Hepatic portal venous gas in pancreatic solitary metastasis from an esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

2013-05-22

Sapporo, Japan

Hepatic portal venous gas in pancreatic solitary metastasis from an esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

Takeshi Sawada, Yasushi Adachi, Manabu Noda, Kimishige Akino, Takefumi Kikuchi, Hiroaki Mita, Yoshifumi Ishii and Takao Endo

Sapporo, Japan

BACKGROUND:Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is a rare entity commonly associated with intestinal necrosis and fatal outcome, and various underlying diseases have been reported. Pancreatic solitary metastasis without local extension is also rare in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

METHODS:This report describes an interesting and unusual case of HPVG arising from pancreatic tumor. Autopsy revealed pathogenesis of HPVG and synchronous tumors of the esophagus and pancreas.

RESULTS:A 73-year-old man developed synchronous double tumor in the esophagus and pancreas several months before acute abdomen and his death, which were generated by HPVG. Autopsy revealed that HPVG was caused by gastric wall infarction owing to expansion of an isolated pancreatic metastasis from esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

CONCLUSIONS:This is the fi rst case of HPVG that was derived from pancreatic tumor inf i ltration. If he had been diagnosed with solitary pancreatic metastasis from esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the fi rst time, he might have an option for chemotherapy, which could let him live longer.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013;12:103-105)

hepatic portal venous gas; solitary pancreatic tumor; metastasis;

Introduction

Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is a rare condition frequently associated with bowel necrosis, and various underlying diseases, benign or lethal, have been recently reported.[1]However, pancreatic diseases are seldom reported as a cause of HPVG.[2]

It is sometimes diff i cult to distinguish solitary metastasized tumor from primary pancreatic carcinoma. Although solitary pancreatic metastasis is often originated from renal cell carcinoma, several other primary sites have been reported.[3]Distant metastasis to the pancreas without local extension is also infrequent, especially in esophageal carcinoma. We report here an extremely rare case of HPVG which is associated with solitary pancreatic metastasis from esophageal cancer.

Case report

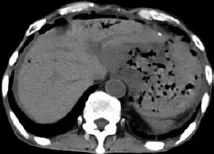

A 73-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for a two-month history of anorexia, dysphagia, and back pain. Endoscopy revealed an ulcerated tumor in the lower esophagus (Fig. 1A), diagnosed by biopsy as poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Computed tomography (CT) showed a large mass in the pancreas (Fig. 1B). Although an endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy or diagnostic laparotomy of the pancreatic mass was recommended, the patient demanded immediate discharge and supportive care. Three months later, he suddenly suffered from severe abdominal pain, fell into shock, and was re-admitted into the emergency department of the hospital. CT revealed the air in the pancreatic mass and liver, indicative of HPVG (Fig. 2). He died in the next day.

Postmortem examination revealed an esophageal tumor, distinct from a pancreatic tumor, withoutthoracic/abdominal lymph node swelling. The pancreatic tumor adhered to the gastric posterior wall. Neither intestinal necrosis nor intra-abdominal abscess was observed. Microscopic examination revealed that carcinoma cells had invaded the muscularis propria of the esophagus, with lymphatic vessel involvement. The pancreatic tumor consisted of poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma similar to the esophageal carcinoma (Fig. 3A, B), indicating a solitary pancreatic metastasis from the esophagus. This was conf i rmed by immunostaining (Fig. 3C-E). Additionally, there was massive inf i ltration of cancer cells into the gastric serosa, and hemorrhagic infarction of the gastric wall caused by arterial obliteration with the tumor, resulting in gastric perforation, gastropancreatic fi stula, and bacterial peritonitis in turn.

Fig. 1.Endoscopic and CT findings on the first admission.A: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing an elevated tumor with an ulcer in the lower thoracic esophagus (maximum diameter 25 mm). The tumor is easy to bleed by the contact.B: A large heterogeneously enhanced mass (maximum diameter 88 mm) in the pancreatic body shown by contrast-enhanced abdominal CT. Primary pancreatic tumor, including atypical types, is suspected.

Fig. 2.Plain abdominal CT showing ascites, free intraperitoneal air around the liver and air in the liver, pancreatic mass, and gastric wall. HPVG is diagnosed.

Discussion

It is generally accepted that intestinal ischemia and/or necrosis is the most common cause for HPVG, with concomitantly poorer prognosis. Other non-ischemic underlying conditions such as intestinal dilatation, intraperitoneal abscess, inf l ammatory bowel disease and intraperitoneal tumor have been described,[1,4]in addition to various gastric pathogeneses of HPVG like peptic ulcer, malignancy, and gastroscopic biopsy.[5]HPVG is associated with pancreatic diseases, radiochemotherapy for esophageal cancer, and endoscopic procedures.[2,6-8]In this report we fi rst report that gastric infarction owing to tumor inf i ltration into the gastric serosa can cause HPVG. Although the precise mechanism for HPVG is uncertain, the pathogenic factors for HPVG might include mucosal damage, sepsis, and intestinal distention.[4]The former two factors would be decisive in this case.

Though metastatic pancreatic tumors are infrequent, but can be seen in the colon, lung, breast, and kidney.[3,9]Pancreatic solitary metastasis is extremely uncommon and accounts for less than 2% of all pancreatic malignancies.[9]Moreover, distant metastases of esophageal cancer are commonly seen in the distant lymph node, liver, and lung, but extremely rare in the pancreas.[10,11]Most patients with metastatic pancreatic tumor are not candidates for surgical resection since they have widespread systemic disease at the time of diagnosis. However, the eff i cacy of surgical excision of isolated pancreatic metastases has been reported with a long-term survival rate.[3,12]In the present case, systemicchemotherapy might have been an option, which may provide a surgical treatment.

Fig. 3.Histological examination (HE staining) showing that both esophageal tumor (A) and pancreatic tumor (B) are poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Immunohistochemical study showing both expressed p63 (C) and high-molecular weight keratin (D) but not low-molecular weight keratin (E), p16, p53, CEA, or CA19-9.

Contributors:AY proposed the study. ST wrote the fi rst draft. All authors contributed to clinical works and analysis. ET is the guarantor.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benef i ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Kinoshita H, Shinozaki M, Tanimura H, Umemoto Y, Sakaguchi S, Takifuji K, et al. Clinical features and management of hepatic portal venous gas: four case reports and cumulative review of the literature. Arch Surg 2001;136: 1410-1414.

2 Wu JM, Wang MY. Hepatic portal venous gas in necrotizing pancreatitis. Dig Surg 2009;26:119-120.

3 Robbins EG 2nd, Franceschi D, Barkin JS. Solitary metastatic tumors to the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:2414-2417.

4 Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, Benf i eld JR, Hechtman HB. Hepatic--portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical signif i cance. Ann Surg 1978;187:281-287.

5 Wiesner W, Mortelé KJ, Glickman JN, Ji H, Ros PR. Portalvenous gas unrelated to mesenteric ischemia. Eur Radiol 2002;12:1432-1437.

6 Herman JB, Levine MS, Long WB. Portal venous gas as a complication of ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:828-829.

7 Duchon R, Pindak D, Sucha R, Bernadic M, Dolnik J, Pechan J. Portomesenteric vein gas and pneumatosis intestinalis--a rare complication after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy in oesophageal cancer. Bratisl Lek Listy 2011;112:463-465.

8 Ahmed K, Atiq M, Richer E, Neff G, Kemmer N, Safdar K. Careful observation of hepatic portal venous gas following esophageal variceal band ligation. Endoscopy 2008;40:E103.

9 Roland CF, van Heerden JA. Nonpancreatic primary tumors with metastasis to the pancreas. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1989; 168:345-347.

10 Quint LE, Hepburn LM, Francis IR, Whyte RI, Orringer MB. Incidence and distribution of distant metastases from newly diagnosed esophageal carcinoma. Cancer 1995;76:1120-1125.

11 Chan KW, Chan EY, Chan CW. Carcinoma of the esophagus. An autopsy study of 231 cases. Pathology 1986;18:400-405.

12 Reddy S, Wolfgang CL. The role of surgery in the management of isolated metastases to the pancreas. Lancet Oncol 2009;10: 287-293.

Received January 27, 2012

Accepted after revision May 2, 2012

AuthorAff i liations:Division of Gastroenterology (Sawada T, Adachi Y, Noda M, Akino K, Kikuchi T, Mita H and Endo T) and Department of Pathology (Ishii Y), Sapporo Shirakaba-dai Hospital, Sapporo, Japan

Yasushi Adachi, MD, PhD, Division of Gastroenterology, Sapporo Shirakaba-dai Hospital, 2-18 Tsukisamu-Higashi, Toyohira-Ku, Sapporo 062-0052, Japan (Tel: 81-11-852-8866; Fax: 81-11-852-8194; Email: yadachi@sapmed.ac.jp)

© 2013, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(13)60015-6

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Melanoma in the ampulla of Vater

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International (HBPD INT)

- Salvage living-donor liver transplantation to previously hepatectomized hepatocellular carcinoma patients: is it a reasonable strategy?

- Clinical operational tolerance in liver transplantation: state-of-the-art perspective and future prospects

- Radiologic-histological correlation of hepatocellular carcinoma treated via pre-liver transplant locoregional therapies

- Outcomes of side-to-side conversion hepaticojejunostomy for biliary anastomotic stricture after right-liver living donor liver transplantation