Outcomes of side-to-side conversion hepaticojejunostomy for biliary anastomotic stricture after right-liver living donor liver transplantation

2013-05-22

Hong Kong, China

Outcomes of side-to-side conversion hepaticojejunostomy for biliary anastomotic stricture after right-liver living donor liver transplantation

Kenneth SH Chok, See Ching Chan, Tan To Cheung, Albert CY Chan, William W Sharr, Sheung Tat Fan and Chung Mau Lo

Hong Kong, China

BACKGROUND:Conversion hepaticojejunostomy is considered the salvage intervention for biliary anastomotic stricture, a common complication of right-liver living donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct anastomosis, after failed endoscopic treatment. The aim of this study is to compare the outcomes of side-to-side hepaticojejunostomy with those of endto-side hepaticojejunostomy.

METHODS:Prospectively collected data of 402 adult patients who had undergone right-liver living donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct anastomosis were reviewed. Diagnosis of biliary anastomotic stricture was made based on clinical, biochemical, histological and radiological results. Endoscopic treatment was the fi rst-line treatment of biliary anastomotic stricture.

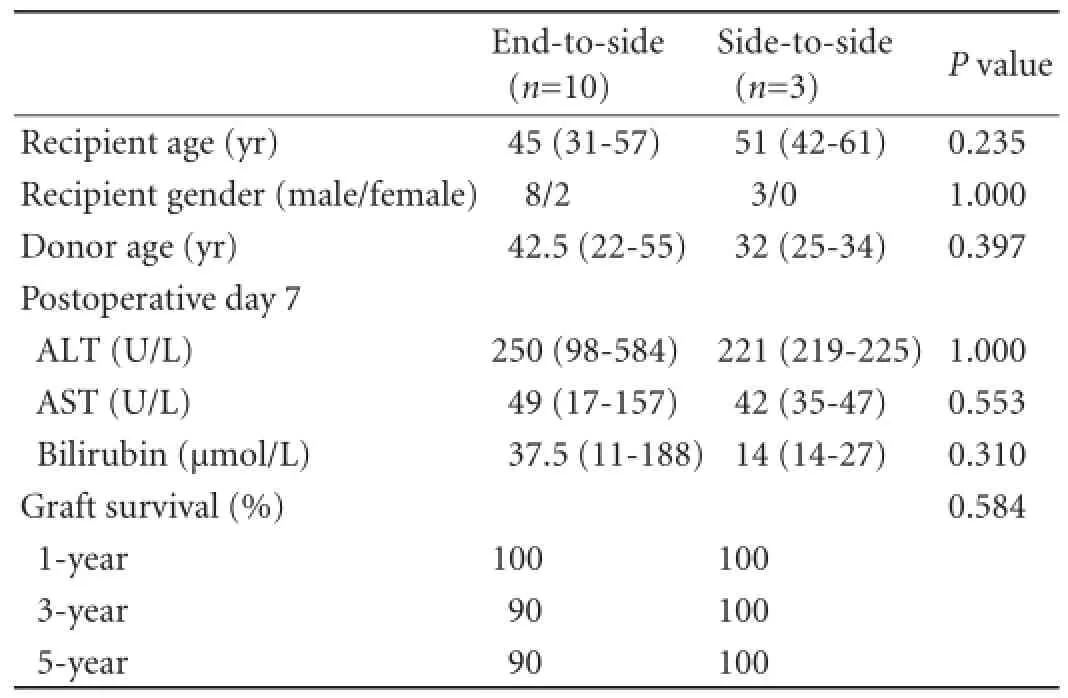

RESULTS:Interventional radiological or endoscopic treatment failed to correct the biliary anastomotic stricture in 13 patients, so they underwent conversion hepaticojejunostomy. Ten of them received end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy and three received side-to-side hepaticojejunostomy. In the end-to-side group, two patients sustained hepatic artery injury requiring repeated microvascular anastomosis, two developed restenosis requiring further percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and balloon dilatation, and two required revision hepaticojejunostomy. In the side-to-side group, one patient developed re-stenosis requiring further endoscopic retrogradecholangiography and balloon dilatation. No re-operation was needed in this group. Otherwise, outcomes in the two groups were similar in terms of liver function and graft survival.

CONCLUSIONS:Despite the similar outcomes, side-to-side hepaticojejunostomy may be a better option for bile duct reconstruction after failed interventional radiological or endoscopic treatment because it can decrease the chance of hepatic artery injury and allows future endoscopic treatment if re-stricture develops. However, more large-scale studies are warranted to validate the results.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013;12:42-46)

right-liver;endoscopic treatment; living donor liver transplantation; biliary anastomotic stricture; duct-to-duct anastomosis; hepaticojejunostomy

Introduction

Adult right-liver living donor liver transplantation (RLDLT) is one of the most complicated and technically demanding surgical procedures. It is associated with high morbidity and re-operation rates.[1]With various advances in techniques and management, an excellent graft survival rate of over 90% even in highrisk recipients has been achieved at our center in recent years.[2]However, bile duct complication is still a major hurdle that affects long-term outcomes and quality of life, and is occasionally the cause of graft loss and patient death.

In RLDLT, duct-to-duct anastomosis (DDA) is used more and more often because of potential advantagessuch as shorter operation time, fewer septic complications, better physiologic enteric functions, and easier endoscopic access to the biliary tract,[3]but biliary anastomotic stricture (BAS) is still a challenging problem to deal with after DDA.[4,5]

Conversion hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) is required if endoscopic or radiological treatment fails in treating BAS. Side-to-side HJ may be a safer option after RLDLT as the right hepatic artery is at risk of inadvertent damage during mobilization of the common hepatic duct, and using this technique of HJ can avoid dissection behind the bile duct anastomosis, avoiding handling of the right hepatic artery. However, relevant study is scarce in the literature. This study was undertaken to compare the outcomes of side-to-side HJ and those of end-to-side HJ at our center.

Methods

This study was a retrospective study and required no institutional approval. Prospectively collected data of adult patients (n=402) who had undergone RLDLT with DDA at our center during the period between February 2001 and December 2010 were reviewed. We adopted a standard perioperative management protocol and surgical techniques for donor and recipient operations as previously described.[6,7]T tube and internal stent were not placed routinely after March 2000. Liver graft was prepared at the back table. Hepatic venous outf l ow reconstruction was done as described elsewhere[8]and the hepatic duct was left untouched at all time.[5]Since August 2002, we have been using histidine-tryptophanketoglutarate solution for graft preservation. Before that, University of Wisconsin solution was used. Patients with previous conversion side-to-side HJ who developed re-stenosis were subjected to endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) via the ordinary route (cannulation of papilla at D2 and not intubating the Roux loop). All re-stenoses were at previous conversion HJ sites. No new stricture was found.

Technique of DDA

At the end of implantation when all vascular anastomoses had been completed and hemostasis achieved, DDA was performed. Bleeding points around the hepatic duct of the graft were plicated with fi ne suture. When there was more than one ductal opening adjacent to each other, ductoplasty was performed. The width of the graft bile duct and the recipient bile duct was measured, and when there was discrepancy, the recipient bile duct was partially closed with suture. End-to-end anastomosis was performed with 6/0 polydioxanone continuous suture for the posterior wall. A short segment of cannula (Fr 3.5 Argyle catheter) was temporarily inserted across the anastomosis until anterior wall anastomosis was completed by using 6/0 polydioxanone multiple interrupted sutures. The cannula was removed before tying up of the sutures. After 2001, abdominal drain was not routinely inserted unless the surgeon decided otherwise.

Follow-up and diagnosis of BAS

All patients were followed up at the liver transplant clinic weekly for the fi rst two months after discharge from the hospital, and then with increasing intervals. Liver functions were checked at each visit and signs of biliary stricture, if any, were recorded. On detection of liver function derangement or discovery of clinical symptom (e.g. skin itchiness, jaundice, cholangitis, etc.), Doppler ultrasound of the liver, liver biopsy and radioisotope scan (EHIDA scan) were performed. ERC was performed for patients suspected of BAS. Patients with conf i rmed BAS were treated with endoscopic dilatation with or without stenting and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Conversion HJ was performed when deemed appropriate after endoscopic treatment had failed.

Management of duct-to-duct anastomotic stricture

ERC was our fi rst-line treatment and the operating surgeons were the endoscopists. Every one of them had performed at least 500 cases of ERC previously. All patients were subjected to papillotomy unless there was contraindication. A straight or curved guide-wire (Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) was inserted through the stricture. In diff i cult cases, a Jagwire (Boston Scientif i c, Natick, MA, USA) and a balloon occlusion catheter (Wilson-Cook Medical) were used. After the guide-wire had passed through the stricture, contrast was injected for visualization of the intrahepatic bile ducts to look for stones or strictures. On identif i cation of stricture, a balloon dilator (6-8 mm) (Hobbs Medical, Stafford Springs, CT, USA) was used for dilatation for at least one minute. If there was residual stricture on completion cholangiogram, a plastic stent (Fr 7-10, straight or pigtail, single or multiple) would be inserted across the stricture at the endoscopist's discretion and ERC would be repeated within six weeks for re-dilatation with or without re-stenting. In general, if the stricture could not be opened satisfactorily after fi ve sessions of ERC, radiological or surgical intervention was considered (Fig. 1).

Techniques of end-to-side and side-to-side conversion HJ (Fig. 2)

A Roux jejunal loop of suff i cient length (>60 cm) was prepared using staplers. Side-to-side jejuno-jejunostomy was done using single-layer 5/0 polydioxanone continuous suture and fashioned at least 40 cm from the HJ anastomosis. In both kinds of HJ, choledochoscopy and operative cholangiography were performed to ascertain ductal clearance, and comparison with previous donor cholangiograms was made in order not to miss any ductal anomaly. For end-to-side HJ, the bile duct anastomosis was identif i ed and meticulous dissection at the posterior aspect of the bile duct was done in order to prevent hepatic artery injury. The bile duct was slung and divided transversely above the stricture. For side-to-side HJ, dissection around the posterior aspect of the bile duct was avoided. A longitudinal incision was made at the anterior wall of the bile duct (posterior wall not divided) and the fi brous stricture was divided across (extending caudally for at least 1 cm for a bigger opening). In essence, techniques of both end-to-side and side-to-side HJ were the same except that in side-to-side HJ, dissection at the posterior aspect of the bile duct was avoided.

Fig. 1.Algorithm of treatment modalities for patients with BAS. DDA: duct-to-duct anastomosis; BAS: biliary anastomotic stricture; ERC: endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; HJ: hepaticojejunostomy; PTC: percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography.

Fig. 2.Schematic diagrams (not to scale) of end-to-side and sideto-side HJ. The right hepatic artery (not depicted in the diagram) is behind the native common hepatic duct. Stricture was identif i ed by choledochoscopy and operative cholangiography. Transverse cholechotomy was done (in end-to-side HJ) above the stricture site and a longitudinal incision was made (in side-to-side HJ) at the anterior wall of the bile duct (posterior wall not divided) and the fi brous stricture was divided across.

Both HJ procedures were performed via a retrocolic or preferably retrogastric route, with 6/0 polydioxanone continuous suture for the posterior wall and 6/0 polydioxanone multiple interrupted sutures for the anterior wall.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of categorical variables was performed using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test where appropriate. Non-parametric continuous variables were compared by the Mann-WhitneyUtest and presented as median with range. Survival was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the logrank test.Pvalues of less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically signif i cant. AllPvalues were two-tailed.

Results

Eighty-seven (21.6%) out of the 402 patients had biliary anastomotic stricture. Endoscopic treatment failed to correct the BAS in 13 patients, so they underwent conversion HJ. Ten of them received end-to-side HJ and three received side-to-side HJ. Table shows that the two groups were comparable in many aspects. In the endto-side group, two patients sustained hepatic artery injury requiring repeated microvascular anastomosis, two patients developed re-stenosis requiring further percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and balloon dilatation, and two patients required revision HJ. In the side-to-side group, one patient developed re-stenosis requiring further ERC and balloon dilatation. No reoperation was needed in this group.

Table.Comparison of the end-to-side and side-to-side groups

Discussion

Biliary complications, BAS in particular, once considered as the technical Achilles' heel of liver transplantation,[9]are still a common cause of morbidity and occasionally a cause of mortality. BAS has been reported to be related to many conditions including prolonged cold ischemic time, hepatic artery thrombosis, ABO blood type incompatibility, cytomegalovirus infection, reduced-size graft, use of University of Wisconsin solution, method of biliary reconstruction, and acute cellular rejection.[4,10]The incidence of ductto-duct anastomotic stricture is consistently higher in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) than in whole-liver deceased donor liver transplantation.[11-15]It is postulated that this is related to the blood supply of the anastomosis and often the presence of multiple and small caliber donor ducts. Endoscopic intervention is a measure to treat BAS, but with a reported overall success rate of 40%-60% only.[16,17]Hence surgical salvage is still the last resort.

Langer et al[18]reported the data on conversion HJ from duct-to-duct anastomosis in recipients of deceased donor liver transplantation. The overall successful rate was 76% after a median follow-up period of 33 months, and 46% of all the conversion HJ cases were done by means of side-to-side HJ. There were two patients with bile leak after HJ and two other patients required retransplantation because of secondary biliary cirrhosis. However, similar data in LDLT are lacking in the literature. In RLDLT, the hepatic artery is at a much higher risk since the graft/native right hepatic artery is short and is usually at the back of bile duct anastomosis. In deceased donor liver transplantation, a longer segment of graft celiac trunk is used for anastomosis.

Surgical treatment of BAS may involve end-to-side HJ or side-to-side HJ. There are theoretical advantages of side-to-side HJ over end-to-side HJ. First, it is not necessary to dissect the posterior aspect of the bile duct, avoiding hepatic artery injury which is possible because of the presence of dense adhesions after transplantation. Moreover, future endoscopic procedures are still feasible in case re-stricture develops. However, side-toside HJ is feasible only if the native common bile duct has adequate length and is not stenotic. Moreover, the graft right hepatic duct needs to have a single opening only; this technique is not suitable for multiple ductal openings in the graft. In the present small series, no inferior outcomes were shown when comparing the two techniques, but if the above-mentioned advantages are taken into account, we would suggest side-to-side HJ for patients with BAS after RLDLT. Of course, research involving a bigger number of patients is needed before any def i nite conclusion can be reached. Moreover, because of its retrospective nature, the present study inevitably has potential bias and def i ciency in drawing a solid conclusion.

In summary, despite the similar outcomes, side-toside HJ may be a better option for bile duct reconstruction after failed endoscopic treatment because it can decrease the chance of hepatic artery injury and allows future endoscopic treatment if re-stricture develops. However, more large-scale studies are warranted to validate the results.

Contributors:CKSH designed the study, did the statistics, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. CTT, CACY and SWW analyzed the data. CSC, FST and LCM were responsible for critical revision and approval of the manuscript.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benef i ts in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

1 Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Wei WI, Lo RJ, Lai CL, et al. Adultto-adult living donor liver transplantation using extended right lobe grafts. Ann Surg 1997;226:261-270.

2 Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Yong BH, Wong Y, Lau GK, et al. Lessons learned from one hundred right lobe living donor liver transplants. Ann Surg 2004;240:151-158.

3 Wachs ME, Bak TE, Karrer FM, Everson GT, Shrestha R, Trouillot TE, et al. Adult living donor liver transplantation using a right hepatic lobe. Transplantation 1998;66:1313-1316.

4 Chok KS, Chan SC, Cheung TT, Sharr WW, Chan AC, Lo CM, et al. Bile duct anastomotic stricture after adult-to-adult right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2011;17:47-52.

5 Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Tso WK, Wong J. Biliary reconstruction and complications of right lobe live donor liver transplantation. Ann Surg 2002;236:676-683.

6 Chan SC, Lo CM, Ng KK, Fan ST. Alleviating the burden of small-for-size graft in right liver living donor liver transplantation through accumulation of experience. Am J Transplant 2010;10:859-867.

7 Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL. Technical ref i nement in adult-toadult living donor liver transplantation using right lobe graft. Ann Surg 2000;231:126-131.

8 Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, Wong J. Hepatic venoplasty in livingdonor liver transplantation using right lobe graft with middle hepatic vein. Transplantation 2003;75:358-360.

9 Calne RY. A new technique for biliary drainage in orthotopic liver transplantation utilizing the gall bladder as a pedicle graft conduit between the donor and recipient common bile ducts. Ann Surg 1976;184:605-609.

10 Qian YB, Liu CL, Lo CM, Fan ST. Risk factors for biliary complications after liver transplantation. Arch Surg 2004; 139:1101-1105.

11 Sampietro R, Goffette P, Danse E, De Reyck C, Roggen F,Ciccarelli O, et al. Extension of the adult hepatic allograft pool using split liver transplantation. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2005;68:369-375.

12 Yazumi S, Yoshimoto T, Hisatsune H, Hasegawa K, Kida M, Tada S, et al. Endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation with ductto-duct biliary anastomosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2006;13:502-510.

13 Spada M, Cescon M, Aluff i A, Zambelli M, Guizzetti M, Lucianetti A, et al. Use of extended right grafts from in situ split livers in adult liver transplantation: a comparison with whole-liver transplants. Transplant Proc 2005;37:1164-1166.

14 Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl 2008;14:759-769.

15 Chan SC, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wei WI, Chik BH, et al. A decade of right liver adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: the recipient mid-term outcomes. Ann Surg 2008;248:411-419.

16 Lee YY, Gwak GY, Lee KH, Lee JK, Lee KT, Kwon CH, et al. Predictors of the feasibility of primary endoscopic management of biliary strictures after adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2011;17:1467-1473.

17 Buxbaum JL, Biggins SW, Bagatelos KC, Ostroff JW. Predictors of endoscopic treatment outcomes in the management of biliary problems after liver transplantation at a high-volume academic center. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 73:37-44.

18 Langer FB, Györi GP, Pokorny H, Burghuber C, Rasoul-Rockenschaub S, Berlakovich GA, et al. Outcome of hepaticojejunostomy for biliary tract obstruction following liver transplantation. Clin Transplant 2009;23:361-367.

Received May 11, 2012

Accepted after revision November 6, 2012

See Ching Chan, MS, PhD, Department of Surgery, The University of Hong Kong, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China (Tel: 852-22553025; Fax: 852-28165284; Email: seechingchan@gmail.com)

10.1016/S1499-3872(13)60004-1

AuthorAff i liations:Department of Surgery (Chok KSH, Chan SC, Cheung TT, Chan ACY, Sharr WW, Fan ST and Lo CM), and State Key Laboratory for Liver Research (Chan SC, Fan ST and Lo CM), The University of Hong Kong, 102 Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China

© 2013, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

杂志排行

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Terry's nail:an overlooked physical finding in cirrhosis

- Melanoma in the ampulla of Vater

- Hepatic portal venous gas in pancreatic solitary metastasis from an esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- News

- Drainage by urostomy bag after blockage of abdominal drain in patients with cirrhosis undergoing hepatectomy

- TRAIL-induced expression of uPA and IL-8 strongly enhanced by overexpression of TRAF2 and Bcl-xL in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells