Electoral Choice

2010-10-14ByKERRYBROWN

By KERRY BROWN

Electoral Choice

By KERRY BROWN

Changes are afoot as the British head to the polls

Britain will hold its first election in five years o n M a y 6.And unlike any since the early 1990s, it is very hard to see who might win.Current Prime Minister Gordon Brown of the Labor Party is unpopular and, despite working hard to keep the recession from turning into a depression, is blamed for the huge levels of debt Britain has.

Conservative leader David Cameron,meanwhile, is ahead in the opinion polls, but not by a large enough margin to feel con fi dent that a victory is certain. He is seen as fresh,dynamic and young, but has been accused of lacking substance and having a privileged background that makes it hard for him to relate to ordinary people.

In between is the third party, the Liberal Democrats. Despite good poll results and support from as much as a quarter of the electorate, they remain locked in a “ fi rst-past-thepost” system that means they will never get the number of parliamentary seats their votes would merit.

Elections in the UK, like anywhere else,are about domestic issues. And topmost of these is the economy. The UK is just emerging from six quarters of negative growth.With only 0.4 percent growth at the end of 2009, the recovery, such as it is, is weak.For Labor, government spending needs to continue, and cuts, when they come, must be careful, and phased over a decent length of time. For the Conservatives, it is best to face up to the debt now, and to start to repay it—not least to maintain international con fi dence in the British system. They are proposing immediate cuts. But there is little consensus amongst economists over which side, in the end, is right.

Foreign affairs

What might a Conservative win mean for the UK’s relations with other countries and, in particular, with China? It is not likely that Cameron has thought much about this. As an opposition leader, his main priority in the last few years has been showing the electorate and the Labor opposition that he understands domestic issues, such as taxes, education and social services.

COURTESY OF KERRY BROWN

Foreign affairs, that is, have come a long way down this list. On some foreign policy issues, however, Cameron will almost certainly have to make up his mind quickly—if he gets elected—about what he will need to do. Like previous prime ministers, he will fi nd that foreign affairs will take up more of his time than he would have originally thought.

On involvement in Afghanistan, it is hard to see him making many changes. The UK is very aware that the United States is the dominant partner in this conflict. Downing Street also knows that, having largely withdrawn from Iraq, UK forces in Afghanistan are under even more pressure to contribute,and to help in the surge to contain, and defeat,Taliban forces.

Moreover, as one analyst in London put it earlier this year, “defeat for us and the United States would mean the Taliban sitting in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Kabul.”

And Cameron, despite the big spending cuts he has vowed to make, will find this area will continue to be a huge cost—supporting thousands of British soldiers there with no short-term victory in sight,with casualties continuing to mount. Still,the Conservatives supported the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and military operations in Afghanistan ever since. So a major policy change is not likely.

For Europe, things are different.Historically, the Conservatives have been torn over the UK’s role in the European Union (EU). Edward Heath, a Conservative Prime Minster, was the key person to take the UK into the EU.

But many conservatives are deeply skeptical of what the EU represents. They accuse it of being overly in fl uenced by France and the Germany, of costing the British too much,and of being a huge, Europe-wide bureaucracy—one with powerful, yet unelected bureaucrats taking decision-making powers away from the UK, while trying to build a transnational super-state.

Policy on the EU is the one foreign issue that does have impact in domestic voting intentions. To this end, one smaller party, the UK Independence Party, has complete withdrawal from the EU as its sole stand. But they are likely to do reasonably well in the May elections.

Cameron, if elected, will be faced with three options. He will have to either sound tougher on the EU, and try to extract concessions on how much funds the UK gives to it,and what other benefits it gains. Or he will need to be pragmatic and admit the bene fi ts of membership, keeping things as they are.He might even try to take a more proactive,central role in the EU.

The fi rst will risk alienating important EU partners (the EU is by way and afar the UK’s biggest trade partner). The second will risk alienating many of his own party members, and the voting public. With the third, he will come against some tough French and German resistance. His relations with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, despite both being conservatives,are not good since Cameron authorized his party to withdraw from a coalition of conservative parties at the European Parliament.

Whatever he does, EU policy is going to be one of the biggest problems for Cameron, especially as it looks increasingly likely that economies like Spain and Portugal will need help from European partners in dealing with their huge debts, just as Greece recently did.

Any view in the UK that Britain is paying to clear up the problems of other countries,while still not a member of the euro zone,would be fatal.

With the United States, while Cameron is likely to want to deepen the “special relationship” and stay as close to Washington as possible, there is increasing awareness of how peripheral to the world’s last remaining superpower the UK is.

Indeed, President Barack Obama has even weaker links with the UK than his predecessor George W. Bush. He is returning the United States more and more to a Paci fi coriented, rather than a European-oriented,foreign policy perspective.

Obama’s announced decision not to attend a major EU summit in Spain in May has been interpreted as a further signal that there has been a quiet, but de fi nite downgrading of relations with the whole of the EU.

Trade with China is largely seen positively in the UK, and has attracted far less political flack than in the United States

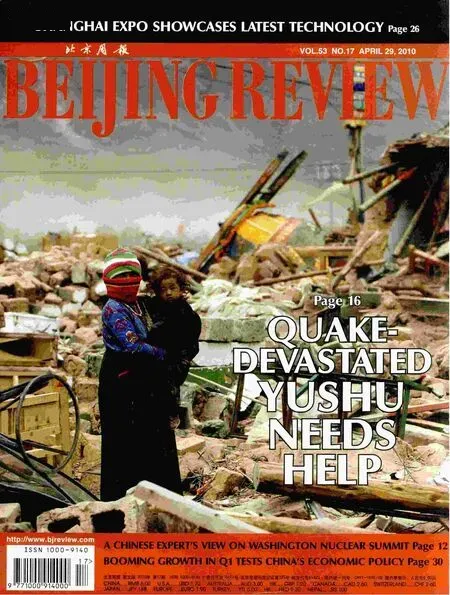

TRIO DEBATE: British Prime Minister and leader of the Labor Party Gordon Brown,leader of the Conservative Party David Cameron and leader of the Liberal Democrat Party Nick Clegg are seen participaing in a live television debate in Manchester on April 15

The only way the UK can do anything about this is to work within the EU to make its economic and political importance clear,and show tangible areas where this is the case, to the Unite States. Once again, this means Cameron will have to decide either to work more within the EU, with all the problems that pose for his party, or avoid this.

With China, the Conservatives will inherit a relationship that is in good shape.There are more trade, political and cultural links now than ever before. The London Olympics in 2012 give an immediate link between the two countries, with the UK being the successor as hosts to China.Cameron will also look hard at the fact that the UK, in 2009, was the main destination for Chinese investments into Europe. He will likewise think about other investment areas where money from China might be able to work for companies, job creation and industry in the UK, deepening the links in this area between the two countries.

On climate change, Cameron was an early enthusiast for more robust measures to cut down on carbon greenhouse emissions.The recession slightly impeded this, and now,like with many other countries, economic development has come fi rst, with less talk of trying to create a green economy in the next few years.

Public confidence in scientific claims about the impact of carbon emissions, at the same time, has declined in the last year.Even so, Cameron is likely to want to continue cooperating with China on combating climate change and continue the work started by the Labor Party. He will want continuity in the relationship rather than shifting to set out some bold new framework.

Domestic issues

Cameron has promised that, once he takes power, he will authorize a comprehensive review of defense expenditures for the UK. He has also promised that current levels of funding for both the National Health Service and the overseas development budget will be maintained.

But for the military, there are going to be tough choices, some of them over new military technology, and others about the UK’s nuclear capacity. There has been talk of an almost 16 percent in spending cuts. This would never have been achieved before—even under Margaret Thatcher who, in the 1980s, was famously keen on slashing public expenditures.

Rather, it is hard to see how any government is going to be able to achieve these sorts of cuts. Cameron has claimed that he can deliver 12 billion pounds ($18 billion) in cuts to the complete UK government annual budget of about 730 billion pounds ($1 trillion)by “ef fi ciency” savings. But that will almost certainly lead to job losses, something that has been avoidable so far.

With unemployment less than expected,he will likewise face a great deal of opposition should it increase as the economy gets better. He will therefore be faced with a classic dilemma—high debt and lower unemployment, or low debt and higher unemployment. With memories for many in the UK of a recession distant, the fallout from this might be very bitter indeed.

But trade with China is largely seen positively in the UK, and has attracted far less political fl ack than in the United States. There is no argument about, for instance, the rate of the Chinese yuan, and calls for re-evaluation.Nor are there claims that Chinese imports have led to rising levels of unemployment, as there have been in the United States.

It is thus very unlikely that China’s huge trade surplus with the UK and the EU will fi gure at all in the campaign, or in the thinking of the political parties as they move toward election day. That doesn’t mean that anger over job losses in the coming months might not seek to fi nd a scapegoat in China.

In that case, Cameron and his economic policy advisors will need to have a clear message on whether or not they believe this,and what they intend to do about it. They will need to decide on supporting, or opposing, protectionist measures through the EU.Instinctively, Conservatives are opposed to any protectionism, and are free traders.But public anger over job losses might inf l uence this, especially if the United States introduces more tariffs and grows more aggressive.

Finally, Cameron will have to make some fundamental decisions on the very political system by which he may be elected. There has been rising anger in the UK about the behavior of the members of parliament (MPs),with some of them prosecuted for corruption over their expense claims.

To date, UK politicians and politics have never before been held in such low esteem. It is very possible that this election will see a large proportion of people not voting, alienated and frustrated by the whole system. The continuing existence of an unelected second chamber (the House of Lords), of too many MPs (almost 700, for a population of 65 million people, compared with one Senator representing some 3 million people in the United States), of a crude“ fi rst-past-the-post” system that is unre fl ective of the complexities of public opinion,and of political parties linked to old social and class structures that have little purchase on modern society is only some of the issues.

For many in the UK, it is hard to see how as a country we are able to face our responsibilities and challenges in the world when we have put on hold some fundamental decisions at home. So, despite being from an aristocratic background and attending Eton, the UK’s most elite private school, Cameron might amaze everyone by being a genuine reformer in this critical area.

We shall just have to wait and see.

(The viewpoints in this article do not necessarily represent those ofBeijing Review)

The author is a senior research fellow at the Royal Institute of International Affairs in Britain