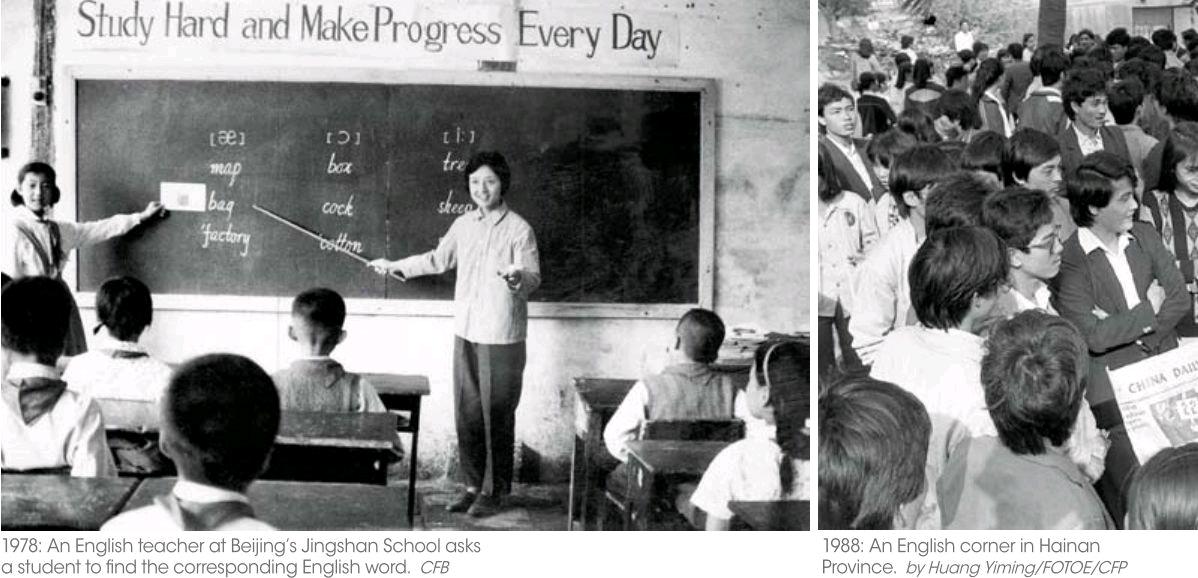

By the time Follow Me hit the air waves, China had opened 29 counties and cities to foreign tourists, which increased demand for translators to work in economics, culture, science, and technology. Learning English became en vogue across the country. In 1984, English became one of the major sections of the national college entrance examination. In 1986, it became part of assessments for professional titles.

Along with its language-learning influence, Follow Me also served as a window for Chinese people to learn about Western lifestyles. During a stay in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Flower was greeted by hotel staff in English with,“Hello! Want some gin?” and handed a cup of tea. There was, of course, nothing close to gin at the hotel; and the attendant was simply repeating English she had learned on Follow Me.

“Cheap Foreign Labor”

In the early 1990s, ten years after Follow Me first aired, Katherine Flower returned to China, where she was still a recognizable celebrity. However, everything else was totally different.

In the late 1980s, China began testing English in college. In 1990, Beijing hosted the Asian Games, its first international sporting event since the founding of New China in 1949, which sparked another wave of English learning.

Unprecedentedly, the whole country watched the Asian Games on the same TV channel. English learning penetrated greater numbers of peoples lives as early as 1985 when the government loosened restrictions on visiting relatives abroad, giving rise to non-governmental English teaching institutes such as New Oriental.

Chinese people found wide-ranging views of the Western world. Chen Danqing, a well-known Chinese painter, recalled his first visit to the United States in 1982. “We thought we could communicate with the West,” he recalls, “but found that they didnt want to talk unless we spoke their language, and we were not fully prepared.”

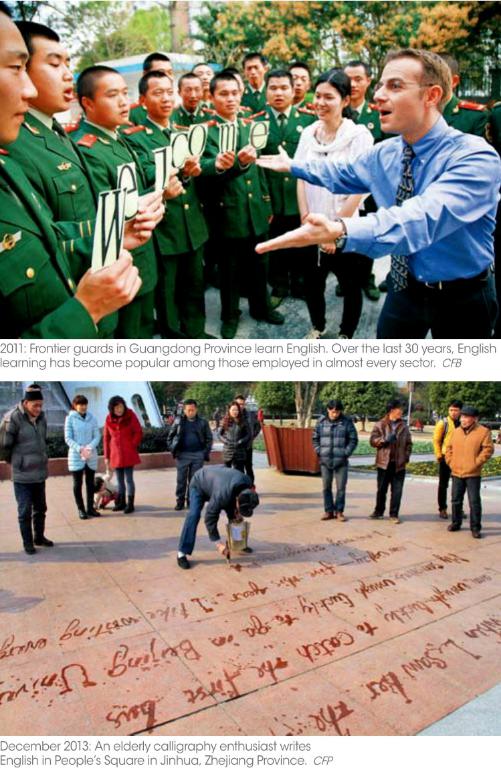

Still, English has only seen growing popularity. Some voices, such as Li Yang, took the lead and called for learners to speak English as loudly as possible.

“Never let your country down! I can make it!” Li instructed his students to shout while out on a morning jog in Crazy English, a documentary directed by Zhang Yuan in 1998. He then patted a foreign English teacher on the shoulder. “We should use cheap foreign labor, right?” he joked.

Fever to Anxiety

During her visit to China in 2008, Singaporean film director Lian Pek found Chinese people still yearning to learn English, but looking at the language with a new attitude.

In 2006, Follow Me was resurrected by Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, with assistance of Katherine Flower and Yang Lan, a Chinese journalist, talk show host, and English enthusiast. However, the landscape wasnt as favorable as before. Soon after the launch of the new Follow Me, San Diego-based Global Lan-guage Monitor reported that English was experiencing unprecedented reform due to mistakes made by non-native English speakers – some 250 million in China.

Formerly a journalist and a host on CNN and BBC, Lian Pek was deeply impressed by the growing number of English speakers in China when she visited. The popularity of English reached its apex in 2008 when Beijing hosted the Olympic Games. To mark the event, she decided to make a documentary to capture those who were enthusiastic about English and eager to share the countrys prosperity with the rest of the world via the Olympics.

Waning curiosity about Englishspeaking countries and communication setbacks cooled down English in China as the country gained growing national power.“I speak English for the sake of its native speakers who cant speak any Chinese,”grinned some.

Its no longer a big deal for Chinese students to go abroad. Statistics from the Ministry of Education in 2009 revealed that of the 8.34 million high-school graduates 200,000 chose to study abroad.

When it comes to “English fever” in countries across East Asia, Zhou Ning, president of the College of Humanities under Xiamen University, believes that despite these countries long history and profound cultures, they are eager to learn English to accelerate their modernization after being shocked by advanced Western culture. However, now theyre stuck in purgatory between English and maintaining their native tongue as they adjust to the absorption of Western culture.