Chronic disease and the link to physical activity

2013-06-09LrryDurstineBenjminGordonZhengzhenWngXijunLuo

J.Lrry Durstine,Benjmin Gordon,Zhengzhen Wng,Xijun Luo,c

aDepartment of Exercise Science,The University of South Carolina,Columbia,SC 29208,USA

bCollege of Sport Science,Beijing Sport University,Beijing 100084,China

cSport Department,Guizhou University,Guiyang 550025,China

Review

Chronic disease and the link to physical activity

J.Larry Durstinea,*,Benjamin Gordona,Zhengzhen Wangb,Xijuan Luob,c

aDepartment of Exercise Science,The University of South Carolina,Columbia,SC 29208,USA

bCollege of Sport Science,Beijing Sport University,Beijing 100084,China

cSport Department,Guizhou University,Guiyang 550025,China

Chronic diseases have become a focal point of public health worldwide with estimates of trillions of dollars in annual health care cost and causing more than 36 million deaths a year.Lifestyle factors such as physical inactivity are heavily correlated with the development of many chronic diseases.New strategies for primary and secondary disease prevention are desperately needed to aid in blunting the negative economic and social impact of these diseases.Physical activity(PA)and exercise are now considered principal interventions for use in primary and secondary prevention of chronic diseases.Currently,more emphasis in primary prevention of disease is necessary to reduce disease risk in youth and adults;however with chronic disease prevalence so high,similar emphasis is also necessary for secondary prevention in those children and adults already inflicted with chronic diseases.Conditions such as cardiovascular disease,type 2 diabetes,obesity,and cancer are drastically improved when PA and exercise are part of a medical management plan.In addition,the national PA guidelines in conjunction with PA promotion tools like Exercise is Medicine™are needed to promote increased PA and exercise levels worldwide.

Copyright©2012,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.

Chronic disease;Physical activity;Primary prevention;Secondary prevention

1.Introduction

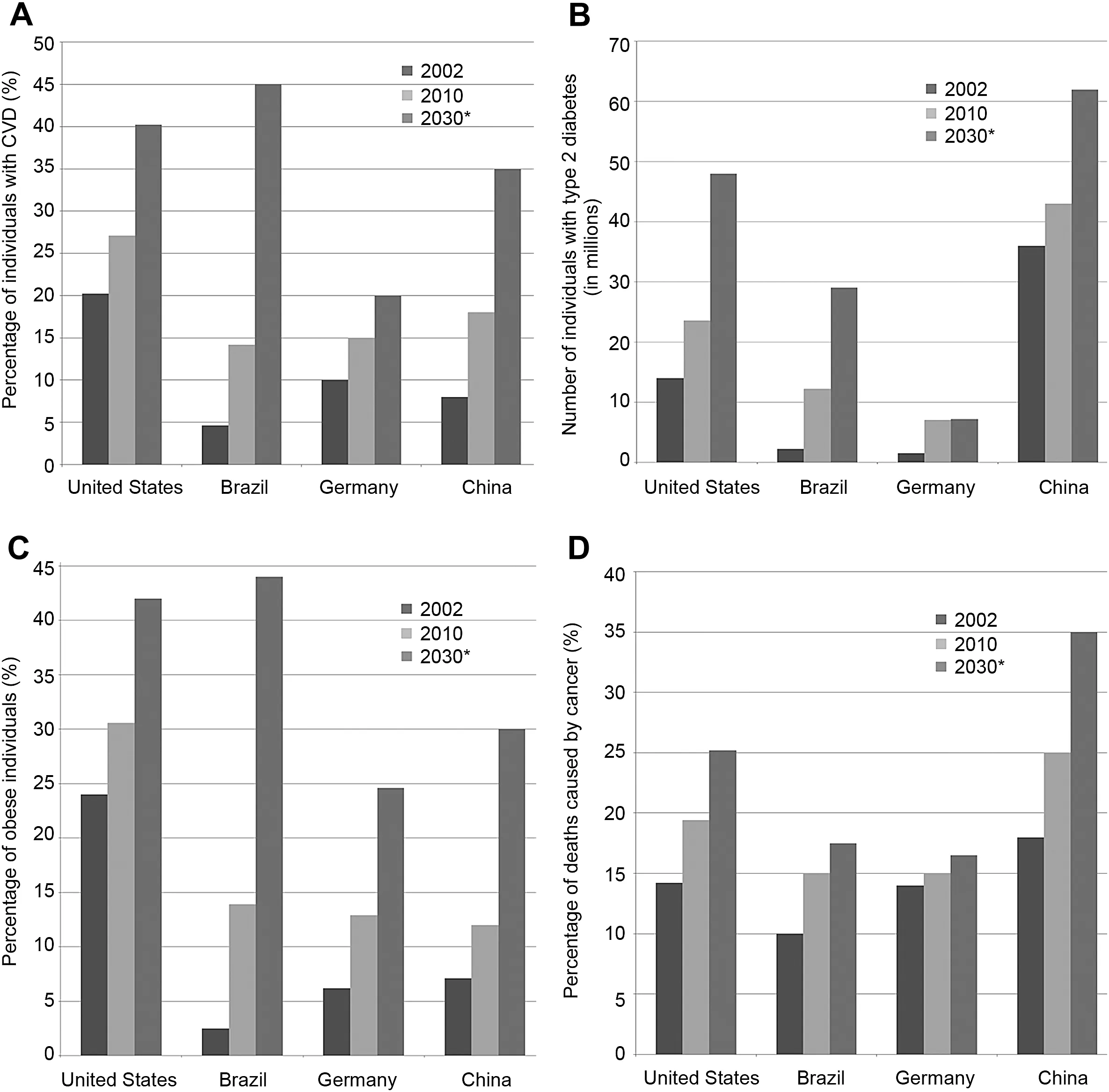

Currently,five babies are born per second in the world, and these children can anticipate living longer than previous generations with a life expectancy of more than 69 years1which is approximately 6 years longer than the life expectancy of a mere 20 years ago.1Even though children are expected to live longer,the quality of their lives is increasingly threatened by disease.Presently,chronic disease is the number one cause of death in the United States(U.S.)and the world.2In the past century a dramatic shift from non-industrialized countries suffering from communicable diseases to industrialized/modernized countries burdened with chronic diseases has taken place.This shift continues in many areas of the world including some of the most heavily populated countries such as China and Brazil(Fig.1).3—11The increase in chronic disease rates has created an enormous social, emotional,and economic burden that prevails throughout the world.

2.Physical activity(PA)and disease prevention

The most prevalent chronic diseases are cardiovascular disease(CVD),cancer,type 2 diabetes,various respiratory diseases,and osteoarthritis.12These diseases are burdensome, debilitating and potentially lethal to individuals inflicted,and while debilitating,medical treatment and annual health care costs continue to rise into trillions of dollars each year.13In the past,these diseases were associated with older populations,however because of lifestyle shifts,chronic diseases are now becoming more prominent in younger adults leaving them burdened and encumbered with health care concerns for the rest of their lives.14One lifestyle shift that has been identified as being in part responsible for the earlier onset of chronic disease is the prevalence of physical inactivity.15PA and exercise are considered a principal intervention for primary and secondary disease prevention.16Nonetheless,physical inactivity is escalating in all age groups around the world, especially adolescents.17—19A recent investigation conducted in the U.S.found that 77%of surveyed children under the age of 13 had not performed any vigorous PA in the past 7 days while only a meager 15%met the recommended 60 min of PA per day.20With this information in mind,incorporating PA and exercise in everyday living is essential for primary disease prevention.

Fig.1.(A)The percentage of individuals estimated having cardiovascular disease(CVD,not including high blood pressure),(B)the number of individuals with type 2 diabetes,(C)the percentage of individuals considered obesity,and(D)the percentage of individuals killed by cancer in United States,Brazil,Germany,and China by year including 2002,2010,and 2030.3—11*Values approximated from references.

Lifestyle factors such as physical inactivity are heavily correlated with the development of chronic disease.This relationship is supported by epidemiologic studies completed over the past century.21Even though physical inactivity is not the only lifestyle factor associated with the development of chronic disease,this factor in recent years has received much interest.Initial investigations examining the relationship between PA and chronic disease development were performed in 1953 by Morris et al.,22,23who examined CVD risk in London’s double-decker bus conductors and drivers.He found that the more active conductors were less likely to suffer from CVD than the inactive drivers.23This work was groundbreaking and was the first major analysis showing long-term health benefits associated with PA and exercise.As Morris was publishing this work,Paffenbarger et al.24were developing a similar investigation concerning California longshoremen. His research team investigated 6351 longshoremen ages 35—74 who were classified by job description which was based on PA level.Similar to the results of Morris,the more physically active longshoremen were found to have lower allcause mortality rates.Some 33 years after the initial Morris study,the relationship was again depicted when Paffenbarger et al.25released the Harvard alumni study.In this long term investigation,Paffenbarger et al.25followed 19,936 Harvard alumni,aged 35—74 for 16 years(1962—1978)and reported 1413 alumni whose primary cause of death was from chronic disease.However,all-cause mortality was better for individuals having higher PA levels.Three years later Blair et al.26released another landmark study linking PA to all-cause mortality.This study followed 13,344 patients receiving preventive medical examinations at the Cooper Clinic in Dallas,Texas from 1970 to 1981.Mortality rate for thesepatients was significantly correlated with the amount of PA completed.These pioneering studies showcase the importance of being physically active and the potential life-threatening effects of physical inactivity.

These monumental studies initiated an increased awareness for the need to become physically active for the purpose of developing and maintaining good health.In 1995,Pate et al.2summarized the importance of PA in a position statement with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine(ACSM).A primary objectiveoftheserecommendationswasto encourage increased PA participation among Americans of all ages.The issuing of these public health recommendations regarding the types and amount of PA and exercise needed for good health and disease prevention represent the first evidence-based guidelines for PA and exercise in the U.S.Some 4 years later in 1999,Australia released the first ever national PA guidelines.27These guidelines were followed in 2008 when the National PA Guidelines for the U.S.were released.28In the last decade other countries have drafted guidelines for PA including Canada,UK,Ireland,Austria,Finland,Brazil, Japan,Sweden,and China.

The importance of PA and exercise in regards to improving health has slowly been propagated throughout the world, however even with this increased awareness,the world levels of PA over the past decade have remained unchanged and in a few settings even decreased.29—31Some areas in the world have recorded sedentary behavior(any PA that has an energy requirement of less than 1.5 METs)levels greater than 50% with countries like Australia and the U.S.recording the worse levels.32Data reported from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(NHANES)cohort indicate that on the average U.S.children and adults spend more than 55%of their awaking hours as sedentary.33Similar results are reported for Australian adults who spend 57%of their day as sedentary. Even countries that are typically thought of as more physically active are now reported as having higher levels of sedentary behavior.34However,caution is needed when comparing values of sedentary behavior between studies.Early studies used self-reporting as the primary method for measuring PA, but over time PA studies using accelerometer methodology have gained prominence.This change in data collection methods(e.g.,accelerometervs.self-report)can likely create PA differences that do not reflect behavior change.To truly compare results from any type of activity study,the research designs considered must receive careful analysis to ensure that similardata collection methodsare used.Nonetheless, evidence is readily available to support that a lifetime of physical inactivity provides physiological disadvantages that ultimately leads to poor health and increases the likelihood for the early onset of chronic disease.35—37

As previously noted,chronic diseases are now the leading cause of death in the world and account for 63%of all deaths in the year 2010.38Both epidemiological and longitudinal intervention evidence fully support the use of PA and exercise in the primary prevention of chronic disease.Though many countries are presently advocating for increased exercise and PA,these actions unfortunately have yet resulted in dramatic change.A more concerted effort involving all levels of the ecological and social framework is needed to fully embrace PA change.

Nevertheless,as PA and exercise provide many primary prevention health benefits,PA and exercise also provide similar benefits in secondary disease prevention.When PA and exercise are initiated after a chronic disease is diagnosed, many of the harmful disease effects are ameliorated and in some cases(e.g.,type 2 diabetes)the disease progression is slowed or halted.39PA and exercise when used as part of the medical management plan for secondary disease prevention will almost always improve the quality of life and potentially extend the life of a disease individual.40In this regard,the benefits of PA and exercise depend on the type,severity,and comorbidities of the disease.7

3.Disease and loss of functional capacity

The detrimental physiological effects of physical inactivity and sedentary behavior on health and physical functioning are well established.41Individuals with a chronic disease are likely to become less physically active which in turn leads to a cycle of deconditioning.The result of this downward cycle is a loss of functional capacity and subsequent further reductions in the ability to perform PA and exercise.In order to stop this downward cycle and increase functional capacity,individuals with a chronic disease should receive information and/or counseling regarding the safety,effectiveness,and proper use of PA and exercise prescription.If this cycle of deconditioning is not stopped,the consequences for poor long term health and suboptimal quality of life are greatly increased.

In the last several decades much attention has been directed toward primary and secondary disease prevention by developing the role of PA and exercise to improve health and physical fitness.From a secondary perspective,the initial goals for increasing PA and exercise are to reverse the physical deconditioning resulting from physicalinactivity and/or sedentary behavior,optimize physicalfunctioning,and enhance overall health and well-being.40Weiler et al.42recently wrote that various professional bodies now recognize the existing large evidence base showing the potential for cost-effectiveness and the significance of promoting PA for primary prevention and secondary disease treatment.He reviewed 39 different national PA guidelines and found that each contained PA promotion features.He suggests that if a patient’s medical management plan for any disease where PA and exercise are known to be beneficial does not contain PA and exercise recommendations or does not provide advice regarding appropriately PA,a strong possibility exists that medical negligence has occurred.

Within any disease or medical condition,a wide range of physical abilities and varied ways for individuals to respond to PA and exercise exist.This diversity in physical abilities and PA responses are largely determined by one or more of the following:the severity and/or progression of the disease or medical condition,the response to treatments,and thepresence of other comorbidities.Consequently,the specific health outcomes for PA and exercise programming are not always known,but may range from arresting or attenuating the deterioration in functional capacity to markedly improving physical and health status.

4.PA,exercise,and disease prevention

For many diseases expected health benefits resulting from increased PA and exercise are not always known.Presently, a move toward active support from the medical community in recommending a medical management plan that includes PA and exercise programming and routine referral to exercise professionals is critical.Trained professionals can provide counseling that will facilitate change and optimize the use of intervention strategies to promote primary and secondary disease prevention.Such increased interest,support,and encouragement from the medical management team as well as developing a better understanding in how to design PA and exercise programs tailored to each individual’s needs are positive steps toward optimizing and obtaining goals for improved physical functioning,health,and well-being.The remainder of this review is dedicated toward describing the benefitsofestablishing PA and exercise assecondary prevention for specific chronic diseases including,CVD,type 2 diabetes,obesity,and cancer.Many diseases such as osteoarthritis are not reviewed.However,even though many health conditions such as osteoarthritis and others are prominent chronic diseases that are potentially debilitating and severely limiting,a discussion of these diseases is beyond the scope of this review.For more information on osteoarthritis or other diseases and secondary prevention,the reader is encouraged to review some references.43,44

4.1.Cardiovascular disease

CVD is the most common chronic disease around the world (Fig.1A).45Approximately one-half of chronic disease deaths in 2010 were credited to CVD.46The term cardiovascular disease includes coronary heart disease,cerebrovascular disease,peripheral arterial disease,rheumatic heart disease, congenital heart disease,deep vein thrombosis,and pulmonary embolism among others.With the exception of genetic cardiovascular disease,a high correlation exists among CVD and physical inactivity.47This correlation was established over the course of several decades by epidemiologic studies designed to determine factors associated with CVD risk.These factors are characteristics that when present increase the possibility of being afflicted with disease.48Numerous risk factors are identified for CVD and are divided into modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.48Modifiable risk factors include elevated blood pressure,elevated blood cholesterol, elevated blood glucose levels,cigarette smoking,and obesity. Once PA,dietary,and smoking cessation interventions are addressed,the clinical manifestations are reduced.49By knowing whether an individual has one or more of these factors,their CVD risk or risk stratification(low risk, moderate risk,or high risk)as outlined by the ACSM or the American Heart Association(AHA)is established.49Risk stratification enhances the practitioner’s ability to understand a patient’s disease state and gives insight into potential disease progression.Once risk stratification is completed,the appropriate lifestyle modification interventions are identified and incorporated into a tailored medical management plan to reduce the risk of future cardiac events.The practitioner meets with the patient,reviews the plan,and gives counsel regarding various parts of the plan including lifestyle intervention.50

Currently,the number of individuals around the world with CVD embodies the need for PA and exercise as a lifestyle intervention.45Daily PA and exercise reduce CVD risk as well as signs and symptoms while increasing functional capacity. The 1995 guidelines produced by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research(AHCPR)51report that cardiovascular mortality is reduced in myocardial infarction patients who participate in secondary disease prevention such as comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programming that includes PA andexercise.51ForallCVD,thequalityoflifeisincreasedwhen medical programming includes PA and exercise training.52Generally,individuals with CVD who become physically active realize multiple benefits53including an improved functional capacity,improved muscular strength(when strength training is part of the rehabilitation program),reduction in submaximal heart rate,reduced blood pressure,reduced rate pressure product,reduced inflammatory markers,relief of angina symptoms,possible decreases in body weight,and increases in high density lipoprotein cholesterol(HDL-C).54Myocardial infarction patients enrolled into a 3—6-month cardiac rehabilitation program typically experience an 11%—36%increase in aerobic or functional capacity.55,56This large range of values is due to variation in initial fitness level and the amount of PA and exercise completed.56Increases in functional capacity provide for improving the ease to perform daily activities.57The mechanism for this improvement is associated with the reduction in the amount of myocardial ischemia brought on by increased functional capacity.58

Individuals diagnosed with CVD or having suffered a myocardial event should also receive educational information and counseling about the disease process and lifestyle intervention strategies in order to reduce the likelihood for further incidents.58The 2008 U.S.PA Guidelines state that moderate PA is safe for almost everyone including those with chronic diseases.Although these guidelines do not provide a specific prescription for CVD individuals,they do point out that more health benefits are seen when the exercise volume or dose is increased from 150 min to 300 min a week.28Other existing position statements and guidelines support this stance2such as the Swedish PA in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease Guidelines.59These Swedish guidelines give specific prescriptions for different manifestations of CVD. Other position statements such as the AHA/American College of Cardiology(ACC)2006 guidelines for secondary prevention of CVD state that patients should achieve a minimum of 5 days a week of moderate intensity PA for 30 min a day.49These guidelines and position statements are essential inproviding information for medical management professionals on the use of PA and exercise for secondary prevention.When used correctly,PA and exercise prescriptions based off of these guidelines provide substantial health gains.60Haennel and Lemire61reported that CVD patients benefited with significant reductions in the incidence and had improved mortality rates when 30—60 min a day(most days of the week)of PA was completed.Leon et al.53found that exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs reduced total mortality by 20%, cardiac mortality by 26%,nonfatal myocardial infarctions by 21%,and the need for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty(PTCA)by 19%when compared to the usual care control group.These secondary prevention disease improvements seen with PA and exercise in individuals with CVD are astounding and show that in many cases the detrimental effects of a lifetime of physical inactivity are blunted by comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programming that includes increased PA and exercise.

4.2.Type 2 diabetes

The incidence of diabetes mellitus is on the rise throughout the world and is vying for the most common chronic disease.62This rise is mostly due to escalating cases of type 2 diabetes. Shaw et al.62in 2009 reported 24 million Americans had diabetes(Fig.1B),a sizeable fraction of the 285 million cases worldwide.In addition,60%of Americans not diabetic were found to be prediabetic;a condition in which blood glucose levels are well above normal.63Risk estimates for Americans born after the year 2000 show that these individuals have a 33%greater chance of becoming type 2 diabetic.64Usually the onset of type 2 diabetes is associated with a decrease in life expectancy and an increased risk for developing other chronic disease such as CVD,but this disease process is heavily influenced by positive lifestyle change such as increased PA and exercise,and in some cases lifestyle change improves early mortality and morbidity rates.30,65Nonetheless, increasing physical inactivity levels are related to the rising rates of type 2 diabetes.63Presently,only 39%of type 2 diabetics reported meeting the level of PA recommended by the 2008 PA Guidelines,while 58%of healthy adults(not having type 2 diabetes)reported meeting the recommended level of PA.64Because of the reported PA and exercise health benefits for type 2 diabetics,lifestyle interventions incorporating PA and exercise are important for both primary and secondary disease prevention.

Aprimaryaimofthemedicalmanagementplanfordiabetics is to maintain optimal blood glucose,lipid,and blood pressure levels.When these three factors are properly maintained, abnormal physiological function returns to normal,and most symptoms and in some cases the entire diabetic disease process are ameliorated or postponed.66Traditionally,aerobic exercise has been a cornerstone of secondary prevention for type 2 diabetics.OneweekofmoderatetovigorousaerobicPAorexercise can positively change overall body insulin sensitivity.64Increased insulin sensitivity is directly related to an increased expression of GLUT4 receptors which subsequently will increase glucose uptake.In addition to increased insulin sensitivity,skeletal muscle proteins and enzymes associated with glucose metabolism and insulin signaling and expression are increased.64RegularPAandexercisealsopromotefatoxidation andmusclelipidstoragethatresultsinanincreasedfatoxidative capacity.67Furthermore,increases in PA and exercise levels are a factor in weight reduction.68Weight loss is associated with increases in HDL-C and significantly improves blood lowdensity-lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels.60Lastly, PA and exercise have an important role in effecting comorbidities commonly seen with type 2 diabetes.63Regular PA in most casesreducessystolicbloodpressurebutnotinallcases69while diastolic blood pressure is rarely lowered.64

Type 2 diabetics are encouraged to participate in both structured and unstructured PA and exercise.Also,the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans28suggest that additional health benefits are gained by completing up to 5 h (300 min)of moderate to vigorous PA a week.Diabetics are a group of individuals that could receive these additional benefits from increased PA,70and most guidelines suggest the inclusion of structured exercise programming as part of their medical management plan.66Structured exercise is performed at least three times a week—preferably five or more times per week with no more than 2 days of rest between exercise sessions.64,66This recommendation is based on the knowledge of the temporary nature of exercise-induced insulin effects.71Health benefits and functional capacity improvements are best optimized with 5—7 days a week of regular PA and exercise.Though most diabetics gain health benefits from brisk walking at moderate exercise intensity levels,more beneficial effects are seen with higher exercise intensity levels.72A recent meta-analysis found exercise intensity as the biggest determinant for blood glucose reduction in contrast to many who believe that exercise volume as the better determinant.73Even so,diabetics when starting to exercise or become more physically active are often limited by a low aerobic capacity(e.g.,the average type 2 diabetic has an aerobic capacity of 22.4 mL/kg/min which is well below the average adult).70As a result,the duration of each exercise session can be as short as 10 min,but with multiple daily 10-min segments(30 daily total minutes is recommended).40When considering diabetes,regular PA and exercise provides the greatest impact when included as part of the medical management plan.If these programs were implemented as part of primary or secondary prevention programming,global spread of this disease would be slowed.74

4.3.Obesity

Although obesity is not traditionally viewed as a chronic disease,it is heavily associated with negative health implications and is often linked to several chronic diseases including CVD,certain cancers,osteoarthritis,and type 2 diabetes.75The link between obesity and chronic disease is associated with obese individuals having very low levels of cardiorespiratory fitness and who are extremely physically inactive.15Obesity rates are increasing throughout the world and in 2008 over 300million individuals were viewed as obese(Fig.1C).76In the U.S.approximately one third of the population is considered obese77giving this country the highest obesity rate in the world.78Even so,countries once unaffected by the obesity blight are now experiencing substantial higher obesity rates. China,a country long not associated with high obesity has recently seen a dramatic spike in obesity along with an associated increase in hypertension,cancer,and type 2 diabetes.79Even though the current rate of obesity in China(5%)is low relative to that found in the rest of the world(14%),the China obesity rate is increasing and is alarming.7These rates changes have doubled over the past 10 years and are most disturbing because China’s population makes up one-fifth of the world population.Such obesity rate increases for manycountries pose serious implications for global health care cost.

Obesity is defined as a body mass index(BMI)excess of 3080and typically is a result of an improper balance of energy consumed and energy expended.When excess energy is consumed,the surplus is stored in adipose tissue.In addition, low levels of PA create a positive excess of energy exacerbating the imbalance causing an increase in storage of body fat.6Surplus body fat can alter physiologic function to include decreased insulin sensitivity with rising fasting insulin levels81and increased cholesterol synthesis.82These negative health attributes are associated with increased levels of systemic inflammation,and a steady reduction in functional capacity.83Some scientists believe that reduced functional capacity derived from low levels of PA in obese individuals is responsible for most of the negative health implications. Regardless,these factors are all linked to severe health concerns and chronic disease risk.84

When the energy balance is tilted in the opposite direction, so that more calories are expended than consumed,obesity does not usually occur.Thus,lifestyles interventions incorporating PA and regular exercise are essential strategies for primary and secondary obesity prevention.Recent investigations provide interesting data strongly supporting the notion that physical inactivity increases the risk for obesity(odds ratio 3.9,95%confidence interval 1.4—10.9).85Nonetheless, small increases in daily PA and regular exercise by the youth of today can serve as an essential approach for primary disease prevention.Still,because obesity rates are high,daily PA and regular exercise remain an important component of secondary prevention programming.

Because daily PA does aid in weight loss and ameliorates the physiologic dysfunction seen with obesity,guidelines from the National Heart,Lung,and Blood Institute encourage the use of PA and exercise to obtain a 10%weight reduction in overweight and obese individuals.86This recommendation is supported by the substantial evidence demonstrating that a 3%—5%reduction in body weight can substantially improve health risks.87Regardless of weight loss,daily PA improves an obese individual’s functional capacity and their cardiorespiratory fitness while reducing their risk for chronic disease.13In 2009 a position stand released by the ACSM recommends that at least 250 min of moderate to vigorous PA be completed each week by individuals who want to lose body fat.87This recommendation is very similar to the 2008 U.S.PA Guidelines recommending 300 min each week to optimizing health benefits.28While small amount of daily PA and exercise do provide health benefits,the amount of PA and exercise must be great enough to cause a negative energy balance to see reductions in body weight.

4.4.Cancer

During the past six decades,cancer prevalence has steadily increased to become the second leading cause of death in the world.88Nearly 15%of all deaths are attributed to cancer88while almost 600,000 deaths are attributed to cancer in the U.S.alone.10In some countries including China,cancer has surpassed CVD in having the highestmortality rate (Fig.1A,D).89Recently,the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics estimated that approximately 25%of all Chinese deaths are cancer-related.90Nevertheless,the World Health Organization estimates that over 30%of cancer cases are preventable by incorporating a lifestyle that includes PA and regular exercise.88Presently,several types of cancer are associated with physical inactivity while epidemiological studies report increased PA is associated with decreased risk for breast cancer,colon cancer,and prostate cancer.91,92

Even as PA and exercise lifestyle interventions are recognized strategies for primary prevention,these same interventions improve survival rates and quality of life for individuals already suffering from disease.91Thus,PA and exercise have been evaluated as a strategy in the secondary prevention for breast,colon,and prostate cancer.Most studies find improved mortality rates and quality of life when PA and exercise are incorporated into the medical management plan.91,93Few properly designed studies are available evaluating the use of PA and exercise in secondary disease prevention for many forms of cancer.Thus,opportunities for future investigations exist in a variety of cancer areas.Regarding PA and breast cancer,Holmes et al.94followed 2987 females diagnosed with breast cancer between 1984 and 1998 recording their PA levels.Women reaching at least 3 MET-h/week of PA had significantly higher survival rates relative to women achieving lower PA levels.In a similar study Holick et al.95followed 4482 females diagnosed with breast cancer between 1988 and 2001 and recorded PA levels.Their data support the conclusion that women reaching a minimum of 2.8 MET-h/week of PA had significantly improved survival rates.95Similar results are found for colon cancer and prostate cancer.96—98Because of this information,PA and exercise must be incorporated as part of a comprehensive medical management plan.In those instances when these lifestyle interventions are included, survival rates and quality of life are greatly improved in individuals afflicted with several forms of cancer.91

5.Conclusion

The prevalence of chronic disease throughout the world has lead scientists and health professionals to consider various means of primary disease prevention and secondary diseasetreatment.Throughout the discussion presented in this manuscript,the importance of PA and exercise for primary and secondary disease prevention is reviewed.This notion is an essential concept found within the ACSM initiativeExercise is Medicine™which promotes daily PA and exercise as a part of everyday life.Because of the many associated health benefits, PA and exercise should be viewed as a medication.As is the case for many chronic diseases,the health benefits of PA and exercise surpass those of conventional medications.Beta blockers commonly used in the treatment of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases result in resting heart rate reductions that are comparable to reductions found with regular exercise participation.Because of these health benefits, PA and exercise are now included as part of the medical management plan for many chronic diseases.One of the most notable benefits of using PA and exercise is the absence of side-effects,as opposed to those found with classic medication use.Unlike traditional medications,PA and exercise change the underlying mechanisms for physiological functioning, whereas traditional medications mask the signs or symptoms or alter physiologic functioning in an unnatural fashion. Improvements in cardiovascular function seen with PA and exercise are excellent examples.Exercise causes increased myocardial oxygen supply,99decreased myocardial oxygen demand,99increased myocardium electrical stability,100and overall improved myocardial function.101This improved myocardial function is associated with decreases in other variables such as heart rate,systolic blood pressure and blood catecholamine levels at rest and all sub-maximal exercise levels.102All of these changes contribute to a better functioning cardiovascularsystem and improved functional capacity.Physiological change brought on by PA and exercise is not limited to the cardiovascular system.In fact,all bodily systems are functionally altered and improved by PA and exercise.The realization of the importance of daily PA and regular exercise as a strategy in primary disease prevention has led many countries to develop national PA guidelines.In 1999, the Australian government in a move to improve overall health and reverse physical inactivity trends was the first government to develop national PA guidelines.The U.S.followed in 2008 whentheDepartmentofHealthandHumanServices announced and released the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.Following the U.S.lead,other countries including Canada,UK,Ireland,Austria,Finland,Sweden,and China each created their own national PA guidelines.The American guidelines reflect the dose—response relationship concept between volume of PA and exercise completed and health benefits achieved,and advise that health benefits are gained with 150 min/week,but that more health benefits are seen when 300 min of moderate PA is achieved.28

Chronic diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide. Their incident rates continue to increase and this increase is heavily associated with an increase in physical inactivity.35While obvious that more emphasis in primary prevention is necessary to reduce disease risk in youth and adults,similar emphasis is also necessary for secondary disease treatment in those children and adults already inflicted with chronic diseases.PA and exercise continue to gain recognition as important lifestyle interventions for use in primary prevention and secondary prevention.Many countries have developed PA guidelines,and these guidelines in conjunction with PA promotion tools such asExercise is Medicine™are needed to educate health professionals on the importance of exercise in disease management.As more countries incorporate PA and exercise as part of primary and secondary prevention strategies,chronic diseases such as CVD,type 2 diabetes,stroke, cancer,and many others,along with their health care costs will be reduced while the quality of life is improved.

1.World Health Organization.Life expectancy for the world population. Report of WHO expert consultation.Available at:http://www.who.int/ gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends/en/index. html;2008[accessed 12.05.12].

2.Pate RR,Pratt M,Blair SN,Haskell WL,Macera CA,Bouchard C,et al. Physical activity and public health.A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine.JAMA1995;273:402—7.

3.Moran A,Gu D,Zhao D,Coxson P,Wang C,Chen C,et al.Future cardiovascular disease in China.Circ Outcomes2010;3:243—52.

4.Mathers C,Loncar D.Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030.PLoS Med2006;3:e442.

5.Wild S,Roglic G,Green A,Sicree R,King H.Global prevalence of diabetes:estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030.Diabetes Care2004;27:1047—53.

6.Whiting D,Guariguata L,Weil C,Shaw J.IDF diabetes atlas:global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030.Diabetes Res Clin Pract2011;94:311—21.

7.Kelly T,Wang W,Chen C-S,Reynolds K,He J.Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030.Int J Obes2008;32:1431—7.

8.Finkelstein EA,Khavjou OA,Thompson H,Trogdon JG,Pan L, Sherry B,et al.Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030.Am J Prev Med2012;42:563—70.

9.Bray F,Jemal A,Grey N,Ferlay J,Forman D.Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index(2008—2030):a populationbased study.Lancet Oncol2012;13:790—801.

10.Mariotto AB,Yabroff KR,Shao Y,Feuer EJ,Brown ML.Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States:2010—2020.J Natl Cancer Inst2011;103:117—28.

11.Katalinic D,Plestina S.Cancer epidemic in Europe and Croatia:current and future perspectives.J Public Health2012;18:575—82.

12.World Health Organization.Chronic diseases.Report of WHO expert consultation.Available at:http://www.who.int/topics/chronic_diseases/ en/[accessed 12.05.12].

13.The World Economic Forum.The Global Economic Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases.Available at:http://www.weforum.org/reports/ global-economic-burden-non-communicable-diseases[accessed 12.05.12].

14.Flynn MA,McNeil DA,Maloff B,Mutasingwa D,Wu M,Ford C,et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with“best practice”recommendations.Obes Rev2006;7(Suppl.1):7—66.

15.Blair SN,Brodney S.Effects of physical inactivity and obesity on morbidity and mortality:current evidence and research issues.Med Sci Sports Exerc1999;31:S646—62.

16.Warburton DE,Nicol CW,Bredin SS.Health benefits of physical activity:the evidence.CMAJ2006;174:801—9.

17.Katzmarzyk PT,Janssen I.The economic costs associated with physical inactivity and obesity in Canada:an update.Can J Appl Physiol2004;29:90—115.

18.Raitakari OT,Porkka KV,Taimela S,Telama R,Rasanen L,Viikari JS. Effects of persistent physical activity and inactivity on coronary riskfactors in children and young adults.The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study.Am J Epidemiol1994;140:195—205.

19.Tremblay MS,Willms JD.Is the Canadian childhood obesity epidemic related to physical inactivity?Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord2003;27:1100—5.

20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Physical inactivity estimates,bycounty. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Features/ dsPhysicalInactivity/;2010[accessed 12.05.12].

21.Artinian NT,Fletcher GF,Mozaffarian D,Kris-Etherton P,Van Horn L, Lichtenstein AH,et al.Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults:a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.Circulation2010;122:406—41.

22.Morris JN,Crawford MD.Coronary heart disease and physical activity ofwork:evidence ofa nationalnecropsy survey.BrMedJ1958;2:1485—96.

23.Morris JN,Heady JA,Raffle PA,Roberts CG,Parks JW.Coronary heartdisease and physical activity of work.Lancet1953;265:1111—20.

24.Paffenbarger RS,Gima AS,Laughlin E,Black RA.Characteristics of longshoremen related fatal coronary heart disease and stroke.Am J Public Health1971;61:1362—70.

25.Paffenbarger Jr RS,Hyde RT,Wing AL,Hsieh CC.Physical activity,allcause mortality,and longevity of college alumni.N Engl J Med1986;314:605—13.

26.Blair SN,Kohl 3rd HW,Paffenbarger Jr RS,Clark DG,Cooper KH, Gibbons LW.Physical fitness and all-cause mortality.A prospective study of healthy men and women.JAMA1989;262:2395—401.

27.Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care(DHAC).National physical activity guidelines for Australians.Canberra,Australia:DHAC; 1999.

28.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services.2008Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.ODPHP Publication No.U0036.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.Also Available at:http:// www.health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf;2008[accessed12.05.12].

29.Bauman AE.Updating the evidence that physical activity is good for health:an epidemiological review 2000—2003.J Sci Med Sport2004;7:6—19.

30.Laaksonen DE,Lakka HM,Salonen JT,Niskanen LK,Rauramaa R, Lakka TA.Low levels of leisure-time physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness predict development of the metabolic syndrome.Diabetes Care2002;25:1612—8.

31.Troiano RP,Berrigan D,Dodd KW,Masse LC,Tilert T,McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer.Med Sci Sports Exerc2008;40:181—8.

32.World Health Organization.Physical inactivity:a global public health problem.Report of WHO expert consultation.Available at:http://www. who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_inactivity/en/; 2008 [accessed 12.05.12].

33.Crespo CJ,Keteyian SJ,Heath GW,Sempos CT.Leisure-time physical activity among US adults.Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.Arch Intern Med1996;156:93—8.

34.Wu YF,Ma GS,Hu YH,Li YP,Li X,Cui ZH,et al.The current prevalence status of body overweight and obesity in China:data from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey.Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi2005;39:316—20.

35.Booth FW,Laye MJ,Lees SJ,Rector RS,Thyfault JP.Reduced physical activity and risk of chronic disease:the biology behind the consequences.Eur J Appl Physiol2008;102:381—90.

36.Paffenbarger Jr RS,Hyde RT,Wing AL,Lee IM,Jung DL,Kampert JB. The association of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men.NEnglJMed1993;328:538—45.

37.Popkin BM,Kim S,Rusev ER,Du S,Zizza C.Measuring the full economic costs of diet,physical activity and obesity-related chronic diseases.Obes Rev2006;7:271—93.

38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Chronic disease prevention and health promotion.Available at:http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/ stats/index.htm;2012[accessed 12.05.12].

39.Sigal RJ,Kenny GP,Wasserman DH,Castaneda-Sceppa C,White RD. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes:a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association.DiabetesCare2006;29:1433—8.

40.Durstine JL,Painter P,Franklin BA,Morgan D,Pitetti KH,Roberts SO. Physical activity for the chronically ill and disabled.Sports Med2000;30:207—19.

41.Saltin B,Blomqvist G,Mitchell JH,Johnson Jr RL,Wildenthal K, Chapman CB.Response to exercise after bed rest and after training.Circulation1968;38(Suppl.5):11—7.

42.Weiler R,Feldschreiber P,Stamatakis E.Medicolegal neglect?The case for physical activity promotion and exercise medicine.Br J Sports Med2012;46:228—32.

43.Penninx BW,Messier SP,Rejeski WJ,Williamson JD,DiBari M, Cavazzini C,et al.Physical exercise and the prevention of disability in activities of daily living in older persons with osteoarthritis.Arch Intern Med2001;161:2309—16.

44.Bijlsma JW,Knahr K.Strategies for the prevention and management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol2007;21:59—76.

45.Lloyd-JonesD,AdamsRJ,BrownTM,CarnethonM,DaiS,DeSimoneG, et al.Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update:a report from the American Heart Association.Circulation2010;121:e46—215.

46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Heart disease.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/;2012[accessed 12.05.12].

47.Nocon M,Hiemann T,Muller-Riemenschneider F,Thalau F,Roll S, Willich SN.Association of physical activity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality:a systematic review and meta-analysis.Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil2008;15:239—46.

48.Helfand M,Buckley DI,Freeman M,Fu R,Rogers K,Fleming C,et al. Emerging risk factors for coronary heart disease:a summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S.Preventive Services Task Force.Ann Intern Med2009;151:496—507.

49.American College of Sports Medicine.ACSM’s resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription.6th ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams&Wilkins;2010.p.559—74.

50.McGuire KA,Janssen I,Ross R.Ability of physical activity to predict cardiovascular disease beyond commonly evaluated cardiometabolic risk factors.Am J Cardiol2009;104:1522—6.

51.Balady GJ,Ades PA,Comoss P,Limacher M,Pina IL,Southard D,et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs.Circulation2000;102:1069—73.

52.Schairer JR,Keteyian SJ,Ehrman JK,Brawner CA,Berkebile ND. Leisure time physical activity of patients in maintenance cardiac rehabilitation.J Cardiopulm Rehabil2003;23:260—5.

53.Leon AS,Franklin BA,Costa F,Balady GJ,Berra KA,Stewart KJ,et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease:an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology(Subcommittee on Exercise,Cardiac Rehabilitation,and Prevention)and the Council on Nutrition,Physical Activity,and Metabolism(Subcommittee on Physical Activity),in collaboration with the American association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation.Circulation2005;111:369—76.

54.O’Connor GT,Buring JE,Yusuf S,Goldhaber SZ,Olmstead EM, Paffenbarger Jr RS,et al.An overview of randomized trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction.Circulation1989;80:234—44.

55.Ades PA.Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease.N Engl J Med2001;345:892—902.

56.WengerNK,FroelicherES,Smith LK,AdesPA,BerraK, Blumenthal JA,et al.Cardiac rehabilitation as secondary prevention. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research and National Heart,Lung, and Blood Institute.Clin Pract Guide Quick Ref Guide Clin1995:1—23.

57.Ades PA,Savage PD,Brawner CA,Lyon CE,Ehrman JK,Bunn JY,et al. Aerobic capacity in patients entering cardiac rehabilitation.Circulation2006;113:2706—12.

58.Hamm LF,Sanderson BK,Ades PA,Berra K,Kaminsky LA,Roitman JL, et al.Core competencies for cardiac rehabilitation/secondary preventionprofessionals:2010 update:position statement of the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation.J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev2011;31:2—10.

59.Swedish National Institute of Public Health.Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of disease.Available at:http://www.fhi.se/en/ Publications/All-publications-in-english/Physical-Activity-in-the-Prevention-and-Treatment-of-Desease/;2012[accessed 12.05.12].

60.Smith Jr SC,Allen J,Blair SN,Bonow RO,Brass LM,Fonarow GC,et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease:2006 update:endorsed by the NationalHeart,Lung,andBloodInstitute.Circulation2006;113:2363—72.

61.Haennel RG,Lemire F.Physical activity to prevent cardiovascular disease.How much is enough?Can Fam Physician2002;48:65—71.

62.Shaw JE,Sicree RA,Zimmet PZ.Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030.Diabetes Res Clin Pract2010;87:4—14.

63.Sigal RJ,Kenny GP,Wasserman DH,Castaneda-Sceppa C.Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes.Diabetes Care2004;27:2518—39.

64.Colberg SR,Sigal RJ,Fernhall B,Regensteiner JG,Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR,et al.Exercise and type 2 diabetes:the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association:joint position statement executive summary.Diabetes Care2010;33:2692—6.

65.Laaksonen DE,Lindstrom J,Lakka TA,Eriksson JG,Niskanen L, Wikstrom K,et al.Physical activity in the prevention of type 2 diabetes: the Finnish diabetes prevention study.Diabetes2005;54:158—65.

66.Albright A,Franz M,Hornsby G,Kriska A,Marrero D,Ullrich I,et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand.Exercise and type 2 diabetes.Med Sci Sports Exerc2000;32:1345—60.

67.Cauza E,Hanusch-Enserer U,Strasser B,Ludvik B,Metz-Schimmerl S, Pacini G,et al.The relative benefits of endurance and strength training on the metabolic factors and muscle function of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus.Arch Phys Med Rehabil2005;86:1527—33.

68.Wing RR,Hill JO.Successful weight loss maintenance.Annu Rev Nutr2001;21:323—41.

69.Huot M,Arsenault BJ,Gaudreault V,Poirier P,Perusse L,Tremblay A, et al.Insulin resistance,low cardiorespiratory fitness,and increased exercise blood pressure:contribution of abdominal obesity.Hypertension2011;58:1036—42.

70.Boule NG,Kenny GP,Haddad E,Wells GA,Sigal RJ.Meta-analysis of the effect of structured exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness in type 2 diabetes mellitus.Diabetologia2003;46:1071—81.

71.Yates T,Davies M,Gorely T,Bull F,Khunti K.Rationale,design and baseline data from the Pre-diabetes Risk Education and Physical Activity Recommendation and Encouragement(PREPARE)programme study: a randomized controlled trial.Patient Educ Couns2008;73:264—71.

72.Braun B,Zimmermann MB,Kretchmer N.Effects of exercise intensity on insulin sensitivity in women with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.J Appl Physiol1995;78:300—6.

73.Boule NG,Haddad E,Kenny GP,Wells GA,Sigal RJ.Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus:a metaanalysis of controlled clinical trials.JAMA2001;286:1218—27.

74.Gillison FB,Skevington SM,Sato A,Standage M,Evangelidou S.The effects of exercise interventions on quality of life in clinical and healthy populations:a meta-analysis.Soc Sci Med2009;68:1700—10.

75.Van Cleave J,Gortmaker SL,Perrin JM.Dynamics of obesity and chronic health conditions among children and youth.JAMA2010;303:623—30.

76.Finkelstein EA,Trogdon JG,Cohen JW,Dietz W.Annual medical spending attributable to obesity:payer-and service-specific estimates.Health Aff(Millwood)2009;28:w822—31.

77.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.CDC vital signs:adult obesity.Available at:http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/AdultObesity/;2012 [accessed 12.05.12].

78.World Health Organization.Media centre:obesity and overweight. Available at:http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/;2010 [accessed 12.05.12].

79.He Y,Zhai F,Ma G,Feskens EJ,Zhang J,Fu P,et al.Abdominal obesity and the prevalence of diabetes and intermediate hyperglycaemia in Chinese adults.Public Health Nutr2009;12:1078—84.

80.Shields M,Carroll MD,Ogden CL.Adult obesity prevalence in Canada and the United States.NCHS Data Brief2011;56:1—8.

81.Venables MC,Jeukendrup AE.Physical inactivity and obesity:links with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus.Diabetes Metab Res Rev2009;25(Suppl.1):S18—23.

82.Gylling H,Hallikainen M,Pihlajamaki J,Simonen P,Kuusisto J, Laakso M,et al.Insulin sensitivity regulates cholesterol metabolism to a greater extent than obesity:lessons from the METSIM study.J Lipid Res2010;51:2422—7.

83.Gregor MF,Hotamisligil GS.Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity.Annu Rev Immunol2011;29:415—45.

84.de Souza SA,Faintuch J,Sant’anna AF.Effect of weight loss on aerobic capacity in patients with severe obesity before and after bariatric surgery.Obes Surg2010;20:871—5.

85.Pietilainen KH,Kaprio J,Borg P,Plasqui G,Yki-Jarvinen H,Kujala UM, et al.Physical inactivity and obesity:a vicious circle.Obesity(Silver Spring)2008;16:409—14.

86.Grundy SM,Cleeman JI,Daniels SR,Donato KA,Eckel RH, Franklin BA,et al.Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome:an American Heart Association/National Heart,Lung,and Blood Institute scientific statement.Curr Opin Cardiol2006;21:1—6.

87.Donnelly JE,Blair SN,Jakicic JM,Manore MM,Rankin JW,Smith BK. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand.Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults.Med Sci Sports Exerc2009;41:459—71.

88.World Health Organization.Media centre:cancer fact sheet.Available at:http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/;2012[accessed 12.05.12].

89.Wang JB,Jiang Y,Wei WQ,Yang GH,Qiao YL,Boffetta P.Estimation of cancer incidence and mortality attributable to smoking in China.Cancer Causes Control2010;21:959—65.

90.Chinese National Bureau of Statistics.Mortality Statistics.Available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2010/indexeh.htm[accessed 12.05.12].

91.Friedenreich CM,Orenstein MR.Physical activity and cancer prevention: etiologic evidence and biological mechanisms.JNutr2002;132:3456—64.

92.Trojian TH,Mody K,Chain P.Exercise and colon cancer:primary and secondary prevention.Curr Sports Med Rep2007;6:120—4.

93.Schmitz KH.Exercise for secondary prevention of breast cancer:moving from evidence to changing clinical practice.Cancer Prev Res(Phil)2011;4:476—80.

94.Holmes MD,Chen WY,Feskanich D,Kroenke CH,Colditz GA.Physicalactivity and survivalafterbreastcancerdiagnosis.JAMA2005;293:2479—86.

95.Holick CN,Newcomb PA,Trentham-Dietz A,Titus-Ernstoff L, Bersch AJ,Stampfer MJ,et al.Physical activity and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer.Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev2008;17:379—86.

96.Courneya KS,Friedenreich CM.Physical activity and cancer:an introduction.Recent Results Cancer Res2011;186:1—10.

97.de VriesE,Soerjomataram I,LemmensVE,Coebergh JW, Barendregt JJ,Oenema A,et al.Lifestyle changes and reduction of colon cancer incidence in Europe:a scenario study of physical activity promotion and weight reduction.Eur J Cancer2010;46:2605—16.

98.Halle M,Schoenberg MH.Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of colorectal carcinoma.Dtsch Arztebl Int2009;106:722—7.

99.Barnard RJ,Duncan HW,Baldwin KM,Grimditch G,Buckberg GD. Effects of intensive exercise training on myocardial performance and coronary blood flow.J Appl Physiol1980;49:444—9.

100.Billman GE.Aerobic exercise conditioning:a nonpharmacological antiarrhythmic intervention.J Appl Physiol2002;92:446—54.

101.Levy WC,Cerqueira MD,Harp GD,Johannessen KA,Abrass IB, Schwartz RS,et al.Effect of endurance exercise training on heart rate variability at rest in healthy young and older men.Am J Cardiol1998;82:1236—41.

102.Winder WW,Hagberg JM,Hickson RC,Ehsani AA,McLane JA.Time course of sympathoadrenal adaptation to endurance exercise training in man.J Appl Physiol1978;45:370—4.

Received 17 June 2012;revised 20 July 2012;accepted 22 July 2012

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:ldurstin@mailbox.sc.edu(J.L.Durstine)

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport

2095-2546/$-see front matter Copyright©2012,Shanghai University of Sport.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2012.07.009

杂志排行

Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Physical activity,sedentary behaviors,physical fitness,and their relation to health outcomes in youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: A review of the epidemiologic literature

- Physical activity and exercise training in young people with cystic fibrosis: Current recommendations and evidence

- Children and adolescents with Down syndrome,physical fitness and physical activity

- Reliability:What type,please!