Eucalyptus dunnii and E. saligna for high productivity fibreintroduction and plantations development in Hunan Province

2011-11-15LIBohaiRogerArnold

LI Bohai, Roger Arnold

(Hunan General Station for Popularizing Forestry Science & TechnologyChangsha 410007, China)

EucalyptusdunniiandE.salignaforhighproductivityfibreintroductionandplantationsdevelopmentinHunanProvince

LI Bohai, Roger Arnold

(Hunan General Station for Popularizing Forestry Science & TechnologyChangsha 410007, China)

Most of China’s eucalypt plantation resource is concentrated in warmer southern coastal regions. Relatively small areas have been planted to date in cooler inland areas of southern and southern-central provinces such as Hunan and Jiangxi-areas where selected cold tolerant eucalypts have proven to be both well adapted and very productive. These cooler inland areas have large areas of quality land potentially available for forest plantation development.For cooler plantation environments and particularly for key plantation environments in Hunan Province, climatic data, field trials and plantation experience have shown the most promising cold tolerant eucalypts to beEucalyptusdunniiand selected sources ofE.saligna. In evaluating the performance of these species, it is important that growers and investors look beyond volume and consider wood mass and fibre yield. Research has found thatE.dunniiandE.salignagenerally have significantly higher average wood basic density and higher pulp yield than many of the tropical and sub-tropical eucalypt varieties grown in warmer coastal regions of southern China. Thus, logs ofE.dunniiandE.salignafrom Hunan plantations can be far more profitable fibre sources for pulp mills.

E.dunnii;E.saligna; high productivity fibre; plantation; Hunan

More than 2.0 million hectares of eucalypt plantations have been established to date in China. Most of this resource is concentrated in warmer coastal regions of southern provinces including Guangxi, Guangdong, Hainan, Yunnan and Fujian. Despite this substantial resource of fast growing high yielding eucalypt plantations, China has become, the world’s largest importer of logs and wood fibre. China is also the world’s second largest consumer of paper and paper products and currently accounts for more than 80% of current global annual growth in pulp and paper consumption.

To help address the deficit in forest production, there is great interest in expanding China’s own resource of fast growing high yielding plantations and particularly eucalypt plantations. Some of largest areas of lands potentially available for such plantation expansion, which are suitable for eucalypts, are found within cooler regions of some southern provinces such as Hunan. However, attempts to directly transfer high quality eucalypt germplasm (e.g. hybrid clones ofEucalyptusurophylla×grandis) from the warmer coastal areas to such cooler regions have often met complete failure. Most of the tropical and sub-tropical eucalypts which are the basis of productive plantations in warmer regions such as Guangdong, Hainan and southern Guangxi are ill adapted to frequent winter frosts and cold events with temperatures down to -8 ℃ or lower that can be experienced in Hunan and adjoining inland provinces[1].

1 The Hunan environment

In southern and western Hunan elevations can range up to 1 800 m above sea level. However, three quarters of Hunan province lies at elevations below 500 m asl and it is generally these areas that are of particular interest for eucalypt plantation development.

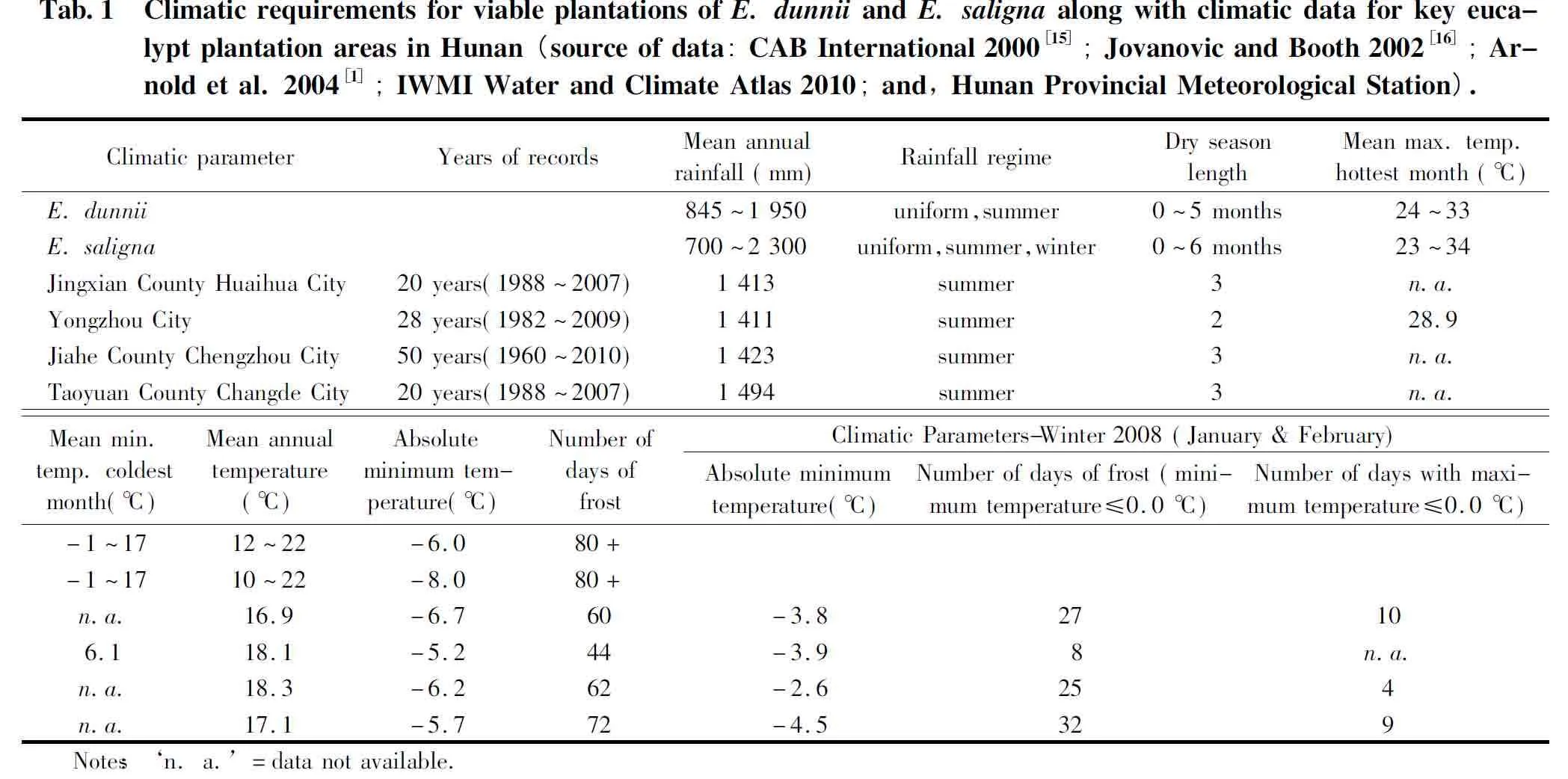

Hunan’s climate can be broadly categorised as ‘humid mesothermal’ and is characterised by extremes and contrasts. In winter, there are frequent winter frosts with occasional advective freezes and temperatures (in western and northern Hunan) down to absolute minimum temperatures of -10℃ or lower. Mean daily maximum temperatures in January generally range between 4℃ and 12℃, and mean daily minimum temperatures generally below 6 ℃. Hunan summers feature persistently high temperatures combined with high humidities; mean daily maximum temperatures in July generally exceed 30℃. The climatic parameters for some of the key potential areas for eucalypt plantation areas in Hunan are summarised in Table 1.

In the north of Hunan there are an average of 100 frosts a year with minimum temperatures for January down to -10℃, whilst in southern Hunan the average number of frosts per year is generally around 60 with minimum temperatures down to -6℃to -8℃[2-3]. As well as frequent frosts, occasional more severe freezes are experienced such as one in December 1999 when temperatures fell rapidly to below -8℃ in areas around Chengzhou and Yongzhou.

In Hunan, rainfall generally decreases from south to the north with southern areas receiving more than 1600 mm per annum and many central parts receiving around 1 400 mm per annum. There is a peak of rainfall between April and June which is frequently followed by late summer drought.

In general, soils in the hilly and mountainous areas of Hunan are predominantly red soils whilst most of lowlands have alluvial soils brought down by the province’s many rivers[3-4]. Indeed most of the province lies within China’s ‘red soils’ region; south central China’s red soils are so named due to their characteristic red or yellow subsoil colours[5]. They are tentatively classified as red dermosols or yellow dermosols in the Australian Soil Classification System[6-7]. Nutrient availability is considered to be the most severely limiting soil factor for the productivity of eucalypt plantations in such areas. Low available levels of the nutrients N and P are commonly found in red soils considered for eucalypt plantation areas across Hunan[8-9]. Other nutrients including potassium, magnesium and sulphur as well as various trace elements are also deficient on many sites. However, despite their nutrient limitations most sites considered suitable for eucalypt plantation development in this region generally have well-structured soils with negligible limitations to effective root depth and are easily penetrated by tree roots. Hence their physical structure is imminently well suited for establishment of productive eucalypt plantations, given carefully nutritional management[7,9].

Detailed reviews and discussions of the soils of eucalypt plantations and potential plantation sites in Hunan and other cooler regions of south central China are provided by Laffan[7,9,10]and Baker et al[8].

2 Introduction of eucalypts to Hunan

It is believed eucalypts were introduced into Hunan in about 1926[11]. However, it was not until the 1950s and 1960s that the province undertook extensive eucalypt planting programs. Forestry, railway and road departments carried out most of these early plantings along railways, roads and other corridors. These plantings used a wide range of species and seed sources but primarilyE.citriodoraandE.exserta, which thrived in the warmer coastal areas of more southern provinces. Such species were poorly adapted to Hunan’s testing environment and there were widespread failures[2]. However, investigations in 1986 revealed that some eucalypts from the early plantings had managed to survive and prosper. Most common amongst the surviving species wereE.camaldulensis,E.robustaandE.botryoides. Of these, the most productive and best adapted seemed to beE.camaldulensis; in 2002 some of the 40-year-old trees (or older) averaged over 25 m in height and up to 63 cm in diameter at breast height[11].

Since the mid 1990s, Hunan Forest Department has developed a more scientifically based domestication and testing program for eucalypts and has established many trials and pilot scale plantations throughout the province. Then in 1999 Hunan province joined a major Chinese-Australian collaborative research project known as the‘Cold Tolerant Eucalypt Project’. This project saw the introduction of more than 30 species, 100 provenances and numerous families of cold tolerant eucalypts for field testing in Hunan.

When Hunan joined the Cold Tolerant Eucalypt Project in 1999, the total area of plantations in the province was very limited-estimated to have been less than 500 hm2. However, based on successes demonstrated by the Project, the area of cold eucalypt plantations in Hunan has increased rapidly in recent years and is now estimated to total more than 50000 hm2(statistics from Hunan Provincial Forest Department.).

3 Adaptation

In Hunan and other cooler areas of southern China the eucalypt species which have generally shown the best adaptation, growth and yields across a large number of trial sites areE.dunniiandE.saligna[1].

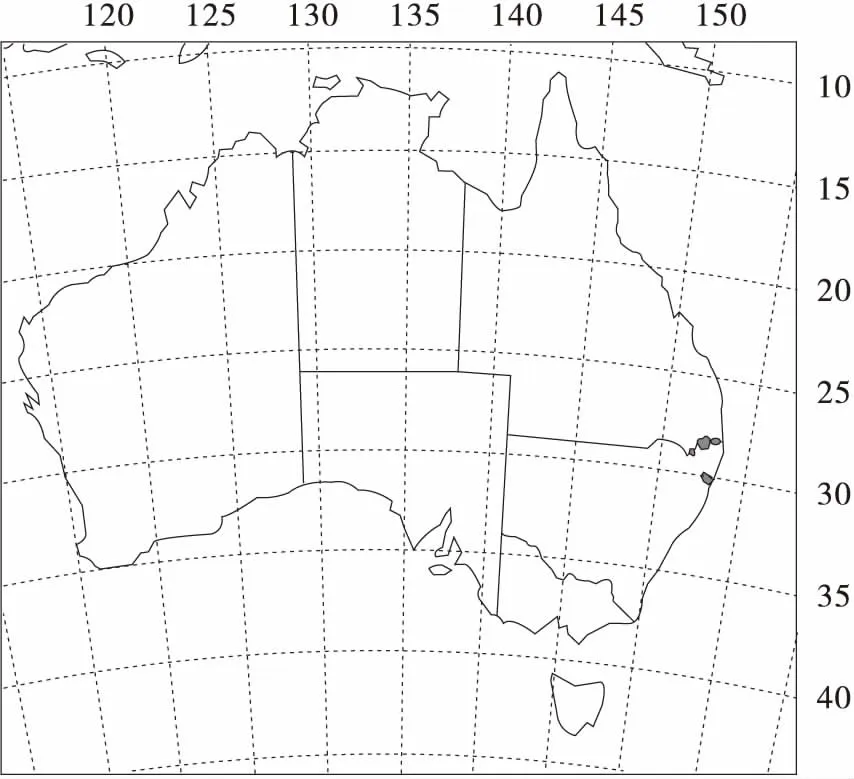

E.dunniicomes from a very restricted natural distribution. It is native to Australia where it is natural range is limited mainly to two small, disjunct locations in the Moleton-Kangaroo River area of New South Wales, north-west of Coffs Harbour (30°S), and in the Border Ranges of New South Wales and Queensland (about 28°S)-see Figure 1. Within these two populations, the species’ distribution is not continuous; it occurs in disjunct communities varying in size from several up to more than 200 hm2. Several isolated small stands also occur just south of the Border Ranges in the Richmond Range area on the Queensland-New South Wales border[12].

Fig.1 Natural distribution of Eucalyptus dunnii, based on Eldridge et al[13].(1993).

E.salignais native to Australia’s east coast and nearby ranges with a broad latitudinal range from 36°S up to 24°S. This range extends from around Batemans Bay in southern New South Wales to around Maryborough in south-eastern Queensland (Figure 2). Then further north there are some isolated, disjunct occurrences on coastal and inland higher elevation areas including Kroombit Tops, the Blackdown Tablelands and Consuelo Tablelands[14]. On higher elevation sites within its natural distribution,E.salignacan experience winters with frequent frosts and minimum temperatures down to -10℃ or lower.

In China and particularly Hunan,E.dunniihas generally shown excellent stem form and adaptation, including very good cold tolerance, drought tolerance and tolerance of high summer humidities. It has also shown the fastest growth rate in numerous trials at lower elevations (<1000m asl) across cooler environments of southern China. In several trials in Hunan, including ones at Chengzhou, Hengyang, Daoxian and Shuangpai, it performed well whereE.grandisand many other eucalypt species failed totally due to cold and/or drought[1]. Some olderE.dunniiplantings (established in about 1991) in northern central Hunan are known to have survived several severe cold events, with temperatures as low as -10℃, with no significant damage.

Fig.2 Natural distribution of Eucalyptus saligna, based on Doran (2009)[14].

E.salignahas also demonstrated good cold tolerance and adaptation across more southern provinces of China, including in Hunan. Selected provenances of this species have shown far superior cold tolerance toE.grandisand in some trials its growth has matched or even exceeded that ofE.dunnii. Overall though, trial results have indicated it may have somewhat lower productivity than the latter species, but this may be due to provenance variation-within its long geographic range there is significant variation between provenances in both adaptation and growth potential[14-15]. However, one limitation of the species is that the best provenances of E. saligna for south central China are still uncertain; most of theE.salignaprovenance and provenance-family trials established in China to identify its best natural provenances are still relatively young.

To understand the potential of bothE.dunniiandE.salignato adapt to Hunan environments, the climatic requirements for productive plantations of both species along with the climatic parameters for four key potential eucalypt plantation areas in this province are shown in Table 1. As it is usually extreme events that determine the success or failure of plantations, annual absolute maximums and minimums are also presented graphically for these four key areas, for periods of between 20 to 50 years up to 2009, in Figure 4 along with adaptive limits forE.dunnii.Winter frost and cold are key limiting factors to domestication of eucalypt species in Hunan is (and hence key adaptive parameters warranting careful attention). Indeed, winter cold is considered by some to be the biggest obstacle for expansion of commercial eucalypt plantations in Hunan. However, Table 1 and Figure 4 clearly show that the key Hunan plantation environments are within the adaptive limits of bothE.dunniiandE.saligna. Whilst the lower absolute minimum temperatures experienced periodically, such as in 1991 and 1999, were close to the limits of these species especially forE.dunnii, no overly serious problems would have been encountered. For hybrids clones such asE.urophylla×grandisfrom Guangxi and Guangdong, the situation would have been very different-these have much lower tolerance of sub-zero temperature and severe damage to them would have resulted from frost and cold experienced. In most parts of Hunan, plantations of tropical hybrid eucalypt clones would be unable to survive through a full rotation without experiencing cold well beyond their adaptive limits.

Despite the adaptation and suitability ofE.dunniiandE.salignato many parts of Hunan, severe meteorological conditions were experienced during winter of 2008 that resulted in damage to large areas of eucalypt plantations in Hunan. However, the damage that occurred during this rare event (estimated to be a 1 in 50 to 1 in 100 year event), was primarily physical rather than physiological. As shown in Table 1 absolute minimum temperatures, number of days of frost and the number of days with maximum temperatures below 0℃ were well within the limits of tolerance for both species in 2008. Rather, the damage in 2008 to large areas of plantations of all forest tree species was primarily stem breakage-snow, freezing rain and temperatures lingering around and slightly below 0℃ for several days resulted in ice accumulating in the crowns of many trees to amounts beyond their physical endurance. It is important to understand that this damage was not dependent on species-eucalypts, Chinse fir, pines and even bamboo all encountered the same problems.

4 Growth potential

Data on the growth of selected cold tolerant eucalypt species has been examined by Arnold et al[1]. based on results from a large number of field trials across various southern provinces including Hunan, northern Guangxi, Jiangxi, Yunnan, Sichuan and Fujian.E.dunniiwas found to average 2.1 cm per year in DBH and 2.1 m per year in height based on results from 12 trials.E.salignashowed slightly slower average growth with 2.0cm per year in DBH growth and 1.8m per year in height growth across 8 trial sites. Whilst the growth of bothE.dunniiandE.salignawas somewhat lower than that ofE.grandison some of the milder of these sites, it is important to note thatE.grandishas failed totally in many trials (due to inadequate cold tolerance) on colder sites whereE.dunniiandE.salignahave proved well adapted and high yielding.

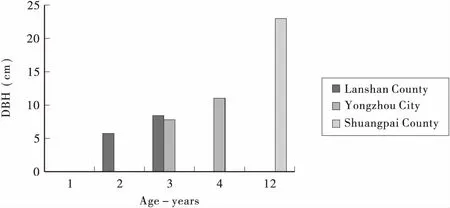

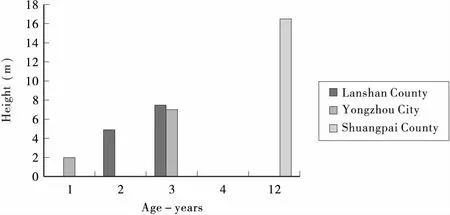

More recent trials ofE.dunniiin Hunan have included two large provenance-family trials established at Lanshan County and Yongzhou in 2004. The DBH and height growth of the best provenances/seed sources in these trials up to age years, along with the growth ofE.dunniiin an older species trial at Shuangpai is shown in Figures 4a and 4b. At approximately age 3 years the better seed sources had average DBHs and heights of nearly 8.5 cm and 7.5 m respectively at Lanshan and 7.8 cm and 7.0 m respectively at Yongzhou (Hunan Forest Department, unpublished data)-this equates to growth rates of up to 2.8 cm per year in DBH growth and 2.5 m per year in height.

To examine the yield and productivity trends over time ofE.dunniiplantations growing in Hunan, more detailed studies were carried out in a trial planting located in Shuangpai County of Youngzhou city, Hunan Province (latitude 25°33′44″ N, longitude 110°58′46″ E, altitude 220 m asl). This trial plantation was established in 1996, and growth data were obtained at two year intervals up to age 12 years. The patterns of tree growth revealed from this work are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 5.

In theE.dunniiat Shuangpai County DBH increased very rapidly during the early years with a peak in increment occurring at around age 6 years (Table 2). Beyond age 10 years, DBH growth slowed considerably. In contrast to DBH, height increments showed greater fluctuations with peaks in height increment at around age 2 years and again at around age 8 years-this fluctuating pattern of height growth may have been in response to annual variations in weather, including rainfall.

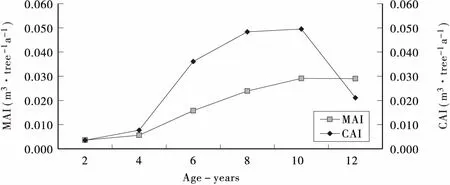

Despite the variations in DBH and height development across the years, the patterns of MAI and CAI found at Shuangpai have been quite regular (Figure 5) and generally Patterns of CAI and MAI can be used to determine rotation ages appropriate for maximising volume productivity-the optimum rotation being considered as the age at which peak MAI is achieved[17]. Based on the growth at Shuangpai, it seems that a rotation of around 10 years would enable site volume productivity to be maximised. However, more data is now needed fromE.dunniitrials and plantations elsewhere in Hunan to verify this trend and make definite recommendations in regard to rotation lengths for eucalypt plantations across this and adjoining provinces.

Tab.1 ClimaticrequirementsforviableplantationsofE.dunniiandE.salignaalongwithclimaticdataforkeyeucalyptplantationareasinHunan(sourceofdata:CABInternational2000[15];JovanovicandBooth2002[16];Arnoldetal.2004[1];IWMIWaterandClimateAtlas2010;and,HunanProvincialMeteorologicalStation).ClimaticparameterYearsofrecordsMeanannualrainfall(mm)RainfallregimeDryseasonlengthMeanmax.temp.hottestmonth(℃)E.dunnii845~1950uniform,summer0~5months24~33E.saligna700~2300uniform,summer,winter0~6months23~34JingxianCountyHuaihuaCity20years(1988~2007)1413summer3n.a.YongzhouCity28years(1982~2009)1411summer228.9JiaheCountyChengzhouCity50years(1960~2010)1423summer3n.a.TaoyuanCountyChangdeCity20years(1988~2007)1494summer3n.a.Meanmin.temp.coldestmonth(℃)Meanannualtemperature(℃)Absoluteminimumtem-perature(℃)NumberofdaysoffrostClimaticParameters-Winter2008(January&February)Absoluteminimumtemperature(℃)Numberofdaysoffrost(mini-mumtemperature≤0.0℃)Numberofdayswithmaxi-mumtemperature≤0.0℃)-1~1712~22-6.080+-1~1710~22-8.080+n.a.16.9-6.760-3.827106.118.1-5.244-3.9 8n.a.n.a.18.3-6.262-2.6254n.a.17.1-5.772-4.5329 Notes:‘n.a.’=datanotavailable.

Fig.3 Absolutemaximumandminimumtemperaturesbyyearfrom1960to2010forfourkeyareasforeucalyptplantationde-velopmentinHunan—YongzhouCityinsouthernHunan,JiaheCountyofChengzhouCityalsoinsouthernHunan,TaoyuanCountyofChangdeCityinnorthernHunan,andJingxiancountyofHuaihuaCityinsouth-westernHunan.Note:AdaptiveclimaticlimitsofE.dunniiaredepictedbygreenshadingwithabsolutemaximumandminimumlimitsshownasreddottedlines.

Fig.4a Diameter at breast height over bark (DBH) of the best seed sources/provenances of E. dunnii at three sites in Hunan at ages ran-ging from 2 to 12 years.

Fig.4b Height of the best seed sources/provenances of E. dunnii at three sites in Hunan at ages ranging from 1 to 12 years.

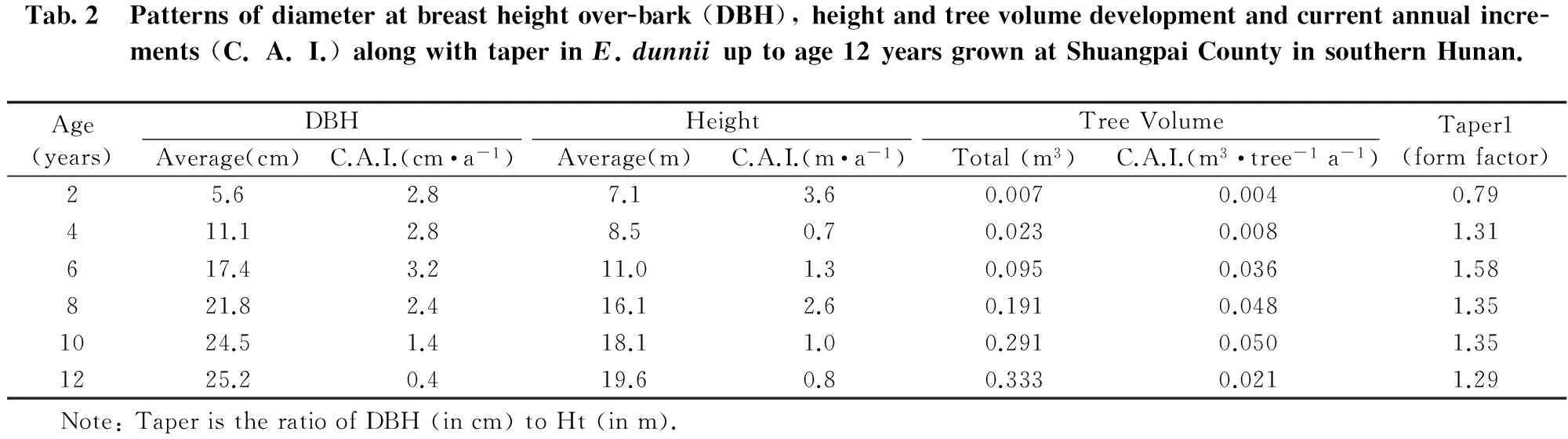

Tab.2 Patternsofdiameteratbreastheightover-bark(DBH),heightandtreevolumedevelopmentandcurrentannualincre-ments(C.A.I.)alongwithtaperinE.dunniiuptoage12yearsgrownatShuangpaiCountyinsouthernHunan.Age(years)DBHHeightTreeVolumeTaper1(formfactor)Average(cm)C.A.I.(cm·a-1)Average(m)C.A.I.(m·a-1)Total(m3)C.A.I.(m3·tree-1a-1)25.62.87.13.60.0070.0040.79411.12.88.50.70.0230.0081.31617.43.211.01.30.0950.0361.58821.82.416.12.60.1910.0481.351024.51.418.11.00.2910.0501.351225.20.419.60.80.3330.0211.29 Note:TaperistheratioofDBH(incm)toHt(inm).

Fig.5 Mean annual volume increment (MAI) and current annual volume increment (CAI) of E. dunnii up to age 12 years at Shuangpai County in southern Hunan.

conform to ‘classical’ yield patterns of fast growing plantations[17]including those of fast growing eucalypt plantations elsewhere in China[18]. Both CAI and MAI increased rapidly in the early years, particular after about age 4 years, and then peaked at around age 10 years. Following the peak, the CAI showed a very rapid decline.

Consistent use of superior provenances or seed sources might considerably lift the average growth achievable in future plantings beyond what has been reported above. Indeed, provenance variations within bothE.dunniiandE.salignaare known to be very important factors in determining both adaptation and productivity[12].

To complement seed source/provenance selection, careful attention must also be given to site selection and to nutritional and silvicultural management. With good site selection, high quality silvicultural management and use of superior seed sources then growth rates achievable forE.dunniishould be markedly higher than the averages achieved in the trials summarised above.

5 True yield-the importance of wood quality

To date, the genetic improvement of eucalypts in China has focused primarily on adaptation and volume growth. However, the true value and profitability of eucalypt plantations over the longer term is determined not just by volume of timber produced but also by the quality of that timber.

Research in China and many other countries has found marked differences between the wood properties of different eucalypt species-these differences have important influences on the relative value of alternative species to both plantation growers and wood using industries. At present, one of the main end product objectives for eucalypt plantations in southern China is pulpwood to supply raw material for pulp mills. For pulping, two of the key wood properties of commercial interest to both plantation growers and the pulp mills are wood basic density and screened kraft pulp yield-pulp mill companies are very concerned about these traits as pulp is sold by weight and not by volume.

Data on key wood properties ofE.dunniiandE.salignaalong with those for a selection of other eucalypts commonly grown in China are given in Table 3. From this, it is apparent that each 1 m3ofE.dunniitimber will be substantially more valuable to kraft pulp mills than that ofE.urophyllagrandis, which in turn will be more valuable than wood ofE.grandis, as the wood mass in these species would be 518 kg per m3, 465 kg per m3and 480 kg per m3respectively. The significance of these differences is compounded by the fact each 1 kg ofE.dunniitimber will be worth more than each 1 kg ofE.grandisbecauseE.dunniihas an average screened pulp yield of 49.6% compared to just 46.0% forE.grandis. Thus, a given volume ofE.dunniiorE.salignatimber will produce far more pulp fibre on average than the same volume of eitherE.urophylla×grandisorE.grandis.

Based on available data it seems that the wood mass and pulp yield ofE.salignawould be even higher than that ofE.dunnii, as shown in Table 3. However, more field sampling is required to confirm the validity of the data presented here forE.saligna’swood properties.

Tab.3 ProductivityandfibreyieldofE.dunniiinHunancomparedtoselectedeucalyptvarietiesgrowninwarmercoastalre-gionsofsouthernChina(sourceofdata:CABInternational2000[15];BalodisandClarke2005[19];ChinaEucalyptResearchCentreunpublisheddata;and,HunanForestDepartmentunpublisheddata).ProductivityWoodbasicdensity(kg·m-3)Screenedpulpyield(%)Pulpproductivityi.e.yieldoffibreperm3(kg·m-3)Scenario1-equalgrowthratesScenario2-equalfibreyieldgrowthrate(m3·hm-2a-1)-fibreyield(kg·hm-2a-1)-growthrate(m3·hm-2a-1)-fibreyield(kg·hm-2a-1)E.dunnii*51849.625725.0642326.16700E.saligna56446.326125.0652825.76700E.urophylla×gran-dis**46549.322925.0573129.26700E.grandis***48046.022125.0552030.36700 Note:*E.dunniidatabasedon12-year-oldtreessampledfromShuangpaicountyinHunan;**E.urophylla×grandisdatabasedonamix-tureofclonesatage5yearsinGuangxi-dataaveragedacross3sites;***E.grandisdatabasedon51/2yearoldtreesatDongmenandsurveyoflit-erature.

Given the important differences between wood properties ofE.dunnii,E.saligna,E.urophylla×grandisandE.grandis, it instructive to consider some scenarios for planning pulpwood production from plantations of these species (see Table 3). The first scenario involves the four species having equal growth rates-on account ofE.dunnii’ssuperior wood properties it will in fact produce 9% more pulp fibre thanE.urophylla×grandisand about 13% more thanE.grandis. LikeE.dunnii,E.salignawill also have superior yield-about 13% more pulp fibre thanE.urophylla×grandisand about 18% more thanE.grandis. In scenario 2, it is assumed that all four species need to produce an equivalent mass of fibre per ha per year-E.dunniican achieve this with about 11% lower volume production per ha than canE.urophylla×grandisand 14% lower volume than canE.grandis. For scenario 2,E.salignacould produce the required pulp fibre with about 12% lower volume production thanE.urophylla×grandisand 15% lower volume thanE.grandis.

Clearly,E.dunniiandE.salignaplantations in Hunan have the potential to produce more profitable logs for pulp companies than do eitherE.urophylla×grandisorE.grandisplantations in warmer regions of southern China. This potential for superior fibre yield per unit volume ofE.dunniiwood should be a major incentive for investment in the establishment ofE.dunniiplantations in Hunan and adjoining cooler regions of southern China.

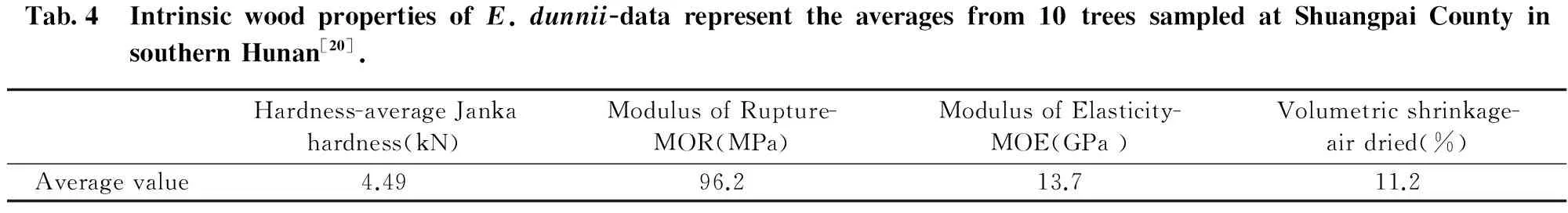

Aside from pulp production, bothE.dunniiandE.salignaare eminently well suited for a range of solid wood applications, including veneers and sawn timbers. For both species their sawn timbers and veneers are well suited to products requiring high quality appearances such as furniture and flooring. Recently, wood properties of importance for such solid wood applications were investigated for 12-year-oldE.dunniitrees from Shuangpai county of Yongzhou city in Hunan province. Timber samples obtain from these trees were analysed by Wood Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Forestry in Beijing-the results from this work are shown in Table 4.

Tab.4 IntrinsicwoodpropertiesofE.dunnii-datarepresenttheaveragesfrom10treessampledatShuangpaiCountyinsouthernHunan[20].Hardness-averageJankahardness(kN)ModulusofRupture-MOR(MPa)ModulusofElasticity-MOE(GPa)Volumetricshrinkage-airdried(%)Averagevalue4.4996.213.711.2

6 Economic feasibility-E.dunnii plantations in Hunan

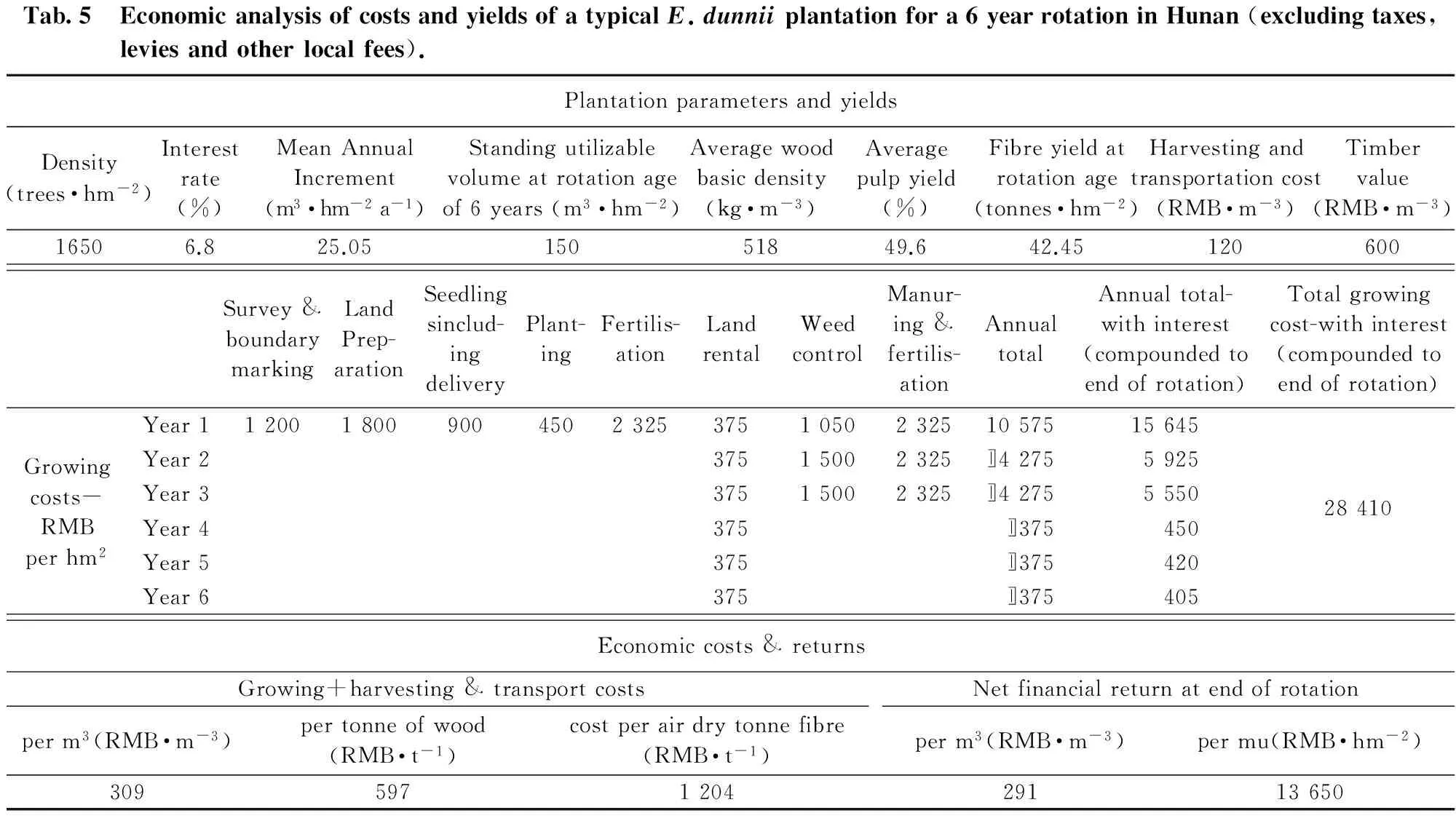

To examine the economic feasibility ofE.dunniiplantations in Hunan-data and key parameters regarding plantation productivities, wood properties and costs obtained from studies in Hunan are summarised in Table 3. The total cost in a first rotation of length 6 years for an averageE.dunniiplantation is currently around RMB 1894 (with interest at 6.8%/year and costs compounded to the end of the rotation). Given an average productivity of 25 m3/hm2/year, the total revenue from sale of timber at the end of the rotation would be around RMB 90000/hm2before costs. After all costs (except taxes, levies and local fees) the net return would be around RMB 43650/hm2. This net return compares favourably with costs and returns of plantations of hybrid eucalypt clones grown in warmer coastal regions of Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan[21].

7 The future

Studies in both Hunan and elsewhere have revealed that important wood properties not only differ among key eucalypt species but also within these species[22-23]. In fact, large heritable differences in key wood properties such as basic density and fibre yield withinE.dunniiand other species create opportunities for genetic improvement of important wood properties as well as volume productivity and hence gains in plantation profitability.

UnfortunatelyE.dunniitree improvement and plantation development in China is somewhat hampered by difficulties of seed production and vegetative propagation. This species generally does not start to flower until age 10 years or more and even once it does start, flowering and seed production can then be light and irregular. In the early 1990s a series ofE.dunniiprovenance-family trials cum seedling seed orchards were established in the north-east of Guangxi Province. However, up until now (age >18 years), very little flowering has been observed in any of these trials. Fortunately though, when planted in some selected environments such as the far south-west of Hunan Province (Huaihua city) and also in central Yunnan Province (Chuxiong City) a more reliable incidence of flowering has been observed. In Huaihua City more than 1000 trees have been observed to flower from as early as age 5 years, whilst in Chuxiong on the Yunnan plateau regular heavy flowering from as young as age 3 to 4 years has been observed.

Tab.5 EconomicanalysisofcostsandyieldsofatypicalE.dunniiplantationfora6yearrotationinHunan(excludingtaxes,leviesandotherlocalfees).PlantationparametersandyieldsDensity(trees·hm-2)Interestrate(%)MeanAnnualIncrement(m3·hm-2a-1)Standingutilizablevolumeatrotationageof6years(m3·hm-2)Averagewoodbasicdensity(kg·m-3)Averagepulpyield(%)Fibreyieldatrotationage(tonnes·hm-2)Harvestingandtransportationcost(RMB·m-3)Timbervalue(RMB·m-3)16506.825.0515051849.642.45120600Survey&boundarymarkingLandPrep-arationSeedlingsinclud-ingdeliveryPlant-ingFertilis-ationLandrentalWeedcontrolManur-ing&fertilis-ationAnnualtotalAnnualtotal-withinterest(compoundedtoendofrotation)Totalgrowingcost-withinterest(compoundedtoendofrotation)Growingcosts-RMBperhm2Year112001800900450232537510502325105751564528410Year237515002325〛42755925Year337515002325〛42755550Year4375〛375450Year5375〛375420Year6375〛375405Economiccosts&returnsGrowing+harvesting&transportcostsNetfinancialreturnatendofrotationperm3(RMB·m-3)pertonneofwood(RMB·t-1)costperairdrytonnefibre(RMB·t-1)perm3(RMB·m-3)permu(RMB·hm-2)309597120429113650

In addition to problems of seed production withE.dunnii, vegetative propagation of this species has very low success rates. World wide huge resources have been invested in trying to develop efficient vegetative propagation protocols for this species, but there has been no real success. In order to facilitate the expansion of profitable plantations ofE.dunniiin Hunan, researchers will need to devise way to propagate the species more easily and/or develop hybrids betweenE.dunniiand some other more readily propagated cold tolerant eucalypts. However, it is important for researchers and growers to understand that hybrids rarely offer anything superior to their parent species with respect to cold tolerance and wood properties. In eucalypt hybrids, most adaptive and wood property traits are generally inherited in an additive manner[24]. Thus hybrids betweenE.dunniiand other eucalypt species would be expected to have cold tolerance, wood density and fibre yield that are intermediate between their two parent species. In order to produce cold tolerant hybrids for Hunan, the selection of both parent species for cold tolerance as well as growth and yield will be all important.

8 Conclusions

It is in Hunan and some adjoining provinces that some of the largest areas available for establishment of new fast growing high yielding eucalypt plantations will be found. In these areas growers can not rely on the clones/varieties and silviculture from warmer southern areas of China; such strategies have often met complete failure in the past. Tropical and sub-tropical hybrid eucalypt clones are not adapted climatically to the cooler environments featuring frequent winter frosts with minimum temperatures of - 5.0℃ and lower.

Trials and plantation experience across a wide range of Hunan sites, complimented by analyses of climatic data, have identified a number of eucalypts species well adapted for establishment of such plantations in cooler environments of this province. The species that has demonstrated the best potential to date isE.dunnii, whilst selected sources ofE.salignahave also shown good potential. With these eucalypt species it is not just their adaptation and volume growth that are important to determining the value of their plantations-there are also important and valuable differences between species in wood properties. Indeed it is noteworthy that the wood properties ofE.dunniiandE.salignastand to make them more valuable for pulp production relative to some of the other key eucalypts grown in China.

Finally it is important to emphasise that it is not just species selection and tree improvement that will be important for cold tolerant eucalypts to be successful. Careful attention must also be given to optimising soil, nutritional and silvicultural management for species such asE.dunniiandE.salignato be successful in Hunan.

9 Acknowledgements

Special acknowledgement is due to our colleagues and other friends in Hunan Forest Department along with the China Eucalypt Research Centre who have done a huge amount of work to encourage development of successful eucalypt plantations in Hunan province.

[1] Arnold, R.J., Luo, J. and Clarke, B. 2004. Trials of cold tolerant eucalypt species in cooler regions of south central China[R]. ACIAR Technical Report No. 57. ACIAR: Canberra: 106.

[2] Turnbull, J.W. Eucalypts in China[J]. Australian Forestry, 44(4):222-234.

[3] Zhao, S. Physical geography of China[M]. Beijing: Science Press; and, New York: John Wiley and Sons. 1986.

[4] Britannica Online. “Guangxi” Encyclopaedia Britannica [EB/OL].

[5] Grimshaw, R.G. and Smyle, J.W. An approach to agricultural development and soil moisture conservation in red soil areas of south China. [C]// Horne, P.M., MacLeod, D.A. and Scott, J.M. (eds.). Forages on Red Soils in China-Proc. of a workshop, Lengshuitan, Hunan Province, PRC. ACIAR Proceedings No. 38, 1991: 74-81.

[6] Isbell, R.F. The Australian Soil Classification[M]. CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne.1996.

[7] Laffan, M. Soils, eucalypts and forest practices in southern China[J]. Forest Practices News 2002, 4(4):3-5.

[8] Baker, T., Laffan, M., Neilsen, W., Arnold, R., Chen, S., Jiang, Y. Xiang, D., Lin, M. and Lan, H. 2003. Correlating eucalypt growth and nutrition and soil nutrient availability in the cooler provinces of southern China. [C]// Turnbull, J.W. (ed.). Proceedings of ‘Eucalypts in Asia’-a symposium held in Zhanjiang, People’s Republic of China, ACIAR Proceedings No. 111. 2003: 161-168.

[9] Laffan, M. Plantation potential of red and yellow soil in southern China-a summary and interpretation of sites and soils inspected as part of ACIAR Project FST/96/125[C]//. Technical Report. Hobart: Division of Forest Research and Development, Forestry Tasmania. 2003.

[10] Laffan, M., Baker, T. and Chen, S. Soils proposed for eucalypt plantations in southern China: properties, distribution and management requirements. [C]// Turnbull, J.W. (ed). Proceedings of ‘Eucalypts in Asia’-a symposium held in Zhanjiang, People’s Republic of China, 2003:154-160.

[11] Lin, M., Arnold, R., Li, B. and Yang, M. Domestication of cold tolerant eucalypts in Hunan Province. [C]// Turnbull, J.W. (ed). Proceedings of ‘Eucalypts in Asia’-a symposium held in Zhanjiang, People’s Republic of China, 2003: 107-116.

[12] Arnold, R., McLeod, I. and Clarke, B. 2009 Eucalyptus dunnii. [C]//Clarke, B. McLeod, I. and Vercoe, T. (eds.). Trees for Farm Forestry: 22 promising species. Publication No. 09/015 Project No. CSF-56A Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation:69-78.

[13] Eldridge, K.G., Davidson, J., Harwood, C.E. and Van Wyk, G. Eucalypt Domestication and Breeding[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1993.

[14] Doran, J.C. Eucalyptus saligna. [C]//Clarke, B., McLeod, I. and Vercoe, T. (eds.). Trees for Farm Forestry: 22 promising species. Publication No. 09/015 Project No. CSF-56A. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), Canberra. 2009: 152-162.

[15] CAB International. Forestry Compendium-a silvicultural reference. Global Module[EB/OL]. Wallingford, UK: CAB International. CD ROM 2000.

[16] Jovanovic, T. and Booth, T. Improved Species Climatic Profiles[M]. RIRDC Publication No. 02/095 (Project No. CSF-56A). Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra. 2002.

[17] Binkley, D., O’Connell, A.M. and Sankaran, K.V. 1997. Stand development and productivity. [C]// Nambiar, E.K.S. and Brown, A.G. (eds). Management of Soil, Nutrients and Water in Tropical Plantation Forests. ACIAR Monograph No. 43. ACIAR, Canberra. pp. 419-442.

[18] Chen, S., Arnold, R., Li, Z., Li, T. Zhou, G., Wu, Z., Zhou, Q., . Tree and stand growth for clonal E. urophylla x grandis across a range of spacings in southern China[J]. New Forests. 2009.

[19] Balodis, V. and Clark, N.B. Pulping and papermaking properties of plantation eucalypts. [C]// Proc. of China’s First International Eucalyptus Pulp and Paper Symposium, Haikou, Hainan, 2005: 244-256.

[20] Thomas, D., Harding, K., Boyton, S., Henson, M., Shen, W., Zhang, Z., Xiang, D., Chen, J., Jiang, X., Yin, Y., Lin, M. and Li, B. Genetic variation in growth and wood quality of Eucalyptus dunnii in southern China[Z]. Unpublished Report. 2009.

[21] Xu, D. Scenarios for a Commercial Eucalypt Plantation Industry in Southern China. [C]// Turnbull, J.W. (ed.). Proc. of ‘Eucalypts in Asia’-a symposium held in Zhanjiang, People’s Republic of China, 2003: 39-45.

[22] Luo, J. Genetic variation of E. dunnii in China[M]. Master of Science Thesis-Nanjing Forestry University.2002.

[23] Raymond, C. A. Tree breeding issues for solid wood production. [C]// The Future of Eucalypts for Wood Products. Proceedings of an IUFRO Conference, Launceston, Tasmania, Australia. 2000: 265-270.

[24] Potts, B.M. and Dungey, H.S. Interspecific hybridization of Eucalyptus: key issues for breeders and geneticists[M]. New Forests 2004: 115-138.

2011-04-24

2011-06-10

李柏海(1970-),男,湖南省洞口县人,中南林业科技大学森林培育学博士;教授级高级工程师,入选湖南省121人才工程人选,全国桉树专业委员会常务理事。主要研究方向:耐寒桉树育种与栽培。

湖南省邓恩桉与柳桉高产纤维材引种培育研究进展

李柏海, Roger Arnold

(湖南省林业科技推广总站, 湖南 长沙 410007)

中国大多数桉树资源主要集中在较为温暖的沿海地区。目前在湖南和江西等华南和中南省份较为冷凉的内陆地区,通过选择一些合适的耐寒桉树品种,种植了一些规模不大的桉树人工示范林,这些示范林显示出了较好的适应性与丰产性。这些较为冷凉的内陆地区有着立地条件较为优越的适合人工林发展的广大林地。对于较冷地区,尤其是湖南省来说,通过分析所有的已建立的田间试验数据、气候资料,以及根据在这些地区桉树人工林培育的历史经验,我们认为邓恩桉与通过选择的部分合适地理种源的柳桉是这类地区最具希望的桉树发展品种。对于林木培育者与投资者来说,评价这些品种的表现,不应该只是局限于木材材积的多少,更应该关注木材质量与纤维产量。研究表明相对在热带与亚热带等华南沿海地区栽培的很多的桉树品种来说,邓恩桉与柳桉的平均木材基本密度与得浆率更高。因此,对于纸浆厂来说,如果利用湖南的邓恩桉与柳桉人工林木材作为制浆原料,将获得更大的利润空间。

邓恩桉; 柳桉; 高产纤维材; 人工林; 湖南

S 792.39

B

1003-5710(2011)03-0005-11

湖南省生态公益林效益监测与评价(2130209)

10. 3969/j. issn. 1003-5710. 2011. 03. 002

(文字编校:杨 骏)

收稿日期: 2011-04-15

修订日期: 2011-05-19