Searching for a younger Generation of Tibetan Minstrels toSing the King Gesar

2008-09-25

As time goes by, the development of epic performance culture naturally follows that the old blind minstrels who once specialized in singing the oral epic King Gesar (which they had memorized by their memories) are gradually dying out. Therefore, sooner or later, live performance of the oral epic King Gesar seems doomed to disappear. But does the successive loss of elite minstrels, such as the departure of Zhaba, Tsewang Jigme, Atak, Khetsa Zhaba, Wangchen Dorje, and Drolma Lhama, necessarily mean that the oral singing tradition of the King Gesar epic is going to perish where once it flourished?

Having heard of the discovery of new minstrels, I decided that it was of the utmost significance to investigate the folkloric minstrels. That is, while chasing after the old generation of minstrels, it was equally important to survey the nascent newcomers. Therefore, from 2006 onward, I made three field trips to the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) and Qinghai Province to interview a total of 21 of the younger generation of Tibetan minstrels.

Studies show that this younger generation mostly hails from remote nomadic areas. For example, in Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Qinghai, the elite minstrels live at the source of three famous rivers (The Yangtse River, the Yellow River and the Langcang River). Zhiduo County in Yushu lies on the bank of Drichu River -- the head of the Yangtse River, while Tador County is situated on the bank of Zachu River -- the headwater of Langcang River. The minstrels of Gulodro in Qinghai Province often spring from Matod, Gendun, Jigzhi and Padma, which is the source of the Yellow River and is located in a remote area far from the city of Xining. Sidar Dorje is from the very isolated Palbar County of Chamdo, TAR, which is the hometown of the veteran minstrel Zhaba. Most of those minstrels in Nagqu of TAR are from remote nomadic areas, including Shantsa County, Palgon County, Driru County and Amdo County. Their singing ability is clearly inherited from their ancient traditional culture but it also promotes creative development, as reflected by contemporary trends in Tibetan folkloric culture and the ongoing unique tradition of singing the heroic epic King Gesar.

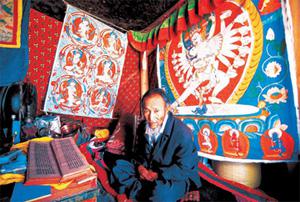

The ever-lasting divine enlightenment-Dawa Zhaba

Many minstrels credit the gods for their performance of the King Gesar since they all acquired their gift only after following their childhood dreams. They describe how their dreams always included the main themes of the King Gesar, such as an encountering with King Gesar, seeing men on horses and being asked to select materials from and reading or “devouring” the text of the King Gesar.

The story of Dawa Zhaba (aged 29 in 2007) is typical. He was born in Moyun Town of Tador County in Yushu. He had a dream when he was 13 in which an old clergyman asked him to choose one of three presents: the language of birds flying in the sky, the language of an animal walking on the earth, or speaking and singing the stories of the King Gesar. Considering the language of birds and animals would not bring about a wide understanding of human beings, he finally became convinced to choose the King Gesar. He has been reciting and singing it ever since.

Again, at 16, he dreamed of a whiteclad rider, named Lodro, an incarnation of Natsang Aden from Lungjie, who took him to visit King Gesar. Dawa Zhaba dreamed he paid homage to King Gesar when he was guided into a giant tent. He thought he could give tributes to King Gesar, but he had not brought anything with him. Therefore he decided to devote all his good works to King Gesar. He described enormous tents, replete with blossoming flowers and armed warriors, on a plantation. And then, Dawa Zhaba was crowned by the deputy of King Gesar as the incarnation of Natsang Aden.

On returning home, Dawa Zhaba was afflicted by a three-day illness. After recovering, he started to like the outdoors-the wild grassland and mountain slopes. Henceforth, the visions of landscape, mountains, and spectacular natural scenery haunted him and naturally caused him burst out in tears. Accordingly, he started to speak out one after another of the story of “The Heaven”, “The Birth of the Hero” and “The War between Hor and Ling”. From 13 to 17 years old, he crossed the mountains and grasslands to sing and recite the stories filling his mind. But he did this secretly because he preferred not to be noticed by others. Only after orally releasing all the stories in his mind, did he feel mental and physical relief.

In his 17th years old, he went on a pilgrimage to Lhasa via Nagqu. He encountered a minstrel. On hearing the singing of the first part of “The War between Hor and Ling” after this minstrel, he innately came up with the second part of this story. Afterward, they both sang and recited together. He found he could instinctively sing “The Conquest of Minu and Looting of Its Silk and Damasks”. After five hours he had finished singing, but the minstrel had disappeared. Next he came to Chukha. In his dreams he sang and recited stories continuously until sunset the next morning. He had inadvertently dripped saliva on his chest and wet his clothes. When he woke up, he found himself being observed curiously by the people outside. The story he sang was “The Conquest of Kachi and Looting of its Jades”. In this voyage, his cousin (also a minstrel from Sumza of Tador) and a friend accompanied him.

Soon, news of Dawa Zhabas singing feat with the King Gesar spread throughout the grassland. In 1996, the Communal Art Gallery of Yushu employed him. He claimed that he could sing a total of 170 volumes of the King Gesar. At present, only 19 volumes of his singing have been classified, three have been transcribed into written language, and a series of 12 tapes of “The Conquest of Tromunoi and Jades” were sold in markets. In 2006, these tapes were recorded by Jin Hua and then published by the China Association for Preservation and Development of Tibetan Culture. At present, Dawa Zhaba is living with his parents in Jyegu. He has made a contract with the government office to work on the preservation of the oral culture of the King Gesar on a fixed salary of 1700 Yuan per month . While adopting a modern lifestyle, driving a car and wearing with a gold watch on his wrist, his stories of the King Gesar constantly flow from his mind.

In 2003, in order to celebrate the millionth anniversary of the King Gesar, he was invited to participate in the 5th international academic seminar on the oral epic and presented his singing of it to scholars from both home and abroad. His performance gained unanimous approval. In 2005, I interviewed him when he came to Beijing.

Dawa Zhaba never studied in school but he held his stories in his memory. He is usually totally engrossed when he sings and is rarely interrupted. He also always talks very fast. Because of that, one tape could record more history than recordings of the singing of old minstrels. It seems as though the gods truly bestowed the stories in his memory. But then, he never denies that he has listened to the singing and stories of his uncle - also a King Gesar minstrel. Speaking of his singing of “The War between Hor and Ling”, he said his version is shorter than his unclessinging. He says there were three versions of this story that were either long or medium or short. Only by asking the gods before the minstrel performs could he determine which version was requested at a special circumstance or occasion. Singing of the long version of the story of “The War between Zhugu and Ling” often needs 200 tapes to accomplish. For the long version of “The War between Hor and Ling” and “The Conquest of Mongolia and the Seizing of its Horses” usually fit on 250 tapes, but the short version only fills three to four tapes while the medium one requires 50 tapes. However, the short version is unlikely to be delivered by minstrels by virtue of the potential for harm to befall the singers (because of the supposed lack of reverence toward King Gesar). Sumza is one year younger than his cousin Dawa Zhaba. He is outstanding amongst minstrels in Tador. But Dawa Zhaba has never fallen behind him and he exhibits a unique flexibility when he sings.

Sidar Porje-the Little Minstrel from Old Zhaba

Living in the Tibetan cultural and geographic environment, the younger Tibetan minstrels are profoundlyinfluenced by their older generation and are confined within the traditional rites of the King Gesar, perfectlymaintaining the tradition of singing the story of the King Gesar in terms of their performance, the contents, and even the way of their receiving messages from the gods. They are absolute epitomes of the old tradition of King Gesar singing.

Sidar Dorje, the youngest minstrel in Palbar, is a good example of one successfully inheriting the traditional culture of singing. He was born and grew up in the hometown of Zhaba, the famous minstrel. When discov-ered by outsiders, he was actually referred to as “artistic minstrel Zhaba”, even though he never saw old Zhaba. His singing, however, is identical to that of old Zhaba. Before kicking off, in his mind, he always visualizes a clear panorama of the scene in the story. In contrast to those old minstrels (such as Zhaba and Samdrup who hardly even paused after they started to sing because they perceived that singing of the King Gesar is a process of consecration and any halt before finishing each part will offend King Gesar, and then this singer will be punished by King Gesar), Sidar Dorje is so flexible while singing that he could stop anytime he felt appropriate.

Featuring with a unique pronunciation of words when he was singing, Sidar Dorje often enriches his text with flowery words and phrases, even including a little bit of Satengdialect. However, most of his singing is perfect literary language. In addition, he is fond of cutting each war story into two parts: the battle as the first part and victory as the second, including carving up the booty. In total, there are eleven stories, such as “The War between Hor and Ling”, “The War between Jiang and Ling”, “The War between Moin and Ling”, “The Conquest of Dashi and Seizing of its Horses”, “The Conquest of Azha and Seizing of its Agates”, “The Conquest of Tsawa and Seizing of its Arrows”, “The War between Hinterland and Ling”, “The Conquest of Mugu and Seizing of its Mules”, “The Conquest of Kachi and Seizing its Turquoises”, “The Conquest of Minu and Seizing of its Silk and Damasks”, and “The Conquest of Zhugu and Seizing of its Engineries”. Apart from these, Sidar Dorjes particular specialty is his exclusive stories, including “The War between Nang and Ling” and “The King of Sibugta”. He argues that people living in different geographic areas like different parts of the same story. Forinstance, people from Nagqu are fond of the first part of “The War between Hor and Ling”, while the preference of people from Chamdo is actually the second part of the story. The background behind this is that in the first part, Hor invaded Ling and killed Gyaltsa and the son of Chaotong, and then raped Drumo. Khampa people believe it was a portent but people from Nagqu, where Hor is located, would not like to be humiliated because the second part of the story describes how Ling defeats Hor.

Interestingly, the same miracle occurred with both Sidar Dorje and Zhaba (When he was 11 years old), they shared a similar dream that led them to start to sing the King Gesar. Sidar Dorje said: “I recall that happened when I was studying in the Primary School in Sateng Town. One night I finished my study, returned to my dormitory and felt into sleep. I dreamed I was wandering in a place of mountains, rivers, flowers, grassland and flocks. I saw two tall men dressed in armor riding toward me. I felt I was very small in comparison with them and was afraid. However, they approached me quietly, dismounted from their horses and introduced themselves as Shingpa and Danma.Shingpa presented a Karda to me politely and said: ‘King Gesar told me to bring a man to him. It is you. Thereupon, I was guided to a huge white tent, surrounded by other enormous tents, which was crowded with people. Shingpa reported to King Gesar who was sitting inside the white tent: ‘Here is the man who your Holiness asked for. King Gesar observed: ‘Today is an auspicious day. On seeing many books inside the tent, I was ordered by King Gesar to eat one of these books. While I was intimated and won-dered how I could eat this book, Danma came to me and pushed the book into my mouth. Then King Gesar said: ‘You must visit the Heaven because it is an auspicious day. Then he turned around and suddenly a spectacular rainbow appeared in front of me. When one of my feet touched the rainbow, he disappeared. After I woke up, I was semi-conscious until I finally realized I was still in my dormitory, but the images of the horse riders and the words of the book constantly haunted my mind. I walked out of the dormitory and sat down on a ping-pong table. My mind cannot help returning to such a fascinating and miraculous dream... and every part of the dream penetrated to the depth of my mind. I felt I had butterflies and it seemed too much for me.”

Here is Sidar Dorjes story:

I felt so full and did not want to eat anything for breakfast even through I saw my classmates were enjoying the food. In the first morning class, I was utterly absentminded. The images from the dream constantly bothered me. My heart was beating fast but I could not speak. My classmates realized something had happened to me. When the second class started, which it was music class, I was overwhelmed and could not control myself anymore. I said to one of my classmates: “I must speak out.” The music teacher Sonam Chotso heard and invited me to stand in front of the class to sing what I wanted to. So I sang everything in my mind, accompanied with mental visualizations of the landscape and textual information from the dream. On having heard what I sang, Sonam Chotso suddenly understood and commented: “You want to sing the ‘Gesar”. I was confused by his words and queried: “What is the ‘Gesar?” On understanding what the teacher then explained to me, I bore endless reverence toward the King Gesar. Henceforth, I always sang wherever and whenever my mind dictated.

Sidar Dorje said he had never heard anyone sing the King Gesar. Nevertheless, in his hometown Ralpa Village, an old man often told stories with nasal tobacco purveyed by the village kids as an incentive. His stories included the stories about mice and rock rats and those of Aku Tenpa. Sidar Dorje said he was greatly impressed by him.

What really happened to Sidar Dorje is still a mystery though he denies he has ever, to any extent, been taught the King Gesar. At any rate, the King Gesar is widespread in Palbar County where Sida Dorje lives. The folkloric cultural milieu was around him since he was a child. And his personal preference for traditional culture more or less shapes his ability and skill in singing the King Gesar.

In October 2006, when I interviewed Sidar Dorje he was studying in Grade Three at Palbar Middle School. In 2007, he successfully passed the exams and gained admission to high school.

A Big Gathering of Young Minstrels in the Gesar Concert

In the old days before 1950s, the minstrels embarking on singing the King Gesar were looked down upon by society. Indeed they lived a nomadic lifestyle throughout the plateau by following the pilgrims and trade caravans to provide entertainment. Nevertheless, with endless trekking and living in harsh environments, the minstrels achieved inconceivable feats of singing the King Gesar.

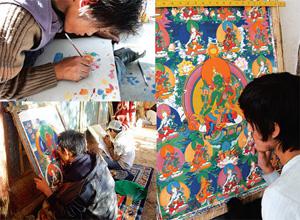

By contrast, the younger minstrels are receiving a stable income from animal husbandry. But they drift to urban areas in their preference for modern living and convenient transportation, where their singing of the King Gesar always enhances their reputation. For example, they are fond of staying in the downtown of Nagqu. In the 1980s, the Communal Artistic Gallery of the Cultural Bureau of Nagqu Prefecture established a King Gesar concert (named Sgrung Khang) by providing a platform for singing the King Gesar to the public. The cost of each concert was only one to two Yuan, but people could spend half a day to listen the singing. Soon the successful concerts in Nagqu led to the gradual commercialization of the Gesar cultural activities. Three individual businessmen founded several similar concerts. They employed qualified minstrels from the community by offering them a salary ranging from 300 to 800 Yuan to sing the King Gesar. Gradually, the increasing demand for minstrels attracted those young artists to settle down in the downtown of Nagqu with stable incomes.

Nowadays over a dozen young minstrels, throughout the last ten years,

have settled in the downtown of Nagqu including Ngawang Palden from Palgon County, Rigzu from Driru County, Namse from Amdo, and Made, Tashi Dorje, Dorje Rampa, Luozang, Chusang, and Phrub from Nagqu County. For the most part, they are all performing in the Gesar Concerts in the downtown area, but several of them also like to work for other businesses, along with their singing of the King Gesar. Tashi Dorje is an example of this. While singing in the concerts, he is also acting as a traditional healer to serve the community. Having earned enough money for his family, he is building his house in the downtown and preparing to permanently settle there. In fact, the pioneer minstrel in the downtown was Tsering Dradul who came in 1987 from Shantsa. Now he has joined the formal staff of the Nagqu Art Gallery and is in charge of gallery business. Palgya is another successful successful minstrel to settle down and he is also working as a staff member in the Gallery.

These minstrels have flourished from their experience of performing in concerts, accompanied with unique opportunities to exchange skills amongst themselves. At present, the downtown of Nagqu has been acknowledged as an authentic nexus to disseminate and exchange the culture of the King Gesar, due to the establishment of the Gesar Concert which acts as the leading force to attract more and more folkloric minstrels to work together to revive the ancestral culture.

Since the 1980s, China has launched a sizeable restoration and preservation of the King Gesar culture in concert, along with raising the social status of the minstrels in acknowledgment of the public value of Gesar culture. As a result, an exclusive and exceptional ethos in which the Gesar culture is functioning as the core of Tibetan spiritual life has been formed in Tibetan inhabited areas. Under this ethos, a school of younger minstrels of the King Gesar is forming. They are celebrated in multiple media (such as broadcast, newspapers, and books) as well as Tibetan opera and amenities to express the essence and feats of traditional culture. All of these contribute greatly to the scope for younger generations to create an extensive and intensive atmosphere for the revival of Gesar culture.

The King Gesar oral culture is making progress in revival and development. We must keep on this courseand maintainits sustainability by paying special attention on it. This is one of the approaches to effectively preserve ethnic Tibetan culture. We should never give up.