Making a Commitment to Strategic-Reader Training

2013-12-04STOERREIKO

. STOERREIKO

Northern Arizona University, USACalifornia State University, Sacramento, USA

Skilled readers by definition are strategic; they are able to use a repertoire of reading strategies, flexibly and in meaningful combinations, to achieve their reading comprehension goals. Thus, one of the aims of foreign and second language (L2) reading curricula should be to move students toward becoming more strategic readers. This curricular orientation can be best achieved when a strong commitment is made to strategic-reader training as a regular and consistent component of instruction across the curriculum. To explore this stance, we examine the reading strategies used by skilled readers, contrastteachingstrategieswithtrainingstrategicreaders(i.e., strategic-reader training), and examine five strategic-reader training approaches from first language contexts that can be adapted by L2 professionals to enhance the reading instruction offered in their L2 classes. The five approaches targeted for exploration include Directed Reading-Thinking Activity, Reciprocal Teaching, Transactional Strategies Instruction, Questioning the Author, and Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction. Though distinct from one another, they all acknowledge the importance of explicit explanations about strategies (or reminders about the use of select strategies), teacher modeling, scaffolded tasks, active student engagement, student practice, classroom discussions of strategy use, and the gradual release of responsibility to students who eventually decide for themselves (and/or with peers) when, where, and why to use which strategies to achieve their comprehension goals. We conclude with a discussion of the challenges, and suggestions for overcoming them, that L2 teachers and students often face in making a commitment to strategic-reader training.

Keywords: L2 reading, reading strategies, strategic readers, strategic-reader training, L1 approaches to strategy training

Correspondence should be addressed to Professor Fredricka Stoller, Northern Arizona University, PO Box 6032, Flagstaff, AZ 86011-6032, USA. Email: fredricka.stoller@nau.edu

Teaching students to be strategic means teaching them a way of thinking about what it means to be strategic, and teaching them how to adopt and use individual strategies flexibly, in combination with one another, as an integrated set with which to construct meaning (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012, p. 264).

It comes as no surprise that reading has taken on greater importance for English language learners in both second and foreign language contexts. These learners find themselves reading in English on the Web, on their smart phones, and in print, for academic, vocational, professional, and more casual, recreational purposes. To be successful readers in these varied contexts, especially in academic settings, students need to be able to, at a minimum, identify main ideas and details, distinguish between fact and opinion, draw inferences, determine author stance and bias, summarize, synthesize, and extend textual information to new tasks (e.g., class projects, oral presentations, examinations) (Grabe & Stoller, 2014).

Reading-skill mastery requires not only overarching comprehension abilities (e.g., Anderson, 2008; Grabe, 2009; Hedgcock & Ferris, 2009; Hudson, 2007; Koda, 2005; Nation, 2009) but also the development of reading fluency (e.g., Grabe, 2010; Kuhn & Schwanenflugel, 2008; Rasinski, 2010), a large vocabulary (e.g., Nation, 2008; Schmitt, 2000; Zimmerman, 2009, 2014), and a reasonably good command of grammar (Shiotsu, 2010). Furthermore, to handle the challenges of reading texts of various types and for a range of purposes, students need a repertoire of reading strategies that they can use flexibly and in meaningful combinations to achieve their reading goals (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012; Duke & Pearson, 2002). It is this latter element of the reading process, specifically reading strategies, that we focus on in this article.

It is our contention that one of the goals of second language (L2) curricula should be to move students toward becoming more strategic readers. We can achieve this goal only if we make a strong commitment to strategic-reader training as a regular and consistent component of instruction across the curriculum. To explore this stance, first we examine the reading strategies used by skilled readers. Second, we contrastteachingstrategieswithtrainingstrategicreaders(i.e., strategic-reader training) as a way to depict what commonly occurs and could occur in L2 classes with regard to strategy instruction. Then we examine five strategic-reader training approaches developed for and used in first language (L1) contexts, from which we can borrow instructional practices to enhance the reading instruction offered in our L2 classes. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the challenges, and suggestions for overcoming them, that L2 teachers and students often face in making a commitment to strategic-reader training.

INVENTORY OF READING STRATEIGES USED BY SKILLED READERS

Skilled readers, by definition, are strategic; they employ multiple strategies before, while, and after reading to achieve their reading-comprehension goals (Pressley & Harris, 2006). When they read, good readers initially apply some subset of strategies to the reading process without a lot of conscious thought. For example, with their reading goals in mind, they might preview the text; read selectively according to their goals; form, check, and revise predictions while reading; skip unknown words; and/or reread a segment of the text when they realize that they have become distracted. Moreover, they might, without deliberation, underline a key phrase, pause to create a mental image of some aspect of the text, critique the author, connect one part of the text to another, and/or reflect on what has been learned from the text. It is when their initial set of default strategies does not lead to successful comprehension that a much more intentional problem-solving mode of attention is activated (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012). At this point, good readers consciously turn to a variety of strategies (e.g., read ahead to seek clarification, reread, reconsider initial predictions, pay closer attention to discourse markers, try to unravel complex phrases) to attempt to achieve their comprehension goals. As they strive for comprehension, good readers are not only able, but also willing and motivated, to monitor the reading process and adjust their strategy use to achieve their goals (Pressley, 2002b).

Weak readers, in contrast, rarely consider their comprehension goals when reading; thus, they do not notice that attaining a reading goal might be in jeopardy, nor do they detect reading problems as strong readers do (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012; see also Grabe, 2009). Inextricably linked to their lack of attention to reading goals is that weak readers typically approach most texts in the same way. Oftentimes, especially in school settings, weak readers simply want to finish the task (i.e., get to the end of the assigned reading passage). Because weak readers are so intent on finishing the reading assignment (rather than comprehending it), they are rarely willing to slow down to attend to miscomprehension, even if it is detected (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012). Because weak readers do not typically monitor their comprehension, they do not (and possibly cannot) deliberately turn to a set of strategies for repairing faulty comprehension. The end result is poor comprehension, which, in turn, undermines their confidence, active engagement, motivation, and interest in reading. Furthermore, they do not learn to appreciate the value of reading. It is a vicious circle, indeed.

The strategies used by skilled readers—unconsciously when reading is going well and consciously when deliberate actions are required to set comprehension on the right track—are many and varied. It is not the purpose of this article to provide a comprehensive review of the literature on L1 and L2 reading strategies;①yet, it is worth noting that such a review would reveal the absence of a single agreed-upon comprehensive taxonomy of reading strategies. It is instructive, nonetheless, to introduce a few taxonomies that reveal the range of reading strategies used by skilled readers and the different ways in which they are organized by researchers.

Following the work of Mokhtari and Shoerey (2008), Grabe and Stoller (2011) categorize reading strategies as follows (see also Figure 1):

• Global reading strategies (e.g., planning and forming goals for reading, posing and answering questions, identifying main ideas)

• Monitoring reading strategies (e.g., taking steps to repair faulty comprehension, judging how well objectives are met)

• Support reading strategies (e.g., taking notes, mentally translating, synthesizing)

Global Reading StrategiesPlanning and forming goals for reading**Reading selectively according to goalsPreviewing*Forming predictions**Checking predictionsPosing questions*Answering questions*Connecting text to background knowledge*Identifying important information/main ideasPaying attention to text structure*Using discourse markers to see discourserelationshipsConnecting one part of the text to anotherMaking inferencesCreating mental images*Guessing meaning from contextSummarizing*Critiquing the author, the text, feelingsabout the textMonitoring Reading StrategiesMonitoring main idea comprehension*Identifying reading difficultiesTaking steps to repair faulty comprehension(e.g., rereading, looking forward orbackward, checking illustrations, pausing andposing questions, pausing to subvocalize mainidea, considering prior knowledge)Judging how well objectives are metRereading**Reflecting on what has been learned from thetextSupport Reading StrategiesUsing the dictionaryTaking notes**Paraphrasing**Translating (mentally)**Underlining or highlightingUsing graphic organizersSynthesizing

Figure1 Reading Strategies (adapted from Grabe & Stoller, 2011, p. 226)

Note: Overarching categories adapted from Mokhtari and Sheorey (2008); Shaded boxes indicate strategies deemed worthy of instruction because they improve reading comprehension (Duke, Pearson, Strachan, & Billman, 2011); Empirically validated reading strategies indicated with a single asterisk; Reading strategies indirectly supported by validated multiple-strategy instruction identified by a double asterisk.

Of particular interest in Figure 1 are the reading strategies that have been empirically validated (indicated with a single asterisk), the reading strategies that are indirectly supported by validated multiple-strategy instruction (signaled with a double asterisk), and the reading strategies deemed especially worthy of explicit instruction (placed in shaded boxes) because they have been shown to improve reading comprehension (see Duke, Pearson, Strachan, & Billman, 2011).

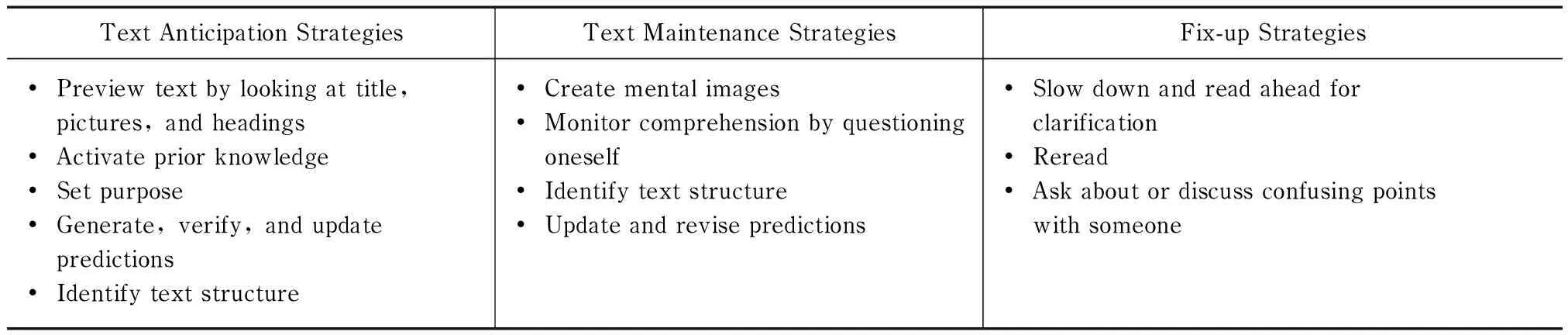

Almasi and Fullerton (2012) categorize a different, though at times overlapping, set of reading strategies into three strategy types, specifically text anticipation strategies, text maintenance strategies, and fix-up (repair) strategies, as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1 Three Strategy Clusters, Introduced in Almasi and Fullerton (2012)

Despite the differences between these reading-strategy taxonomies (and others discussed in the literature), “the research has been unequivocally clear that providing explicit instruction about strategies helps students learn to process text strategically” (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012, p. 6; see also Ferris & Hedgcock, 2009; cf. Wilkinson & Son, 2011). Reading researchers also agree upon other findings about skilled readers, developing readers, strategic-reader training, and reading teachers that are worth mentioning here:

• Skilled readers use strategies flexibly and in meaningful combinations (rather than individually) to achieve their reading goals. Examples of meaningful strategy combinations include (a) previewing followed by forming goals for reading; (b) predicting followed by checking predictions and revising them with reading goals in mind; (c) slowing down to reread followed by reading ahead, subvocalizing a main idea, and/or considering prior knowledge in relation to current text content.

• Many combinations of strategies that skilled readers use become automatic, but only after repeated use, practice, and success.

• Developing readers benefit from explicit strategic-reader training that is consistent, extends over a long period of time, and is addressed across the curriculum.

• Developing readers benefit from explicit discussions aboutwhichstrategies to use, when and where to use them, and what is gained from using them (i.e.,whyto use them).

• It takes a long time and a lot of purposeful reading for readers to become strategic.

• It takes a long time for teachers, too, to become effective teachers of strategic-reading processing. Such instruction requires that teachers understand reading processes, embrace new ways of thinking about the teacher’s role in the reading classroom, and make use of a repertoire of instructional practices that become regular classroom features.

These findings, including the taxonomies of strategies used by strategic readers (such as those presented in Figures 1 and 2), provide valuable guidance for L2 teachers, material writers, and curriculum designers. They give us an excellent point of departure for (a) rethinking our reading instruction and the expectations that we have of ourselves and our students, (b) revising course and curricular goals, (c) planning our classes, and (d) developing instructional support materials. They also raise a question worth pondering: What are the most effective ways to integrate combinations of strategies into our instruction and commit to strategic-reader training? This is the critical question that we attempt to answer in the following sections.

TEACHING STRATEGIES VERSUS TRAINING STRATEGIC READERS

The good news from research on (a) strong and weak readers and (b) the strategies that they use (or do not use) is that less-skilled readers can develop the habits of strategic readers when their teachers, and the programs in which they teach, make long-term commitments to explicit strategic-reader training (Grabe, 2009). Such training has been shown to improve students’ comprehension of both simple and more elaborate texts, bring about changes in students’ strategy use, and improve students’ attitudes toward reading (e.g., Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2008). Unfortunately, few L2 programs make a strong across-the-curriculum commitment to training strategic readers, even though most L2 practitioners would agree, in the abstract, that reading strategies are important (see e.g., Zhang, 2008). In the subsections that follow, we contrast how reading strategies are typically addressed in L2 classes and how they could be addressed with more emphases placed on strategic-reader training.

TeachingStrategies

L2 reading is taught in diverse instructional contexts, with students of different ages, varied L1 backgrounds, and a range of motivational levels. Despite this variation, it is probably safe to say that L2 programs typically address reading-skill development in discrete reading-skill classes, in integrated-skill (commonly reading and writing) classes, and/or in content-based classes (with a dual commitment to language and content learning). How reading strategies are addressed in these different types of L2 classrooms cannot be captured in one single “snapshot” of the L2 reading classroom. Yet an examination of numerous L2 reading textbooks permits some generalizations to be made:

• In many L2 classes, reading strategies are taught independently from one another. We often see textbook chapters that address one strategy at a time, in stand-alone sections with headings such as skimming, scanning, inferencing, previewing, and guessing words from context. Sometimes the tasks in these sections are decontextualized, that is, they are not actually tied to the central reading passage in the chapter, thus, rarely are they linked to students’ immediate reading-comprehension goals.

• It is not often that L2 students are asked to articulate reading-comprehension goals.

• Rarely are strategies introduced in meaningful combinations to model skilled-reader practices.

• Sometimes reading strategies are indirectly addressed in pre- and post-reading textbook tasks. It is not uncommon to find pre-reading tasks at the beginning of textbook chapters that encourage students to connect the chapter topic to their background knowledge, preview the reading passage, and possibly predict its contents. Immediately following textbook reading passages, we typically find comprehension questions that require students to identify main ideas, distinguish them from details, make inferences, and/or critique feelings about the text. Pre- and post-reading tasks such as these could serve as starting points for discussions of reading strategies, but rarely do. Furthermore, in L2 classrooms, post-reading tasks are typically used toassess, rather thanteach, comprehension (see Anderson, 2008).

• Rarely, in L2 textbooks, are students asked or taught to use during-reading (sometimes called while-reading) strategies that could facilitate comprehension and guide students in, for instance, constructing meaning, evaluating what is being read, building text-structure awareness, dealing with miscomprehension and/or difficult passages, and guessing words from context (see Grabe & Stoller, 2011). Instead, what we see most often are directions to “Read the passage.”

• Almost never do L2 textbooks explicitly guide students in a consideration ofwhatstrategies they have used,howthey used them,whenthey used them, orwhythey used them.

These observations suggest that the common L2 reading textbook (and classroom) lends itself to an emphasis on individual stand-alone strategies rather than on students who need to become strategic readers. Thus, instead of training strategic readers, the goal, if there is one, is to introduce students to discrete reading strategies. Sadly, few L2 programs make a strong commitment to explicit strategic-reader training as a central component of not only reading classes but also the reading curriculum (cf. Janzen, 1996, 2001; Klingner & Vaughn, 2000, 2004; Klinger,etal.).

TrainingStrategicReaders

Discussions of strategic-reader training are much more common in the L1 literature than the L2 literature (e.g., Almasi & Fullerton, 2012; Pressley, 2006). In L1 explorations of the topic, strategic-reader training is portrayed as an instructional component that is central to reading curricula, rather than peripheral and only incorporated into instruction when there happens to be some extra class time. When instruction focuses on strategic-reader training, rather than on the teaching of discrete, stand-alone strategies, instruction centers around purposeful reading during which text comprehension is the goal. Furthermore, strategic-reader training aims to teach students to use multiple strategies flexibly and in combination. The ultimate goal is to train strategic readers who know when, how, and why to use which strategy combinations to regulate their comprehension (Baker, 2002). Such an understanding develops through classroom discussions about strategy use, repeated observations of good readers (e.g., the teacher or peers) using various strategies effectively, extensive practice using multiple strategies in and out of class, and an appreciation for the value of reading. To assist students in reaching this point, strategic-reader training involves deliberate scaffolding that begins with explicit teacher explanations of strategy use (and the benefits of it), teacher modeling, student practice (with the teacher observing, responding to, and reinforcing students’ strategy use), and then the gradual release of responsibility to students who eventually decide for themselves (and/or with peers) when, where, and why to use which strategies to achieve their comprehension goals. In this way, the teacher moves students toward becoming successful independent, self-regulated readers (Baker, 2002).

Multiple-StrategyInstructionalApproaches

Compared to strategic-reader training in L1 settings, very few L2 practitioners have devoted the time or energy to develop systematic approaches to L2 strategic-reader training. Though we have gradually seen more attention paid to such training in the field (e.g., Anderson, 2008, 2009; Grabe, 2009; Janzen, 1996, 2001; Klingner & Vaughn, 2000, 2004; Klinger,etal., & Swanson, 2012; Pritchard, 2004), this orientation does not run across our textbooks (nor the training conducted in most of our teacher-preparation programs). In this section, therefore, we turn to five instructional approaches developed for L1 readers (i.e., Directed Reading-Thinking Activity, Reciprocal Teaching, Transactional Strategies Instruction, Questioning the Author, and Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction) as a way to showcase practices that L2 practitioners can adapt to enhance the reading instruction that takes place in their L2 classes.

The five approaches described in the sections that follow were originally developed for L1 readers at primary and/or middle-school levels. They are uniquely distinct from one another, but share the following features (with some variations):

• Students are trained to use multiple strategies. Teachers may initially introduce just one strategy (or a small number of strategies) at a time. Yet the goal of instruction is for students to become able to use a range of strategies flexibly so that their strategy choices complement the texts that they are reading and their reading goals. Thus, students are constantly guided and reminded to practice target strategies with other strategies (that perhaps they are already familiar with).

• Students discuss and practice strategies while actively seeking and building meanings from the texts that they are reading. Understanding what they are reading is the primary focus of teaching and practicing strategies. The teaching of strategies, thus, is highly contextualized, central to the teaching of reading, and focused on comprehension.

• Strategies build upon what we know about how skilled readers read. For example, the teacher uses herself as an example of a “good” reader and models skilled-reader practices for students to follow.

• Students are trained to use strategies during all stages of reading—before, during, and after reading. Oftentimes, the use of strategies is connected across stages. For instance, student’s confirmation, fine-tuning, and/or rejection of predictionsduringreading could be triggered by the previewing and predicting that students engage inbeforereading.

• As a result of instruction, students learn what strategies to use, when, how, and why. To meet this instructional goal, the teacher provides explicit explanations about strategies (or reminders about the use of select strategies), models their use, and creates ample opportunities for students to practice strategies in and out of class. Students receive assistance from the teacher (and often peers) initially when using strategies, but they are expected to eventually increase their independent use of strategies when reading alone.

• Reading collaboratively is highly valued. Every reader approaches a piece of text differently. By reading and discussing texts with peers and the teacher, students can not only solve their comprehension problems but learn that texts often result in multiple interpretations.

Despite these similarities, each of the five approaches has features that distinguish it from the others. In the sections that follow, we introduce each approach and highlight its distinct characteristics. (Readers of this article who desire more detailed descriptions of these approaches, including their origins and research conducted on their effectiveness, should seek out the publications cited in this article to get started.) Each description is followed by suggestions for how L2 teachers might adapt ideas from the approach to assist L2 readers in becoming more strategic. Although few of our suggestions have yet to be empirically tested in L2 settings, we believe that they are logical extensions of the L1 approaches and worthy of piloting and further investigation in L2 classrooms.

DirectedReading-ThinkingActivity

Directed Reading-Thinking Activity (DR-TA) is an instructional approach in which students develop strategic reading abilities similar to the abilities needed forproblem-solving. In DR-TA, students first make predictions about upcoming text, using the information available to them. This information could come from the text itself (e.g., the title, an illustration, an opening paragraph of the text) or from students’ background knowledge. Making predictions at set stopping points in the text is a key step in DR-TA. The “simple” act of generating predictions, which are meant to be confirmed, rejected, or modified while reading, helps students establish goals that guide their subsequent reading. After reading, students evaluate how well their predictions were (or were not) met, while discussing their understanding of the text. Students then make the next set of predictions. This cycle (see Figure 2), repeated until students finish reading the entire passage, leads to the development of students’ (a) monitoring abilities (as a result of predicting practice) and (b) main-idea comprehension and text-evaluation abilities (as a result of discussions of predictions).

Figure 2 Key Procedures Followed in

In DR-TA, reading is thought to resemble problem-solving patterns (e.g., Davidson & Wilkerson, 1988; Stahl, 2008) that involve the generation of hypotheses, the testing of hypotheses, and the acceptance or rejection of the original hypotheses (Smith, 1975, cited in Davidson & Wilkerson, 1988). This pattern of generating, testing, and refining original hypotheses parallels what students do in DR-TA: (a) generating predictions before they read, (b) confirming, rejecting, or revising predictions during reading, and then (c) evaluating predictions after reading.

Another important characteristic of DR-TA is students’ active involvement in the process of reading through peer collaboration. In DR-TA, students take initiative in comprehending text, while the teacher plays the role of facilitator. Instead of teacher-led discussions, students work in small groups. Students are expected to remain open-minded about alternative interpretations of the text, contribute their own points of views, and learn from each other. All group members take part in making predictions. Because students’ predictions guide the actual reading that follows, the goals for reading are set by the students themselves. Students’ predictions also shape their post-reading discussions. Thus, in DR-TA, it is students who play the central role in determining how they build text comprehension.

L2ClassroomApplications

DR-TA, originally developed for school-age L1 readers, was introduced over two decades ago to teachers as a useful means to assist L2 readers (e.g., Dixon & Nessel, 1992). L2 teachers can use the steps illustrated in Figure 2 with texts from a wide range of genres. In this way, students learn that certain types of texts—stories, poems, and other literary works, in contrast to news reports, chapters from science textbooks, and other expository texts—allow for more flexible predictions and interpretations. When students work with peers to make predictions, it is important that the teacher remind them to refer to textual clues (e.g., title, illustrations, headings, etc.) and/or their background knowledge, rather than rely on random intuitions or guessing. Guiding students to refer to information presented in the text when they discuss the effectiveness of their predictions after reading is a crucial element of the approach.

Through DR-TA, L2 students learn how forming predictions, setting a purpose for reading, and monitoring comprehension are connected with one another. DR-TA also naturally triggers students’ use of other strategies such as previewing, rereading, and activating background knowledge; for example, because students are asked to refer back to the text to discuss the text and their predictions, they constantly reread the text. Additionally, DR-TA can broaden L2 students’ views toward reading. DR-TA places more responsibility on students to develop understanding of the text. Because many L2 learners are accustomed to teacher-centered reading instruction, it may initially be uncomfortable for them to determine their own goals for reading and rely on themselves (not the teacher) to construct text meaning. Yet, the incorporation of DR-TA into the L2 classroom can help students realize that active involvement in the reading process is essential to make their reading experience meaningful.

ReciprocalTeaching

Reciprocal teaching (RT) is an instructional procedure in which students are trained to skillfully use four strategies: predicting, questioning, clarifying, and summarizing (e.g., Oczkus, 2010; Palincsar & Brown, 1984). Developed for L1 readers in the U.S., RT has been adopted largely in elementary and secondary school settings, both in and outside the U.S. (e.g., Spörer, Brunstein, & Kiescheke, 2009; Takala, 2006). Similar to DR-TA, in RT, students learn to make relevant predictions about upcoming information in the text, using clues in, for instance, the title, headings, illustrations, and other graphics (e.g., maps, captions, and tables). In addition to predicting, students practice forming their own questions about the text, with the aim of helping them identify main ideas in the text. Students also learn various ways to clarify text content when they encounter comprehension difficulties; these clarification strategies include using background knowledge, rereading the text, and looking for familiar word parts. Lastly, students practice forming summaries, thereby focusing on main ideas and important details.

The four strategies emphasized in RT are first explained and modeled by the teacher, who initially assumes the role of the “leader” in strategies training. Soon, though, the teacher hands over the role of the “leader” to the students. Students then form small groups and take turns modeling—for their peers—how to apply the four strategies, while discussing the content of the text that they are reading. In other words, students are asked to “teach” (their peers) how to comprehend the text (thus, the “reciprocal teaching” designation). The teacher assists students when needed, but the teacher’s guidance diminishes as students become increasingly more comfortable applying the strategies themselves.

Like DR-TA, a key feature of RT is student collaboration. Students work together to build rich dialogues around the text, using the four target strategies for this purpose (see Figure 3). RT assumes that reading is a process that requires readers’ active search for meaning in the text (Allen, 2003). By working in small groups and taking turns leading conversations around the text, students become more involved in the reading process. While using the four strategies, students share their understanding of the text, listen and respond to their peers’ thoughts and questions, and adjust their understanding of the text accordingly.

Figure 3 Four Core Strategies Focused

L2ClassroomApplications

The procedures used in RT can be effectively adapted for L2 classrooms, with the goal of demonstrating how a particular set of strategies can work together to promote comprehension. The teacher can first introduce students to the four target strategies—predicting, questioning, clarifying, and summarizing—and model their use. Using the teacher’s modeling as a guide, L2 students can then read a portion of the text silently and work in groups, with a student dialogue leader posing questions (similar to those that might be asked by the teacher) about the main ideas in the text. The student leader can guide the group in forming a summary of the passage—perhaps in writing, not just orally—while also helping the group clarify any difficulties that were encountered in the text. Before moving on to the next portion of the text, the leader can take the initiative to make predictions about what is likely to follow. Students then read the next portion of the text, and another student takes over the role of the dialogue leader. (See Palincsar & Brown, 1984, for similar procedures used with L1 readers.)

The procedures used in RT can provide L2 students with opportunities to experience multiple-strategies instruction, without overwhelming them by the number of strategies that they could possibly use as skilled L2 readers. In RT, students are not expected to master the entire range of comprehension strategies used by skilled readers (e.g., see Figure 1). Rather, they are guided in learning how to use four specific strategies effectively. This focused approach allows students to have ample time to learn about and practice the target strategies, within the limited instructional time available to them. We need to remember, though, that these four “core” strategies prompt students’ use of other useful reading strategies. For example, when students engage in discussions to clarify information in the text, they often reread the text, connect parts of the text, create mental images, make use of discourse markers, and so forth. Thus, RT does not really limit students’ learning to the four target strategies; rather, it has the potential to develop students’ ability to use multiple strategies flexibly.

Because RT centers on student-group discussions, not whole-class discussions, in L2 settings where students might feel uncomfortable speaking and/or have weak speaking skills, the teacher might need to adapt the RT approach. L2 teachers might find it useful to introduce conversational gambits that facilitate student-student exchanges (e.g., gambits for asking for clarification, requesting repetition, introducing new viewpoints) and engage students in role plays to practice them. In L2 instructional settings where students are not accustomed to working in groups or listening to classmates, the teacher may need to “socialize” students to the approach so that they see its value and willingly give it a try. In foreign language settings where the majority of students share the same L1, it is assumed that teachers will do their best to encourage students to speak in the L2 during discussions about text and strategy use.

TransactionalStrategiesInstruction

Transactional Strategies Instruction (TSI) is an instructional approach in which students are trained to use various strategies while actively discussing their understanding of the text (e.g., Allen, 2003; Brown, 2008). In TSI, the teacher regularly reminds students that they can learn from the practices of good readers, one of the key principles of the approach. To demonstrate skilled-reader habits, the teacher often plays the role of “the good reader” to demonstrate what she would do to comprehend text. Techniques such as thethinkaloud(i.e., verbalizing one’s thinking while reading) are used for this purpose. Equally important is students’ active interaction with not only the text but also other readers—their peers and the teacher—during which they exchange their understanding of the text. In TSI, it is important that the teacher provide direct explanations of the purpose(s), benefits, and times to use various strategies. These vital components, that is, the teaching and practicing of strategies, are integrated into discussions about text content. While students and the teacher read and discuss the text, they jointly decide which strategies to use to help them better understand the text. Initially, of course, it is the teacher who plays the major role in deciding which strategies to use; the teacher introduces appropriate strategies, explains and demonstrates how they work, and provides students with guided practice. Yet, students are soon asked to choose appropriate strategies themselves, first collaboratively with their peers, and eventually alone. Students who have experienced TSI have shown improved text comprehension abilities and strategy use, as well as better perceptions of themselves as readers (e.g., Allen, 2003; Brown, 2008).

Compared to DR-TA and RT, the strategies taught in TSI are more flexibly chosen. TSI does not have a pre-determined set of strategies to be taught. Rather, the strategies taught in TSI depend on the text being read and how students comprehend (or fail to comprehend) it. The strategies commonly taught in TSI (see Allen, 2003; Brown, 2008) include

• Clarifying unfamiliar words and confusing content

• Connecting prior knowledge to text

• Constructing images

• Generating questions

• Making predictions

• Rereading

• Summarizing

• Thinking aloud

TSI teachers, from the early stages of such instruction, encourage students to use multiple strategies together (e.g., Pressley, 2002a). Thus, when the teacher introduces a new strategy, she models it in concert with other strategies that the students have already learned (or been introduced to). For example, when introducing the strategy of making predictions, she may link it to the use of previously introduced and/or practiced strategies such as connecting text to prior knowledge, previewing, and/or constructing images. TSI, like most approaches to strategic-reader training, assumes that it takes a long time for students to master the coordinated use of strategies; thus, TSI training lasts months if not years.

L2ClassroomApplications

TSI provides L2 teachers with valuable insights about successful strategic-reader training, including the need for teaching and practicing strategies in context, giving students abundant opportunities to read collaboratively, and emphasizing the coordinated use of multiple strategies. To incorporate these elements of the approach into their classrooms, L2 teachers can start with any text that their students are interested in reading or assigned to read. Because TSI does not specify a pre-determined set of strategies to be taught, the teacher introduces students to those strategies that are well-suited to the text and likely needed for text comprehension. While doing so, the teacher reminds students of previously taught strategies that also work well with the particular text being read. For example, with informational texts, summarizing may be a good strategy for the teacher to introduce and guide students in practicing. At the same time, the teacher can remind students that other previously learned strategies, such as rereading and using graphic organizers, can work well in combination with summarizing. Because strategies are explicitly explained, modeled, and practiced in connection with the text that students are reading, students are likely to see the relevance of learning the strategies to become effective L2 readers.

Reading collaboratively is also a key aspect of TSI. L2 teachers can use whole-class discussions, small- group activities, and pair work to create abundant opportunities for students to exchange their understanding of and responses to the text. Discussions around text encourage students to activate their strategic reading through, for instance, rereading the text, connecting their background knowledge to the text, and summarizing text content. As in the case with DR-TA and RT, sharing personal thoughts about and understanding of the text may initially lead to some discomfort among L2 students. Yet, exchanging individual ideas about the text should be promoted as an excellent means to resolve comprehension difficulties and misunderstandings, as well as to open up students’ eyes to different interpretations of the text.

To facilitate students’ coordinated use of multiple strategies, L2 teachers could perhaps design activities that raise students’ awareness about the fact that strategies should be used in combination, not in isolation. For example, students can be asked to keep areadingstrategieslogin which they record the strategies that they use for each reading assigned as homework. After logging their strategy use for a while, students can bring their logs to class and discuss how their orchestrated use of strategies has helped them read more effectively and what they need to do to improve their strategy use. An assignment like this gives students a chance to keep track of their own progress as strategic readers; simultaneously, the teacher has the opportunity to note strategies that students seem to have mastered and those that need further explanation, modeling, and practice.

QuestioningtheAuthor

Questioning the Author (QtA) is an instructional approach that encourages students’ active engagement with text meaning (e.g., Beck & McKeown, 2006). Though the three approaches introduced earlier (i.e., DR-TA, RT, and TSI) also emphasize student engagement with text, QtA is unique in that it regards authors of texts as imperfect. QtA assumes that readers need to take some initiative to make sense of ideas presented in the text because authors do not always deliver their ideas clearly or completely in their writing. Thus, in this approach, students are trained to question the invisible author while reading, and then seek answers to their questions in the text as a way to promote discussions around text comprehension.

The heart of QtA is its use ofqueries, that is, general probes used to initiate class discussions around the meaning of text (Beck & McKeown, 2006). In QtA, the teacher reads aloud a small segment of text, one segment at a time, and posesqueriessuch asWhatistheauthortalkingabout?Whatdoestheauthorwantustoknow?That’swhattheauthorsaid,butwhatdidtheauthormean?Doesthatmakesensegivenwhattheauthortoldusbefore?Whereinthetextcouldtheauthorexplainhimselfbetter? AndWhydoestheauthortellusthisnow? As these examples show, such queries typically require students to go beyond simply extracting textual information (e.g., “What happened to him next?”). When answering queries such as “What does the author mean?”, students actively connect information from various parts of the text, supplement missing information using their background knowledge, build upon what their peers have said, and so forth, to comprehend the text. Thus, the discussion of queries, central to this instructional approach, is what leads to deeper text comprehension. These discussions typically take place with teacher guidance, though the goal of the approach is to develop students’ ability to gradually use such critical reading skills on their own. Students who have experienced QtA have reported that they came to regard reading as more aboutunderstandingthe text than simply extracting factual information from it (Beck & McKeown, 2001). Interestingly, McKeown, Beck, and Blake (2009) report that students who receive QtA training demonstrate better text recall than not only students who receive more traditional reading instruction, but also those who engage in other forms of multiple-strategy instruction.

L2ClassroomApplications

Though QtA was originally developed for L1 elementary school children, the principles underlying this approach can be used successfully with L2 students as an effectiveduring-readingactivity. During reading, L2 students are likely to encounter portions of text that are unclear to them, for various reasons (e.g., lack of vocabulary, absence of relevant background knowledge, grammatical complexity, length of sentences). QtA can provide students with strategies to overcome such comprehension difficulties and develop a solid understanding of the text. In preparation for class, the teacher reviews the text to locate text segments where students may face comprehension problems or where providing students with further explanations might be beneficial. Then, while students are reading the text, the teacher poses queries, focusing on areas where it is crucial for students to comprehend the text. With L2 students, it may work well if the teacher identifies stopping points in advance, asks students to read the target portion of the text silently, and then poses queries. Eventually, the teacher can ask students to generate queries themselves. Perhaps, similar to the steps followed in RT, students could be placed in small groups to take turns posing queries for their peers to respond to. In this way, students can not only build understanding of text collaboratively but also discuss the effectiveness of each other’s queries.

QtA provides excellent opportunities for L2 students to develop their abilities to read L2 text strategically and critically. Though queries used in QtA may look somewhat familiar to L2 teachers, the discussion of the queries is what leads to strategic-reading practices. When queries are followed by questions such as “How do you know?”, “Where does this occur?”, or “What do you mean?”, students return to the text and defend their answers with actual text information (when available). Thus, QtA naturally prompts students’ use of multiple strategies such as rereading, inferencing, connecting to background knowledge, looking for clues (e.g., discourse markers), critiquing the author, and many of the other strategies listed in Figure 1. Additionally, the QtA approach encourages students to look for strengths and weaknesses in the author’s writing. Becoming aware that a piece of writing can have weaknesses helps students become more attentive when they read. For example, instead of simply accepting the information presented in the text, students become more willing to examine how pieces of information fit together, what the author is not telling readers, and why. Being aware that they may encounter unclear text at any time can strengthen students’ self-monitoring skills. Though the idea of “questioning” the author may be new to L2 learners who are used to regarding authors as authoritative figures, critically approaching a piece of writing is an essential skill for good readers. After all, no writing is perfect, and skilled readers pose questions and seek answers to questions as they strive to meet their comprehension goals.

Concept-OrientedReadingInstruction

Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI) is a curricular framework that tightly interweaves the learning of a particular content area (e.g., science) with (a) the development of reading skills and strategies and (b) active student engagement (e.g., Guthrie, Wigfield, & Parencevich, 2004; Swan, 2003). CORI was originally developed for L1 readers in the elementary school setting, though it has been adopted for middle-school students as well (e.g., Guthrie, Klauda, & Ho, 2013). In CORI, students first identify their own questions related to the overarching conceptual theme (e.g., weather) through observational and hands-on activities. Next, students seek answers to their questions by locating and reading multiple texts, taking notes, and meaningfully integrating information. During such activities, students discuss, learn, and practice how to use multiple strategies—in various combinations—to successfully learn from the text. Students then share the answers to their questions with their peers.

Through these instructional stages, CORI aims to facilitate reading engagement. CORI recognizes that engaged readers are intrinsically motivated; such readers choose to read because they wish to know more about the topic, not because of external rewards such as good grades or teacher recognition. Also, engaged readers effectively use what Guthrie and his colleagues call “cognitive strategies,” such as activating background knowledge, searching for information, using graphics to organize information, and posing questions (Guthrie & Taboata, 2004). In CORI, students’ intrinsic motivation for reading and their ability to use strategies are essential for the successful learning of target content. The positive effects of CORI on students’ reading motivation, strategy use, and reading achievement have been repeatedly reported in the literature (e.g., Guthrie, Klauda, & Ho, 2013; Guthrieetal., 2009; Wigfieldetal., 2008).

Comprehension strategies introduced in CORI (Guthrie & Taboata, 2004; Swan, 2003) include—but are not limited to—the following:

• Activate background knowledge

• Form and answer questions

• Identify main ideas

• Monitor comprehension and repair faulty

comprehension

• Organize information graphically

• Paraphrase

• Pay attention to text structure to aid

comprehension

• Summarize

• Synthesize

• Take notes

In CORI classrooms, these strategies are taught and practiced in several stages: (a) explanation of the strategy, (b) teacher modeling and scaffolding, (c) guided practice, and (d) independent practice (Guthrie & Taboata, 2004; cf. Duke & Pearson, 2002, who advocate a five-stage model of comprehension instruction). It is worth noting that the four stages advocated by Guthrie and Taboata (2004) are not that different from those that emerge from the other approaches introduced earlier. The difference, here, is that CORI proponents articulate these stages clearly in their descriptions of the approach. In CORI, the teacher first provides a brief explanation of the target strategy (e.g., activating background knowledge). The teacher then demonstrates how and why she uses the strategy, using a relatively short text on a topic that students are already familiar with. This teacher modeling can be followed by a scaffolding activity during which the teacher and students use the strategy together, perhaps using a new portion of the text. As students become familiar with the strategy, the teacher asks students to practice the strategies themselves, but with teacher support, using a range of texts. At this stage, as Swan (2003) suggests, the teacher can ask students to work in pairs. Eventually, though, students are expected to practice the strategies on their own, using their knowledge ofwhichstrategies should be usedwhen,how, andwhy(see Figure 4).

Figure 4 Four Stages of Strategies Training in Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI)

L2ClassroomApplications

Though CORI originated as an L1 instructional framework, the concepts of reading engagement and strategies instruction that underlie CORI have been introduced to L2 practitioners (e.g., Freeman & Freeman, 2009; Grabe, 2009; Stoller, 2004). The CORI approach can be applied particularly well in L2 content-based classrooms. In content-based instruction (CBI), students use their L2 to study a particular content area (e.g., U.S. history); the goal of CBI is to develop both students’ overall L2 proficiency and their content knowledge (Snow, 2014). CBI, by its very definition, encourages students to read multiple texts related to a specific content area, which is similar to what students do in CORI. CBI teachers, therefore, can adopt or adapt the strategies instruction proposed in CORI to develop L2 students’ reading strategies as a way to help them learn from multiple related L2 texts. For example, let’s say that the teacher selects American Culture as the target content area. Students can generate their own questions related to the content, while the teacher chooses the main text(s) on American Culture that all students are required to read. The teacher uses the main text to introduce, model, and guide the use of appropriate comprehension strategies. Students then practice using these strategies, while reading additional related texts, selected by the teacher and/or the students themselves. Because students read multiple texts to search for, locate, and integrate gathered information to answer their questions, they would have ample opportunities to practice the strategies that they have been introduced to. Students can then create a PowerPoint or poster presentation to share their findings with their peers.

Strategies instruction, adapted from CORI for the L2 classroom, serves as an excellent reminder that the purpose of studying the L2 is to become able to use it. The process of posing and answering questions of one’s own interest gives students a real purpose for reading L2 texts and authentic opportunities for practicing strategies that help them better comprehend L2 texts. Additionally, this process highly resembles the process ofdoingresearch, which should be particularly helpful if students are interested in using English for academic purposes. Conducting a small-scale research project is a common assignment in English-medium secondary and higher education classrooms. Strategies instruction that is integrated into a research-project assignment prepares L2 students for success in mainstream classes.

In L2 classrooms with an orientation other than CBI, L2 teachers can take advantage of textbook units to implement the strategies instruction proposed in CORI. Textbooks—especially those written for intermediate and advanced L2 students—often include a small set of related readings that form the basis of a thematic unit (e.g., population change and its impact, in McEntire & Williams, 2009). A teacher who uses such a textbook can ask students to pose a question related to the theme, read textbook reading selections (and possibly other texts found by students) to answer the question, and write a report to share their answers with peers. Through such an assignment, students can deepen their knowledge of the theme, while learning and practicing strategies such as forming and answering questions, identifying main ideas, taking notes, organizing information graphically, paraphrasing, summarizing, and synthesizing. In this way, students witness first hand how strategic reading can help them effectively learn from reading.

InsightsGainedfromFiveL1Approaches

The five L1 approaches introduced in this article are potentially beneficial for L2 readers. Unlike the ways in which reading strategies are typically addressed in L2 classrooms, these L1 approaches are consistent with the characteristics ofstrategic-readertraining. They commit to (a) repertoires of strategies; (b) strategy use in the context of real-time reading; (c) explicit explanations and discussions ofwhen,how, andwhyto usewhichstrategies; (d) teacher modeling and scaffolding; (e) many practice opportunities; and (f) active, engaged readers. They teach students comprehension routines that lead to the development of a repertoire of strategies that can be used flexibly. The ultimate goal of these approaches is students’ independent use of strategies and, of course, text comprehension.

These approaches provide L2 teachers with sets of instructional practices that can be adapted, in various ways and combinations, depending on the needs of their students. In all cases, L2 teachers need to keep in mind that training strategic readers requires substantial time and dedication from students, teachers, and the programs in which they find themselves. The incorporation of strategic-reader training into L2 classrooms requires that the teacher make notable changes in standard L2 pedagogical routines and do so for an extended period of time. Consider DR-TA, which dramatically changes standard classroom practices. With DR-TA, the teacher no longer dominates classroom discussions about texts; rather, students’ predictions shape the focus of reading and post-reading discussions.

We are aware of the fact that many—if not most—L2 teachers do not have the freedom and/or support to make substantial changes to their instructional practices, at least immediately. Additionally, in some cases, teachers may not feel ready to demonstrate flexible L2 reading-strategy use due to their lack of awareness, practice in modeling, or even confidence. We think, though, that L2 teachers who have limited time and/or freedom to implement substantive instructional changes in their classrooms can still borrow practices from these L1 approaches to help their students develop strategic-reading habits. Perhaps the key is to start with small incremental steps by, for instance, focusing on select aspects of a single approach (or combining select aspects of two or more approaches). For example, an L2 teacher who feels that DR-TA might be advantageous to her students can systematically incorporate the routine of making predictions and then reading to check the accuracy of those predictions into her instruction, without the extensive peer discussions typically associated with DR-TA. In place of peer discussions, the teacher could conduct a short debriefing session with the entire class and students could individually record their experiences making predictions in their journals. As another example, consider the teacher who finds aspects of TSI particularly useful, but feels uncertain about the time it might take to select text-appropriate strategies with students. That teacher could build upon ideas from RT and start with only four (main) strategies, rather than follow the more open-ended TSI approach. These examples illustrate that while the partial implementation of principles underlying the five L1 approaches may not produce the same learning outcomes as their full implementation, the incorporation of select strategic-reader training practices could help L2 students take their first steps toward becoming strategic readers.

CONCLUSION

Considering how important reading is for L2 students, it behooves us all to rethink our commitment to strategic-reader training, not only in our individual classes and in the materials that we adopt and adapt for classroom use, but also across the L2 curriculum. Instead of focusing our attention onassessingstudents’ reading comprehension, as we are apt to do, we ought to switch our emphases toteachingstudents how to comprehend. We can do this, in part, by making a commitment to training strategic readers who use multiple strategies flexibly and in combination while reading to achieve real reading goals.

As straightforward as it is to advocate this stance, we realize that it might not be easy to make the changes required for a strategic-reader orientation in our classes and the programs in which we teach. Like all teaching innovations, a commitment to strategic-reader training requires not only changes in visible teaching practices, but also changes in our thinking and beliefs about reading, reading instruction, our daily lessons, and teacher and student roles (e.g., El-Dinary, 2002; Wilkinson & Son, 2011). There is plenty of evidence in the L1 research that points to the time required to transform oneself into an effective trainer of strategic-reading processes (Wilkinson & Son, 2011). Furthermore, teachers often feel that existing curricula prevent them from making the time commitment needed for effective strategic-reader training. Sometimes teachers find it difficult to turn over responsibility to their students; nor are they accustomed to engaging students actively in the decision-making processes characteristic of skilled readers. Moreover, effective strategy training requires that teachers engage in instantaneous decision making as they observe and guide the strategic (or non-strategic) actions of students (Almasi & Fullerton, 2012). For new teachers or overworked teachers, who are grappling with classroom management, standards, pacing, and large classes, to name just a few of the challenges that they may face, such instantaneous responses, which cannot be planned ahead of time, are challenging. Sometimes reading teachers feel as if they are fighting an uphill battle because they are the only teachers required to address strategic-reader training, thus their efforts are not being reinforced by other teachers.

Teachers are also faced with students who do not buy into the value of strategic-reader training, in part because the approach challenges their beliefs about reading, reading lessons, teacher-student roles, and group work. Students are often socialized to view school success as having completed a reading assignment rather than comprehending it. It is hard to move away from this task-completion orientation. Moreover, some students are reticent to participate in the all-important which-when-how-why discussions that are integral to strategic-reader training.

Despite these challenges, there is plentiful evidence to suggest that we should rethink our approaches to reading instruction. A focus on the strategic reader seems to be worth the effort. When students learn to appreciate the value of reading strategies and being strategic, they will likely work more diligently to become strategic. When that happens, our students will become more successful, motivated, interested, and self-regulated readers. To help make this happen, we close our discussion of strategic-reader training with some practical suggestions:

• Make strategic-reader training a part of every single class.

• Embed strategic-reader training into real reading activities where comprehension is the goal.

• Guide students in using multiple strategies flexibly and in combination. Be sure that they know which strategies that they are using, in addition to how, when, and why they are doing so.

• Be sure to work explicit explanations, modeling, monitoring, and graduate release of responsibility into your teaching plans.

• Engage students in discussions about strategy use.

• Consider posting a chart on the classroom wall that lists the names of strategies introduced and used. Students (and teacher) can refer to the chart during classroom discussions.

• Modify mandated textbook lessons so that the focus moves away from decontextualized stand-alone strategies and toward contextualized strategy instruction.

• Be patient. It takes time for teachers and students to get used to a new way of teaching.

• Be curious about your own strategic-reading habits and share your experiences with students.

We urge L2 teachers to make a concerted effort to adjust their teaching of reading so that the focus is less on assessing reading and teaching stand-alone strategies and more on training strategic readers. Such an adjustment can make possible, for our L2 students, the bright future that accompanies strategic reading.

NOTE

1 Readers interested in a comprehensive review should consult, at a minimum, Almasi and Fullerton (2012); Anderson (2005, 2008, 2014); Block and Pressley (2007); Duke, Pearson, Strachan, and Billman (2011); Hedgcock and Ferris (2009); Grabe (2009); Mokhtari and Shoerey (2008); Nation (2009); and Pressley (2002a, 2002b).

REFERENCES

Allen, S. (2003). An analytic comparison of three models of reading strategy instruction.IRAL, 41. 319-338.

Almasi, J. F. & Fullerton, S. K. (2012).Teachingstrategicprocessesinreading(2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Anderson, N. J. (2005). L2 strategy research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.),Handbookofresearchinsecondlanguageteachingandlearning(pp. 757-772). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Anderson, N. J. (2008).PracticalEnglishlanguageteaching:Reading. New York: McGraw Hill.

Anderson, N. J. (2009). ACTIVE reading: The research base for a pedagogical approach in the reading classroom. In Z.H. Han & N. J. Anderson (Eds.),Secondlanguagereadingresearchandinstruction:Crossingtheboundaries(pp. 117-143). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Anderson, N. J. (2014). Developing engaged second language readers. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.),TeachingEnglishasasecondorforeignlanguage(4th ed., pp. 170-188). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Baker, L. (2002). Metacognition in comprehension instruction. In C. Block & M. Pressley (Eds.),Comprehensioninstruction:Research-basedbestpractices(pp. 77-95). New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, I. L. & McKeown, M. G. (2001). Inviting students into the pursuit of meaning.EducationalPsychologyReview, 13, 225-241.

Beck, I. L. & McKeown, M. G. (2006).ImprovingcomprehensionwithQuestioningtheAuthor:Afreshandexpandedviewofapowerfulapproach. New York: Scholastic.

Block, C. C. & Pressley, M. (2007). Best practices in teaching comprehension. In L. B. Gambrell, L. Mandel Morrow, & M. Pressley (Eds.),Bestpracticesinliteracyinstruction(3rd ed., pp. 220-242). New York: Guilford Press.

Brown, R. (2008). The road not yet taken: A transactional strategies approach to comprehension instruction.TheReadingTeacher, 61, 538-547.

Davidson, J. L. & Wilkerson, B. C. (1988).Directedreading-thinkingactivities. Monroe: Trillium Press.

Dixon, C. N. & Nessel, D. D. (1992).Meaningmaking:Directedreadingandthinkingactivitiesforsecondlanguagestudents. Englewood Cliffs: Alemany Press.

Duke, N. K. & Pearson, P. D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.),Whatresearchhastosayaboutreadinginstruction(3rd ed., pp. 205-242). Newark: International Reading Association.

Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Strachan, S. L., & Billman, A. K. (2011). Essential elements of fostering and teaching reading comprehension. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.),Whatresearchhastosayaboutreadinginstruction(4th ed., pp. 51-93). Newark: International Reading Association.

El-Dinary, P. (2002). Challenges of implementing transactional strategies instruction for reading comprehension. In C. Block & M. Pressley (Eds.),Comprehensioninstruction:Research-basedbestpractices(pp. 201-215). New York: Guilford Press.

Freeman, Y. S. & Freeman, D. E. (2009).AcademiclanguageforEnglishlanguagelearnersandstrugglingreaders. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Grabe, W. (2009).Readinginasecondlanguage:Movingfromtheorytopractice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Grabe, W. (2010). Fluency in reading—thirty-five years on.ReadinginaForeignLanguage, 22, 71-83.

Grabe, W. & Stoller, F. L. (2011).Teachingandresearchingreading(2nd ed.). New York: Pearson Longman.

Grabe, W. & Stoller, F. L. (2014). Teaching reading for academic purposes. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.),TeachingEnglishasasecondorforeignlanguage(4th ed., pp. 189-205). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Guthrie, J. T., Klauda, S. L., & Ho, A. N. (2013). Modeling the relationships among reading instruction, motivation, engagement, and achievement for adolescents.ReadingResearchQuarterly, 48, 9-26.

Guthrie, J. T., McRae, A., Coddington, C. S., Klauda, S. L., Wigfield, A., & Barbosa, P. (2009). Impacts of comprehensive reading instruction on diverse outcomes of low- and high-achieving readers.JournalofLearningDisabilities, 42, 195-214.

Guthrie, J. T. & Taboata, A. (2004). Fostering the cognitive strategies of reading comprehension. In J. T. Guthrie, A. Wigfield, & K. C. Parencevich (Eds.),Motivatingreadingcomprehension:Concept-orientedreadinginstruction(pp. 87-112). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & Parencevich, K. C. (Eds.). (2004).Motivatingreadingcomprehension:Concept-orientedreadinginstruction. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hedgcock, J. S. & Ferris, D. R. (2009).TeachingreadersofEnglish:Students,texts,andcontexts. New York: Routledge.

Hudson, T. (2007).Teachingsecondlanguagereading. New York: Oxford University Press.

Janzen, J. (1996). Teaching strategic reading.TESOLJournal, 6, 6-9.

Janzen, J. (2001). Strategic reading on a sustained content theme. In J. Murphy & P. Byrd (Eds.),Understandingthecoursesweteach:LocalperspectivesonEnglishlanguageteaching(pp. 369-389). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Klingner, J. & Vaughn, S. (2000). The helping behaviors of fifth graders while using collaborative strategic reading during ESL content classes.TESOLQuarterly, 34, 69-98.

Klingner, J. & Vaughn, S. (2004). Strategies for struggling second-language readers. In T. Jetton & J. Dole (Eds.),Adolescentliteracyresearchandpractice(pp. 183-209). New York: Guildford Press.

Klinger, J., Vaughn, S., Boardman, A., & Swanson, E. (2012).Nowwegetit!Boastingcomprehensionwithcollaborativestrategicreading. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Koda, K. (2005).Insightsintosecondlanguagereading. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kuhn, M. & Schwanenflugel, P. (Eds.). (2008).Fluencyintheclassroom. New York: Guilford Press.

McEntire, J. & Williams, J. (2009).Makingconnectionsintermediate:Astrategicapproachtoacademicreading. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McKeown, M. G., Beck, I. L., & Blake, R. G. K. (2009). Rethinking reading comprehension instruction: A comparison of instruction for strategies and content approaches.ReadingResearchQuarterly, 44, 218-253.

Mokhtari, K. & Sheorey, R. (Eds.). (2008).Readingstrategiesoffirst-andsecond-languagelearners:Seehowtheyread. Norwood: Christopher-Gordon.

Nation, I. S. P. (2008).Teachingvocabulary:Strategiesandtechniques. Boston: Heinle Cengage.

Nation, I. S. P. (2009).TeachingESL/EFLreadingandwriting. New York: Routledge.

Oczkus, L. D. (2010).Reciprocalteachingatwork:Powerfulstrategiesandlessonsforimprovingreadingcomprehension(2nd ed.). Newark: International Reading Association.

Palincsar, A. & Brown, A. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities.CognitionandInstruction, 1, 117-175

Pressley, M. (2002a). Comprehension strategy instruction: A turn-of-the-century status report. In C. Block & M. Pressley (Eds.),Comprehensioninstruction:Research-basedbestpractices(pp. 11-27). New York: Guilford Press.

Pressley, M. (2002b). Metacognition & self-regulated comprehension. In A. Farstrup & S. Samuels (Eds.),Whatresearchhastosayaboutreadinginstruction(pp. 291-309). Newark: International Reading Association.

Pressley, M. (2006).Readinginstructionthatworks(3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Pressley, M. & Harris, S. (2006). Cognitive strategies instruction: From basic research to classroom instruction. In P. Alexander & P. Winne (Eds.),Handbookofeducationalpsychology(2nd ed., pp. 265-286). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Pritchard, R. (2004). Strategic reading for English learners: Principles and practices.TheCATESOLJournal, 16, 29-42.

Rasinski, T. V. (2010).Thefluentreader:Oralandsilentreadingstrategiesforbuildingfluency,wordrecognitionandcomprehension(2nd ed.). New York: Scholastic Books.

Schmitt, N. (2000).Vocabularyinlanguageteaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shiotsu, T. (2010).ComponentsofL2reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snow, M. A. (2014). Content-based and immersion models of second/foreign language teaching. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.),TeachingEnglishasasecondorforeignlanguage(4th ed., pp. 438-454). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Spörer, N., Brunstein, J. C., & Kieschke, U. (2009). Improving students’ reading comprehension skills: Effects of strategy instruction and reciprocal teaching.LearningandInstruction, 19, 272-286.

Stahl, K. A. D. (2008). The effects of three instructional methods on the reading comprehension and content acquisition of novice readers.JournalofLiteracyResearch, 40, 359-393.

Stoller, F. L. (2004). Content-based instruction: Perspectives on curriculum planning.AnnualReviewofAppliedLinguistics, 24, 216-283.

Swan, E. A. (2003).Concept-orientedreadinginstruction:Engagingclassrooms,lifelonglearners. New York: Guilford Press.

Takala, M. (2006). The effects of reciprocal teaching on reading comprehension in mainstream and special (SLI) education.ScandinavianJournalofEducationalResearch, 50, 559-576.

Wigfield, A., Guthrie, J. T., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Klauda, S. L., McRae, A., & Barbosa, P. (2008). Role of reading engagement in mediating effects of reading comprehension instruction on reading outcomes.PsychologyintheSchools, 45, 432-445.

Wilkinson, I. A. G. & Son, E. Y. (2011). A dialogic turn in research on learning and teaching to comprehend. In M. L. Kamil, P. D. Pearson, E. B. Moje, & P. P Afflerbach (Eds.),Handbookofreadingresearch:VolumeⅣ (pp. 359-387). New York: Routledge.

Zhang, L.J. (2008). Constructivist pedagogy in strategic reading instruction: Exploring pathways to learner development in the English as a second language (ESL) classroom.InstructionalScience, 36, 89-116.

Zimmerman, C. B. (2009).Wordknowledge:Avocabularyteacher’shandbook. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zimmerman, C. B. (2014). Teaching and learning vocabulary for second language learners. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.),TeachingEnglishasasecondorforeignlanguage(4th ed., pp. 288-302). Boston: Cengage Learning.

杂志排行

当代外语研究的其它文章

- Thinking Metacognitively about Metacognition in Second and Foreign Language Learning, Teaching, and Research:Toward a Dynamic Metacognitive Systems Perspective

- Metacognition Theory and Research in Second Language Listening and Reading: A Comparative Critical Review

- Codeswitching in East Asian University EFL Classrooms:Reflecting Teachers’ Voices①

- Modality, Vocabulary Size and Question Type asMediators of Listening Comprehension Skill

- Toward a Theoretical Framework for Researching Second Language Production

- Learning Mandarin in Later Life: Can Old Dogs Learn New Tricks?①