The Making of the“Tibet Issue”

2008-06-25CHENQINGYING

CHEN QINGYING

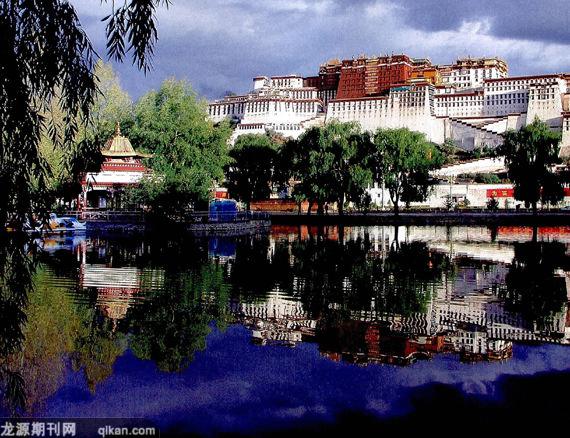

TIBET has been an integral part of China since the 13th century, when the Mongols unified the country and established the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). The central government placed the Tibetan region under its direct jurisdiction and set up three Offices of the Pacification Commission and the Chief Military Command to exercise control over Tibetan-inhabited regions. Of those, the one in charge of U-Tsang and Ngari had jurisdiction over todays Tibet Autonomous Region, except for Qamdo. Since then, Tibet has remained an administrative jurisdiction of China through the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, the Republic period (1912-1949) and the Peoples Republic (since 1949).

However, that historical fact was distorted in the 19th century, when Western imperialists embarked on a campaign of expansion and hegemony in Asia, and, to serve their hegemonic purposes in East Asia, concocted the “Tibet Issue” with a view to separating Tibet from China. The “Issue” has remained an issue ever since, as anti-China forces in the Western world repeatedly utilize it and its spokesperson, the Dalai Lama, whom they have funded and recruited into their service. The Dalai Lama and his separatist forces have taken every possible opportunity to create “Tibet Issue” incidents, the latest being the March 14 Lhasa riots.

The century-long “Tibet Issue” can be divided into two historical periods, with the founding of the Peoples Republic in 1949 as the demarcation: the period of agitation by British imperialists, and the period of meddling by anti-China forces in the United States, led by the CIA under cover of the Cold War.

After Britain colonized India, it continued its expansion into the Himalayas. Between 1814 and 1864, it invaded and seized control of Afghanistan and Persia, and the British Army launched a northward invasion from India, turning Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan into British Indias protectorates. Its next target was Tibet, but its ambitious expansion alarmed Chinas central government and led to conflicts with Tsarist Russia, which was also expanding in Central Asia.

In 1888, the British Army launched its first invasion of Tibet on the pretext of border disputes and trading rights, forcing an intimidated Qing government to sign the Sino-British Tibet-India Treaty, and later its supplements. The unequal treaty and its addendums granted Britain preferential trading rights in some Tibetan areas, including Yadong and Gyangze.

Between 1903 and 1904, Britain launched a second invasion of Tibet, only to meet with heroic resistance by local Tibetans in Pagri and Gyangze. After the British Army forced its way into Lhasa, the British government coerced the local Tibetan government into signing the Lhasa Treaty, which was strongly opposed by the Qing government and denounced by Tsarist Russia. The British Army soon withdrew from Lhasa for lack of supplies and the frigid weather.

After the two military attempts failed to achieve their goal of turning Tibet into a colony, Britain changed its strategy, taking advantage of the Qing governments diplomatic and domestic troubles, which left it no time for Tibet, to broaden its contacts with the Tibetan upper class, provoking the discontent and resentment of some slave owners, sabotaging their relations with the Qing government and spreading the idea of “Tibet Independence.” It tried to wrest Tibet away from China by encouraging and supporting Tibetan separatists, so that Tibet could serve as a buffer between China, India and the Russian sphere of influence, and to help protect British colonial rule in India.

Before the British invaders entered Lhasa in 1904, the 13th Dalai Lama left for Mongolia. When he returned to Lhasa in 1909, he clashed with Qing officials there before leaving again, this time for British India, thereby providing further opportunities for Britains separatist conspiracies.

Around the 1911 Revolution and the founding of the Republic, China was in political turmoil, and Britain stepped up its separatist agitation in Tibet. The British government and its India Office proposed in a 1912 memorandum on the situation of Indias neighbors that China could retain its nominal “suzerainty” over Tibet, while Tibet should rely absolutely on India and keep the Chinese and Russians at bay. The memo also stated that Tibetan areas in Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai and Yunnan should be included in a “Greater Tibet.” Based on the memo, John N. Jordan, British minister to China, made a five-point separatist statement in 1912. He forced Chinese President Yuan Shikai to send a delegation to the 1913-1914 meeting between the central government of China, Britain and Tibet in Simla, in northern India, by threatening to withhold recognition of his legitimacy.

In Simla, British representative Henry McMahon conspired with Tibetan representative Shagra Paljor Dorje against Chinese representative Chen Yifan (Evan Chen). The British side proposed that Tibet and the Tibetan areas in the four neighboring provinces be divided into an “Outer” and an “Inner” Tibet, that the “Inner Tibet” be administered by China for the time being, and that the “Outer Tibet” practice autonomy, with which China could not interfere. By doing so, Britain planned to control “Outer Tibet” first, and then “Inner Tibet,” when the time was ripe. After the Simla meeting ended without agreement, Britain redoubled its support for the Anglophiles among the Tibetan upper class, and goaded the Tibetan army into attacking Sichuan and Qinghai.

In 1933, the 13th Dalai Lama died. The central government conferred on him a posthumous title, and sent its special envoy Huang Musong to Tibet for the title-granting and condolenceceremonies. In the winter of 1939, a five-year-old boy named Lhamo Toinzhug, from Qinghai, was escorted to Lhasa and established as the 14th Dalai Lama. The enthronement ceremony was presided over by Wu Zhongxin, dispatched by the central government of the Republic.

During World War II, when Britain and China were allies, Britain nevertheless tried to prohibit and sabotage Chinas sovereignty over Tibet. On August 5, 1943, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden sent a memo to Chinese Foreign Minister Tse-ven Soong describing Tibet as “an autonomous State under the suzerainty of China” that “enjoyed de facto independence.” He called again for another Simla meeting, which the Chinese government ignored. Britains “Tibet Independence” conspiracy finally collapsed when India announced independence in 1947.

The world entered the Cold War era after World War II. The United States overtook the United Kingdom as the leader of the Western world, and as the leading patron of “Tibet independence” as well. Indeed, the CIA had included Tibet in its strategic calculations since its establishment in 1947. During the war, under the pretext of inspecting road construction for the transport of war materiel in Tibet, American President Franklin D. Roosevelt dispatched his envoys to the Dalai Lama, sending gifts and the message that he hoped Tibet could maintain its status quo as a small independent nation. In 1950, the year the Korean War broke out, the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) entered Tibet and soon liberated Qamdo. Weighing the situation, the Dalai Lama sent a delegation, headed by Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, to Beijing. Following negotiations, it signed the 17-Article Agreement with the Central Government on May 23, 1951, and the peaceful liberation of Tibet was realized.

But attempts by the CIA to disrupt peace and stability in the region never ceased. The CIA approached two elder brothers of the 14th Dalai Lama – Gyalo Thondup and Thupten Jigme Norbu – conspiring with them to establish anti-government guerillas in Tibet. The CIA offered training to Tibetan militias, first in Taiwan, then on Saipan Island, and lastly in Colorado, in the U.S.At Camp Hale, in Colorado, alone it trained more than 300 Tibetan spies, and in August 1957, the U.S Air Force dropped two Tibetan guerillas in Sangri County, in southern Tibet. They established contact with Lhasa rebel leader Anzhugcang Goinbo Zhaxi early the following year, and reported everything to the CIA. On April 20, 1958, approximately 5,000 rebel leaders and representatives of the three major monasteries – Drepung, Sera and Ganden – held a secret meeting at which they agreed to set up a guerrilla base in Shannan. On June 24, the “Religion Guards of the Four Rivers and Six Ranges” was founded, with Anzhugcang Goinbo Zhaxi as commander. In September, it received the first U.S. air drop of food and ammunition.

On the morning of March 10, 1959, rumors spread across Lhasa that the PLA was going to arrest the Dalai Lama and his officials. Thousands of Tibetans were manipulated into gathering around Norbu Linka, the Dalai Lamas residence, to prevent him from going to a song and dance performance hosted by the PLA to which he was invited. Meanwhile, demonstrations were organized under the slogans of “Tibet Independence” and “No Han People.” More than 2,000 rioters seized the Jokhang Monastery, and a “Tibet Independence” conference was held in Potala Palace in the afternoon.

On the morning of March 17, the 24-year-old 14th Dalai Lama fled his palace in disguise, and headed toward Shannan with the help of CIA agent Tony Poe. The CIA air-dropped food supplies to him along the way, and kept records of the entire trip. The Dalai Lama and his cortege kept in radio contact with CIA stations en route.

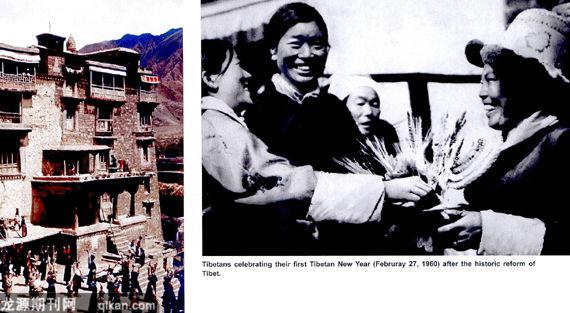

As soon as the Dalai Lama left Lhasa, rebels launched full-scale attacks on PLA garrisons and government departments in the city, killing and looting. The revolt was put down in two days.

After the riot in Lhasa was foiled, the CIA regrouped 2,100 of the rebels to set up a guerilla base in Mustang, Nepal, where it provided them with ammunition and training. They were later sent back to Tibet to collect intelligence and engage in sabotage.

Between May and June of 1959, the Dalai Lama set up his “government in exile.” He later convened the “Peoples Congress of Tibet,” and promulgated the so-called “Constitution,” which stipulates that “the Dalai Lama is the head of state,” “the ministers shall be appointed by the Dalai Lama,” and “no work of the government shall be approved without the consent of the Dalai Lama.”

Despite the fact that no country in the world recognized the Dalai Lamas “government in exile,” the United States instructed several countries to raise the issue of Tibet at the United Nations General Assembly in 1959, 1960, 1961 and 1965. Resolutions on Tibet were passed in 1961 and 1965.

Declassified U.S. documents reveal that for much of the 1960s, the CIA controlled a Tibet fund of US $1.7 million annually, of which US $500,000 went to the 2,100 guerillas in Nepal, and US $180,000 was a personal subsidy for the Dalai Lama. The fund was cut to US $1.2 million after the training camp in Colorado was shut down in 1968,and was discontinued after diplomatic ties were established between the Peoples Republic of China and the United States in 1979.

The U.S curtailed its aid to the Dalai Lama during its contest with the Soviet Union in an effort to win over China during the Cold War, and the Dalai clique once lamented that they were “Cold War orphans.” But anti-China forces in the world have never given up their strategy of restraining China by using the “Tibet Issue” and the “Taiwan Issue,” nor have they halted their support for the Dalai clique.

Since the mid-1980s, the Dalai clique has stepped up its drumbeat for “Tibet independence” around the world, and has regularly infiltrated into Tibet to stir up trouble. It has sent delegations to the West using various names, selling their stories to the Western media, lobbying for an independent Tibet, and slandering China under the pretext of democracy and human rights. Between 1987 and 1989, the Dalai clique repeatedly incited riots in Lhasa, causing havoc to the local economy, society and ordinary peoples lives. Ironically, the Dalai Lama was awarded the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize. After that, the Dalai Lama visited more than 50 countries to promote separatist activities.

As history shows, at the root of the “Tibet Issue” are the foreign invasion and splitting of China. In the early years, British imperialists sowed dissension in the region, and cultivated Tibetan separatists. Following World War II, the U.S manipulated the “Tibet Issue” to check China and Communism as part of its global strategy. Today, foreign anti-China forces still play the Tibet card in a desperate effort to hold back and split China. And the Dalai clique willingly works as their pawn in the hope that their aid and support can help it realize the fantasy of “Tibet independence.” All of these factors have contributed to the longevity and complexity of the “Tibet Issue.”

CHEN QINGYING is a senior researcher for the China Tibetology Research Center.

History was distorted in the 19th century as Western imperialists embarked on a campaign of expansion and hegemony in Asia.

The CIA offered training to Tibetan militias,

first in Taiwan, then on Saipan Island, and lastly

in Colorado, in the U.S.

Declassified U.S. documents reveal that for much

of the 1960s, the CIA controlled a Tibet fund of

US $1. 7 million annually.