Prehistoric Jade Artifacts of China

2024-05-14

In this book, Mr. Mou Yongkang, a senior figure in Zhejiang archaeology, revisits the concept of the “Jade Age.” Centered on the theme of prehistoric jade artifacts, he explores their distribution areas, carving techniques, historical context of assembly, the emergence and combination of ceremonial jade sets, and their symbolic meanings, asserting that ancient jade is a crucial medium for exploring Eastern ideological forms.

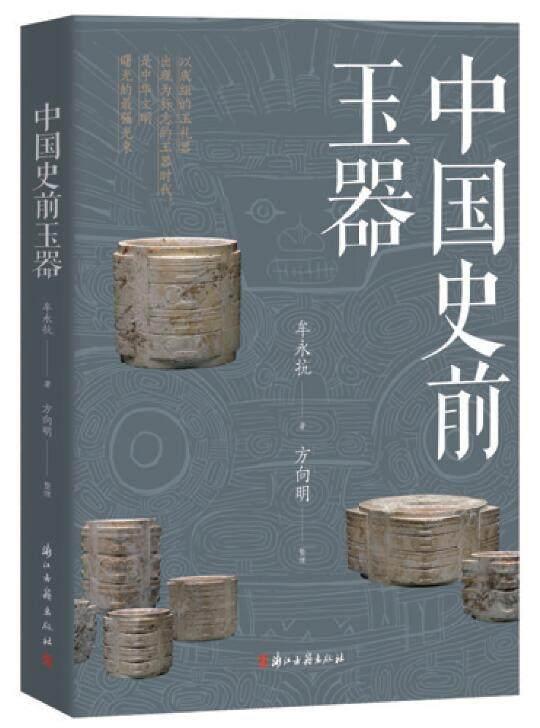

Prehistoric Jade Artifacts of China

Mou Yongkang, Fang Xiangming

Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House

January 2024

280.00 (CNY)

Mou Yongkang

Mou Yongkang is a renowned archaeologist and one of the founders of Zhejiangs archaeological endeavors. He has long been engaged in field archaeological surveys, excavations, and research. He has made significant contributions to the establishment of archaeological cultural types during the prehistoric period in Zhejiang Province, the study of prehistoric jade artifacts and the origins of Chinese civilization, as well as explorations in the archaeology of Zhejiangs porcelain kiln sites.

Fang Xiangming

Fang Xiangming, a graduate in archaeology from the Anthropology Department of Sun Yat-sen University, has been serving at the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. He is currently the director and a researcher there, holding positions as the vice president of the Zhejiang Archaeological Society and a member of the Zhejiang Cultural Relics Appraisal Committee.

The west coast of the vast Pacific is a magical land that has nurtured our Chinese nation. Around the time humans first appeared, the Himalayan orogeny was gradually shaping the region into what is known as the “Roof of the World.” At least before the end of the Last Glacial Period and the onset of the Holocene (15,000 years ago), the area east of the Himalayas and the Pamir Plateau had become a relatively independent geographical unit on the ancient landmasses of Asia and Africa. With global temperatures rising and glaciers retreating, some tribes that originally lived here pursued large ice-age animals, including reindeer, moving towards the far north, while other tribes started the Neolithic Age by cultivating grain crops in the lower river valleys or marshlands. To the north of this region, the Gobi Desert and the Greater and Lesser Khingan Ranges form a barrier, while its southern edge is bordered by the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and the Ailao Mountains, created by the transverse mountain range. The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, with rivers flowing eastward into the Pacific Ocean and southward into the Indian Ocean, forms the geographical features of a relatively independent geographical unit in East Asia. On this fan-shaped terrain sloping from northwest to southeast, the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, a pair of rivers sharing the same origin and destiny, run through from west to east. The presence of the Japanese archipelago blocks the warm currents of the Pacific Ocean, making the East Asian region between the worlds largest landmass and largest ocean the place with the hottest summers, coldest winters, and greatest temperature differences on Earth. Yet, this harsh climate brings the Pacific monsoon, creating a beneficial phenomenon of warm water coexistence that is highly favorable for the growth of grain crops. The existence of these relatively isolated geographical units enabled the cultivation of millet and rice from the Poaceae family here, alongside wheat originating from West Asia, North Africa, and Southern Europe, and maize from another geographical unit, the Americas, becoming one of the three major grain origins that modern humans rely on for survival.

The indigenous characteristics of the Neolithic cultures in East Asia are likely rooted in this environment. The advent of agriculture and the resultant settled life allowed farmers to work and live in various distinct regions, thus developing into the Neolithic ages, systems, and types. In the past, the characteristics we saw in the relationships between ages, systems, and types were often differences in material life, displaying a sequence of inheritance that was self-contained and had its sources. However, it cannot be excluded that before settling in these areas, due to living together in this relatively enclosed region, the possibility of forming some common ideological forms existed. The burial custom of sprinkling ochre powder on the deceased, discovered in the Zhoukoudian Upper Cave Site excavations of the 1930s, indicates that a certain level of primitive worship (belief) had already formed at that time.

Excavations in the 1970s at the Haicheng Xiaogushan site in Liaoning uncovered small clam decorations engraved with ray-like short lines. On these clean, white, round clam shells, the engraved short lines were dyed red, inevitably evoking the image of the sun. With the Xiaogushan cave deposits dating back about 40,000 years, it is likely that some form of sun worship-related concept existed among the Paleolithic populations (including their descendants who remained in Asia) before crossing the Bering Strait. After entering the civilized era, the self-designation of the Chinese empire as “China” embodied notions of centrality and superiority. It is clear that before entering civilized society on this relatively enclosed East Asian continent, alongside creating a distinctive material culture, there was also a gradual formation of ideological forms rooted in a unique way of thinking.

In modern gemology, jade includes two types of non-monocrystalline chain silicate minerals, pyroxene, and amphibole, along with the nephrite series. The former, a sodium aluminum silicate, commonly known as nephrite or hard jade, colloquially referred to as jadeite, appeared relatively late in China. The latter, an iron magnesium silicate known as soft jade or nephrite, was the traditional jade used in ancient China. It is a mineral aggregate with a microscopic fibrous structure. Due to the varying number of monocrystals forming each fiber, the thickness of each fiber varies significantly. Some can be observed under a 500x microscope, while others require magnification of several thousand times or more. Additionally, due to variations in the density of fiber accumulation, the structural conditions between fibers (parallel or crisscrossed), along with the depth of color caused by the amount of iron content, the stage of fiber development during mineralization, the types of trace elements, and other coexisting minerals, jade materials vary greatly in appearance and quality. It is now understood that the thickness of the fibers and their density of accumulation are directly proportional to the density of the jade material. This means that the finer and more densely packed the fibers, the higher the density of the jade, resulting in a better-polished sheen. In natural minerals, its toughness is second only to that of black diamonds. However, there is no objective standard for evaluating or judging its grade or value, which is why “gold has a price; jade is priceless.” The prehistoric tribes living in East Asia, with their rich practical knowledge, selected nephrite, a type of amphibole, from the vast array of natural stones as their treasured object, which is truly admirable.

Naturally, ancient people could not have recognized or identified jade according to modern mineralogical standards. According to the Analytical Dictionary of Characters (or Shuowen Jiezi in Chinese): “Jade, the beauty of stones, has five virtues.” This represents the understanding of jade by ancient Chinese before and during the Han Dynasty, reflecting the ideological recognition of jades social attributes beyond its natural properties. From this, it can be inferred that similar concepts existed among the ancestors of the ancient Chinese and the various prehistoric tribes in East Asia. The word “virtue” is generally understood as the noble quality of peoples social behavior. Different tribes or tribal groups may have different virtues, so the materials chosen by prehistoric tribes to be revered as jade could belong to different types of minerals. According to The Classic of Mountains and Seas, there were over two hundred jade-producing locations, significantly more than the known sources of nephrite today. This suggests that more than one type of mineral was recognized as jade at the time, indicating that during the prehistoric period, different minerals were chosen as jade by different tribes, with nephrite eventually being esteemed as the true jade through a long process of selection. Regarding the meaning of “beauty,” we can set aside any explicit interpretation of beauty itself and note that characters derived from jade or associated with jade in Chinese bear connotations of goodness, perfection, nobility, purity, and sanctity, almost exclusively positive and free from any negative implication. There are nearly 70 characters related to jade in the Analytical Dictionary of Characters, reflecting the status of jade in the early Chinese character system from a side aspect. The clarity of the meaning of jade in the Chinese character system is a significant feature of the Chinese nations tradition of loving and venerating jade. It also vividly reflects the function and status of jade and jade artifacts in society at the time of or before the formation of Chinese characters.

It is well known that in Chinese characters, those related to wealth are derived from the characters for gold or shell, with the exception of the character 寅 (pronounced “yin”), which combines jade and shell. Apart from a few terms like 金玉滿堂 (pronounced “jin yu man tang,” a hall filled with gold and jade) that emerged very late, almost all words derived from or related to jade have nothing to do with money or wealth, indicating that the meaning of jade was defined before the appearance of a civilization marked by the accumulation or plundering of money or wealth. Jade was deified by the prehistoric tribes of East Asia, which, in another sense, can be considered as the materialization of an Eastern ideological form with primitive worship as its content.

Jade is one of the first ancient objects studied in China, and the study of ancient jade was included as a subject of epigraphy starting from the Northern Song Dynasty. Porcelain, bronze, jade, and stone are the basic categories of traditional Chinese studies of ancient objects. In recent years, a prehistoric jade axe was found placed outside the stone threshold of a Northern Pagodas celestial palace from the Liao Dynasty in Chaoyang, Liaoning, indicating it was discovered before the pagodas construction. In the mid-1980s, a cache of Wu culture jade artifacts discovered in Yancun near Suzhou included Liangzhu culture jade bi, and a jade cong cut open as material, thereby dating the discovery of prehistoric jade artifacts to before the 4th or 5th century BCE, which is fifteen centuries earlier than the emergence of epigraphy.

Since epigraphy aims to “verify history and supplement history” as a field of textual research, it relies primarily on written records, and jade artifacts, lacking the extensive inscriptions found on bronze vessels or steles, are relegated to a “lesser” status. Although the study of epigraphy cannot cover prehistoric jade artifacts that lack documentary records, such artifacts continue to be discovered. For example, prehistoric jade artifacts currently housed in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. were acquired from Shanghai in the early 20th century, with many prehistoric jade pieces recorded in Wu Dajings Study of Ancient Jade. Both the Beijing and Taipei Palace Museums have prehistoric jade artifacts in their collections that have been inscribed with imperial poetry by Emperor Qianlong. Additionally, many prehistoric jade artifacts have been replicated or re-engraved, and without having seen similar prehistoric artifacts, it would be impossible to create such closely resembling shapes and patterns. For instance, an official kiln of the Southern Song Dynasty produced a qiong-style bottle that closely resembles Liangzhu jade cong, possibly serving as evidence that Liangzhu jade cong had been discovered during the period when the Southern Song Dynasty established its capital in Hangzhou. After hundreds of years of epigraphic research, a Chinese ancient jade research system has been established, centered around collection, appreciation, and artifact verification, which has also spurred the antique trade focused on transactions. Under its influence, from the early 20th century to the late 1930s, ancient jade became one of the hotspots in the international craze for collecting Chinese antiques. For example, in 1939, Huang Juns Preliminary Collection of Ancient Jade Diagrams included a jade piece from the Hongshan culture; many foreign museums often display Chinese prehistoric jade artifacts collected during this period. Recently, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London selected ten prehistoric jade pieces, including inscribed bi and cong, from Chinese items acquired in 1936.