The Prosperity of Buddhist Art in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang

2023-04-21YangQi

Yang Qi

This book is an introductory course on Dunhuang art for the general public, penned by a Tsinghua University professor. It includes murals, silk paintings, colored sculptures, flying apsaras, music, dance, architecture, scriptures, and daily life. Spanning ten dynasties, featuring 250 exquisite images, this book recounts the millennia-long evolution of Dunhuang art. The artistry is narrated vividly, opening the doors to Dunhuang art for readers.

Naturally, Dunhuang has a deep-rooted cultural heritage, grown under the long influence of Confucian thought. No external cultural influx could completely alter this inherent cultural foundation. After the Northern Wei Dynasty, due to Emperor Xiaowens reforms, Buddhist art centered around the Longmen Grottoes spread to Dunhuang. Artists ingeniously fused Central Plains culture with Western Region influences, ushering in the golden age of Dunhuang cave art.

The Tang Dynasty was the zenith of Buddhist development. As the Tang Dynasty marked the pinnacle of feudal society in China, enriched by centuries of artistic heritage, it saw the height of the Mogao Caves artistry.

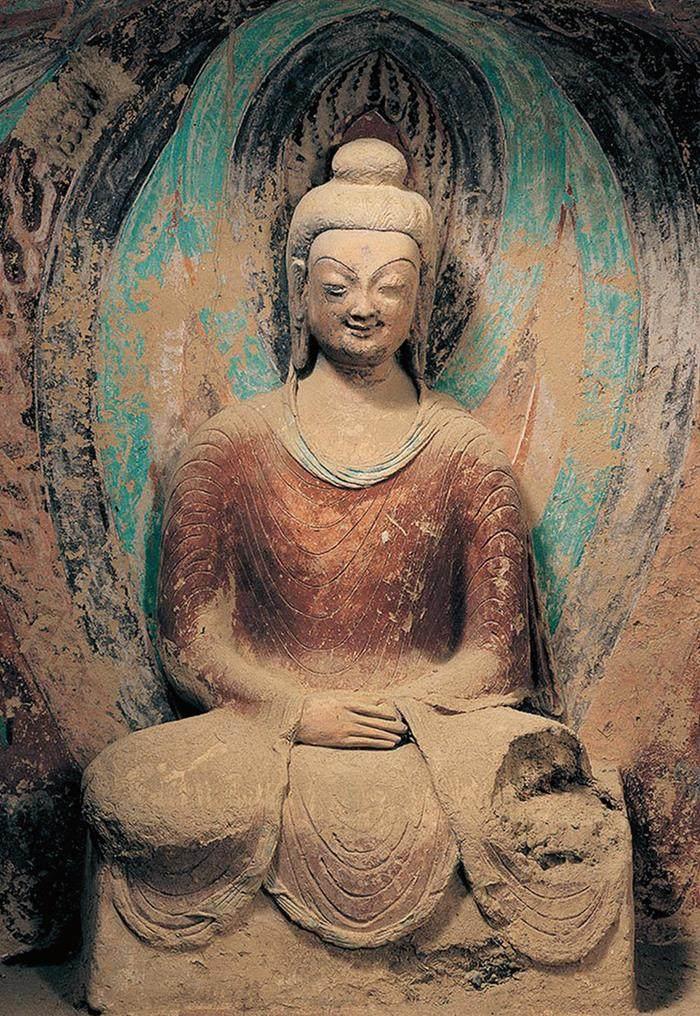

The hallmarks of the Tang Dynastys pinnacle in Mogaos art include: First, the creation of grand grottoes and majestic Buddha statues. Second, an art style characterized by its elegance and grandeur, manifested in full-bodied and rounded sculptures, delicately crafted eyebrows and eyes, lavish attire, and dignified expressions. Especially the colored Bodhisattva sculptures of the Tang Dynasty, which epitomize the art style of Mogaos heyday—high hair buns, pronounced chest muscles, slender waists, arching eyebrows, and gentle eyes capturing the elegance of Tang Dynasty nobility. Thirdly, by the Tang Dynasty, the portrayal of figures had fully embraced Chinese characteristics, individualism, and secularism.

The Dunhuang cave art of the Tang Dynasty, while rooted in the Central Plains art style, actively absorbed foreign artistic elements, culminating in a uniquely Chinese Dunhuang art style.

This Chinese-centric Dunhuang art style is marked by its shift from the divine to the secular.

Tang Dynasty sculptors, breaking away from strict Buddhist iconography, based their works on real-life Han Chinese subjects. They boldly incorporated courtesans, foreign merchants, noblewomen, warriors, emperors, ministers, monks, and nuns, artistically interpreting and exaggerating them into numerous Buddhist depictions in the Mogao Caves. While the individualism and secularism of the Buddhist figures in the Sui Dynasty caves were initial improvements from the Northern Dynasties, those in the Tang Dynasty caves were individualistic and secular, unparalleled in history.

The Bodhisattva depictions of the Tang era are fundamentally based on beautiful young women. These supposed Bodhisattva images are essentially secular young women cloaked in Buddhist imagery. Beneath the Buddhist exterior, the passions, hearts, dreams, appearances, and personalities of ordinary people pulse and breathe. Yet, within the Dunhuang caves, they are all idealized.

The artist Zhang Daqian, in the late spring of 1941, journeyed from Chengdu by plane, car, mule cart, and finally horseback to reach Dunhuang. The very evening he arrived, he eagerly entered the caves with a flashlight and candles. On the main wall, he saw a painted attendant standing gracefully, with full cheeks, clear brows, and beautiful eyes. The lines of her attire were soft yet powerful, bringing her to life. Zhang Daqian observed her repeatedly, marveling at her beauty, reluctant to leave.

Zhang Daqian remarked, “By the Tang Dynasty, portrait art had reached an unparalleled realm of perfection. Many female Bodhisattvas in the Dunhuang caves, though clearly murals, can still captivate ones heart.”

Secularism inevitably leads to individualism. Every individual in the secular world is unique. Originally, celestial maidens belonged to the distant Buddhist realms. Yet, the celestial maidens in Dunhuang murals of this era werent mere symbols devoid of secular emotions but were expressions of individual personalities. Look at those celestial maidens, each distinct, with no two alike, some stand, some sit, all graceful. Some listen intently to Buddhas teachings; Others whisper, their eyes darting playfully or dance joyfully, exuding boundless happiness, and just like the beautiful young women of the world, exuding a myriad of emotions with every gesture.

The colored sculptures in the Mogao caves, especially those in caves 45, 205, and 328, from the early to the height of the Tang period, are truly unparalleled.

The sculptures in Cave 328 are original Tang Dynasty works, possessing immense artistic value. The cave showcases one Buddha, two disciples, two Bodhisattvas, and four attendant Bodhisattvas. Besides the Buddha, seated Bodhisattvas are present. Additionally, there are Bodhisattvas in a kneeling foreign style—a new form that emerged in the Tang Dynasty.

Dunhuang Art:

A Comprehensive Course

Yang Qi

CITIC Press Group

July 2023

138.00 (CNY)

Yang Qi

Yang Qi is a senior professor from the Department of Art History at Tsinghua Universitys Academy of Fine Arts. Besides teaching, he has long been involved in popularizing art among the masses.