Animating Tradition: The “Animated” Performance of Paper Puppets

2023-04-21LiBaochuan

Li Baochuan

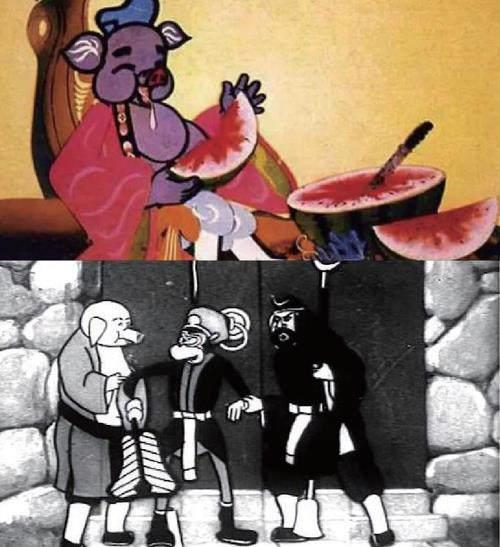

This book meticulously traces and explains the nearly 70-year development journey of paper-cut animation from its experimental beginnings in 1957 with Pigsy Eats Watermelon to the present. Through an examination of the historical origins, evolution, significant events, stylistic schools, and interpretation of works of paper-cut animation, readers are provided a visual history supported by firsthand historical materials. This helps readers understand the connection between paper-cut animation and the “Chinese Animation School,” while also showcasing the history of Chinese animation development.

When one mentions paper-cut films, the first that comes to mind is Pigsy Zhu Bajie Eats Watermelon. Mentioning Wan Guchan, industry peers think first of the pioneers of Chinese animated film, the brothers Wan Laiming and Wan Guchan. Wan Guchan was not just the founder of Chinese animated films but also the originator of paper-cut animation.

Wan Guchan, originally named Wan Jiaqi, and his twin brother Wan Laiming were born in 1900 in an old house in Heilang, Nanjing. As children, the Wan brothers were quite mischievous. To get them to sleep early, their mother would use the lamplight to cast shadows of various animals with her hands onto mosquito nets or walls, creating images of horses, chickens, cows, sheep, and scenarios like Rabbit Admiring the Moon and Old Farmer Returns Late. This impromptu “shadow play” piqued the brothers interests, planting the seed for “shadow drama” in their hearts. In their eyes, their mother was dexterous, excelling at embroidery and paper-cutting, a woman of many talents. Thus, she became their first artistic influence.

What truly caught the Wan brothers attention was shadow puppetry. During festivals, artisans from all over would gather by the Qinhuai River in Nanjing to perform or sell folk toys. They saw puppet shows, lanterns, and shadow puppet plays, all of which were new to them. “Especially the shadow puppetry, which used light to cast characters shadows. Characters danced and performed, floating on clouds, talking and singing, all with plotlines. This was much more sophisticated than mothers hand shadows.” (Narrated by Wan Laiming, written by Wan Guhun, (Me and the Monkey King, Beiyue Literature & Art Publishing House, October, 1986)

Since childhood, the Wan brothers had a strong desire to imitate and express themselves. When they encountered something they liked and found interesting, they would invariably try to emulate it, practice it, and refine it. This led the twins to master paper-cutting skills from an early age. Its said that by his teens, Wan Guchan could effortlessly cut out various animal and human figures without drafting. Brushes and scissors became the favorite toys of the young brothers Wan Laiming and Wan Guchan. Moreover, Wan Laimings exceptional paper-cutting skills, which accurately captured the essence of objects, earned him the reputation as the “Number One in Silhouette Cutting.”

The Wan brothers always fantasized about their paper “drawing” being able to “move.” While they sketched on paper, they also used scissors to create vivid figures. These two methods, although seemingly contrasting, seemed to converge through their extensive creative endeavors. The concept of natural “movement” necessitated the “drawing” to be separated from its background. This nascent understanding shares similarities with the principles behind popular traditional shadow puppetry and revolving lantern shows. To showcase this advanced technique, Wan Guchan and his siblings employed the basic principles of shadow puppetry. They crafted their own set of shadow play tools and even improvised performances like Borrowing Your Enemys Arrows, and Pigsy Takes a Wife. This intense passion for art during his younger years and his interests from childhood genuinely influenced Wan Gu Chans pursuit of art and laid the foundation for his future involvement and sentiment toward animated films.

The Inception of Paper-cut Animation Art

In an era where national cinema faced immense challenges, producing a local animated film was a formidable journey. In 1920, while Wan Guchan was attending Shanghai Art Colleges Western Art Department, American cartoons began to be shown in China. These “shadow plays” instantly reminded him of his childhood, igniting a strong desire to create. He thought that if the techniques of foreign animated films could be integrated with imagery that has a Chinese national style and meaningful content, and presented as educational films for our countrys children, it would greatly enrich the lives of the vast majority of children. After graduating from the art academy, Wan Guchan remained at the school as a Western art instructor due to his excellent performance. In his free time, he began to explore the secrets of making “cartoons” with his brothers.

Being a foreign import, animation technology was naturally monopolized by the West. Despite the lack of technical resources, trial funds, and production equipment, Wan Guchan and his brothers scrimped and saved to gather funds. After numerous failures, they finally brought their drawings to life and produced Chinas first cartoon advertisement, Shu Zhendong Chinese Typewriter, in 1925. Though this short film seemed rather basic, it marked a pivotal beginning for Chinese national animation.

From then on, animation became closely intertwined with the fate of the Wan brothers. Starting from the 1920s, the animations they developed progressed from silent to sound and from short to feature-length. They produced nearly 20 animations, including Chinas first sound film, The Camel Dances, and the first Chinese and fourth worldwide animated feature film, Princess Iron Fan. These efforts achieved significant success and accumulated a wealth of creative experience. However, this animation creation process, with its arduous beginnings and twists and turns, progressed in tandem with the turbulent changes happening in society at the time. Undoubtedly, the main factor restricting animation production was a lack of funding. In his passion for animation, Wan Guchan constantly sought more economical and simpler techniques to reduce high production costs. During this period, in addition to having to build their own photography equipment from scratch, they also utilized techniques combining live actors with animation in their creative productions. These approaches were unavoidable solutions given the constraints around manpower, materials, and funding they faced at that time.

According to Professor Wan Baiwu, Wan Guchans son, “After shooting Princess Iron Fan, my father felt that animation demanded high-quality artwork and the process of drawing frame by frame was too cumbersome and time-consuming. He often pondered if there could be a method to replace manual drawing and enhance efficiency. Between 1942 and 1945, he designed a small figurine and had a skilled mechanic make it according to his design. This device, resembling todays articulated dolls, was about 12 cm tall. The dolls joints consisted of steel balls sandwiched between two copper plates, with small iron rods welded between them to form hands, legs, and feet. The head was made similarly. The dolls hands, feet, and head were movable, and even the lips on its hollow paper head could be slightly adjusted. The dolls feet had three pointed pins for stability. Different heads and outfits could be attached to represent various characters, and adjusting the dolls limbs could produce different postures. However, this ingeniously designed device did not help my father realize his dream; it merely became a toy during my youth. But my fathers relentless dedication to animation finally bore fruit in his paper-cut animations.”

As a general rule in the evolution of artistic forms, no art form emerges out of the blue. It invariably undergoes an inception phase, a period of outstanding exploration, the maturity of necessary technical conditions, and finally culminates in the sublimation and innovation of its expressive forms. As a child, Wan Guchan was fond of paper-cut art and shadow puppetry. This primitive principle of “moving” art reignited his desire to create animations using paper puppets. It could be said that paper-cutting, a unique folk art form, continually influenced Wan Guchans work. His spontaneous childhood interest in “moving” art led to a conscious love for “animation.” He inadvertently linked paper-cutting with animation. Although the concept of creating paper-cut animations hadnt fully formed at this stage, the idea had already sprouted. He gave it much thought and made numerous attempts, but he hadnt yet settled on paper-cutting as the definitive style.

However, when it came to actual animation production, the challenges faced by the Wan brothers were endless. In the beginning, they didnt use cel material for drawing and relied solely on white paper. This meant drawing characters and backgrounds on the same sheet, which inevitably affected the workload and the resulting animation quality. Its worth noting that the Wan brothers did experiment with “paper-cut” animation during their early stages of animation technology development. Regarding the circumstances at that time, Wan Guchan wrote in the July 1948 (Volume 6, Issues 9 & 10) article Talking About the Current State of Domestic Animation Film Research in Cinema Audio Monthly magazine: “Around twenty years ago, when I applied this method, it resulted in a huge blunder. Back then I was working on an animated advertisement short film for the Commercial Press Typewriter division. To save effort from having to draw thousands of backgrounds, I tried to cut corners by asking Commercial Press to print several thousand backgrounds. I then drew the characters into the blank spaces on those printed backgrounds. This approach saved me from repeatedly drawing the same backgrounds, but it resulted in shaky lines between the characters and backgrounds”. Watching it was quite uncomfortable. Later, they changed to drawing a single background. The characters were drawn on separate sheets. During filming, areas around the characters were cut out to reveal the background placed beneath the character sheet. With the method described above, the positions of the backgrounds and character actions had to be predetermined.

Separating the characters from the background, allowing them to move freely, and arranging them in “layers” in terms of depth, was a significant technical advancement in early animation. Wan Guchan specifically mentioned this in his writings, especially the part about needing to “predetermine the positions of the backgrounds and character actions,” which closely resembles the later stop-motion animations “pose action.” The only difference was that during this period, the paper puppets were whole, without joints, so they couldnt move freely. (Note: After the advent of paper-cut animation, when characters in distant shots were too small to utilize articulated “pose action,” whole paper puppet designs were used. A series of such puppets would be used to break down a single motion, ultimately producing the final animated sequence through sequential shooting). Regardless, animation during this period didnt see much development. The Wan brothers use of paper puppets to test animation was merely a technical trial due to circumstances. It couldnt yet be considered paper-cut animation. However, the idea of creating paper-cut animation was already planted as a “seed” in the Wan brothers career. Only after they started using celluloid did animation undergo a revolutionary change, ushering in its long-term development.

Apart from animation, we can catch a glimpse of the shadow of “paper-cut animation” in Wan Guchans other early works. In the mid-1930s, as comics were flourishing as an independent art form, the Wan brothers not only created animations but also made meaningful explorations in comics. Wan Guchans serialized comic Smiling Monkey and Wan Laimings “Miss Lu” were artistic creations that not only broke away from imitating Western comics, forming their unique style but also became hot animation stars at the time. They stood on the same stage as Zhang Lepings Sanmao, Ye Qianyus Mr. Wang, and Huang Yaos Bull Nose, entering peoples lives. (Note: During this period, since their works were all signed as the “Wan Brothers,” academia mistakenly attributed Smiling Monkey to Wan Laiming.)

When admiring the Wan brothers comics, it feels like looking at the frames of an animation. Theres continuity between the panels, and even without any text, the humor and fun within can still be understood. For example, the comic The Unfortunate Life of a Beauty could be considered more as one of Wan Guchans earliest paper-cut animation works rather than just a comic.

History of Chinese Paper-cut Animation

Li Baochuan

Lingnan Fine Arts Publishing House

August 2022

98.00 (CNY)

Li Baochuan

Li Baochuan is the head of the Animation Department, associate professor, masters supervisor at the School of Culture, Creativity and Media at Hangzhou Normal University, an expert in animation history research, and an animation curator. He curated the 50th-anniversary exhibition of Havoc in Heaven, the Wan Laiming Exhibition, and the first and second Animation Festival in Hainans Southern Sea.