叶廷芳:译介卡夫卡

2012-04-29巫少飞

巫少飞

在摸索的痛苦中,他发现了同样浸润在痛苦中的卡夫卡;通过译介这位西方现代派文学宗师的作品,显示了自己的艺术慧眼和翻译思想。他就是浙江衢州籍学者叶廷芳。

人有病,天知否?

在北京叶廷芳家中,我迟疑地盯着他左臂的空袖管,试图找到某种关联:这位身体残疾且多病的学者是如何与“现代艺术的探险者”卡夫卡联系起来的?而我之所以迟疑,是因为过多地强调叶廷芳的残疾,可能会掩盖他真正的精神探索。

儿时的过往细事,可能是未来生命的某些隐性征兆。当卡夫卡觉得自己在家里“比一个陌生人还要陌生”,当卡夫卡的事业、爱好不能被家人及同时代所理解时,许多年后,叶先生说:“我的陌生,也是一种‘异化。在三个男孩子中,因为比较聪明,父亲很喜欢我。但是,我的手臂受伤后,从家里的希望变成家里的累赘。这样,他的态度就发生改变,不是更加爱护我,而是把我当作负担,好像给他丢了脸。他的恼怒和痛苦经常会表现出来,使我在他的面前总是战战兢兢。”

以后,叶廷芳成为译介卡夫卡于中国学界的第一人时,与卡夫卡的“精神相遇”不能不说是一种契机。所不同的是,叶廷芳把这种精神提升到人类的自省与批判世界的途径。

译介卡夫卡

叶廷芳生于1936年,上世纪50年代上衢州一中,后入北京大学学习德语。

“文革”前一两年,有一系列‘黄皮书,如迪伦马特的《老妇还乡》、卡夫卡的《审判及其他》、塞林格的《麦田里的守望者》等,以‘供内部参考的方式出版。”叶先生回忆:“那时,我奉命编辑一个内部的‘文艺理论译丛,主要介绍西方的现代派文学,以及一些有代表性的文学的争论或评论。”

1972年,叶廷芳在北京外文书店的仓库里发现了正被廉价清理的前民主德国出版的《卡夫卡小说集》,那时他就萌发了从德文翻译的念头,但当时的政治环境,使他无奈地搁置译书的计划。

1978年,叶廷芳终于有机会实现自己的宿愿。他一边翻译卡夫卡作品,一边著文介绍卡夫卡。

翻译之初,叶廷芳多半出于自己的艺术兴趣和爱好,还认识不到卡夫卡在德语界乃至世界文学中的崇高地位;随着研究工作的深入,他充分认识到卡夫卡是“现代艺术的探险者”。不久,当叶廷芳听说卡夫卡的威望已超过被视为20世纪德语文学泰斗的托马斯·曼时,他决定全身心投于卡夫卡作品的翻译和研究。

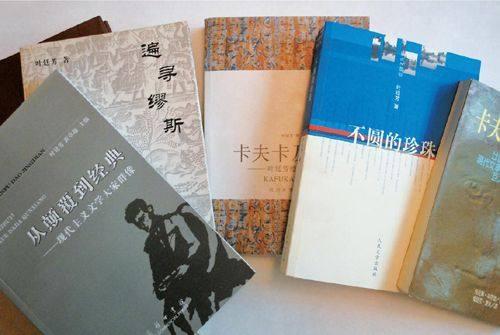

迄今,叶廷芳有30余种卡夫卡研究著译,其中包括主编并参与翻译《卡夫卡全集》、选编研究资料集《论卡夫卡》。卡夫卡对中国文学创作的影响不小,例如,作家余华就曾感叹:“原来也可以(如卡夫卡)这样写小说。”

发现“悖谬”

在当今中国,迪伦马特已成为作品上演率最高的外国剧作家之一,而最早引进他的就是叶廷芳。“上世纪70年代末期,人民文学出版社看到我的第一个译本《物理学家》,就主动约我翻译《迪伦马特喜剧选》。我……于上世纪80年代去了瑞士迪伦马特家中拜访了他……上世纪90年代,拥有迪伦马特全部版权的苏黎世第奥根尼出版社一口气送给我56本迪伦马特的书和有关迪伦马特的著作,并邀请我赴瑞士访问了4个月。”

“迪伦马特的作品与卡夫卡的作品有着内在的联系,有很多可比性。幸运的是,我很快发现了这两位作家创作的秘诀都是‘悖谬,我花了一些工夫,领悟到这一秘诀的奥秘,并大加宣扬,使国内不少作家受到启悟,创作出了成功的作品。”

叶廷芳深知文学翻译的艰难与奥秘。他说,文学翻译是所有翻译中难度最大的一种,搞文学翻译的至少要过四道关:外语关、知识关、母语关、悟性关。他深谙翻译功夫不在文字转换、而要以文学研究为基础的道理。在翻译时,他诚心向各相关学科专家请教各种科学术语,尤其是对书中的核心概念反复琢磨。他对翻译书名也非常讲究,认为改名绝非随心所欲或者标新立异,而是阐释作品的思想。这种重视研究和思考的治学态度,无疑获得越来越多同行的认同。

当笔者问叶先生属于翻译界的第几代时,他说:“如果说,林纾、严复是(为启蒙的)第一代;鲁迅、郭沫若是(为思想的)第二代;冯至、傅雷是(为文学的)第三代;我大约是(为学术的)第四代吧!”

“我与鲁迅的心是相通的”

1975年,叶廷芳与冯至、戈宝权、陈水宜等专家一起,展开了对“鲁迅与外国文学”课题的研究,并于1977年发表了《鲁迅与外国文学的关系》一文,得到了鲁迅研究学者李何林的高度评价。

叶先生说:“搞‘鲁迅与外国文学那个课题是在没有出路中求出路。那些年我通读了一遍《鲁迅全集》,鲁迅对中国文化的深刻认识和对国民性的解剖,使我深受启发,并引起强烈共鸣,从此我也感觉到‘我与鲁迅的心是相通的,感觉到如鲁迅所指出的,中国需要一批‘大呼猛进的精神界之战士,需要将‘五四的启蒙精神继承下去。这是我开始自我觉醒的契机。”

叶廷芳研究鲁迅,后来也借鉴于卡夫卡。他说,鲁迅时时解剖别人,同时也随时解剖自己;卡夫卡也是一样,他不断地批判世界,也不断地批判自己。一个人,要把这两点结合起来才好。

从书斋到广场

与文学结缘,在叶廷芳的生命历程中,是重要的一部分,但并非全部。作为知识分子和全国政协委员,他积极介入公共事务。叶先生表示:“我关心的社会问题较多,对于计划生育、重修圆明园、保护文物等问题,我都付出过努力,并写了相关提案。”

由于有出国交流的机会,叶廷芳对国外的建筑艺术、城市建设等留心观察,仔细研究。他曾著长文《伟大的首都,希望你更美丽》,分三次被《北京晚报》转载。针对修复圆明园的论调,叶廷芳连续写出了《美是不可重复的》《废墟也是一种美》等文章,从美学角度表明了自己保护历史文化遗产的鲜明态度。

叶廷芳担任中国环境艺术协会理事,以及中国肢残协会副主席、中国残联评议委员会主任等职务,热心为公益事业出力。叶先生表示,只要是社会和人民需要的,都是正业。尽管是非学术研究领域的,也愿意奉献。“本来,兴趣作为自己业余生活的调剂是一种享受。可如今我因为兴趣而自觉不自觉地闯入了好几个领域:戏剧、建筑、艺术,无论开会或著文,都花费了许多时间。而我之所以介入公共事务,是因为知识分子的价值就在于批判精神。”

那军号还在催促我

叶廷芳虽然失去了一条左臂,但丝毫不妨碍他做人的完整。他总是那么积极、乐观,用一种友善宽容的心态面对人生。

叶先生回忆,这最初的因缘是他在衢州读小学时的一堂课上,在回答老师的提问时说,自己长大要“寻找缪斯”。好奇心和艺术天赋,使他对这个从书中读到的词语情有独钟。就此,“寻找缪斯”成了他的情结与基本生存方式。2004年,叶廷芳把自己的散文集定名为《遍寻缪斯》。

叶廷芳读书非常刻苦,为了锻炼意志,中学年代叶廷芳每天都比别人早半个小时起床,不管冬夏,他在操场上都穿着一条裤衩、赤着脚跑步晨练。等同学们都起床了,他又跑到衢州古城墙上练嗓子。当时衢州一中有位老号兵,参加过抗日战争,是从十九路军退役的,工作很认真。每天清晨起床、白天上下课、晚上自修和熄灯睡觉,他都吹起军号。那俨然毋忘家国的求学生活,叶廷芳时时记得。他说:“那军号几十年过去了仍一直响在我耳边,敦促着我勤奋学习、工作,永远进取。”

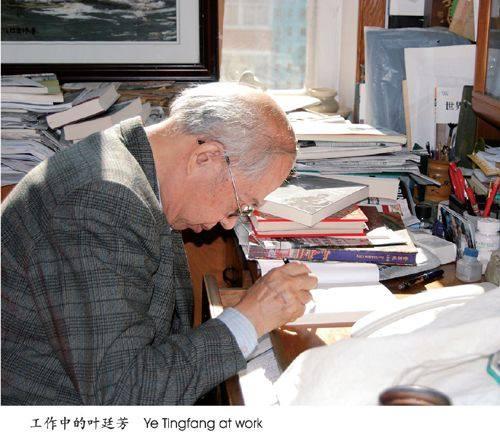

著作等身的叶廷芳,近期被一家研究机构评为“观点被引用最多”的作者之一。走进他家,需要仰视的是他家中上万册藏书,即使是一个小小的阳台,居然也摆了四个书架。他这个在德语文化、美学研究上有创榛辟莽之功的学者,有整整28个抽屉里装着手摘的研究卡片。

叶先生笑称,有一次,他家因电器老化而发生火灾,当时他在楼下,看着浓烟从窗户飘出,他想,如果藏书被烧,自己就去做和尚。所幸家具被烧了许多,书没有被烧毁。

从一个乡间残疾少年,到在国际上享有盛誉的著名学者……叶廷芳左臂空空的袖管,突然成了不断超越的猎猎大旗。

(除署名外,本文照片由作者提供)

Ye Tingfang Introduced Kafka to Chinese Readers

By Wu Shaofei

When it comes to introducing Franz Kafkas works to Chinese readers, Ye Tingfang, a scholar with his ancestral roots in Quzhou, a key city in southwestern Zhejiang Province, stands out as the most important translator of the Czech writer in China.

Born in 1936, Ye Tingfang studied at Quzhou Number One Middle School in the 1950s and studied the German language at Beijing University. He read German authors just one or two years before the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) threw China into chaos. He recalls: “I was instructed to compile a series of translated books on art and literary theories, which touched upon modern literature trends in the west including some representative arguments and reviews. A series of ‘yellow books including those by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Frank Kafka and Jerome David Salinger were translated into Chinese and circulated among a small circle of authorized readers.”

In 1972, he spotted in a warehouse of Foreign Language Bookstore in Beijing “A Collection of Short Stories by Kafka” published by an Eastern Germany publisher. The bookstore put a lot of such books on sales. He bought the book and toyed with the idea of translating it into Chinese, but he put it aside due to the uncertain political circumstances.

In 1978, two years after the Cultural Revolution was brought to end, he set down to translate Franz Kafka (1883-1924). Meanwhile he wrote articles on the Czech writer who wrote in German and recommended him to Chinese readers. At first he translated out of academic purpose and passion, without being aware of Kafkas position in the German-language literature and the worlds literature. As he pushed deep into the world of Kafka, he became fully aware of Kafkas exploration into the modern art. After learning Kafka surpassed Thomas Mann in the German-language literature, he decided to dedicate himself to the translation and study of Kafka. Ye Tingfang was the editor-in-chief of “Complete Works of Kafka” in Chinese and a complete series of research books on Kafka. With his endeavors and many other peoples works, Chinese readers have come to know Kafka and his work. Nowadays, Kafka is an influential figure among Chinese writers. Yu Hua, the author of many important novels, once commented that Kafka opened his eyes to the alternative way of writing novels.

When I first visited Ye Tingfang at his home in Beijing, I saw the empty left sleeve and wondered whether this disability had anything to do with his identification with Kafka. Yes, there was a connection. Ye Tingfang was a smart boy and his father placed great hopes on him. But the boy lost his left arm after an electricity accident. Afterwards, the father felt deeply embarrassed by the disability and his frustration and anguish often surfaced. The junior felt frightened in the presence of his father. He had a troubled relationship with his father. After he started translating Kafka, he felt there was a natural bond between Kafka and him.

Ye Tingfang is also the first Chinese translator that introduced Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921-1990), a Swiss author and dramatist, to Chinese readers. In the late 1970s, Peoples Literature Press commissioned Ye to translate “Selected Comedies of Dürrenmatt”, after seeing Yes translation of “The Physicists: A Comedy in Two Acts”. In the 1980s, Ye visited Dürrenmatt at his home in Swiss. In the 1990s, a publisher in Zurich that owned all the copyrights of Dürrenmatts works gave Ye Tingfang a complete set of 56 books by Dürrenmatt and invited Ye over to do a four-month study in Zurich. Partly thanks to Yes efforts, Dürrenmatt now enjoys a huge popularity with Chinese theatergoers and is one of the most popular foreign playwrights in China.

Literature translation, according to Ye Tingfang, is the most challenging in all kinds of translation. The translator needs to master the source language and the target language, to be a walking encyclopedia on everything concerning his translation, and to posses a power for understanding. In his eyes, if Lin Shu and Yan Fu were the best known representatives of the first-generation translators in modern China, Lu Xun and Guo Moruo the second generation translators, Feng Zhi and Fu Lei the third generation of translators, he thinks he is probably in the fourth generation of translators.

Ye Tingfang is a prolific writer and translator. A research institution recently rates him as one of the most quoted authors. Yes life is one of hard work and research. An avid reader, he has a private library of more than 10,000 books and takes careful notes while reading. An old-generation scholar, he has 28 drawers of meticulously catalogued research cards.