Typhoons’ effect, stock returns, and firms’ response: Insights from China

2024-05-13LixiangShaoandZhiZheng

Lixiang Shao ✉, and Zhi Zheng

Department of Statistics and Finance, School of Management, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China

Abstract: This paper examines the impact of typhoons in China on the stock returns of Chinese A-share listed firms and the responses of their managers.Based on a sample of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2003 to 2018, we find that the occurrence of typhoons causes significant negative effects on the Chinese stock market, both economically and statistically.We use an event study approach to test the impact of typhoons directly, and we sort the stocks into different portfolios to examine the sensitivity of the typhoons’ effect to different factors.We also investigate the responses of firms’ management to damaging disasters using a difference-in-differences method with multiple time periods.We discover that firms in the neighborhood area are willing to take precautions, including decreasing the current debt to total debt ratio and increasing the ratio of long-term borrowing financing to total assets.Furthermore, firms’ overreactions will disappear as the number of attacks increases, and the rationality of this overreaction needs further research.

Keywords: typhoon; asset pricing; Chinese stock market; firms’ response

1 Introduction

Due to the influences of the geological structure, natural ecology, and climate change, natural disasters have gradually increased in recent years[1].The impact of natural disasters and the problem of how to address them have attracted widespread attention from all walks of life.In 2016, the UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, remarked that “investors need to know how the impacts of climate change can affect specific companies, sectors and financial markets as a whole” at a UN Foundation Investor Summit on Climate Risk①http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2016/01/ban-kimoons-remarks-at-investor-summit-on-climate-risk/.In 2021,the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference reached a new climate agreement, the Glasgow Climate Pact, to raise awareness of the risks of climate change and accelerate the transition to a low-carbon and green development model.All the signs indicate that extreme disasters, such as earthquakes,storms, and typhoons, have enormous impacts on society as a whole.Individuals, companies, and government are all involved.

Numerous studies have confirmed significant damage to both macroeconomic stability and regional development.Therefore, here comes the question, how does the stock market respond to the shock? How about firms and managers? In recent years, there has been a growing body of literature studying the implications of natural disasters on investors and corporate management.Our study explores the impact of disasters from the above two aspects.Investors and firms’ managers are both important participants in coping with natural disasters.They are both the non-macroeconomic parts of the capital market.First, we examine the impact on the Chinese stock market to explore the loss for companies.Second, we investigate managers’ responses when firms are facing physical risks caused by typhoons.We use typhoons making landfall on the Chinese mainland as a quasi-natural experiment in this study.

The typhoon disaster is one of the most frequent and serious meteorological disasters affecting the eastern coastal areas of China.According to statistics from water conservancy and flood control authorities, there are 428 typhoons making landfall in China from 1949 to 2010, with an average annual rate of 6.9.From 2011 to 2018, there are an average of 7.34 typhoons making landfall in China every year, causing 26600 houses to collapse, 20.604 million people to be affected, and about 54 people to die.In recent years, the frequency and intensity of extreme weather and climate events have increased due to global climate change.The heavy rainstorm that struck Zhengzhou on July 20, 2021, serves as a notable example.A primary cause of this disaster was the severe Typhoon In-Fa.

Typhoons are well suited for our purpose for the following reasons mentioned in Ref.[2].First, the occurrence of typhoons has its specific propensity, and we cannot obtain information about the next typhoon from the existing typhoon information in advance.Second, the occurrence is exogenous to individuals, firms, and managers.Therefore, the relevant reactions we observe cannot easily be attributed to unobserved heterogeneity or reverse causality.Finally, the typhoon is a disaster with apparent regional tendency and inflicts heavy damage to the affected region in China.Therefore, we design a difference-in-difference strategy to quantitatively assess the impact of the typhoon.

We document two main findings.First, we examine the effect of severe weather events on the Chinese A-share stock market.It is almost universal for A-share stocks across the country to show a significant negative abnormal return within 30 trading days of a strong typhoon landfall.Further, we find that stocks with smaller sizes and lower values are more vulnerable to strong typhoons in the short term.To further depict the characteristics of investor reaction, we sort the stocks into different portfolios by market equity and earning-price ratio.Market equity and earning-price ratio are two firm-level characters identified as return predictors for size and value anomalies.A more pronounced size effect is obtained for the size anomaly when we exclude the bottom 3 0% firms according to Ref.[3].This result is slightly different from the US market.The smallest 30% of firms in China are impacted mildly, while those in the US are impacted more dramatically compared to the results from Ref.[4].For the value factor,the value stocks perform better than the growth stocks.Moreover, we investigate other influencing factors, such as industry and type of ownership.

Second, for firms’ managers, we show that managers of firms in the neighborhood area are willing to alter the firms’debt structure rather than increase cash holdings for risk reduction.Based on a difference-in-difference strategy, we divide the firms into three groups in terms of geographical distance①The breaking points are 250 km and 500 km.The disaster zone group includes the firms within 250 km of the landing city; the neighbor group includes the firms which are located less than 500 km and more than 250 km away from the landing city; the far group includes the firms which are located more than 500 km away from the landing city..We primarily focus on a timeframe extending from two calendar quarters prior to the disaster, to two quarters after the disaster.First, we find that firms in the neighborhood will decrease their current debt and increase their longterm borrowing at the same time after the disaster compared to distant firms.Managers are willing to take these actions to help firms mitigate liquidity risk.Next, we investigate the learning behavior of managers.The phenomenon of changing firms’ debt structure will diminish as the number of attacks increases.Finally, we compare the firms’ performance between the neighborhood and far area, and no significant differences are presented.The result further validates the use of heuristics by managers to do a risk assessment.That is, the managers near the disaster zone instinctively take steps to hedge against the risk, even though it later appears that they have not suffered severer damage.They make excessive risk assessment mistakes because they rely on intuition and ignore part of the available information.

We contribute to the literature in two major ways.First,there is limited empirical research on specific firms’ implications of such climate risk.This paper contributes to this endeavor by studying the impacts of climate disasters on the Chinese stock market and firms’ financial health.It combines with the relevant characteristics of the Chinese capital market and demonstrates that China’s market has its own specific political and economic features quite different from those in the US and the rest of the world.Second, the study offers quantitative estimates of the effect of natural disasters on firms’ responses using a sample of typhoons as a quasiexperiment from 2003 to 2018.This paper provides new evidence for managers’ overreaction to salient risks by studying the change in debt structure among different areas.We also explore whether firms’ managers will learn from the events,and the result is in line with the availability heuristic hypothesis[2].Based on our research, investors and firms’managers can implement targeted measures to mitigate the losses from climate disasters.We identify the stocks most affected by climate disasters; this analysis should prompt these firms to heighten their awareness of climate risks.Consequently, firms and investors are likely to adjust their strategies accordingly.Moreover, managers can be more aware of whether the decision is an overreaction, so as to make better decisions to reduce the cost of capital.In general,our study is a valuable guideline for investors and management decision-making.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.Section 2 is the literature review.Section 3 describes our data and methodology.The empirical results are subsequently presented and discussed in Section 4.Finally, Section 5 concludes.

2 Literature review

Our paper is mainly related to the performance of different participants in capital markets when disaster strikes, such as investors on financial choice and firms’ response.In this section, we briefly go over the papers that study: (a) the impact of natural disasters on the stock market and (b) firms’ responses to natural disasters.

2.1 Natural disasters and stock market

First, we can see that much previous literature has tended to study the short-term or long-term impact of disasters on macroeconomic growth[5-11].The literature on the effects of natural disasters on the microlevel or stock market is limited so far.Specifically, microlevel studies at the level of the individual,household, or firm are useful for determining the target in terms of disaster management policy[12].Shan and Gong[13]take the Wenchuan Earthquake as a natural experiment, and find that firms with headquarters near the earthquake’s epicenter experience significantly lower stock returns than other firms following the earthquake.Furthermore, their results suggest that investor sentiment may play a role.Bourdeau-Brien and Kryzanowski[14,15]find that major natural disasters induce abnormal stock returns and return volatilities, and natural disasters cause a significant increase in financial risk aversion.The rise in risk aversion is regional but widespread enough to affect asset prices.They suggest that these results are consistent with an emotional-response story.Lanfear et al.[4]document strong abnormal effects due to US landfall hurricanes over the period of 1990 to 2017 on stock returns and illiquidity across portfolios of stocks sorted by market equity(ME), book-to-market equity ratio (BE/ME), momentum,return-on-equity (ROE), and investment-to-assets (I/A).From the above literature, we find that natural disasters can affect the stock market, and investor sentiment may play an important role in this case.Especially in China’s stock market,individual retail investors are the most likely sentiment traders and the major participants[3].

Furthermore, some research has noted that climate change risk caused by natural disasters is an important factor affecting stock markets[16-19].Santi[20]believes that both institutional and retail investors have not yet fully priced climate risks and opportunities into their portfolios.Additionally, investors’ climate sentiment is attracting significant public interest.Wu et al.[21]suggest that disclosures of climate-related information can help the stock market to price climate risk more efficiently.Zhang et al.[22]find that individual investors in the Chinese stock market have incorporated climate risk into their investment decisions.Ma et al.[23]show that individual stock returns comove more with market returns when there are climate disasters such as hurricanes and floods.Meanwhile, they point out that climate events have a greater impact on comovement in stocks with greater sensitivity to their local economy and higher information asymmetry.Recently,Venturin[24]reviews how climate change could be considered an additional source of market risk and concludes by illustrating further directions for both empirical and theoretical research in the field of climate finance.

China, as the world’s largest developing country, is also deeply affected by climate disasters.Developing countries such as China generally face greater physical risks arising from natural disasters.Extreme weather, such as typhoons and rainstorms, can influence enterprise production.The performances are the loss of enterprise assets, the decline of short-term production capacity, the decline of profitability,and the tense and pessimistic mood among investors.Then,the disaster will affect the stock price of enterprises and bring investment risks.Zhang[25]demonstrates that investors are sensitive to climate-related physical and transition risks, and“green” (“brown”) firms are rewarded (penalized) by the market when climate risks increase.Besides, China’s political and economic environments are also quite different from those in the US and other developed economies.In this paper, we provide further evidence of the impact of climate risk on the Chinese stock market by linking certain related factors in China constructed by Ref.[3].

2.2 Natural disasters and firms’ response

Next, let us focus on the firms’ response to natural disasters.Overall, the literature on this subject is inadequate.It was not until recent years that more and more firm-level research began to emerge.

Firstly, much of the literature has documented the negative impact of disasters on the performance of companies in the target region.Gunessee et al.[26]use two major natural disasters as quasi-experiment, namely the 2011 Japanese earthquake-tsunami (JET) and Thai flood (TF) to examine natural disasters’ effect on corporate performance and study the mechanisms through which the supply chain moderates and mediates the link.They find that only JET caused negative effect, further quantified as short-term and long-term.Moreover, they document that inventory matters and suppliers only exhibit a moderating influence.Cainelli et al.[27]take the sample of the sequence of earthquakes that occurred in 2012 in the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna to examine whether the localization of a firm within an industrial district mitigates or exacerbates the economic impact.They find that the earthquake reduced turnover, production, value-added,and return on sales of the surviving firms.In addition, the debt over sales ratio grew significantly more in the firms located in the areas affected by the earthquake.They also suggest that the negative impact of the earthquake was slightly higher for firms located in industrial districts.Hsu et al.[28]take the sample of the US market and empirically measure the impact of natural disasters on firm-level operating performance.Their discoveries verify that technology diversity could mitigate natural disaster risks.Some scholars put forward different views as to whether natural disasters will definitely bring negative economic effects.Noth and Rehbein[29]study the effect of the 2013 flooding in Germany and find that the disaster has robustly positive effects on firm turnover and cash and reduces firm leverage.They infer that this effect may be the result of learning from a previous disaster.Okubo and Strobl[30]investigate the damaging impact of the 1959 Ise Bay Typhoon on firm survival and survivor performance in Nagoya City, Japan.They document that firms in retail and wholesale were less likely and firms in manufacturing more likely to survive after the disaster.Surviving firm performance is heterogeneous across sections.

As to what concerns the studies focusing on China, we first recall Elliott et al.[12], who quantify the impact of typhoons on manufacturing plants in China.They calculate the precise damage caused by typhoons of each plant based on a wind field model.Their results reveal that the impacts on plant sales can be considerable.Meanwhile, they remind that the affected companies will take measures such as an increase in debt and a reduction in liquidity as a cushion.In their research design, they restrict the sample to coastal plants.Sun et al.[31]analyze the impact of climate change risks on China’s mineral listed companies.They find that climate change risks have both positive and negative effects on the financial performance of mining companies, and that mining companies with different types of resources have different sensitivities to climate change risks.Pu et al.[32]examine the impact of lean manufacturing (LM) on the financial performance of companies affected by the Rumbia typhoon disaster.Their findings reveal an inverted U-shaped relationship between LM and financial performance in the context of emergency.

Moreover, several existing articles have explored the impact of shocks on corporate policies.Dessaint and Matray[2]find that the sudden shock to perceived liquidity risk leads managers to increase corporate cash holdings.That is, managers of unaffected firms respond to a hurricane in their proximity by increasing corporate cash holdings.Alok et al.[33]examine whether professional money managers overreact to large climate disasters.They find that managers in the neighboring areas underweight disaster zone stocks more than distant managers, and that the phenomenon will gradually disappear as time goes by.What is more, a recent paper investigates the impacts of natural disasters on security analysts’earning forecasts for affected areas in China[34].Its key findings show that analysts’ optimism significantly decreases for firms located in neighboring areas, and that the judgment is not rational.

In our paper, our sample extends the reach beyond coastal firms and focuses on the major typhoons from 2003 to 2018.At the same time, we use quarterly rather than annual data to identify relevant changes in firms.The results have higher possible precision than those of the previous studies.In addition, our paper is related to the existing studies of Dessaint and Matray[2]and Alok et al.[33], in which a multiperiod difference-in-difference strategy is employed.We also focus on the firms near the disaster zone that are not directly affected.The difference is that we examine managers’ decisions from the debt structure angle rather than cash holdings.We mainly focus on two ratios: current debt to total debt ratio and the ratio of long-term borrowing financing to total assets.From previous research, we know that extreme disasters are accompanied by powerful destruction.Firms near the disaster zone cannot predict the extent to which they will be affected by such disasters.Generally, neighborhood firms may take precautions to manage such risks.In our paper, we examine the two ratios to observe neighborhood firms’ responses.The decrease in current debt to total debt reflects that the short-term debt repayment pressure of enterprises has been mitigated.The increase in long-term borrowing to total assets implies that firms may respond to sudden short-term risks by increasing long-term capital.

3 Data and methodology

3.1 Typhoon data

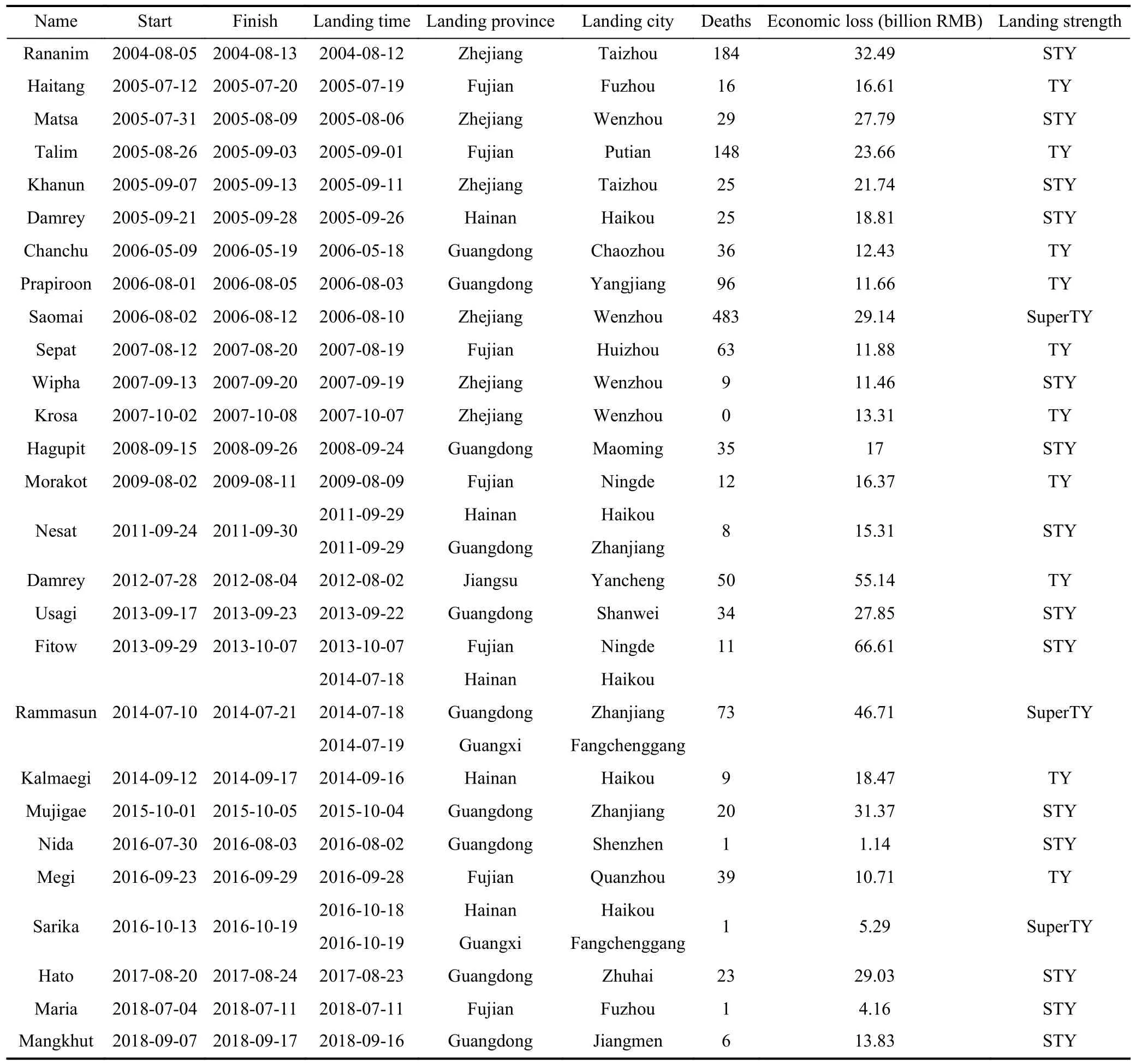

We obtain the names, dates, city locations, deaths, economic loss, and landfall strength of the main typhoons making landfall in Chinese mainland from the Yearbook of Meteorological Disasters in China and Baidu Wikipedia.We restrict the list to typhoons from 2003 to 2018 because there are many missing quarterly financial data for listed firms and missing information for typhoons before 2003.However, many disasters may not be severe enough to affect the stock market and firms’ managers in China.Thus, we consider a typhoon disaster to be “major” when its first landing strength is “STY” and“SuperTY”①The tropical cyclones in the South China Sea and the northwest Pacific Ocean are divided into six grades according to the maximum average wind speed near the center of the bottom.“STY” and “SuperTY” are typhoons whose wind grade is above 14.We eliminate the typhoons occurring during China’s National Day holiday., and a typhoon is “minor” if its first landing strength is “TY” and its damages (adjusted for CPI) are higher than 10 billion RMB.The summary statistics of these typhoons are presented in Table 1.In this paper, the main results are based on the “major” typhoons②The detailed comparison between major and minor typhoons and the regional effect of the typhoons can be found in Supporting Information..In Section 4.3, we focus on typhoons with total direct damages (adjusted for CPI) above 25 billion RMB when investigating the firms’ response to ensure that the event is sufficiently salient.

3.2 Stock data and financial data

We aggregate accessible stock returns and financial data with all listed A-share firms in the Chinese mainland from the CSMAR database.Besides, we require all firms to be public for more than six months and exclude stocks that are “ST”,“*ST”, and “PT”.We restrict our samples to non-financial firms.

Two main firm-level accounting variables are market equity (ME) and earning-price (EP) ratio.We calculate the abnormal returns of different portfolios sorted by return-inequity (ROE), investment-on-assets (I/A), and momentum in Appendix A.3.A firm’s size is measured as the stock’s market capitalization at the end of June each year.We calculate the EP ratio as the fraction of net profit and the stock’s market capitalization at the end of December in the previous year.We rank all stocks by size as of June 30th each year,where we allocate the stocks to three size groups: small stocks(small), middle stocks (middle), and big stocks (big).The breakpoints are the 30th and 70th percentiles of the stock’s market capitalization.We also sort stocks into quintiles for the value factor, and the breakpoints are determined based on the 20th, 40th, 60th, and 80th percentiles.The portfolios are rebalanced at the end of June each year.

To further illustrate the impact of typhoons, we also sort the stocks into different groups by other non-firm level classification indicators, including industry③The industry groups are based on the Guidelines on Industry Statistical Classification of Listed Companies by the China Association for Public Companies.https://www.capco.org.cn/xhdt/tzgg/202305/20230521/j_2023052117544500016846630061707656.html.and the type of the firm’s ownership.

3.3 Methodology

3.3.1 Stock returns

In this subsection, we use the standard event study approach to examine the impact of typhoons on the Chinese stock market, and the detailed procedures are as follows:

Event window.First, we need to identify our event windows of interest.Heavy rainfall, storm surge, and gale are the primary aspects of typhoon disaster threatening human life and the ecological environment.Meanwhile, extreme weather conditions fuel anxiety and fear.Therefore, in this article,we design five different event windows to capture typhoons’effect on the Chinese stock market in different periods.Normally, a warning about the typhoon will be issued by the National Meteorological Centre of CMA approximately three days before landfall.Hence, we use the three days before landing as the first event window, and abbreviate it as [-3,-1].Next, we measure the immediate, short-term, and longterm effects of post-landfall.The corresponding event windows can be abbreviated as [0, 1], [0, 10], and [0, 30].Finally, we design a full-scale event window that starts from the warning day and finishes on the post 30 days after landfall.This event window is abbreviated as [-3, 30].

Estimation period.Next, we should set up an estimation window.In China, typhoon disasters are inherently very local and seasonal.For the most part, typhoons occur between June and October.To avoid contamination of the estimated window as much as possible, we choose March, April, and May as our estimation period.The period includes approximately 90 calendar days, or 65 trading days.It is noted that although November and December are not included in the typhoon season, they are most likely in the event window.

Abnormal return.There are many methods for calculating abnormal returns in the previous literature from the single-factor model to the multifactor model.Our paper selects the single-factor market model.The reason is that we want to observe the portfolios’ anomalous excess returns separately.By design, we can discuss the sensitivity of abnormal returns to other factors separately and see how the returns from the anomaly are affected by extreme weather events.We tested the robustness of the results using the three-factor model in Appendix A.1.

The formula for the market model is as follows:

whereE[εit]=0,Var[εit]=σ2εi.Rit(event)andRmt(event)represent the returns of stockiand market return for dayt, respectively.εitis the disturbance term.αiand βican be estimated by OLS.

The expected stock return can be calculated by:

We can calculate the abnormal return in the event period:

The average abnormal return ofNstocks for daytis:

The most beautiful landscapes looked like boiled spinach2, and the best people looked repulsive3 or seemed to stand on their heads with no bodies; their faces were so changed that they could not be recognised, and if anyone had a freckle4 you might be sure it would be spread over the nose and mouth

Then, the average cumulative average abnormal return forportfolios over the event period is:

Table 1.Summary statistics: major and minor typhoon disasters during our sample period (2003 to 2018).

Testing.Our ultimate objective is to determine if the abnormal return is significantly different from zero.There are two main methods to test it: parametric test[35-37]and nonparametric test[38-40].The results of these two methods are both reported in our tables.

3.3.2 Firms’ response

In this part, we concentrate on the responses of firms’ management facing typhoons.We know that managers will take measures to protect themselves against salient risks.Meanwhile, the perceived risk decreases as the distance from the disaster area becomes longer.Therefore, we assume that the behavior of managers in the neighboring area will be more prominent than that of managers in far areas.As the number of attacks increases, managers near the disaster zone will learn from previous experiences and become more experienced little by little.The psychological shock of disasters will decrease.As a result of managers’ learning behavior, they will be less likely to overreact to typhoons.

We examine the effect of typhoons using a difference-indifference estimation.Our baseline specification is as follows:

whereYitis the related financial indicator of firmiat the end of quartert.We focus on the two calendar quarters prior to two quarters after the disaster in the baseline tests.P ostttakes the value 1 for the disaster quarter and the two following quarters, and 0 for the two quarters before.Controlsi,t-1are vectors of lagged firm-level covariates measured at the end of the quartert-1.Moreover, firm-season fixed effects and yearquarter fixed effects are both included in the formula.We use firm-season fixed effects because the typhoon disaster is seasonal and some financial indicators also fluctuate seasonally.Year-quarter fixed effects are used to control for aggregate macroeconomic changes.

First, we examine the reactions of firms’ managers among different areas.We compare the difference between disaster zone and neighbor, neighbor and far in specific analysis.Therefore, Treatibecomes DisasteriandN eighboriin their respective cases.Themodel is asfollows:

where Disasteritakes the value 1 for the firms in the disaster zone and 0 for the firms in the neighborhood; Neighboritakes the value 1 for the firms in the neighborhood and 0 for the firms in the far area.The cross term reflects the difference between the two sides before and after the disaster.The main dependent variables we are concerned with are as follows:CashRatio , Liquidity , LongDebt , RecTurn , InvTurn, and A.PTurn.

Next, we want to explore whether there is also learning behavior in management.In China, the regions most affected by typhoons are located in the southeastern coastal areas.Therefore, some cities have disaster propensity.In our study,we also design three dummy variables to better examine the relevant actions of firms.First , Second , and More are dummy variables that are utilized in our empirical examination.They equal 1 if the firm is located in the disaster zone or neighborhood area for the first time, second time, and third time (or more), respectively.The regression we estimate is:

We keep the firms if their “Age” is more than one year.All variables are Winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles.The control variables which comprise in the next analysis are Age , SOE , and lagged variables including Size , CashRatio,Lev , SalesGrowth , ROA , NWC , BM , PPE , and INTANG.We report the results of the parallel trend test in Appendix A.2 and the definition of variables in Appendix A.4.

4 Results

4.1 Typhoons’ effect, size, and value factors

4.1.1 Size anomaly

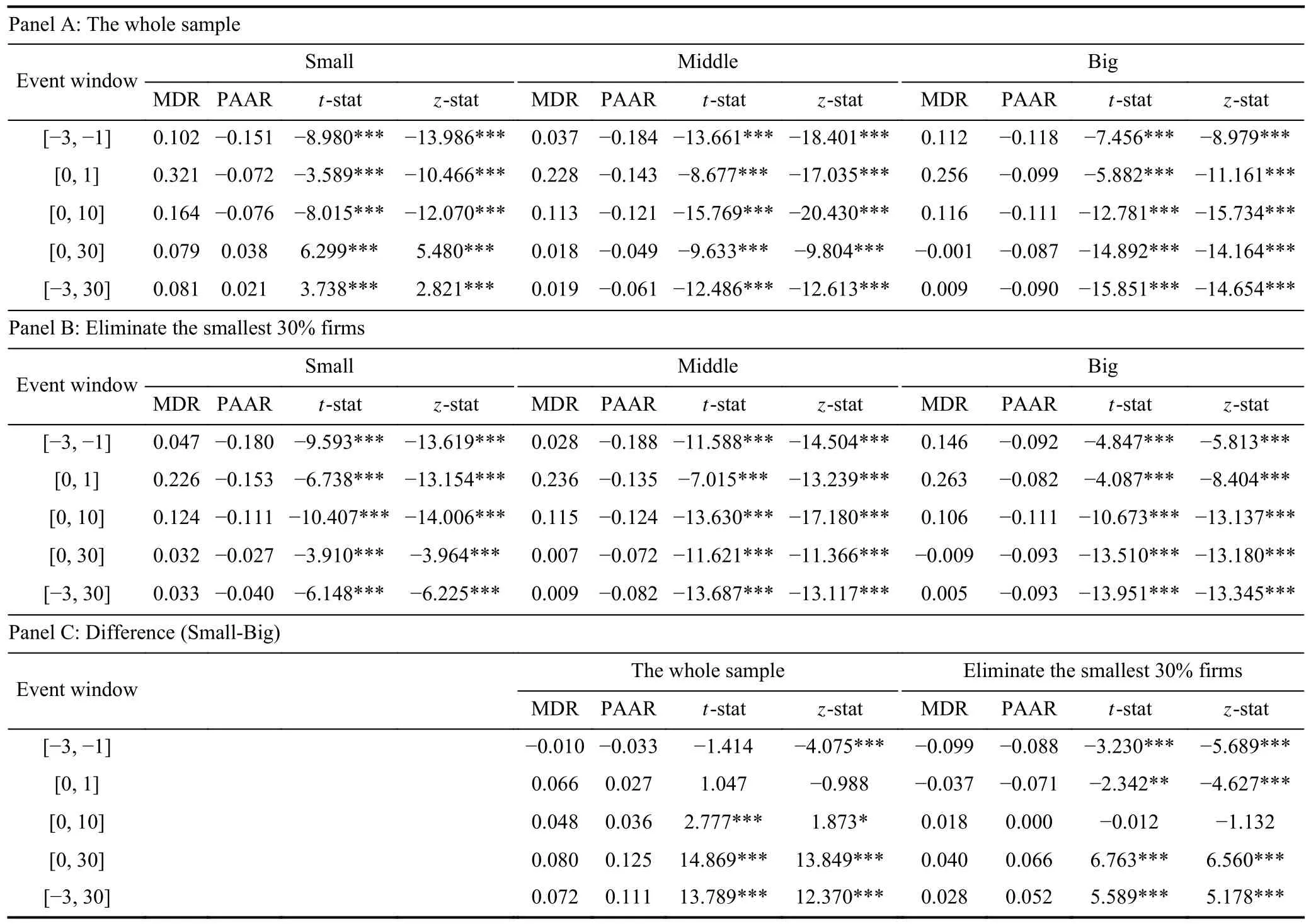

We first examine the effect of the event on the Chinese stock market.In the previous section, we calculate the abnormal returns using the single-factor market model.As we all know,many factors cause market anomalies.It is widely accepted that size and value proxies are two important asset pricing factors in the Chinese stock market[41-44].To better inspect the impact of typhoon events, we sort stocks into different portfolios by these two factors.It is known that the Chinese stock market has unique characteristics, such as growing rapidly with a short history, a high proportion of retail investors, low foreign participation.Recently, Liu et al.[3]construct the size and value factors in China.They find that the bottom firms are valued significantly as potential shells in reverse merges that circumvent tight IPO constraints, so that the size factor can exclude the smallest 30% of firms.In our article, we provide more evidence for this finding.We compare the results sorted by the size factor between the full samples and the samples that exclude the bottom 30%.The results are reported in Table 2.In the following tables, MDR is the mean daily percentage return of the event window, and PAAR is the average abnormal percentage return of the portfolios.

There are several findings in Table 2.First, as shown in Panels A and B, the arrival of typhoons has a significant negative impact on Chinese A-share listed firms in the gross.Second, there is a clearer size effect when we eliminate the smallest 30% of firms from the sample.Generally, small firms, which suffer from high financial leverage and more cash flow problems, should react more sharply to sudden risks.However, from Panel A, we find that the bottom30%of firms are not affected heavily.This result is in line with that of Ref.[3], in which the authors find that the smallest 30%have returns less related to operating fundamentals when compared to other firms, proxied by earnings surprises.We report a clearer firm-size effect in Panel B.In the first two days after the typhoon makes landfall, we observe a negative effect with statistically significant abnormal returns of-0.153% on small firms, -0.135 % on middle firms, and-0.082%on large firms, respectively.Compared to the average daily returns of 0.226% , 0.236% and 0.263%, these abnormal returns are also economically significant.This result suggests that small firms are more sensitive to typhoons in the short term.We can see that the effect of typhoons is weakening over time.Small companies initially overreacted and quickly recovered.These results are also consistent with those of Ref.[4], which find that microcap stocks tend to overreact when hurricanes make landfall and then recover very quickly in the US market.Furthermore, we can observe a significant negative effect on the event window before the typhoon makes landfall in Panel A and Panel B.The results of [-3,-1] are similar in other cases.The result of [-3, 30] is consistent with [0, 30].To save space, we present only the other three event windows to show the difference betweendifferent cases.This result may have something to do with investor sentiment.When the National Meteorological Center issues a typhoon warning, people feel anxious and fearful.

Table 2.Abnormal returns: three portfolios sorted by market equity for the major typhoons.

4.1.2 Value anomaly

In the next work, we explore the response of the value factor to typhoon disasters.Much previous literature has studied the value premium phenomenon of the Chinese stock market.Firms with a high book-to-market ratio are more likely to experience financial distress and are exposed to bankruptcy risk,so they need more compensation for risk[45-47].In China, Ashares exhibit a strong value effect[43,48,49].Generally, investors are willing to pay a premium for stocks with a higher book-to-market ratio.Ng and Wu[50]find that Chinese retail investors prefer holding growth stocks.It seems plausible that the growth stocks of A-shares are overvalued.Lately, Bai et al.[51]find that disasters can help explain the value premium puzzle.When a disaster occurs, value firms are burdened with more unproductive capital, so they are more exposed to the disaster risk than growth firms.In our paper, we use the earning-price (EP) ratio, which performs better than the bookto-market ratio in capturing all Chinese value effects[3], to further examine the typhoons’ effect.In Table 3, we examine the value effect in the event period.

As shown in Table 3, five portfolios are arranged by EP ratio.In accordance with the apparent negative relation between size and abnormal returns, we observe a significant negative effect between value and abnormal returns of portfolios sorted on the EP ratio.For the first two days after landing, the portfolio with the lowest EP ratio (Q1) has an average abnormal return of -0.217 %, while the portfolio with the highest EP ratio (Q5) has an average abnormal return of-0.018 %.This result suggests that the higher the EP ratio of stocks, the more negligible the effect caused by typhoon disasters.This conclusion is confirmed in subsequent short- and long-term event periods.The results seem to differ from those of Ref.[51], but actually, it is reasonable if we think about it from another perspective.In China, value stocks exhibit lower default risk than growth firms, contradicting the usual risk-based rationalization of the value premium[48].This finding might explain the phenomenon of the stock market when typhoons strike.Moreover, the value firms’ business is more stable than growth firms, and they seem to be not very sensitive to perturbation of future outlook.

4.2 Other effects of typhoon disasters

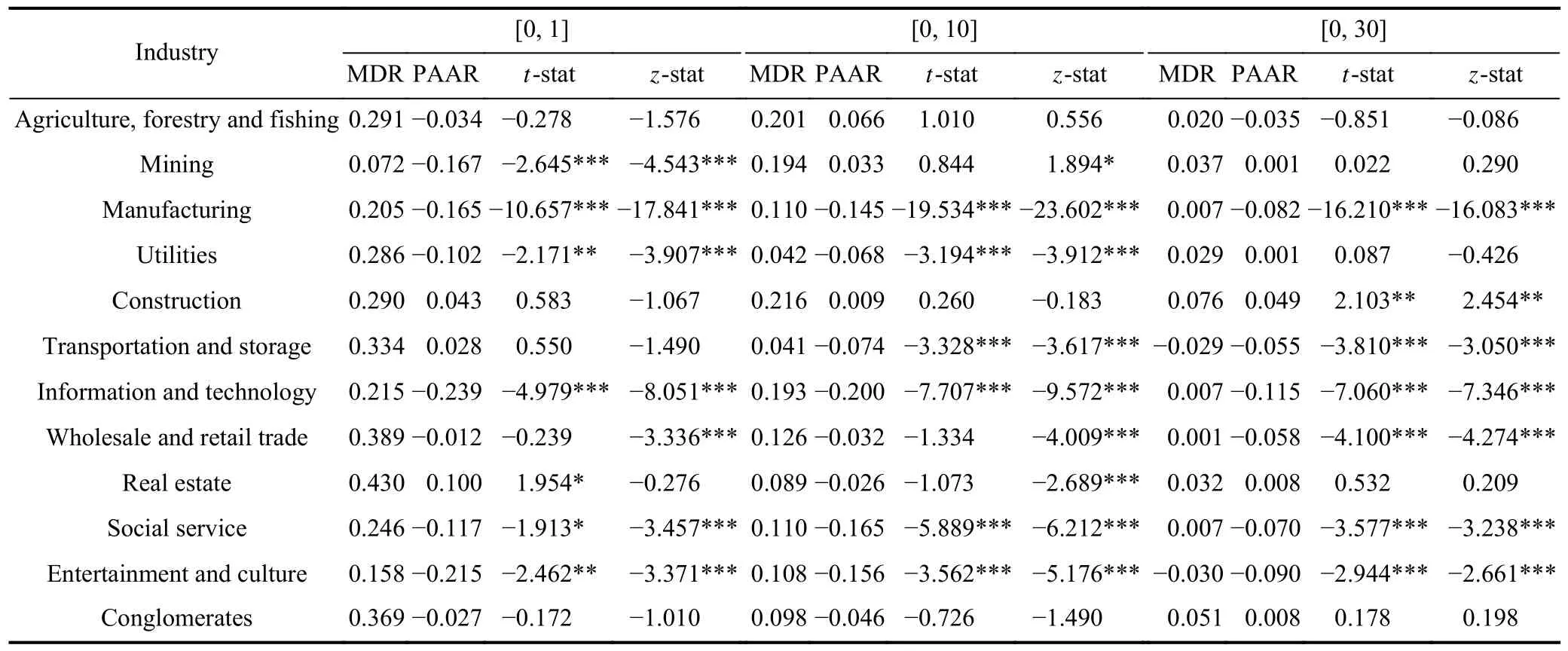

4.2.1 Typhoon effects on various industries

The prior literature finds that natural disaster risk will influence both the insurance markets and the tourism industry[52,53].Lanfear et al.[4]have documented that almost all industries will be influenced by natural disasters.Elliott et al.[12]explore typhoons’ effect on Chinese manufacturing factories’turnover.To further test the relation between the event effect and the characteristics of the affected stocks, we report the results corresponding to portfolios classified by industry in Table 4.In fact, we can intuitively perceive that the different industries can react differently to typhoon events.Overall, the major typhoons bring about remarkable adverse results on most industries in Table 4, especially, “Manufacturing”,“Utilities”, “Information and technology”, “Social service”,and “Entertainment and culture” industries.Moreover, not all industries suffer a negative impact.We discover that the performance of “Agriculture, forestry and fishing”, “Mining”,“Real estate”, and “Conglomerates” industries is not outstanding.It is worth noting that the hardest-hit industries seem not to have a more pronounced negative effect, such as “Agriculture, forestry and fishing” industry.During the typhoon season, fishers are barely able to work, while heavy rains and storm surges destroy crops.However, we do not observe a significant negative effect in the event windows.This result is improbable intuitively.According to news reports, the government seems to be particularly concerned about the impact of the natural disasters on the “Agriculture, forestry and fishing” sector.The government does much work to prevent and subsidize production before and after disasters.This may also be one reason why it seems that it is not impacted seriously.Furthermore, there may be some abnormal factors that have not yet been found.

Another notable point is that the industry categories cannot directly reflect whether the enterprise is low-carbon or“green”.Our results indicate that some industries do not show a significant negative effect as investors perceived these companies to be less sensitive to climate events.

4.2.2 SOEs vs non-SOEs

State-owned enterprises play an important role in all coun-tries, particularly in China.Compared with non-SOEs, the labor productivity and total factor productivity of SOEs are significantly higher[54].Better human capital, more market power, and better management are huge advantages for SOEs.In addition, the current Chinese policy regime also features financial repression, under which banks are required to extend funds to SOEs[55].Li et al.[56]find that SOE managers have less incentive to sustain high stock prices, and highlyvalued SOEs have significantly lower levels of abnormal accruals than highly-valued non-SOEs during the period of high valuation.According to prior literature, compared to SOEs,non-SOEs are more sensitive to the market and more likely to react strongly to external shocks[57,58].In this part, we examine the impact on different ownership structures.We divide the firms into SOEs and non-SOEs.The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 3.Abnormal returns: five portfolios sorted by value factor (EP ratio) for the major typhoons.

Table 4.Abnormal returns: portfolios sorted by industry for major typhoons.

From Table 5, we find that there is a significantly negative effect with an abnormal return of -0.212% for non-SOEs in the first two days after landfall.This negative effect lasted for at least 30 days.For SOEs, the values of negative abnormal returns are smaller than those for non-SOEs.The results imply that the response to typhoons is quite different because of the difference in ownership types.Non-SOEs are more sensitive to extreme events.Our findings confirm the conclusion from Wu et al.[21], who point out that the industry carbon emission, local abnormal temperature, state ownership, institutional shareholding, and dividend payout are important moderators which shape the association of corporate climate risk and the adverse market reaction.

4.3 Firms’ response

4.3.1 Financial health

We have documented that firms’ stock prices suffer a negative effect when typhoons strike.In addition, we have verified that companies face climate risks in Sections 4.1 and 4.2.How then do companies manage these risks? In this section, we begin to investigate typhoons’ impact on firms’ fundamental operations.

First, we examine the firms’ responses and managers’ reactions.Our first interested issue is the changes in debt structure.The main proxy variables are the ratio of current debt to total debt ( L iquidity) and the ratio of long-term borrowing to total assets ( L ongDebt).We also examine the variation of cash holdings using a firm-level variable of C ashRatio.We keep the firms if their “ Age” is more than one year.All variables are Winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles and are defined in Table A4 in Appendix.

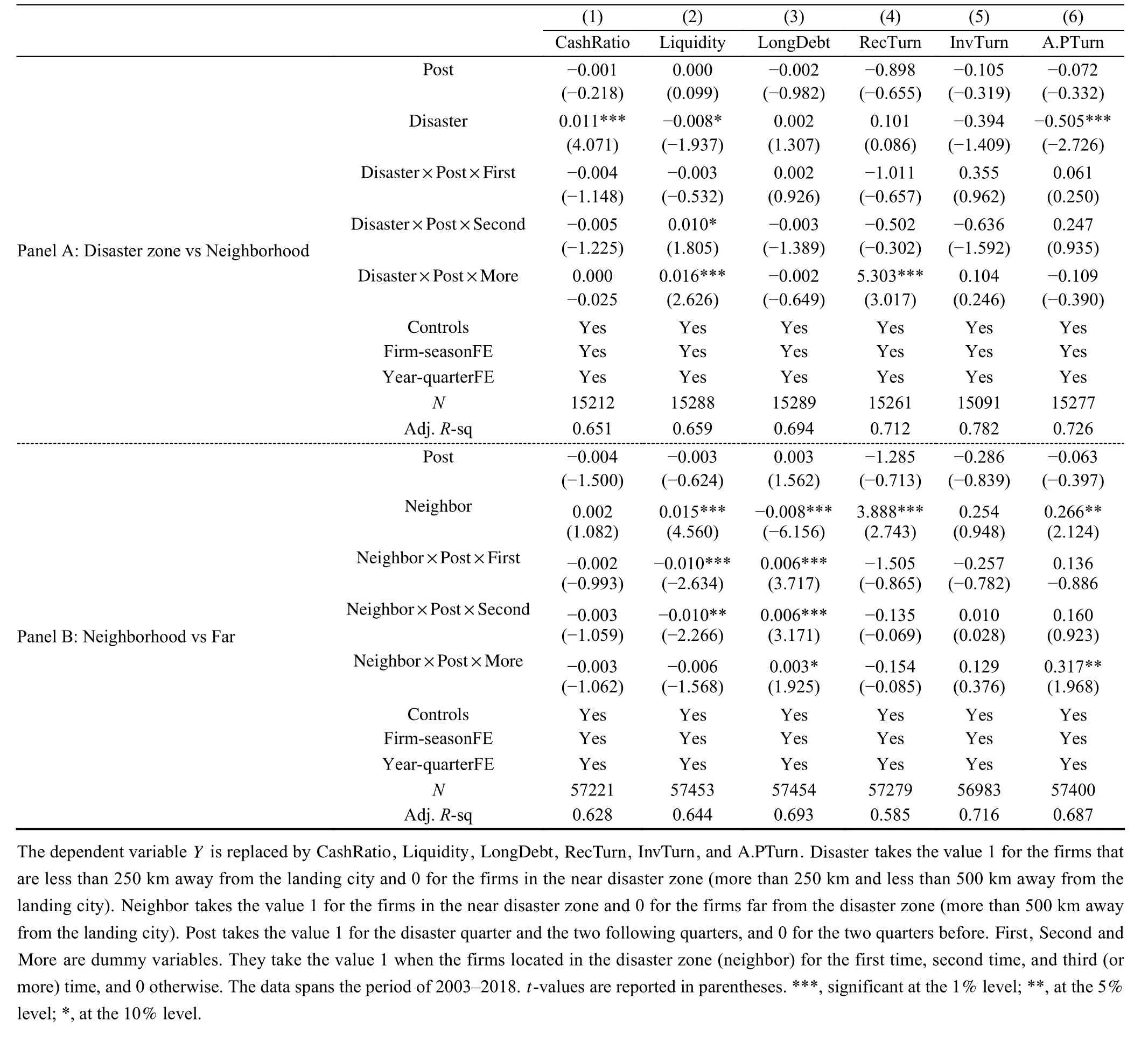

In Columns (2) and (3) of Table 6, we test these two ratios:LongDebt and Liquidity.Prior literature points out that natural disasters can increase financial risks[59].For these enterprises, liquidity risk is an essential part of firms’ risk management.Ramirez and Altay[60]find that firms hold more cash in countries with greater exposure to natural disasters.Dessaint and Matray[2]document that firms will increase their cash holdings just because they are near the disaster zone although they are unaffected actually.These are two methods for companies to manage liquidity risk in the face of natural disasters.In our paper, we investigate two other approaches to managing liquidity risk.In Table 6, we investigate the difference between the disaster zone and neighborhood, neighborhood and the far area, separately.There is no clear difference between disaster zone and neighborhood.However, a significant difference is manifested between the neighborhood and the far area in Panel B.We find that the current debt to total debt ratio decreases and the long-term borrowing to total assets ratio increases after damaging typhoons for the firms in the neighborhood compared to the distant firms.Both indicators reflect the preventive motivation of management.Neighborhood firms want to reduce short-term capital repayment pressure through these measures.

At the same time, we look into the change in cash holdingsamong different areas.From Panel A of Table 6, we observe that the firms in the disaster zone tend to keep a higher cash holding level compared to the neighborhood, regardless of whether there is a typhoon or not.It is not difficult to explain that the disaster zone itself is more prone to be struck by typhoons due to its geographical location.Therefore, the managers in the disaster zone will perform more forms of prevention for fear of a negative external shock compared to the far area.However, the occurrence of typhoons does not prompt management to increase cash holdings significantly,regardless of whether the firms are in the disaster zone or neighborhood.These results support the view that there has been no significant change in cash holdings from an accounting angle.

Table 5.Abnormal returns: the results in SOEs and non-SOEs for major typhoons.

4.3.2 Managers’ learning behavior

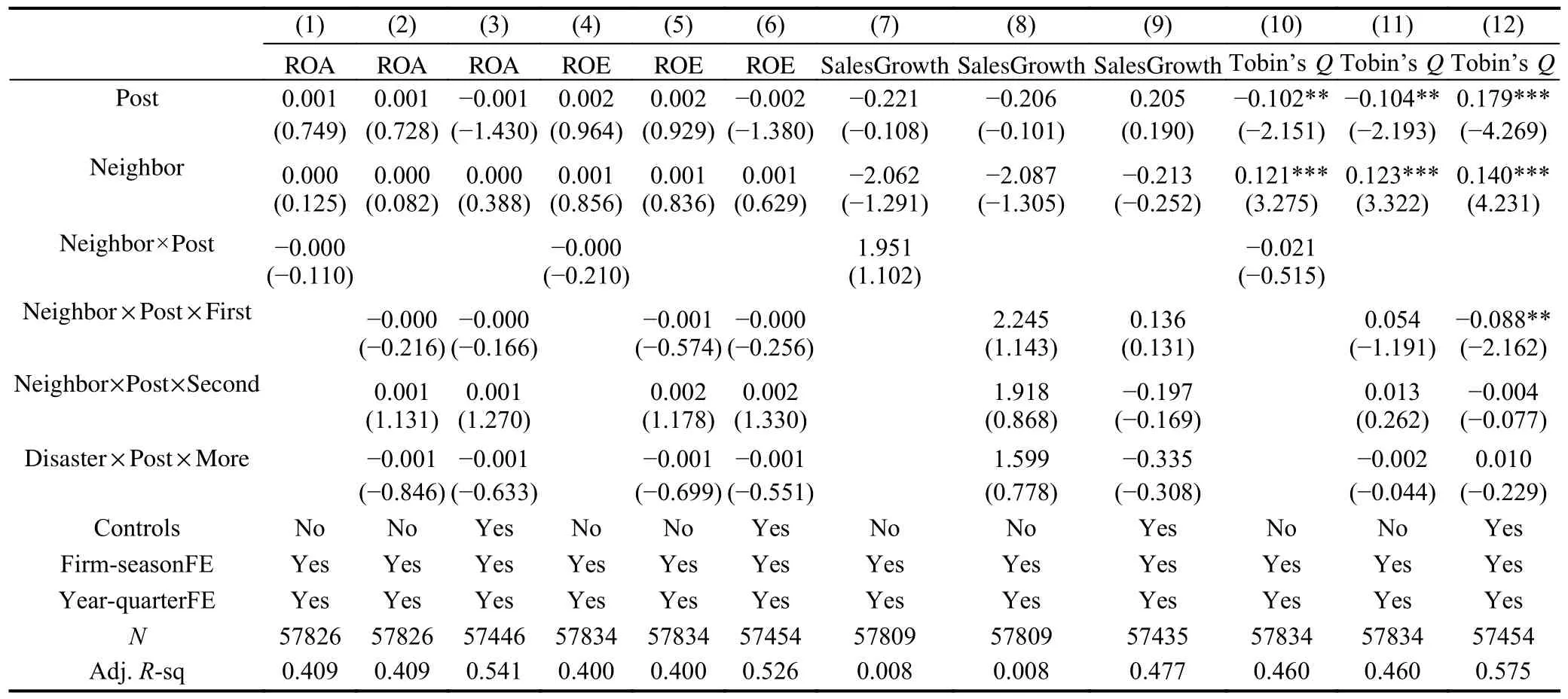

Dessaint and Matray[2]and Alok et al.[33]document that managers can learn, or otherwise become less impacted by salience, and they exhibit less overreaction as they become more disaster-experienced.Noth and Rehbein[29]note that firms that suffered from major disasters in the past will learn from previous experience.Therefore, when they are attacked the next year, the impact is negligible.In Table 7, we report similar results.For Panel A, the results are not significantly different from Table 6.We do not find a significant difference between disaster zones and neighbors for CashRatio and LongDebt.Firms between neighborhood and disaster zones exhibit a significant difference only for Liquidity.This phenomenon may be caused since the typhoon is a kind of shortterm dramatic event.Therefore, it is more apparent for the variation of the neighborhood firms’ short-term financial decision.Now, we turn our attention to Panel B.Columns (2)and (3) reveal that the firms’ liquidity ratio decreases and the long-term borrowing ratio increases when the firms are located in the neighborhood area for the first time, that is, the disasters for managers are new and unusual.The second time,firms’ response is the same as the first time.When this event repeats for the third time or more, the coefficient on the interaction between Treat , Post , and More is lower than the first and second time and is even statistically insignificant.This result is in accord with the availability heuristic hypothesis.When risks are less salient, the overreaction decreases.If managers know the risk and ignore it, this learning behavior may decrease the cost of overreaction[2].Columns (4) to (6) in Table 7 present the variation of the other three turnover ratios( R ecTurn , InvTurn , and A.PTurn).The capital turnover of enterprises is also examined and shows a stable pattern after typhoons.This result is consistent with Table 6.

4.3.3 Financial performance: neighborhood vs far

In this section, we further observe the firms’ impact of typhoons.We compare the performance of different regionsbefore and after typhoons.ROA , ROE , SalesGrowth, and Tobin’sQare the four proxies for firms’ performance in the regression.Table 8 shows us the main results.We compare the difference between neighborhood and far areas.As shown in Table 8, the coefficients are not statistically significant, in particular, the ROA and ROE.The coefficients are not significant both statistically and economically.For SalesGrowth,although the neighborhood is worse off after multiple attacks,it is not significant statistically.For Tobin’sQ, we find that neighborhood firms experience a negative effect for the first time, and then they perform no difference in other cases.In summary, we do not obtain enough evidence to prove that typhoons cause a significant difference in firms’ performance between neighborhood and far areas.We know that neighborhood firms take measures to prevent disaster risk.However,there is no significant difference in the performance between the two areas.This result indicates that managers seem to overreact to external shocks although they are actually not affected.

Table 7.Typhoons’ impact on firms: firms’ response.

Table 8.Typhoons’ impact on firms: firms’ performance (neighborhood vs far).

5 Conclusions

Much of the previous literature on the impact of natural disasters has tended to focus on national or regional effects.In our paper, we take typhoon events in China as a quasiexperiment and explore the impact on the Chinese A-share stock market.Meanwhile, we investigate the typhoons’ effect from the firm level and observe the managers’ reactions facing damaging disasters.

We first examine the impact of the typhoon disaster on the stocks of firms in the Chinese A-share market.We find that stocks with a smaller size and a lower earning-price ratio are vulnerable to typhoon disasters.When we exclude the bottom 30 % of the sample in this paper, the explanatory power of the size factor does indeed increase.The phenomenon is now well understood according to Ref.[3], that is, the fundamental operations of the bottom 30% of firms do not precisely reflect the firms’ returns.The story for value stocks is consistent with Lanfear et al.[4]who point out that not all disasters impact value stocks negatively.These results are robust to a non-parametric test.We also explore other factors such as distance, industries, and type of ownership.

Next, we investigate the responses of firms’ managers.Our findings indicate that managers tend to prioritize altering the debt structure over increasing cash holdings.This result underscores the strategic differences in risk management between the Chinese and US markets.Managers’ learning behavior and managerial overreaction warrant further investigation.We document a waning trend for managers’ reactions along with an increase in the number of strikes.There is no performance difference among different areas, which suggests that the managers exhibit overreaction.

Policymakers, investors and firm managers can also learn from the reported findings about optimal disaster decisions.One thing we do know is that the impact of disasters on society is severe, so the stock market and firms reflect clearly.However, we have not yet concluded whether such measures will be costly for businesses.There is still much uncertainty about whether investors and firms’ overreactions are detrimental to post-disaster reconstruction.Furthermore, the geographical distance of the company headquarters is used to divide the groups in this paper.In fact, the distance of the factory from the disaster zone could be more accurate.In future research, we intend to further explore the costs and benefits of disaster prevention measures and more analytical methods to provide better insights.

Supporting information

The supporting information for this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.52396/JUSTC-2022-0157.It includes three tables.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Biographies

Lixiang Shao is currently a master’s student at the Department of Statistics and Finance, University of Science and Technology of China.Her research mainly focuses on corporate finance.

Zhi Zheng is currently a Ph.D.candidate under the supervision of Prof.Weiping Zhang at the University of Science and Technology of China.His research mainly focuses on longitudinal data analysis.

Table A1.Robustness test: the result of Three-factor model for major typhoons.

t-stat andz-stat are the statistical significance based on thet-test statistic and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, respectively.***, significant at the 1 % level;**, at the 5 % level; *, at the 10 % level.

Event window MDR PAAR t-stat z-stat Panel A: The whole sample (Three-factor model)[0, 1] 0.264 -0.012 -1.202 -10.987***[0, 10] 0.130 -0.013 -2.681*** -8.184***[0, 30] 0.031 -0.004 -1.340 -2.608***Panel B: Eliminate the smallest 30% firms (Three-factor model)[0, 1] 0.240 -0.029 -2.468** -9.920***[0, 10] 0.115 -0.027 -4.758*** -8.598***[0, 30] 0.010 -0.029 -7.861*** -8.397***Panel C: Eliminate the smallest 30% firms & Eliminate typhoons happened in 2008 and 2015(Single-factor market model)[0, 1] 0.149 -0.112 -9.307*** -19.083***[0, 10] 0.170 -0.120 -21.174*** -26.734***[0, 30] 0.031 -0.069 -17.824*** -17.451***

Table A2.Parallel trend test.

The dependent variablesYare L iquidity and L ongDebt.D isaster takes the value 1 for the firms that are less than 250 km away from the landing city and 0 for firms in the near disaster zone (more than 250 km and less than 500 km away from the landing city).N eighbor takes the value 1 for firms in the near disaster zone and 0 for the firms far from the disaster zone (more than 500 km away from the landing city).Pre takes the value 1 for the two quarters before the disaster quarter, and 0 otherwise.Post takes the value 1 for the disaster quarter and the two following quarters, and 0 otherwise.D ispre,Dispost , Neipre , and Neipost are the cross terms.The data spans the period of 2003-2018.t-values are reported in parentheses.***, significant at the 1 % level; **, at the 5 % level; *, at the 10 % level.

(1) (2) (3) (4)Liquidity LongDebt Liquidity LongDebt Panel A: Disaster zone vs Neighborhood Dispre[-2, -1] -0.005 0.000 -0.005 0.000(-1.166) (0.025) (-1.122) (-0.058)Dispost[0, 2] -0.004 0.003**(-1.097) (2.019)Disaster -0.002 0.001 -0.001 -0.000(-0.958) (0.995) (-0.291) (-0.067)Pre[-2, -1] 0.005 -0.002 0.006 -0.003(1.060) (-0.963) (1.435) (-1.729)Post[0, 2] 0.007** -0.006***(2.109) (-4.136)Controls Yes Yes Yes Yes Firm-seasonFE Yes Yes Yes Yes Year-quarterFE Yes Yes Yes Yes N 24456 24457 24456 24457 adj.R-sq 0.650 0.693 0.650 0.693 Panel B: Neighborhood vs Far Neipre[-2, -1] -0.002 -0.000 -0.002 0.000(-0.737) (-0.127) (-0.802) (0.015)Neipost[0, 2] -0.005** 0.003***(-1.972) (3.402)Neighbor 0.008*** -0.004** 0.011*** -0.006***(4.733) (-5.494) (4.843) (-6.350)Pre[-2, -1] 0.003 -0.001 0.002 -0.001(0.657) (-0.649) (0.589) (-0.699)Post[0, 2] -0.003 0.001(-1.093) -0.845 Controls Yes Yes Yes Yes Firm-seasonFE Yes Yes Yes Yes Year-quarterFE Yes Yes Yes Yes N 72908 72909 72908 72909 adj.R-sq 0.629 0.684 0.629 0.684

A.3 Other related factors

In this table, we calculate the abnormal returns of different portfolios sorted by return-in-equity (ROE), investment-on-assets(I/A), and momentum.We first eliminate the smallest 3 0% firms and then divide the stocks into groups following Ref.[4].From Table A3, first we find the higher the ROE, the lower the typhoons’ effect on the profitability factor in the short-term, while the long-term picture is the opposite.There seems to be some similarity with the size effect.For the investment factor, it is clear thatthe short-term response of typhoons is more dramatic.The above two factors are also mentioned in the FF five-factors model.For the momentum factor, the immediate effect is not significant.However, high momentum portfolios perform more negatively as time goes by.

Table A3.Abnormal returns: the results on other related factors for the major typhoons, including ROE, investment, and momentum.

We rank the stocks based on corresponding firm-level variables and split the samples into quintiles.This table reports three different event windows and the expected abnormal return is calculated using a market model.t-stat andz-stat are the statistical significance based on thet-test statistic and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, respectively.***, significant at the 1 % level; **, at the 5 % level; *, at the 10 % level.

[0, 1] [0, 10] [0, 30]Portfolio MDR PAAR t-stat z-stat MDR PAAR t-stat z-stat MDR PAAR t-stat z-stat Q1 (Low) 0.146 -0.142-3.930*** -7.585*** 0.112 -0.075 -4.337*** -6.847*** 0.038 0.002 0.189 0.604 Q2 0.314 -0.069 -1.482 -4.718*** 0.178 -0.067 -2.928*** -5.063*** 0.061 -0.021 -1.579 -1.920*Q3 0.229 -0.107 -2.398** -4.379*** 0.157 -0.102 -4.405*** -5.726*** 0.094 -0.017 -1.166 -1.124 Panel A: ROE Q4 0.260 -0.085 -2.068** -3.988*** 0.179 -0.111 -5.825*** -6.451*** 0.065 -0.074 -5.502*** -5.713***Q5(High) 0.347 -0.059 -1.868 -3.955*** 0.138 -0.173-10.483***-11.275*** 0.009 -0.153-13.747***-13.072***Dif(Q1-Q5)-0.200-0.083 -1.731* -2.801*** -0.026 0.098 4.111*** 3.640*** 0.030 0.155 9.676*** 9.887***Q1 (Low) 0.259 -0.067 -2.473** -7.305*** 0.150 -0.065 -5.228*** -7.640*** 0.040 -0.020 -2.339** -2.113**Q2 0.206 -0.146-5.313***-10.092*** 0.123 -0.105 -8.264*** -11.135*** 0.010 -0.060 -7.391*** -7.008***Q3 0.295 -0.072-2.852*** -7.065*** 0.151 -0.078 -6.087*** -9.161*** 0.023 -0.055 -6.474*** -6.939***Panel B: I/A Q4 0.266 -0.110-4.135*** -8.275*** 0.109 -0.123 -9.439*** -11.615*** 0.008 -0.068 -8.051*** -8.146***Q5(High) 0.210 -0.169-5.751*** -9.626*** 0.076 -0.165-11.811***-13.935*** -0.015-0.096-10.288***-10.006***Dif(Q1-Q5) 0.049 0.102 2.538** 2.854*** 0.075 0.100 5.350*** 6.397*** 0.056 0.075 5.896*** 6.050***Q1 (Low) 0.073 -0.140 -2.222** -4.720*** 0.259 0.019 0.642 -0.754 0.103 0.110 5.447*** 5.234***Q2 0.010 -0.062 -0.791 -2.220** 0.192 0.009 0.282 -0.147 0.096 0.080 3.540*** 3.786***Q3 0.325 0.041 0.526 -0.629 0.263 -0.037 -1.161 -2.177** 0.189 0.069 2.466** 2.008**Panel C: Momentum Q4 0.105 -0.157 -1.992** -2.464** 0.163 -0.128 -3.302*** -4.241*** 0.030 -0.122 -4.463*** -4.546***Q5(High) 0.217 -0.213-3.941*** -5.133*** 0.169 -0.277-10.037***-10.753*** -0.016-0.271-14.180***-13.171***Dif(Q1-Q5)-0.144 0.073 0.865 0.015 0.090 0.296 7.056*** 7.777*** 0.119 0.381 13.176*** 12.913***

A.4 Definition of variables

The definition of variables are shown in Table A4.

Table A4.Definition of variables.

Measure Description Post A dummy variable equal to 1 for the disaster quarter and the two following quarters, 0 for the previous two quarters.Disaster A dummy variable equal to 1 if a firm is in the disaster zone, and 0 if a firm is in the neighborhood.Neighbor A dummy variable equal to 1 if a firm is in the neighborhood, and 0 if a firm is in the far area.First A dummy variable equal to 1 when the firms are located in the disaster zone (neighborhood) for the first time; otherwise, 0.Second A dummy variable equal to 1 when the firms are located in the disaster zone (neighborhood) for the second time; otherwise, 0.More A dummy variable equal to 1 when the firms are located in the disaster zone (neighborhood) more than two times; otherwise, 0.ROA The ratio of net profit to total assets.ROE The ratio of net profit to total equity.SalesGrowth Percentage annual change in division sales.Q Tobin’s The ratio of market equity to total assets.CashRatio The ratio of cash holdings defined as the value of cash and cash equivalent divided by the value of total assets.Liquidity The ratio of book value of current debt to book value of total debt.LongDebt The ratio of long-term borrowing to the book value of total assets.RecTurn The ratio of operating income divided by the average of accounts receivable at the end and beginning of the period.InvTurn The ratio of operating income divided by the average of inventory at the end and beginning of the period.A.PTurn The ratio of operating income divided by the average of accounts payable at the end and beginning of the period.Age The natural logarithm of the number of years the company has been listed.Size The natural logarithm of total assets.Lev The ratio of leverage defined as total debts divided by total assets.NWC The ratio of net working capital defined as the net working capital divided by the value of total assets.BM The ratio of a stock’s book equity to the market equity.PPE The ratio of book value of fixed assets to the book value of total assets.INTANG The ratio of book value of intangible assets to the book value of total assets.SOE A dummy variable equal to 1 if the type of ownership of the firms is state-owned; otherwise, 0.