白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠的巢址特征

2013-12-09李艳红关进科黎大勇

李艳红,关进科,黎大勇,胡 杰

(西南野生动植物资源保护教育部重点实验室,西华师范大学珍稀动植物研究所, 南充 637009)

白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠的巢址特征

李艳红,关进科,黎大勇,胡 杰*

(西南野生动植物资源保护教育部重点实验室,西华师范大学珍稀动植物研究所, 南充 637009)

动物的巢为其育幼、避敌和休息等提供了适宜的空间,因此,了解其巢址特征对于物种的保护和管理有着重要的意义。灰头小鼯鼠是一种小型树栖、夜行性哺乳动物,在国内主要分布在中部、南部及西南地区。2012年4月至6月和2012年9月至12月在白马雪山国家级自然保护区对灰头小鼯鼠的巢址特征进行了初步研究。结果表明:灰头小鼯鼠共利用2种巢,在针叶树上,灰头小鼯鼠多利用树枝巢;在阔叶树上,灰头小鼯鼠仅利用树洞巢。巢多紧靠树干(0.2±0.1) m,平均巢高(11.3±0.8) m,巢口无方向偏好。灰头小鼯鼠喜欢选择冠幅更大、通道数更多的树上筑巢,此外,其对郁闭度大,灌木盖度高的生境有明显的选择性。

灰头小鼯鼠;巢址;白马雪山自然保护区

灰头小鼯鼠(Petauristacaniceps)是一种小型树栖、夜行性哺乳动物,在国外主要分布于尼泊尔、印度、孟加拉国、不丹和锡金[1],在国内主要分布在四川、陕西、贵州和西藏等省[2]。

动物的巢为其育幼、躲避敌害、休息和保持体温等提供了适宜的空间[3- 4]。合适的巢址是树栖动物最重要的栖息地[5- 6]。鼯鼠一般利用两种巢穴,一种是以树的空腔为巢,称为树洞巢;另一种是在树枝上筑巢,称为树枝巢[7- 8]。目前,国外对鼯鼠巢址的研究多集中在北方飞鼠(Glaucomyssabrinus)[9- 12]、南方飞鼠(Glaucomysvolans)[13]、西伯利亚飞鼠(Pteromysvolansorii)[14]等物种,而国内的相关研究则甚为缺乏。鉴于此,于2012年4—6月和9—12月从巢位、巢树及巢址3个尺度对云南白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠的巢址特征进行了初步的定量研究,目的在于揭示影响灰头小鼯鼠巢址选择的主要生态因子,以期进一步丰富灰头小鼯鼠野生种群的生态生物学资料。

1 研究地概况

白马雪山国家级自然保护区位于滇西北横断山脉腹地,地理位置为27°36′N,99°18′E、27°26′N,99°11′E,主要保护对象为滇金丝猴及其栖息的暗针叶林生态环境。研究区域(塔城、攀天阁)内主要的地貌为中、高山,海拔2400—4000 m。区内季风气候突出、干湿季分明, 年平均气温14.5 ℃(海拔2448 m处)。区内主要的森林植被类型有5种:(1)暖针叶林,分布在海拔2400—3100 m之间,主要树种为云南松(pinusyunnanensis);(2)常绿阔叶林,分布在海拔2400—3000 m 之间, 主要树种为青冈栎属的种类(Cyclobalanopsisspp.);(3)针阔混交林,分布在海拔2600—3400 m,主要树种为糙皮桦(Betulautilis)、花楸(Sorbusspp.)、云南铁杉(Tsugadumosa)等;(4)山地硬叶阔叶林,分布在海拔3200—3500 m, 主要的树种为黄背栎(Quercuspannosa);(5)暗针叶林,分布在海拔3400—4000 m, 主要的树种包括云杉(Picespp.)、冷杉(Abiesspp.)和垂枝香柏(Sabinapingii)等[15]。

2 研究方法

2.1 野外调查

2.1.1 样方设置

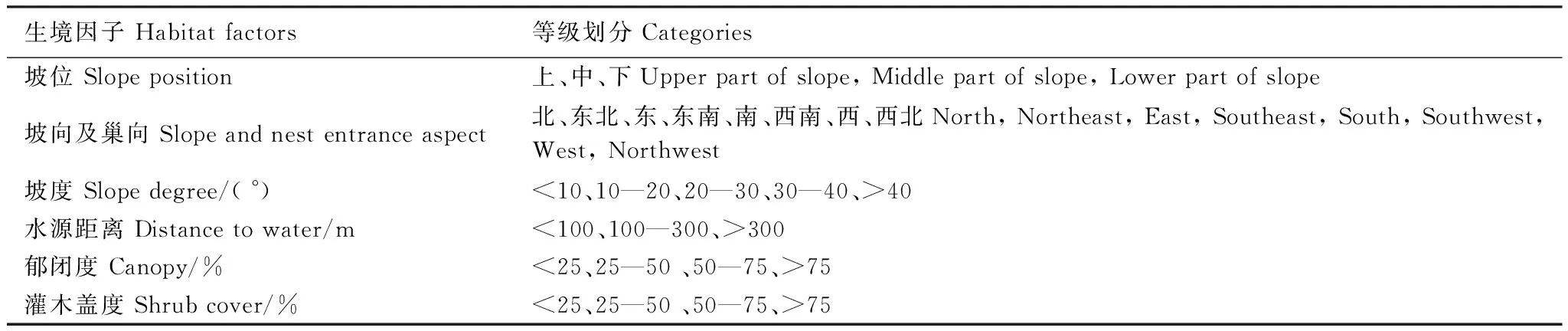

在各种森林植被类型中进行调查,当发现灰头小鼯鼠的巢(包括树枝巢和树洞巢)址后,即用全球定位仪(GAMIN72 GPS)进行定位,以巢树为中心做一个20 m×20 m的巢址生境样方。主要测量和记录海拔、坡向、坡位、坡度、水源距离、郁蔽度、植被类型、乔木高度、乔木胸径、乔木密度(样方内DBHgt;10 cm的乔木数)和灌木盖度,共11个参数。其中,乔木高度、第一主枝高、巢高等通过测距仪(奥卡800VR)进行测量;乔木胸径用皮尺测量;巢的大小用卷尺测量;海拔利用GPS进行测定;巢向和坡向用指南针测定;其他因子主要采用目测估计。生境因子的等级划分见表1。

表1 灰头小鼯鼠部分生境因子的划分等级

对照生境样方的选取参照温知新等[16]的方法。即以巢树为中心,从预先准备好的、分别写有北、东北、东、东南、南、西南、西、西北8个方位的纸条中,随机抽取一张,然后按照纸条所给出的方向行走50 m,选择一棵与巢树高度和胸径相近的乔木树(对照树)作为对照样方的中心。对照样方的面积大小和记录参数与巢址样方一致。

2.1.2 巢及巢树相关因子收集

共测量和记录了巢的类型(树枝巢和树洞巢)、巢高(巢与地面的距离)、巢口大小(巢口直径)、巢深(巢口至巢底的高度)、巢向、巢离主干距离6个与巢相关的因子,以及巢树(或对照树)的树种、胸径、树高、第一主枝(活枝) 高、冠幅、通道数(通道是指树枝与巢树或对照树间距0.5 m以内,胸径gt;10 cm的树[17])等6个与巢树相关的因子,并计算出相对巢高(巢高/巢树高)。此外,还对树枝巢的巢材组成进行了初步分析(为减少破坏,仅测量了6个样本)。

在实际调查过程中,发现的树洞共有21个。每发现一个树洞,就敲击树干,看到鼯鼠飞出,则记为一个树洞巢,但其中有6个树洞未见到鼯鼠飞出,不能确定是否是该种鼯鼠的巢;树枝巢在调查过程中共见到15个,因此,本研究中分别选取了15个树洞巢和15个树枝巢来进行比较分析。

2.2 数据处理

数据的处理和统计工作在SPSS17.0平台上进行。应用Mann-Whitney U检验对树枝巢与树洞巢的巢口大小和巢深进行差异性检验;采用单因素方差分析(One-Way ANOVA Test)对巢树和对照树的冠幅、通道数、树高、胸径、第一主枝高等变量,以及树枝巢和树洞巢的胸径、树高、巢高和相对巢高进行差异性检验;利用卡方检验(Chi-Square)分析灰头小鼯鼠对巢口方向是否具有选择性。由于逻辑斯蒂回归分析既适于对数值型变量的分析,也适于对分类型变量的分析[11],因此,本研究采用该方法来分析影响灰头小鼯鼠巢址选择的生态因素。各变量在描述时采用Mean ± SE表示,其中Mean为算术平均值,SE为标准误。所有检验的显著水平设定为0.05,即当Plt;0.05时为差异显著。

3 结果

3.1 巢及巢位特征

本次调查发现,灰头小鼯鼠使用的巢均位于活树上,分为两种类型:一种是树枝巢(n=15),一种是树洞巢(n=15)。树洞巢和树枝巢的巢口都略成圆形。树枝巢的巢口大小为(12.1±0.1) cm,巢深为(23.4±1.1) cm;树洞巢的巢口大小为(10.8±0.5) cm,巢深为(59.2±1.2) cm。巢口大小和巢深两个变量在树枝巢与树洞巢间均存在显著的差异(Mann-Whitney U testZ=-3.521,P=0.000;Z=-4.692,P=0.000)(表2)。

表2 白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠两种巢大小的比较

在云南松林内,树枝巢的巢材常由云南松树枝、树皮、苔藓及松毛等材料组成;在垂枝香柏林内,树枝巢的巢材常由香柏树枝、树皮和苔藓等材料组成(表3)。

表3 白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠树枝巢巢材组成

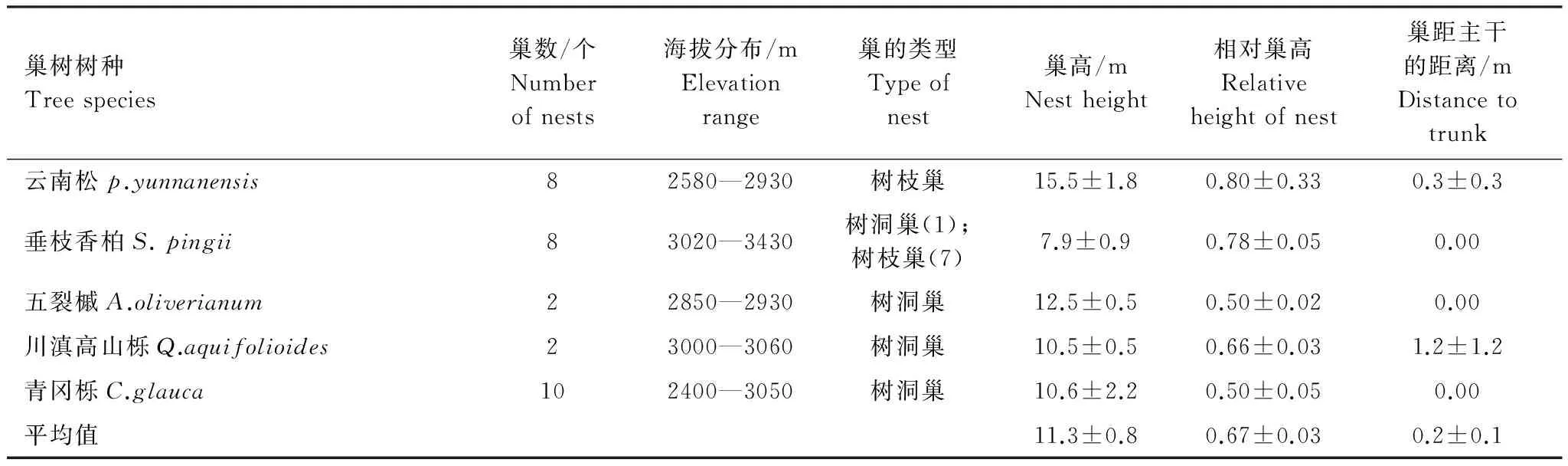

本次调查未发现同一树上有多巢共存的现象。巢分布的海拔范围在2400—3430 m之间,涉及区内除山地硬叶阔叶林以外的所有森林植被类型。巢基本都在主干上,平均距主干的距离为(0.2±0.1) m。仅在1棵川滇高山栎(Quercusaquifolioides)上发现1个树洞巢位于距主干2.3 m的侧枝上(表4)。平均巢高为(11.3±0.8) m,平均相对巢高为(0.67±0.03),说明灰头小鼯鼠一般都选择在巢树的中上部位筑巢。

灰头小鼯鼠树枝巢的巢高(12.4±1.3) m和树洞巢的巢高(10.2±0.6) m之间没有显著差异(One-Way ANOVA Test,F1,28=2.195,P=0.150),而树枝巢的相对巢高为(0.77±0.03),树洞巢的为(0.51±0.03),二者间存在显著差异(One-Way ANOVA Test,F1,28=38.865,P=0.000)。

表4 白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠的巢树利用与巢位特征

灰头小鼯鼠可以把巢口开在任何一个方向上,虽然以朝南和东南方向的频次较高,但仍未达到显著水平(χ2=13.733,df=7,P=0.056)(表5)。

表 5 白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠巢口方向的分布

3.2 巢树利用

单因素方差分析表明:灰头小鼯鼠巢树的冠幅(6.8±0.7) m显著大于对照树(4.9±0.5)m(F1,58=5.132,P=0.027)、通道数(4.3±0.2)也显著多于对照树(3.0±0.1)(F1,58=44.615,P=0.000), 但树高、胸径、第一主枝高等变量在巢树与对照树间差异均不显著(Pgt;0.05)。

研究还发现,在云南松、垂枝香柏等针叶树上,灰头小鼯鼠多利用树枝巢;在青冈栎(Cyclobalanopsisglauca)、川滇高山栎、五裂槭(Aceroliverianum)等阔叶树上灰头小鼯鼠常利用树洞巢(表4)。树枝巢巢树的平均胸径为(24.5±2.3) cm(n=15),显著小于树洞巢巢树的平均胸径(79.6±4.3) cm(n=15)(One-Way ANOVA Test,F1,28=149.558,P=0.000);树枝巢巢树的平均高度为(15.3±1.8) m(n=15), 也显著小于树洞巢巢树的平均高度(20.3±1.2) m(n=15)(One-Way ANOVA Test,F1,28=9.797,P=0.004)。

3.3 巢址选择

生境变量郁闭度、灌木盖度成功地用于构建灰头小鼯鼠巢址选择的逻辑斯蒂回归模型(NagelkerkeR2=0.699)(表6),模型总的判别正确率为90%(表7)。

表6白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠生境变量的逻辑斯蒂回归模型

Table6TheexplanatoryvariablesinthelogisticalregressionmodelofPetauristacanicepsnestsiteandrandomsiteinBaimaSnowMountainNatureReserve

变量Variable巢址样方Nestplot平均值Mean标准误SE随机样方Randomplot平均值Mean标准误SE优势率Oddsratio(OR)优势率95%置信区间95%C.IforOR系数Coefficient标准误SE常数Constant9.477E718.3674.791郁闭度canopycover3.530.0932.800.1010.0170.002—0.151-4.0931.124灌木盖度shrubcover2.870.1502.000.1660.1000.026—0.388-2.3000.690

表7 逻辑斯蒂回归模型预测分类表

4 讨论

4.1 巢及巢位特征

本研究表明,灰头小鼯鼠一般利用两种巢穴,即树洞巢和树枝巢。树枝巢常筑在乔木上部枝叶浓密的树冠处,再加上巢多数位于主枝上,这些特点不仅利于巢的稳定、减少风、雨等天气因素对鼯鼠的影响,而且还利于鼯鼠躲避天敌,为鼯鼠提供了安全的环境,这与缨耳松鼠(Sciurusaberti)[17]、北方飞鼠[12]、黑松鼠(Sciurusniger)[18]、赤腹松鼠(Callosciuruserythraeus)[16]、松鼠(Sciurusvulgaris)[19]等松鼠科动物的巢址特征是一致的。与之相比,树洞巢则一般开口于垂直树干,具有天然避风雨的作用,隐蔽性也比较高,所以树洞巢的相对巢高较树枝巢的低。尽管如此,灰头小鼯鼠的树枝巢和树洞巢的巢高间并不存在显著差异,离地面均较高,平均巢高为(11.3±0.8)m,而选择在较高的部位筑巢可能是为了方便滑翔和减少来自地面的干扰。

与树枝巢相比,树洞巢的巢口大小(10.8±0.5) cm显著比树枝巢的(12.1±0.1) cm小,而巢深(59.2±1.2) cm显著较树枝巢的(23.4±1.1) cm深。这可以解释为:与树枝巢相比,树洞巢相对较为暴露,因此,相对较小的巢穴入口,及较深的巢穴在避敌、避风及巢内温度的保持方面有重要的生态学意义[20- 21]。

尽管观察到的灰头小鼯鼠的巢口朝向东南和南方的较多,但经卡方检验表明:灰头小鼯鼠的巢口并没有方向偏好,这与加拿大亚伯达省西南的北方飞鼠相同[11],而与缨耳松鼠[17],赤腹松鼠[16],松鼠[19]等动物的巢口方向偏好朝南和朝东,阿巴拉切亚中央山脉的北方飞鼠[12]巢口偏好朝北方向不同。

4.2 影响巢树利用的因素

白马雪山自然保护区的灰头小鼯鼠倾向于在冠幅大、通道数多的树上筑巢。这可以解释为:巢树的冠幅大可为鼯鼠提供良好的隐蔽条件, 而通道数多能为鼯鼠提供更多可供选择的活动路线,并提高躲避天敌的成功率[11]。

本研究还发现,树枝巢的巢树均为针叶树种,而树洞巢在针叶树种和阔叶树种中均有发现,这与Patterson对北方飞鼠[11]的研究结果相一致。与针叶树相比,阔叶树更有利于树洞的形成[22],同时,本研究表明树洞巢巢树的胸径(79.6±4.3) cm显著大于树枝巢巢树的胸径(24.5±2.3) cm,这或许部分解释了为什么在阔叶树上树洞巢较多的原因,但要完全解释这一现象还需要开展进一步的研究。

4.3 影响巢址选择的因子

白马雪山自然保护区的灰头小鼯鼠喜欢在郁闭度高及灌木盖度高的环境中营巢。鼯鼠是一种树栖动物,郁闭度高的环境除了为鼯鼠提供了良好的隐蔽条件外,还提供了大量的食物[17]。同时,灌木盖度也是影响灰头小鼯鼠巢址选择的重要因素,灌木盖度高的地方,人和牲畜都去得少,从而减少了来自地面的干扰。

致谢:在野外工作中得到白马雪山保护区管理局、救护站的大力支持,以及护林员的热心帮助,特此致谢。

[1] Thorington R W Jr, Hoffman R S. Family Sciuridae // Wilson D E, Reeder D M, eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005: 754- 818.

[2] Hu J C. Mammalogy. Beijing: China Education and Culture Press, 2003: 173- 173.

[3] Götmark F, Blomqvist D, Johansson O C, Bergkvist J. Nest site selection: a trade-off between concealment and view of the surroundings? Journal of Avian Biology, 1995, 26(4): 305- 312.

[4] Rhodes B, O′Donnell C, Jamieson I. Microclimate of natural cavity nests and its implications for a threatened secondary-cavity-nesting passerine of New Zealand, the South Island saddleback. The Condor, 2009, 111(3): 462- 469.

[5] Steele M A, Koprowski J L. North American tree squirrels. Washington, London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001: 170- 170.

[6] Ramos-Lara N, Koprowski J L, Swann D E. Nest-site characteristics of the montane endemic Mearns′s squirrel (Tamiasciurusmearnsi): an obligate cavity-nester? Journal of Mammalogy, 2013, 94(1): 50- 58.

[7] Cowan I M. Nesting habits of the flying squirrel,Glaucomyssabrinus. Journal of Mammalogy, 1936, 17(1): 58- 60.

[8] Weigl P D, Knowles T W, Boynton A C. The Distribution and Ecology of the Northern Flying Squirrel,Glaucomyssabrinuscoloratusin the Southern Appalachians. Raleigh, North Carolina: North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, 1999: 63- 63.

[9] Meyer M D, North M P, Kelt D A. Nest trees of northern flying squirrels in Yosemite National Park, California. The Southwestern Naturalist, 2007, 52(1): 157- 161.

[10] Harestad A S. Nest site selection by northern flying squirrels and Douglas squirrels. Northwestern Naturalist, 1990, 71(2): 43- 45.

[11] Patterson J E H. Nest site characteristics and nest tree use by northern flying squirrels (Glaucomyssabrinus) in Southwestern Alberta, Canada. Northwest Science, 2012, 86(2): 144- 150.

[12] Menzel J M, Ford W M, Edwards J W, Menzel M A. Nest tree use by the endangered Virginia northern flying squirrel in the central Appalachian Mountains. The American Midland Naturalist, 2004, 151(2): 355- 368.

[13] Layne J N, Raymond M A V. Communal nesting of southern flying squirrels in Florida. Journal of Mammalogy, 1994, 75(1): 110- 120.

[14] Nakama S, Yanagawa H. Characteristics of tree cavities used byPteromysvolansoriiin winter. Mammal Study, 2009, 34(3): 161- 164.

[15] Li H W. Baima Snow Mountain Nature Reserve. Kunming: The Nationalities Publishing House of Yunnan, 2003: 366- 366.

[16] Wen Z X, Yin S J, Ran J H, Qi M D. Nest-site selection by the red-bellied squirrel (Callosciueuserythraeus) in Hongya County, Sichuan Province. Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2010, 29(5): 540- 545.

[17] Edelman A J, Koprowski J L. Selection of drey sites by Abert′s squirrels in an introduced population. Journal of Mammalogy, 2005, 86(6): 1220- 1226.

[18] Salsbury C M, Dolan R W, Pentzer E B. The distribution of fox squirrel (Sciurusniger) leaf nests within forest fragments in central Indiana. The American Midland Naturalist, 2004, 151(2): 369- 377.

[19] Rong K, Ma J Z, Zong C. Nest site selection by the Eurasian red squirrels (Sciurusvulgaris) in Liangshui Nature reserve. Acta Theriologica Sinica, 2009, 29(1): 32- 39.

[20] Kadoya N, Iguchi K, Matsui M, Okahira T, Kato A, Oshida T, Hayashi Y. A preliminary survey on nest cavity use by Siberian flying squirrels,Pteromysvolansorii, in forests of Hokkaido Island, Japan. Russian Journal of Theriology, 2010, 9(1): 27- 32.

[21] Halloran M E, Bekoff M. Nesting behaviour of Abert squirrels (Sciurusaberti). Ethology, 1994, 97(3): 236- 248.

[22] Mccomb W C, Lindenmayer D. Dying, dead, and down trees // Hunter M L, ed. Maintaining Biodiversity in Forest Ecosystems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999: 335- 375.

参考文献:

[2] 胡锦矗. 哺乳动物学. 北京: 中国教育文化出版社, 2003: 173- 173.

[15] 李宏伟. 白马雪山国家级自然保护区. 昆明: 云南民族出版社, 2003: 366- 366.

[16] 温知新, 尹三军, 冉江洪, 祁明大. 四川洪雅县赤腹松鼠巢址选择研究. 四川动物, 2010, 29(5): 540- 544.

[19] 戎可, 马建章, 宗诚. 凉水自然保护区松鼠巢址选择的特征. 兽类学报, 2009, 29(1): 32- 39.

NestsitecharacteristicsofPetauristacanicepsinBaimaSnowMountainNatureReserve

LI Yanhong, GUAN Jinke, LI Dayong, HU Jie*

KeyLaboratoryofSouthwestChinaWildlifeResourcesConservation(MinistryofEducation),InstituteofRareAnimalsandPlants.ChinaWestNormalUniversity,Nanchong,SichuanProvince637009,China

Nests provide a comfortable environment for individuals to raise young, avoid predators and rest, therefore, nesting is a critical facet of life for many species. A detailed understanding of nest site characteristics of species is important for the development of sound conservation and habitat management plan. The Grey-headed flying squirrel (Petauristacaniceps) is a small, nocturnal, arboreal mammal. It is found in southern, central and southwestern China. As a mammal in the list of National Protection of Useful or Have Important Economic and Scientific Research Values in China, little is known about the nest site use of this species. We conducted research on the nest site characteristics of the Grey-headed flying squirrel at three spatial scales (nest placement, nest tree, and nest site) in Baima Snow Mountain National Nature Reserve, Yunnan, China, in order to reveal the important ecological factors affecting the nest site selection of Grey-headed flying squirrel and further enrich wild species ecological and biological data. Data were collected from June to August and September to December 2012. The results showed that Grey-headed flying squirrel preferred two types of nest which included drey and cavity. All nests were found in the live trees. Dreys were typically made up of twigs, bark, moss and other materials. Dreys had larger openings (12.1±0.1) cm (n=15) than those of cavities(10.8±0.5) cm (n=15)(Mann-Whitney U testZ= -3.521,P=0.000), and shallower nests were built in the case of dreys (23.4±1.1) cm than cavities (59.2±1.2) cm (Mann-Whitney U testZ= -4.692,P=0.000). Most nests of the flying squirrel were built close to the main trunk (0.2±0.1) m and at a similar height (11.3±0.8 ) m (n=30). The average relative height of the nests is (0.67±0.03), indicating that Grey-headed flying squirrel usually built nest in the upper part of the tree. There was significant difference (One-Way ANOVA Test,F1,28=38.865,P=0.000)in the relative height between dreys (0.77±0.03) and cavities (0.51±0.03), but not (One-Way ANOVA Test,F1,28=2.195,P=0.150) in the average nest height. The Grey-headed flying squirrel did not show a significant preference (χ2=13.733,df=7,P=0.056) to the nest entrance direction. We found most cavities in the broadleaf trees (i.e.Quercusaquifolioides,Cyclobalanopsisglauca,Aceroliverianumi) and dreys only in the conifer species (i.e.pinusyunnanensis,Sabinapingii). The DBH (average diameter at breast height) and the average height of drey trees was significantly smaller than those of cavity trees. Characteristics of nest trees and nest sites were compared with randomly selected trees and sites. Grey-headed flying squirrel prefers to the nest trees with larger crown size and more access routes. The results of logistic regression analysis showed that differences in slope, slope position, slope aspect, and distance to water between nest sites and random sites was non-significant. On the contrary, nest sites used by Grey-headed flying squirrel differed from the random sites in that their larger canopy cover and higher shrub cover, suggesting that the Grey-headed flying squirrel seem to select nesting areas with high security and food availability.

Petauristacaniceps; nest site; Baima Snow Mountain Nature Reserve

国家自然科学基金项目(31200294)

2013- 06- 08;

2013- 07- 23

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: hu_jiebox@163.com

10.5846/stxb201306081474

李艳红,关进科,黎大勇,胡杰.白马雪山自然保护区灰头小鼯鼠的巢址特征.生态学报,2013,33(19):6035- 6040.

Li Y H, Guan J K, Li D Y, Hu J.Nest site characteristics ofPetauristacanicepsin Baima Snow Mountain Nature Reserve.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2013,33(19):6035- 6040.