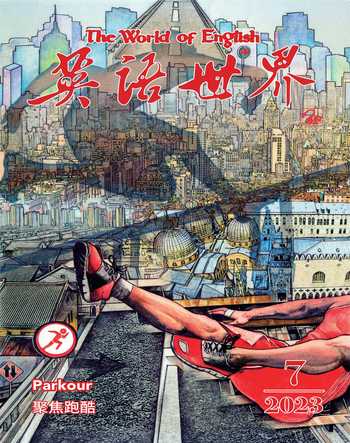

Parkour: China as a Playground跑酷:把中国当作游乐场

2023-07-22玛丽安娜·切里尼李方超/译

玛丽安娜·切里尼 李方超/译

Urban sports are having a moment. Walk through a park in most big cities today and youll easily see kids riding a skateboard, rollerblading or doing some freestyle running. China is no exception. The country has witnessed a surging popularity of “extreme” expressions of athleticism that use the city as their playground. Although still far from being mainstream.

城市运动当下正风靡。如今,你若在大多数大城市的公园里漫步,儿童玩滑板、滑旱冰,或是随性奔跑的画面随处可见。中国也不例外。运动才能的“极限”表达是把整座城市当作游乐场,这种表达方式在中国迅猛流行起来,尽管远未成为主流。

“Parkour feels like flying. To me, it represents freedom.”

“跑酷就像飞一样。对我来说,它代表自由。”

The discipline grew through young Chinese athletes exposure to films. “Most Chinese traceurs learned about parkour through movies,” explains Ma, a former parkour practitioner in Beijing. “Thats how we were first exposed to it. Until, of course, it physically arrived in China.” The disciplines entrance into China dates back to 2006, when a few individuals decided to bring those free-spirited stunts from screen to reality, and started practicing as traceurs in parks and urban compounds.

這项运动在中国的兴起源于年轻一代运动爱好者接触到相关电影。“大多数中国跑酷者都是通过电影了解跑酷的。”生活在北京的前跑酷玩家马先生解释道,“我们正是以这样的方式首次接触到跑酷。当然,后来中国真的有人练起了跑酷。”这项运动进入中国的时间可追溯至2006年,当时有几个人决定把那些不受拘束的特技动作从银幕上搬到现实中,他们开始以跑酷者的身份在各大公园和城市建筑群中练习。

“Jumping off buildings wasnt exactly well received by people at first.”

“从建筑物上往下跳,人们一开始的确不太能接受。”

In China, of course, back-flipping and gravity-defying jumps were nothing too out of the ordinary: flailing, spinning heroes pour out of kung fu and wu xia tales that are the fixture of many a Chinese television series. Yet parkour had a difficult time taking off. “No one really knew what it was,” says Matt Talbot-Turner, co-founder of parkour magazine, BreathePK. “Jumping off buildings wasnt exactly well received by people at first, in China more than other places.” Undeterred by public perception, the first generation of Chinese traceurs continued practicing, and the sport grew quickly—albeit remaining niche.

当然,在中国,后空翻和反重力跳跃并不是特别稀奇的事情:功夫和武侠故事是中国电视连续剧的常设主题。这类电视剧很多,拳打脚踢、纵身腾空的主人公层出不穷。然而,跑酷曾经起步艰难。“没有人知道跑酷到底是什么。”跑酷杂志BreathePK的联合创刊人马特·塔尔博特-特纳说道,“从建筑物上往下跳,人们一开始的确不太能接受,中国的接受度比其他国家更低。”中国第一代跑酷者未受公众看法的影响,他们持续训练,于是这项运动迅速发展起来——尽管依然属于小众运动项目。

Soon enough, the word parkour was being translated as paoku (literally “cool running”) and drawing a growing number of athletes. By 2007, parkour routines1 were being posted on Tudou and Youku, while clubs were popping up like mushrooms across the nation. Talbot-Turner, who was in Shenyang between 2010 and 2012 fostering the discipline, says its growth was “phenomenal.”

很快,parkour这个词被译为“跑酷”(字面义是“炫酷奔跑”),并吸引了越来越多的运动爱好者。到2007年,一套套跑酷动作不断发布在土豆网和优酷网上。与此同时,跑酷俱乐部也在中国遍地开花。2010年至2012年,塔尔博特-特纳在沈阳推广这项运动,他称跑酷在中国的发展是“现象级的”。

A handful of keen devotees in China have even made the sport their full-time profession. Martino Chen, founder of Shanghai Parkour Community and Link Parkour, the first gym in Shanghai solely dedicated to the discipline, is one of them. He fell for the sport in 2008, after watching District 13, a film notable for its depiction of parkour in a number of stunt sequences that were completed without the use of wires or special effects. Like many other Chinese traceurs, he had no idea that the visually stunning acts in the movie were part of an internationally practiced sport. “I was just fascinated by the way people were jumping and flying over walls,” he recalls. A white-collar worker at the time, Chen started having a go at a few moves on his own. In time, he mastered the sport, becoming one of Chinas most prominent practitioners, and decided to make parkour his life pursuit. He quit his job and opened Link, aiming to teach parkour professionally in a safe environment.

中國个别跑酷狂热爱好者甚至已经把这项运动当作他们的全职工作,马蒂诺·陈就是其中一个。他成立了上海跑酷社群,还创办了上海第一家专门致力于跑酷的训练馆“Link跑酷”。2008年,陈先生看完电影《暴力街区13》后就爱上了跑酷。这部电影因大量的跑酷特技镜头而著称,而这一系列镜头的拍摄并未依赖威亚或是特效。与其他众多中国跑酷者一样,当时的陈先生并不知道片中极具视觉冲击力的表演竟是世界各地有人在练习的一项运动。他回忆称:“我当时被片中人物飞檐走壁的方式吸引住了。”于是,当时身为白领的陈先生开始自己尝试训练几个动作。一段时间后,他精通了这项运动,成为中国最有名的跑酷玩家之一,并决定把跑酷当作自己毕生的追求。他辞掉工作,创办Link跑酷训练馆, 目的就是在安全的环境中以专业的方式传授跑酷技能。

“Its amazing what parkour can make you do.”

“跑酷让你铸就不可思议。”

Despite worries of its dangers, one reason for the growing popularity of parkour in China, Chen says, is its accessibility to athletes at all levels. Its not necessarily a competitive sport: rather, its about progress at a level thats meaningful for you.

陈先生表示,尽管人们担心跑酷危险,但这项运动在中国日益受欢迎的一个原因就是各个水平的运动爱好者都可以参与。跑酷不一定要和别人竞技,而是在自己的水平上持续突破。

Ma in Beijing agrees: “Parkour is a very personal sport. Its about setting your own goals, both mentally and physically. The resulting sense of achievement is just great.” Indeed, actually jumping off something tall takes not just strength and technique but also mental discipline: You have to be willing to face your fears and commit to movements, trusting your bodys ability to take you where you want to go.

生活在北京的马先生同样认为:“跑酷是一项非常个性化的运动,自己给自己定目标,包括心理目标和体能目标。实现目标后会有非常大的成就感。”实际上,真的从高处往下跳需要的不只是力量和技巧,还有心理素质训练:你必须愿意直面自己的恐惧,专注于每一个动作,相信自己的身体有能力带你前往心之所向。

“Its amazing what parkour can make you do,” says Chen. “Although safety is obviously a very important issue. As a traceur, you must learn and always be aware of your limits.” Yang, a professional traceur and coach who trains alongside Chen in Shanghai, has learned that lesson the hard way. As he performed a flip he had done many times before, he failed to notice a wet patch on the ground. As he landed, his knee ligament tore. Yang had a long recovery, but eventually bounced back.

“跑酷让你铸就不可思议。”陈先生说道,“但安全显然是重中之重。当一名跑酷者,你必须学习,并且时刻要知道自己的极限。”杨先生以惨痛的教训明白了这个道理。他本身是职业跑酷者,也是专业跑酷教练,和陈先生一起在上海训练。他在做一个自己完成过很多次的空翻时,未注意到地面上有一块湿滑区域。他一落地,膝盖韧带就撕裂了。他花了很长时间康复,最终得以重拾活力。

“Parkour goes over walls, not around them; it takes the stair rail, not the stairs.”

“跑酷是越墙跑,而不是绕墙跑;跑上楼梯扶手,而不是走楼梯。”

“I love the sport so much that an injury is not going to stop me.” His biggest regret about the accident is having missed a training tour of Europe with his Shanghai parkour crew. “I would have loved to go and learn from our foreign counterparts,” he says. “China has come to parkour pretty late, so theres so much we have to improve on. We are growing but are still at a very rough, early stage of our potential.” Chen agrees. “Compared to the West, theres some lagging in terms of practice here, which may be one of the main challenges facing the development of parkour in the country.”

“我酷爱这项运动,一次受伤无法阻挡我。”对于这次意外受伤,杨先生最大的遗憾是他错失了机会,没能和上海的跑酷队友一起前往欧洲训练。“我本来很想去的,非常希望向外国同行学习。”他说,“中国跑酷的起步相当晚,所以有很多我们必须改进的地方。我们在发展,但是目前尚处于非常艰难的早期阶段,潜能有待开发。”陈先生表示认同:“相比西方国家,我们的训练方式有点落后,这也许是我国跑酷运动发展面临的一大挑战。”

The fact that most people still look down on the sport is another factor hindering its development—both Chen and Yang say their parents are not supportive of what they do, and would be happier if they had “real” jobs.

大多數人仍然瞧不上跑酷,这个事实是制约其发展的另一个因素——陈先生和杨先生都表示父母不支持他们从事跑酷,更乐意看到他们有一份“正经”工作。

Government backing of the discip-line—only if and when practiced safely—has seen the rise of a few parkour facilities in metropolises like Beijing and Shanghai. Although the city itself is a traceurs playground, offering spaces to train without potential safety hazards no doubt allows for a less-intimidating approach to the sport. “The sport is a social media darling,” says Talbot-Turner. “It prospers on the Internet like few other disciplines do. China being at the center of todays digital revolution makes it the perfect place for it to thrive.”

中国政府支持这项运动,但前提是必须安全进行,因此像北京和上海等大都市建起了少量跑酷运动设施。尽管城市本身就是跑酷者的游乐场,但是提供无潜在安全隐患的训练场所无疑能让跑酷变得不那么令人望而却步。“这项运动是社交媒体的宠儿。”塔尔博特-特纳说道,“很少有运动像跑酷这样在互联网上蓬勃发展。中国处于当今数字革命的中心,这一地位使其成为跑酷蔚然成风的绝佳场所。”

Ma likes to highlight another main aspect for which, he says, the sport is set to win more acolytes among the younger generation. “At its roots, parkour is as much about helping others to achieve things as it is about achieving things yourself,” he says. “And I think thats enticing for a lot of young people these days.” Parkour, like kung fu and other Chinese traditions, is as much about the philosophical as the phys-ical—and that may be one major reason to be optimistic about its chances in China. “Parkour feels like flying,” says Chen. “To me, it represents freedom.”

马先生想强调跑酷的另一大特色,他认为这个特色是跑酷定会吸引更多年轻人投入其中的原因。“说到底,跑酷的目的既是成就自我,也是帮助别人有所成就。”他说,“我认为这一点对如今很多年轻人而言很有吸引力。”跑酷和功夫等中国传统一样,不仅讲究健身,也关乎哲学——这可能是人们认为跑酷在中国前景乐观的一个主要原因。“跑酷就像飞一样。”陈先生说道,“对我来说,它代表自由。”

(译者为“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛获奖者;单位:四川民族学院)