Influence of Ca addition on the dynamic and static recrystallization behavior of direct extruded flat profiles of Mg-Y-Zn alloy

2023-12-27MriNienerJnBohlenSngongYiGerritKurzKrlUlrichKinerDietmrLetzig

Mri Niener ,Jn Bohlen ,Sngong Yi ,Gerrit Kurz ,Krl Ulrich Kiner ,Dietmr Letzig

aInstitute of Material and Process Design, Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon GmbH, Max-Planck-Str.1, Geesthacht 21502, Germany

b Agnes-Miegel, Str.11, Bad Essen 49152, Germany

Abstract This paper investigates the influence of addition of Ca in a Y-Zn-containing magnesium alloy on the dynamic and static recrystallization behaviors and reveals the formation mechanism of the quadrupole texture during thermomechanical processing.Direct extrusion of flat bands has been conducted at various process conditions to study the difference between the two alloys WZ10 and WZX100 in terms of microstructure and texture development.It can be shown that,Ca addition promotes the DRX of WZ10 alloy.During additional heat treatment,the absence of Y segregation at the grain boundaries and the associated lack of solute drag to the boundary mobility leads to a pronounced grain growth during SRX in WZX100 alloy.Furthermore,it is shown that the addition of Ca to Y-Zn is not beneficial in terms of formability.It is demonstrated that alloying elements can have different effects depending on the recrystallization mechanisms.Partially recrystallized microstructure is a prerequisite at the as-extruded status to form the quadrupole texture and during subsequent annealing,which stands for high formability.

Keywords: Extrusion;Recrystallization;Magnesium alloy;Mg-Y-Zn-Ca alloy;Formability;quadrupole texture.

1.Introduction

The low density of magnesium alloys qualifies them as an ideal material for reducing the weight of structural components.Application of magnesium flat products is difficult due to the limited formability at room temperature and the anisotropy of the mechanical properties.The reason for the limited formability is the hexagonal crystal structure of magnesium and the formation of a strong crystallographic texture during the massive forming process [1,2].Therefore,to improve the mechanical and forming properties of flat products,it is necessary to know precisely how the microstructure(grain size)and texture are influenced by alloying elements as well as by process parameters like the extrusion temperature.It is known that besides texture,the microstructure and so the grain size has also an important factor on mechanical properties [3–6] and on the biaxial formability at room temperature[7–10].To control the microstructure and texture,it is necessary to understand the recrystallization (RX)-mechanisms.During extrusion the dynamic recrystallization(DRX)is dominating the microstructure development and whereas during heat treatment the static recrystallization(SRX)[11,12].Alloy elements such as Yttrium (Y) and Calcium (Ca) are known to modify the RX behavior and thus influence the microstructure and texture of magnesium semi-finished products.

The addition of Ca to several magnesium alloys leads to obstruction of the grain growth dependent on the prevailing RX mechanism [13–17].Hofstetter et al.[18] showed on an extruded Zn-Ca magnesium alloy that the formation of fine and homogeneously distributed intermetallic Ca2Mg6Zn3particles positively affects DRX and limits grain growth by hindering the movement of dislocations and grain boundaries(GBs).For the addition of Y in Zn containing Mg-alloy,Kim et al.[19] reported,that during SRX (rolling with additional heat treatment) the enhanced pinning (solute-drag effect) of dislocations or grain boundaries due to the higher amount of dissolved elements helps to delay recovery and grain growth.But also,for extruded materials,where DRX is the dominating mechanism,Y works as a grain refiner [20,21].In addition,many semi-finished products of Mg alloys containing Y-Zn reveal high formability [22–24].

A decrease in grain size and a weakening of the basal texture can significantly improve the mechanical behavior[3–5,25] and the biaxial formability at room temperature[11,22–24,26,27].It has been reported that there is a clear correlation between the recrystallization mechanisms (static(SRX) as well as dynamic (DRX)) and texture development[28–32].Besides this,alloying elements such as rare earth(RE) are known to be an efficient method for weakening texture during extrusion of Mg alloys [33–35].Especially in combination with Zn,RE but also Y can change the recrystallization behavior and lead to the formation of RE texture components [24,26,29,36],which are also beneficial for the forming behavior.Ca,known as a substitution element for the rare earth elements,also influences the recrystallization behavior,texture development [37–39] and changes the activity of the deformation mechanisms [40,41].Evidence from the literature suggests that texture is the determining factor for high formability.In order to modify the texture,it is important to know the influence of the alloying elements on the static and dynamic recrystallization behavior.

It has been shown that there are many studies that consider the binary addition of Y or Ca into magnesium or ternary alloy containing Zn to improve the microstructure and texture via controlled RX mechanisms,e.g.obstructed grain growth.However,there is no study that shows the influence of Ca addition on the recrystallization behavior of Y and Zn containing magnesium alloy.

In this work the recrystallization behaviors of extruded WZ10 and WZX100 were comparatively studied.To control the as-extruded microstructure,in terms of degree of dynamic recrystallization,the extrusion was carried out at various temperatures and the SRX/ grain growths behaviors of the extrudates were studied during the subsequent heat treatment.The difference between WZ10 and WZX100 in terms of recrystallization behavior and the associated microstructure development is particularly considered,as well as texture development.In addition,the texture is correlated with the formability at room temperature for the heat treated bands.

2.Materials and methods

WZ10 and WZX10 alloys,Table 1,were prepared by using a modified gravity casting technique including directional solidification in a crucible [42].Billets were machined to a diameter of 49 mm and to a length of 75 mm.Solid solution annealing of the cast billets was carried out at 500 °C for 16 h for both alloys.

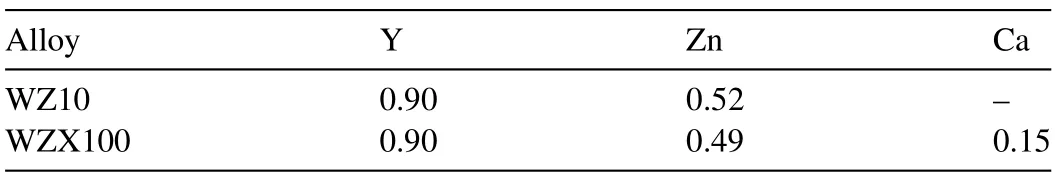

Table 1 Chemical compositions,measured by spark emission spectroscopy,of the investigated alloys in the present study (in wt.-%;Mg in balance).

An 2.5 MN extrusion press from Müller Engineering(Müller Engineering GmbH &Co.KG,Todtenweis/Sand,Germany) was used for the direct extrusion.The flat bands with the cross section of 40 mm x 2 mm were produced at various extrusion temperatures,325,350,375,400 and 450°C,resulting the microstructures with different degrees of DRX during the extrusion.The ram speed of 0.6 mm/s was kept constant.These extrusion conditions correspond to an extrusion ratio of 1:24.5 and a profile exit speed of 0.9 m/min.The extruded bands were heat-treated at 450 °C for 10 min to investigate the microstructure and texture developments during SRX/ grain growth.The samples were air cooled after extrusion and annealing.

Microstructural analysis was performed on the longitudinal sections of the bands using optical microscopy.The samples were ground with SiC paper from 800 to 2500 grit,followed by mechanical polishing using 0.05 μm colloidal silica OPS suspension (Struers) and soapy deionized water.Etching was applied according to Kree et al.[43].For global texture measurements of the as extruded and heattreated bands,samples were mechanically ground and polished to the mid-thickness plane.X-ray diffractometer(X’Pert PRO MRD,Malvern Panalytical Ltd,Malvern,United Kingdom) with Cu Kαradiation and a beam size of 2 × 1 mm2was used to measure 6 pole figures up to a tilt angle of 70° The (0002) and {10–10} pole figures were recalculated using a MATLAB-based toolbox MTEX [44] from the measured pole figures.Electron backscatter diffraction(EBSD) measurements were conducted at the acceleration voltage of 15 kV in a scanning electron microscope (SEM,Ultra 55,Carl Zeiss AG,Oberkochen,Germany).The specimens for EBSD measurements were prepared on the longitudinal sections by electrolytic polishing at -20 °C and 30 V for 30 s in Struers AC2 solution.Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) was applied for the analysis of elemental segregations at the grain boundaries.Samples for the STEM were prepared from the transverse plane of the flat product using a dual beam SEM-FIB microscope,ZEISS Crossbeam 550 L.

The formability was determined by measuring the Erichsen index,using Erichsen tester(Type 145–60,Erichsen GmbH&Co.KG,Hemer,Germany),at room temperature.The Erichsen tests were performed on bands (150×40 mm) using a punch with the diameter of 20 mm with the punch displacement rate of 5 mm/min and blank holder force of 10 kN.The Erichsen index (IE) will given in mm.

3.Results and discussion

3.1.Microstructure

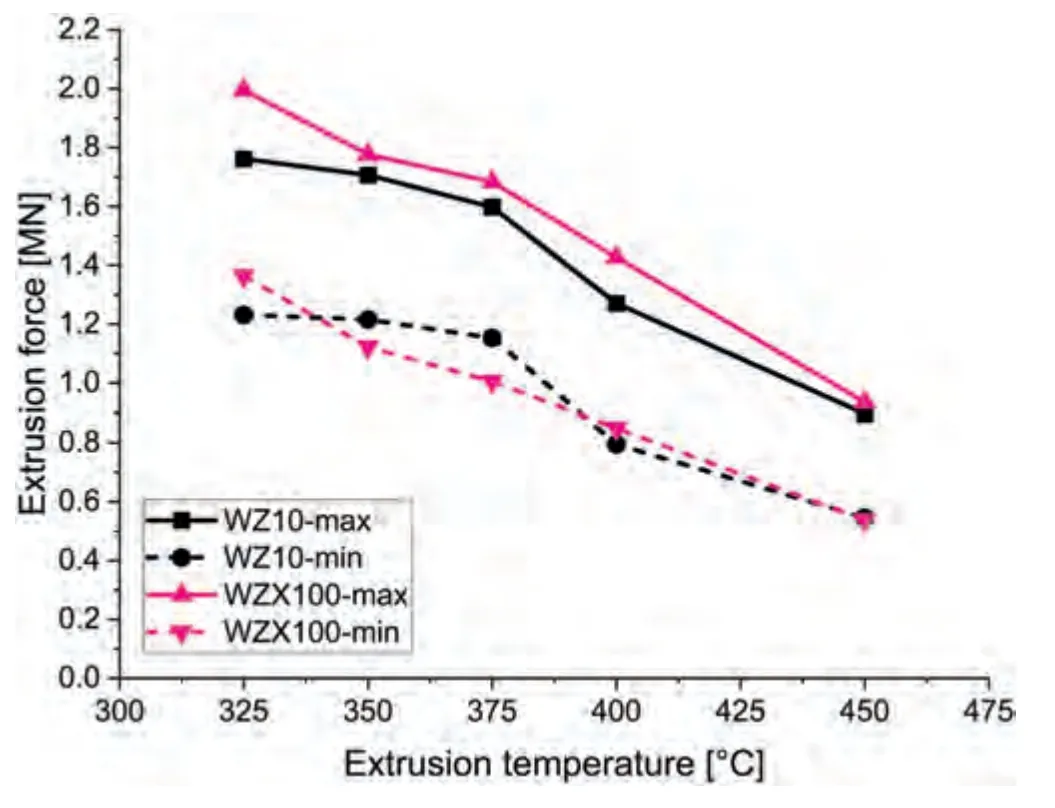

In Fig.1 the extrusion forces at the beginning (max) and at the end stage (min) of all extrusion trials are presented in relation to the process temperature.Due to the direct extrusion process,the force consists of the fractions required for the flow stress and of the friction between billet and container wall.The maximum extrusion force is the force required to start the material to flow at the beginning of the process and the minimum extrusion force correlates with the flow stress,because the friction at the end of the extrusion process can be neglected.Consequently,the minimum extrusion force is more meaningful in terms of the alloy-dependent dynamic recrystallization behavior that takes place during the process.

For both alloys,WZ10 and WZX100,there is a clear difference between the curves for the minimum and maximum extrusion forces depending on the extrusion temperature.The WZ10 shows an almost stationary range in the extrusion forces between 325 °C and 375 °C.In this temperature range,no significant influence of the extrusion temperature on the flow stress is visible.A remarkable decrease in the extrusion forces with increasing temperature can only be observed from an extrusion temperature of 375 °C to 450 °C.For WZX100 it can be found that between 325 °C and 400 °C higher extrusion forces (max force) are required to bring the material into flow.In addition,the flow stress decreases almost linearly with increasing process temperature over the entire temperature range.The alloy-dependent differences in flow stress suggest an influence of Ca on the dynamical recrystallization(DRX) behavior.

During extrusion,large forces and high degrees of deformation affect the microstructure development,such as onset and degree of dynamic recrystallization.In this regard,the extrusion process and subsequent annealing offer the opportunity to investigate the influence of alloying elements and chemical composition on the dynamic and static recrystallization behaviors and associated microstructure development.

Fig.1.Extrusion forces as a function of the extrusion temperature.

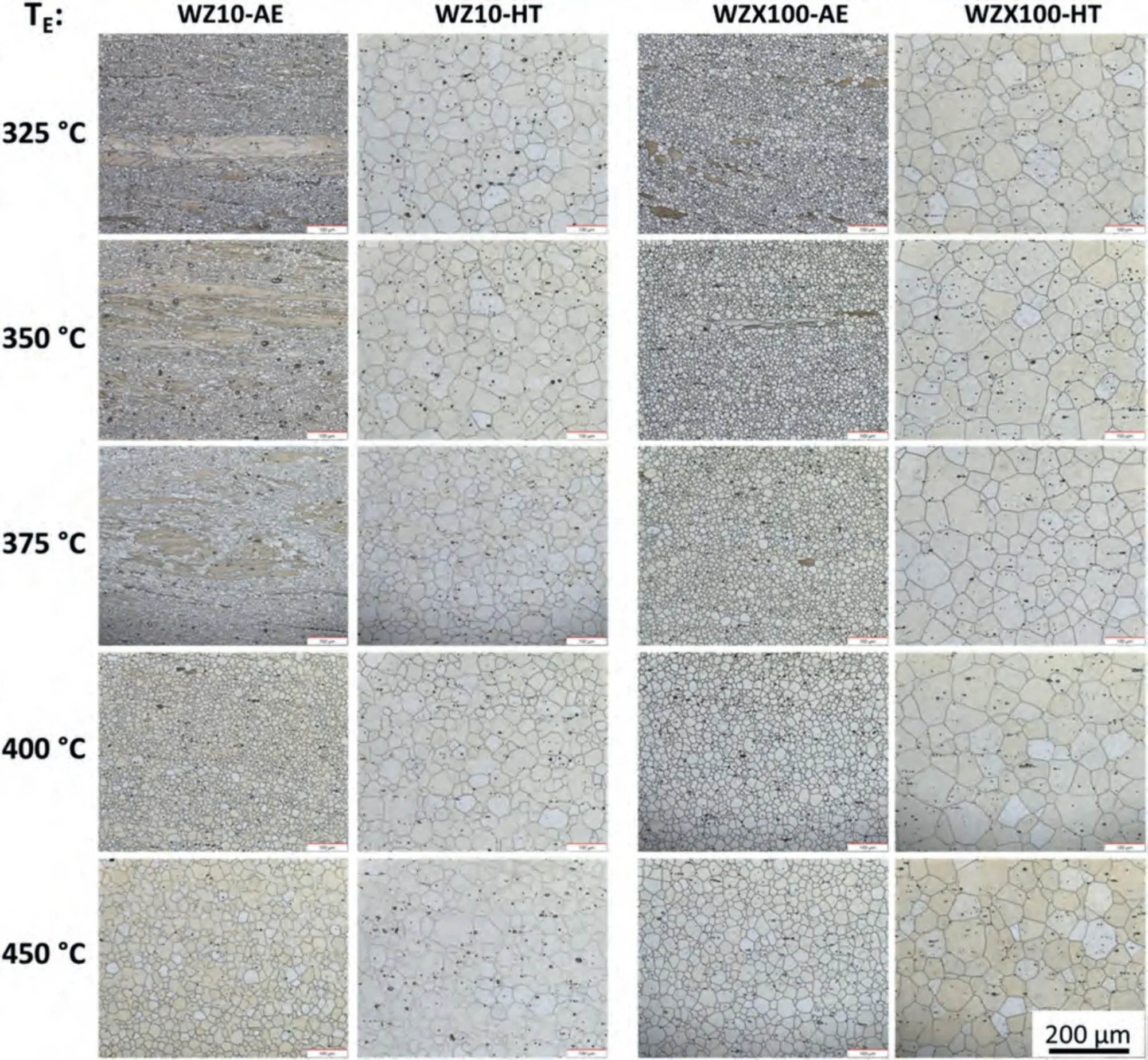

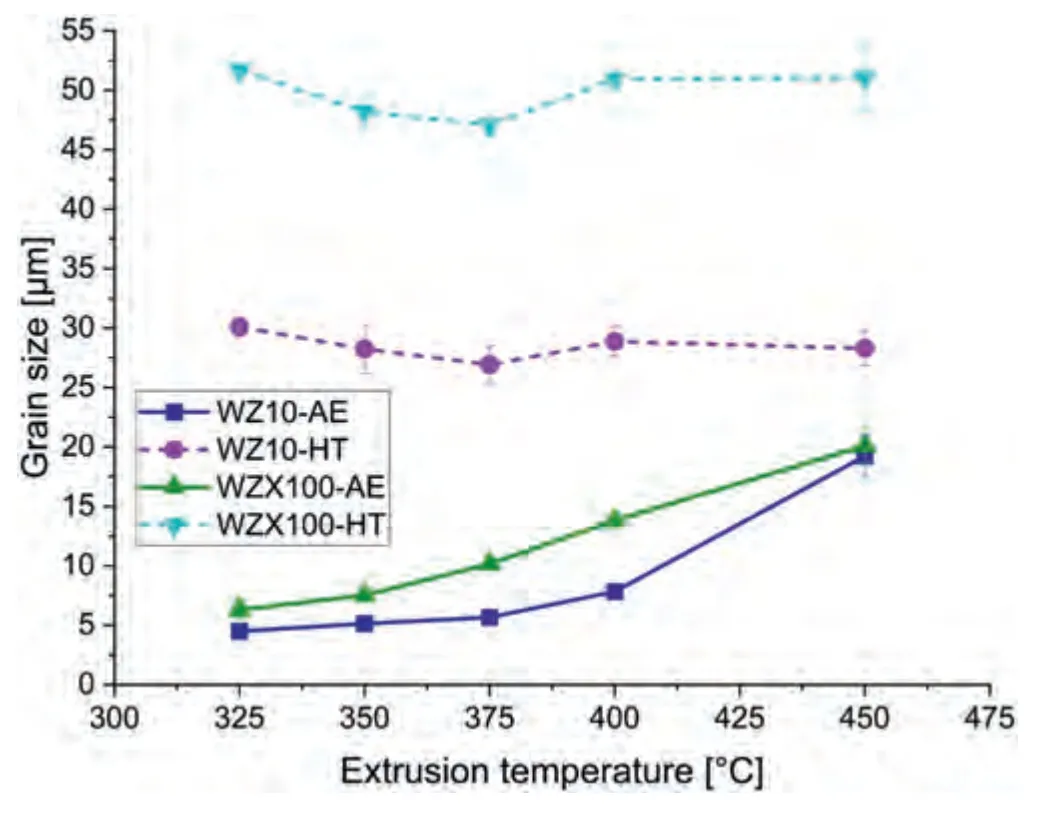

An influence of Ca on the dynamic as well as static recrystallization behavior can be clearly determined by the microstructure development during extrusion (AE) as well as by a subsequent heat treatment (HT),shown in Fig.2.The correlating grain size development as a function of the extrusion temperature of the as extruded condition (AE) as well as after heat treatment at 450 °C for 10 min (HT) are shown in Fig.3.

The WZ10 samples extruded at the temperature range of 325 °C and 375 °C show partially recrystallized microstructures with only a minor variation in grain size (4–6 μm).The microstructure exhibits a strongly deformed structure,to be identified by the elongated grains in the extrusion direction (ED),with fine-grained recrystallized areas around them.After the extrusion at 400 and 450 °C,fully recrystallized microstructure is developed with a significant increase in the average grain size to 8 and 19 μm,respectively.After heat treatment of the extruded profiles,a fully recrystallized microstructure with a comparable grain size of 29 ± 2 μm is obtained in all conditions(extrusion temperatures).In contrast to the WZ10,the WZX100 samples at the as-extruded condition show an almost linear increase of the average grain size from 6 to 20 μm as a function of the extrusion temperature.Only at the lowest temperatures (325–350 °C) a minor fraction of non-recrystallized grains were observed.Heat treatment results in pronounced grain growth (50 ± 2 μm).The above-mentioned results clearly show that the addition of Ca to the WZ10 alloy leads to the enhanced dynamic recrystallization during the extrusion and faster grain growth behavior during the subsequent annealing.

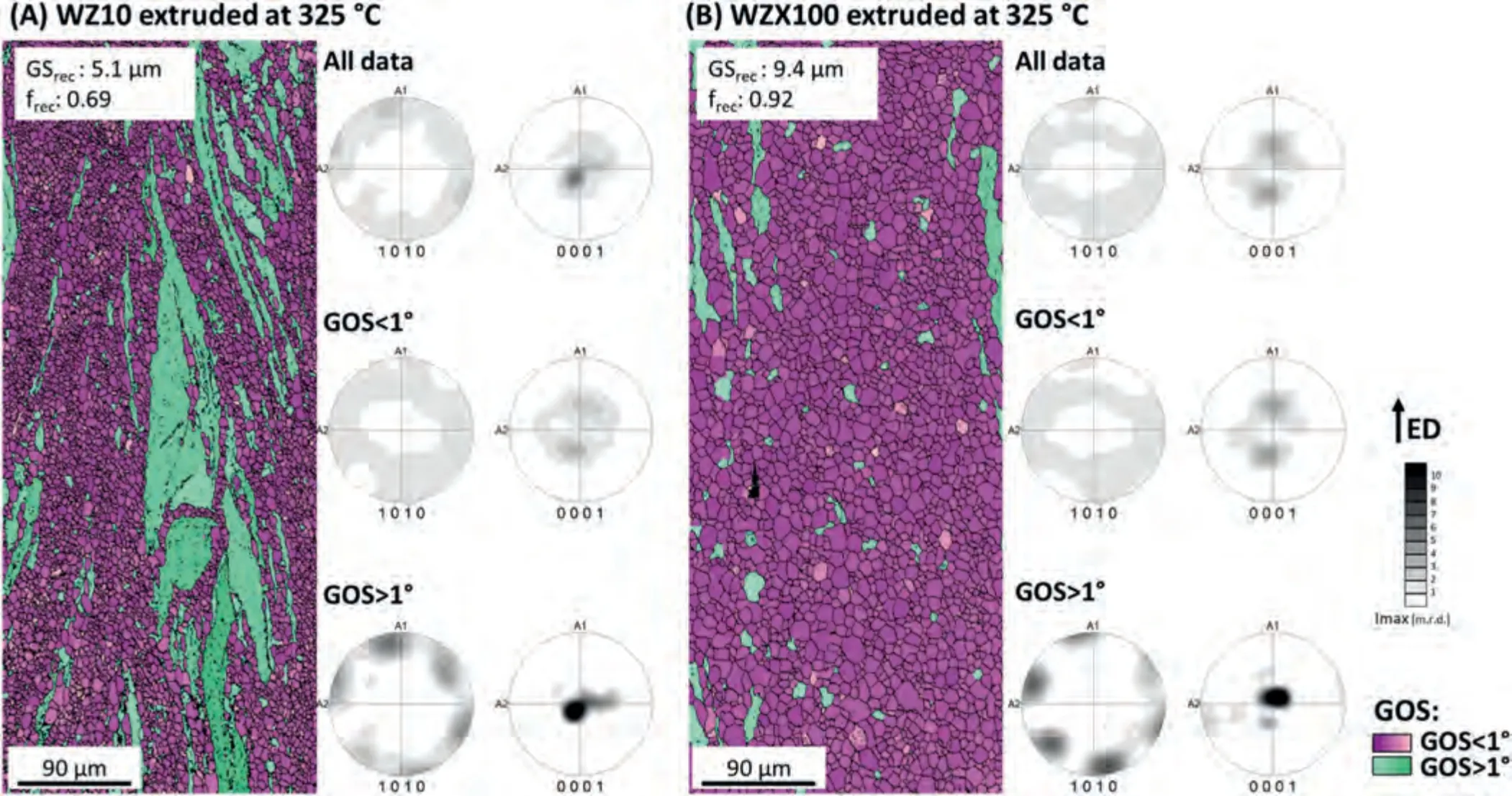

In order to examine the influence of Ca on the dynamic recrystallization behavior more in detail,it is worthwhile to consider the degree of recrystallization.For this purpose,EBSD measurements of WZ10 and WZX100 in the as extruded condition,extrusion temperature of 325 °C,were conducted and the results are shown in Fig.8.The microstructure fractions were classified by grain orientation spread (GOS).This approach applies a concept from other works [34,37,45],assuming that recrystallized grains exhibit a low intragranular misorientation,i.e.lower orientation variation within a grain.Grains with deformed state typically show a higher intragranular orientation spread.The grains with GOS>1° are marked in green color,which are assumed as non-recrystallized.The remaining fraction with the GOS<1° (purple) corresponds to the recrystallized grains.

The WZ10 alloy extruded at 325 °C shows a recrystallization fraction of 69%.It is known that Zn has an influence on the recrystallization behavior of Y or rare earth containing alloys.Segregations of Y and Zn at grain boundaries inhibit grain boundary mobility and retard grain growth and consequently recrystallization [19,46].In contrast,the WZX100 alloy extruded at 325 °C presents a mostly dynamically recrystallized microstructure with a fraction of recrystallized microstructure of 92%,i.e.accelerated DRX due to the Ca addition.

Fig.2.Micrographs from longitudinal sections (ED horizontal) of the extruded flat bands of WZ10 and WZX100 in the as extruded condition (AE) and after heat treatment (HT).

Considering the grain sizes of the as extruded materials(see Fig.3),no significant difference between both alloys extruded at 450°C is detected(around 30 μm).Therefore,it can be assumed that the addition of Ca accelerates the dynamic recrystallization,but has a limiting effect on grain growth during extrusion.This can be explained by the fact that Ca (Ca solutes) or Ca-containing secondary phases increase the nucleation rate during recrystallization and consequently leads to a faster DRX.It can be assumed that the DRXed grains limit each other’s growth and the size of the DRXed grains remains small.It has been shown in the literature [18,47]for various Zn and Ca containing Mg alloys (ZX) that a low Ca addition can lead to a formation of homogeneously distributed intermetallic Ca2Mg6Zn3.This phase accelerate DRX(higher nucleation rate)and inhibit grain growth by restricting the movement of grain boundaries (GBs).Consequently,Ca results in accelerated DRX with an increased number of recrystallization nuclei while inhibiting dynamic grain growth,which is consistent with the results of this study.In addition,regarding the extrusion forces at 325 °C (see Fig.1),a significant increase of the force could be observed for WZX100(1.99 MN) compared to WZ10 (1.76 MN).Higher extrusion force can also results in accelerated DRX due to increased adiabatic heating from deformation.

Fig.3.Average grain size (corresponding to Fig.2) as a function of the extrusion temperature (average grain size measured only on recrystallized grains) for as extruded (AE) and heat-treated (HT,450 °C for 10 min) bands.

In order to show the influence of Ca on static recrystallization/ grain growth,a subsequent heat treatment was used.The microstructure (Fig.2) and grain size development (Fig.3) of the heat-treated bands clearly indicate a difference between WZ10 and WZX100.Both alloys have a completely recrystallized microstructure due to the heat treatment (10 min at 450 °C).WZ10 has an average grain size of 29 ± 2 μm,independent of the extrusion speed.In contrast,the grain size of WZX100 is significantly larger with 50 ± 2 μm.It can be assumed that Ca in combination with Y and Zn accelerates the grain growth.Contrary to the results of the present study,many previous studies claim [15,17,35,48] that Ca addition retards SRX or acts as a grain refiner.However,it should also be noted that the results in the literature deal with Al-Zn-Ca-Mg and Zn-Ca-Mg alloys,not the alloys simultaneously containing Zn,Y and Ca.Hence,the addition of Ca to a Zn-Y-Mg alloy seems to have a contrary effect on the recrystallization and grain growth behavior.

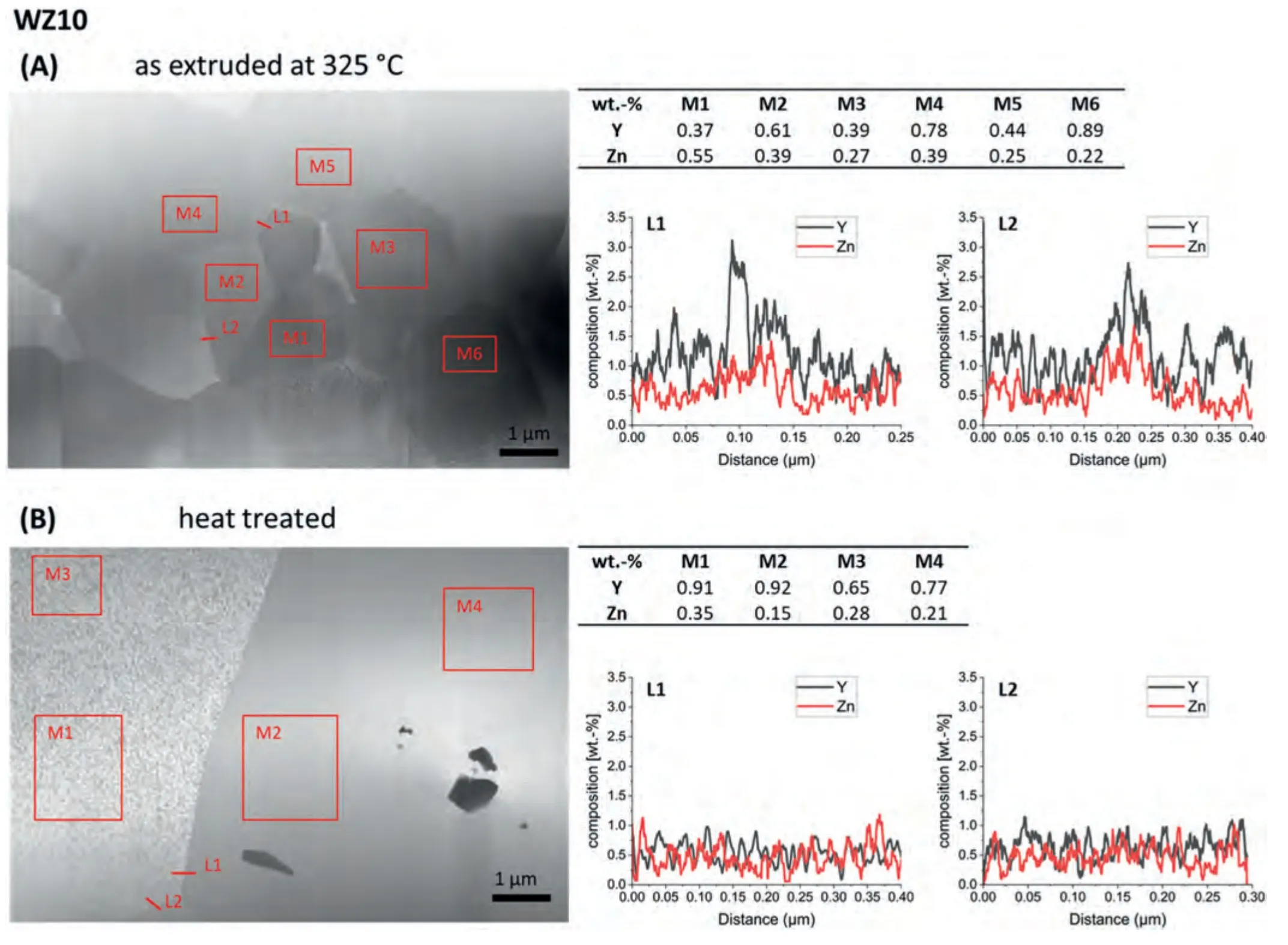

To investigate and understand the different grain growth behaviors between WZ10 and WZX100 alloys,elemental segregations at the grain boundaries were analyzed by scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) combined with EDX.The analysis shown in Figs.4 and 5,were carried out on the both alloys extruded at 325 °C,in the as-extruded condition and after heat treatment for 10 min at 450 °C.The element distribution over the grain boundaries was examined by line scans,marked with ‘L’.The areas marked with ‘M’indicate the measuring area of the concentration in the matrix.

The WZ10 alloy in the as-extruded condition (Fig.4(A))shows a higher concentration of Y and Zn segregations at the grain boundaries (L1,L2).The matrix measurements,M1 to M6,show a lower Y content of 0.37–0.89 wt% compared to the grain boundaries.

The subsequent heat treatment leads to a significant reduction of Y concentration at/near the grain boundaries (L1 and L2 in Fig.4(B)).The Y content in the matrix tends to increase (0.65–0.92 wt.%),with a large variation both in the as extruded condition and in the HT condition.The Zn content in the matrix does not show any major difference.

In comparison to WZ10,a contrary development is observed for WZX100 (Fig.5).The subsequent heat treatment results in a tendency reduction of the yttrium content in the matrix from 0.75-1.34 wt.% to 0.69–1.06 wt.%.Again,the scatter of the measurement results is very large.Zinc content does not show any real trend,it varies between 0.12 and 0.38 wt.%(as extruded)to 0.37–0.45 wt.%(heat treated).Furthermore,an influence of the heat treatment on the Ca content in the matrix is also not evident.At the grain boundaries of WZX100 in the as extruded condition an increased concentration of the solute atoms,Zn,Ca and Y can be observed (L1 and L2 in Fig.5(A)).The subsequent heat treatment results in a reduction of these elements at the grain boundaries (peak)(L1 and L2 in Fig.5(B)).In general,there seems to be an increase in yttrium near the grain boundary compared to the extruded state.It appears that there is a more homogeneous distribution of Y in WZX100 due to the heat treatment.

In the literature,it has been reported that RE elements[49,50] or yttrium additions [51] in magnesium alloys lead to the segregation near to the grain boundaries during the deformation process.This is also consistent with the presented results of both alloys (Figs.4 and 5),where high yttrium concentrations were found at the grain boundaries.Studies have shown [19,46] that the Y segregation along grain boundaries inhibits the mobility of dislocations and grain boundaries by the solute drag effect,thus inhibiting grain growth,resulting in a relatively small final grain size.With respect to a variation in grain size due to the addition of Ca,Guan et al.[38] described for a ZX10 alloy that the segregations (Ca and Zn) are not limited to specific types of grain boundaries (low or high angle grain boundaries).Hence,both alloying elements tend to retard recrystallization or grain growth due to the solute-and/or particle-drag effect.However,this does not match with the results of this work.Here,compared to WZ10 an accelerated grain growths was detected in the WZX100 alloy.

A reason for the enhanced grain growth of the WZX100 alloy during the annealing up to a grain size of 50 μm(WZ10 only∼30 μm)could be the disturbed diffusion of the Y atoms by the Ca atoms.Compared to WZ10,WZX100 generally shows a lower Y-content in the grain boundary near zone in the as extruded condition.Thus,the applied energy during deformation is not enough to accumulate sufficient yttrium at the grain boundaries.Consequently,the mobility of the grain boundaries is not completely inhibited by the solutedrag effect [46,50] or particle drag effect [52].

In addition,a displacement/suppression effect at the grain boundaries caused by Ca could be observed(Fig.5(A)in L2),which leads to the fact that yttrium atoms could not be segregated at certain grain boundaries.This can be explained by the fact that Ca has a higher diffusion rate than Y [53] and the yttrium atoms therefore require significantly more time and energy to distribute homogeneously.This is clearly shown with an increase of the Y content near the grain boundaries in the heat treated condition (Fig.5(B) in L1 and L2),compared to the as extrude condition.Furthermore,a significant homogenization (matrix similar to grain boundary) of the yttrium in the material only occurs during static recrystallization in WZX100.This means that the content in the matrix tends to decrease because of the heat treatment.Moreover,no major difference could be found in the Ca concentrations in the matrix between the initial and heat treated states.This additionally argues for the faster diffusion of Ca and the resulting delayed diffusion of yttrium atoms which results in the grain size difference due to the grain growth of WZ10 and WZX100.

Fig.4.STEM images of WZ10 in the extruded state (A) and heat treated state (B) with locations of the EDX scans as well as analyses of the matrix measurements;EDX line scan (wt.-%) over the gauge length.

3.2.Texture

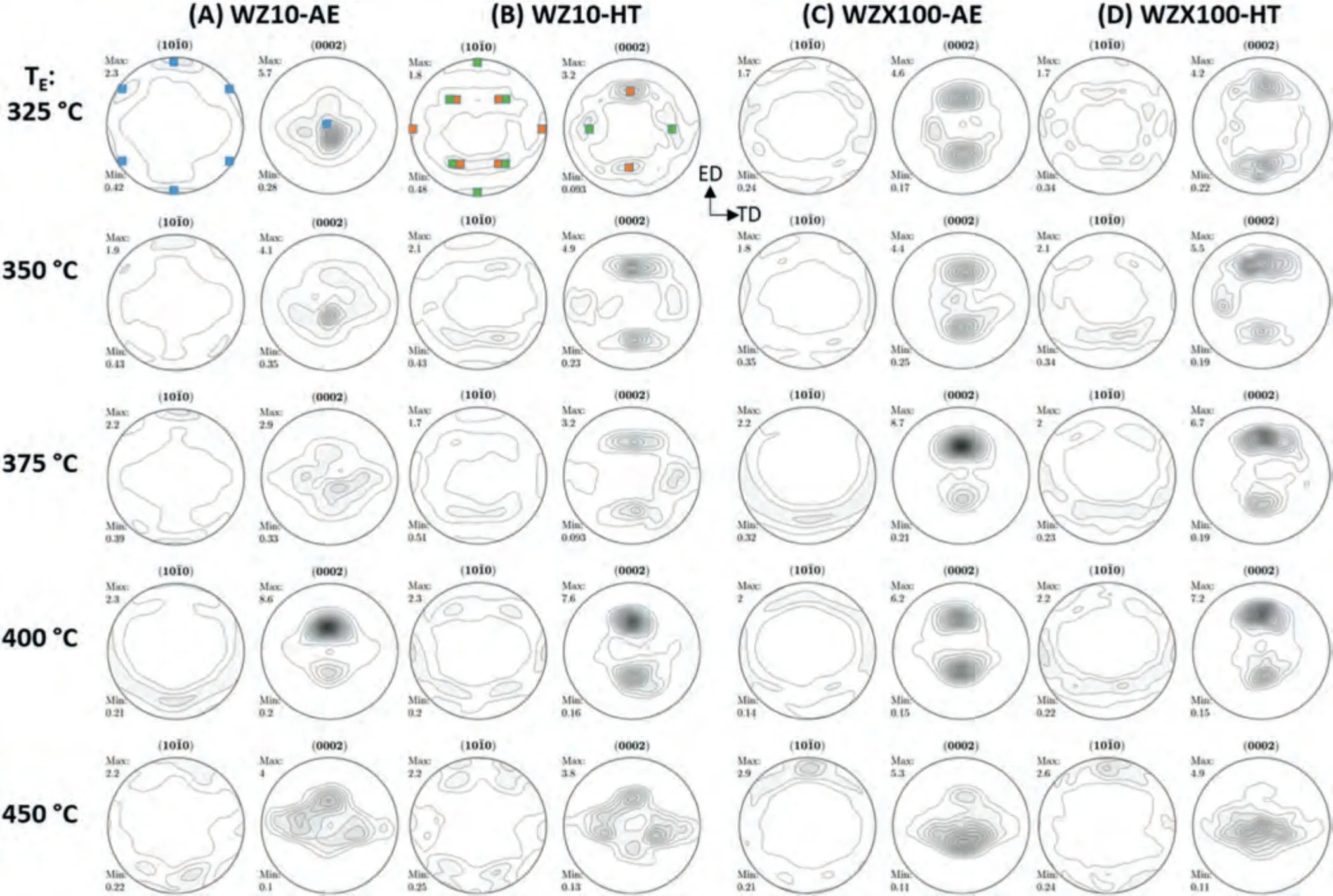

The global textures of the flat bands extruded at different temperatures are compiled in Fig.6.The (0002) pole figure of the WZ10 sample extruded at 325 °C (Fig.6(A)) shows a pronounced basal {0001}<10–10>component (highlighted in blue),in which the (0001) planes are laid parallel to the ND and 〈10–10〉 in the extrusion direction,with a maximum intensity of 5.7 m.r.d..Furthermore,the (0002) pole figure exhibits a broader angular distribution of the basal planes in± extrusion direction (ED) and ± transvers direction (TD).With increasing extrusion temperature up to 375 °C the max.intensity of the (0002) pole figure decreases and the tilt angle of the basal poles to the TD increases.The sample extruded at 400 °C shows a {0001}<10-10>component tilted by 30°in ± ED from normal direction (ND) with a strong texture strengthening (max.intensity 8.6 m.r.d.).Such texture with the double peaks in ED ((0002) pole figure) is typically observed in extruded flat products of Mg alloys containing RE elements [9,34,54].The asymmetrical intensity distribution of the double peak is not unknown.As Bohlen et al.[54,55]have already shown,extrusion of flat products more often results in a stronger intensity in the extrusion direction.The texture at high extrusion temperatures (450 °C) shows a clear texture weakening with a maximum intensity of 4.0 m.r.d..The basal {0001}<11-20>component is tilted only in ED and a higher distribution of basal planes is observed in TD.

The influence of the heat treatment on the texture of WZ10(Fig.6(B)) is particularly evident at low extrusion temperatures (325–375 °C).In this temperature range,the texture shows two components.A{0001}<11-20>component tilted by 45° from ND in ± ED (highlighted in orange) and a {11–20}<10-10>component tilted by 30° from ± TD toward ND (highlighted in green).These two components together(green and orange) form a kind of “quadrupole texture”.At 400 °C,the heat treatment results only in a more pronounced formation of the double peak in ED and a reduction of the intensity in the transverse direction.In the extruded condition at 450 °C,the HT has no effect on the texture component development.It is important to point out that the texture at 450 °C differs significantly from that at 325–375 °C in the heat-treated state.At first glance,the texture also looks like the quadrupole texture,but it differs significantly in the tilt angle of the components and in the homogeneous symmetry formation.

As already shown in the microstructure development,the texture development is also influenced by Ca,see Fig.6(C).In WZX100,at an extrusion temperature of 325°C,the strong basal texture is no longer visible compared to WZ10.Here,the typical RE texture component ({0001}<11-20>component tilted by∼30° in ± ED from normal direction (ND)) is already evident at low extrusion temperatures.With increasing extrusion temperature no influence on the texture component development can be detected up to a temperature of 400 °C.Same as for WZ10 at 400 °C,texture strengthening also occurs for the 375 °C sample.At 450 °C the RE component is no longer present and a pronounced basal texture with a tilt of the basal planes in the transverse direction is achieved.

Due to the following static recrystallization and grain growth,as a result of the heat treatment (see Fig.6(D)),in WZX100 the just described double peak remains in the texture and only the tilt angle of the component changes from 30°to about 45°at 325 °C and 350 °C.In addition,at 325 °C and 350 °C there is a slight formation of a transverse component (but not as distinct as with WZ10).

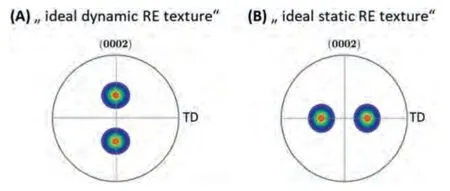

The results of the texture development in the as extruded state as a function of extrusion temperature both alloys show in correlation with microstructure development: If the microstructure is fully or almost fully dynamically recrystallized during the extrusion process,WZ10: 400 °C and WZX100:325–400 °C,a double peak in ED is visible,the so-called“rare-earth texture component”.Common examples of RE textures are the<11-21>// ED fiber formed during extrusion in circular profiles [35,56,57] and a double peak in ED({0001}<11-20>component tilted by 30°-45° from ND into ± ED) formed in extruded flat profiles [34,54,58,59].The RE component can also be identified during rolling.In this case,a double peak in TD ({10–10}<11-20>component tilted by 30° from TD into ND) [29,37,60,61] is formed not during the process but as a result of the subsequent heat treatment(SRX).In comparison,the RE-texture component in extrusion is already formed by the process (DRX) and cannot be significantly changed by a subsequent annealing.These two different recrystallization-dependent RE components (dynamic and static) calculated with MTEX are represented in Fig.7.

Fig.6.Pole figures (ED vertical) of the extruded flat bands of WZ10 and WZX100 in the as extruded condition (AE) and after heat treatment (HT);Main texture components highlighted.

Fig.7.Ideal RE-texture components calculated with MTEX.

Concerning the “dynamic RE texture,” Barnett et al.[62] (for ME21) and Bohlen et al.[56] (for different Mg-Mn-RE alloys) confirm that the recrystallized part of the microstructure always shows a RE component<11-21>//ED("dynamic RE texture") during extrusion.The microstructure(Fig.2)and the texture results(Fig.6)show that static recrystallization and grain growth (additional heat treatment) have no influence on the development of texture component if the dynamic RE texture component is already formed during extrusion,i.e.by dynamic recrystallization.Only a weakening of the texture intensity due to grain growth can occur.

At high temperatures (450 °C),in addition to the broadening of the distribution of basal planes in TD,an intensity maximum with tilt to ED is formed,whereby the resulting tilt angle depends on the alloy.The broadening of the distribution of basal planes in TD with increasing temperature has been observed in previous work for AZ31[11].Furthermore,Imandoust et al.[63] and Tang et al.[64] attributed the formation of the transvers component to higher activity of prismatic slip.The absence of the RE texture and the presence of a maximum in ED can be associated with a missing solute drag effect.It can be assumed that at temperatures above 450 °C rare earth elements or Y and Zn miss their effect on texture development and a limitation of grain boundary mobility by these elements (solute drag) is no longer significant,so that other mechanisms determine texture development [65].

If the thermal input required for complete dynamic recrystallization is too low,partially recrystallized microstructures will be formed during extrusion.In this case subsequent static recrystallization allows the formation of a quadrupole texture.The quadrupole texture is clearly visible in WZ10(325–375 °C) and weakly pronounced in WZX100 (325–350 °C),Fig.6.This means that the dynamically recrystallized RE component (double peak in ED,see Fig.7(A))formed during the process remains and a static RE component (double peak in TD,see Fig.7(B)),which is already known from rolling [37,54],is additionally formed as a result of the heat treatment (SRX).Consequently,the formation of this quadrupole texture can be justified by the presence of a non-recrystallized microstructure fraction after the extrusion process.

Fig.8.Alloy-dependent microstructure and corresponding textures evolution for(A)WZ10 and(B)WZX100 extruded at 325°C;subdivision of microstructural fractions into GOS>1° (deformed microstructure) and GOS<1° (dynamically recrystallized microstructure) green: deformed microstructure GOS>1°;purple:recrystallized microstructure GOS<1°.

Due to the different RX behavior caused by the addition of Ca to WZ10,it also seems to be the reason why WZX100 does not form such a pronounced quadrupole texture at low extrusion temperatures as WZ10 does by subsequent heat treatment.Instead,WZX100 predominantly exhibits (up to 450 °C) the typical dynamic RE texture that forms in the process and represents a fully DRX microstructure.

The influence of Ca on the degree of recrystallization(DRX) has already been discussed in the previous part ‘Microstructure’.In order to analyze the texture components from different microstructural fractions (mainly dynamic recrystallized and unrecrystallized),EBSD measurements (Fig.8) of WZ10 and WZX100 extruded at 325 °C are executed.In both alloys the dynamic RE-texture component (double peak in ED) dominates in the dynamically recrystallized microstructure fraction (GOS<1°).A very small amount of transverse broadening can also be seen.It should be noted that DRX dominates the extrusion,but SRX also occurs.Thus,it is natural that a small amount of the static RE-texture can also develop during the extrusion process.

Since the degree of recrystallization is already this far in WZX100,the dynamic RE texture also outweighs the entire texture(All Data).Against this,WZ10 shows a different component dominating the entire texture.Considering the texture of the non-recrystallized microstructure fraction (GOS>1°),it can be seen that the orientation is similar to that of the entire texture of WZ10.WZX100 also shows this basal{0001}<10–10>component in the small amount of deformed microstructure.

This deformation component(typical for non-recrystallized“deformed” microstructure) can also appear as a prismatic{11–20} component tilted 60° from TD in ND [34].The deformation component is alloy-independent and is characterized in extruded round profiles by a strong prismatic fiber or in flat profiles with high intensity in the (1010)-pole figure along the ED [27,35,66–68].

The origin of this deformation texture component demands an effect of different deformation mechanisms.It has been shown for rolled sheets that preferential prismatic slip instead of basal slip is consistent with such effects [69].Jiang et al.[68] proved for extruded round profiles that prismatic-slip is also the main effect.They showed that subgrains are continuously created in the dynamically recrystallized grains with (10–10) fiber orientation,which are mainly formed by the rearrangement of prismatic-slip dislocations and gradually transformed into new DRX grains.In addition to the discussed slip systems that contribute to the texture change,it can be assumed that the texture component,{11–20}<10-10>tilted by 30° from ± TD in the ND direction,is also created by compression twins [70,71].

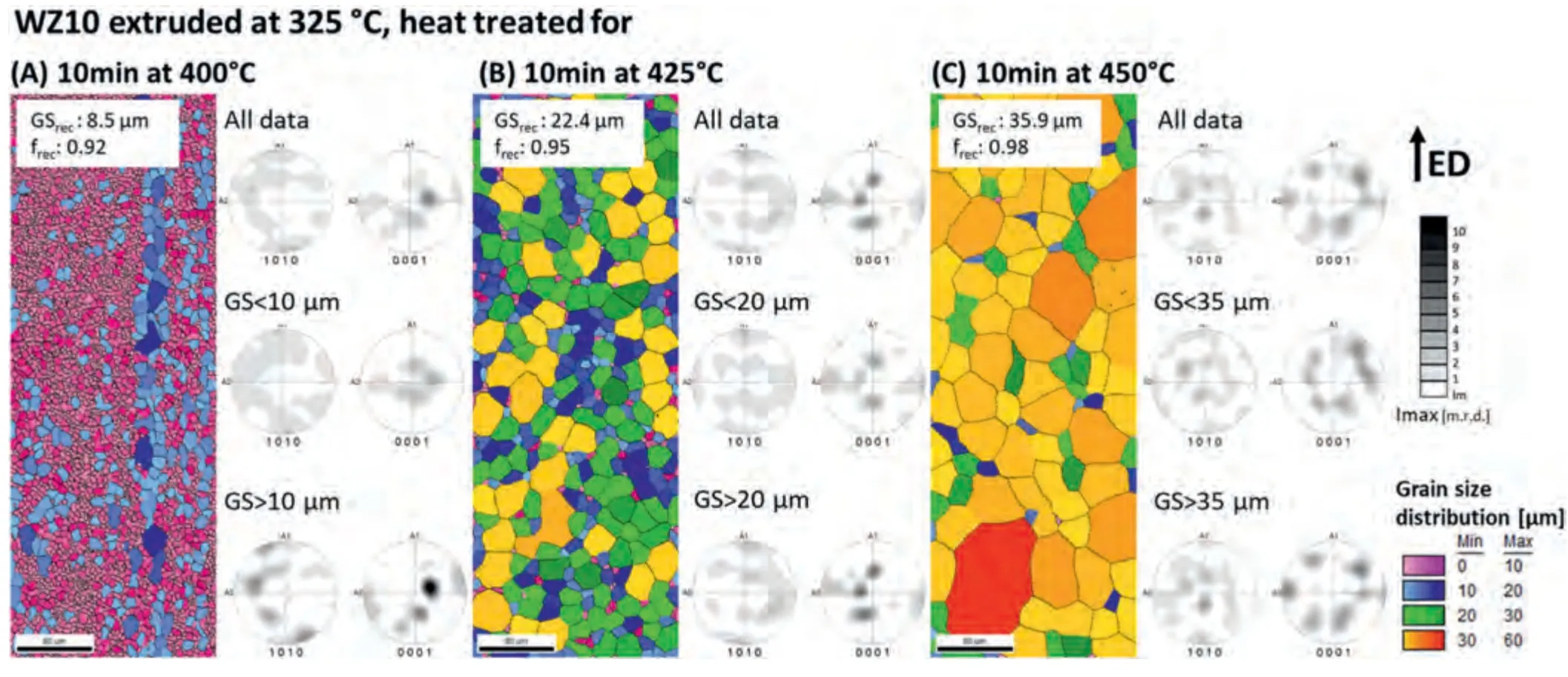

Fig.9.Grain size dependent subdivision of EBSD measurements and corresponding textures for WZ10 extruded at 325 °C after heat treatments at (A) 400 °C,(B) 425 °C and (C) 450 °C for 10 min.

Based on the findings from the microstructures as well as textures,it can be assumed that a partially recrystallized microstructure is required as an initial microstructure to form the transverse component by the static recrystallization (heat treatment).As the degree of recrystallization in WZX100 is very advanced,the non-recrystallized microstructure fraction is insufficient to produce a pronounced quadrupole texture by static recrystallization and grain growth.

In order to demonstrate the evolution of the quadrupole texture and prove that it depends on the initial microstructure,the WZ10 alloy extruded at 325 °C is annealed at 400 °C,425 °C and 450 °C each for 10 min.The results are discussed in terms of grain size dependent subdivision EBSD measurements in Fig.9.After annealing for 10 min at 400 °C(Fig.9(A)),the almost completely recrystallized microstructure (92%) with an average grain size of 9 μm presents a bimodal grain structure and grain growth (initial grain size:5.1 μm,Fig.8)takes place only to a limited extent.The overall (0002)-pole figure (All data) reveals a quadrupole texture,whereby the tilt angle of the quadrupole texture components,being lower than in the annealed state at 450 °C (Fig.9(C)).It can be clearly seen that larger grains (GS>10 μm) are lamellar oriented in the direction of extrusion.Based on the morphology,it can be assumed that these large grains are new statically recrystallized grains from the non-recrystallized grain fraction,as can be seen in the initial state in Fig.8(A).Due to the high dislocation density of non-recrystallized areas,it is understandable that these areas recrystallized statically first.

In addition,small grains below 10 μm show almost no change in the texture to the initial material.The dynamic RE texture is pronounced and,moreover,a broadening of basal planes in the transverse direction is slightly more pronounced(compared to the initial material).

As the grain size increases,the intensity of the transverse component becomes more significant and the RE component becomes less pronounced.Consequently,the transverse component arises from the non-recrystallized grains (bands) that are present in the extruded initial microstructure (Fig.8(A),green highlighted microstructure).

This also becomes clear by considering the heat treated condition at 425 °C (Fig.9(B)).Grain growth is now occurring (GS: 25 μm).The fraction of non-recrystallized microstructure with 5% is negligible.It can be seen that with increasing grain size the intensity of the transverse component increases,but the tilt angle does not change.Only with increasing grain growth,i.e.after annealing at 450 °C(Fig.9(C)),an increase in the tilt angles of both components can be observed.The average grain size is now around 35 μm.Primarily the RE component is represented in the grains smaller than 35 μm,while a prismatic component is very dominant in the grains larger than 35 μm.Also,Imandoust et al.[63] and Barrett et al.[72] showed that static recrystallization and its nucleation/grain growth contribute to the disorientation of the texture and justified this with RE segregations at grain boundaries,which could alter the effective grain boundary energy and mobility variations between grain boundary types.

These results strengthen the assumption that the quadrupole texture is formed from a combination of dynamic and static recrystallization RE textures (see Fig.7).It is proven that a not fully recrystallized microstructure is required for the formation of the transverse component (static RE-component),and that grain growth plays a key role in determining the final texture.Grain growth is the cause of the significant increase in the tilt angles of the RE components.Consequently,it is meaningful that the quadrupole texture does not form in the case of WZX100 due to the subsequent heat treatment,since here the DRX progresses too fast during the extrusion process and so the proportion of non-recrystallized microstructure is too small.

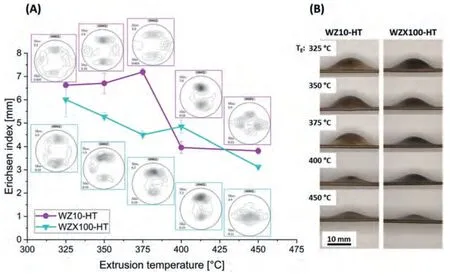

Fig.10.(A) Erichsen index depending on the extrusion temperature for WZ10 and WZX100 in the heat-treated condition with the corresponding basal (0002)pole figure;(B) Side morphology of the cupped samples.

3.3.Formability

Fig.10(A) presents the Erichsen index of the heat treated WZ10 and WZX100 bands extruded at different temperatures with the corresponding basal (0002) pole figure and in Fig.10(B) shows the corresponding samples after Erichsen test.An Erichsen value of 6.6 mm to 7.2 mm was measured for WZ10 bands extruded at 325 °C,350 °C and 375 °C.The bands extruded at 400 °C and 450 °C show a largely reduced Erichsen values of approximately 4 mm.The WZX100 bands display a continuous decrease of the Erichsen index with increasing the extrusion temperature,except the band extruded at 400 °C.A high Erichsen index of 6.0 mm was achieved after the extrusion at 325 °C,while the Erichsen value decreases drastically to 3.1 mm after the extrusion at 450 °C.The addition of Ca to WZ10 significantly limits the extrusion process parameters,in which a high Erichsen value (min.of 6 mm)can be achieved(only at 325°C).The restriction of the formability of WZX100 can be correlated with the changed DRX as well as SRX recrystallization behavior by alloying Ca to WZ10 and the thus a changed texture development.The dependence of formability on the texture will be explored in the following.

The formability at room temperature depends on the activity of the deformation mechanisms,e.g.CRSS,and the texture,i.e.the orientation and distribution of the respective lattice planes.It is reasonable to focus on the geometrical influence on the activation of the basal slip with the lowest critical resolved shear stress (CRSS),i.e.Schmid’s shear stress law with respect to the texture.For the biaxial stretch forming,like Erichsen test,a weak texture with symmetric distribution of the basal poles broadly tilted from the ND(quadrupole texture) is ideal for basal slip [22–24,26,34].

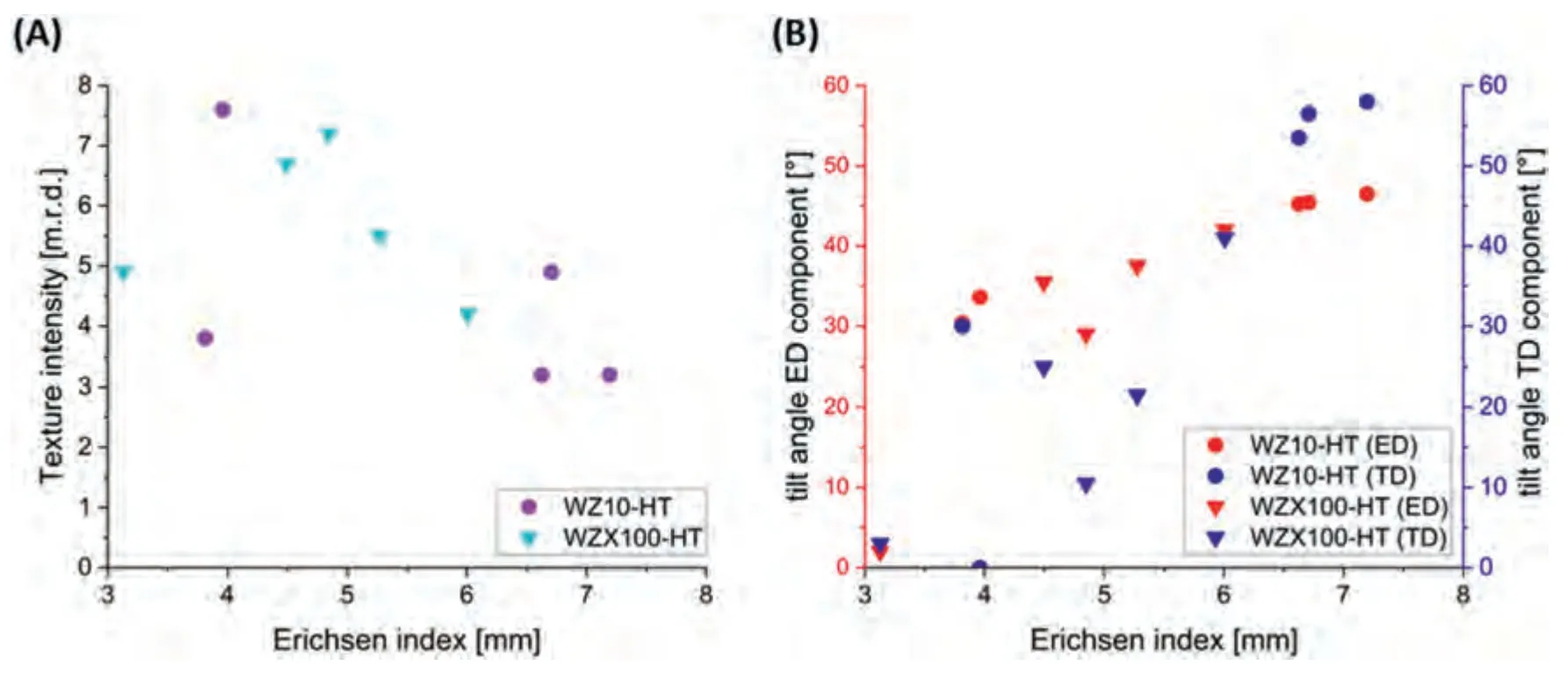

As previously mentioned,texture intensity seems to be a major factor affecting biaxial formability.Therefore,in Fig.11(A) the texture intensity of the (0002) pole figure is plotted against the Erichsen index.But for both alloys,the expected behavior is not observed (only a small correlation),a decrease of the texture intensity resulting in an increase of the Erichsen value.

Apart of the texture intensity,the tilt angle of the basal planes of the (0002) pole figure (Schmid’s shear stress law)has an influence on the formability.The analysis of the influence of the tilt angle of basal planes in ED (red symbols) and TD (blue symbols) shows a more evident linear relationship with the Erichsen value,as shown in Fig.11(B).Particularly for the tilt of the basal planes in ED,it shows that a higher tilt angle results in a higher biaxial formability.A similar(but not quite as severe) development can be seen for the tilt in TD.Considering both tilt angles,it is clear that for both TD and ED,a tilt angle of min.40° is required to achieve an Erichsen value higher than 6 mm.This also explains the low Erichsen value of WZ10 extruded at 450 °C,despite the texture components in ED and TD,the tilt angle is too low.Since a high tilt angle leads to a reduction in the difference in CRSS between basal and non-basal slip systems,resulting in more material flowing out of the sheet plane and an increase in ductility [24].

It should be noted that the extruded heat-treated WZX100 bands can only be deformed well at a process temperature of 325 °C.The Erichsen value decreases significantly above 350 °C.This behavior is related to the texture,since the quadrupole texture,or a high tilt angle of the basal planes,can no longer be formed at temperatures above 325 °C due to the subsequent heat treatment.The reason for this has already been given by the accelerating effect of Ca on the DRX.For WZ10,on the other hand,a partially recrystallized microstructure can be extruded in a temperature range of 325 °C-375 °C and thus the quadrupole texture and a high tilt angle can be adjusted by subsequent heat treatment (SRX).The improved formability can be understood as a result of the texture weakening,increased tilt angle and the accompanying development of the non-basal type texture.

Fig.11.Erichsen index depending on (A) the texture intensity of the (0002) pole figure and (B) the tilt angle of the basal pole from the ND towards the ED(red) and TD (blue).

4.Conclusions

Direct extrusion of flat bands has been used to study alloying and processing effects on the microstructure and texture development.The focus was on understanding the influence of both static and dynamic recrystallization on the microstructure and texture development and consequently the resulting biaxial formability at room temperature of the flat products.It is shown that alloying elements can have different effects depending on the recrystallization mechanisms (DRX,SRX).Using WZ10,it was shown that a partially recrystallized microstructure is necessary to form the quadrupole texture and a high tilt angle of basal planes by a subsequent SRX,which stands for high formability.The comprehensive study of the alloy influence presented here shows that Ca is not suitable as an alloying element for WZ10 alloy in terms of improving the semi-finished product properties at room temperature.This is due to the fact that during extrusion,the addition of Ca leads to an increased nucleation rate and consequently to a faster DRX.On the other hand,dynamic grain growth is inhibited by the nuclei.The acceleration of the DRX by Ca makes it impossible to extrude a partially recrystallized microstructure,which is necessary to develop the quadrupole texture by the subsequent SRX.Additionally,the SRX,or heat treatment,results in accelerated grain growth.This is due to the absence of Y at the grain boundaries and the associated lack of solute drag effect.

Data availability statement

The original data of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Prof.Karl Ulrich Kainer is an editorial board member/editor-in-chief for Journal of Magnesium and Alloys and was not involved in the editorial review or the decision to publish this article.All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maria Nienaber:Conceptualization,Methodology,Formal analysis,Investigation,Writing– original draft,Writing– review &editing.Jan Bohlen:Conceptualization,Methodology,Writing– review &editing.Sangbong Yi:Writing–review &editing.Gerrit Kurz:Writing– review &editing.Karl Ulrich Kainer:Supervision,Validation,Writing– review &editing.Dietmar Letzig:Conceptualization,Methodology,Supervision,Validation,Writing– review &editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr.Günther Meister and Mr.Alexander Reichart for their help during casting and machining of the billets.We also appreciate the great support of Ms.Victoria Kurz for preparation of the microstructures.

杂志排行

Journal of Magnesium and Alloys的其它文章

- Magnesium and its alloys for better future

——The 10th anniversary of journal of magnesium and alloys - Magnesium alloys in tumor treatment: Current research status,challenges and future prospects

- Twin-solute,twin-dislocation and twin-twin interactions in magnesium

- Recent advances on grain refinement of magnesium rare-earth alloys during the whole casting processes: A review

- Magnesium research in Canada: Highlights of the last two decades

- Structure-function integrated magnesium alloys and their composites