Liu Heung Shing: A Bigger Picture of China

2013-04-29byNiJunchen

by Ni Junchen

When the clouds over the countrys political arena dispersed and the road toward reform and opening-up was paved in the late 1970s, China gradually became one of the worlds largest and most attractive markets as political terms such as“revolution,” “class conflict,” and “politics in command” gradually faded from Chinese daily life. At the time, the country still suffered from material deficiency, the streets were still covered in political slogans, and most people were still dressed in grey or blue uniforms and showed little excitement on their faces. However, the desire for individual emotions and lifestyles was already growing, and the nation was coming out of the shadows.

To the outside world, China remained mysterious because so little information had emerged about the Eastern country for such a long time. Chinas amazing social transformation and reform werent exposed until 1979, when the country began welcoming foreign journalists from Western media organizations.

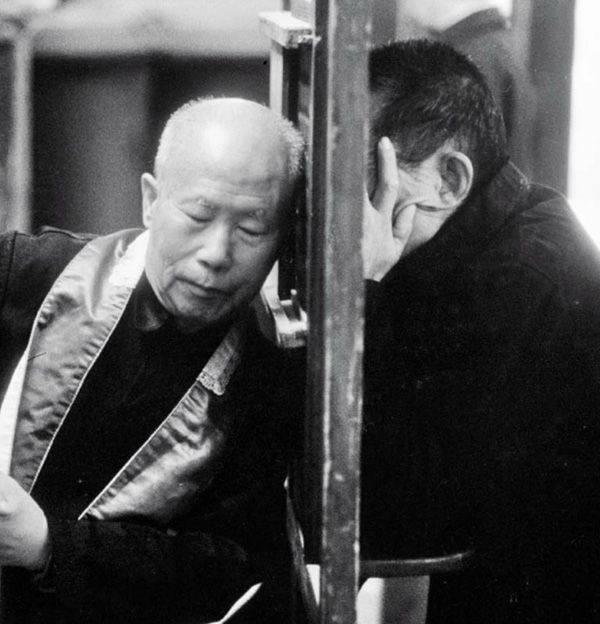

Just at that time, Chinese-American photographer Liu Heung Shing became a journalist to cover China for Time magazine and the Associated Press (AP). Upon learning of the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, he left his post in Europe and headed to Guangzhou,capital of Guangdong Province. In 1979, he was granted a permit to travel around China as a photojournalist for Time. Brimming with curiosity, he comprehensively observed the land with which he was both familiar and unfamiliar. His multicultural background and unique sentiments as a young artist bestowed him deep insight into the subtle changes happening in Chinese society. He zoomed in on China of the post-Mao era.

Liu captured students wearing red scarfs and lifting their fists in a performance denouncing the “Gang of Four,” and teachers joining students in rehearsing Chopin in front of a gigantic sign carrying political slogans in a conservatory. He snapped images of a couple hugging and kissing on a park bench, French designer Pierre Cardin adjusting the collar on a Chinese male model, and a young man in a military coat drinking Coca-Cola in the Forbidden City. Within a few years, the images testifying to the tremendous political and economic changes China was undergoing spread around the world. In fact, Liu contributed half of all news photos related to China printed in Western newspapers and magazines during the era. Chairman Mao was a common subject in Lius photographic work – whether in portraits, souvenir badges, statues, or slogans. His photography has long been acclaimed for its revelations of the nature of the day: Political elements deeply intervened in trivial, ordinary lives of individual people, and individualism gradually replaced collectivism over the decades of reform and opening-up.

In 1983, his album, China after Mao: 1976-1983, a collection of 100 photos taken during those years, was published by Penguin Group. At the end of July 2013, a solo exhibition titled “China Dream, Thirty Years: Liu Heung Shing Photographs” opened in Shanghai, of which two thirds of the images on display come from China after Mao. The images represent the first peak of Lius career, but more importantly carry profound historical value. Just as Fox Butterfield, Beijing bureau chief for The New York Times, commented, “Each photograph states a cold hard fact; he reveals more truths about China than the many volumes of romantic pictures by famous travelers visiting the Peoples Republic. Instead of a postcard version of China, Liu gave the world an incisive, moving and realistic portrait by a genuine artist who is deeply committed to the Chinese people.”

At the end of 1991, as an AP photojournalist stationed in Moscow, Liu snapped the historic moment when Mikhail Gorbachev announced the collapse of the Soviet Union, which won the photographer a Pulitzer Prize the following year. Since the mid-1990s, Liu has been living in Beijing. In recent years, he has been committed to publishing three albums: China, Portrait of a Country, Shanghai: A History in Photographs 1842-Today, and The Road to 1911: A Visual History. Whether through solitary newspaper images or comprehensive albums, Liu hopes to portray a bigger China through his work. As he said, “We cannot stop observing China.”

China Pictorial (CP): The theme of your exhibition “China Dream, Thirty Years” tracks the transformation “from collectivism to individualism.” Is that the greatest change to happen to China over the past three decades?

Liu Heung Shing: Due to its reform and opening-up, China has witnessed tremendous change in both social phenomena and lifestyles. For instance, entertainment, such as spring outings and balls, were previously all organized. In the past, it was commonplace to see student volunteers cleaning streets and factory workers studying politics. At the time, individual consciousness was subject to a certain collective awareness. Now, such phenomena are already rare. The changes of the times are reflected in everyones face, body language, and clothing. I try to document those changes with photographs.

CP : You often declare yourself a traditional photojournalist. What do you mean by the word “traditional”?

Liu : For a traditional photojournalist, the employer gives you considerable time and freedom to do your job. Even before the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the United States, Time magazine already opened an office in Beijing. At the time, both Time and AP dispatched senior reporters to work overseas, and they did not confine journalists to designated tasks, but allowed the latitude to report whatever they thought interesting. Unfortunately, I was perhaps part of the last generation to enjoy such a working environment.

Today, due to the impact of online media, the traditional business mode of print media is broken. Major newspapers and magazines revenue and circulation continue declining. The number of journalists deployed abroad by major media organizations is also decreasing. In the internet era, news arrives faster, but its mostly in the form of messages transmitted from one person to another, rather than in-depth reports that seek truths. Media operations have changed. Without spending the time to read and think, one cannot gain real insight into society or its people. Early in my career, I was lucky to spend five years observing China. After the death of Chairman Mao, China began to embark on reform and opening-up. As Chinese people began to feel the urgency to reform, the nation shocked the world. So, what makes China special and what is unique about its society and economy? I hope that my work reflects social details, as well as the road that China has traveled. We cannot understand photography from a narrow perspective. Only work that can inspire emotional and ideological resonance is exciting.

CP : Chinese painter and critic Chen Danqing once named you along with Henri Cartier-Bresson when lamenting the only “outsiders” to ever produce true, accurate images of China over the past century. What do you think of the term “outsiders”?

Liu : Many world-renowned photographers have taken photos of China, but my work differs from any others. For instance, Marc Riboud and Bresson both upheld the elite mindsets and cultural philosophy that the French maintain, and their work mirrors a French point of view. My work is closer to ordinary Chinese people. Due to my Chinese origins, Chinese people behave differently in front of my camera than they would with a Western photographer. Many Chinese artists have studied abroad, but we cannot call them outsiders. My veins have Chinese blood. Compared to people from Hong Kong and Taiwan, I understand and observe the Chinese mainland in a different way. As British art critic Karen Smith said, I am not an outsider and embrace a deep affection for the “Chinese dream.”

CP : Early Chinese photographers were deeply influenced by traditional Chinese culture. For example, the generation of photographers including Chen Fuli preferred to capture the aesthetic bonds between man and nature in their work. You studied traditional Chinese painting when you were young, but your early photographic work still depicts the aesthetic relationship between people. Where did such a Western mentality come from?

Liu : Traditional Chinese culture advocates the role of individuals being minimized as much as possible. In many Chinese paintings, nature is monumental, while the individual human is tiny. In terms of getting things done, Chinese people believe that taking a step backwards is necessary to move forward, while Westerners like to hold their ground and prepare to attack, stressing the role of individuals. Western religions highlight the relationship between man and God. In addition, Westerners focus on details, while Chinese tend to view the world from a macro perspective.

A persons values are impacted by several combined factors. I express my views about China and its people with my photography– from a perspective different from any other Chinese or Western photographer. I would not have noticed the subtle changes in New China had I not lived in Fuzhou from age two to nine. I had zero Western life experience during the period when my personality was formed. My early life in China helped me understand the certainty of Chinas social system. Meanwhile, my life experience in the United States and Europe exposed me to the influence of Western humanism.

CP : Your early work focuses on ordinary people in the streets of New York, which seems inspired by the Western education you received – paying attention to the weak. Journalists and photographers must focus on the unfortunate. But why did so many stars and celebrities begin appearing in your work after the 1990s?

Liu : I didnt only photograph celebrities in the 1990s. In those days, I took many photos in Guizhou Provinces Liupanshui, one of the poorest places in China. The reason some notice the celebrities in my work is because in this era, stars and celebrities began getting more attention. I never stopped paying attention to what is happening with people across every social stratum.

CP : In recent years, you have been committed to compiling historical photographic and video records rather than taking new pictures. What do you think China can do in terms of historical photographic and video record conservation and compilation?

Liu : China needs to do a lot to conserve and compile such historical records. In 2010, when I was hired to compile a picture album for Shanghai, all the material provided by the local government depicted skyscrapers and other achievements in urban construction, without a single photo depicting Shanghai residents. What is a city without its residents? When I compiled The Road to 1911: A Visual History, every photo provided by major Chinese archives was a reprint of poor quality. It was Jardine Matheson company that provided me with the rare engraving of the signing ceremony of the Treaty of Nanking. I had it re-photographed to the optimal quality. We keep saying that China endured a century of humiliation, but few historical photographic records remain to depict the details of how this happened. This isnt the serious attitude we should have about history.

Fortunately, improvements have been made in this respect, but much still remains to be done.