The First Step Toward Super-Ministries

2008-06-25staffreporterLIUQIONG

staff reporter LIU QIONG

WHEN China unveiled its plan for government restructuring in mid-March, it turned out that the number of ministries and commissions under the State Council would be reduced from 28 to 27, instead of to 21 as had been widely expected. “The reform is more modest than people had anticipated,” said Prof. Mao Shoulong, dean of the Public Administration School, Renmin University. Nevertheless, he said, it is the first serious effort to streamline the government by reducing the number of ministries, commissions and departments since the onset of Chinas reform policies nearly 30 years ago.

The Sixth Institutional

Reform of the Central Government

Overlapping functions are a chronic headache for Chinas government departments. Research has shown, for example, that the process of growing and consuming a cabbage may involve as many as 14 ministries, commissions and bureaus. To name just a few: the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Water Resources, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, the Ministry of Health, the General Administration for Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine and the State Food and Drug Administration.

According to statistics, duplication was found in more than 80 functions of State Council departments. The Ministry of Construction, for instance, shares parts of its vast domain with 24 other ministries and commissions.

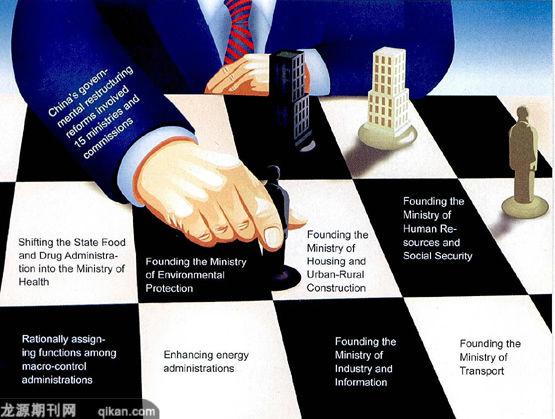

On March 15, the first session of the 11th National Peoples Congress, Chinas highest legislature, approved the State Council Reform Schedule, according to which 15 state organs will be regrouped and the number of ministry-level administrations cut by four.

Most prominent among these is the establishment of an energy bureau under the National Development and Reform Commission; the incorporation of some functions of the Commission of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense with those of the Ministry of Information Industry; the creation of the Ministry of Industry and Information; the expansion of the Ministry of Communications into the Ministry of Transport, to take over the Civil Aviation Administration and the Ministry of Constructions section for urban passenger transport; the merger of the Ministry of Personnel and the Ministry of Labor and Social Security to become the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security; the upgrade of the State Administration of Environmental Protection into the Ministry of Environmental Protection; the restructuring of the Ministry of Construction into the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction; and the incorporation of the State Food and Drug Administration into the Ministry of Health.

This is the sixth reform of Chinas administrative structure since 1982. The previous five largely succeeded in weaning the government away from the habits of a planned economy, but efforts to streamline it yielded few results. Instead, the government actually grew larger following each reform, which is why the notion of creating super-ministries has met with such skepticism.

Wang Yukai, a professor at the National School of Administration, dismisses such doubts: “In contrast with the previous five reforms, the super-ministry plan is not meant to merely trim the government. The ultimate purpose is to establish a power structure where the three parties of decision-makers, enforcers and supervisors coordinate with one another and provide mutual restraint.” Wang is among the first scholars to advocate super-ministries.

Prof. Mao Shoulong, who submitted a report to the State Council on super-ministry reform not long ago, shares those views. As he explained: “The government reshuffles during the 1980s focused on trimming the number and size of state organs. The ones in the 1990s were aimed at laying a foundation for the market economy. And in 2003, the government defined its roles on issues such as macro-economic control. The current reform, however, goes beyond economic functions to include the market, society and public services as well. The core task is to establish a service-oriented government.”

Soaring Administrative Costs

Prof. Mao sees substantial benefits in the proposals for a super-ministry system. He likens it to a small class where every student has a chance to speak, which leads to better exchanges. As a result, the class can achieve better results. He believes the appropriate number of decision-making bodies should be 15 to 18, and that each one should take responsibility for different issues so as not to interfere with the others.

This pattern can also hold down Chinas administrative costs. “Under the super-ministry system, administrative costs will be pared with the cut in the number of government departments. What is more, an additional sum will be saved thanks to greater inter-departmental coordination,” he said.

Statistics have shown that Chinas administrative outlay soared 87-fold in the 25 years between 1978 and 2003, jumping from 4.71 percent to 19.03 percent of the national ravenue. Meanwhile, post-related expenditures by public servants swelled by more than 140 times, leaping from 4 percent of national revenue in 1978 to 24 percent in 2005.

The inefficient roles administrative organs play and the overlapping of their functions have been putting a growing drag on Chinas social and economic development. According to a recent study by Fan Gang, secretary general of the China Reform Foundation, the contribution of administrative costs to Chinas economic growth was rated at minus 1.73 percent between 1999 to 2005.

In Prof. Maos opinion, smaller ministries are more likely to set up more posts. As several institutions may be involved in the handling of one issue, there comes the need to establish coordinating sections at all levels. The problem was laid bare once more during the snow disaster that hit southern China earlier this year, Mao said. As the result of an unclear division of duties between the central and local governments, as well as theduplication of department functions, the efficiency of the disaster response and relief effort was impaired, and the cost was high.

Toward a Service-oriented Government

Officials also appreciate the idea of a neatly structured government. “Fewer departments will enable easier coordination among them. Consequently, the government will be more efficient, and will play a more constructive role in the macro-economic management of the market economy, as well as in public services,” said Pan Yonghe, chief of the Communications Department of Jiangsu Province.

Pan spoke from personal experience. When a passenger travels from Beijing to a town in Jiangsu, he or she has to first take a train, then switch to a long-haul coach. But railway stations and bus stations are often far apart, because they were designed and run by different administrations.

“Formerly, departments only worked on their individual plans, and never thought about the broader perspective. The intent of establishing an integrated communications administration is to make travel more convenient for people.” Between 2005 and 2007, Pans department incorporated with the provincial Port Bureau, the Aviation Industry Development Office and the Railway Office, and eventually took control over all transport sectors, including highway, aviation, railway and water transport.

“The government regrouping is not merely to shed some ministries or commissions. The ultimate goal is to transform the governments role and elevate its performance in terms of public services,” said Gao Xiaoping, vice-president of the China Administration Society. “The core of building a service-oriented government is to enhance the governments public service role. That is why public service sections, including health, human resources and communications, are at the top of the current institutional reform agenda.”

The move to upgrade the State Administration of Environmental Protection into a full-fledged ministry aims to intensify the efforts in macroscopic guidance, overall coordination and supervision. The merger of the Ministry of Personnel and the Ministry of Labor and Social Security aims to demolish the systemic discrimination against employees of corporations, institutions and the government, and the creation of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction demonstrates the importance the government attaches to the housing issue. It aims to exploit state resources to provide homes to medium- and low-income families. At the same time, the takeover of the State Food and Drug Administration by the Ministry of Health is expected to provide a positive impetus toward better management of food and drug safety.

In responding to complaints about the extent of the reform, Yuan Shuhong, vice-president of China National School of Administration, said: “A discreet and gradual process is necessary.” He argued that it took a long time for the number of ministries in developed nations to drop below 20, while those in developing nations mostly remained above 20, sometimes even numbering 40 to 50 in some countries. “Caution against haste and detours is crucial for the success of the reform,” the official-turned-scholar warned.

Previous Five Government

Restructuring Initiatives Since 1982

The first (1982): State Council organs shrank from 100 to 61, and their staffs from 51,000 to 30,000.

The second (1988): State Council organs were reduced from 45 to 41, and more than 9,700 jobs were shed.

The third (1993): State Council organs and the organizations immediately under them were reduced from 86 to 59, and their staffs were trimmed by 20 percent.

The fourth (1998): Fifteen ministries and commissions were canceled, four were established, and three were renamed. State Council organs (its General Office excluded) dropped from 40 to 29.

The fifth (2003): New organs of the State Council were added, including the Ministry of Commerce, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, the Banking Regulatory Commission, the State Food and Drug Administration and the State Administration of Work Safety. The National Development Planning Commission was remolded into the National Development and Reform Commission. The State Council ended up with 28 organs.

The Sixth Institutional Reform

of the Central Government

Newly established ministries: the Ministry of Industry and Information, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction.

Abolished ministries and commissions: the Commission of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, the Ministry of Information Industry, the Ministry of Communications, the Ministry of Personnel, the Ministry of Labor and Social Security and the Ministry of Construction.

Existing organs of the central government: the Ministry of Industry and Information, the Ministry of Transport, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Land and Resources, the Ministry of Railways, the Ministry of Water Resources, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Health, the National Population and Family Planning Commission, the Peoples Bank of China, the National Audit Office, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, the General Administration of Customs, the State Administration of Taxation, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce, and the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine.

The current reform goes

beyond economic functions to

include the market, society and public services as well.