Fatty liver and celiac disease: Why worry?

2023-05-30JanainaLuzNarcisoSchiavonLeonardoLuccaSchiavon

Janaina Luz Narciso-Schiavon, Leonardo Lucca Schiavon

Janaina Luz Narciso-Schiavon, Leonardo Lucca Schiavon, Department of Internal Medicine,Gastroenterology Division, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis 88040-900,Santa Catarina, Brazil

Abstract Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory intestinal disorder mediated by the ingestion of gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. Liver involvement in CD has been widely described, and active screening for CD is recommended in patients with liver diseases, particularly in those with autoimmune disorders,fatty liver in the absence of metabolic syndrome, noncirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension, cryptogenic cirrhosis, and in the context of liver transplantation.Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is estimated to affect approximately 25% of the world’s adult population and is the world’s leading cause of chronic liver disease.In view of both diseases’ global significance, and to their correlation, this study reviews the available literature on fatty liver and CD and verifies particularities of the clinical setting.

Key Words: Fatty liver; Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; Celiac disease; Transaminases;Aspartate aminotransferase; Alanine aminotransferase

INTRODUCTION

Celiac disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory intestinal disorder mediated by the ingestion of gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. It is relatively common and affects 0.7%–1.4% of the global population[1]. Its diagnosis relies on a combination of serologic testing for anti-tissue transglutaminase,anti-endomysial, and/or anti-deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies, as well as typical findings of villous atrophy and intraepithelial lymphocytosis in duodenal biopsies[2]. The classical clinical manifestations of CD, related to the gastrointestinal tract, are seen in 50%-60% of all cases. Non-classical CD accounts for 40%-50%, and is characterized by systemic involvement including musculoskeletal,neurological, endocrine, kidney, heart, lung, and liver manifestations, concomitant with other autoimmune diseases and malignancies[3]. Liver involvement in CD has been widely described in case reports and case series in the past fifty years. Presently, active screening for CD is recommended in patients with liver diseases, particularly in those with autoimmune disorders, fatty liver in the absence of metabolic syndrome, noncirrhotic intrahepatic portal hypertension, cryptogenic cirrhosis, and in the context of liver transplantation[4]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), estimated to affect approximately 25% of the world’s adult population, is the world’s leading cause of chronic liver disease[5]. Due to both diseases’ global significance, and to their correlation[6], this study aims to review the available literature on fatty liver and CD, and verify what has already been published on this subject in order to define the clinical particularities of their coexistence.

CELIAC DISEASE IN PATIENTS WITH FATTY LIVER

NAFLD refers to a spectrum of diseases of the liver ranging from simple steatosis (fatty infiltration of the liver) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (steatosis with inflammation and hepatocyte necrosis) to cirrhosis[7]. Massive hepatic steatosis complicating adult celiac has been described since the 1980s.These cases had a marked increase in aminotransferases, sometimes coursing with jaundice and transitory liver failure, presenting complete resolution of the liver condition after a gluten-free diet(GFD)[8-11]. A few authors have investigated the diagnosis of CD in patients with fatty liver by employing different screening methods (Table 1)[12-18]. The methodologies differ between the studies,both with regard to the diagnosis of fatty liver and the serological and histological diagnosis of CD. The prevalence of reactive celiac antibodies varies from 2% to 13%[12-16]. CD has been described as more prevalent in NAFLD patients with body mass index value < 27 kg/m2[16] and < 25 kg/m2[17].

Table 1 Celiac disease in patients with fatty liver

A clinical picture of undiagnosed chronic diarrhea, bloating, refractory anemia, dermatitis herpetiformis, suboptimal body mass index (< 24) or nutritional deficiency (vitamin B12, vitamin D or folic acid) in patients with NAFLD are associated with high likelihood of CD[18]. Liver biochemistry and celiac antibodies become normal after a GFD[12,14,16]. When either abdominal ultrasound or liver biopsy are performed after treatment, steatosis resolution is observed[12,16]. Concerning this topic,controversy persists as to whether the presence of fatty liver is a hepatic manifestation of CD[19]. Some claim that the hepatic manifestation of CD would be a nonspecific chronic hepatitis[13], called by some authors celiac hepatitis[20]. Furthermore, it is not known whether liver disease associated with CD has the potential to progress to liver cirrhosis, although it has been reported that CD is associated not only with cirrhosis of various etiologies, but also with cryptogenic cirrhosis[21-24]. The association between metabolic cirrhosis and refractory CD has also been reported[25].

FATTY LIVER IN PATIENTS WITH CELIAC DISEASE

Zaliet al[30] followed up on 98 patients with CD, and observed that 2% of the patients with CD fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome at diagnosis, while 29.5% of the patients met the criteria after 12 mo of GFD (P< 0.01; OR: 20). Agarwalet al[26] evaluated 44 naïve patients with CD, and observed that patients having fatty liver increased from 6 patients (14.3%) at baseline to 13 (29.5%) after one year of GFD (P= 0.002). Cicconeet al[27] evaluated the incidence of hepatic steatosis at diagnosis and during follow-up of 185 patients with CD. Hepatic steatosis was found by ultrasound in three patients (1.6%) at CD diagnosis. At the end of the follow-up period (median = 7 years; range 1–36), the prevalence of hepatic steatosis was significantly higher than at the time of CD diagnosis (n= 20; 11.0%) (P< 0.001). A Swedish nationwide study of over 26000 patients with CD demonstrated an increased risk of NAFLD in both children and adults with CD. The relative risk was highly increased in the first year of follow-up, but remained statistically significant even 15 years after CD diagnosis[28]. Tovoliet al[29]evaluated 202 celiac patients under a GFD and evidenced the diagnosis of NAFLD in 34.7% when compared with 21.8% in 333 controls. Curiously, in normal-weight patients the higher prevalence of NAFLD was even more evident than in the controls (20%vs5.8%,P= 0.001). On the other hand, this difference was not observed in the overweight population (67.8%vs55.4%,P= 0.202), suggesting that traditional metabolic risk factors may mask the effects of the GFD in these patients. Due to the above stated evidence, monitoring aminotransferases levels periodically in celiac patients under GFD isrecommended, especially in patients gaining weight[30].

Long-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) is associated with excessive weight gain[31,32]. Imperatoreet al[33] evaluated 301 patients with newly diagnosed CD, where 4.3% were diagnosed with metabolic syndrome and 25.9% presented with hepatic steatosis at the time of CD diagnosis; 32.8% had long-term exposure to PPI during the study period. After one year, 23.9% of the patients had developed metabolic syndrome and 37.2% had developed hepatic steatosis. Upon multivariate analysis,HOMA-IR (OR: 9.7;P= 0.001) and PPI exposure (OR: 9.2;P= 0.001) were the only factors associated with the occurrence of hepatic steatosis in celiac patients.

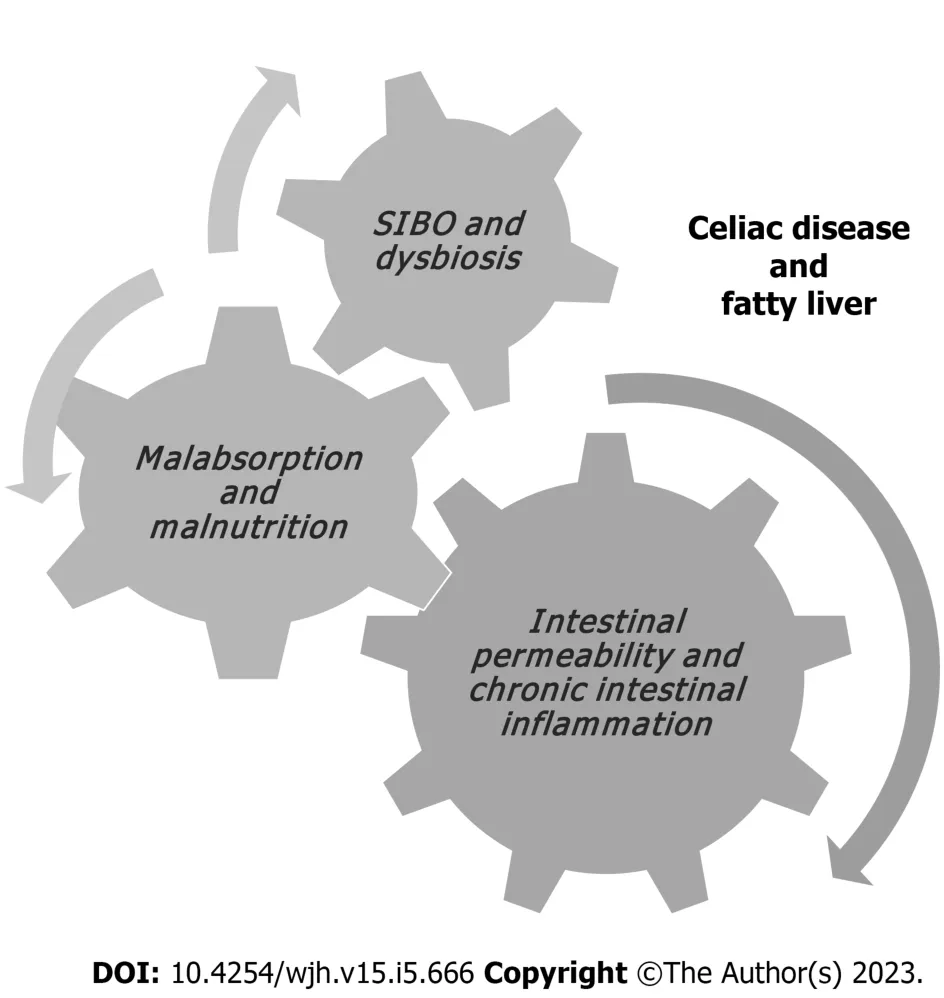

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS THAT LINK DISEASES

The mechanisms leading both CD and GFD to the metabolic alterations such as the increase in body weight and body mass index, blood triglyceride and cholesterol levels and blood glucose levels, as well as the development of NAFLD remain to be clarified[34]. In non-celiac patients, insulin resistance leads to fat accumulation resulting in steatosis and oxidative stress, determines lipid peroxidation and increases cytokine production, that results in inflammation and necrosis[35]. In celiac patients,malabsorption and long-standing malnutrition, increased intestinal permeability, chronic intestinal inflammation, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and/or dysbiosis have been suggested to have possible roles in establishing celiac hepatitis in CD (Figures 1 and 2)[36,37].

Malabsorption and long-standing malnutrition

At diagnosis, CD patients have lower body mass index than the general population due to malabsorption[38,39]. Kwashiorkor and dietary protein deficiency may occur associated with fatty liver on liver biopsy[40]. In patients with significantly reduced intestinal absortive surface, the ability to assimilate dietary protein may be severely reduced; intestinal malabsorption per se has been associated with hepatic steatosis after jejunoileal bypass in patients with morbid obesity[41,42] and also in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, specially after extensive intestinal resections[43]. It has been hypothesized that malabsorption in CD might lead to chronic deficiency of a lipotropic factor, and that fatty liver may occur with an associated pyridoxine deficiency[44]. In addition to malnutrition itself,qualitative and quantitative changes in the intestinal microflora occur in protein-energy malnutrition[45], however the subject of dysbiosis will be addressed below. Weight changes are common in patients suffering from CD after commencing a GFD[46,47], and the GFD dietary behavior of CD patients correlates with NAFLD[48]. A possible explanation would be the ingestion of gluten substitute products paired with the hyperphagic compensatory status that usually follows malabsorption inducing weight gain[29]. There is evidence that GFD can determine a higher intake of simple sugars, proteins and saturated fat and a lower intake of complex carbohydrates and fibers[49,50]. These changes can contribute to the development of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome and hepatic steatosis[51].

Figure 1 Pathophysiological mechanisms associated with fatty liver in patients with celiac disease.

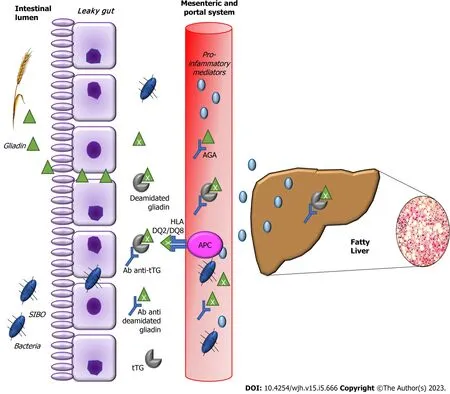

Intestinal permeability and chronic intestinal inflammation

Intestinal permeability is increased in CD[52] and may favor the absorption of antigens by the intestine,viathe portal circulation[53]. It is known that intestinal permeability is increased in NAFLD, as is bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine, and that these factors are associated with the severity of hepatic steatosis. The increase in intestinal permeability appears to be the key in the contribution of the gut-liver axis to the development of NAFLD[54]. The term gut–liver axis refers to a close anatomical,metabolic, and immunologic link between the gut and liver. The liver and intestine are tightly connectedviathe mesenteric and portal system, which supplies the liver not only with nutrients but also with gut derived food, bacterial antigens, and bacterial metabolic products. The liver portal circulation, derived from the mesenteric vessels, are the afferent part of the gut–liver axis[55]. Patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD present advanced intestinal inflammation and villous atrophy and higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines than those with CD alone, which suggests advanced intestinal injury when both diseases are present in one individual[18]. Moreover, the intestines and the liver are characterized by shared lymphocyte homing and recruitment pathways. Gut-derived T-lymphocytes may also contribute to hepato-biliary inflammation[56]. Additionally, patients with concomitant NAFLD and CD reveal higher levels of hepatic steatosis, liver stiffness, hepatic fibrosis progression rates and profibrotic mediators compared with those with either NAFLD or CD alone[18].

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and/or dysbiosis

The diagnostic standard for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is the detection of > 105colony forming units of bacteria per ml of jejunal fluid. The difficulty in collecting jejunal fluid has led to the development of new diagnostic methods, one of them being the hydrogen breath test[57]. Wigget al[58]observed that small intestinal bacterial overgrowth was present in 50% of patients with NAFLD and 22% of control subjects (P= 0.048), while intestinal permeability and serum endotoxin levels were similar in the two groups. For the CD patients, gliadin may impair the balance between intestinal microflora and the human body. Through digestive process, large quantity of undegraded gliadin reaches the intestines, delivers abundant substrates for different bacteria, contributes the reproduction of gliadin-degrading bacteria and breaks the steady state of intestinal microbiota[59]. Rubio-Tapiaet al[60] observed a prevalence of SIBO of 9.3% diagnosed by quantitative culture of intestinal aspirate in CD patients. The association between SIBO and CD occurs mainly in patients who are newly diagnosed and beginning a GFD, and specially in those with nonresponsive CD[61,62].

Figure 2 Molecular mechanisms that link fatty liver and celiac disease.

WHEN TO INVESTIGATE

Screening all patients with NAFLD for CD is controversial. Nonetheless, clinical suspicion may arise from the presence of classical malabsorption symptoms or low body mass index, leading to active screening of celiac antibodies and early diagnosis. The GFD may improve liver tests and liver steatosis in patients with NAFLD and CD, but it remains controversial whether this effect is independent of nutritional factors. Given the biological complexity and clinical heterogeneity of NAFLD and its comorbidities, the identification of the precise drivers of such disease would aid the development of targeted therapeutics[35]. International NAFLD guidelines[63,64] recommend the investigation of other diseases that may occur with liver steatosis and that have a treatment different from NAFLD, even in the presence of metabolic risk factors. From our point of view, CD represents a disease for which diagnosis requires targeted treatment to benefit the patient. This approach not only reduces the risk of developing more severe celiac-related liver injuries, but from a systemic point of view it is known that a GFD can prevent celiac complications such as intestinal malignancies and several autoimmune diseases.Screening for CD is justified in subjects with and without known risk factors for NAFLD. Priority groups include, individuals with chronic diarrhea, iron deficiency anaemia in absence of other causes,family history of CD, patients with autoimmune disease, Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves' disease,osteopenia or osteoporosis, recurrent aphthous ulcerations/dental enamel defects, infertility, recurrent miscarriage, late menarche, early menopause, chronic fatigue syndrome, acute or chronic pancreatitis after excluding other known causes and neurological symptoms such as unexplained ataxia or peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, headaches including migraines, mood disorders, or attention-deficit disorder/cognitive impairment[65]. On the other hand, it is not yet well defined whether it is necessary to investigate fatty liver in all patients with CD, as liver changes may be resolved with GFD. However, it is imperative to investigate fatty liver when liver biochemical tests persist elevated despite GFD.Figure 3 demonstrates an algorithm proposal for CD screening in patients with fatty liver and also for fatty liver screening among celiac patients.

Figure 3 Proposed screening algorithm for celiac disease in patients with fatty liver and vice versa.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

CD and NAFLD are a common association and prompt recognition of both diseases is crucial for adequacy of treatment and to improve care. Although a direct cause-effect relationship can be clearly observed in some patients with CD that develop NAFLD as a result of malabsorption; a subtler mechanism, in which CD acts more as a cofactor capable of changing the natural history of NAFLD, has recently been suggested. Therefore, screening for CD should be strongly considered in these patients,although there are no data that exactly define the priority groups. Future investigations focusing on the pathophysiological mechanisms, particularly on the role of changes in the microbiota and intestinal permeability, may help in understanding the interference of one disease on the other. In addition,longitudinal studies evaluating the progression of these patients, particularly the impact of the GFD on NAFLD outcomes, are essential to support the clinical decision-making process.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Narciso-Schiavon JL designed the research, collected clinical data, analyzed the data and wrote the paper; Schiavon LL designed the research and reviewed the paper; all authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Brazil

ORCID number:Janaina Luz Narciso-Schiavon 0000-0002-6228-4120; Leonardo Lucca Schiavon 0000-0003-4340-6820.

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies:Asociación Latinoamericana para El Estudio del Hígado;Federação Brasileira De Gastroenterologia; Sociedade Brasileira de Hepatologia; Associação Catarinense para o Estudo do Fígado.

S-Editor:Xing YX

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Xing YX

杂志排行

World Journal of Hepatology的其它文章

- Cerebrospinal fluid liver pseudocyst: A bizarre long-term complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt: A case report

- Giant cavernous hemangioma of the liver with satellite nodules:Aspects on tumour/tissue interface: A case report

- Liver steatosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate is associated with body mass index

- Respiratory muscle training with electronic devices in the postoperative period of hepatectomy: A randomized study

- Current guidelines for diagnosis and management of hepatic involvement in hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia

- Sarcopenia in chronic viral hepatitis: From concept to clinical relevance