Metacognition Theory and Research in Second Language Listening and Reading: A Comparative Critical Review

2013-12-04GOHLIEI

. . GOHLIEI

National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University,Singapore.National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University,Singapore

Listening and reading are two receptive skills in language learning and language use. Although their modalities differ, listening and reading share a number of cognitive processes required for language comprehension this has resulted in some commonalities in research emphases for the two skills. One such focus is the role of metacognition in self-regulated learning and comprehension performance. In this article theory postulated for metacognition and its manifestation in listening and reading are discussed. The article also reviews selected studies conducted in two important dimensions of metacognition, namely metacognitive knowledge and strategy use, and the impact that metacognitive instruction has on listening and reading comprehension performance. Results from the review for each skill are synthesised and compared in order to draw insights into the processes of learning to listen and read in another language. Based on this comparative review, the authors offer suggestions for enhancing process-based instructional practices in the language classroom and identify possible directions for future research into the role of metacognition in listening and reading specifically as well as second language comprehension as a whole.

Keywords: listening, reading, metacognition, metacognitive knowledge, strategy use, metacognitive instruction

Correspondence should be addressed to Professor Christine C. M. Goh, National Institute of Education, 1 Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616. Email: christine.goh@nie.edu.sg

INTRODUCTION

Language comprehension has been described as “the dynamic process of constructing coherent representations and inferences at multiple levels of text and context, within the bottleneck of a limited-capacity working memory” (Graesser & Britton, 1996, p. 352). This definition applies equally well to both listening and reading comprehension and recognises the interactivity of various cognitive processes for understanding to occur. These processes, however, are by necessity mediated and influenced by the medium in which language input is received and by the characteristics of these inputs which affect the limited capacity of working memory in unique ways. In processing spoken language, listeners have to engage in decoding and interpretation in real-time where acoustic signals are transient and traces of these sounds can be quickly lost resulting in comprehension difficulties. In contrast, readers who attend to written language have more time and less pressure to comprehend what is presented to them. In spite of these differences, there are similarities in the core processes of listening and reading, as described in the statement above, and these are reflected in many of the similar concerns in language learning research regarding how learners comprehend language in listening and reading and the effects instruction might have on improving these cognitive processes and their outcomes.

One area of focus is the role of metacognition in second language comprehension learning and performance. Researchers in listening and reading have reported on the metacognitive awareness of second language listeners and readers by employing similar methods of investigation such as think-aloud protocols, interviews, diaries/journals and self-reporting questionnaires (Anderson & Vandergrift, 1996; Carrell, 1989; Cross, 2009; Goh, 1997, 2000; Vandergrift, 1997, 2005; Zeng, 2012; Zhang, 2002, 2010; Zhang & Zhang, 2013). The effects of strategy instruction have also been examined for both skills where positive outcomes have been reported (e.g., Vandergrift & Tafaghodtari, 2010; Zhang, 2008). While there is now a sizeable body of research on metacognition for both listening and reading comprehension, there have been few attempts to synthesize and discuss the findings from these two related research strands. Such efforts can offer further insights into the similarities of listening and reading comprehension processes, learner factors in listening and reading performance, and inform pedagogies that can enhance language comprehension instruction in general. This article is therefore an attempt to do so by reviewing and comparing theoretical perspectives and research from the fields of second language listening and reading. It also offers suggestions on how applications of such perspectives can be harnessed to enhance instructional practices and further research in the common area of second language comprehension.

The review was done systematically in order to provide a coherent overview of the focus of research within the scope we have identified. As a considerable number of studies have been conducted on metacognition in listening and reading, particularly the latter, it would not have been possible to provide a comprehensive overview of all studies. Instead, we have applied two criteria when selecting the studies for inclusion in this systematic review: relevance and impact. We adopted a theoretical framework which foregrounds the importance of metacognitive knowledge and strategy use in scoping the review, and these two constructs are used as parameters when selecting the reviewed articles. Impact was ascertained by considering the frequency of citations for the articles that were first identified in order to further narrow the selection. Articles that have been published recently were also considered if they provided evidence for evaluating earlier research and represented contemporary knowledge and thinking in the areas under review. To improve objectivity when synthesizing the research evidence reviewed, each review section was independently summarized by one of the authors with the other evaluating the synthesis of the summaries. Each summary was then discussed before a final version was arrived at for the summaries and the overall conclusion.

SIMILARITIES IN LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION

Listening and reading are two important receptive skills in language learning and language use. Although seen to be different, listening and reading share similar cognitive processes which broadly fall into the categories of decoding and interpretation (Lund, 1991; Faerch & Kasper, 1986; Field, 2008; Hirai, 1999; Rost, 1990, 2013; Kintsch, 1998, 2008). Decoding is the process by which linguistic input is recognised and matched to words or meaning in an individual’s memory store of vocabulary or mental lexicon. Interpretation is the process by which the decoded linguistic input is used to construct an understanding of the message by drawing upon the individual’s memory store of knowledge and experience. These processes are represented in Anderson’s (2010) classic model for language comprehension in which he proposed three interrelated and recursive processes which occur when an individual receives linguistic input: perceptual processing, parsing and utilisation.Perceptualprocessingis the process of attending to linguistic signals which are held in the working memory and transforming this input into codes (in this case, words) that an individual recognises. In listening, chunks of speech also need to be segmented into recognisable words and phrases. Duringparsing, decoded words are transformed into a mental representation of the combined meaning of the words. This occurs when an utterance is processed according to syntactic structures and semantic or meaning cues. Parsing requires grammatical knowledge of a language in order to generate a meaningful representation of the intended meaning of the original sequence of language. Duringutilisationthe mental representation of the text is related to existing knowledge which is stored in the long-term memory. The listener or reader will interpret the overall meaning through high level processes such as making inferences and elaboration (Reder, 1980) and, if necessary, respond immediately to the speaker or the written message.

These three phases are interrelated and recursive, and can happen concurrently during a comprehension event. They are “by necessity partially ordered in time; however, they also partly overlap. Listeners can be making inferences from the first part of a sentence while they are already perceiving a later part” (Anderson, 2010, p. 388). Recent research on reading comprehension conceives reading as an interactive cognitive process in which readers interact with the text using their skills in word recognition, syntactic parsing, proposition formation and integration (i.e., constructing meaning at the clause-level using word and grammar information) as well as their background knowledge, and inference-making etc. (Grabe, 2009; Macaro & Erler, 2008; Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). Similar findings for listening have been reported, highlighting the importance of linguistic knowledge and inferencing skills that draw on prior knowledge and contextual cues across the three recursive and overlapping comprehension phases (Goh, 2005; Macaro, Graham, & Vanderplank, 2007; Vandergrift, 2007; Vandergrift & Goh, 2012).

METACOGNITION AND LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION

Metacognition is an important construct discussed in psychology and many interrelated fields of learning. Although there are variations in the way it has been explained, metacognition is considered by all to concern a person’s ability to know about and think about their own thinking, following Flavell’s (1979) definition of metacognition as “knowledge and cognition about cognitive phenomena” (p. 906). The vast literature in the related fields of psychology, education and second language learning has yet to proffer a unitary model for the construct of metacognition, but it does point to several fundamental characteristics that inform our understanding of what metacognition is and why it is important for learning. The general consensus among scholars is that metacognition enables learners to reflect on and evaluate their learning process constantly in order to gain more control of it by generating and using effective strategies (Hacker, Dunlosky, & Graesser, 2009). Additionally, metacognition helps develop learners’ motivation towards greater success (e.g., Schneider, 2008; Snowman, McCown, & Biehler, 2009) and has also been shown to be a reliable predictor of learning (Wang, Haertel, & Walberg, 1990).

The debate surrounding metacognition not only concerns the cognitive characteristics of this construct but also recognises the role of personal and social factors in learning (Veeman, Van Hout-Wolters, & Afflerbach, 2006). A person’s thinking and strategic behaviours in specific learning contexts are considered to be crucial to our understanding of metacognition and how it plays a role in learning. In defining a framework for listening instruction, Vandergrift and Goh (2012) proposed that an understanding of metacognition based on existing literature would recognise three essential cognitive characteristics, namely, metacognitive experience, metacognitive knowledge and strategy use. While metacognitive experience refers to involuntary fleeting sensations of thoughts about one’s thinking, metacognitive knowledge and strategy use are demonstrations of individuals’ multi-faceted understanding of themselves as learners and the tasks and actions needed to assist learning. Collectively, they constitute an individual’s metacognitive awareness.

Vandergrift and Goh’s (2012) framework for metacognition which is underpinned by Flavell’s (1979) conception of metacognition also draws heavily on reading comprehension literature (e.g., Afflerbach, Pearson, & Paris, 2008; Paris & Winograd, 1990) and is therefore just as relevant to our discussion of reading here. Metacognitive knowledge includes learners’ knowledge of person, tasks, and strategies, whereas strategy use can be viewed in terms of strategies for problem-solving, comprehension and learning. Metacognitive knowledge and strategy use are amenable to instruction and can lead to more effective comprehension. These cognitive characteristics underpin two important functions of metacognition, which are to self-appraise and self-manage our thinking and learning. According to Paris and Winograd (1990), self-appraisal refers to personal reflections on one’s own knowledge and abilities as well as making judgments about task and strategy factors affecting performance, while self-management is “metacognition in action”, which helps the individual “orchestrate cognitive aspects of problem solving” (p.17). The three dimensions of metacognition they identified(i.e., planning, evaluation, and regulation) also found support in many discussions about the taxonomy of planning, evaluating, and monitoring strategies in second language learning (Cohen, 1998; O’ Malley & Chamot, 1990; Oxford 1990, 2011; Macaro & Cohen, 2007; Wenden, 1991, 1998).

To show how these theoretical perspectives have influenced our understanding of second language comprehension, the rest of this article will elaborate on their application in listening and reading. We will focus on empirical research concerning language learners’ metacognitive knowledge, and the use of strategies in listening and reading. Following that, we will review studies that examined process-oriented instructional practices that develop learners’ metacognitive awareness and the effects that the practices have on their comprehension and learning. Our review is by necessity selective because there are now a considerable number of studies on L2 listening and particularly on reading, and an extensive review of existing literature is beyond the scope of this article. The review will therefore be guided by our focus on metacognitive knowledge and strategy use, as explained above.

MetacognitiveKnowledgeofL2ListenersandReaders

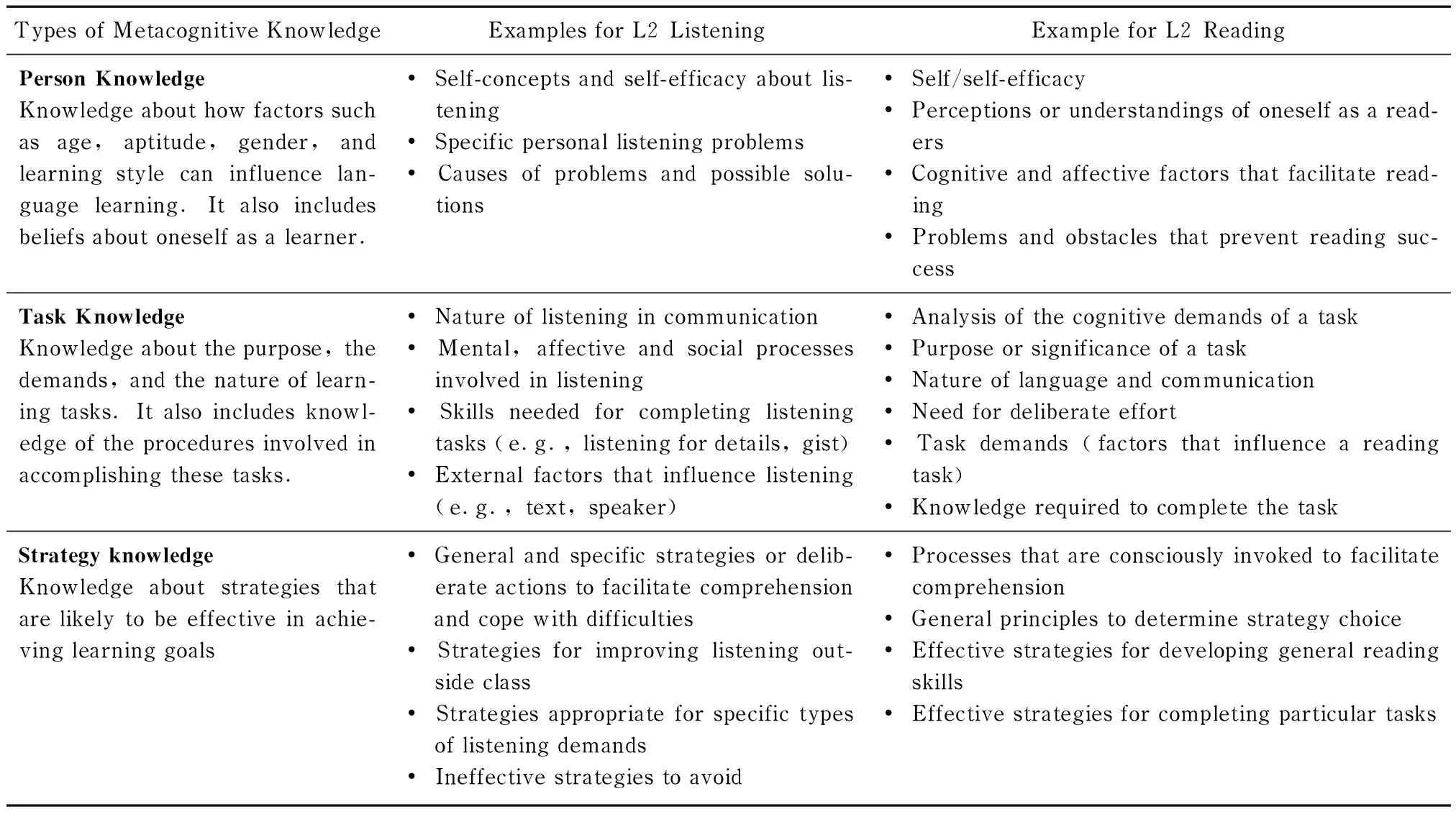

Metacognitive knowledge is knowledge about factors that influence one’s own learning, the nature of learning tasks, the demands exacted by particular learning tasks and strategies that can facilitate achievement. It is part of our “stored world knowledge that has to do with people as cognitive creatures and with their diverse cognitive tasks, goals, actions, and experiences” and can be categorised further as person, task and strategy knowledge (Flavell, 1979, p. 906). Applied to language learning, we may say that language learners possess person knowledge derived from their judgment of their learning abilities and how various factors affect the success or failure of learning activities, such as learning to listen and read. They also possess task knowledge about the purpose, demand and nature of listening and reading tasks, as well as strategy knowledge about actions that are useful for enhancing decoding and interpretation processes in order to achieve their listening or reading comprehension goals. Table 1 presents examples of the three types of metacognitive knowledge related to L2 listeners and readers.

Table 1 Three Types of Metacognitive Knowledge about L2 Listening and Reading

(Based on Goh, 1999, 2002b; Shoonen, Hulstijn, & Boossers, 1998; Zhang, 2010)

MetacognitiveKnowledgeandListening

L2 listeners demonstrate various levels of metacognitive knowledge about themselves and the listening process, an observation that has found empirical support among learners of different age groups and backgrounds. Vandergrift (2002) conducted a study to examine metacognitive knowledge demonstrated by beginning-level core French students’ (aged 10-12). 420 students in 17 different Grade 4-6 classes responded to at least one of three age-specific listening tasks, a reflective exercise, and a questionnaire. Due to the age of the participants, data was collected through teachers’ recordingof class discussions where the children reflected on how they understood the texts. The questionnaire asked the students to write comments about the task. These qualitative data were then analyzed for evidence of person knowledge, task knowledge and strategy knowledge. The results show that young as they were, the participants demonstrated a fairly high level of metacognitive knowledge, mainly concerning the task factors that affected their listening comprehension (task knowledge), the strategies used in their listening and what they could do to improve their performance in future listening tasks (strategy knowledge). They also demonstrated some understanding of themselves as L2 listeners (person knowledge).

In a study among older French students (aged between 16-18 years old), Graham (2006) asked a series of questions regarding their perceptions of listening in French in relation to their overall level of achievement in French. 595 high school students from the UK responded to the questionnaire and 28 of the participants were selected to participate in the interview section of the study based on teachers’ recommendation and their questionnaire responses. Semi-structured interviews were carried out to follow up on issues not fully explored in the questionnaire. The questionnaire data was analyzed quantitatively by means of frequencies and percentages calculation, chi-square test and Friedman two-way ANOVA test, whereas the interview data was analyzed qualitatively using the software package QSR NUD*IST. The researcher reported that the main reason learners gave for their success had to do with their perceptions of ability and efforts rather than strategy use while task difficulty and low ability were identified as reasons for failure in listening, suggesting that learners believed that the difficulty of task cannot be tackled by listening strategy use. In addition, it was found that none of the students attached much importance to the use of strategies, although one successful listener mentioned how different strategies helped her in listening activities. Based on the findings from this study, the author recommended that teachers should provide learners with chances of analysing their listening processes and identify the causes of their listening difficulties. She argued that if teachers hoped to improve learners’ listening skills, they would have to be aware of their beliefs and perceptions concerning the skill.

Several other studies have also provided empirical evidence for learners’ metacognitive knowledge about L2 listening (e.g., Cross, 2009; Goh, 1997; Vandergrift, Goh, Mareschal, & Tafaghodtari, 2006; Zeng, 2012) but few have investigated it in an Academic English context. One such attempt to examine learners’ metacognitive awareness about academic listening was by Aryadoust, Goh and Lee (2012), who devised an original self-rating questionnaire to elicit learner perceptions of their own academic listening performance. Known as the Academic Listening Self-rating Questionnaire (ALSA), the instrument was based on an exploratory model of integrated academic listening skills derived from extensive literature review. It invited respondents to report self-assessment ratings on a scale of (1) poor, (2) satisfactory, (3) good and (4) excellent for six related components of academic listening: cognitive processing skills, linguistic components and prosody, note-taking, lecture structure, relating input to other materials, and memory and concentration. Responses from 149 tertiary students showed that they were aware of many of the factors that influenced their success in lecture and academic discourse comprehension.

MetacognitiveKnowledgeandReading

Questionnaire surveys were also an effective means of eliciting language learners’ metacognitive knowledge about reading. In Schoonen, Hulstijn, and Bossers (1998), 685 students in grade 6, 8 and 10 in the Netherlands were invited to respond to a metacognitive knowledge questionnaire and take standardized reading comprehension tests in Dutch and English, and the native language and foreign language vocabulary tests. The aim of this study was to investigate how L1 and L2 reading proficiency could be explained by language-specific knowledge (as measured by L2 vocabulary tests) and metacognitive knowledge (as measured by the metacognitive knowledge questionnaire). The relationships between dependent and independent variables were studied by means of covariance structural analysis with latent variables. Results showed that metacognitive knowledge was capable of explaining additional variance in L2 reading comprehension apart from L2 vocabulary knowledge. In addition, it was found that metacognitive knowledge played a more important role in both L1 and L2 reading comprehension for older students. More importantly, this study also suggests that there might be a threshold level in that metacognitive knowledge may not be able to compensate for the lack of language knowledge if learners’ language-specific knowledge is below a certain level.

In a recent key study, Zhang (2010) investigated Chinese EFL students’ metacognitive knowledge system in relation to their reading experience. A total of 20 Chinese college students, 10 successful and 10 less successful readers as measured by their National Tertiary Matriculation Examinations (NTME) English subject scores and their College English Test (CET) Band 2 test results, were selected for the study through the procedure of stratified random sampling. They were asked to read two texts of about 500 words each before a 20-minute semi-structured interview was conducted. In order to elicit information about how various aspects of the participants’ metacognitive knowledge were related to EFL reading, the interview questions were phrased within the metacognitive knowledge systems framework based on Flavell (1979) and Wenden (1991). Similarly, the interview data was analyzed and classified according to the three categories of the metacognitive knowledge system of person/self, task and strategy. Results showed that the successful readers were quantitatively and qualitatively different from the less successful readers in their metacognitive knowledge about themselves as readers, cognitive tasks they handled and the strategic resources they could use. In other words, learners’ metacognitive knowledge has a strong relationship with their successful EFL reading comprehension.

InstrumentsforElicitingMetacognitiveKnowledge

As shown in the reviews of selected listening and reading studies above, individual learners possess metacognitive knowledge which can often be revealed through questionnaires. To find out learners’ existing metacognitive knowledge this way, listening and reading researchers have developed and validated useful tools to calibrate learners’ level of metacognitive knowledge. In L2 listening, the Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ) developed by Vandergriftetal. (2006) is an instrument that is underpinned by Flavell’s (1979) model of metacognitive knowledge and strategy use. The 21-item instrument that assesses L2 listeners’ metacognitive awareness and perceived use of strategies, comprises five distinct factors in listening: problem-solving, planning and evaluation, mental translation, person knowledge, and direct attention. Earlier, Sheorey and Mokhtari (2001) had also developed the Survey of Reading Strategies (SORS) to measure L2 learners’ metacognitive knowledge and perceived use of reading strategies. Grounded in Pressley and Afflerbach’s (1995) notable notion of constructively responsive reading, the 30-item SORS has three underlying factors: metacognitive strategies, cognitive strategies and support strategies, which have been updated respectively as global strategies, problem-solving strategies and support strategies by Mokhtari, Sheorey, and Reichard (2008). Phakiti (2003, 2008) has also provided new instruments for eliciting knowledge about strategy use during reading.

The MALQ and the SORS have been used in other studies respectively in listening (e.g., Baleghizadeh & Rahimi, 2011; Goh & Hu, 2013; Mareschal, 2007; O’Bryan & Hegelheimer, 2009; Zeng, 2012) and reading (e.g., Sheorey & Baboczky, 2008; Zhang, in press). Although developed primarily for the purpose of research, the MALQ and SORS can be used as a tool for both teaching and learning. For example, learners can use the MALQ and SORS to self-assess their level of metacognitive awareness and monitor their changes in strategy use over time. It can help improve learners’ metacognitive knowledge about the listening and reading tasks by raising their metacognitive awareness and strategy use. They can also use the information from the questions to evaluate their own process of reading and listening. More importantly, teachers can use the MALQ and SORS as diagnostic tools to assess students’ metacognitive awareness in order to provide appropriate instruction to raise students’ knowledge about themselves and listening and comprehension processes, as well as to enhance their use of comprehension strategies. The information obtained from the MALQ and SORS can also be used to evaluate students’ progress in becoming strategic listeners and readers.

Summary

Listening and reading researchers have adopted Flavell’s (1979) model of metacognitive knowledge successfully to explore learners’ metacognition and investigate its relationship with other variables such as proficiency. The model provided a robust theoretical framework for formulating questionnaire items that elicit learners’ knowledge about comprehension processes and strategy use and provided a means by which qualitative data from think-aloud protocols and interviews are analysed. Even in studies that did not explicitly adhere to the three knowledge categories, the overall focus on self-perceptions and understanding of cognitive processes and task demands clearly reflected the importance of the person/self, task and strategy knowledge dimensions of learners’ thinking being examined.

The research so far has therefore indicated that second language listeners and readers are aware, albeit to different extents, of how they attempt to process information from spoken and written texts. Comparisons of L2 listeners and readers of various ages and sociocultural backgrounds further show similarities in the metacognitive knowledge these learners possess, thus indicating that some of the processes which learners engage in are similar for listening and reading, and that these processes and the understanding of these processes are common across learners from different learning environments and contexts. Instruments such as the MALQ and SORS that have been used successfully to investigate the metacognition of learners from different backgrounds further suggest that it is possible to compare learners’ metacognitive knowledge about the respective skills in a consistent manner.

STRATEGY USE OF L2 LISTENERS AND READERS

The use of strategies is an important component of an individual’s metacognition. Paris, Wasik, and Turner (1996) argued that strategy use means taking selective and deliberate actions to achieve specific comprehension goals and entails awareness of when and how to call upon the assistance of these actions. As the body of works on strategy use has grown over the years, a number of strategy taxonomies on listening and reading strategies have also been developed respectively. Many of these taxonomies have as an organising principle three categories of strategies, namely cognitive, metacognitive and social-affective, as reflected in O’Malley and Chamot’s (1990) influential framework for learning strategies. A review of these taxonomies has shown some similarities within the literature of each of the two skills, revealing many striking commonalities among listening and reading strategies.

For listening, Vandergrift and Goh (2012) proposed 12 types of strategies based on a review of existing taxonomies (e.g., Goh, 1998, 2002; O’Malley & Chamot, 1990; Vandergrift, 1997, 2003; Young, 1997) that represent the mental processes and overt learning behaviours that second language listeners orchestrate to facilitate their comprehension and manage their listening development. These broad strategies are organized according to the role they play and consist of a combination of cognitive, metacognitive and social-affective strategies that have been identified in earlier research. See below for an explanation of each of these broad strategies; for details, refer to Vandergrift and Goh (2012, pp. 277-284).

1.Planning: Developing awareness of what needs to be done to accomplish a listening task, developing an appropriate action plan and/or appropriate contingency plans to overcome difficulties that may interfere with successful completion of a task.

2.Focusingattention: Avoiding distractions and heeding the auditory input in different ways, or keeping to a plan for listening development.

3.Monitoring: Checking, verifying, or correcting one’s comprehension or performance in the course of a task.

4.Evaluation: Checking the outcomes of listening comprehension or a listening plan against an internal or an external measure of completeness, reasonableness, and accuracy.

5.Inferencing: Using information within the text or conversational context to guess the meanings of unfamiliar language items associated with a listening task, to predict content and outcomes, or to fill in missing information.

6.Elaboration: Using prior knowledge from outside the text or conversational context and relating it to knowledge gained from the text or conversation in order to embellish one’s interpretation of the text.

7.Prediction: Anticipating the contents and the message of what one is going to hear.

8.Contextualization: Placing what is heard in a specific context in order to prepare for listening or assist comprehension.

9.Reorganizing: Transferring what one has processed into forms that help understanding, storage, and retrieval.

10.Usinglinguisticandlearningresources: Relying on one’s knowledge of the first language or additional languages to make sense of what is heard, or consulting learning resources after listening.

11.Cooperation: Working with others to get help on improving comprehension, language use, and learning.

12.Managingemotion: Keeping track of one’s feelings and not allowing negative ones to influence attitudes and behaviours.

Of the 12 strategies above, seven are directly associated with facilitation of comprehension processes in strategic listening: focusing attention, monitoring, evaluation, inferencing, elaboration, contextualisation and reorganising. In the field of reading, similar comprehension strategies have been identified by researchers (Pressley, 2002a, b, 2006; Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995) and these as well as others are presented in the list of strategies used by engaged readers that Grabe (2009, p. 228) proposed:

1. Read selectively according to goals.

2. Read carefully in key places.

3. Reread as appropriate.

4. Monitor their reading continuously and they are aware of whether or not they are comprehending the text.

5. Identify important information.

6. Try to fill in gaps in the text through inferences and prior knowledge.

7. Make guesses about unknown words.

8. Use text-structure information to guide understanding.

9. Make inferences about the author, key information, and main ideas.

10. Attempt to integrate ideas from different parts of the text.

11. Build interpretations of the text as they read.

12. Build main-idea summaries.

13. Evaluate the text and the author and, as a result, form feelings about the text.

14. Attempt to resolve difficulties

The two sets of strategies above provide an interesting comparison of what strategic listeners and readers do and show areas of overlap in the cognitive processes that learners engage for facilitating comprehension regardless of modality. For example, strategies 1, 2, 5, and 8 for reading may be compared to the listening strategy of focusing attention on the auditory input in different ways, such as attending to specific information or details during listening. The reading strategies of monitoring (4), evaluation (13) and inferencing (6, 7, 9) are also equally key to the listening process while the strategy for building main-idea summaries (12) is not unlike the strategy of reorganizing information from listening in order to aid understanding, storage and retrieval. When readers attempt to integrate ideas from different parts of the text (10), they are doing something similar to what listeners do when they contextualise what they hear in the local context of the unfolding auditory input. Unlike readers, however, listeners often have to take into account the context of interaction when processing what is heard because of face-to-face interactions.

Although Grabe’s list does not refer specifically to the strategy of elaboration (Reder, 1980), this cognitive process has been discussed often in relation to reading. With an elaborative inference, individuals add details to new information by drawing from their stored knowledge. The purpose of elaboration is to make an initial interpretation complete and personally meaningful. Although it does not make referential links to specific words or information in a text, elaboration is necessary for a coherent interpretation of a text (Garnham & Oakhill, 1992), and may therefore be considered to be a necessary strategy for language learners who often have to settle for less than complete understanding of a text because of their inadequate language proficiency. The affordances of the different modality of listening and reading result in an obvious difference in one area of strategy use: The permanence of the printed word allows readers to reread as often as it is needed while listeners’ only hope of re-listening often depends on whether a particular piece of information is repeated by the speaker. On the whole, nevertheless, there is evidence to show that the strategies identified in both fields of research share more similarities than differences. It also raises an interesting question as to whether learners could transfer comprehension strategies in one modality to another. In the following section some studies on strategy use in the respective skills are highlighted.

StrategyUseandListeningProficiency

In addition to providing inventories of effective strategies used in L2 listening and reading, researchers have also been interested in examining how learners’ strategy use is related to their listening and reading proficiency. Goh (2002) investigated the broad strategies and specific techniques, which she called tactics, that were used by 40 Chinese learners enrolled in an intensive English language programme in Singapore. Retrospective verbal data from listening to common texts were collected from all and analyzed to establish an inventory of strategies used before comparisons were made of two listeners of high and low listening ability respectively. 44 different listening tactics were identified from all the informants and then grouped conceptually under eight cognitive strategies and six metacognitive strategies. The two listeners being compared were found to have employed combinations of cognitive and metacognitive tactics, but the higher ability listener used a wider range of tactics appropriately whereas the lower ability listener demonstrated a narrower set of low-level tactics.

The combination or orchestration of strategies by listeners of different abilities was also examined by Vandergrift (2003). A group of 36 junior high school core French students in grade seven (12-13 years old) were classified into more skilled and less skilled listeners and asked to listen to the same three texts and provide think-aloud data individually when the recording was stopped at predetermined points. The data was transcribed and analysed according to a taxonomy of listening comprehension strategies (Vandergrift, 1997). Quantitative and qualitative analyses showed that although both skilled and less skilled listeners demonstrated similar kinds of knowledge of metacognitive and cognitive strategies, more skilled readers used more comprehension monitoring and managed their listening process better through employment of more metacognitive strategies. In addition, they also used more strategies of questioning elaboration to brainstorm logical possibilities of an interpretation. In contrast, less skilled listeners employed more direct translation and bottom-up strategies which did not help their comprehension.

The relationship between L2 listeners’ metacognitive knowledge about listening strategies and listening performance were examined quantitatively by Goh and Hu (2013). The study invited 113 Chinese ESL students between 18 and 20 years old to complete the listening component of an IELTS official sample test (University of Cambridge Local Examination Syndicate, 2001) before responding to the Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ) (Vandergriftetal., 2006). The analysis showed that metacognitive awareness had a direct and significant effect on listening performance, accounting for 22% of the variance of the listening test score, thus lending further and stronger support to earlier studies (Vandergriftetal., 2006; Zeng, 2012). A closer examination of the relationship between individual subscales of the MALQ and listening performance showed directed attention and problem solving strategies to be most important to the learners during listening.

StrategyUseandReadingProficiency

Similarly, reading researchers have also attempted to draw links between learners’ reading strategy use and their reading comprehension by developing instruments to gauge metacognitive awareness in reading. In an early study on metacognition and L2 reading, Carrell (1989) used the Metacognitive Awareness Questionnaire (MAQ) to compare L1 and L2 readers’ metacognitive knowledge and strategy use, and investigated the relationships between 45 Spanish native speakers’ and 75 English native speakers’ metacognitive awareness and their reading ability in both their L1 and L2. Two texts with multiple-choice questions were used as the instruments to measure subjects’ reading ability in L1 and L2. The questionnaire used in this study was a 36-item survey on a 1-5 Likert scale (1=strongly agree, and 5=strongly disagree) with four subscales: confidence, repair, effective, and difficulty strategies. Confidence strategies provided a measure of readers’ confidence in that language; repair strategies measured readers’ awareness of repair strategies; effective strategies tapped into their perception of effective/efficient strategies; and difficulty strategies examined the aspects of reading which made readers feel difficult. The researcher regressed subjects’ reading proficiency in their L1 and L2 on the four subscales of the MAQ. Her findings demonstrated that readers’ metacognitive awareness was closely related to their reading ability. The MAQ was also used in a subsequent study by Zhang (2002) to examine the effect of strategy use on Chinese EFL readers’ reading performance. His findings were consistent with Carrell’s (1989) in that learners’ reading performance was much influenced by their metacognition.

A questionnaire was also developed by Sheory and Mokhtari (2001) to examine the relationships between 150 US native English students’ and 152 ESL students’ reported use of reading strategies and their self-perceived reading ability in English. The data collection instrument was the 30-itemSurveyofReadingStrategies(SORS) designed to measure the type and frequency of reading strategies used by adolescent and adult ESL students while reading academic materials in English (Mokhtari, Sheorey, & Reichard, 2008). The overall internal reliability is .89 (Cronbach’s alpha). The SORS has three factors: global strategies, problem-solving strategies and support strategies. One of their major findings was that both ESL and US high-reading-ability students reported using more cognitive and metacognitive reading strategies than lower-reading-ability students.

Phakiti (2003) developed a 35-item strategy use questionnaire to examine the relationships between 384 Thai test takers’ strategy use and reading test performance. Based on the theory of human information processing (Gagnè, Yekovich, & Yekovich, 1993), his questionnaire included two categories: cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Cognitive strategies comprised two subscales: comprehending and retrieval while metacognitive strategies comprised two other subscales: planning and monitoring. He found that the use of cognitive and metacognitive strategies had a positive relationship to the reading performance which explained 15-22% of the test score variance.

Zhang and Zhang (2013) investigated the relationships between Chinese college test takers’ strategy use and test performance on the College English Test Band 4 Reading subtest. 209 Chinese college students sat for a reading comprehension test and answered a 30-item strategy use questionnaire by Phakiti (2008). It was found that two factors underlay test takers’ reading test performance: lexico-grammatical reading ability (LEX-GR) and text comprehension reading ability (TxtCOM). In addition, metacognitive strategy use had a significant and direct effect on cognitive strategy use, implying that the former performed an executive function over the latter. Monitoring strategies were found to have a significant effect on LEX-GR and evaluating strategies significantly affected TxtCOM, suggesting that metacognitive strategy use played an important role on the reading test performance.

Summary

A comparison of two sets of comprehension strategies revealed several similarities in listening and reading. These strategies had the function of managing comprehension processes through focusing attention, monitoring and evaluation and that of problem-solving through making inferences. Engaged listeners and readers also find ways to transform their interpretation and understanding in order to reorganise the processed information more systematically. These strategies are important for the utilisation phase during comprehension where information is stored for later retrieval or used immediately to generate a socially or textually appropriate response. Further, as shown in the empirical studies about strategies use in listening and reading, the general consensus among researchers is that strategy use is closely related to learners’ language performance (Anderson, 2005). In other words, more skilled listeners and readers can be distinguished from less skilled ones by their strategy use in the process of listening and reading.

An area of similarity in strategy use among more able listeners and readers is the prominence of metacognitive strategies and the quality of such strategies. A possible explanation for this is that learners less able at listening and reading may be impeded by low-level processing such as perceptual processing and are forced to expend a great deal more attentional resources on using direct problem solving strategies such as inferencing, thus leaving them little time to manage other aspects of comprehension process (Goh, 2000). Nevertheless, researchers in both listening and reading also point to the importance for learners to combine or orchestrate strategies in effective ways rather than focus on the use of individual strategies (Anderson, 1991; Vandergrift, 2003).

METACOGNITIVE INSTRUCTION FOR L2 LISTENING AND READING

A discussion of learners’ metacognition in learning to listen and read in another language is not complete without a consideration of how these concepts and research findings have been applied into teaching through a metacognitive approach. First implemented in reading classrooms, pedagogy informed by research on strategy use has played an important role in maximizing comprehension performance. In second language learning this type of instruction comprised procedures in which teachers incorporate language learning strategies into the teaching of language skills (Cohen, 1998; Oxford, 2001; Wenden, 2002). Vandergrift and Goh (2012) defined metacognitive instruction as pedagogical procedures that can raise learners’ awareness of the comprehension process by training learners directly to use relevant strategies as well as helping them develop their metacognitive knowledge. They reassert the views of many scholars and researchers that metacognitive instruction is an important way of encouraging learners to become more self-regulated in their learning process by taking on an active role in facilitating their comprehension process and overall progress. Reading research shows that metacognitive instruction has positive effects on improving readers’ comprehension in L1 and L2 through strategy instruction programmes (e.g., Brown & Palinscar, 1982; Carrell, Pharis, & Liberto, 1989) and it has long been regarded as important for helping learners internalise monitoring and controlling processes for effective comprehension (Pressley, 2002b). The same arguments have been put forward in second language listening where strategy instruction can benefit all learners in terms of improving listening performance and developing a stronger sense of control over their listening processes (Mendelsohn, 1994, 2006; Chamot, 1987; Graham, Santos, & Vanderplank, 2011; Vandergrift, 2004).

MetacognitiveInstructioninListening

To investigate the effects of metacognitive instruction on listening comprehension, researchers have conducted an array of studies with qualitative, quantitative or mixed designs. For example, a small-scale study was conducted by Goh and Taib (2006) to explore the benefits of metacognitive instruction in listening among young language learners. Ten primary school students aged between 11 and 12 years old, five boys and five girls, participated in the study and were involved in a series of eight process-based listening lessons a few months prior to a government examination. Three stages were included in the lesson: Listen and answer, reflect, and report and discuss. The usefulness of the instruction was examined through students’ reflection on what they had learnt from the listening lessons and the comparison of their listening test scores before and after the intervention. It was found that the process-based instruction not only increased learners’ confidence and metacognitive knowledge but also improved their listening test scores, particularly for the weaker students. As this was an exploratory study with a small group of learners, the researchers did not examine the statistical significance of these improvements. Nevertheless, the qualitative data showed that these young learners had benefited from the innovative pedagogy for listening.

Cross (2009) investigated the effect of strategy instruction on Japanese advanced learners’ listening comprehension of BBC news videotexts over a 10-week period in a classroom-based quasi-experiment. Fifteen Japanese learners of advanced level, aged between 26 to 45 years old, were involved in this study. Seven participants from the experimental group received 12 hours of listening strategy instruction through a strategy-based approach advocated by Mendelsohn (1994) which included explicit presentation, practice, and review of listening strategies. Results showed that both the experimental and control group made significant improvement on the listening post-test. There was, however, no significant difference between the experimental and control groups in their post-test scores. Cross explained that the small number of participants could have had an impact on individual variability leading to some distortion of the results, but that a more important reason for the achievement by both groups was the listening pedagogy used for both groups which encouraged interaction within the groups to share and check comprehension and monitor their own performance. This could have created a heightened collective awareness of listening strategies leading to adjustments in their approach to the listening tasks and improvements in ability. The quasi-experimental design used in this study proved to be effective in revealing the effects of metacognitive instruction on listening comprehension. The author acknowledged that the low number of participants in both experimental and design groups might have led to distorted interpretation oft-test results.

Cross (2009) argued that instead of an explicit strategy-based approach, it would be more instructive to integrate the teaching of strategies and awareness raising into listening lessons. Such an embedded approach was taken by Vandergrift and Tafaghodtari (2010) who investigated the effects of a metacognitive pedagogical sequence (Vandergrift, 2004) on the listening abilities of 106 university-level French L2 students. 59 students from the experimental group were guided through in their listening following the sequence of prediction/planning, monitoring, evaluating, and problem solving while the other 47 students from the control group did not receive any guided instruction. The Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ) was used as a measure of participants’ development of metacognition in the teaching process. After controlling differences in participants’ listening ability, it was found, as hypothesized, that the experimental group performed significantly better than the control group in their listening comprehension. A closer examination of the post-test scores showed that the less skilled listeners made greater improvement than their more skilled counterparts. There was also evidence of increased metacognitive awareness.

Positive effects of metacognitive instruction were also reported by Zeng (2012) in a study among college-level EFL learners in China. As part of this study, he implemented a two-month self-regulated learning intervention programme involving 24 participants to examine their progress both in metacognitive knowledge and listening performance. This programme made use of an individual Self-Regulated Listening Portfolio (SRLP) which consisted of weekly listening plans, a self-directing listening guide with embedded metacognitive prompts designed to guide learners in their weekly listening, and listening diary prompts which enabled learners to reflect on and record their weekly listening activities in and beyond the classroom. The MALQ was also used as an awareness-raising tool to help direct learners’ approach to listening tasks, and to increase self-regulated use of comprehension strategies. After two months of intervention, independent samplest-tests and paired samplest-tests showed that the group that received explicit metacognitive instruction in planning, monitoring and evaluating their listening efforts significantly outperformed the control group in listening performance (p<.01). Analysis of the pre-test and post-test MALQ responses also showed an increased level of metacognitive knowledge and more metacognitive strategy use, indicating stronger self-regulatory ability for the 12 learners in the intervention group. The quantitative results for this small sample were further supported by their written reflection on the value of the self-regulated listening programme and their improved understanding of the nature, demand and complex processes of L2 listening.

MetacognitiveInstructioninReading

Researchers in reading comprehension have shown similar interest in examining how metacognitive instruction can enhance learners’ metacognitive awareness and improve their reading comprehension. Kern (1989) investigated the effects of strategy instruction on reading comprehension of university-level students of French as a second language. Of the 53 intermediate-level students, 26 formed the experimental group and received explicit instruction in reading strategy use apart from the normal course content. The control group only had access to the same listening practice material. To measure their reading ability, all participants were given a “reading task interview”, which incorporated think-aloud and text interview procedures at the beginning and end of the semester. On the basis of their pre-test comprehension scores, participants were divided into low, middle and high ability groups. Results showed that explicit instruction in comprehension strategies had a strong and positive effect on L2 readers’ comprehension ability and could improve learners’ reading comprehension performance in French. However, it was found that only the low ability group made significant improvement in reading comprehension. Kern suggested that this might be that the middle and high ability students had already employed effective reading strategies before the instruction. Kern’s study provided support for the positive effects of explicit instruction of reading strategies on reading comprehension although the interpretation of quantitative analyses would have been more convincing with a larger sample.

In a study among college students, Dryer and Nel (2003) examined the effect of a 13-week reading strategy instruction module on college ESL learners’ reading comprehension. 131 first-year students taking the English for Professional Purposes course at a South African university received a combination of cognitive and metacognitive reading strategy instruction offered in a technology-enhanced environment. The strategy instruction consisted of study guides, an online management system and personal contact with tutors. The students were divided into experimental and control groups and additionally categorized as “successful” and “at risk” groups. Results showed that both successful and at risk students in the experimental group performed significantly better than the control group. Students who received instruction also demonstrated changes in their choice and employment of reading strategy use. Dryer and Nel’s (2003) study offered insights into how strategy instruction can enhance reading comprehension in a technology-enhanced environment. However, since they did not control participants’ proficiency level, it is possible that the independentt-test result might be confounded by the uncontrolled variable, leading to distorted interpretation of the research findings.

Zhang (2008) conducted a two-month strategic reading instruction and investigated its pedagogical effects on learners’ reading performance among 99 EAP Chinese students in Singapore. Set within a constructivist framework, the instruction program included reading strategies selected with reference to pre-, while, or post-stage in reading. The experimental group, consisting of 50 students, received reading strategy training integrated with language instruction whereas the control group, including 49 students, was only exposed to traditional teacher-centred mode of language instruction. All instruction sessions were either video- or audio-recorded. To assess the instructional effect, a list of reading strategies identified from the literature (e.g., Carrell, 1998; Cohen, 1998) was administered among participants in a questionnaire format and four questions ascertaining their interest and willingness were asked. Results showed that the strategy-based intervention improved the ESL learners’ use of reading strategies and their reading performance. This study suggested that it is important that teachers acknowledge and incorporate sociocultural factors brought by learners in strategy-based intervention.

Reports on the benefits of reading strategy instruction were not limited to adult and tertiary-level language learners. Macaro and Erler (2008) conducted a longitudinal intervention study of reading comprehension among 62 young-beginner learners of French as a foreign language in England. The learners, aged between 11 and 12, participated in a special reading programme over 14 months that included reading strategy instruction alongside the children’s normal reading curriculum. This special programme was conceived as “high scaffolding” such that “when the students engaged with the texts, they were reminded to try out strategy combinations and they received feedback about their strategy use” (p.111). Data on their French reading comprehension performance, strategies used for reading and attitudes towards French was collected before and after the intervention. When the findings were compared with a group of 54 students who did not participate in the intervention, the researchers found that these learners demonstrated improved reading comprehension and modified strategy use in terms of how the strategies were combined or orchestrated and improved attitudes towards reading in French. It was noted, however, that the range and standard deviations of the scores were high and that a minority of the learners in the intervention group did not seem able to orchestrate the combinations of strategies to meet task requirements.

Summary

Metacognitive instruction has been shown to enhance listening and reading comprehension of L2 learners of various age groups, proficiency levels and backgrounds. Although improvement in comprehension performance remains a key goal for many, it is clear that learners can also develop greater confidence and motivation when they feel that they are more in control of the processes involved in listening and reading. Positive affect such as this can have an indirect impact on learners’ listening and reading development, and therefore should not be undervalued. As regards the method for strategy instruction, there does not seem to be a preferred way for improving strategy knowledge and strategy use. The research so far has adopted both direct as well as embedded strategy instruction. In the former, learners are taught a specific set of strategies useful for comprehension (e.g., Cross, 2009; Kern, 1989; Zhang, 2008) while the embedded method offers naturalistic guided practice in which metacognitive processes are activated and rehearsed (e.g., Goh & Taib, 2006; Vandergrift & Tafaghodtari, 2010). Research findings also indicated that while all learners can benefit from metacognitive instruction, it is the weaker learners who seem to be most helped by it. In spite of the many encouraging reports from empirical research, there is an on-going debate about the place of strategy instruction in the curriculum (e.g., Cross, 2012; Renandya, 2012).

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

This article provides a review of theory and research related to the place of metacognition in listening and reading comprehension processes. It focuses specifically on metacognitive knowledge and strategy use, two key indicators of an individual’s metacognition in action when he or she is learning to listen and read in a second language. It also highlights the impact of metacognitive instruction that research has shown to improve language comprehension and affect. This review has also shown that listeners and readers share many similar kinds of knowledge regarding comprehension processes. Their metacognitive knowledge is related to their understanding of themselves as listeners/readers, the nature and demands of listening/reading tasks and the strategies they have recourse to when attempting to achieve their comprehension goals. Listeners and readers also reported using many similar strategies but differences in the deployment of these strategies have been observed.

As two different modalities, listening and reading differ in the acoustic and printed stimuli that are characteristic of each skill; hence, leading to different cognitive demands in the processing of linguistic information. The transience of spoken messages as opposed to the permanence of the written text means that listeners have to process language under a much greater cognitive constraint where sounds that have been initially recognised could easily be lost as more input is being attended to. L2 readers, on the other hand, can get the main idea by skimming the complete text and rereading it whenever they wish to. These challenges that listeners face can in turn influence the types of strategies that are used more frequently and may explain why selective attention strategies are more important to L2 listeners than to L2 readers. Cognitive processing also differs during reading and listening because of the sound system of a language. Learners who can read the written language may still have difficulty processing familiar words when these words are heard. Whereas readers can rely on main ideas and details gleaned from the written text to construct understanding, listeners generally have fewer details to build a mental model with which to construct their interpretation. They will therefore resort to more top-down and prior knowledge-based processes and are more likely to depend on inference-making and elaboration strategies, compared with L2 readers.

To sum up, evidence from the studies points to more similarities than differences concerning L2 learners’ metacognitive knowledge and strategy use across the two modalities. Research so far also suggests that metacognitive instruction is beneficial to both modes of skill development, although caution is still needed about its efficacy given the small number of studies to date. For more definitive conclusions to be drawn, further studies need to be added to the current literature so that comparisons between the two modes of receptive language skills can be made directly.

Based on the above review some possible directions for teaching and research are suggested below. First, with the help of instruments such as the MALQ and SORS, teachers will find it possible to understand what their students already know or do about listening and reading comprehension processes. Second, while metacognitive instruction should be encouraged in the classroom, teachers need to decide carefully how it should be carried out by considering their students’ prior knowledge, experience and language ability. In addition, it would be useful to bear in mind the differences in the cognitive and social processes involved in listening and reading and focus on groups of strategies that can address these processes directly and most efficiently.

Although recent research has provided some new insights into the role of metacognition in L2 listening and reading, many of the studies are exploratory in nature and the questions that motivated these studies need to be further examined through more studies across diverse contexts. In this regard, it may be useful for some replication studies to be conducted in order to strengthen the existing knowledge base concerning the development of metacognitive awareness and strategic comprehension in different cultural and educational contexts. Findings from these studies will also offer valuable insights into the issues surrounding the teaching and development of listening and reading. Although we have seen studies emerging now which use validated questionnaires and previously published qualitative methods for eliciting data on metacognitive awareness, the number has been relatively small. As some of these studies have shown how metacognition accounted for part of the observed variance in listening and reading comprehension, more studies of this kind will offer further insights into the extent of the role that metacognition plays in language comprehension and development, thereby allowing more definitive statements to be made about the relationship and its pedagogical implications.

What is greatly lacking right now is research that examines both listening and reading comprehension together that can enable further comparisons to be made. For example, in spite of some differences between L2 listening and reading, the broad strategies involved in the two modalities appear to be similar. Research could therefore be conducted to compare L2 listeners’ and readers’ employment of strategies or examine the effects of metacognitive instruction on listening and reading comprehension, and the potential transferability of strategies across the two modalities. This can provide useful pedagogical insights into the teaching of receptive skills and lead to new directions for material development. In addition, as technologies provide endless opportunities to make use of multimedia materials in real-life situations, future research can put more emphasis on the metacognitive approach to L2 listening and reading in multimedia environments. Some attempts have already been made in this respect for reading (e.g., Coiro, 2003; Coiro & Dobler, 2007; Huang, Chern, & Lin, 2009), but more need to done for listening to enable further comparisons between the two skills.

Last but not least, it may be instructive for researchers to adopt a common conceptual framework when investigating metacognition so that comparisons can be more readily made across existing and future studies. Through this and other measures mentioned above, we can look forward to deepening our understanding about the construct of metacognition for language comprehension and second language development, thereby strengthening the theory-practice nexus not only in the metacognitive approach but also in second language comprehension instruction as a whole.

REFERENCES

Anderson, N. J. (1991). Individual differences in strategy use in second language reading and testing.ModernLanguageJournal, 75, 460-72.

Anderson, J.R. (2010).Cognitivepsychologyanditsimplications(7th ed.). New York: Worth.

Anderson, N. J. (2005). L2 learning strategies. In E. Hinkel (Ed.),Handbookofresearchinsecondlanguageteachingandlearning(pp. 757-771). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Anderson, N. J. & Vandergrift, L. (1996). Increasing metacognitive awareness in the L2 classroom by using think-aloud protocols and other verbal report formats. In R. L. Oxford (Ed.),Languagelearningstrategiesaroundtheworld:Cross-culturalperspectives(pp. 3-18). Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Afflerbach, P., Pearson, P. D., & Paris, S. G. (2008). Clarifying differences between reading skills and reading strategies.TheReadingTeacher, 61, 364-373.

Aryadoust, V., Goh, C.C.M., & Lee, O. K. (2012). Developing an academic listening self-assessment questionnaire: A study of modelling academic listening.PsychologicalTestandAssessmentModeling, 54, 227-256.

Baleghizadeh, S. & Rahimi, A. H. (2011). The relationship among listening performance, metacognitive strategy use and motivation from a self-determination theory perspective.TheoryandPracticeinLanguageStudies, 1, 61-67.

Brown, A. L. & Palinscar, A. S. (1982). Inducing strategic learning from text by means of informed, self-control training.TopicsinLearningandLearningDisabilities, 2, 1-17.

Carrell, P. L. (1989) Metacognitive awareness and second language reading.TheModernLanguageJournal, 73, 121-13.

Carrell, P., Pharis, B., & Liberto, J. (1989). Metacognitive strategy training for ESL reading.TESOLQuarterly, 23, 647-678.

Chamot, A.U. (1987). The learning strategies of ESL students. In A. Wenden & J. Rubin (Eds.),Learnerstrategiesinlanguagelearning. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Cohen, A. D. (1998).Strategiesinlearningandusingasecondlanguage. London: Longman.

Coiro, J. (2003). Reading comprehension on the Internet: Expanding our understanding of reading comprehension to encompass new literacies.TheReadingTeacher, 56, 458-464.

Coiro, J. & Dobler, E. (2007). Exploring the online reading comprehension strategies used by sixth grade skilled readers to search for and locate information on the Internet.ReadingResearchQuarterly, 42, 214-257.

Cross, J. D. (2009). Effects of listening strategy instruction on news videotext comprehension.LanguageTeachingResearch, 13, 151-176.

Cross, J. D. (2012). Listening strategy instruction (or extensive listening?): A response to Renandya (2011).ELTWorldOnline.com, 4. http:∥blog.nus.edu.sg/eltwo/2012/02/22/five-reasons-why-listening-strategy-instruction-might-not-work-with-lower-proficiency-learners.

Dryer, C. & Nel, C. (2003). Teaching reading strategies and reading comprehension within a technology-enhanced learning environment.System, 31, 349-365.

Field, J. (2008).ListeningintheLanguageClassroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry.AmericanPsychologist, 34, 906-911.

Gagnè, E. D., Yekovich, C. W., & Yekovich, F. R. (1993).Thecognitivepsychologyofschoollearning. New York: Harper Collins.

Garnham, A. & Oakhill, J.V. (1992). Discourse representation and text processing from a “mental models” perspective.LanguageandCognitiveProcesses, 7, 231-255.

Goh, C. (1997). Metacognitive awareness and second language listeners.ELTJournal, 51, 361-369.

Goh, C. (1998). How ESL learners with different listening abilities use comprehension strategies and tactics.LanguageTeachingResearch, 2, 124-147.

Goh, C.C.M. (1999). What learners know about the factors that influence their listening comprehension.HongKongJournalofAppliedLinguistics, 4, 17-42.

Goh, C.C.M. (2000). A cognitive perspective on language learners’ listening comprehension problems.System, 28, 55-75.

Goh, C.C.M. (2002). Exploring listening comprehension tactics and their interaction patterns.System, 30, 185-206.

Goh, C.C.M. (2005). Second language listening expertise. In K. Johnson (Ed.),Expertiseinsecondlanguagelearningandteaching(pp. 64-84). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goh, C.C. M. (2008). Metacognitive instruction for second language listening development: Theory, practice and research implications.RELCJournal, 39, 188-213.

Goh, C. & Hu, G. (2013). Exploring the relationship between metacognitive awareness and listening performance with questionnaire data.LanguageAwareness, doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.769558.

Goh, C. & Taib, Y. (2006). Metacognitive instruction in listening for young learners.ELTJournal, 60, 222-232.

Graham, S. (2006). Listening comprehension: The learners’ perspective.System, 34, 165-182.

Graham, S., Santos, D., & Vanderplank, R. (2011). Exploring the relationship between listening development and strategy use.LanguageTeachingResearch, 15, 435-456.

Grabe, W. (2009).Readinginasecondlanguage:Movingfromtheorytopractice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graesser, A.C. & Britton, B.K. (1996). Five metaphors for text understanding. In B.K. Britton & A.C. Graesser (Eds.).ModelsofUnderstandingText. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hacker, D. J., Dunlosky, J., & Graesser, A.C. (Eds.). (2009).Handbookofmetacognitionineducation. Mahwah: Erlbaum/Taylor & Francis.

Hirai, A. (1999). The relationship between listening and reading rates of Japanese EFL learners.TheModernLanguageJournal, 83, 367-384.

Huang, H., Chern, C., & Lin, C. (2009). EFL learners’ use of online reading strategies and comprehension of texts: An exploratory study.Computer&Education, 52, 13-26.

Kern, R. G. (1989). Second language reading strategy instructions: Its effects on comprehension and word inference ability.ModernLanguageJournal, 73, 135-149.

Kintsch, W. (1998).Comprehension:Aparadigmforcognition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kintsch, W. (2008). Symbol systems and perceptual representations. In M. De Vega, A. Glenberg, & A. Graesser (Eds.),Symbolsandembodiment(pp.145-164). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lund, R.J. (1991). A comparison of second language listening and reading comprehension.TheModernLanguageJournal, 75, 196-204.

Macaro, E. & Cohen, A. D. (Eds.). (2007).Languagelearnerstrategies: 30yearsofresearchandpractice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Macaro, E. & Erler, L. (2008). Raising the achievement of young-beginner readers of French through strategy instruction.AppliedLinguistics, 29, 90-119.

Macaro, E., Graham, S., & Vanderplank, R. (2007). A review of listening strategies: Focus on sources of knowledge and on success. In E. Macaro & A. Cohen (Eds.),Languagelearnerstrategies: 30yearsofresearchandpractice(pp. 165-185). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mareschal, C. (2007).Studentperceptionsofaself-regulatoryapproachtosecondlanguagelisteningcomprehensiondevelopment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa, Ontario.

Mendelsohn, D. (1994).Learningtolisten:Astrategy-basedapproachforthesecond-languagelearner. San Diego: Dominie Press.

Mendelsohn, D. J. (2006). Learning how to listen using listening strategies. In E. Usó-Juan & A. Martinez-Flor (Eds.),Currenttrendsinthedevelopmentandteachingofthefourlanguageskills(pp. 75-89). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mokhtari, K., Sheorey, R., & Reichard, C.A. (2008).Measuring the reading strategies of first and second language readers. In K. Mokhtari & R. Sheorey (Eds.),Readingstrategiesoffirst-andsecondlanguagelearners(pp. 43-65). Norwood: Christopher-Gordon.

O’Bryan, A. & Hegelheimer, V. (2009). Using a mixed methods approach to explore strategies, metacognitive awareness and the effects of task design on listening development.CanadianJournalofAppliedLinguistics, 12, 9-37.

O’Malley, J. M. & Chamot, A. U. (1990).Learningstrategiesinsecondlanguageacquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Malley, J. M. & Chamot, A. U. (1990).Learningstrategiesinsecondlanguageacquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. L. (1990).Languagelearningstrategies:Whateveryteachershouldknow. New York: Newbury House.

Oxford, R. L. (2001). Language learning strategies. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.),TheCambridgeguidetoteachingEnglishtospeakersofotherlanguages(pp. 166-172). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. L. (2011).TeachingandResearchingLanguageLearningStrategies. London: Longman.

Paris, S. G., Wasik, B., & Turner, J. (1991). The development of strategic readers. In R. Barretal. (Eds.),Handbookofreadingresearch(Vol. Ⅱ, pp.609-40). New York: Longman.

Paris, S.G. & Winograd, P. (1990). How metacognition can promote academic learning and instruction. In B.F. Jones & L. Idol (Eds.),Dimensionsofthinkingandcognitiveinstruction(pp.15-51). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Phakiti, A. (2003). A closer look at gender differences in strategy use in L2 reading.LanguageLearning, 53, 649-702.

Phakiti, A. (2008). Construct validation of Bachman and Palmer’s (1996) strategic competence model over time in EFL reading tests.LanguageTesting, 25, 237-272.

Pressley, M. (2002a). Comprehension strategy instruction: A turn-of-the-century status report. In C. Block & M. Pressley (Eds.),Comprehensioninstruction:Research-basedbestpractices(pp. 11-27). New York: Guilford Press.

Pressley, M. (2002b). Metacognition and self-regulated instruction. In A. Farstrup & S. Samuels (Eds.),Whatresearchhastosayaboutreadinginstruction(3rd ed., pp. 291-309). Neward: International Reading Association.

Pressley, M. (2006).Readinginstructionthatworks:Thecaseforbalancedteaching(3rd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Pressley, M. & Afflerbach, P.(1995).Verbalprotocolsofreading:Thenatureofconstructivelyresponsivereading. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Reder, L. M. (1980). The role of elaboration in the comprehension and retention of prose: A critical review.ReviewofEducationalResearch, 50, 5-53.

Renandya, W. (2012). Five reasons why listening strategy instruction might not work with lower proficiency learners.ELTWorldOnline.com, 3. http:∥blog.nus.edu.sg/eltwo/2012/02/22/five-reasons-why-listening-strategy-instruction-might-not-work-with-lower-proficiency-learners/.

Rost, M. (1990).Listeninginlanguagelearning. London: Longman.

Sheorey, R. & Mokhtari, K. (2001). Coping with academic materials: Differences in the reading strategies of native and non-native readers.System, 29, 431-449.

Sheorey, R. & Baboczky, E. S.(2008).Metacognitive awareness of reading strategies among Hungarian College Students. In K. Mokhtari & R. Sheorey (Eds.),Readingstrategiesoffirst-andsecondlanguagelearners(pp. 43-65). Norwood: Christopher-Gordon.

Shoonen, R., Hulstijn, J. H., & Boossers, B. (1998). Metacognitive and language-specific knowledge in native and foreign language reading comprehension: An empirical study among Dutch students in grades 6, 8, and 10.LanguageLearning, 48, 71-106.

Schneider, W. (2008). The development of Metacognitive knowledge in children and adolescents: Major trends and implications for education.Mind,BrainandEducation, 2, 114-121.

Snowman, J., McCown, R., & Biehler, R. (2009).PsychologyAppliedtoTeaching(12th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Vandergrift, L. (1997). The strategies of second language (French) listeners: A descriptive study.ForeignLanguageAnnals, 30, 387-409.

Vandergrift, L. (2002). It was nice to see that our predictions were right: Developing metacognition in L2 listening comprehension.CanadianModernLanguageReview, 58, 556-575.

Vandergrift, L. (2003). Orchestrating strategy use: Toward a model of the skilled second language listener.LanguageLearning, 53, 463-496.

Vandergrift, L. (2004). Learning to listen or listening to learn?AnnualReviewofAppliedLinguistics, 24, 3-25.

Vandergrift, L. (2005). Relationships among motivation orientations, metacognitive awareness and proficiency in L2 listening.AppliedLinguistics, 26, 70-89.

Vandergrift, L. (2007). Recent developments in second and foreign language listening comprehension research.LanguageTeaching, 40, 191-210.

Vandergrift, L. & Goh, C. C. M. (2012).Teachingandlearningsecondlanguagelistening:Metacognitioninaction. New York: Routledge.

Vandergrift, L., Goh, C., Mareschal, C., & Tafaghodtari, M. H. (2006). The Metacognitive Awareness Listening Questionnaire (MALQ): Development and validation.LanguageLearning, 56, 431-462.

Vandergrift, L., & Tafaghodtari, M. H. (2010). Teaching learners how to listen does make a difference: An empirical study.LanguageLearning, 65, 470-497.

Veenman, M. V. J., Van Hout-Wolters, B. H. A. M., & Afflerbach, P. (2006). Metacognition and learning: Conceptual and methodological considerations.MetacognitionandLearning, 1, 3-14.

Wang, M. C., Haertel, G., & Walberg, H. J. (1990). What influences learning? A content analysis of review literature.JournalofEducationalResearch, 84, 30-43.

Wenden, A. L. (1991).Learnerstrategiesforlearnerautonomy. London: Prentice-Hall.

Wenden, A. L. (1998). Metacognitive knowledge and language learning.AppliedLinguistics, 19, 515-537.

Wenden, A. L. (2002). Learner development in language learning.AppliedLinguistics, 23, 32-55.

Young, M. Y.C. (1997). A serial ordering of listening comprehension strategies used by advanced ESL learners in Hong Kong.AsianJournalofEnglishLanguageTeaching, 7, 35-53.

Zeng, Y. (2012).Metacognitionandself-regulatedlearning(SRL)forChineseEFLlisteningdevelopment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Zhang, L. (in press). A structural equation modeling approach to investigating test takers’ strategy use and their EFL reading test performance.AsianEFLJournal.